Posts Tagged ‘Institute for China’s Democratic Transition’

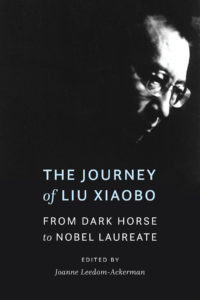

The Journey of Liu Xiaobo: From Dark Horse to Nobel Laureate

The Journey of Liu Xiaobo: From Dark Horse to Nobel Laureate, published April 1 by Potomac Books (The University of Nebraska Press) tracks the life and ideas of the scholar, poet and activist who has been called the Nelson Mandela of China. It has been my privilege to edit this volume, along with colleagues of Liu’s. Below is my editor’s note to introduce this book which I hope readers will embrace to celebrate Liu Xiaobo’s life and legacy. (Essay reprinted with permission of Potomac Books.)

“Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth.”—Liu Xiaobo, I Have No Enemies: My Final Statement

Available at Potomac Books, Politics and Prose, Barnes and Noble, Amazon, Powells, and Indiebound

Editor’s Note

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

A zoo in China placed a big hairy Tibetan mastiff in a cage and tried to pass if off as an African lion. But a boy and his mother heard the animal bark, not roar. As news spread, the zoo’s visitors grew angry. “The zoo is absolutely trying to cheat us. They are trying to disguise dogs as lions!” declared the mother.1

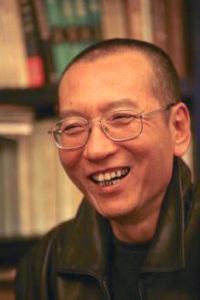

In 2009 the Chinese government put Liu Xiaobo, celebrated poet, essayist, critic, activist, and thinker into a cage, labeled him “enemy of the state,” charged him with “inciting subversion of state power,” and sentenced him to eleven years’ imprisonment. Liu Xiaobo was not an enemy, but he was a “lion” the state feared. He challenged orthodoxy and conventional thinking in literature, which he wrote and taught, and authoritarian politics, which he protested and tried to help reshape. His insistence on individual liberty in more than a thousand essays and eighteen books, his relentless pursuit of ideas, including as a drafter and organizer of Charter 08, which set out a democratic vision for China through nonviolent change, and finally his last statement, “I have no enemies and no hatred,” threatened the Chinese Communist Party and government in a way few other citizens had.

Dr. Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace, in 2010, but he was in prison, was not allowed to attend the ceremony, and died in custody in July 2017.

When news of Liu Xiaobo’s death reached the world and in particular the writers and democracy activists who knew him, writers began to write. Tributes and analyses poured in, many sent to the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), a gathering of writers inside and outside of Mainland China that Liu helped found and served as president. The Journey of Liu Xiaobo traces Liu’s history and the path of liberalism in China and is perhaps the largest gathering of Chinese democracy activists’ writing in one volume. Because of length restrictions, some tributes are listed only by authors’ names in the appendix.

A Chinese edition was published in 2017 as Collected Writings in Commemoration of Liu Xiaobo by Democratic China and the Institute for China’s Democratic Transition. It is hoped that this revised and expanded English edition, organized according to phases of Liu’s life and development, will find an even wider audience and offer insight into the person—his ideas, his loves, and his legacy. Some have suggested that because of Liu Xiaobo’s death and the economic and political ascendency of the current Chinese regime, Liu’s legacy has been reduced to a void. I would recommend that those who claim such consider the longer arc of history. The same was said of visionaries in Eastern Europe when earlier protests were crushed in Poland, East Germany, and elsewhere; the same was said of early martyrs in South Africa, where repression eventually led to widespread civic resistance and in other countries where civilians have challenged repressive systems. Liu Xiaobo was committed to nonviolent engagement and political change. Though he no longer walks the earth, his ideas and writings endure. History will unfold this story. In the meantime the essays in this volume recount one man’s journey and commitment to the struggle for the individual’s right to freedom.2

Societies move forward and are changed by ideas, by leaders, and ultimately by their citizens. None of these essays show Liu Xiaobo aspiring to personal power. But those in power worried about this man of ideas and this activist who set ideas into motion. He didn’t need to roar like a lion to garner the world’s attention and respect. By his life and his death he holds those in power to account.

Notes

———————————————————————————————————————

- Michael Bristow, “China ‘Dog-Lion’: Henan Zoo Mastiff Poses as Africa Cat,” BBC News, August 15, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-23714896..

- In these collected essays, a number of writers express concern about the fate of Liu Xiaobo’s beloved wife, poet and artist Liu Xia, who spent years under house arrest. Since the writing of these articles, Liu Xia has been allowed to go to Germany for medical treatment. As of 2019 she resides in Berlin.

Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo died this past July in prison, where he was serving an 11-year sentence for his role in drafting Charter ’08 calling for democratic reform in China. Below is my essay in The Memorial Collection for Dr. Liu Xiaobo, just published by the Institute for China’s Democratic Transition and Democratic China.

I never met Liu Xiaobo, but his words and life touch and inspire me. His ideas live beyond his physical body though I am among the many who wish he survived to help develop and lead democratic reform in China, a nation and people he was devoted to.

Liu’s Final Statement: I Have No Enemies delivered December 23, 2009 to the judge sentencing him stands beside important texts which inspire and help frame society as Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail did in my country. King addressed fellow clergymen and also his prosecutors, judges and the citizens of America in its struggle to realize a more perfect democracy.

I hesitate to project too much onto Liu Xiaobo, this man I never met, but as a writer and an activist through PEN on behalf of writers whose words set the powers of state against them, I can offer my own context and measurement.

Liu said June, 1989 was a turning point in his life as he returned to China to join the protests of the democracy movement. In June, 1989 I was President of PEN Center USA West. It was a tumultuous year in which the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was issued in February, and PEN, including our center, mobilized worldwide in protest.

In May, 1989 I was a delegate to the PEN Congress in Maastricht, Netherlands where PEN Center USA West presented to the Assembly of Delegates a resolution on behalf of imprisoned writers in China, including Wei Jingsheng, and called on the Chinese government to release them. The Chinese delegation, which represented the government’s perspective more than PEN’s, argued against the resolution. Poet Bei Dao, who was a guest of the Congress, stood and defended our resolution with Taipei PEN translating.

When the events of Tiananmen Square erupted a few weeks later, my first concern was whether Bei Dao was safe. It turns out he had not yet returned to China and never did. PEN Center USA West, along with PEN Centers around the world, began going through the names of Chinese writers taken into custody so we might intervene. I remember well reading through these names written in Chinese sent from PEN’s London headquarters and trying to sort them and get them translated. Liu Xiaobo, I am certain must have been among them, though I didn’t know him at the time.

In his Final Statement to the Court twenty years later, Liu told the consequence for him of being found guilty of “the crime of spreading and inciting counterrevolution” at the Tiananmen protest: “I found myself separate from my beloved lectern and no longer able to publish my writing or give public talks inside China. Merely for expressing different political views and for joining a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher lost his right to teach, a writer lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual could no longer speak openly. Whether we view this as my own fate or as the fate of a China after thirty years of ‘reform and opening,’ it is truly a sad fate.”

I finally did meet Wei Jingsheng after years of working on his case. He was released and came to the United States where we shared a meal together at the Old Ebbit Grill in Washington. I was hopeful I might someday also get to meet Liu Xiaobo, or if not meet him physically, at least get to hear more from him through his poetry and prose.

His words are now our only meeting place. His writing is robust and full of truth about the human spirit, individually and collectively as citizens form the body politic. I expect that both his poetry and the famed Charter 08, for which he was one of the primary drafters and which more than 2000 Chinese citizens endorsed, will resonate and grow in consequence.

Charter 08 set out a path to a more democratic China which I hope one day will be realized.

“The political reality, which is plain for anyone to see, is that China has many laws but no rule of law; it has a constitution but no constitutional government,” noted Charter 08. “The ruling elite continues to cling to its authoritarian power and fights off any move toward political change….

“Accordingly, and in a spirit of this duty as responsible and constructive citizens, we offer the following recommendations on national governance, citizens’ rights, and social development: a New Constitution…Separation of Powers…Legislative Democracy…an Independent Judiciary…Public Control of Public Servants…Guarantee of Human Rights…Election of Public Officials…Rural—Urban Equality…Freedom to Form Groups…Freedom to Assemble…Freedom of Expression…Freedom of Religion…Civic Education…Protection of Private Property…Financial and Tax Reform…Social Security…Protection of the Environment…a Federated Republic…Truth in Reconciliation.”

Charter 08 addresses the body politic. Liu Xiaobo’s Final Statement: I Have No Hatred addresses the individual, and for me resonates most profoundly. Its call doesn’t depend on others but on oneself for execution. He warned against hatred.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows). It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

At a recent conference a participant asked if Liu Xiaobo might have changed this statement if he understood how his life would end. A friend who knew him assured that he would not for he was committed to the idea. Liu Xiaobo’s commitment to No Enemies, No Hatred does not accede to the authoritarianism he opposed, but instead resists the negative. He aligns with benevolence and love as the power that nourishes the human spirit and ultimately allows it to flourish. Liu’s words and his ideas lived offer us all a beacon and a guide.