Posts Tagged ‘Tiananmen Square’

Hope: A Threshold of History

My wedding anniversary is June 3, but ever since the events at Tiananmen Square June 4, 1989, I merge the dates in my mind. I’m not sure why, but this year included, I made quiet dinner plans for our anniversary on June 4 by mistake. The Tiananmen memory for those who work on human rights does not recede. It isn’t visceral because I wasn’t there, but many of us watched first with hopeful attention the gathering of students and others in Beijing that spring and then in horror as the tanks rolled in.

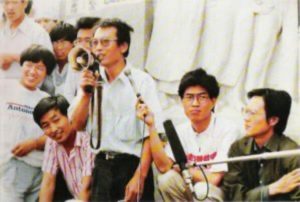

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Though the Tiananmen Square protests and the names of participants like Liu Xiaobo have been struck from the internet in China and not recorded in history books for mainland Chinese students, the courage of the demonstrators and the repression of the government remain as historical facts and as memory.

Unfortunately, the memory is amplified today like a solemn tolling bell, repeating a mournful sound in places like Belarus, Venezuela, Iran, and Myanmar, where citizens push against authoritarian forces with nonviolent resistance. That bell, however, also echoes a higher enduring strain of freedom sought and won over the decades by citizens in Eastern Europe, South Africa, Chile and other countries, citizens who ultimately prevailed.

Those outside the direct struggles can remember and can support those in the resistance. For many of my colleagues, the support is through the work of PEN which campaigns for writers on the front lines. Often it is writers who are early victims since they are articulating an alternate vision to the authoritarian regime and are reporting the facts. Others open space for those who must leave their countries or lose their freedom or their lives and must work from the outside, organizations like the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) which finds alternate locations for writers and artists.

In the last few months, I’ve taken this space of a monthly blog to return to posts from years past. I’ve taken a core sample as a slice of my history during that month. I do so again here and note several posts: June 2008: Back on the River, June 2009: A Time of Hopening and June 2017: Storm Cloud on a Summer’s Day. Hope is a fragile but essential tool, one that holds history together so that it doesn’t shatter on the shoals, on the disappointments and misbehaviors of humankind.

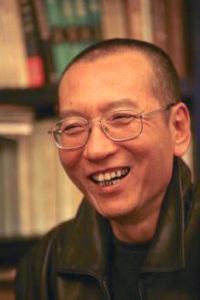

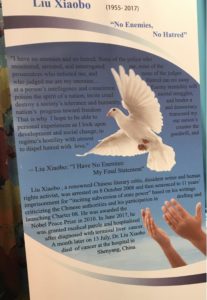

Liu Xiaobo was China’s first citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010, but he was in prison in China as “an enemy of the state.” Liu Xiaobo died in custody July 2017.

As I celebrate my wedding anniversary with my husband of many decades this June 3/4, I do so with the hope offered by Liu Xiaobo to his friends and fellow citizens whom he believed in when he noted in his “Final Statement:”

“I have no enemies and no hatred…Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience. Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress toward freedom and democracy…

“For there is no force that can put an end to the human quest for freedom, and China will in the end become a nation ruled by law, where human rights reign supreme…

“Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth. To strangle freedom of speech is to trample on human rights, stifle humanity, and suppress truth.”

Since April I’ve been back on the Potomac River, sculling in the rushing waters after the spring rains, dodging logs and flotsam flowing downstream from Great Falls and beyond. I’ve been pressing into the middle of the river on hot, sultry days in June when barely a breeze stirs the air, though the current still hurries beneath the boat. I’ve been rowing beside much larger sculls from the universities, dodging the wake of the speed boats which cruise along beside the Viking-size crafts as coaches shout instructions. In my small white scull I’ve tried to hear what they call and emulate the grace and power of the collegiate oarsmen and women.

Facing forward, watching the landscape recede as I move backwards, I’ve been thinking about the past even as I plunge into the future. This perspective of the rower, driving headlong towards what he can’t see except for quick glimpses over his shoulder, is a useful one to master.I’m back in Los Angeles this week for readings and interviews and will be talking about my own earlier fiction—No Marble Angels and The Dark Path to the River. Many of the short stories in No Marble Angels are set during the Civil Rights era—the Nashville sit-ins, the Little Rock school integration, the aftermath of the ’68 riots in the cities. It was a time when ordinary citizens took extraordinary actions. It’s easy to romanticize the times, but the consequence of many of those actions changed our laws and our lives and opened up our society. The future grew out of the clarity of purpose of those who could glance over their shoulders and press towards the future even as they had to face the restrictions of their present day.

As the U.S. moves into its next era—whatever that may eventually be called—one hopes it will be a period of national and international Rights Realized.

As a young mother, I used to tell stories to my two sons constantly—on the way to school, standing in long lines anywhere, on car, plane or bike rides, on hikes. I would ask each to give me two things (people, ideas, places, plots) they would like in the story, and then I would weave the disparate ingredients into a tale. Their elements might include something like a dog, a butterfly, a battle of some sort, and a waterfall…the possibilities were open and endless, though usually there was some battle involved and some animal in most of the stories.

Over the last year and a half, partly urged by my now adult sons, I’ve committed to writing a blog post once a month. For me the process is a bit similar to the earlier exercise as I look over the month and try to wrap ideas, thoughts, events into 600 words. This month’s elements are particularly rich, probably too rich for a 600-word essay, though the literary form of the blog hasn’t been established or defined so it can, I suppose, be whatever one wants.

I began June at an International PEN Writers in Prison conference joined to the Global Forum on Freedom of Expression conference in Oslo, Norway, where the sun doesn’t set in the summer. In Oslo, activists from organizations around the globe discussed, debated, and strategized into the summer nights about the state of freedom of expression around the world and the mechanisms to protect it. Everyone understood that societies without this freedom are most often without political and civil freedoms as well so the defense of freedom of expression is the front line.

The timing of the conference coincided with the 20th anniversary of the crackdown in Tiananmen Square in China. This year of 2009 is also the 20th anniversary of the popular uprising against the military government in Burma/Myanmar after the election of Aung San Sui Kyi, who was re-arrested this May; it is the 20th anniversary of the fatwa in Iran against Salman Rushdie after the publication of The Satanic Verses, and it is the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The year 1989 was a threshold year. So where have we come twenty years later?

After Oslo, I went briefly to Paris en route to Normandy, where the 65th anniversary of the World War II invasion was being celebrated. I was headed to Normandy for a bike trip through the countryside and the historical sites, not for the official celebrations, but I was in Paris the day President Obama and his family arrived. It was also the day of the men’s semi-finals of the French Open in tennis. (You see the elements of this blog complicating…)

Driving back to the hotel after Federer beat Del Potro and Soderling beat Gonzalez, I was talking in my broken French with the taxi driver talking in his broken English about the matches and about the arrival of Obama and about world politics in general. The driver was ebullient—an oxymoron perhaps for a French taxi driver—but he was ebullient nonetheless.

“The world…the U.S…France…Europe…it is hopening,” he said, gesturing with his arms, trying to explain what he meant about the opening he saw in the world and the hope he felt. “We have hopening between us!”…[cont]

June 2010: Summer Reading: Under a Tree With a Book

Summer has come with hot, steamy breath in Washington this year—already days nearing 100°. Even with the sudden flash of thunderstorms, the air clears only to steam up again. So much for my assurance to a newcomer that summer wasn’t so bad here, though maybe we will pay our dues in June and be rewarded with the summer breezes and cool evenings in July. August, we know, will be hot.

In the dog days it is a time to be indoors, or at least in the shade—biking along the Potomac or sculling on the river only early in the morning or as the sun is setting. Indoors or under the shade of a tree, it is a time to read.

Summer reading—the term brings back delicious childhood memories even of hot Texas summers where I would find a patch of shade in the back yard and lose myself in a book, or bike to a nearby pool and sit reading between laps, or curl up in a chair under the fan on the screened porch. I can still smell the mowed grass and the sweet fragrance of white gardenias on the bushes just outside.…[cont]

June 2011: Mockingbirds at Fort McHenry: A Tribute to Elliot Coleman

(The excerpt below is from a larger article about the poet and teacher Elliott Coleman in the recent Fortnightly Review:)

I was 20 years old, applying to Johns Hopkins graduate Writing Seminars from a small Midwestern college. I had come to campus to meet Elliott Coleman, the director and founder of the program. He had read my application and invited me to lunch at the Faculty Club. Looking back now and understanding the processes of application and the competition for a position in the Writing Seminars, I realize how remarkable his attention was, but he showed that kind of attention to students, making each feel important and valued.

I had sought out his work before I came to Baltimore. I no longer remember how I found the slim volumes of poetry in my remote college town before online ordering, but I did, and I had read his book of poems Mockingbirds at Fort McHenry. When I spoke about those poems, he was genuinely humbled and surprised that I had made the effort to read his books.

He asked, “Would you like to go see Fort McHenry?” That afternoon, the student showing me around drove us all out to Fort McHenry, and I walked around the area with Elliott Coleman as he talked about poetry and the genesis of his poems. I’m sorry I didn’t write down what he said, or if I did, I can no longer find the notes of that afternoon. But I knew then that Hopkins was where I wanted to be if I had the chance, and even though I was a fiction writer, I wanted to study with Elliott Coleman. Fortunately, I got that opportunity.

Elliott Coleman radiated a gentleness, a caring and a humility that shed light, illumining those around him. He didn’t seek the center of attention; he didn’t draw the spotlight to himself, rather he shined so that light fell on others.

From Mockingbirds at Fort McHenry:

Through a window in Tunis the green searolls its light. A few square white houses dazzle the Atlas mountains, the color of lions and honey. This foothill is hardly Africa; this bay is hardly Mediterranean. They partake of each other by reflection, absorbed as they are in the depths of space.

I recently engaged with facebook (no, I didn’t buy stock), but I gave in. I concluded that I needed at least to understand (is that possible?) and experience the social media phenomena and at most learn from and enjoy the connection to friends and colleagues, most of whom I know, but some of whom I just read and some of whom read me.

For the last three months I’ve checked my “wall” every few days and scroll through hundreds of shared observations, photos, and comments. The process is surprisingly quick. I engage more like a magazine editor with an unexamined metric for judgment, pausing to “like” certain contributions, commenting on a few and sharing even fewer on my own personal and authors’ facebook pages.

For the present at least I’ve limited my fb world and page largely to literature and human rights in order to put some boundary on the possibilities and on that evaporating commodity of privacy–not a 21st century value and an oxymoron in a discussion of facebook. That is not to say I don’t enjoy the news and photos and commentary on a range of issues from all the friends, but in my fb space, this is my focus for now.…[cont]

June 2013: No blog posted

June 2014: No blog posted

June, 2015: What Are You Not Reading This Summer?

I was recently sent a questionnaire as part of a profile asking me what I was reading:

I find myself reading several books at the same time. I just finished Phil Klay’s Redeployment today, am reading Jennifer Clement’s Prayers for the Stolen, am re-reading Graham Greene’s The Comedians, re-reading Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this and can’t leave this question without noting Elliot Ackerman’s Green On Blue. Because I read both e-books and paper books, I move around among narratives easily.

The answer was a snapshot in reading time, indicative of the pleasure of dancing among narratives. I find myself enjoying on several platforms the movement  between hard-edged, nuanced stories of war and its aftereffects in Klay’s Redeployment and Ackerman’s Green on Blue, the harsh and surprising world of Clement’s indigenous Mexican women in Prayers for the Stolen and the gentle, but no less desperate stories of Southern women trying to find their lives in Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this, a collection recently re-published by a new small press—Bacon Press—in paperback. Graham Greene is a master who I am always re-reading, appreciating how he integrates the international world of politics and deceit with compelling narratives set around the world.

between hard-edged, nuanced stories of war and its aftereffects in Klay’s Redeployment and Ackerman’s Green on Blue, the harsh and surprising world of Clement’s indigenous Mexican women in Prayers for the Stolen and the gentle, but no less desperate stories of Southern women trying to find their lives in Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this, a collection recently re-published by a new small press—Bacon Press—in paperback. Graham Greene is a master who I am always re-reading, appreciating how he integrates the international world of politics and deceit with compelling narratives set around the world.

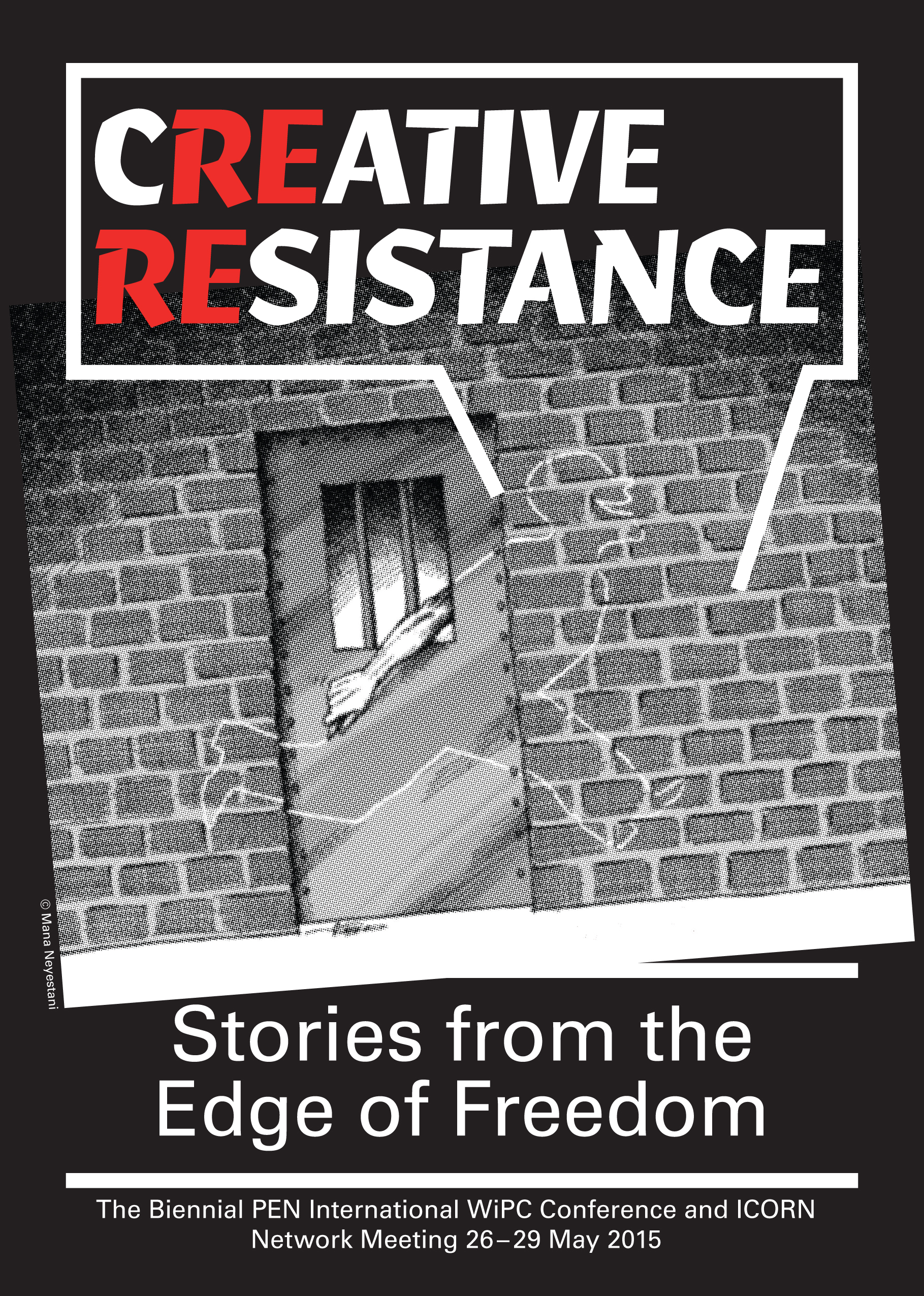

Recently I returned from PEN International’s biennial Writers in Prison conference and the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) meeting, a gathering this year in Amsterdam focused on Creative Resistance, a gathering of over 250 individuals from 60 countries around the world who work on behalf of writers threatened, imprisoned and killed for their writing. I remain conscious of these voices too. They occupy a kind of negative space—those we are NOT reading, not able to read because they are not able to write.

The list unfortunately is long, and many individuals stand out for me, but I will highlight two here. Though I couldn’t read either because of language differences, I read with attention their cases and link here to actions that can be taken on their behalf:…[cont]

June 2016: No blog posted.

June 2017: Storm Cloud on a Summer’s Day

It is an almost perfect summer day—the sun is shining in a white cloud sky; the air is warm, not yet sweltering. Light filters through white umbrellas shading diners at the outside restaurant by the park. On this almost perfect New York day I am thinking about the rulers in China who have imprisoned for the last nine years one of the country’s courageous thinkers for ideas that will outlast him and his jailers.

Today it was announced Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo is in critical condition, on medical parole having been given a terminal diagnosis. As a principal author of Charter’08 which advocates for nonviolent democratic reform in China, Liu Xiaobo, writer, critic and activist has lived his life as a man of ideas.

As the sun shifts above me, skirting over skyscrapers, finding a gap between the umbrellas and spreading over my table, I consider the trajectory and the life of an idea as it dawns, unfolds, iterates, then flies off where it is embraced, where it empowers and takes on a life of its own. Ideas are connected to, but not owned or encumbered by, those who articulate them.

The fallacy—the fundamental fallacy—of the rulers in China and elsewhere lies here. No one can imprison ideas. No one can manage or own the imagination of another. Government leaders can physically restrain with the hope that the idea will die, but in the case of Liu Xiaobo, the ideas behind Charter ’08, which was signed by more than 2000 Chinese citizens from all walks of life, endure. These ideas calling for a freer society continue to grow wings, often quietly, but sometimes even more quickly as the physical confines grow harsh.

“Any man or institution that tries to rob me of my dignity will lose,” declared Nelson Mandela. It is an injunction worth noting.

June 2018: No blog posted.

June 2019: [Beginning in May, 2019 I started writing a retrospective of work with PEN International for its Centenary so posts were more frequent in 2019-2020. In June 2019 there are two posts in the PEN Journeys and in June 2020 there are four.]

June 2019: PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.…[cont]

June 2019: PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move: East to West

I have attended 32 International PEN Congresses as president of a PEN Center, often as a delegate, as Chair of the International Writers in Prison Committee, as International Secretary and now as Vice President. The number surprises me when I count. The Congresses have been held on every continent except Antarctica. Many were grand affairs where heads of State such as Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia, Angela Merkel in Germany, Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal greeted PEN members. Some were modest as the improvised Congress in London in 2001 when PEN had to postpone the Congress planned in Macedonia because of war in the Balkans. PEN held its Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia the following year. At these Congresses writers from PEN centers all over the globe attended. Today PEN International has centers in over 100 countries.

Among the more memorable and grand was the 54th PEN Congress in Canada, held in September 1989 when PEN still held two Congresses a year. The Canadian Congress, staged in both Toronto and Montreal by the two Canadian PEN centers, moved delegates and participants between cities on a train. The theme—The Writer: Freedom and Power—signaled hope at a time when freedom was expanding in the world with writers wielding the megaphone.…[cont]

54th PEN Congress in Canada, 1989. Front row: WiPC chair Thomas von Vegesack, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman and PEN USA West Executive Director Richard Bray. Back row: Digby Diehl (right) and other delegates.

June 2020: PEN Journey 30: Barcelona: A Surprise

I was having lunch with my husband at a Georgetown restaurant in Washington, DC on a Saturday in May, 2004. I was due to fly out the next day for Barcelona to attend International PEN Writers in Prison Committee’s 5th biennial conference, part of a larger Cultural Forum Barcelona 2004. My husband and I were talking about our sons—the oldest was getting a PhD in mathematics and was also training for the 2004 Olympics as a wrestler, hoping to make the British team. (He had dual citizenship.) The younger, recently graduated with an advanced degree in International Relations, had just deployed to Iraq as a Marine 2nd Lieutenant and was heading into a region where the war was over but the insurgency had begun. It was an intense time for our family, yet as parents there was not much we could do except to be there, cheering for our oldest at his competitions and writing letters and sending packages and prayers for our youngest. It was a time when as parents we realized our children had grown beyond us and were taking the world on their own terms.

I was planning to be away for the week in Barcelona where PEN members from around the world were gathering for the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) and Exile Network meetings. Carles Torner, PEN International board member, chair of PEN’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and former President of Catalan PEN, had helped arrange International PEN’s participation and funding as part of the Universal Forum of Cultures—Barcelona 2004. This would be the largest WiPC conference to date with delegates from every continent and multiple speakers and side events.

Carles, a poet, fluent in PEN’s three official languages English, French and Spanish, was one of the highly respected, organized and talented PEN members. He’d also been involved in the years’ long reformation of PEN International. As members looked to who could be a strong replacement for the current International Secretary when Terry Carlbom’s term ended in a few months, there was widespread enthusiasm for Carles to stand for the office. I was among the enthusiasts.

My phone rang at that Saturday lunch. International PEN Board member Eric Lax, already in Barcelona for meetings, said he had news and a question; he told me he was calling on behalf of others as well. The news: the Catalan government had also recognized Carles’ talents and had offered him a position as Director of Literature and Humanities Division at Institut Ramon Llull to promote Catalan literature abroad. A father of three, Carles had accepted this paid position which meant he couldn’t stand for PEN International Secretary, an unpaid position. He wouldn’t have the time for both, and there would be conflicts of interest.

Eric asked if I would allow myself to be nominated. A number of members and centers, including the two American centers, were asking, he said. PEN’s Congress where the election would take place was only a few months away in September and nominations were due soon. I was flattered but said no for a number of reasons. Eric asked that I not answer yet, just come to Barcelona, talk with people and let them talk with me.…[cont]

June 2020: PEN Journey 31: Tromsø, Norway: Northern Lights

The week before PEN’s 70th World Congress in Tromsø, Norway in the Arctic Circle, my oldest son competed in the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, the only wrestler to qualify for TeamGB (Great Britain). He had dual citizenship and was the first British champion to qualify for the Olympics in wrestling in eight years. In his sport, there was no seeding of competitors; instead, after making weight, each wrestler reached into the equivalence of a hat and drew their first round competitions. True to his history, my son drew the best opponents. As one news commentator noted: “Coming to the mat is Nate Ackerman, born in the US, wrestling for Great Britain, getting his PhD in mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology…but that won’t help him now as he faces the three-time World Champion from Armenia.” My son lost to the Armenian wrestler. His other opponent was the world bronze medalist from Kazakhstan who went on to win the silver medal at the Olympics. Though my son didn’t win either match, he also didn’t get pinned, and he wrestled nobly. The Olympic Games in Athens was a magical time.

Olympic circles projected in light on the Acropolis at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens

I was heading to Tromsø with a smile inside, though behind my smile was also a quiet attention that never left me for my youngest son, a Marine, was in Anbar Province, Iraq that summer, patrolling in 120° and alert for IED’s and snipers along the roadside. He had missed his brother in the Olympics and his brother missed being able to talk with him.

As I changed planes in northern Europe, I realized I was going to need a coat in the Arctic Circle and bought a light foldable one at an airport shop which I took to a decade worth of PEN Congresses after. On the plane I reviewed the stack of PEN papers and resolutions.

I was arriving at the Congress having agreed to stand for International Secretary. (See PEN Journey 30). The other PEN member standing was Giorgio Silfer, a poet and playwright and president of Esperanto PEN.

Norwegian PEN hosted over 300 writers, editors, and translators from at least 60 countries for the 70thWorld Congress whose theme was Writers in Exile—Writers in Minority Languages. The Rica Arctic Hotel where we stayed and met was an easy walk to the small downtown of Tromsø, capital of northern Norway, well above the Arctic Circle and called “the Paris of the North.”…[cont]

June 2020: PEN Journey 32: London Headquarters: Coming to Grips

PEN is a work in progress. It has always been a work in progress during its 100 years. Governing an organization with centers and members spread across the globe in over 100 countries can be like changing clothes, writing a novel and balancing a complex checkbook all while hang gliding. Perhaps an exaggeration, but not by much.

In 2004 the leadership of President and International Secretary were at the center of the governing structure along with the Treasurer and a relatively new Board. The President represented PEN in international forums. The International Secretary was tasked with overseeing the office and the centers of PEN and with any tasks the President handed over like running board meetings and setting up the agenda for work. The concept was that PEN should be able to elect as President a writer of international stature to represent PEN in global forums but not have the obligation to run the organization. That could be the role of the International Secretary, along with the Board and staff.

When I assumed the role of International Secretary, PEN did not yet have an executive director, though the consensus had built from the strategic planning process that we needed one. Both the President and International Secretary were volunteer, unpaid positions, which meant they were not full time. At the post-Congress board meeting after Tromsø, we agreed to begin a search for an executive director.

International PEN President Jiří Gruša

I suggested monthly board meetings, which had not been the practice. We could do these by phone, which meant there were only a few hours a day when everyone would be awake. If Judith Rodriguez in Melbourne, Australia could stay up past 11pm and Eric Lax in Los Angeles didn’t mind waking up at 7am, the rest of us—Takeaki Hori in Japan, Sibila Petlevski in Croatia, Eugene Schoulgin in Norway, Elisabeth Nordgren in Finland, Cecilia Balcazar in Colombia as well as President Jiří Gruša when he joined from Vienna or Prague and me in Washington, DC or London—could find our time zone and call in. The technology was not as sophisticated as today, and we didn’t yet use skype so the calls were not cheap, but we began to manage each month.…[cont]

June 2020: PEN Journey 33: Senegal and Jamaica: PEN’s Reach to Old and New Centers

A few days before I flew out to Dakar, Senegal for a PEN conference in November 2004, my youngest son, a Marine in Iraq, called and told my husband and me that we would not hear from him for a while. We knew, without being told, that the U.S. and British troops were likely about to return to Fallujah, the center of the insurgency. Civilians there had been advised to get out of the city, and they were leaving.

On the opening day of the PEN conference in Dakar, November 7, 2004, the battle for Fallujah began. The headlines in the newspapers in Dakar were about the civil war raging in neighboring Ivory Coast so I was not reading about Iraq during the five-day PEN Africa meeting. In 2004 there were no iPhones or phone news feeds and rare coverage of the Middle East was on the evening news. I was quietly attentive each day and prayerful and focused on PEN’s work.

I have modest notes from the first PAN Africa conference, but I have some of my most vivid memories, most particularly of the people I met and of my first trip to Gorée Island just off the Senegalese coast opposite Dakar, a place of its own historic upheaval. Gorée Island was the site of the largest slave-trading center on the African coast from the 15th to the 19th century, ruled successively by the Portuguese, Dutch, English and French. The dungeons and portals to the sea where men and women and children were sent out in chains still stood along with the stucco houses of former slave traders.

Gorée Island, site of slave trading in 15-19th centuries, off coast of Dakar, Senegal

A tall Gambian doctoral student assisting Senegalese PEN guided a few of us around Gorée. Fluent in French, English and Spanish, he was writing a doctoral thesis on the secrets of history and myth in the epic of Kaabu according to Mandingo oral traditions—clearly a future PEN member. Thoughtful, knowledgeable, he spent the day sharing history. During and after the Dakar meetings, our paths crossed in subsequent PEN conferences and congresses, and we know each other still. Dr. Mamadou Tangara earned his doctorate at the University of Limoges in France shortly after and eventually became the Gambian Permanent Representative to the United Nations. During Gambia’s constitutional crisis in 2016-17, he and other diplomats called for the president to step down peacefully; he was dismissed, but when power changed hands a few months later, he was reappointed as Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Gambia. The friendship with Mamadou Tangara remains and is one of my many valued friendships from PEN.

Mamadou Tangara (Gambia) and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary) on Gorée Island at PEN’s 2004 Dakar conference

Mamadou’s mentor at the time was an older Gambian journalist and editor Deyda Hydara, who joined PEN members from more than a dozen African centers in this conference to prepare for PEN’s first PAN African World Congress in Senegal in 2007. The Congress would be PEN’s first in Africa since the 1967 Congress in the Ivory Coast when American playwright Arthur Miller was International PEN President. Though the Gambia didn’t yet have a PEN Center, Deyda was planning on starting one. At the time Deyda Hydara was co-founder and primary editor of The Point, a major independent Gambian newspaper. He was also correspondent for AFP News Agency and Reporters Without Borders and was an advocate for press freedom and a critic of his government’s hostility to the media.

A month after PEN’s Dakar conference, the Gambian government passed a bill allowing prison terms for defamation and another bill requiring newspaper owners to purchase expensive operating licenses and register their homes as security. Deyda Hydara announced his intent to challenge these laws. Two days later on December 16, 2004 Deyda Hydara was assassinated on his way home from work. To this day his murder remains unsolved. The following year Deyda Hydara won PEN America’s Freedom to Write Award posthumously and later the Hero of African Journalism Award of the African Editors Forum.…[cont]

Around the World in Thirteen Years…

Slowly we are emerging from the pandemic year(s) though we are all still mostly in digital mode. Colleagues at home and abroad are squares on a screen with various backgrounds—real and virtual bookcases and vegetations, some, as I myself, often simply snapshots at our best. Unless you need to present, it is often easier to turn off the video camera and listen and participate in a meeting without worrying about sitting up straight.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

My screen shot is a reminder of times past as I’m standing by a wall above the Atlantic Ocean at Cape Finisterre, Spain, wind blowing my hair, wearing dark glasses, my pad of paper and pen at hand. Finisterre was where the ancients thought the world ended as they looked westward over the vast Atlantic Ocean.

But that is another story, one from a time when I thought the world’s connections were a given, not relegated to cyber.

For this monthly blog post, I’ve taken a core-sample of posts written in May since the blog began in 2008. If you’re interested, you can click the title and read the full post. The journey is through time and geography, ranging from Hong Kong to London to Krakow to Tunis to Tehran to Istanbul to San Miguel de Allende and Mexico City, to Bellagio and in the U.S. to Chicago and Washington, DC. With the exception of the post focused on a prisoner in Iran, I was in each city working, at conferences or researching or otherwise engaged in the places over the last 13 years. It seems a bit of a lifetime ago when the world was so easily transited.

May 2008: China from the 22nd Floor

On June 4 China will face the 19th anniversary of the killing of citizens occupying Tiananmen Square. Nineteen years ago as president of PEN USA, I remember well sorting through dozens of unfamiliar Chinese names as we sought to untangle what writers had been arrested. Today there are at least 42 writers imprisoned in China.

I wake up 22 stories in the air. Most of Hong Kong is in the air with thousands of high rises shooting into the sky. I’m in a cubicle—two small beds pressed against each wall, a tiny shelf between, a TV mounted on the wall at the foot of one bed. At the head of the bed is a large window so the room is airy and looks out on other windows in the sky.

I wake in the middle of the night because of jet lag and then again early in the morning before the sun rises. I turn on the TV whose screen flashes the financial news of Hong Kong—the major world indices, Hong Kong currency exchange rates, global gold prices, Hong Kong stock market prices, statistics on which the financial world relies, accompanied by jazz and elevator music. The only news channel on this hotel TV is the Chinese Broadcasting Company from the mainland; it broadcasts the mainland government’s view of the news…[cont]

May 2009: The Talking City–A Birthday Tribute (or) Tiananmen Square and the Fourth of July

I live in a political town, probably the most political city in the US. Debate and policy forums run all day and all night. Any day of the week you can find and attend debates on what should be done about North Korea, Iraq, Afghanistan, the Middle East, China, the economy in general—interest rates, taxes, trade and monetary policy; the economy in specific–the automobile industry, the oil industry; U.S. domestic policy in general—state vs. federal; US domestic policy in specific–abortion, health care, gay marriage, public education.

Washington likes to talk. Everyone has an opinion about almost everything, and you can hear those opinions formally at the think tanks and forums around town, on the cable news and talk shows, or in the restaurants and cafes. In the evenings at the receptions, the book parties, the embassy parties, the talking continues.

At the center of all the debate and discussion are the legislators, the executives and the President who will make the decisions after the talking is done, or more often while it is still going on…

I originally set out to write a blog about the upcoming 20th anniversary of the student protest and subsequent massacre in Tiananmen Square in Beijing on June 4; however, having taken this detour into Washington, I will stay there and appreciate the ability to talk and talk and talk and debate. Even though the plethora of opinions can wear one down after a while, it is possible to turn off the TV, decline the forum invitations, take a discussion of a novel to the receptions and remain watchful and grateful that there are so many opinions, so many involved citizens and officials and so many diverse policies to choose from…[cont]

May 2010: Introducing Isabel Allende

PEN Faulkner: Discovering Stories That Need to Be Told

From my introduction of Isabel Allende at the Washington National Cathedral

Isabel Allende has been called “a literary legend,” a “cultural bridge builder” and one of the most influential Latin American women leaders, but she is also like a good friend with whom you take off your shoes, curl up on the sofa and figure out life together.

I first met Isabel Allende over 20 years ago in Los Angeles when she was giving a reading. I was involved with PEN, who may have been co-sponsoring the program—I no longer remember—but I remember attending a powerful evening with my colleagues. For the past months I’ve been absorbed in continuing my reading of Isabel Allende, and I can confirm that I am one of her good friends—though she may not know this. But as a reader, I have the feeling I am not alone in this club, or tribe, because if you immerse yourself in her fiction and memoirs, you not only feel you know her from her easy and confidential prose, but you think she surely knows you because of her insights into life. And even if she doesn’t, you feel she might want to know you and then let you move into the tribe of people she collects around her…[cont]

May 2011: Memorial Day—Rolling Thunder and Beyond

When I began this blog, I promised…who? myself mostly, a few friends, family that I would post once a month. Most of the months I’m burrowing away on fiction, on the long process of writing a novel—writing, rewriting, thinking, rethinking. It is a different discipline to pull away from that marathon of 400+ pages and sprint to the end of the block with 4-600 words that have some cohesion and at least one idea worth passing on. I tend to put off this arbitrary deadline till the very end of the month.

So…this is a rather long throat-clearing on Memorial Day, a hot, steamy day in Washington, a day with the sun full and unobstructed in a clear blue sky. I’ve finished my fiction writing and now have the remainder of the afternoon to write May’s blog post. This space often focuses on issues abroad, but today I’d like to focus on Memorial Day, a time in Washington when Rolling Thunder motorcycle bikers roar through the streets to memorialize Vietnam and all vets and where flags fly at half mast to honor those who have died in wars.

Memorial Day was perhaps first celebrated in the U.S. in 1865, right after the American Civil War by freed African slaves in South Carolina at the grave site of Union soldiers. The African Americans honored the Union soldiers who fought to help win their freedom. Originally called “Decoration Day,” the event was declared a national observance in 1868 with a date specifically set that was not the anniversary of a battle. Both North and South had lost hundreds of thousands of men in the Civil War, but by the end of the next decade the national memorial observances honored those from both the Blue and Gray states.

The honoring of veterans who have given their lives in war through the centuries is an occasion, solemn and celebratory with speeches, politics, picnics and some reflection. As the U.S. begins pulling out of war zones, it is also a time to consider what journey we have been on—where it is yet going, where it has taken us and where it has taken others outside our borders. War cannot be completely bound by borders nor by time frames for war impacts history and the future of us all….[cont]

May 2012: History, Hope and Politics: London Before the Olympics

I’m back at Sticky Fingers restaurant in London on a gray, drizzling Sunday afternoon, visiting this site of our family’s youth, sitting in a red leather booth with a dark wood table, wooden blinds over the windows, rock and roll rhythms from the sound system, and Rolling Stones memorabilia covering every inch of wall space. This spot is down the road from where we lived in London in the 1990’s and where I used to sit writing most afternoons before my children joined me on their way home from school. I return here almost every time I visit London.

Today the booths are filled with other parents and children chattering and eating hamburgers and fries and salads on this bank holiday weekend. The management has changed; they no longer know me, but they are still accommodating, letting me sit in a booth with good light, working as long as I like.

Outside Sticky Fingers, London is preparing for this summer’s Olympic Games with new construction dotting the landscape. One of my other favorite restaurants I went to visit has been demolished and is now a construction site for a new hotel, with men working frantically in the hope of opening by July. In the City of London itself a hotly contested election has just concluded for the Mayor who will preside over the Olympic Games with the incumbent conservative winning, barely.

Across the Channel today, the French are voting on who will govern France, though the Olympics have no influence there. After all France lost the Olympic bid as any Brit will remind you. The political tuning fork of Europe is vibrating this spring between the conservative and socialist paths of governance. (By Sunday evening it was clear the Socialists and anti-austerity electorate had won in France and in Greece though it wasn’t clear how the economic realities would square with the political will or how the European monetary Union might calibrate.)

In the theaters of London which tourists come to see, a third of the dramas focus on World War I or World War II as the historic reference point when the nations of Europe broke into conflict.

However, in the present, London is concentrating on the summer games as it anticipates the world’s nations and athletes gathering, independent of political and economic differences. For two weeks in late July and August London will showcase competition in its most elegant, accomplished and constructive form in the XXX Olympic Games. What happens after that…well, that will be another story….[cont]

May 2013: Living In and Beyond History

The white horse-drawn carriages clomp on the gray stones of Old Town Krakow, circling this largest of medieval town squares in Europe. On the fringe sit restaurants with white and yellow umbrellas advertising Polish beers where residents and tourists dine on red-checked table cloths. In the center the Town Hall Tower dominates, and around the periphery old terraced houses and shops form an arcade where one can buy everything from pastries to books to clothes to shoes.

Today tourists can look out over the city from the observation deck at the top of the gothic Town Hall Tower, originally built of stone and brick at the end of the 13th century. The tower used to house the city prison with a medieval torture chamber in its cellars. Thirty miles to the west lay some of the worst torture chambers of the 20th century: the prison camps of Auschwitz and Birkenau, where an estimated three million people died during World War II.

This historic city of Krakow was the scene last week of “Writing Freedom”—the biennial gathering of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committees from around the world in joint symposiums with ICORN (the International Cities of Refuge Network) and the third Czeslaw Milosz Literary Festival.

Along the Vistula River writers gathered from every continent and from regions where they are now, or were in the past, under threat, including Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Bahrain, Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Zimbabwe, China, Myanmar/Burma, Pakistan, Philippines, Turkey, Russia/Chechnya, Belarus, Mexico, El Salvador, as well as from all over Europe and North America. The more than 200 guests strategized over the challenges to freedom of writing and expression. They explored new threats such as digital surveillance, new adversaries in non-state actors and new and old methods of protest and advocacy; they also heard reports of those currently on the frontlines.

While global solutions to these large questions are not easily forthcoming, answers are often found in specific acts of one writer advocating on behalf of another, of one city opening its doors to one writer at a time, of a community gathering and raising a collective voice and finding where to target that voice….[cont]

May 2014: Tunisia could be the first Arab Spring success. But it’s not there yet.

Tunisia has many advantages that set it up well for progress. But the country’s future will not be assured without international support. It must fortify a weak economy, combat crime and terrorism, and continue government reforms.

(Op-ed published in The Christian Science Monitor, May 27, 2014)

Tunis, Tunisia

In Roman times wild animals paced beneath Tunisia’s El Jem colosseum, ready to spring into mortal combat with gladiators – usually slaves fighting for their lives and sometimes freedom – as an audience looked on. Recently I paced the floor of this same amphitheater, trying to imagine its history – and future.

Today, Tunisia is engaged in its own struggle for the life of its new democracy. Though a small country – 64,000 square miles with 11 million people – Tunisia is vital to regional stability. Now this ancient North African country where the Arab Spring began is poised to become the first success in the region – but only if it can shore up a weak economy, curb the dual threats of terrorism and crime, and continue needed government reforms.

Three years after a young street vendor set himself on fire to protest the authorities’ harassment and corruption, three years after the citizens rose up and ejected their longtime autocratic leader, Tunisia has laid the groundwork for its future. In January, the citizenry adopted a new Constitution that was widely debated and passed with the votes of more than 90 percent of the Constituent Assembly. All sectors endorse and are proud of the forward-leaning Constitution, which balances the secular and religious and is looked at as a model for the region.

As a further mark of progress, the Assembly recently passed a law establishing a judicial body to determine the constitutionality of new laws. It will be replaced by a new constitutional court after the next election. This opens the way now for the Assembly to pass a law to set up elections, which are anticipated this year….[cont]

May 2015: No blog posted.

May 2016: Call for Help inside Iran’s Evin Prison

Shared below is a letter that managed to get out of Iran’s infamous Evin Prison from journalist and human rights activist Narges Mohammadi. She is detained on charges of “gathering and colluding to commit crimes against national security” and “spreading propaganda against the system.” According to reports she has also been charged with “insulting officers while being transferred to a hospital” because of her health. Narges Mohammadi is former vice president and spokesperson of the Defenders of Human Rights (DHRC) which represents prisoners of conscience. She is also involved in a campaign against the death penalty in Iran.

Narges Mohammadi

On May 17 the verdict in her case was handed down. Narges Mohammadi was sentenced to five years in prison for “meeting and conspiring against the Islamic Republic,” one year for “spreading propaganda against the system” and ten years for her work advocating against the death penalty. Under Iranian penal code, a person with several jail terms must serve the most severe so she must serve ten years, although sentenced to 16 years total.

Dear members of International PEN,

I’m writing this letter to you from the Evin Prison. I am in a section with 25 other female political prisoners, with different intellectual and political point of view. Until now 23 of us, have been sentenced to a total of 177 years in prison (2 others have not been sentenced yet). We are all charged due to our political and religious tendency and none of us are terrorists.

The reason to write these lines is, to tell you that the pain and suffering in the Evin Prison is beyond tolerance. Opposite other prisons in Iran, there is no access to telephone in Evin Prison. Except for a weekly visit, we have no contact to the outside. All visits takes place behind double glass and only connected through a phone. We are allowed to have a visit from our family members only once a month….[cont]

May 2017: American Writers Museum Launches in Chicago

(Published in World Literature Today, May 10, 2017)

The new American Writers Museum, opening this May in Chicago, celebrates American literature in a lively, interactive space that honors America’s writers past and present.

Located on the second floor of a grand old building on Michigan Avenue’s “Cultural Corridor,” the American Writers Museum is the realization of a seven-year journey that began with a question: Why was there no national museum in the US honoring writers?

Malcolm O’Hagan, a dedicated reader and retired engineer and businessman, had visited the Dublin Writers Museum in his native Ireland and began to talk with friends and professionals about developing an American museum. He brought on writers, scholars, and publishers to develop the idea and curate the selection of writers. All agreed the focus should be on writers no longer living who’ve stood the test of time, but the museum should also celebrate contemporary literature with readings, book signings, and programs.

“I see the museum as a literary jewel box where a visitor can enjoy old friends—the books, words, characters of writers they know and also get to meet new ones,” O’Hagan says. Chicago was selected because of its central location, the support of the city, and its rich literary heritage, which includes writers like Carl Sandburg, Saul Bellow, and Gwendolyn Brooks.

One of the governing principles was not to create a museum for static artifacts—though there will be some artifacts—but a place where readers, writers, and visitors can learn….[cont]

May 2018: Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression

(Below is my talk for the Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression, a conference held every two years, but this year it is being held via video May 26-27. For the first time in 21 years the organizers judged that a gathering in person was too problematic given the arrests and crackdowns on the media. Turkish presidential elections are scheduled for June 24 alongside parliamentary elections.)

I first visited Turkey for the inaugural “Gathering in Istanbul” in March 1997. At the time I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee and joined 21 other writers from around the world. Along with over a thousand Turkish artists and writers, most of us had signed on to be “publishers” for Freedom of Thought, a book that re-issued writings which had violated Turkey’s laws against “insulting the State.” The book included work by noted authors, including celebrated novelist Yasar Kemal. None of us aspired to go to Turkish prison, but we understood the importance of showing up and showing solidarity with our Turkish colleagues. During that Gathering we visited prisons where writers and publishers were incarcerated and visited court rooms where they were charged.

Rally at Istanbul University [includes Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN), James Kelman (Scottish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Kalevi Haikara (Finish PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (WiPC Chair/American PEN with bullhorn), Şanar Yurdatapan (Turkish rights activist and organizer)]

Unfortunately, that opening has closed, and we are here today on video because the biennial ‘Gathering in Istanbul’ for the first time in 21 years is too problematic to hold in Istanbul. The situation for freedom of expression is worse than ever in Turkey with more writers in prison than anywhere else in the world. Depending on the statistics of the day, there are more than 250 journalists and media workers in or facing prison terms, 200 media outlets closed, and thousands of academics and civil servants let go or facing charges….[cont]

May 2019: [Beginning in May, 2019 I began writing a retrospective of work with PEN International for its Centenary so posts were more frequent in 2019-2020. In May 2019 there are two posts in the PEN Journeys and in May 2020 there are four.]

May 2019: PEN Journey 1: Engagement

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

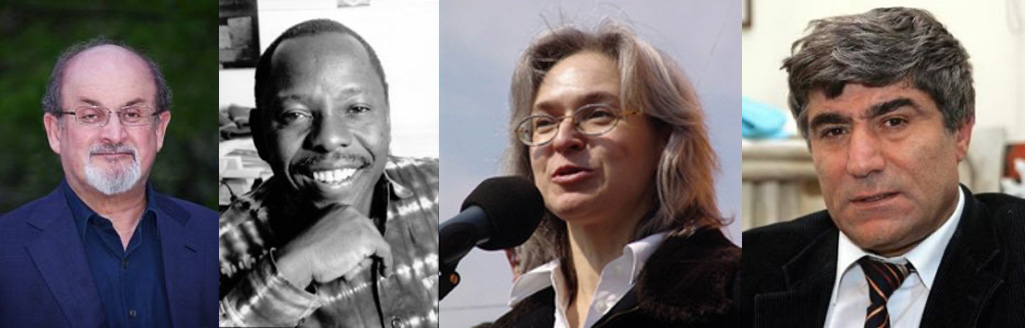

February 13, 1989: I was President of PEN Center USA West and on an airplane when I read that Salman Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses was being burned in Birmingham. The next day a fatwa was issued on Rushdie. What was a fatwa, we all asked at the time, as we, along with PEN Centers around the world, mobilized to protest that a head of state was ordering the murder of a writer wherever he was in the world.

November 10, 1995: As Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, I was standing vigil with others outside the Nigerian Embassy in Washington, D.C. when word spread that novelist and activist Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

October 7, 2006: My phone rang at 7:30 on Saturday morning. I was International Secretary of PEN International, and the International Writers in Prison Program Director was calling to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya had just been shot and killed in Moscow. We all knew Anna—I’d last had coffee with her at an airport in Macedonia. We worked with her on the situation of writers in Russia and Chechnya and had enormous respect for her knowledge and courage.

January 19, 2007: We were about to begin a PEN International board meeting in Vienna when a call came from Istanbul. Hrant Dink had just been shot and killed outside his newspaper office in Istanbul. Dink was an editor of an Armenian paper and a writer whom members of PEN knew well and worked with on freedom of expression issues in Turkey.

Most writers long active in PEN’s freedom-to-write work can tell you where they were when the news broke on each of these cases. They can tell you because the lives of these writers and many others have been critical in the struggle for freedom of expression around the world….[cont]

Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro Wiwa, Anna Politkovskaya, Hrant Dink

May 2019: PEN Journey 2: The Fatwa

It was President’s weekend in the US—between Lincoln and Washington’s birthday, coinciding with Valentine’s Day, 1989. I was President of PEN Center USA West and had just hired the Center’s first executive director ten days before. I’d been working hard with PEN and was also finishing a new novel, teaching and shepherding my 8 and 10-year old sons. For the first time in a year and a half my husband and I were going away for a long weekend without our children. He had also been working nonstop and had managed to clear his schedule.

On the plane to Colorado where we planned to ski, I read that Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses had been burned in Birmingham, England. The next day Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Rushdie. What was a fatwa? The Supreme Leader of Iran was calling for the murder of Rushdie wherever he was in the world, and he was offering a $6 million reward. As information about the fatwa developed, it also included a call for the death of whoever published The Satanic Verses.

I began making phone calls. This was a time before omnipresent cell phones so I had to find phones and numbers where people could reach me. (Usually our vacation dynamic was that my husband was on the phone.)…[cont]

May 2020: PEN Journey 27: San Miguel de Allende and Other Destinations—PEN’s Work Between Congresses

Over the years I’ve used various metaphors to describe PEN International—a giant wheel with 140+ spokes that reach out into the corners of the globe. A vast orchestra with the string, woodwind, brass and percussion sections scattered across the map, directed by local conductors and the Secretariat in London.

PEN’s core is an idea, codified in its Charter, acted upon by writers around the world organized into PEN centers. These writers and centers gather intensity as they work together.

Writers in a country or region or language are empowered to work as a center of PEN by the whole body of centers—the Assembly of Delegates—which vote on a center’s membership at PEN’s annual Congresses. During the months in between, PEN centers act both individually and collectively—celebrating and presenting literature in the many cultures and languages, mobilizing on issues of freedom of expression, acting to preserve and celebrate languages and translation, in particular minority languages, discussing and debating issues of peace, addressing the situation of women writers, and assisting and protecting writers who find themselves in exile. All of this activity between the annual Congresses occurs in the PEN centers and in the work of PEN International’s standing committees and at regional conferences which convene during the year….[cont]

May 2020: PEN Journey 28: Bellagio: Looking Forward—PEN for the 21st Century

In discovering Lake Como in Northern Italy on a walking tour in 1790 poet William Wordsworth called it “a treasure, which the Earth keeps to itself.” Poet Percy Bysshe Shelley declared it “exceeds anything I ever beheld in beauty with the exception of the arbutus islands of Killarney.” He extolled the chestnut, laurel, bay, myrtle, fig and olive trees that “over-hang the caverns and shadow the deep glens which are filled with the flashing light of the waterfalls.” These descriptions from the English romantic poets are matched no doubt by Italian and other poets encountering Lake Como, one of Italy’s largest and one of Europe’s deepest lakes.

Lake Como—“a treasure which the Earth keeps to itself” and the site of PEN International’s strategic planning conference, July 2003

Lake Como is one of my favorite places so meeting for an International PEN strategic planning conference above the shimmering Y-shaped lake set among the Alpine foothills was an ideal working vacation the summer of 2003. I participated as a PEN vice president and a trustee of the International PEN Foundation and former Writers in Prison Committee chair, along with International PEN’s President Homero Aridjis, International Secretary Terry Carlbom, Treasurer Britta Junge Pedersen, current and past board members, other trustees of the International PEN Foundation, several vice presidents and the standing committee chairs.

Twenty-six of us from 14 countries gathered to discuss the changed global context for PEN, which had grown from 95 to 134 centers in the last 14 years, and to consider the demands on this organization dedicated to the role of writers in promoting intellectual co-operation, tolerance and pluralism in the world….[cont]

May 2020: PEN Journey 29: Mexico City and the Road Ahead—Part I, Form

A PEN International World Congress is a hybrid—a mini-UN General Assembly with delegates sitting at tables behind their center’s (and often country’s) name plates discussing world affairs that relate to writers; an academic conference with panelists addressing abstract philosophical themes; a literary festival with writers reading their poetry and stories and sharing books, and finally a civic engagement with resolutions passed on global issues which are then delivered, sometimes by a march or candlelight vigil to a country’s embassy that is oppressing writers.

Heads of state and UN officials frequently visit and/or speak at PEN Congresses depending on the openness of the host country; esteemed writers, including Nobel laureates, and former PEN main cases are often guests. The Congress’ size varies depending on the resources available, but the financial commitment is out of reach for many PEN Centers.

The 2003 International PEN Congress in Mexico City was celebrated as the First Congress of the Americas. Hosted by Mexican PEN, it was also supported by Canadian PEN, Quebecois PEN, American PEN, and the Latin American PEN Foundation. It was the final Congress under the presidency of Mexican poet and novelist Homero Aridjis. Organized around the theme of “Cultural Diversity and Freedom of Expression,” the 69th Congress welcomed delegates from 72 PEN Centers from every continent except Antarctica….[cont]

May 2020: PEN Journey 29: Mexico City and the Road Ahead—Part II, Substance

…As well as reporting on the welcoming of new centers, Part 1 of PEN Journey 29 recounted an historic Charter amendment, major rules and regulation changes and a strategic plan—the nuts and bolts and essential frame for any organization, especially one as complex as International PEN as it sought to modernize its governance and structure. In Part II the focus turns to the substance of PEN’s work and of the 2003 Congress.

The final gathering under the presidency of Mexican poet and novelist Homero Aridjis, PEN’s 69th World Congress hosted more than 250 participants, speakers and guests, including Nobel laureate and PEN International Vice President Nadine Gordimer and also listed on the literary programs Nobel laureate and former PEN International President Mario Vargas Llosa and many writers from the Americas—Michael Ondaatje, John Ralston Saul, Francine Prose, Andrés Henestrosa and writers from at least 12 indigenous regions and languages in Mexico—Huichol, Maya, Mazahua, Mazatec, Mixtec, Náhuatl, Tenec, Tojolab’al, Tzotzil, Wuirárica, Yoleme, Zapoteca.

PEN International 69th Congress. L to R: Deborah Jones (PEN USA West), Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Isobel Harry (Canadian PEN), Terry Carlbom (PEN International Secretary), General José Francisco Gallardo (former PEN main case) and his family; Nadine Gordimer (PEN International Vice President) and General Gallardo; General Gallardo, translator, and Jens Lohman (photos courtesy of Sara Whyatt)

Homero Aridjis noted: ‘The Congress programs explore the literature of the Americas, of Canada, the United States and Latin America, shining a particular light on the indigenous literatures which are so essential to understanding the cultural map of our continent from Chile to Canada.’…[cont]

PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move: West to East

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I have attended 32 International PEN Congresses as president of a PEN Center, often as a delegate, as Chair of the International Writers in Prison Committee, as International Secretary and now as Vice President. The number surprises me when I count. The Congresses have been held on every continent except Antarctica. Many were grand affairs where heads of State such as Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia, Angela Merkel in Germany, Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal greeted PEN members. Some were modest as the improvised Congress in London in 2001 when PEN had to postpone the Congress planned in Macedonia because of war in the Balkans. PEN held its Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia the following year. At these Congresses writers from PEN centers all over the globe attended. Today PEN International has centers in over 100 countries.

Among the more memorable and grand was the 54th PEN Congress in Canada, held in September 1989 when PEN still held two Congresses a year. The Canadian Congress, staged in both Toronto and Montreal by the two Canadian PEN centers, moved delegates and participants between cities on a train. The theme—The Writer: Freedom and Power—signaled hope at a time when freedom was expanding in the world with writers wielding the megaphone.

54th PEN Congress in Canada, 1989. Front row: WiPC chair Thomas von Vegesack, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman and PEN USA West Executive Director Richard Bray. Back row: Digby Diehl (right) and other delegates.

The literary programs included luminary writers from over 25 countries, including Margaret Atwood (Canada), Chinua Achebe (Nigeria), Anita Desai (India), Tadeusz Konwicki ( Poland), Claribel Alegria (El Salvador), Margaret Drabble (England), Michael Ignatieff (Canada), Ama Ata Aidoo (Ghana), Derek Walcott (St. Lucia), John Ralston Saul (Canada), Duo Duo (China), Harold Pinter (England), Tatyana Tolstaya (USSR), Alice Munro (Canada), Wendy Law-Yone (Burma), Larry McMurtry (USA), Emily Nasrallah (Lebanon), Yehuda Amichai (Israel), Maxine Hong-Kingston (USA), Michael Ondaatje (Canada), Nancy Morejn (Cuba), Jelila Hafsia (Tunisia), Miriam Tlali (South /Africa), and dozens more, and other writers listed in absentia such as Vaclav Havel (Czechoslovakia) and writers from Iran, Turkey, Hungary, South Africa, Morocco and Vietnam. PEN members and delegates attended from at least 57 PEN centers around the world.

The new PEN International President Rene Tavernier, a poet who had been active in the French resistance during World War II, hailed the importance of the writer’s role in upholding freedom of expression around the globe and in confronting central power which restricted individual voices. PEN’s and the writer’s only weapon was the word, he said, and the word must be used in service of “creative intelligence, human rights, lucidity and hope.” Though the twentieth century had seen “the growth of new and atrocious ideologies with their police forces and concentration camps, they could not change the spirit of man, which is what PEN defends,” he said. PEN’s concern was literature and ideas and conversations among writers, who may not always agree.

A goal of the Congress was to expand dialogues among people, especially in Muslim communities in the wake of the fatwa and to expand PEN’s reach into Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. Today PEN centers in those areas have grown exponentially with 33 centers in Africa and the Middle East and 19 centers in Latin America, though participation from these centers in global forums still remains challenging.

Another outcome of the Congress was the formation of the PEN Women’s Network, a precursor to the Women’s Committee established as a standing committee of PEN two years later at the 1991 Vienna Congress. The Canadian Congress organizers had balanced literary panels and discussions among men and women, a response to the growing voice of women in PEN and to the 1986 New York Congress where men dominated the forums. Some opposed a Women’s Committee, including English PEN which voiced concern that it would fragment and divide members when the goal of PEN was to bring people together. English PEN already operated under a guideline that balanced men and women in leadership. PEN International Vice President Nadine Gordimer wrote that she had “more pressing obligations here, at home in South Africa, towards the needs of both women and men who are writers under our difficult and demanding position, beset by censorship, harassment, and lack of educational opportunities common to both sexes.” But she added that she hoped if a committee did form, it would be in touch with all South African writers.

PEN USA West presented a resolution on South Africa at the Congress, protesting the arrest and treatment of a number of writers, including our honorary member. The resolution passed unanimously in the Assembly of Delegates.

My fellow delegate and I also joined American PEN as well as Canadian PEN, Hong Kong and Taipei PEN in a resolution protesting the “slaughter of Chinese citizens peacefully assembled in and around Beijing’s Tiananmen Square” three months before and the arrest of writers, including Liu Xiaobo and over 20 others. It was feared some of the China PEN members might be under threat. Neither the China Center nor the Shanghai Center were present at the Canadian Congress, but they had been in touch with PEN International. In an official communication the Shanghai Center protested that China was being slandered abroad. Representatives from the two Chinese Centers had demanded an apology from PEN International because poet Bei Dao had been allowed to address the Maastricht Congress (see PEN Journey 3) and they continued to argue that PEN’s main case Wei Jingsheng was not a writer. An apology was not offered, and the resolution protesting the killings and arrests after Tiananmen Square passed with one abstention. Delegates from the China Center and Shanghai Center didn’t return to a PEN Congress for the next two decades, but in the intervening years, individual centers and members such as Japanese writers stayed in touch. In 2001 an Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) formed and gave a place for Chinese writers inside and outside of China to communicate with discussion and debate on freedom of expression and democracy. PEN currently has more than half a dozen centers of Chinese writers, including the China, Shanghai, ICPC, Taipei, Hong Kong, Tibet, Uyghur, and Chinese Writers Abroad centers.

The challenge for PEN has always been how best to use its formal resolutions, written in the language of the United Nations. These are passed then directed to the respective governments, to United Nations forums and to embassies and officials in the countries where PEN has centers and to the media. The effort begins at the PEN International office and then fans out through the centers. The impact of the resolutions vary according to country and to the direct advocacy efforts. However, the climate for such resolutions has altered over the years, and it is an ongoing question what is the most impactful method for effecting change.

At the Canadian Congress the situation in Myanmar/Burma was also highlighted. Our center, along with Austrian, Australian (Perth), and Canadian centers presented a resolution protesting the slaughter of Burmese citizens and the wholesale arrests and imprisonment without trial of citizens, including writers, after the imposition of martial law. I met one of these writers—Ma Thida—in London years later after PEN had advocated aggressively for her release. She’d spent almost six years in prison. A physician, writer and editor and an assistant for Aung San Suu Kyi, she remained committed to freedom for her country. It took another 15 years before the Myanmar government eased restrictions and a civilian government took over. When the political situation in Burma/Myanmar began to open, Ma Thida, Nay Phone Latt and other writers, many of whom had been in prison, formed a PEN Myanmar Center which joined PEN’s Assembly at the 2013 Congress in Reykjavik, Iceland. Ma Thida was its first president, and she now serves on the International Board of PEN.

Ma Thida and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman at the PEN Congress in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan in October 2014

For me, the outward facing Canadian Congress mirrored my own preparation for moving with my family to London three months later in January 1990. It was a fortuitous time to live in Europe as Eastern Europe was opening to the West. Six weeks after the PEN Congress, East Germany announced that its citizens were free to cross into the West, and the Berlin Wall began to crumble figuratively and literally as citizens used hammers and picks to knock down the looming concrete structure. In fall 1990, I took my sons, ages 10 and 12, to East Berlin, and we too climbed up on ladders with metal rods and knocked down the wall, chunks of which we still have.

Joanne and sons Elliot and Nate at the Berlin Wall, Fall 1990

At the Canadian Congress, PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) Chair Thomas von Vegesack asked that a sub-committee be formed to assist in fundraising. Eight centers—Australian (Perth), Canadian, Swedish, Norwegian, West German, English, American and USA West agreed to help. Because I was moving to London where PEN International was headquartered, Thomas asked if I would head the effort. I told him I wasn’t able to do so but agreed to take on the interim position and help him find a chair and then agreed to take on the task of getting PEN International charitable tax status. I assumed the latter mission would be fairly straightforward, a matter of finding the right law firm to assist. Little did I know the complications of British charitable tax law. Eventually Graeme Gibson, president of PEN Canada, novelist and partner of Margaret Atwood, agreed to head the development effort.

After I arrived in London, I found a law firm. Charitable tax status would relieve PEN of tax bills it found hard to pay and also help with fundraising, but so far PEN had not been able to secure the charitable status. Thomas and I, along with the International Secretary Alexander Blokh, Treasurer Bill Barazetti and Administrative Secretary Elizabeth Paterson met frequently at the PEN International offices at the top of four (or was it five?) very steep flights of stairs in the Charterhouse Buildings where we worked on what turned out to be a two-year project that included the establishment of the International PEN Foundation. The Foundation was allowed to raise tax-exempt funds for the “charitable” work of PEN which could not include perceived “political” work, but only the “educational” aspects.

It took a young American who didn’t know it was impossible to do what we have not been able to do, Antonia Fraser said to me as she joined the first board of the International PEN Foundation in 1992. In a way she was right for I had no idea the complexity of British tax law, quite different than America’s. I wasn’t prepared for the sets and sets of documents and negotiations, the time required to set up a separate organization; on the other hand, the effort opened up the workings of PEN International to me and introduced me to friends I’ve maintained over the decades who also worked on the project. On the Foundation board with me were a majority of British citizens (and PEN members), including Antonia Fraser, Margaret Drabble, Buchi Emecheta, Andre Schiffrin, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson and later Ronald Harwood as well as a few other international members, PEN’s International Secretary, Treasurer and the new PEN President Gyorgy Konrad.

Harold Pinter’s play Moonlight premiered as the first fundraising event of the International PEN Foundation on October 12, 1993 at the Almeida Theater. Dramatically, the lights of the theater burnt out just before the performance, and the play was performed by candlelight.

First International PEN and PEN Foundation brochure.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 5: PEN in London, Early 1990’s

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.