Finding Light in a Dark Time

I’ve just returned from PEN International’s 90th World Congress in Oxford, England whose theme was “Writers in a World at War.” PEN originally planned to celebrate its Centenary in Oxford in 2021, but the global pandemic disrupted that gathering. This 90th Congress was co-hosted by English PEN, and while it was smaller than the planned Centenary, there were delegates from 80 PEN centers around the world and 20 more centers represented on Zoom. More than 200 writers participated.

Oxford, England at dusk

PEN International’s congresses have occurred annually except during World War II. The congress is a time when the conversation is live among writers from almost 100 nations in the more than 130 PEN centers. Literature is shared. Formal discussions focus on the challenges for writers at risk, in prison and threatened by authoritarian governments, the challenges of peace and displacement for those in conflict areas, the challenges of linguistic rights and translations and the ongoing challenges for women around the globe. These are addressed through PEN’s four standing committees—the Writers in Prison Committee, the Peace Committee, the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, and the Women Writers Committee. At this 90th Congress a new standing committee of PEN International was formed for the first time in 33 years. The committee will develop and give voice to younger writers and is based on the original premise of PEN’s founders for a Tomorrow Club.

PEN operates at both an individual and a global level. The work focuses on the individual writers in prison and at risk in countries such as China, Turkey, Vietnam, Myanmar, Cuba, Guatemala, Belarus, Russia, Egypt, Iran and others. Members write to their fellow writers in prison, to their governments, to the members’ own governments; they lobby on the writers’ behalf, celebrate their writing which the government has suppressed. At a global level PEN International speaks out at the United Nations Human Rights Commission and other forums seeking and urging pathways to free expression and to peace.

This later action via the Peace Committee is often more challenging and taxing to PEN’s mandate. PEN International President Burhan Sönmez noted, “War is the darkest word in every language. While peace is the longest word. Because it never comes to an end in any language.”

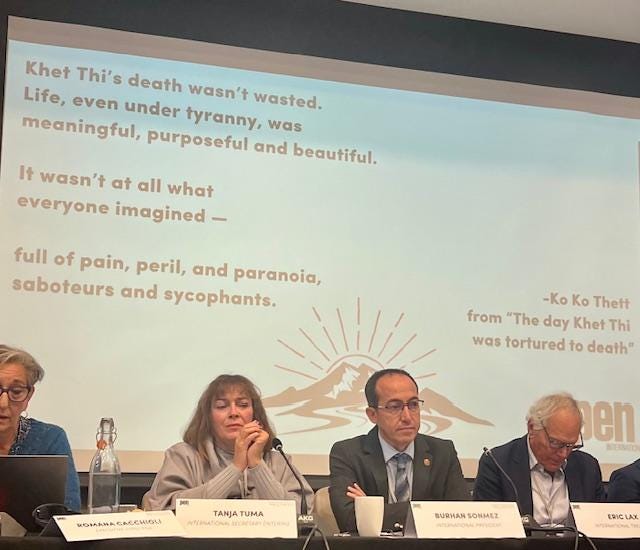

PEN International: (L to R) Executive Director Romana Cacchioli, International Secretary Tanja Tuma, PEN International President Burhan Sönmez, Treasurer Eric Lax

At the 90th Congress the lines of tension heightened as the issues of peace in Israel and Palestine and Gaza arose. The challenges in the Middle East have tested PEN and its Charter before. PEN’s Charter urges members to “use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people” and to “do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.” At the same time “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression….”

One of the panels at the Congress was devoted to PEN’s Charter, which novelist and poet Ben Okri described as “one of the great documents of the century, a foundational document.” Linked here, the PEN Charter was one of the documents studied in the development of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Drafted in the wake of World War I and World War II, the governing principle of PEN’s Charter is that “Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals. In all circumstances and particularly in time of war, works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large should be left untouched by national or political passion.”

How this mandate is fulfilled through resolutions and statements in a time of war as is occurring in the Middle East can challenge members. There are those who resist PEN stepping into geopolitical strategies and those who think PEN must not remain silent on these specific issues. Is peace just the cessation of hostilities or the resistance to those who would oppress? A resolution was finally voted on and passed, though not unanimously but with an understanding that the principles of PEN keep us together.

I quote here the words of former PEN International President, playwright Ronald Harwood, who I had the privilege of serving closely with during our shared terms at the Secretariat and with whom I agreed at the time and still in this more activist era. At a fraught Congress during the war in the Balkans in 1993, Ronny noted to the Congress:

“The world seems to be fragmenting; PEN must never fragment. We have to do what we can do for our fellow-writers and for literature as a united body; otherwise we perish. And our differences are our strength: our different languages, cultures and literatures are our strength. Nothing gives me more pride than to be part of this organization when I come to a congress and see the diversity of human beings here and know that we all have at least one thing in common. We write…We are not the United Nations…We cannot solve the world’s problems…Each time we go beyond our remit, which is literature and language and the freedom of expression of writers, we diminish our integrity and damage our credibility…We don’t represent governments; we represent ourselves and our centers…We are here to serve writers and writing and literature, and that is enough… And let us remember and take pleasure in this: that when the words International PEN are uttered, they become synonymous with the freedom from fear.”

Friends and colleagues at the PEN International 90th World Congress in Oxford, England, September 2024

Join me on Substack