October: The Cruelest Month or Prelude to Halloween, Holidays and Spring?

“April is the cruelest month,” T.S. Eliot wrote in the opening of The Waste Land,* published 99 years ago in October,1922. He characterized: “Winter kept us warm…” and “Summer surprised us,” but autumn isn’t mentioned in his epic poem.

Decades later a very different apocalyptic voice Hunter Thompson declared, “October is the cruelest month,” at least in any election year because “by then, the pain is so great that even the strong are like jelly and time has lost all meaning for anybody still involved in a political campaign.” **

In October in the U.S. this fall, there are only a few state and gubernatorial elections, but they will be watched like an oracle’s lots to predict the future.

Photo credit: Julia Malone

At its most literal October is a month when seasons change. In the northern hemisphere the foliage turns vibrant orange, red and yellow; the air grows crisp, and the sky darkens earlier each day. For the purpose of this blog, October is one of the few months when I’ve managed to post every year since 2008 in settings from over a dozen countries—Holland, Malawi, Turkey, England, Belgium, Columbia, Spain, Morocco & the Western Sahara, Kyrgyzstan, Canada, Lebanon, Japan, Senegal and the United States. The posts focus on issues of freedom of expression, events and congresses of PEN International, on certain shifting tectonic plates current and historic, and on U.S. Presidential elections.

Collecting here another retrospective of a month, I’ve gathered October posts since 2008 in one space. This monthly exercise began in March 2021 when travel was curtailed during the pandemic and past wanderings seemed more interesting than musings from my chair by the river on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The exercise will allow me at the end of 12 months to have all 178 blog posts easily accessible with only a few clicks—for what purpose, I don’t yet know other than the convenience of considering thoughts and events over the last dozen years.

For this month I offer my own variation: October is the morphing month, or perhaps the bridging month anticipating the future.

*T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land

**Hunter S. Thompson, Generation of Swine: Tales of Shame and Degradation in the 80‘s.

October 27, 2008: Election: Growing Into Ideals

I went early on election day 2000 to vote at the polling station in the church on the cobblestone street in my neighborhood. The lines snaked down the block as neighbors read their morning papers, chatted, visited each other with their dogs on leashes and waited to get inside. After I voted, I went to the airport, and before the polls closed, I flew out to Africa.

When I arrived in Amsterdam, the big television screen outside the airport announced that Albert Gore was the next President of the United States. I went to sleep for a few hours in an airport hotel before my connecting flight. When I awoke, the television announced George Bush was the next President of the United States. I boarded the plane, arrived hours later in Malawi and learned that the United States did not yet have a president.

For the next ten days in Malawi and Ethiopia I attended meetings, visited schools in villages and at every opportunity tried to find a BBC broadcast to let me know who was the next President of the United States. The local press began to write stories to inform Americans how to conduct an election. The banana republic of the United States of America made people smile as everyone watched all the machinery of government at work as the country tried to sort out its leadership. When I arrived home, there still was no new President.

Indications are that the election of 2008 will not be as close, but it too will be a historic election. Whoever wins, barriers will fall, and the profile of leadership at the top will change in the United States. History will only really be made, however, as the sentiments are shed which once barred women, African Americans and others of color from opportunities.

As we’ve watched what has seemed like an endless electoral process over more than 20 months, we have also been watching the country coming to terms with itself and its ideals and its history. The ugliness and slurs that have accompanied part of this election for the most part have been dismissed by the electorate who wants more and insists that we grow up and into our national ideal of all men and women as created equal.

The other day I was discussing with several young voters why this election is so unique. In addition to the specific ground-breaking profiles of an African American candidate for President and a woman candidate for Vice President, this election in the U.S. is the first in over 50 years when no candidate is a sitting President or Vice President. The field and the possibilities are wide open.

I plan to stay around this year and watch the returns. In 2004, I was also in Washington, watching the returns with friends. The lead in that election changed several times. At one point I looked around the room of experienced Washingtonians, many couples in long marriages who worked at senior levels in and outside of government. I realized that almost every couple in the room had canceled each other’s votes. When I tell that to friends from other countries, they are always surprised, yet it is more common than one might expect in Washington. For all its partisanship, the city is peopled with professionals who may vote on one side, but in their professional lives work to find ways to cooperate. They understand that for the country to run well, everyone has to work together.

I’m hoping this year, whoever is the victor, he/she will have the benefit of all the citizens in the difficult tasks ahead. If not, then I’ll look forward to reading the press in other countries to advise us how to do that.

October 27, 2009: Yellow Geranium in a Tin Can

From the November/December 2009 Issue of World Literature Today as the Introduction to the Special Feature, “Voices Against the Darkness: Imprisoned Writers Who Could Not Be Silenced”

The prisoner Halil

closed his book.

He breathed on his glasses, wiped them clean,

gazed out at the orchards,

and said:

“I don’t know if you are like me,

Suleyman,

But coming down the Bosporus on the ferry, say

making the turn at Kandilli,

and suddenly seeing Istanbul there,

or one of those sparkling nights

of Kalamish Bay

filled with stars and the rustle of water,

or the boundless daylight

in the fields outside Topkapi

or a woman’s sweet face glimpsed on a streetcar,

or even the yellow geranium I grew in a tin can

in the Sivas prison—

I mean, whenever I meet

with natural beauty,

I know once again

human life today

must be changed . . .”

—Nâzım Hikmet, Human Landscapes (1966)

In 1938 the renowned Turkish poet Nâzım Hikmet (1902–63) was sent to prison, charged with “inciting the army to revolt,” convicted on the sole evidence that military cadets were reading his poems. He was sentenced to twenty-eight years but was released twelve years later in 1950. His “novel” in verse, Human Landscapes from My Country, was written in prison, featuring Halil, a political prisoner, scholar, and poet who was going blind (see WLT, October 2003, 78).

One of the cadets reading Hikmet’s poems was the young writer Raşit, who met the senior poet in prison. Raşit helped care for Hikmet, and Hikmet mentored Raşit, who went on to become famous in his own right as the novelist Orhan Kemal. The friendship of the two men endured past prison, as Maureen Freely’s article “The Prison Imaginary in Turkish Literature” (page 46) chronicles.

In this issue of WLT, stories, essays, and poetry from Turkey, Burma/Myanmar, Iran, South Africa, Libya, and Iraq show prison as a cage, a crucible, a classroom, a stage, a fraternity from hell. The challenge for the writer in prison is to survive and to keep writing….[cont]

October 22, 2010: War and Peace Redux

Every decade or so I reread Tolstoy’s War and Peace. I have just embarked again on this pleasure. I don’t put the rereading on my calendar. Instead the need arises; I can’t say exactly why, but I find myself wanting to reread this great novel, often because of wrestlings in my own work or because of the need for an ordering of the universe of politics, history, art and spiritual quest. The return is always a homecoming, a touchstone.

Authors are often asked, what is your favorite book? Mine, modestly, is War and Peace. I admire Tolstoy’s ability to weave large historical and political themes with compelling personal dramas. I admire the surprises of character and circumstances that occur, to which one responds, “I didn’t see that coming, but of course, that is what he/she would do or what would happen.” This verisimilitude and recognition of the truth beneath the surface of events and personalities is one of the ingredients of great literature.

Recently, I was asked by an acquaintance for advice on how to lead a discussion of a novel in a book group. I wasn’t part of the group and hadn’t read the novel, but I offered what I look for both in reading and in writing. I consider three circles of narrative. The inner circle: the essence is the personal story and conflict of the main characters. That conflict is reflected in the story of the community around them–the second circle. And in novels with large templates and scope, the conflict will then be seen in an outer circle of narrative in the wider society and history.

At its simplest, the struggles toward love, individual choice and liberation are the story of Natasha, Pierre and Andrei in War and Peace, of Elizabeth and Darcy in Pride and Prejudice, even of Scheherazade in Arabian Nights as their societies also struggle towards change. This of course is the simplest of paradigms, but perhaps useful.

I reread War and Peace slowly. The pleasure of reading endures scene by scene—one scene a day—so that the language, the characters, and the story are a small serving of art to start the day. However one’s day unfolds, whatever successes or lapses, there is the evidence of this ideal achieved and the promise of beauty and order to be realized.

In this space I hope you’ll share the books and narratives that are your touchstones.

–Written at a bistro by the fire near the Grand Place in Brussels on a chilly October afternoon, looking at passersby bundled in parkas and strolling among the red and green stalls and the sand-colored buildings boasting flags at the onset of winter in Northern Europe.

October 27, 2011: Eat, Remember, Hope

London:

Memory accelerates as I look at the wet London street through the window of Sticky Fingers restaurant. For six years Sticky Fingers was our family gathering place and adopted kitchen. We lived nearby, and I would often claim a booth by the window where I ate lunch, spread out my papers and wrote through the afternoon. At the end of the school day and sports practices and skateboarding excursions, my sons would appear and plop down on the other side of the booth and order burgers or fries or pecan pie, and we’d share our day then walk home together, often with a bit of takeout for dinner.

We lived in London during a time of shifting tectonic plates under the power structures of Europe. When the Soviet Army finally yielded to the people in Parliament Square with Boris Yeltsin standing on a tank, I shared the news at Sticky Fingers.

Now these sons are grown with their own families starting. As I sit in a corner by the window today, I recognize no one in the restaurant, but I still write to the rhythm of rock and roll and watch the next generation of students pour in after school. Because this is an afternoon committed to finishing this month’s blog post, I allow my mind to wander and gather the disparate thoughts of the month.

It has been a month of travel and meetings and optimism in unexpected places. I’ve been in Colombia where the new President Juan Manuel Santos has announced major land reforms and human rights policy. Human rights organizations that have tracked Colombia for years, now hope that after decades of murder, kidnappings and drug trafficking, a significant change may be at hand for the country. The effort to return land to the millions of peasants who have been displaced by violence is still in early stages and fragile; proponents of redistribution have been killed this year. Yet with one million of the five million hectares allegedly returned and with an elected government determined not to let fear rule, there is reason to hope.

Brussels:

In Brussels I return to a restaurant of rough wooden tables and stools with a large fireplace in the middle, situated in a corner of the Grand Place. I’m here for other meetings, but use the afternoon to write and thread strands of thought through the needle of this blog post.

In these meetings, which examine conflicts around the world, Myanmar/Burma is pointed to as a country, hardly democratic and long closed and ruled by autocratic military leaders, where the new civilian government is taking steps towards reform. The release of some political prisoners and the overtures to Aung San Sui Kyi are positive steps. The government is being urged to continue opening up reform at the same time human rights groups are monitoring carefully the military, which operates outside the authority of the civilian government under the new Constitution and continues to threaten ethnic minorities.

Hope spins a fragile thread between these two countries halfway around the world from each other, one a democracy, the other a faux democracy. But one may hope that each is bending the bow of history towards greater freedom.

***********************

The pleasure of this relatively new form—the blog post—is that it can be informal; it can be self-conscious; it can be whatever the writer wants it to be…. so I suggest this month’s be interactive and urge friends and readers to link memory and world events and pockets of optimism together and leave comments.

October 26, 2012: A Visit to the End of the World

I visited the end of the world this week, at least the spot on the earth where the ancient Romans believed the sun left the earth and the known world ended. The AC 552 highway takes you there in four lanes with possible detours through charming fishing villages along the coast of Galicia. If you stand on the granite cliffs of Finisterre, Spain looking west, you see the billowing Atlantic and can understand the Roman’s perspective for nothing lays beyond, at least nothing one could see or travel to in the ships of their day.

The Romans called the spot the Cape of Death since the sun died there. It was also a place of numerous shipwrecks on the jagged rocks reaching out in a finger hook into the sea before a lighthouse was built centuries later. The Greeks had denominated another spot on the earth, Mount Hacho in Spanish Morocco, as the place where the world ended because that was as far as their eyes could see.

Located on Costa da Morte, the Coast of Death, Finisterre is the ultimate destination for thousands of pilgrims each year who make the journey first to Santiago de Compostela, and then the hardiest continue and walk the additional 90 km. Tradition calls for the pilgrims to burn their clothes and/or boots as a symbol of starting anew. The wisdom is that the most difficult part of the journey is yet ahead of them, the return journey home to a new life.

Since the ninth century when a hermit allegedly found the grave of the Apostle James who had preached in Spain, been beheaded in Jerusalem and then returned by his disciples to Spain, Santiago de Compostela has been the destination of millions of pilgrims worldwide. These days some of the pilgrims appear to be both on a spiritual quest and an athletic adventure, with many combining the two. The caminos (roads) of the pilgrimage vary from 70 km to 1300 km and are traveled mostly on foot, though some pilgrims travel by car.

A journey of the mind can begin by a journey of the feet as thought opens and contemplates vistas not obvious to the eye and beyond perceived earthbound realities.

Finisterre in fact was not the end of the world. Centuries later, leaving from Spain’s southern ports, three and four-masted ships chased the sun as it moved towards the horizon. Christopher Columbus stood at the prow, sailing with his own misconceptions about what lay beyond, but with a knowledge of trade winds that allowed him to arrive and return four times to the New World out there.

It is easier to look back than to glimpse what lies ahead, but on the wind carved summit of Finisterre high above the Atlantic coast, the visitor can almost see the curve of the earth and imagine new worlds without and within.

October 15, 2013: The Last Colony?

The desert stretched out like a beige patterned quilt as far as the eye could see. The pattern looked like birds’ wings or boomerangs in the sand as the plane descended, then the swirls of sand resolved into rocky ground. In the distance a few concrete buildings rose around the pink watch tower of the airport as I landed in Laayoune in the Western Sahara.

A 103,000 sq mi stretch of desert and coastline twice the size of England, larger than all of Great Britain, the Western Sahara is called by some “the last colony.” Extending south between Morocco and Mauritania with almost 700 miles of coast edging the desert, the region has been in a political quagmire for the last four decades. Spain and Mauritania renounced their claim to the area in the late 1970’s, leaving only Morocco and the indigenous Sahrawi’s in dispute.

In February 1976 the Sahrawis declared a sovereign state, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). For almost 16 years (1975-1991) Moroccan forces and the Sahrawi indigenous Polisario Front engaged in armed struggle. For the next 22 years the United Nations has overseen a political limbo. A referendum on independence was promised but has been stalled year after year.

I first became interested in the Western Sahara in the early 1990’s when chairing PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. The stories of torture and the conditions in the prisons of the Western Sahara were as grim as any I encountered. Many died and never made it out of the prisons, which were run by the Moroccan security forces. There were also bleak reports from prisons run by the Polisario rebels. I still remember stories of writers who took their bar of soap they were given each month and wrote poems on their trousers. The writers then memorized each other’s poems as a way of staying sane. They also scoured the prison yard in the one hour they were given each day and found scraps of paper and used coffee grounds to write their forbidden verses. Their stories demonstrated how one endured—through fellowship and a flight to the imagination.

Since that time the armed conflict has officially ceased; Morocco has granted amnesties, and most of the prisons have allegedly been closed, but there are still reports of “black jails” with grim conditions even in the capital. There are large areas where no one is allowed to visit.

My visit was brief, the visit of a tourist. I hired a taxi recommended by the small parador where I stayed, the hotel itself recommended by a friend of a friend who worked at the U.N. My driver spoke Spanish and Arabic, some French and little English. I speak English, some French, less Spanish and very limited Arabic, but we managed. I asked him to show me around the city then take me into the desert and then to the beach.

Those living in Laayoune are living their regular lives, women in long djellabas with head scarves, children going to school—you can hear their chatter and laughter on the streets—men also in djellabas or slacks selling in the shops and markets. But the area is a high security zone. The U.N. and the Moroccan security are present, and travel is restricted. No one is allowed too far east where a giant man-made sand berm separates the Moroccan-dominated region from the smaller Sahrawi Polisario region near Algeria. Land mines are said to be scattered throughout the no man’s land in between.

In my 24 hours in the capital Laayoune, a city of around 200,000 with 70% of the Western Sahara’s population, I was stopped at six checkpoints. Two were on the way to the desert where a two-lane road stretched through the sand and rock. Any other journey in this area would need to be made with an off road vehicle or on a camel, but I saw only a few camels….[cont]

October 7, 2014: PEN on the Plains of Central Asia

PEN International’s 80th Congress opened with galloping horses across the majestic plains of Central Asia’s Kyrgyzstan this past week when the 200 plus delegates from 73 PEN centers around the world encountered “Kurmanjan Datka: Queen of the Mountains” the epic new film featuring Kyrgyzstan’s national heroine. The cinematically stunning drama spanned the late18th to 19th century when the modern nation formed, led by a woman—wife, widow and mother—in a time when women had no rights, when enemies threatened on all sides. The drama ended with Russia’s annexation of the region.

A hundred years later PEN delegates gathered in Bishkek for PEN’s annual Congress whose theme My language, my story, my freedom included discussion, debate and advocacy on issues of free expression. PEN called for release of Uzbek writer Azinjon Askarov from a Kyrgyz prison, Vladimir Kozlov from Kazak prison and Ilham Tohti, who was recently given a life sentence in China for alleged “separatism.” These three individuals were featured with empty chairs at the Congress and represented the more than 900 writers, journalists, publishers, editors and bloggers listed in PEN’s case list and for whom PEN advocates.

Kyrgyzstan is considered the freest of the Central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union, the only republic that could have hosted a PEN Congress, but it is still challenged with ethnic conflicts and with repression of certain minorities, including those from the LGBT communities. The influence of the Russian Federation, including its Law of False Accusation and criminal defamation and laws against “gay propaganda,” the influence of radical Islam and ethnic conflicts affect free expression in the country, according to Marian Botsford Fraser, the Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee.

Before the Congress, PEN International’s President John Ralston Saul and a delegation visited neighboring Kazakhstan and met with the President’s office there to present PEN’s concerns, especially for imprisoned writers Vladimir Kozlov and Aron Atabek. In Bishkek a delegation met with the President of Kyrgyzstan on PEN’s issues and with the federal Prosecutor on the case of Azinjon Askarov….[cont]

October 23, 2015: Life instead of Death…Rationality instead of Ignorance

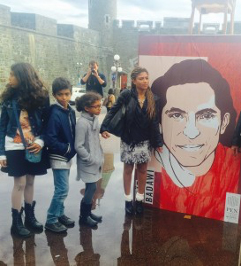

Of all the lively discussions, the literary evenings, multiple resolutions generated at PEN International’s 81st Congress last week in Quebec City, the image that stays in my mind is of the petite wife and children of Saudi blogger and editor Raif Badawi standing in a puddle on the plaza by his picture in the early morning, along with delegates from PEN centers around the world.

His wife and children now live in Quebec, which has also offered Raif Badawi a home, but he remains in a Saudi prison with a ten-year sentence and 950 more lashes of punishment, then a decade long ban on travel, all for setting up a digital forum to encourage social and political debate within Saudi Arabia. He has been found guilty of “insulting Islam” and “founding a liberal website.”

The PEN Congress, which hosted writers from 84 centers in 73 countries, featured three writers with “empty chairs,” including Raif Badawi, Eritrean poet, critic and editor Amanuel Asrat and murdered Honduran journalist Juan Carlos Argenal Medina. PEN called for the release of Badawi and Asrat and justice for Medina. It also targeted the cases of writers imprisoned, threatened, killed or at risk in Bangladesh, China, Cuba, Eritrea, Honduras, India, Iran, Mexico, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Tibet, Turkey and Vietnam.

Badawi’s message via his wife to PEN members after receiving an earlier PEN Canada One Humanity Award was: “We want life for those who wish death to us, and we want rationality for those who want ignorance for us.”

October 3, 2016: Building Literary Bridges: Past and Present

Gathered in the ancient city of Ourense, Spain in the heart of Galicia, writers from around the world celebrated history, debated the present and committed to the future of literature and freedom of expression at PEN International’s 82nd Congress organized around the theme “Building Literary Bridges.”

Two hundred poets, novelists, dramatists and nonfiction writers from approximately 75 centers of PEN agreed to embark on a three-year global campaign to increase opportunities for displaced writers worldwide. Responding to the unprecedented flow of refugees, migrants, and displaced, all of which include writers and those whose stories need to be told, the 95-year old literary organization will undertake an initiative to put storytelling and literature at the center of an effort to heal and expand opportunities. Through its 145 centers, PEN will develop programs that will include residencies, workshops, mentoring, education and publications. The full scope of the campaign will be announced December 10, Human Rights Day.

Founded in 1921 out of the chaos and refugee flows after World War I, PEN anticipated and protested the suppression of freedom of expression in Nazi Germany prior to World War II and defended writers throughout Europe during the war, offering haven and setting up PEN centers in exile.

“PEN responds to the crises of our times,” said PEN International President Jennifer Clement. “We are writers. We believe in imagination.”

The 82nd Congress began with heartening and dispiriting news. Iranian-Canadian writer Homa Hoodfar was released from Iran’s Evin prison at the same time news arrived that Jordanian columnist Nahed Hattar had been gunned down outside court by a fundamentalist who claimed Nahed deserved to die for his ideas.

This pattern of good and terrible news also emerged in the past year with early releases of imprisoned writers in Tibet, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Vietnam, Qatar and Colombia at the same time the situation deteriorated with more arrests and killings in Bangladesh, China, Turkey, Ukraine and other countries….[cont]

October 30, 2017: Chatham House Rule and Other Civilities

Last week I participated in a number of forums operating under the Chatham House Rule—a large dinner in Washington with experts on Afghanistan, another in New York focused on the United Nations, panel discussions on North Korea, Myanmar, Ukraine and Iraq and a full-day meeting focused on troubled spots around the globe attended by former prime ministers, foreign ministers, ex-military officials and experts.

What struck me in this compressed tour of world conflicts was the civility and richness of the discussions which wrestled with problem-solving compared to the public discourse these days that sometimes seems reminiscent of a high school lunchroom.

In a meeting held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use information, but the identity and affiliation of the speakers are confidential. The purpose of the rule, first established in 1927 at Chatham House: The Royal Institute of International Affairs in London, is to encourage openness and the sharing of information. Anonymity is not to encourage personal gossip and rumor.

No problems were solved in last week’s meetings, but analysis from multiple points of view, which were not always in agreement, were debated and iterated. Issues, not personalities held the focus. To the extent personalities framed the problem, steps towards engagement or containment were set on the table.

No problems were solved in last week’s meetings, but analysis from multiple points of view, which were not always in agreement, were debated and iterated. Issues, not personalities held the focus. To the extent personalities framed the problem, steps towards engagement or containment were set on the table.

Throughout the discussions, I recalled Albert Einstein’s counsel: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking that created them.” It is a challenge to think outside traditional corridors of thought and even more challenging when respect for ideas is subsumed by attacks on people.

Many of today’s conflicts spring at least in part from the politics of identity—be that identity defined by religion, political party, gender, race or nationality. The aggregating principal of nations appears to be fragmenting in many areas of the world with authority breaking down or hardening into authoritarianism.

There never have been easy solutions for mankind living together, but the Chatham House Rule offers at least a momentary space for ideas to cross borders and barriers before being shot down.

October 19, 2018: London: Autumn Respite Around the Pond

A few years ago I penned a blog “Sounds of Summer” where I listened to the sounds of a summer afternoon. I let the politics and opinions and controversies of Washington, where I live, recede in my mind on the threshold of presidential elections, and I focused on the moments of nature and the wonders of a child’s summer world. I find myself wanting to retreat there more and more these days as the civic dialogue and political events seem harsher and less civil and downright mean.

In the last month I’ve had reason to travel to Beirut and London, where I considered events from a slightly different point of view, though no less fraught. The constant news coverage and the acrimony of the Kavanaugh Supreme Court hearings in the U.S. was replaced by the general uncertainty over refugees and the government in Beirut and by the angst over Brexit in London. While in Beirut, the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi broke in the news, and the horror of the unfolding tale of death and torture riveted attention in Washington and London as well. The possible political coverup currently brewing for this brutal violation of human rights remains the most troubling of all.

And yet for a moment—just an hour—in London yesterday I sat around the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens and allowed myself time to listen to the sounds and to witness life without a wider prism of consciousness and a larger world intruding.

On the crisp October morning the leaves stirred, still dusky green on the trees, not yet the vibrant reds and yellows of fall. Autumn arrived gently here in slight gusts of wind. A robust population of birds—elegant white long-necked swans, husky geese, green-faced mallards, plain brown ducks and a bevy of smaller birds cruised the water, circling the pond, eventually veering towards the edges where passersby tossed breadcrumbs and seeds. A troupe of white seagulls swooped in for a landing on the water like trained hydroplaners and then just as abruptly and deftly took off for other parts of London.

At the far end of the pond sat Kensington Palace, quiet that day, home to the Duke and Duchess of Sussex—Prince Harry and his American bride Meghan Markle—who at the moment were in Australia, where they announced they’re having a baby.

At the far end of the pond sat Kensington Palace, quiet that day, home to the Duke and Duchess of Sussex—Prince Harry and his American bride Meghan Markle—who at the moment were in Australia, where they announced they’re having a baby.

People of all backgrounds circled the pond, dressed in slacks, jeans, dresses, light jackets, in hejabs and thwabs, children in strollers, young and old, sitting on the benches that ring the pond. School children in florescent green and yellow vests jogged by on a morning run.

Two elderly ladies and I increased our walking pace in a silent, unannounced race to the one empty bench at the bottom of the pond. I won, but they sat down beside me anyway, and we shared this coveted space where they talked quietly, and I wrote, and we watched this slice of morning.

A tiny dog trotted by as two stragglers panted past trying to catch up with their schoolmates. A couple stopped beside us and talked loudly on the phone in a language I didn’t recognize. In front of us a swan groomed herself, shaking off the water.

The grim headlines in the news: the possible failure of Brexit, the assassination and dismemberment of Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate, the US government’s closing of borders to a new convoy of migrants, the slippery commitment to truth for a moment receded on a blue sky London morning on the edge of autumn before the days grew short and dark.

A teacher with his final two lagging students jogged past, shouting, “Come on, guys…Let’s sprint to the finish! You can do this!”

Reluctantly I rose from the bench and left my fellow sojourners as I headed into the city for meetings and the work of the day.

October 2019: [Beginning in May 2019 I started writing a retrospective of work with PEN International for its Centenary so posts were more frequent in 2019-2020. In October 2019 there were two posts in the PEN Journeys and in October 2020 there were four.]

October 9, 2019: PEN Journey 10: WiPC: Beware of Principles

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

In the summer of 1993 before taking over the Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee I studied hundreds of individual cases on PEN’s list of over 900 cases which was published twice a year. I studied the regions of the world where conflict was rife, where governments were most oppressive and where writers were most threatened. I also used the time to conceive three long term projects because I knew when the job began, there would be less time for long term thinking.

First, I hoped we could gather the many poems and stories from imprisoned writers over the years and get these published into a book. In studying the cases, I came to understand that those who survived harrowing experiences were often those able to keep their imaginations alive and if possible were able to write. “We lived in Paris in our minds,” one prisoner in dire conditions inside the Western Sahara recounted. A book of these writings would celebrate and inspire and could also be used by PEN centers in their work.

Second, I wanted to convene the Writers in Prison Committees from around the world in a conference to strategize our work. PEN’s other standing committees had such meetings outside of the congresses, but WiPC never had. The PEN congresses were often filled with competing programs and those working on WiPC issues were not always the delegates. We needed to gather and plan together for several days.

Finally, I hoped to expand the roster of Writers in Prison Committees in the PEN Centers so that we could increase the number of members working and the number of writers on whose behalf we worked.

WiPC Coordinator Sara Whyatt and researcher Mandy Garner and I agreed on each of these goals. Every two weeks we met in the large airy WiPC office at the top of the Charterhouse Buildings in London or often at the tea shop across the alley. At the end of our strategy sessions we would discuss how to move forward the longer range goals. I learned an important lesson—first, a goal begins with an idea then is realized by having talented, committed people around. For me that began with Sara and Mandy, who set steps in motion. And then each project found a path forward as people arrived into our circle to help accomplish the tasks….[cont]

October 25, 2019: PEN Journey 11: Death and Its Threat: the Ultimate Censor

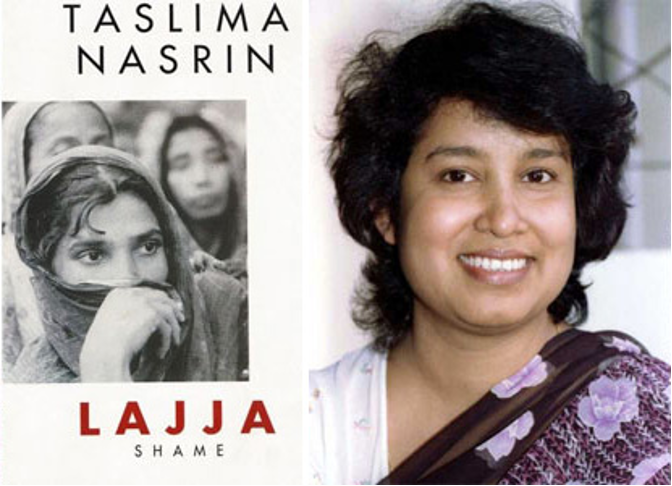

In Bangladesh novelist Taslima Nasrin was in hiding. Death threats had been issued, a price put on her life. On the streets of Dhaka and other cities, crowds threatened to hang her because of her words in a newspaper challenging the Koran and Islamic laws and because of her novel Lajja (Shame) which depicted Muslim atrocities on Hindus after a mosque’s destruction in Ayodhya, India.

The time was summer 1994. In London Sara Whyatt, PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee Coordinator, and I sat in a Kensington hotel restaurant waiting to meet a man who’d called the office and said he was Taslima’s brother and wanted to talk with us. PEN had been actively working on Taslima’s case for the past year, sending out Rapid Action Alerts, meeting with Bangladeshi government officials in London and in the U.S. and Europe, calling on the government to protect her. The case had gained international attention. Given recent violence around fatwas, including those on Salman Rushdie, we were wary. We didn’t know Taslima had a brother. We spoke with MI5 who advised us to have a spotter for the meeting. We arranged a tell so that if the encounter was not legitimate or we perceived trouble, I would take my sunglasses from the top of my head and set them on the table. The spotter—PEN’s bookkeeper—sat at another table and could quickly summon help. We weren’t certain, but we thought MI5 was also in the hotel.

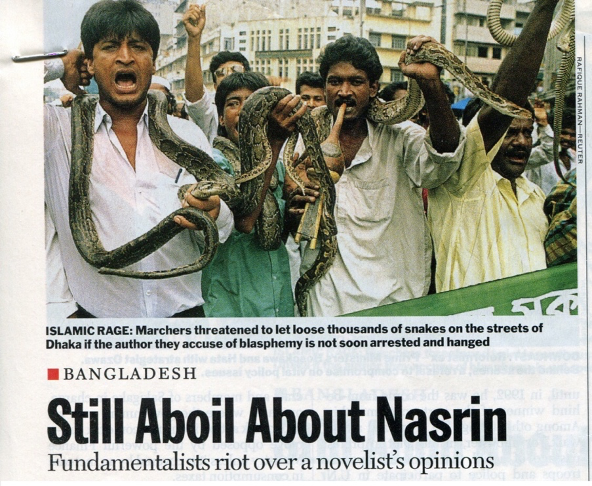

In retrospect the drama around Taslima’s case seems inflated, but during that period of 1993-1994 the situation had escalated to the point that religious leaders were warning that the government would be overthrown if Nasrin was not arrested. In June 1994 when an arrest warrant was issued, Taslima went into hiding. A nationwide hunt was launched, and snake charmers carrying poisonous snakes marched in Dhaka and warned that thousands of snakes would be let loose if Nasrin was not arrested by June 30.

Time, July 11, 1994. Photo by Rafique Rahman-Reuters

In this atmosphere PEN had received the call from Taslima’s older brother. International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and PEN’s Women’s Committee, in particular its chair Meredith Tax in New York, had been in touch with Taslima and her lawyers, but in the time of faxes, (now fading), inconsistent telephone connections, and no internet between writers, no one had yet confirmed a brother coming through London. This kind of high drama was not PEN’s usual modus operandi. In the years I chaired PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), more than 900 writers threatened, detained, in prison, and killed came across PEN’s desk annually. Approximately a quarter of these were designated main cases which meant PEN had sufficient information to verify the situations and had members to work on the writer’s behalf. However, only a few became global causes like Taslima’s, gathering energy, attention and advocates around the world. This usually happened when the threat of death was credible and immanent and when the circumstances of the writer connected to larger issues.

That day in London, a man in his thirties approached our table. He looked so much like pictures of Taslima that we quickly set aside our suspicions. He worked for an airline and was passing through London. He was able to answer questions and confirm details of the case such as what Taslima had actually said to the newspaper which had misquoted her calling for revision of the Koran. I still have my notes from that meeting. Her brother explained that Taslima had said she wanted to modify Sharia laws, not the Koran. “I want men and women to be equal,” she’d said. She was charged with blasphemy under a law left on the books by the British.

Her brother told us that her lawyer was afraid. The lawyer couldn’t move for bail unless Taslima was present, but if the government didn’t give security for her, they couldn’t take the risk of Taslima coming to court. The government said if Nasrin went to court, anything could happen in court or in jail. In jail she could be killed. Her father’s home had been attacked, and he was now under protection.

Her brother confirmed that Taslima had finally agreed that she needed to leave Bangladesh though she was reluctant. “If I go from Bangladesh, who can write about these poor women?” she asked. And yet she wasn’t able to write anything now, he said, and her life was not safe if she stayed.

Her trial date had been set for Aug. 4. If she didn’t appear, the government would seize her things, including her passport, which they had taken away before but had returned when she resigned her post as a doctor. She was a medical doctor as well as writer.

Her brother’s message to us that day was: “Save my sister!”…[cont]

October 5, 2020: PEN Journey 44: World Journey Beginning at Home

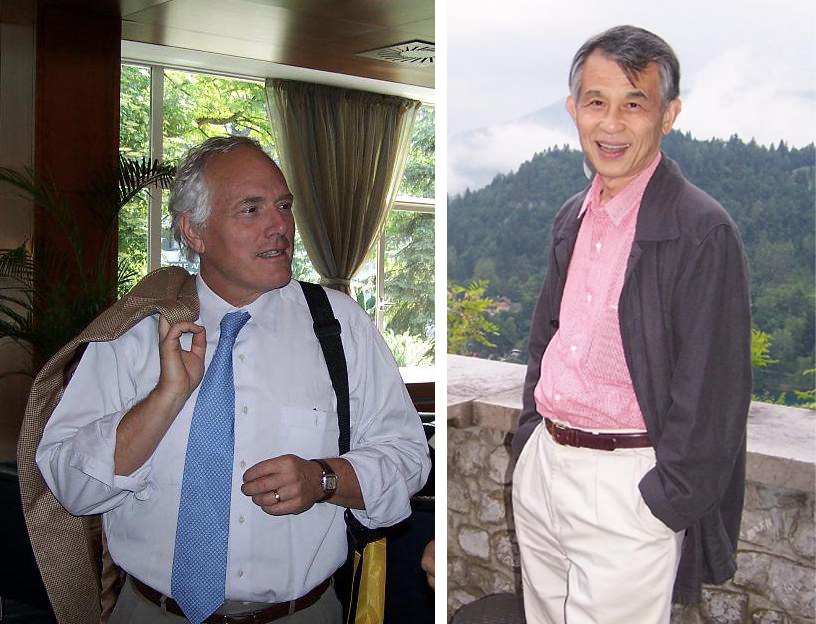

After PEN’s Asia and Pacific Regional meeting in Hong Kong February 2007, I flew to Tokyo for a two-day visit with members of Japanese PEN, along with International PEN board members Eric Lax and Takeaki Hori. We met with Japan PEN’s board, and in the evening I shared a stage and conversation with Mr. Hisashi Inoue, chairman of Japan PEN and one of the country’s well-known playwrights. Part of our discussions explored the possibility of Japanese PEN hosting an International PEN Congress. Only once before, in 1984, was the World Congress held in Japan.

International PEN Board members Eric Lax and Takeaki Hori

Housed in an impressive building in Tokyo, Japan PEN was one of International PEN’s largest and most active centers with one of the more interesting histories. Founded in November 1935 on the eve of a tumultuous period in world affairs, Japan PEN members committed to the PEN ideals of freedom of expression and “one humanity living in peace in one world.” By 1935 Japan had left the League of Nations in the wake of the Manchurian Incident and was moving towards international isolation, a direction that concerned liberal literary figures and diplomats. In this climate International PEN in London, with support from leading novelists, poets and foreign literary figures, reached out and requested that writers in Japan form a PEN Club. Japan’s well-known novelist Toson Shimazaki served as the founding president. As suppression of free speech increased as war in the Pacific broke out and the Second World War advanced, Japanese PEN stayed in limited contact with International PEN in London and provided a unique portal to the world for its writers and citizens during that time.

Japan PEN members at PEN’s 71st Congress in Bled: Furukawa Taeko, Miyakawa Keiko and Yonehara Mari, along with Fawzia Assad (Suisse Romand PEN) Huguette de Broqueville (French PEN) and Celia Balcazar (Colombian PEN) and Takeaki Hori (PEN International Board & Japan PEN)

Personally, I remember the hospitality of Japan PEN members who took me out on the Ginza to toast my birthday as I rounded a decade. I had explained that I needed to fly home that evening, a day early to share the birthday. I still remember the glasses of pink champagne flowing up and down the Ginza, (though I was drinking sparkling water), as my own new decade was heralded, then flying halfway around the world and arriving in time to have another dinner that same night with my husband.

Three years later, in September 2010 Japan PEN hosted the 76th PEN International World Congress in Tokyo, one of PEN’s largest with representatives from 90 centers around the theme “The Environment and Literature—What Can Words Do?”

******

World War II, D-Day, the fall of the Berlin Wall—all were global events in the 20th Century which framed the history that followed for much of the world and stirred both despair and optimism among politicians and citizens and inspired stories and poetry among writers. PEN’s Peace Committee conference in March 2007 settled on three themes: Languages under Threat—Dying Cultures, Reading as a Social Event, and Post-Totalitarian Resistance.

Bled, Slovenia, setting of PEN International Peace Committee meeting, March 2007

In my files I found the keynote paper “Post-Totalitarian Resistance” by Peace Committee Chair Edvard Kovač, a portion of which I quote here. It provokes thought with the kind of open-ended questions that don’t necessarily have answers but can lead to discovery. Contents of PEN’s forums are among its important legacy….[cont]

October 13, 2020: PEN Journey 45: Dakar, Senegal: The Word, the World and Human Values

PEN International’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal July 2007 celebrated the first Pan African PEN Congress with over 200 writers gathered from over 70 countries around the theme “The Word, the World, and Human Values.” The theme had been developed by PEN’s African centers who assisted in the planning of the Congress which brought together writers from every continent as well as from across Africa.

Program for PEN International’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal, July 2007

The setting was grand on the rugged Atlantic coast at Le Meridien Hotel. Government luminaries, including the President of Senegal Abdoulaye Wade and Prime Minister Cheikh Hadjibou Soumaré greeted delegates at the opening and closing ceremonies in the tiered auditorium where the Assembly of Delegates conducted PEN’s business. Ministers of Culture, Information and Foreign Affairs hosted dinners in the evening as did the President and Prime Minister.

Because PEN monitored the human rights situation in countries, particularly regarding freedom of expression, PEN vetted carefully countries where it held its Congresses. Senegal had prosecuted four journalists the past year, but none were in detention, and PEN Senegal and the International Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) were advocating to abolish defamation laws used to repress writers across the continent. Senegal in general was an open society for writers. On the few occasions when PEN hosted Congresses in countries with more repressive regimes, it took no assistance from the government and used the occasion to advocate on behalf of the writers.

The 73rd Congress marked the end of my term as PEN International Secretary. At my first Congress as International Secretary, I’d opened with the image of a bridge soaring into the sky, a bridge that had taken decades to construct. I had suggested that for the last decade International PEN had been building an organizational bridge into the 21st century. Having occupied the position of International Secretary for three years on a daily basis, I could attest that PEN was a robust, though occasionally fragile, organization whose bridges across cultures were real, whose joints were welded by the principles of the PEN Charter and by the fellowship among writers.

For me, memories abounded—memories of the ancient city of Diyarbakir, Turkey where Kurdish and Turkish writers translated each other side by side for the first time; the gathering in Hong Kong where writers from mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and the diaspora, along with other writers from around the world, met and shared ideas and literature; and the memory of the dungeons of Gorée Island with its dark doorway to the Atlantic, similar to “the door of no return” on Ghana’s Cape (Gold) Coast where the most basic human rights had been violated centuries before when men and women were shipped as slaves to other countries, including to my own.

At the Congress PEN members traveled to Gorée Island off the coast of Dakar to see and to pay homage to this history and through PEN’s work to act on behalf of freedom and human dignity today.

Visit to Gorée Island, Senegal. L to R: Carles Torner (Catalan PEN), Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN), Lucian Kathmann (San Miguel PEN), Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Mamadou Tangara (Gambia.)

A Nobel Laureate in science once said, “Discovery consists in seeing what everyone else has seen and thinking what no one else has thought.” That could be said of the writer whose imagination saw bridges between people and cultures where others saw clashes and conflict.

Before each Congress I made a point of reading histories of PEN, particularly the history of the place where PEN was holding its Congress. The 73rd Congress was only the second time PEN’s whole international body had met in Africa. Forty years before a PEN delegate at the 35th Congress in Abidjan, Ivory Coast recalled ascending the stairs of the Congressional Hall between a double row of guards dressed in scarlet and gold with raised sabers. At that Congress PEN members took special notice of writers in prison in Communist and noncommunist countries. There were not many PEN centers in Africa then, but PEN Senegal existed. At the Congress the prior year in New York City in 1966, delegates from the Ivory Coast and Senegal had attended as had observers from Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria. By 2007 PEN had 15 centers in Africa, including in those countries whose writers had visited the New York Congress. Today PEN has 28 African centers….[cont]

October 20, 2020: PEN Journey 46: Wrapping Up

I finished my term as International Secretary of PEN July 2007 at PEN’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal. I handed over the responsibility to my longtime colleague Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) who would continue to work with the Board, the Executive Director Caroline McCormick, new Treasurer Eric Lax and President Jiří Gruša. We had executed many changes in the last three years, and those who had been involved were continuing and active both in the international leadership and in the PEN centers.

Before the Congress, the staff and PEN members gave me a farewell party at PEN International’s relatively new London headquarters on High Holborn. PEN is about people, and I’d been fortunate to work over many decades with dozens of talented writers who were also competent in organizational work, friends from around the globe who remain friends today.

PEN International Farewell gathering in London 2007 with friends and staff, including Caroline McCormick, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Jane Spender, Sara Whyatt, Moris Farhi, Peter Firkin, Eugene Schoulgin, Frank Geary, Emily Bromfield, Mitch Albert, Mandy Garner.

As a Vice President, I would continue to work, write appeal letters to governments for the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC)’s RAN (Rapid Action Network) cases, speak when asked and hold meetings in Washington when asked, but I could return to being a writer. American PEN’s Executive Director Michael Roberts asked me to join American PEN’s board. I demurred and said I needed a break, but he and others urged me so in 2008 I joined the board of PEN America but worked at a far less intense pace for the next six years. When American PEN’s new Executive Director Suzanne Nossel came on, I was asked to extend for an additional year as a Vice President while she oriented to PEN’s international work. It is difficult to step away from PEN though most who are engaged find they must for a time, though not too far away.

As I left the historic Senegal Congress that July 2007, I boarded a plane and flew out over the Atlantic to Italy where I met up with my husband by a lake in one of our favorite spots for a vacation. He had patiently waited those three years as I spent 10-15 days a month on the road. In the first week without PEN’s emails and phone calls and conferences, we talked; I wrote, and I read four books in six days.

Back home I soon realized I needed to join the 21st century as a writer. At PEN we had begun to use some tools of social media in publicizing cases of writers under threat, but I hadn’t engaged personally. I remember sitting with a group of women writers in Washington, DC, many younger than me, who were talking about their websites and blogs and Twitter, and Facebook. In 2007 writers having URLs, Twitter handles, Facebook pages was relatively new. Twitter had only launched the year before, and though blogs had been around for a few years, I had never written one. Facebook seemed an odd medium, also only a few years old. I was of the “private” generation; we were not prone to sharing our activities and feelings on a “social” platform. Those of us who’d been journalists were used to having to condense stories, but never to 140 characters which Twitter demanded. We were in a new communications age, and I needed to understand and at least to put a toe in the water, even if I didn’t jump fully in.

Encouraged by friends and agent, I set up a website. The developer urged me to blog. I didn’t want to blog, I explained. I wanted to write fiction and occasional journalism, but I agreed to post a blog once a month. I have done so for over ten years now. Often when I considered what was worth writing about each month, I found myself reflecting on work with PEN. When asked to write about PEN’s history as I’d witnessed it in anticipation of the Centennial, I reasoned I could post twice a month. That seemed a reasonable way to get through PEN’s history year by year. A serial blog. I have sped up the pace since Covid locked us all into our homes and travel has halted. I have now come to an end of this particular PEN Journey though I will write an introduction. I will also reference links to those blog posts I wrote after 2007 when I continued to work with PEN.

In this final post, I want to review a few areas of PEN International I feel I haven’t explored sufficiently, and I want to give a quick view forward of what and who came next….[cont]

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and was asked by PEN International to write down memories. I have done so in 46 PEN Journeys and have been asked to write an introduction to these. Below is the introduction coming last, drawn in part from an earlier blog post of the same title, but not in this PEN Journey sequence.

“In a world where independent voices are increasingly stifled, PEN is not a luxury. It is a necessity.”—Novelist & poet Margaret Atwood, former President of PEN Canada

“…freedom of speech is no mere abstraction. Writers and journalists, who insist upon this freedom, and see in it the world’s best weapon against tyranny and corruption, know also that it is a freedom which must constantly be defended, or it will be lost.”—Novelist Salman Rushdie, PEN member

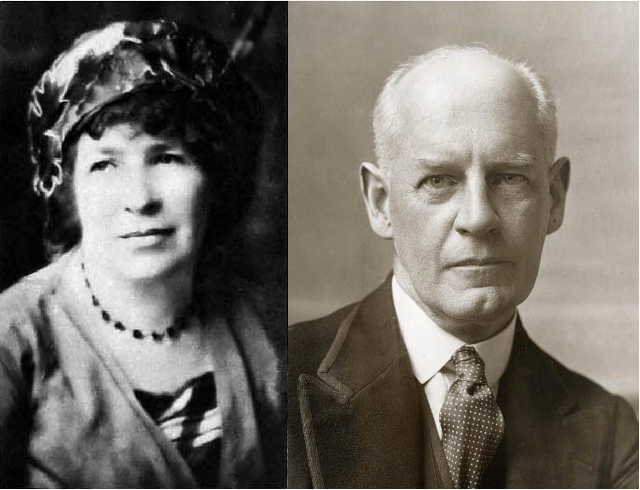

PEN International was started modestly 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catharine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others, conceived if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, they reasoned, at least among writers of Europe.

PEN Founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and first PEN President John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN [Poets, Essayists & Novelists—later expanding to Poets, Playwrights, Essayists, Editors and Novelists and now including a wide array of Nonfiction writers and Journalists] spread quickly. Clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, and the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. A decade later when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, he donated the prize money to International PEN. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace. Galsworthy spoke about the possibilities of a “League of Nations for Men and Women of Letters.”

Members of PEN began to gather at least once a year in 1923 with 11 Centers attending the first meeting. During the 1920’s writers regardless of nationality, culture, language or political opinion came together. As the political temperature rose in Europe, PEN insisted it was an apolitical organization though its role in the politics of nations was soon to be tested and ultimately landed not on a partisan or ideological platform but on a platform of ideals and principles.

At a tumultuous gathering at PEN’s 4th Congress in Berlin in 1926, tensions rose among the assembled writers, and the debate flared over the political versus non-political nature of PEN. Young German writers, including Bertolt Brecht, told Galsworthy that the German PEN Club didn’t represent the true face of German literature and argued that PEN could not ignore politics. Ernst Toller, a Jewish-German playwright, insisted PEN must take a stand.

After the Congress Galsworthy returned to London and holed up in the drawing room of PEN’s founder Catharine Scott where he worked on a formal statement to “serve as a touchstone of PEN action.” This statement included what became the first three articles of the PEN Charter. At the 1927 PEN Congress in Brussels, the document was approved and remains part of PEN’s Charter today, including the idea that “Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.” The third article of the Charter notes that PEN members “should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people and dispel all hatreds and champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

As the voices of National Socialism rose in Germany, PEN’s determination to remain apolitical was challenged though the determination to defend freedom of expression united most members. At the 1932 Congress in Budapest the Assembly of Delegates sent an appeal to all governments concerning religious and political prisoners, and Galsworthy issued a five-point statement, a document that would evolve into the fourth article of PEN’s Charter.

When Galsworthy died in January 1933, H.G. Wells took over as International PEN President. It was a time in which the Nazi Party in Germany was burning in bonfires thousands of books they deemed “impure” and hostile to their ideology. At PEN’s 1933 Congress in Dubrovnik, H.G. Wells and the PEN Assembly launched a campaign against the burning of books by the Nazis and voted to reaffirm the Galsworthy resolution. German PEN, which had failed to protest the book burnings, attended the Congress and tried to keep Ernst Toller, a Jew, from speaking. Some members supported German PEN, but the overwhelming majority reaffirmed the principles they had just voted on the previous day. The German delegation walked out of the Congress and out of PEN and didn’t return until after World War II. Their membership was rescinded. “If German PEN has been reconstructed in accordance with nationalistic ideas, it must be expelled,” the PEN statement read. During World War II PEN continued to defend the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. (Today German PEN is one of PEN’s active centers, especially on issues of freedom of expression and assistance to exiled writers.)…[cont]

My view of fall has changed. I used to see it as a bit of a downer. Now I see the bright colors as symbols of lessons learned and old beliefs dropping away and making way for higher thoughts and ideas.

I love that perspective. It does open up possibilities and sweetens the bittersweet feel of this time of year. And thank you for the stunning picture in this blog!

Fascinating, as always, Joanne. I can’t wait for your book.

I am trying to think what October looks like down under, heading towards summer, I guess.

Thank you Joanne. I much enjoyed reading your October blog—amusing but also serious.

Glad you mentioned Nazim Hekmat, I always enjoyed reading him. Very much liked the Tolstoy part.

Look forward to the next blog.

Yes, Hikmet’s image of a yellow geranium in a tin can I have carried with me and often think of as an image of hope in some desperate prison situations for writers on the front lines of freedom of expression.