Dinner and a Movie or Frontlines with ISIS?

(I drafted the blog post below March 12, 2019, but I was concerned that even this brief exchange might put my friend in danger so I checked with her before I published. She asked that I not publish it while the conflict was going on, so I filed the post away in the draft file on my website. At the time the situation on the ground in Syria was precarious. I recently re-discovered this file two and a half years later. My thesis still holds even while the circumstances on the ground have changed. It is now safe to publish this, though it is still problematic in situ.)

JLA text: “If you’re in town, you want to grab dinner…and movie tonight?” —8:53 am

Friend text: “Hi from Syria where I’m covering final battle with ISIS…” —9:39 am

I began my writing career as a journalist decades ago with fellow young women reporters figuring a way to get out and report on the world.

I eventually struck out on a different path, went back to graduate school, focused on fiction, married, raised a family, but these women stayed on course and are still reporting from the frontlines and are still some of my close friends.

Added to the above exchange that morning was an email from another friend from those days who told me she’d just won the Overseas Press Award for best commentary in any medium on international news.

All of us have circled the globe—they as reporters, me as novelist and worker with organizations on the front lines of human rights, education and conflict. I’m proud of these friends and feeling nostalgic. I often end my correspondence by the salutation: “Stay safe.”

These days many women work on the frontlines of conflict as journalists and correspondents, but this wasn’t always the norm. Means and methods of reporting have also changed. The pace of news and the speed with which it is reported has increased dramatically over the last half century even as the number of organizations supporting correspondents in foreign lands has diminished for women and men. More and more news is derivative, sourced from a few well-staffed newspapers and media outlets then riffed on, commented on, regurgitated by pundits around the globe. There is more talk than ever, 24-hour talk, but those inhabiting the front lines—women and men—who witness for the rest of us and send back clear, factual perspectives are a necessary, yet possibly threatened species. With the development of the internet, however, there are now networks of international reporters such as those who collaborated on the Panama and Pandora papers and the network the International Center for Journalists—ICFJ—nurtures. ICFJ’s motto “It Takes A Journalist” rings truer than ever.

“Stay Safe,” I wrote back to my friend. “Let’s hope there’s a movie we want to see when you get home.”

(As I have the past eight months, I’m also including here a retrospective of the month over the last 13 years of this blog. I’m starting to move about again, though have yet to travel abroad and so offer this space as an armchair view of the world when we were face to face with posts from India, Sierra Leone, Gibraltar, Qatar, Czechoslovakia, Switzerland, and the United States. Because the month is November, it is Thanksgiving in the U.S., and many posts focus on that custom of giving thanks. For many Americans, myself included, Thanksgiving is a favorite holiday. It includes family and friends who gather not in religious ceremony but in a universal ritual of giving gratitude.)

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

November 27, 2008: The Power of Thanks

I’m up early on Thanksgiving morning before the house awakes. It is still dark outside. Our dogs—Max, a German shepherd, and Nala, a golden retriever—look up at me to see if it is really time to start the day. They know the routine. Max follows me downstairs to go outside to get the morning papers—The Washington Post dropped near the porch, The New York Times left on the sidewalk, then a trip to the kitchen to pick up dog bones before we return upstairs where I get on an exercise bike to read the papers and the dogs settle on the floor beside me to chew their bones.

But this morning I’m up too early; the papers have not yet arrived. The house, which will fill with people in a few hours for Thanksgiving dinner, is still sleeping. I love this stolen time and curl up on the sofa by the fire with a pad of paper.

This American holiday, set aside for the purpose of giving thanks, is rooted in the nation’s earliest history. It celebrates the time when the indigenous Indian population shared food with the newly arrived European settlers during their first brutal winter. Unfortunately the subsequent history between the Europeans and the Indians was not so benign, but it is this original encounter that we commemorate.

This year seems an especially important time to give thanks. When citizens in the U.S. and in countries around the world are staggered by financial downturns and fear the road ahead, it is helpful to remember the words of President Franklin D. Roosevelt who took on the U.S Presidency in the midst of the Depression in the 1930’s.

In his first Inaugural Address in 1933 Roosevelt said:

So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself….In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory…

In such a spirit on my part and on yours we face our common difficulties. They concern, thank God, only material things….Yet our distress comes from no failure of substance. We are stricken by no plague of locusts. Compared with the perils which our forefathers conquered because they believed and were not afraid, we have still much to be thankful for. Nature still offers her bounty and human efforts have multiplied it. Plenty is at our doorstep, but a generous use of it languishes in the very sight of the supply.

There is no more powerful antidote to fear than gratitude. Acknowledging the blessings at hand, especially the non-material blessings such as family, friendship and community, breaks the hold of depressive thought. The expected call to service by the incoming Obama administration is potentially as potent a rescue of national purpose and consciousness as the financial plans unfolding.

The good news is that the antidote of gratitude and service is already at hand. We don’t need the approval of Congress or an upturn in economic conditions to undertake them.

Outside now the sky is growing light. I hear the newspaper drop by the front porch. Happy Thanksgiving!

November 29, 2009: Two Delhi Stories: Going to the Movies and Elephants Are Forever

Going to the Movies

Sitting on a thin gray-pink mat on the train platform, the children are waiting for us. We make our way over stones and past garbage, through a chain-link fence to what looks like an abandoned station. Along the tracks shanty houses and rows of laundry line the route a few feet from where the trains will come whizzing by. Some of the children, ages 5-15, live here, but most don’t have homes. They are the street children of Delhi, India, a population estimated between 150,000 to one million in Delhi alone. Some have grown up in the city and left their homes but more have stowed away on trains and arrived from the countryside or other cities looking for their future.

We are visiting Salaam Baalak [Salute the Children] Trust which works with these children to help return them to their families if that’s possible. But if the children have been abused or the parents have sold them to traffickers, they are not returned. In that case training, schooling and places to live are sought.

Our guide is a teenager who himself had lived on the street but for whom intervention made the difference. He notes that for most children, the street will prevail. He explains that 300 trains come into Delhi every day at different stations, and the children slide off of these. If they aren’t found within a few weeks, it is difficult ever to get them back for they may be trafficked for labor or prostitution or petty thievery or just become denizens of the streets.

“We go to the train stations and look for the new children,” he says. “We can recognize the new ones; they are looking for help; they don’t know anyone. Kids living on the street learn how to survive, but anyone on the street for a few weeks starts to enjoy the freedom not knowing what may yet be in store.”

Many of the children hide at the stations, waiting for the luxury trains to come through. While the train is stopped, they scurry into the cars to gather the discarded magazines and food which they later sell.

“What do you think they do with the money they get?” our guide asks.

“Buy food?” someone suggests.

“Yes.”

“Buy drugs?”

“Usually glue to sniff, yes. But the largest amount of their money goes to films.”

“Films?” we ask.

“The cinema. On Fridays when the new films come out, the children wash, clean their clothes and go to the movies!”

For a few hours a week the children soar away in their imaginations and exist somewhere else. The question hovers how to feed and nourish these minds so they can in fact someday soar away and live somewhere else.

Elephants Are Forever

In the middle of one of Delhi’s larger slums the Katha Khazana School serves the community from infants to parents and focuses on pre-school through level 12. The school is for children of the most impoverished; many are rag pickers who search through the city’s dumps with their parents for items to use or sell.

Children enter the brightly colored arched gateway of the Katha Khazana School into a sprawling open spaced building with courtyards and arched doorways, decorated with startlingly original art—brightly colored and friendly snakes, dragons, lions, tigers, fish–all swimming, prancing, hanging on the walls. At the end of one corridor a round-faced elephant with big pink ears and a trunk extended into the hall greets the visitors. The art is by the children and is added to and replaced every quarter when the theme of study changes. This year’s theme, through which the curriculum of language, social studies, civics, math, science, art, etc. is focused is Sustainable Environment, and the particular focus this quarter is: Elephants Are Forever!

My guide Sadik started six years ago at the Katha school and now at age 18 is about to graduate and hopes to go on to college. He also works with Katha, which has 50 early childhood centers and 96 primary schools, publishes children’s books and works with women on small income generating businesses in sewing, cooking, and teaching. In the past years, the women have earned hundreds of millions of rupees in their projects and have been able to lift their families out of poverty.

“Katha started with a few children in 1988,” said Geeta Dharmarajan, executive director. “We soon realized we couldn’t change the way the slums look, but we could bring people out of them. We hope to educate the children to be leaders in their communities.”

Today Katha helps children and their mothers in 72 slums and street communities across Delhi. It is just one of many organizations working in the communities in Delhi with staff and volunteers to facilitate the transition from the street by changing first the landscape of the mind.

November 29, 2010: Sierra Leone: After the Eclipse

“Why does a rainbow appear in the sky?”

“What is an eclipse?”

“Why are there crop failures?”

“What are these called in Mende?”

“What do our elders think are the reasons?”

“How does science explain them?”

I am sitting in the back of a science class in a junior secondary school in a village hours outside of the nearest city Kenema, in the mining district of Sierra Leone, an area devastated by ten years of civil war in the 1990’s. To get here we have driven hours down red dirt roads filled with potholes where the rains have beaten the earth. The countryside is lush with palm trees, banana trees, rice paddies, grasses of all sorts, including large waving elephant grass.

The students—boys and girls in green and white uniforms—sit on wooden benches in front of wood desks and are taking notes in small notebooks. At the front of the classroom is a pot of water and a cup for students who are thirsty; this is not the case in many schools, and a luxury. What is also notable in this classroom is the skill of the teacher and the enthusiastic participation of the students when the teacher, a young man in slacks and short sleeve shirt, asks questions. One girl in particular waves her hand to answer each question.

The teacher solicits answers and discussion, asking students to consider the traditional beliefs for each of these phenomena, then he explores science’s explanation. He talks in English and Mende, the local language. An eclipse? The traditional belief in their villages is that the chief or someone important is about to die and that the spirit in space is swallowing men. He then asks a student what happens if a torch (flashlight) is shined in his face and someone puts a book between him and the flashlight. The teacher draws on the blackboard a picture of the sun, the moon and the earth and continues with an explanation of their orbits. There are no books in the classroom and few props.

“Is that not so?” he asks from time to time. At the end of the lesson, he asks the students which explanation they believe. They all agree with the scientific explanation.

The skill of this teacher is unusual, but what is not unusual is that this young man in his early twenties is a volunteer teacher, not yet credentialed and not paid. He is one of 11 male teachers–there are no female teachers–at the school. All are volunteers, yet to be credentialed, though six are taking a distance education course to become certified. Only the principal is a certified teacher. He gave up a more prestigious job when the village asked him to come head this school. The school sent its first group of students to take the national exams this past year and came away with strong results.

Schools in this eastern region of the country on the road to Liberia were particularly devastated during the civil war. This is a mining community, and the miners have also contributed their own funds to the chiefdom to help the school as has the International Rescue Committee, my host. In 2006 the government built this junior secondary school (equivalent of grades 7-9), but the school has still not been officially approved in part because of the shortage of qualified teachers.

During the war (1991-2000) over a thousand schools were destroyed in Sierra Leone; many were closed for ten years. Hundreds of thousands of people were displaced. But now villagers have come back to their villages, and the government has rebuilt and built anew schools all over the country. The government says there are now one million children in primary school, out of a population of 6.5 million people. But there is a large shortage of teachers, especially of trained teachers. At least 40% of the current teachers are said to be volunteer. These young men and fewer women teach for no salary, but with the hope of getting credentials and eventually pay. The government has committed 18% of its budget to education and set forth a new education policy which includes teacher training. But the pace is slow.

After the visit to the junior secondary school, we go to visit the primary schools which feed into this school. Both schools we visit were destroyed during the war. At the first, the education coordinator with us recognizes the principal, who worked with him in the schools in the refugee camps in Guinea during the war. A number of the senior educators in the region got their experience in these refugee camps.

As we cross a log bridge over a stream to visit the next school, our vehicle gets stuck on a broken log on the bridge. Beside the stream, women are washing their clothes. We climb out of the car and jump onto the land and continue the journey on foot through the bush, avoiding giant red ants marching along the ground beside us.

The second primary school was originally a missionary school built in 1924, but burned down during the war and now rebuilt as a government school.

All over this beautiful lush country which has the world’s third largest natural harbor, a stunning coastline that could rival Monaco or Cannes, a country with diamond, gold and mineral wealth, the devastation of war remains, side by side with the determination of citizens, including many from the diaspora who have returned, to build back their country, starting with the education of its children, for education of the next generation is what can bring Sierra Leone, currently ranked the third-lowest on the Human Development Index and eighth lowest on the Human Poverty Index, out of an eclipse that lasted over a decade and into its future.

November 30, 2011: Tunnel of History

I’m at the bottom of a cave inside a rock riddled with tunnels dug over the centuries, including during World War II when Allied Forces excavated miles of tunnels to protect themselves and their ammunition from enemy forces.

At the bottom of this cave is the legendary home of the Gates of Hades–the Underworld–in Greek literature. This area was considered the end of the known world. It is the juncture where Hercules crashed through the Isthmus as he tracked across the Atlas Mountains to complete one of his last labors. In his impatience he pulled apart the land mass between Gibraltar and Tangiers, creating the Strait where the Atlantic and the Mediterranean now meet and creating the separate continents of Europe and Africa.

This geological feat was a side effect of Hercules’ labors to rid the ancient world of monsters. Legend has it that Hercules used the Rock of Gibraltar and a small mountain in Spanish Morocco as hand holds; these are now designated as “The Pillars of Hercules.”

On the rocks Hercules wrote: “Non Plus Ultra”— “There is nothing beyond” as a warning to sailors lest they go further at their peril. When Columbus “discovered” America, the Spanish amended their Royal Coat of Arms to read “Plus Ultra” –to indicate there was something beyond.

Myth merges with history and imagination as I sit at the bottom of this cave in my imagination and contemplate the stirring of the continent above and the continent across the strait and the one across the Atlantic. What monsters might Hercules take on today and what creative solutions might he crash through to find?

(Imaginative responses welcome. Happy Holidays!)

November 2012: No blog posted

November 1, 2013: Qatar: A Poet in a Desert Cell

(This piece also appears on GlobalPost.)

DOHA, QATAR — We stood outside the guard house in the desert wind on the outskirts of the city. Doha Central Prison rose on the horizon of a barren, rock-strewn landscape, electric wires cutting across a cloudless sky. We had been told we had permission to visit Qatari poet Mohammed al-Ajami, whose 15-year sentence for two poems had been confirmed the previous day by the high court.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

For five hours we stood, paced, sat in broken chairs, negotiating on mobile phones with the Attorney General’s office. The prison authorities had not received the request for our visit. The guards changed twice while we waited, guards from different nationalities as are most of the workers in Qatar. They were friendly, shared fresh oranges with us as the hours passed, but had no authority to help.

Inside the prison members of al-Ajami’s family were visiting him and knew we were out there. Al-Ajami knew we were there and wanted to see us. No one had gotten this far, the family later told us. But in the end we were denied.

For the last two years Mohammed al-Ajami has been in solitary confinement with limited access to visitors. A known poet in the Gulf and the father of four, al-Ajami was a literature student at Cairo University in 2010 when he recited a poem in his apartment among friends, a poem that allegedly criticized the Emir. The poem was in response to a poem by a fellow poet, but one of the students in the apartment recorded al-Ajami and uploaded the reading on YouTube. According to al-Ajami’s lawyer Dr. Najeeb al-Nauimi, a former Justice Minister in Qatar, the poem was spoken in a private setting and violated no law. Another of al-Ajami’s poems “Jasmine” was circulated on the internet and expressed support for the uprising in Tunisia and criticized all the Arab regimes.

Sixteen months later, al-Ajami was summoned in Doha and arrested, eventually charged with “encouraging an attempt to overthrow the existing regime,” “claiming that the Emir misused and not abided by the Qatar Constitution” and “criticizing the Crown Prince,” who has subsequently become the Emir. Al-Ajami was sentenced to life imprisonment after a trial held in secret where the Investigating Judge, a non-Qatari, was also the Chief Judge. [The Emir appoints all judges on recommendation from the Supreme Judicial Council, 75% of whom are foreign nationals, dependent on residency permits.] Later on appeal, Al-Ajami’s sentence was reduced to 15 years.

As representatives of PEN International and PEN American Center we—two American women—had come to Doha to argue for the release of Mohammed Al-Ajami, but by the time our planes landed, the court had already upheld the 15-year sentence. All judicial appeals were now exhausted.

A country of two million people, but with only 250,000 citizens, Qatar is one of the, if not the, richest nation per capita. During his reign the former Emir set a course of modernization and brought reform to the government, brought institutions of higher education to the kingdom and developed programs in the arts and set up a Center on Media Freedom. The West looks to Qatar as a leader in the region. The imprisonment of a poet on an offense of lese majeste has confounded many though in an interview, the Prime Solicitor General insisted the charges were not about freedom of speech but were brought because the poet publicly offended people and urged the overthrow of the government.

In Qatar itself the case has received little coverage. The news media is owned by the government and the Emir. Those familiar with the ways of the kingdom say the only recourse now for al-Ajami is a pardon by the Emir. However, if an apology is necessary for that pardon, a standoff may occur. According to al-Ajami’s lawyer, the poet has questioned why he should apologize for having spent the last two years in solitary confinement for sharing a poem in a private setting. His lawyer notes that Al-Ajami has had his career disrupted; he has missed seeing his family for two years, including missing the birth of his youngest child.

As I flew out of Qatar, I stared at the desert below now filled with sky scrapers and modern museums rising from the land. I considered the math. Over 90% of the jobs are occupied by men and women of other countries who have no rights of citizenship and can be deported. Only one in ten people are citizens; half of these are women, who have limited rights; over a quarter are children and the elderly. The country is run by a very small minority. I questioned whether the math was on the side of history.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Extensive gas reserves developed in the 1990’s have given Qatar its huge income and given the country a seat at the leadership tables of the region and the globe. But if the country puts its poets in prison, one must wonder. On the other hand, if the new Emir, just 33 years old, educated in Britain, pardons poet al-Ajami unconditionally as PEN urges, then perhaps the curve of history will extend outwards, at least for a while.

[Mohammed al-Aljami is an honorary member of PEN American Center. PEN’s representatives in Doha were Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Vice President of PEN International and Trustee of PEN American Center, and Sarah Hoffman, Freedom to Write Coordinator for PEN American Center.]

November 14, 2014: Times and Tides

Anniversaries abounded this past week:

—November 11: The hundredth anniversary of World War I was perhaps the most significant. Since I wasn’t alive then, I have no personal memories, but I have an appreciation of its significance in all the years that followed and influenced my life. I also appreciate the misreading and historic mistakes that led so much of the world to war.

—November 9: The twenty-fifth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall—I was around for that. A few months afterwards our family moved to Europe, and I took my children to East Berlin where we walked across Checkpoint Charlie and knocked down the wall ourselves. We still have a bag of the concrete from the wall in a cabinet in our home; the most artistic slabs with colored graffiti we mounted under plexiglas and shared with friends.

—November 8: The tenth anniversary of the second Battle of Fallujah is very personal. We had a son at the front of that battle who survived and is still processing the impact on him and his friends and the country. He has developed into a beautiful writer who tells and has published his own essays and stories. His first novel Green on Blue will be published by Scribner’s this February. Not noted as widely at the time ten years ago were the battles of the civil war in the Ivory Coast. During the Battle of Fallujah I was with African PEN centers in Dakar, Senegal planning a PEN Congress. The headlines on the front pages there were from the Ivory Coast, not Iraq. My heart at the time was stretched across continents. In quiet moments I can still feel…or is it hear?…this beating of the heart.

—And finally this fall celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of my own high school graduation—an unexpected gathering of friends, most of whom I hadn’t seen in a quarter and some in half a century. We found the friendship and goodwill were what had lasted, had roots and still flourished among us.

This flowering and expanding of life and the heart is what I take away. The walls that fall between us are still challenged by the battles fought among us. History repeats or teaches. There are no simple lessons, but to the extent we find ways to break down the walls and end the battles, we hope. Hope after all is still a threshold of history.

November 30, 2015: Democracy in Africa: Who Can Chat with Kabila?

I returned last week from two conferences and a debate back to back in Africa. The Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which has developed an index on good governance and transparency in Africa, gave its annual prize to a former African leader, followed by a day-long discussion on “African Urban Dynamics.”

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

The Africa Report Debates inaugurated its series with the question: “Democracy vs. Development.”

And the International Crisis Group, an organization dedicated to analyzing and offering policy recommendations for current and potential conflicts worldwide, (and on whose board I serve) gathered its Africa program for an internal analysis.

From the gatherings of eminent African leaders, policy makers, scholars and commentators I took away the following contradictions across the continent:

–There is an expanding and active civil society at the same time there are spreading and virulent extremists and criminal networks.

–There are growing numbers of working democracies at the same time entrenched leaders are trying to change constitutions to hold onto power in single-party states.

–There is developing urbanization offering services and employment for citizens while slums and marginalized communities expand.

The debate “Democracy vs. Development” concluded overwhelmingly that the two must go hand in hand.

“Fast and equitable development and diversity come through democracy,” according to Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Ethiopia. But he added, “Democracy is a process. It matures over time and grows from the inside. It can’t be prescribed. It needs institutions and education. We don’t need paternalistic intervention.”

Ethiopia was pointed to throughout as making significant economic progress. But in a break between panels, I asked Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus about the restrictions on freedom of expression in Ethiopia and the number of writers and journalists now in prison there. His answer: “They broke the law.” Their imprisonments have been challenged by major freedom of expression organizations like PEN International, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty, Committee to Protect Journalists, as well as by African PEN centers, I pointed out; this is not a positive sign for healthy government. He and I did not resolve the question between us.

Good news and reasons for hope on the continent include the peaceful elections and transfer of power this year in Nigeria, which has a strong and vocal civil society even as it struggles with the radical extremism of Boko Haram in the North and with criminal trafficking. Also positive is the immanent transfer of power through elections in Burkina Faso, where citizens rose up peacefully last year and opposed the extended 27-year rule of its leader, demonstrating a strengthening civil society. Ghana, where the conferences convened, held peaceful Parliamentary elections while we were there.

“We need heroes,” said Mo Ibrahim, who initiated the conference and the award which was given to the former President of Namibia. Hifikepunye Pohamba won the $5 million prize for “forging national cohesion and reconciliation at a key stage of Namibia’s consolidation of democracy and social and economic development.”

“We must reject the manipulation of the Constitutions,” said former President Pohamba in his acceptance speech. “No individual or group of people should be allowed to abuse power from democratically elected leaders with impunity.”

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Electoral transitions in East, West and Southern Africa could unhinge or advance their regions, including in Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Cameroon, Uganda and Zimbabwe. In many of these countries, the current presidents are hoping to hold onto power past constitutional limits which they are trying to alter or past public tolerance. Outcomes of these elections will be important indicators to watch.

Informal conversation outside the symposiums:

“Who can chat with Kabila?” (President of DRC). “I understand he’s scared. His father was killed here.”

“Who can offer him immunity?”

“Can he have a soft exit?”

“Will he exit?”

“I don’t think so.”

Behind all the statistics and the headlines, the story after all is always about people.

November 17, 2016: Thanksgiving and Healing

The American holiday Thanksgiving is my favorite, a time when family and friends gather and take a moment to give gratitude for the good in their lives and the lives of their communities. This year of 2016 has been a rough one.

In Washington, DC, where I live, the political discourse on all sides has been as uninspiring and acrimonious as any in my lifetime. No matter one’s political affiliation, consensus is that the recent presidential campaign has left us exhausted with the national conversation in need of elevation and inspiration.

Many opposing the election results have taken to the streets peacefully to articulate their concerns and their fears. The crowds include the young—high school students who are not yet old enough to vote—and the retired as well as the population in between. Whatever one’s vote, I take heart that for the most part these protests are not violent and can be heard. I take heart that the leadership in the nation has accepted the transition and will try to make it successful and that in practice we do not jail or shoot opposing voices or those writing about the opposition. This seems a minimum standard for a democracy, and though it has seen exceptions, in this season of thanks, I am grateful and hopeful that will abide.

Historically Thanksgiving was a day to give thanks for the harvest of the preceding year. In the U.S. the first Thanksgiving is documented in 1621 at Plymouth (now in Massachusetts). The harvest was good, and the new settlers and the local Wampanoag tribe shared the feast, though more uneasily watching each other than we were told as school children. During the American Civil War Abraham Lincoln advocated the story of Pilgrims and Indians eating together to try to encourage people in a divided nation to come together.

Healing occurs one action at a time, one forgiveness, one helping hand, one quiet good deed. Citizens can take the lead. I am hopeful that we individually—the people—will build bridges and not walls. Happy Thanksgiving!

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

November 15, 2017: Thanksgiving: History and Healing in Troubled Times

In the U.S. Thanksgiving is a favorite holiday, a time when family and friends come together, pause in their hectic, perhaps fraught, lives to give thanks and consider their blessings. Gratitude remains a most reliable platform upon which to build the future.

My own gratitude includes my loving family. In a break with my monthly blog, I’d like to share a moving Thanksgiving essay by my son Elliot, published in The New York Times: A Thanksgiving Message in a 1963 Proclamation

November 30, 2018: Journey of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving—a favorite American holiday that includes everyone—reminds us to take time to give gratitude and to give. Though Thanksgiving has come and gone, the base of gratitude and the reminder to give in whatever way and fashion builds a foundation that endures and can outlast political, social and even climatic turmoil.

In this space and in this holiday season, I hope readers will share stories and thoughts on this theme. Gratitude and giving are the beginning and end of a redemptive journey.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

November 2019: [Beginning in May 2019 I started writing a retrospective of work with PEN International for its Centenary so posts were more frequent in 2019-2020. In November 2019 there were two posts in the PEN Journeys. The PEN Journeys series completed in October 2020. In November 2020 there were no posts.]

November 8, 2019: PEN Journey 12: Tolerance on the Horizon?

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

It was a time of hope, the year when Nelson Mandela and Frederik de Klerk joined in free elections in South Africa, when Yasser Arafat, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres shook hands and began to live side by side, when the Irish Republican Army and the Ulster Defense Association laid down their arms after twenty-five years of terrorist conflict. The idea of tolerance quivered in the imagination in 1994 even if the realization of tolerant societies still seemed an imaginative leap.

As theme of the 61st PEN Congress, tolerance also challenged the ethnic, national and religious intolerance that gripped dozens of countries in the last decade of the twentieth century. In retrospect the time was perhaps not so different from times since, but we felt we were standing on an historic threshold. The PEN Congress theme of tolerance expressed this hope and optimism.

Liechtenstein Palace, garden view

Writers from over 75 PEN centers* around the world came together in Prague that fall for literary and working sessions. The Congress was a grand affair with public gatherings in stately ballrooms, including the Liechtenstein Palace, home of the Prague Academy of Music. Writers who had been imprisoned under the old Soviet regime, including Václav Havel, now ran the country.

Guests of honor included novelist and poet Taslima Nasrin, whom PEN had recently helped extract from the threat of death in Bangladesh (see PEN Journey 11). For protection she was driven around in a state car, and because Sara Whyatt, coordinator of the PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), and I agreed to look after her, we at times found ourselves whisked from meeting to meeting with a police escort, not the usual transport at a PEN Congress.

Though PEN had no mechanisms to change societies, to the extent society changed individual by individual, PEN worked for the writer, turning a spotlight on cases of abuse and challenging the laws which legitimized intolerance.

The voice of the individual writer has always been the most compelling testimony. My report to the Assembly of Delegates that year as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee focused on those voices:

“Yes, I can hear birds singing. But they are not my friends. They are too far from me. My best friends are spiders and mantis. They are only living things to watch amusedly in my solitary cell. I live and play with them all day long. This excerpt is from a prisoner ten years into a twenty-year sentence written to his PEN minder.

“The image of the spider recurs in the writings of prisoners. One former prisoner I met shortly after taking over as Chair of this committee had come to London to receive treatment for the torture he’d endured. He told of being handcuffed to a generator outside during monsoon season, of not being allowed to wash, using a bucket as a toilet, his arms and hands wrapped around the generator for weeks. Then he talked about being inside in solitary confinement. ‘I had a chance to observe nature: rats, cockroaches, spiders,’ he recalled. ‘Ah, spiders, they are brilliant!’…” [cont]

November 20, 2019: PEN Journey 13: PEN and the U.N. in a Changing World

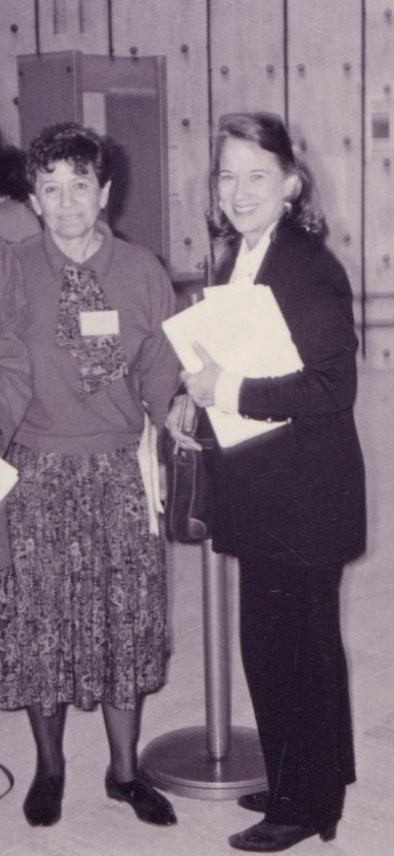

We sat on one side of the dining table at the embassy in Geneva drinking orange Fanta—Sara Whyatt, Coordinator of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), Fawzia Assaad, member of Suisse Romand PEN and liaison for PEN at the UN Human Rights Commission, and myself, Chair of PEN International’s WiPC. On the other side of the table visibly sweating sat three diplomats from North Korea.

(l to r) Fawzia and Joanne at UN Human Rights Commission

The week before, U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher had visited the same embassy. The United Nations Human Rights Commission was meeting in Geneva, and PEN, which had consultative status at the U.N., had sent us as representatives to the Commission meetings with targeted cases and country reports, including one on North Korea. The year 1994 was a time of potential thawing in relations with North Korea, and the diplomats on the other side of the table were telling us how they would like to have a PEN Center in North Korea.

Fawzia, who was ready to reach out to people, agreed that could be a possible step, but Sara and I gently nudged her under the table and explained that there were certain important criteria in a country for a PEN center to exist. The criteria included some measure of freedom of expression and an acknowledgement of this value though admittedly the extent of freedom varied in countries with PEN Centers. We asked if writers and their families who have been separated since the war might meet on neutral ground. The Counsellor answered, “Why not?” We asked if North Korea would open itself to visits by writers from abroad to discuss freedom of expression. The Counsellor again answered, “Why not?” We agreed that a first step could include an exchange of writers.

As the dinner and conversation proceeded, we all noticed the visible discomfort and sweat on the brows of the diplomats. We later speculated who might have been listening, perhaps on a device or behind the curtain on the other side of the table. Finally the young daughter of the senior diplomat was introduced to the room and entertained us on a traditional Korean musical instrument which she played as she sang Swiss folksongs.

The meeting was one of the more surreal in my tenure as Chair of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. None of our requests came to pass, and it wasn’t until almost two decades later in 2012 that PEN finally welcomed a North Korean PEN Center In Exile, whose members had managed to get out of North Korea with harrowing stories of escape. [Ref. JLA blog Sept. 2012]

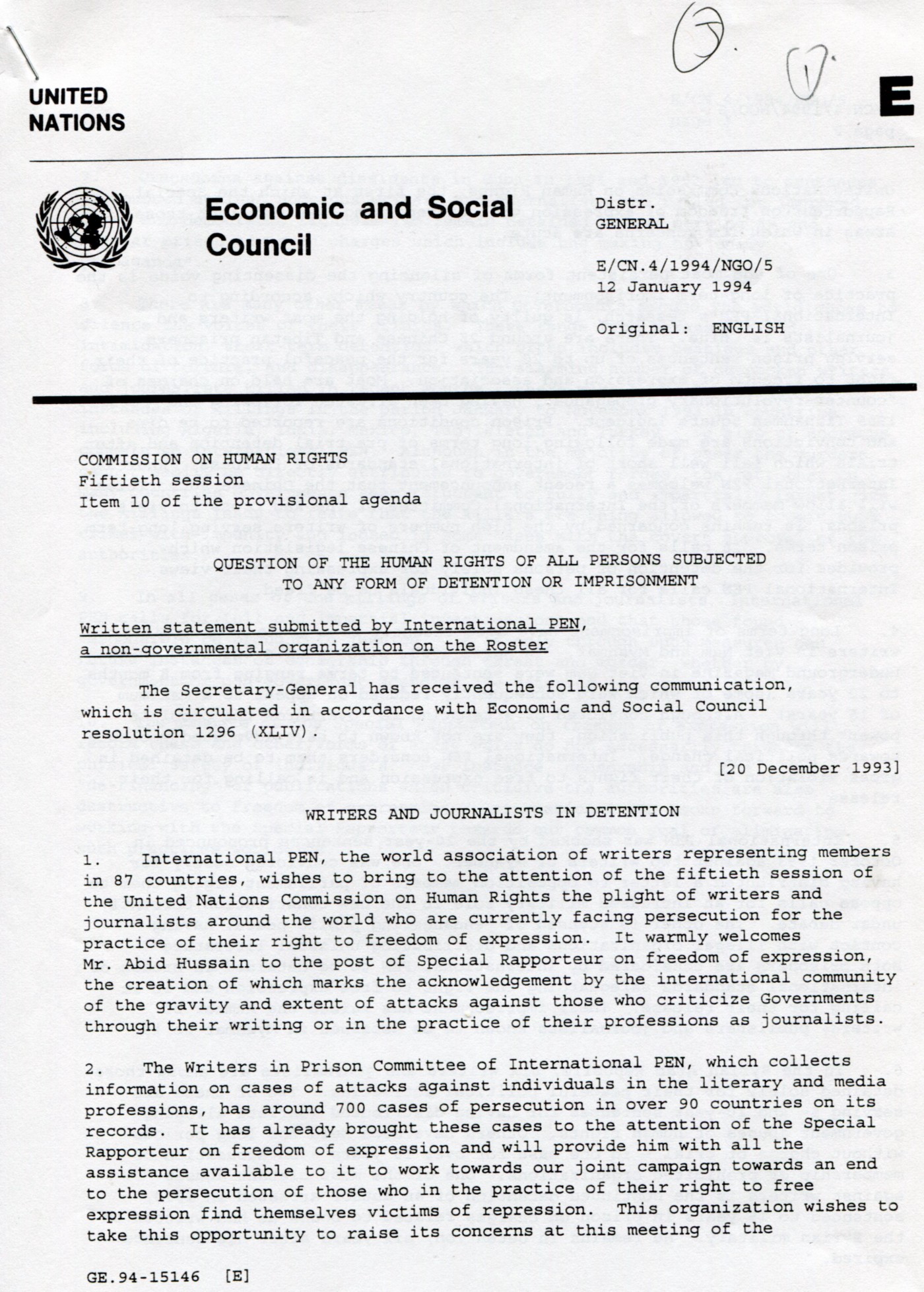

Page 1 PEN International’s submission on Detention and Imprisonment of Writers and Journalists to the UN Human Rights Commission

For the past 70 years, PEN International has maintained consultative status at the United Nations. This status has meant that PEN International’s reports and activities are both supported through UNESCO funding and are received and considered in UN forums, particularly at the UN Human Right Commission and in UNESCO.

After World War II UNESCO, whose mission was “building peace in the minds of men and women” through education, science and culture, looked to start organizations in these sectors. For theater and the arts it created the International Theatre Institute which creates platforms for the international exchange and engagement in the performing arts. However, when it came to creating an organization for literature, UNESCO recognized that PEN already existed, and so it has worked with and supported PEN congresses, conferences and programs around the world. These programs have also included the work of PEN’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC) which developed the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights, also known as the Barcelona Declaration, passed by PEN in 1996 when the current Executive Director of PEN International Carles Torner chaired the TLRC.

Though PEN continues its relationship with the U.N., UNESCO’s budget has declined over the years as has its financial support and PEN’s dependency. PEN officials, including myself, have still visited UNESCO headquarters in Paris and UNESCO representatives still attend PEN conferences and congresses. But the change in both funding and governance for PEN International can be traced back to the years of the fin de siècle when governance around the world was challenged to include wider democratic vistas.

At PEN’s subsequent congress in Perth, Australia in 1995, conversations began regarding a change in governance for PEN, and by PEN’s 75th Anniversary in 1996 at the congress in Guadalajara, Mexico, the momentum for change became inexorable.

But first, meetings in Bled, Slovenia with the Peace Committee and further campaigns on writers threatened around the world.

PEN Writers in Prison Committee Centre to Centre newsletter, Aug/Sept. 1994

November 2020: No blog posted