Message to Tomorrow…

At the threshold of a new year, stepping out beyond the footprints of the old, I walk on.

The known and unknown ahead.

And the unexpected.

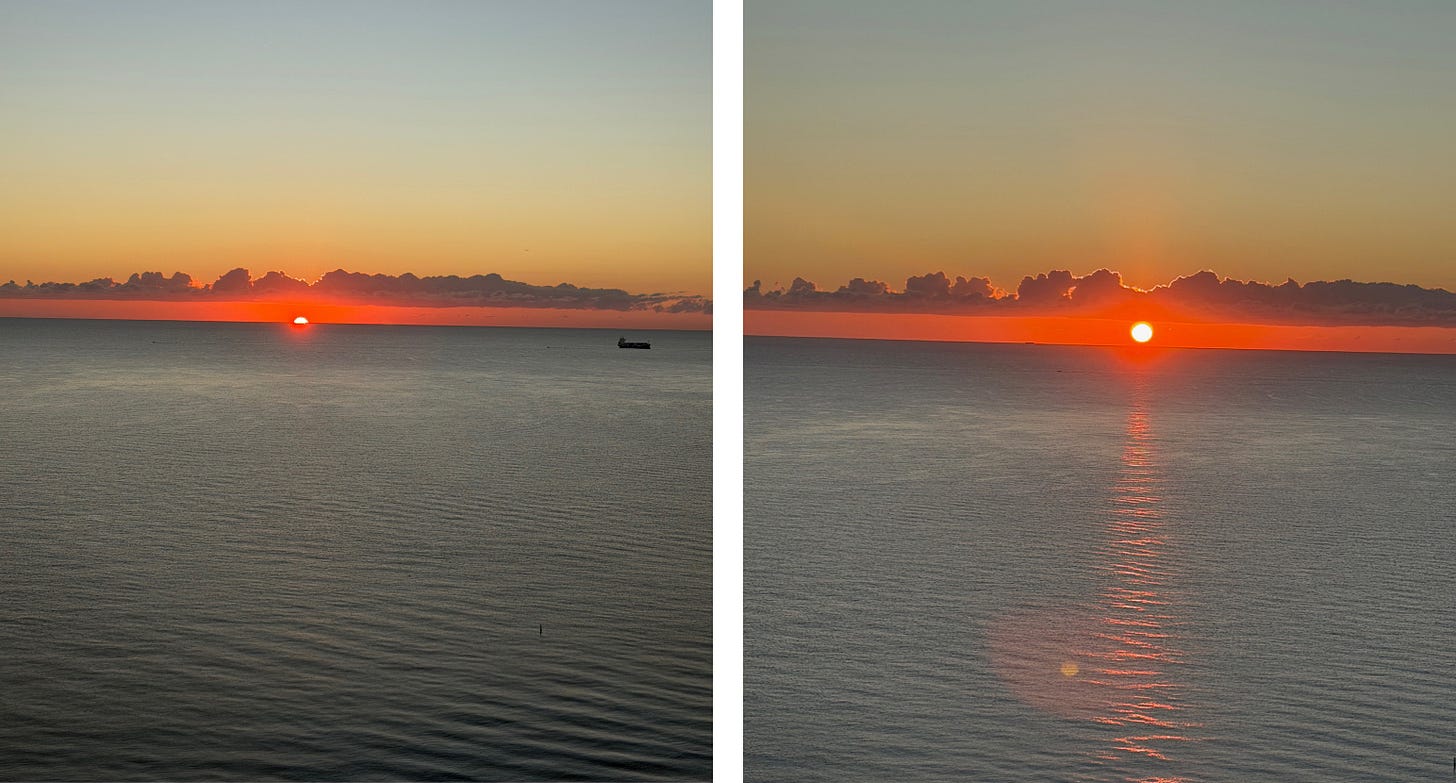

I choose a red, not a white car to drive into the new year on the roads and highways of this new destination in Florida…by the beach, by the ocean with the surging Atlantic and the sun rising on the horizon every morning out my window over the endless water.

Changing Latitudes, Chasing the Sun, Voting with Consequence

Geese are starting to fly South, squawking over the river in formation. At least I think theirs is a southward journey. It might just be a Saturday morning field trip, but I haven’t seen any flying in the opposite direction. It is not yet winter, and as I sit by the river this morning facing east with the rising sun in my face, I am pleasantly warm in only a bulky sweatshirt and pants but am told by the weather forecasters that an arctic wind is on its way. The geese are honking all around the river so I think they already know it is time to hit the road or the air.

I began this column in early November on the Eastern Shore of Maryland but won’t post till December. My intent is to offer more than a weather report and subtly—is it subtle?—to speak on larger issues. By the end of the month I will have moved South to Florida. I will vote there in the next election, and for the first time in 30 years my vote may have consequence for in the District of Columbia where I have been a resident for the past decades, the voter has no national representation—no Senators and only one Representative who doesn’t have voting rights in the Congress. The city is heavily one party so a single vote has slight impact. Not that one vote has profound impact anywhere, except that it does. Over these last decades we have learned that one vote, two votes, each citizen’s voice can make a difference. I will find out.

I will still toggle between north and south, but having landed in the state of sunshine and palm trees, I am looking forward to this change of latitude. I am now watching the sun rise on the terrace of a restaurant that doesn’t open till dinner, looking out over cars on the road and a beach just beyond with freighters on the horizon. The geese haven’t gotten this far south yet. I don’t know if they ever arrive in Florida. I will find out. There are occasional sea gulls. I will miss the geese and ducks but will see them again in the spring and summer when we both return, and meanwhile starting next year, I will vote again, perhaps with more consequence.

Tunnel of Hope…Past and Present

Wars end, eventually.

In the middle of war, the end is hard to imagine, and the aftermath unpredictable—devastation restored, justice reconciled, the younger generation taking over…or not? At the moment focus and hope is on a possible peace in the Middle East between Israel and Palestinians. In Syria citizens are also in a suspended state of optimistic but cautious hope and skepticism after 13 years of civil war. Other areas of the globe remain locked in conflict.

Recently I returned for a 30th anniversary of the Siege of Sarajevo. During the nine-year Yugoslav Wars (1991-1999) as the country broke up, Serbian forces surrounded the Bosnian city of Sarajevo, blockading it and cutting off food, water, gas, heat, all power, and weapons. Shelling Sarajevo from the surrounding hills 24 hours a day, dropping over 500,000 bombs, Serbia’s 13,000-man force tried to break the will of the citizens, but the Bosnians refused to give up.

Digging for four months, they built an 800-meter tunnel from the airport where the United Nations had control. Through the Tunnel of Hope Bosnians managed to ferry supplies into the city. I remember a Slovenian writer and colleague of mine in International PEN who ran that gauntlet more than once with funds and supplies donated from writers around the world for our colleagues in Sarajevo.

Lasting from April 1992 to February 1996, the Siege of Sarajevo was three times longer than the Battle of Stalingrad and the longest siege of a capital city in modern history.

Last month I arrived for a 30th anniversary board meeting of the International Crisis Group, which was born out of that conflict when three international professionals envisioned an organization that could put top researchers on the ground to discern truth from propaganda and work with a board of high level ex-presidents, foreign ministers and diplomats from around the world who could advise and pass on suggested actions and also operate as a backchannel. Though I’ve never served in government, I was active with nongovernmental organizations and asked to join the board from the second board meeting of the International Crisis Group. I served for 22 years and got a global education in the process. The October 2025 board meeting in Sarajevo was a reunion for many of us and reminded us that even out of one of the worst conflicts, peace can be born.

The day before our gathering, I arrived in Sarajevo and had a guide take me around. Thirty years ago he had been a student and an athlete, a runner, but like most young men he joined the resistance and special forces. He lost part of his leg in the conflict, but he worked for the resistance the whole four years. He lost half of his friends in the conflict.

“We fought and worked in six-hour shifts, then slept six hours, then spent six hours protecting the churches, synagogues and mosques,” he said. Sarajevo took pride in being an ecumenical city where all religions were welcome, he explained.

He told me that when the siege started, he lived at home where his mother loved books and reading and had a library of over 1000 volumes. When the siege was over, she had only two books left because the family had to burn the books for fuel. They also burned their floorboards.

Sarajevo has been largely restored now with modern buildings, hotels, and shopping malls, but some of the bombed-out buildings and those shot with mortars are left standing along the roadside and highways as reminders. The memories abide. How the population functions with those memories a generation later is an ongoing story.

Before the war, Bosnia had Christians, Muslims and Jews, Serbs, Croats and Bosnians all living together. That easier peace has not returned, but there is no more violence of war, and the peace is a daily job.

Sarajevo has a unique history in Europe and the world, for it is also here that the spark for the First World War was lit with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. Shot by a Serbian nationalist in 1914, the Archduke’s murder heightened existing tensions between Austria-Hungary and Serbia and led to an ultimatum then declaration of war. This triggered a complex system of alliances that ultimately brought the major European powers into war.

“People don’t want conflict,” insisted my guide, now a father himself. But how to keep the peace is up to each of us, he said.

We Are What We Think…and Eat

Walking down a familiar stretch of M Street in Georgetown in Washington DC, I noticed a new restaurant among the surrounding restaurants, all featuring foods from different regions of the world side by side in this half block—France, Afghanistan, India and an “Asian grill.” A half mile away are Mexican restaurants and across the street Ethiopian and Vietnamese restaurants. In this small neighborhood can be found restaurants with their chefs and staffs from most regions of the world.

The rich culinary offerings represent a heritage we have as Americans. Most of us at one point in our families’ histories came from immigrants arriving on the shore of this country that promised “liberty and justice for all.” Some began by starting restaurants with the food from their home countries.

America receives immigrants from 112 countries, according to 2016 statistics, a factor that has countered the declining population rates seen in many countries like Russia. U.S. immigration policy, however, continues to be debated and remains unresolved. Most Americans agree there need to be rational, enforceable immigration limits but with humane enforcement. Yet enforcement in the past year has never been as harsh and unwelcoming nor the national discourse as contentious, at least in my lifetime.

The discordant rhetoric also seeps into personal lives. I recently had conversations, one with an octogenarian, one with a young teenager—both included sentences beginning with a passionate “I hate…” The object of one was a political personage; the other a contemporary.

However justified hatred may seem, it doesn’t lead to the society we want to live in or to the actions that will build and benefit. Countering hatred can seem difficult, especially if the offense seems personal or existential, but hatred is a false foundation that cannot bear the weight of living. Hatred is as corrosive as any drug or poison or weapon to a person and to a society.

Hatred is countered thought by thought and action by action. Kindness, generosity, even if not reciprocated and even if not necessarily directed at the object of hate, can begin to fill thought and to crowd the hatred out.

Detecting the Counterfeit: Lies, Flimflam and the Real Deal

The swirl of political events spin in the headlines relating to wars and conflict, profound misdeeds, voting manipulations, deceit among leaders, all having profound consequences in my country and others.

I found myself typing words to focus my thoughts—lies, truth, love, counterfeit…Counterfeit, a word and idea to explore. “Counterfeit—An imitation intended to be passed off fraudulently or deceptively as genuine.”

How does one tell the truth from a lie, the real from the counterfeit in history, politics, and life? Is the answer only subjective, determined by what one wants to see and believe, an illusion propped up by those who agree with us or alternatively those who claim power over us? Such is the path of authoritarian regimes who rewrite history and events as they want them to be seen and recorded, who remove books, and therefore ideas, from the shelves, and eventually close down or limit free expression.

The best way to detect a counterfeit is to know the genuine article and have it at hand to compare. For example with currency, the U.S. Treasury goes to great lengths to make counterfeiting extremely difficult because of the intricacies in design and production. The texture and composition of the cotton and linen paper is unique with tiny red and blue micro-fibers embedded and with slightly raised printing and with color-shifting ink on larger bills when tilted towards the light, with numerals in the lower right that change color from copper to green, and a 3-D security ribbon on the $100 bills woven into the paper causing images of bells to move up and down or side to side within the ribbon.

Holding a bill to the light reveals some of these hidden features. Some bills have watermarks to the right of the portrait visible on both sides when held to light. Also, micro printed words such as USA are on certain bills, and all have exact detailed printing especially on the borders and seal.

The list continues of what is necessary for a bill to in fact be genuine U.S. currency. However, not everyone is vigilant when accepting currency, and these lapses of attention are what the fraudster is counting on when passing counterfeit money.

The safeguards in a democracy are equally fine-tuned and time-tested. These include rule of law, due process, independent judiciary, equal justice, free and fair elections, robust checks and balances on executive power, freedom of expression and the press, counters to disinformation and promotion of civic engagement. But if these safeguards are set aside or ignored, the real democracy will fade, and a counterfeit will emerge. In numbers of counterfeit democracies like Russia and Venezuela, elections are held but manipulated; opposition candidates are discouraged or even killed; the press is constrained, journalists detained or also killed, and the law is subject to the opinion of the ruler: “If I say it’s law, it is law.”

Freedom House, the U.S.-based non-governmental organization notes in its Principles for Safeguarding U.S. Democracy “…The United States, as the world’s most influential democracy, has an essential part to play in the global struggle for liberty. It has a unique capacity and a moral obligation to cultivate alliances with free nations and lend support to democracy advocates in authoritarian or transitional settings. Doing so ultimately protects the freedom, security, and prosperity of Americans by promoting a stable international order, preventing armed conflicts and failed states, and ensuring the support of like-minded global powers. The United States cannot play this role if the country’s own democratic institutions continue to erode, as it will not have the internal capacity or the international credibility.”

If citizens cease paying attention, if voices are silenced, if certain voters are hindered from voting, if rule of law is set aside and ignored, if courts fail to uphold laws and immunity gives unchecked power to the executive, then the counterfeit of democracy slips into place. The challenge for a counterfeit democracy is that it doesn’t have the true power of its citizens engaged. If counterfeit currency floods a country’s system, the value of the real currency becomes worthless, and runaway inflation results. A democracy which has lost its freedoms has lost its power.

“The truth will set you free,” the Bible assures, because real power derives only from what is true.

Finding Kindness and Heroes

Last month’s Substack essay “In Search of Kindness” follows up here with acts of kindness observed.

I was recently visiting my old neighborhood in London where I used to live, walking down High Street Kensington on a sunny July day. The High Street was bustling with people—residents, tourists, children, darting in and out of the High Street Kensington tube station and in and out of shops and hurrying on to their next destinations. I was on my way to a favorite restaurant when a diminutive woman in a loose blue shirt caught my eye. I was walking behind her. She had short grey hair and was slightly bent over, a person you might not notice, except I noticed that when she passed an elderly man folded into a doorway with a paper cup in front of him, she reached into her purse, took out several coins and went over to him and dropped them into his cup. No one else had noticed him.

Half a block later another elderly man with a full gray beard sat in the corner of a building on the High Street playing tentatively on a guitar. Again, she reached into her purse and made the effort to move across the insistent flow of pedestrians and dropped a few coins into his guitar case. No one else was stopping. This was not the mission of her outing, but she paused and took note of these people then went on her way.

I was certain she would do the same for the next itinerant down the block. I stepped up beside her and said, “You’re a good woman. I saw you helping.” She looked over at me surprised that I’d noticed then she smiled. “It isn’t going to hurt me to give a little,” she said.

“You saw them and showed that you cared,” I observed. She appreciated this insight.

“They are often here,” she said. Our conversation wasn’t long, and she went her way into the shops.

I had no coins, living as we do now by credit cards, not cash, but I went into the next shop and got cash and filled my own pocket with coins. I think we both understood that these coins would not solve the problems of unemployment or homelessness, or perhaps even be able to change much the circumstances of those who’d slipped into the corners of the street, but the gesture at least showed that they were seen. Those few who were also playing musical instruments—guitars and violins which perhaps were once tools of their trade—also shared music with the street as pedestrians rushed by.

One cannot fund all who find refuge on street corners these days. And it is important in giving not to be funding habits of drugs, but many have simply fallen out of the system of employment or social services. The larger societal answers are left to those who work in social service organizations or government agencies. I recognize that giving a few coins or bills is neither the answer nor everyone’s responsibility, but I also noticed how few in the hundreds rushing by paused or noticed. Have we gotten numb to hardship, perhaps even annoyed by it, even receptive to those who blame the victims?

While in London, I went to the theatre and saw a play “Till the Stars Come Down” about a Midlands English family wedding where the prejudice is against the Polish groom in a town where coal mines have closed. At one point the Polish groom says to his unemployed and prejudiced brother-in-law to whom he’s offered a job: “You need to decide if you’re a victim or superior because you can’t be both.” The play’s theme threads through the story and characters, demonstrating the corrosive nature of prejudice which can hollow out the heart, feelings and human spirit, whether that prejudice is racial, national, religious, or…

The same day I observed the elderly woman reaching into her purse on the High Street, a news story was reported out of France about a caretaker at a public middle school in Paris who arrived home tired after a week of work, but instead of resting heard a fire alarm nearby and went to check it out. There he spotted a woman and her children trapped by the fire calling for help. He climbed onto a ledge of the sixth floor where he took the children from the burning building one by one and got everyone, including two infants and the mother—six people—to safety.

He scaled the building to help. “I went on instinct,” he said. “It’s the heart telling you, ‘No, you have to go.’”

It is the heart telling you.

In Search of Kindness

Nobel physicist Albert Einstein advised: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking that created them.” He urged a new way of thinking.

I’ve taken this observation as a guide, a touchstone of thought and problem-solving, be the issue personal, political or cosmic. Often the first instinct is to get pulled into a problem and begin wrestling within its borders to find an answer. In the political sphere when intolerance and cruelty appear to govern policy and actions, it is challenging not to react with condemnation and anger even if the actions aren’t directed at me or mine.

I grew up in the South, in Texas and spent younger years arguing civil rights with friends and family, upset by the intolerance and injustices I saw and read about. Eventually, I left Texas and studied and got to see a larger world. I read and learned history. I also learned to look into the heart and not just the politics of people.

One essay I studied was Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” in which King declares:

“Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust…Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly…And Thomas Jefferson: ‘We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal…’ Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.”

These words still echo. Jefferson’s declaration that “all men are created equal” didn’t specify race or religion or even nationality (and now is assured to include women). The words set out a universal truth that was later echoed in such documents as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which the world is still trying to live up to, including those 48 nations which originally signed it.

To that end one can perhaps start with kindness.

At the core and in the DNA of America is a commitment to individual freedom and liberty and to generosity. When policy violates this, I don’t think it will stand, at least in the long run.

My domain is words and of course my own deeds, and so day by day I am committed to and in search of kindness.

Devastation & Destruction or Resilience, Reimagining and Rebuilding?

The young woman next to me sat silently at the table for the first hour of presentations and discussion. She was younger than the other women, with long dark hair, frailer than the more robust women around the table. Her slender fingers touched tentatively the papers in front of her.

I was in Honduras with CARE, the humanitarian and development non-governmental organization (NGO) which has worked in Honduras for 70 years.

The women at the table were sharing their stories of the violence they had suffered and the way they came back from the brink, a precipice that caused several of them, including the woman next to me, to contemplate suicide. The only other possibility they saw to survive was to migrate to a safer place like the United States. Most had children and had resigned to taking their children with them. The violence against them was domestic and also from the gangs that surrounded their community. Police told them they couldn’t get help when they were threatened, only when they were actually harmed, and even then, very few perpetrators were prosecuted. Impunity prevailed. Doctors told them not to clear away the blood from their faces when they were beaten; otherwise, they had no evidence.

They didn’t want to leave. Honduras was their country and home, but alone, they didn’t know how they could survive. Honduras has one of the highest murder rates against women in the world. Several concluded if they didn’t leave, they would be killed and so they left with their children. But the escape was equally dangerous. Several had been raped again or kidnapped, and some of their children were also abused or died on the journey.

Finally, the woman beside me spoke up. She was 29 though looked younger. She had a 6-year-old son and was one of these women described. She appeared frail, but as she recounted her attempt to find safety and a life for herself and her son, her quiet voice gained confidence and volume. By the end of the story of her perilous journey and her progress, many of us listening thought she could run for community office because of her courage and quiet charisma, though of course politics could be a perilous journey of another kind.

Like many of the women around the table, she found a safer place, developed a business of her own and some protection and resources for herself and her son. This came from the community of women in a Women’s Network, aided significantly by funds from the U.S. government—USAID—with CARE and the local organization CASM developing and implementing the “Women Weaving Free Lives from Violence” program that serves 112 communities and approximately 32,000 people.

However, the recent shutting down of U.S. foreign assistance with the large reduction of USAID, has meant this program has had to cut back significantly, and other programs have had to shut down entirely. CARE through its own Triage Fund continues to work with these communities but on a much more limited basis. “Seeding Hope,” a program offering leadership training, small business support and safe spaces for at risk youth who have faced violence, displacement and also uprooting because of hurricanes has been canceled entirely.

Many of the women in this region have worked in textile factories making clothes and items which ship back to the U.S., including MAGA caps and swag. But many of these factories have now closed.

A program “Nourishing the Future” has worked for years with small-scale farmers through Farmer Field and Business Schools equipping farmers with training in the best agricultural and business practices. With this training farmers have significantly increased their income and also been able to practice “climate-smart” agriculture such as using a biodigester apparatus that transforms animal waste into useable fuel and saves on burning firewood. The programs have also been supported by the Cargill Foundation so can continue but have had to reduce in size.

These programs with farmers and with women have enabled community-led savings groups (VSLAs) which provide access to some capital and increase the income and stability for communities which in the past could not get credit.

“If you don’t get trained, you don’t get out of poverty,” said one farmer.

“Education gives us an opportunity to have a better life,” added another.

“We needed a way to make a living,” said one woman.

“We needed entrepreneurship workshops,” added another.

“You can’t do things by yourself; you need someone to walk with you.”

On returning from Honduras, I am left with the voices of the women and youth and farmers whom we met, with Ely who started a small food stand with $40 and after training now has a popular restaurant where we had lunch and where her supportive husband works for her. All express appreciation for assistance received and have a determination to take what they have learned forward and share it with their communities. But they also express a deep regret that the United States government can no longer be counted on as a robust partner in the development of their country whose GDP per citizen in 2024 was $3446. The 2024 per capita GDP for U.S. citizens was $85,784.

Searching for Place de la Concorde

I walk through the Tuileries Garden on a sunny Sunday morning in Paris with all the celebratory marble gods and generals along the broad path, with flowers and children and families, with the Musée de l’Orangerie and Musée du Louvre nearby and the Place de la Concorde (Harmony Square) ahead.

The 19-acre Place de la Concorde is the largest public square in Paris with the majestic Luxor Obelisk at its center and a view of the Arc de Triomphe and the Eiffel Tower in the distance and statues of Hercules, Caesar, Theseus Fighting the Minotaur, Artemis with a Doe, A Tigress Carrying a Peacock and many other figures filling the landscape. The fountains and ponds sparkle in the sun which shines on these relics of a fraught and troubled history that has now settled into a sightseers’ bonanza.

On this very ground a mere 232 years ago were the public executions by guillotine of King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette, and eventually of Maximilien Robespierre, along with a thousand more during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror in 1793-1794. The square was named Place de la Révolution at the time, but after the revolution, as a gesture of reconciliation, its current moniker was adopted. Surrounding Place de la Concorde are now luxury hotels and buildings of state.

From this majestic city with its history now enshrined as tourist attractions, I move on to Amman, Jordan where I join others in a fact-finding, listening journey with the International Crisis Group into the unsettled situation in the nearby countries of the region. Here history harks back many millennia, all the way to the Bronze Age and to places like the ruins of Jerash which remind current tourists, of which there are fewer these days, of the fleeting notions of time and politics. Unfortunately, the latter has a grip on the region that seems difficult to loosen and resolve.

Our discussions with former ministers and current journalists and scholars fixed on the seemingly intractable struggle between Israel and the Palestinians, with an additional focus on the future of Syria. There are glimmers of hope in the talks, but these are few and just bare glimmers, though one grasps onto them and probes how they might be developed and expanded to light a path forward.

This blog is not sufficient for that fuller discussion except to note that as one observes and walks through history, the path does at times open in unexpected ways, though often there is brutal conflict before that opening occurs. Everyone we meet with is still talking and looking for a way to find that path.

Back in the U.S. where I live in Washington, DC, the body politic is in its own struggle and is as stirred and upended as I can remember in my lifetime. Protests and court challenges unfold weekly, if not daily, in the concern that an authoritarian wind is sweeping though with actions taken outside of legal bounds.

My few weeks away put in some perspective the fraught history that has come before and emphasizes that Place de la Concord (Harmony Square) cannot be taken for granted.

Conflicting and opposing views of citizens and leaders have always challenged, but over time societies have found that through compromise, institutions, laws, respect for fellow citizens they can progress and find a way to exist in spite of differences and even advance because of these. Retribution is not an engine for a just and fair society. Respect for the individual and for the law allows differences to resolve and dissent to breathe and disagreements to resolve nonviolently.

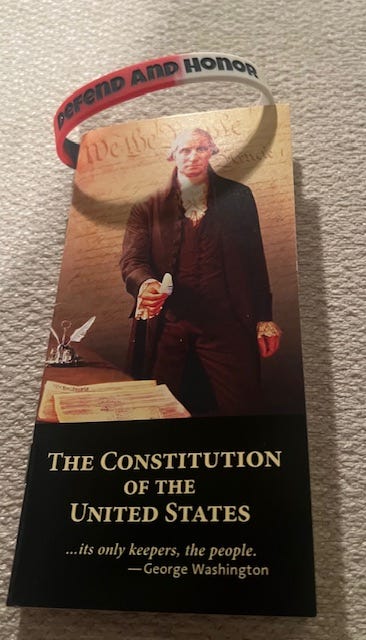

Concerned about how to respond and speak up to the rapid and often seemingly illegal changes taking place, one friend who has lived in the political arena most of her life took a small step of her own. She ordered paperback copies of the U.S. Constitution then created and ordered red, white, and blue rubber bracelets that say: “Defend and Honor Your Constitution.” She carries these with her for any political discussion or debates which erupt; there are more and more these days. Trying not to get swept up in the rancor of the moment, she quietly hands out the Constitution, urging her fellow citizens to read and remember the provisions of this document which has been a model for the world over, then she hands out a bracelet. I’ve been wearing my bracelet ever since.

“…Under the empires of old, the strong did what they willed and the weak suffered what they must.

But over the centuries, people built the sinews of civilization: Constitutions to restrain power, international alliances to promote peace, legal systems to peacefully settle disputes, scientific institutions to cure disease, news outlets to advance public understanding, charitable organizations to ease suffering, businesses to build wealth and spread prosperity, and universities to preserve, transmit and advance the glories of our way of life. These institutions make our lives sweet, loving and creative, rather than nasty, brutish and short….”

—David Brooks, Column in New York Times, April 17, 2025

NYT Article by Ryan Holiday, April 21, 2025:

The Naval Academy Canceled My Lecture on Wisdom

How a lecture to the U.S. Naval Academy on censorship was censored.

Roughly an hour before my talk was to begin, I received a call: Would I refrain from any mention in my remarks of the recent removal of 381 supposedly controversial books from the Nimitz library on campus? My slides had been sent up the chain of command at the school, which was now, as it was explained to me, extremely worried about reprisals if my talk appeared to flout Executive Order 14151 (“Ending Radical and Wasteful Government D.E.I. Programs and Preferencing”).

When I declined, my lecture — as well as a planned speech before the Navy football team, with which my books on Stoicism are popular—was canceled…

Competing Voices: Warbling in the Dark, Singing in the Morning, Searching for a Symphony

Carolina Wren, Canadian Goose, White-throated Sparrow…birdsong at dawn on a Sunday morning.

The light has shifted and arrives later now that daylight savings is over. More bird sounds rise as the weather warms. The birds appear to harmonize and get along with each other with their different pitches and warbles and squawks. Most sing from high in the trees, out of sight, occasionally flying overhead. The geese and ducks glide silently on the water but talk to each other from the air.

I sit in the gathering light and listen to the birds chirping and trilling on this chilly March morning. The sun is about to break over the trees on the horizon. Here it comes…a full golden orb ascending…coming quickly now so that I can’t write about it and take a photo at the same time before it is fully above the horizon.

My dog sits beside me and is also listening to the birds and watching the sun rise. I wonder what she sees. I’m told dogs only see in black and white…what they miss of the resplendent golds and greens and blues. But she hears sounds I don’t hear. Before I hear or see the squirrel approaching the bird feeder, she races off, and (thankfully) never catches the squirrel who defies her with its own special power of scrambling up trees. I don’t think my dog is predatory so much as territorial and just wants to play and to chase.

The animal and aviary kingdoms have much to teach us, perhaps more than ever these days. I hesitate to romanticize, but of course that is what I’m doing. I’m sure there are hierarchies among the animals and even among the birds, but they appear to get along better and to abide with their differences, not to cancel out those they don’t agree with.

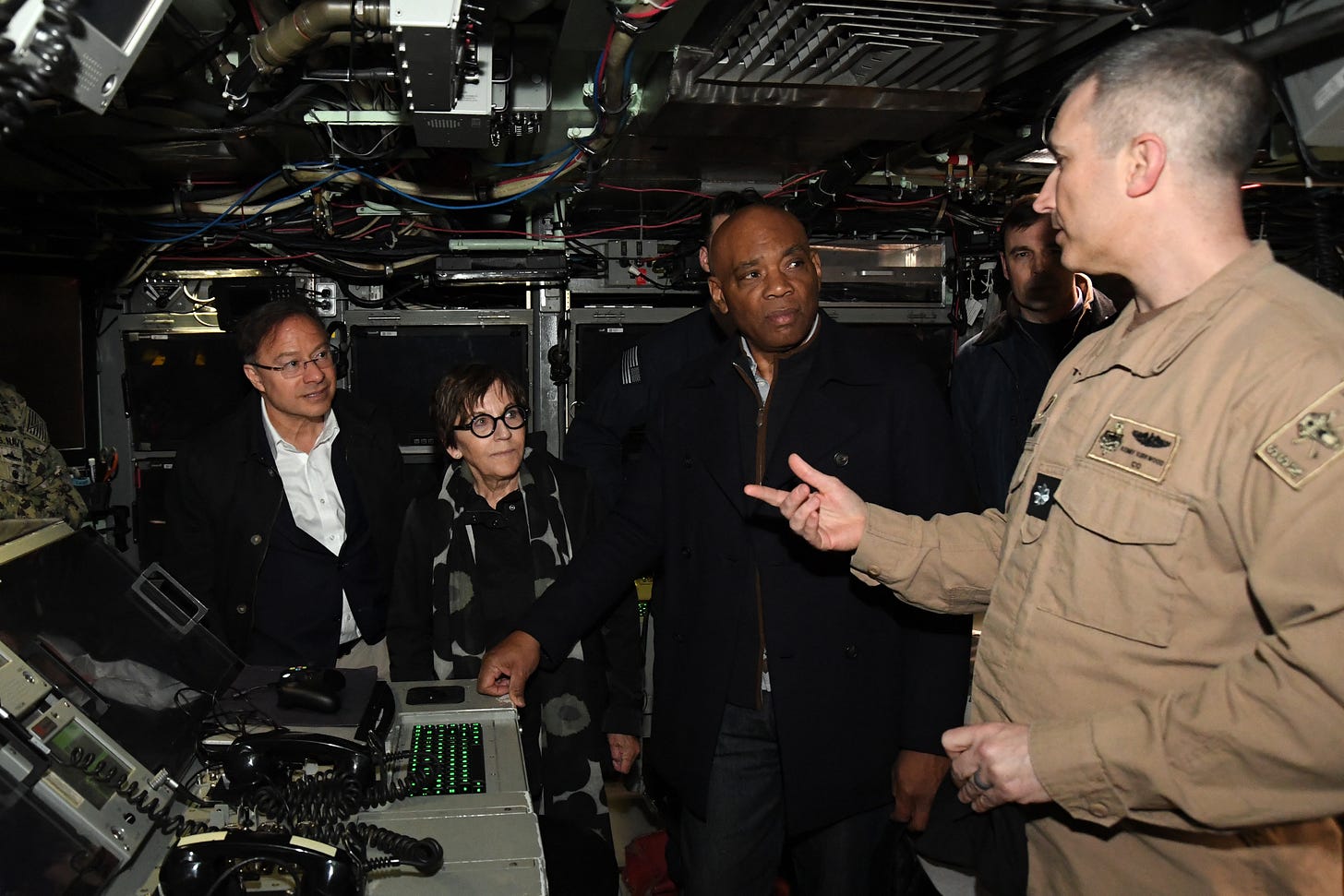

Back among the human species and body politic, I recently visited, along with other members of the Council on Foreign Relations, the “Submarine Capital of the World” in Groton, CT where submarines are built and docked. In touring inside one of the submarines, we saw and tried to imagine how 130 men (and some women) existed together for eight months in spaces not much larger than the size of a coffin, moving along corridors barely as wide as a person, with missiles and torpedoes at bedside and cables and electronic equipment running throughout. It clearly takes accomplished sailors and those who know how to live and work in extremely close quarters. It also takes leadership that encourages and helps foster the bonds of community. An understood and shared mission helps, but it must be more than that. It must be a commitment to respect each other and operate as a community in spite of differences. I’ll resist romanticizing these submariners, but those we talked to were committed to their vocation and to getting along with each other.

These days there is a need for such lessons among our citizenry and our leadership, and if leadership at the top doesn’t have that goal, then person by person, day by day, action by action, citizens I hope will.

[Along the same theme I hope you’ll find of interest two articles, one about the White Helmets helping in Syria in the March 25, 2025 Christian Science Monitor and the other “The Politics of Love in Turkey’s Protests” in the March 26 Christian Science Monitor.]