The Longest Day in a Spinning World

The summer solstice June 21 slid by on a cloudy chilly day with buckets of rain on the Eastern Shore of Maryland so that I barely noticed the longest day.

As summer officially begins, the light starts to retreat as the earth tilts slowly away from the sun, at least in the northern hemisphere. Whatever the vagaries on the surface—politics, wars, elections, hurricanes, coups or celebrations—the earth moves imperceptibly beneath our feet.

For me, June before the solstice meant a week in Chicago with book events, significant for my new novel Burning Distance and for an interview with Lisa See about her new novel Lady Tan’s Circle of Women and an energized discussion with novelist Sara Paretsky about censorship and banned books, the latter events at the American Writers Museum.

For me, June before the solstice meant a week in Chicago with book events, significant for my new novel Burning Distance and for an interview with Lisa See about her new novel Lady Tan’s Circle of Women and an energized discussion with novelist Sara Paretsky about censorship and banned books, the latter events at the American Writers Museum.

On this trip, I fell in love with Chicago, a city I’ve visited before but never for as long a stretch. Walking along Michigan Avenue from Millennium Park with detours down to the Chicago River and up to the rooftop of London House, I passed (and contributed to) a musician on almost every street corner playing the sax or French horn or violin or music from a box. I had a soggy sprint to an opening night of a new musical at the Goodman Theater.

While the earth spins beneath us, Chicago reminds us to enjoy the moments—cold or hot, windy or still, pouring rain or bright sun (sometimes all in the same 24 hours)—and to enjoy the music.

The song heralds: “Bet your bottom dollar, you’ll lose the blues in Chicago.”

And the universe echoes back!

Mothers in the World

The one commonality around the world, in every country, every religion, for every sex, race and culture is the mother. We have fathers too, though paternity is not always as clear.

When I travel in different countries and cultures, be it in Africa, Asia, Latin America, in communities whose language I can’t decipher and sometimes without a translator, I can usually communicate with a mother and her child. Even hardened men yielded to a mother.

I remember a colleague who was a mediator and also a mother. She was once tasked with retrieving children from a notorious warlord in a country which had recruited and used hundreds of children as soldiers. She told me how she looked into this man’s empty eyes, put her hand on his arm and said in a firm voice, “Give me the children.” He refused and grew irate. She kept looking him directly in the eyes, kept her hand on his arm and said with all the authority of a mother to a wayward son: “You must give me the children.” She saw him flinch and then he turned to his men and said, “Let her take the children.” And she walked out of the camp with the children.

Living in London and visiting Berlin with sons Elliot and Nate in 1990 shortly after the Berlin Wall fell and Germany reunited.

The mother we celebrate on Mothers’ Day around the world is strong, loving, smart. Her children are primary for her care and affection. She helps them develop into caring, thoughtful adults.

As a mother I have tried to do that with my children, and as a daughter I had a mother who did just that. She saw my needs sometimes before I did, helped me grow and learn what I needed to learn, and then she had the wisdom to urge me to take what talents I had into the world, and she urged me to see the world.

When I was a girl, I used to go to the flight deck of the Love Field Airport in Dallas, Texas to watch the planes take off with my mother and sister. My mother hadn’t traveled much in her life, but she knew the world was out there, and she urged me to be part of it. “Where do you think that plane is going?” she would ask, and we would let our imaginations go. At least half of the destinations we determined were New York City, where I eventually lived, as well as in Baltimore, Boston, Los Angeles, London and Washington, DC. Because of work, I’ve had the opportunity to travel and work on every continent except Antarctica, a geography my mother would have enjoyed, at least in theory.

I once complained to my mother, “You never criticize me!” How is that for a complaint though it wasn’t entirely true. Her answer I still remember: “Don’t worry. The world will do that.” She saw her role to support, encourage and see the best in me so that I might see and become the best I could be.

I know not everyone may have had that kind of mother. In fact, my sister and I offer different versions of our mother. We are both mothers ourselves now. We try as mothers do, though never quite succeed, to cherish and guide and then let go of our children so that they might flourish as their best selves in the world.

Nashville: Facing the Wind

In the wake of recent events in the Tennessee General Assembly which expelled two African American lawmakers for their role in an unorthodox protest calling for more gun control after deadly school shootings in Nashville, I wanted to share my short story “The Beginning of Violence.” The story is set at the first sit-in in Nashville in 1960 and was published in my short story collection No Marble Angels. It was republished in Short Stories of the Civil Rights Movement: An Anthology (ed. Margaret Earley Whitt, University of Georgia Press, 2006.). The anthology includes 23 short stories by black and white writers—stories of the heart, not just politics—an historic journey we continue to travel.

THE BEGINNING OF VIOLENCE

by Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Nashville, 1960

The wind shot through you that day like fate or some might say like the will of God. No matter what you did, it got you. It weaseled under the buttons of your coat, pulled off your scarf. You couldn’t fight against it though you could stay indoors, but once you came out, you had to face the wind and find your way.

It was the day before Valentine’s, and snow was falling in thick wet flakes, had been since early morning and threatened to keep on all afternoon. As I said, it was not a day to be outside, but I was. I was downtown on the arcade doing last minute shopping for a sorority party that night. We’d been decorating all morning, but we’d run out of crepe paper and balloons; and Janie, the food chairman, was afraid she’d run out of paper plates and cups so I said I’d go downtown and pick up everything.

I went to Woolworth’s. At the Grand Ole Opry counter I bought a red plastic guitar set inside a big red plastic heart for the centerpiece on the officer’s table. I was an officer. I was treasurer of the Kappa Alpha Thetas at Vanderbilt University.

I didn’t feel like turning right around and going back into the cold so I stopped at the lunch counter for coffee and a grilled cheese sandwich. I was sitting there eating and reading “When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d” for English class when a blast of air swept across my back. When I turned to see who was holding the door open, I saw dozens of Negroes coming into the store.

They moved straight down the aisles then disappeared among the cheap jewelry and face powders and school supplies.

I turned back around and finished my sandwich and Whitman’s poem. I was about to pay and leave when three Negroes sat down at the counter, one of them next to me. They all held brown paper bags with purchases they’d made. The girl beside me smiled, showing a curve of white teeth and asking more than most people thought she had a right to ask. I looked over my shoulder and saw thirty or forty more Negroes lining up to sit at the counter.

It took me a minute to understand what was happening. I’d grown up in Arkansas and Tennessee, and in nineteen years I’d never eaten beside a Negro. I’d never sat next to one on a bus or gone to the same bathroom. Things were changing in the South, but these were facts I’d lived with. Once in high school in Little Rock I’d signed a petition favoring integration, and that had almost gotten me thrown out of cheerleading. Some people thought anyone for the Negro was a Communist. I wasn’t a Communist; I just thought the Negro should have a chance. And yet even feeling that way, I wasn’t prepared to have the order of things put to question right where I was sitting.

The girl kept smiling. She had a soft mouth and big, dark eyes. Her hair was straightened, and she wore it like mine, in a pageboy with bangs. She was taller than me, and under her coat she looked strong. When she saw my poetry book on the counter, she reached into her pocket and took out a copy of the same book. I couldn’t help but feel she’d just drawn her gun. I glanced away. My eyes fell on her hands; they were the color of dry soil, large and muscular and deeply lined like an old woman’s.

I glanced at her friend next to her, but her friend’s eyes were flat and hard, and her mouth looked set to tell me her mind. It was this girl who got me moving again. I’d been about to pay and leave when they’d sat down. My purse was open on the counter, and I went on counting out the change. I closed my wallet and my purse; I gathered my bags, stood and left. The act of leaving wasn’t a decision so much as a resumption of the way I was already going.

Not till I was outside in the blowing snow, moving towards the bus did I think about what I’d done, not till I was getting on the bus did I hear the words of the waitress: “I’m sorry, we don’t serve coloreds here.” All the way back to Vanderbilt, and as I walked on campus through what by now was a small scale blizzard, I kept thinking about those words. At the party that night, dancing under the crepe paper streamers we’d draped from the ceiling to make a tent, I could still hear the words and see the face of the girl.

The next morning I read about what had happened at Woolworth’s on page ten of the Nashville Tennessean. Without knowing it, I’d been in the middle of Nashville’s first sit-in. I decided to write my own version of what I’d seen, and I turned it into the college paper. The paper ran the story under the headline: “At the Counter: A Student’s View.” The editor asked me to write on what happened next though no one knew what was going to happen next, but the editor thought something would. He told me I should stress the Vanderbilt angle. I wasn’t sure what the Vanderbilt angle was, but that’s the way I got involved. Before the year was over, I’d witnessed more than a dozen sit-ins.

The next time I saw the girl was two weeks later. In between, the snow had kept falling, making it one of the worst winters in Nashville’s history. During those days on the front pages of the Tennessean, Jack Parr was battling NBC over his contract with the Tonight Show while in Washington Lyndon Johnson battled for national civil rights legislation. A hundred miles away in Chattanooga fighting had broken out after sit-ins there. The Nashville sit-ins had stepped up but were still reported on the inside pages. So far no arrests had been made.

All week rumors had been going around that the largest sit-in ever would take place downtown Saturday. I decided to go. Jeff, my boyfriend, tried to argue me out of it then said he’d go with me, but he got sick after a fraternity party Friday night, and so I went by myself. No one at the sorority house could believe I would go, but I did.

When I got there, thousands of people were already on the arcade, and policemen lined the streets. Just after noon the first demonstrators showed up, including the girl. She was wearing the same oversized brown coat; on her head she wore a white crocheted cap. She walked with her head down, bowed against the wind. She didn’t look at anyone. Most of the protesters were students, and they were glancing around at the crowds on the sidewalk. But she stared straight ahead. She was so focused that she didn’t even answer her friend who spoke to her as they entered McClellan’s Variety Store.

I followed them inside. The lunch area was packed with people standing about waiting to see what would happen. The girl made her way through the crowd to a seat at the counter. One by one other students took stools under the faded pictures of salisbury steak, Irish stew, hamburger deluxe. A railing separated the eating area from the rest of the store, and the press stood behind it among hair nets and hair rollers; I took my place with the press.

A waitress approached the girl. “I’m sorry; we don’t serve coloreds here,” she said. “You’ll have to leave.”

“A cup of coffee, please,” the girl answered.

“I’m sorry, we don’t serve coloreds,” the waitress repeated.

“A cup of coffee.”

Half a dozen white teenagers stepped into the area and started catcalling. They picked out a white demonstrator sitting near the girl. “Nigger lover! Nigger lover!” they taunted. A man with a cigar began blowing smoke into the face of the girl and the other students. Several more teenagers moved in, bumping against the protesters, trying to knock them off their stools.

The students didn’t react. The girl pulled her poetry book from her pocket and opened it on the counter. She was starting to read when suddenly she let out a cry. I looked and saw a teenager squash his lighted cigarette on her back. I couldn’t tell if he’d actually burned her or only ruined her coat. She jerked around. She stared straight at the boy. She met his jeer with a question which again asked more than people were willing to have asked of them. Her look must have shaken him or touched something in him because he stepped away. His friends started lighting their cigarettes and pressing them out on the backs of other students, but the boy left the store. The exchange took only a moment, but in it I saw some possibility, some viewpoint I hadn’t considered before.

Before I could think about exactly what this was, however, someone shoved a white protester from his stool and began hitting him in the ribs. The man blowing cigar smoke laid a fist into the back of a black student. Other teenagers began pulling at the hair of the girls sitting at the counter. None of the demonstrators raised a hand to defend him. I saw in the faces of many, anger and a struggle not to fight back. But in the face of the girl I saw something else.

The police finally arrived, but only after the teenagers had run away. They told the protesters they had to leave because the store management had decided to mop the floor. When they refused, the police moved in, taking hold of the students one by one and escorting them into police vans waiting outside. The girl was arrested.

I followed the rest of the day’s events, including the beatings of several Negroes late in the afternoon at Woolworth’s where no police were around. Members of the press, including me, watched as a white teenager pulled a Negro protester from a chair and hit him again and again in the face spreading open his nose with a fist, bloodying both their skins with the same blood and as another white pushed a Negro student down a flight of stairs, sending his arms and legs clattering against the metal. None of the experienced press stepped in to stop what was happening; instead they stood recording the incidents so I did the same. Yet inside I was trembling as if someone had hit me, and I wanted to strike back. I didn’t know what to do with the violence I suddenly felt. I left the store.

I decided to meet the girl. I told the newspaper editor I wanted to write a profile of a demonstrator, and he agreed. I found out her name was Cynthia Davis. She was a senior at Fisk University. When I called her, she at first refused to be interviewed, said there were better people than herself, but I convinced her she was the one I wanted to talk to. She agreed to meet me at a diner near Fisk after classes Friday.

Fisk is only a few miles from Vanderbilt, but like most everyone else, I’d never been in the neighborhood let alone seen the campus. The streets around it were quiet and lined with trees and houses. The campus itself was much smaller than Vanderbilt’s and more run-down. It had one main walkway. On both sides of the walk were dorms and classrooms. I decided to go in just to look. I stayed only long enough to walk to the end of the path and back again, but in that time the world closed in around me. I was the only white person, at least the only one I saw, and I felt everyone staring at me.

When I reached the end of the walk, I read the sign in front of a huge Victorian Gothic building. I tried to concentrate on the fact that this was the first building of the university, the first in the country built to educate Negroes, but the truth is I was thinking only about myself and the color of my skin for all at once my skin seemed alive as if it were plugged in and glowing and separate from me. For a minute I couldn’t feel myself under it. To be suddenly separate from your body is scary. Everyone thinks you’re your body because that’s what they see only you know you’re not. I’ve heard of people coming back after dying, saying they’ve watched themselves from outside, watched everyone else watching their bodies while they knew that wasn’t them only they couldn’t make themselves heard. I don’t want to go on too much, but that’s what I felt: a separation I couldn’t make my way across. The space between me and my skin was like the space between me and the Negroes, and in it was a kind of panic and darkness I wanted to strike out against. For the first time I understood why separation was the beginning of violence.

I hurried back to the car I’d borrowed. I locked the doors and sat for a moment. Finally I started the engine and drove to the diner a few blocks away.

It was five o’clock, and only a handful of students were at the counter and in the booths. When I came in, they glanced up, and again I felt my skin starting to glow. Behind the counter the waitress stared at me. She had a thick ridge of brown hair and dull eyes. She was wiping the stained formica with a rag which she tossed in the sink behind her without taking her eyes off me.

At first I didn’t see Cynthia in any of the tall wooden booths. From the front of the restaurant I could see only the person sitting at the edge of the booth facing forward. But then on the hook of the last booth I spotted the rough brown coat. When I approached, I expected her to recognize me as the girl she’d sat beside in Woolworth’s, but instead I realized she too saw me only as the singular white person in the diner.

She was studying at the table. She wore a grey knit sweater and a white crocheted cap on her head. I’d never seen her without her coat. She was much thinner than I expected. Her shoulders were narrow and her neck quite slender. Again I noticed her hands; they seemed disproportionately large now.

“Cynthia Davis?” I asked.

She nodded.

I sat down and moved towards the wall. Immediately I was hidden from view of the other people. “Thank you for meeting with me.” She didn’t answer. I glanced at her books on the table, and tried to think of what to say. “Do you study here often?”

She nodded again, watching me without speaking. She didn’t seem hostile, only reserved. I’d wanted to meet her to find out where she came from and how she’d arrived at this point in her life. Yet as she stared at me without recognition, I realized I’d also come here to have her meet me and approve of me, and her failure to recognize my imperative made me falter.

I set right into the interview. I asked about her family. She was third in a family of six children from Fayette County, Tennessee. Her father was a preacher, a small plot farmer and owner of a modest dry goods store. Her mother worked the farm and raised the children. Cynthia would be the first of her family to graduate from college. At Fisk on a scholarship, she was an A-student, an English major, and she hoped to go on to law school next year.

She answered my questions without self-consciousness, and because she was at ease with herself, I began to feel more at ease. When I’d run through all the facts I wanted to know, I set my pad and pencil down. Leaning forward on the table, I fixed my eyes on the translucent lobes of her ears which supported the weight of heavy metal hoops. I stared at these as I tried to form the question I had come to pose. Finally I asked, “Why don’t you fight back? The other day, when that boy burned you, why did you just sit there?”

“He was bigger than me,” she answered.

I frowned.

“What would it have proved?”

“That he can’t get away with what he did.”

She smiled. “But he can. We both know that. Fighting him wouldn’t have changed anything.”

“How does getting beaten up or burned change anything?”

“It doesn’t.” She picked up a napkin from the table. She was quiet for a moment; then she asked, “You ever taken a hound dog hunting?” I smiled, surprised by the question. “When a hound dog gets a scent, he won’t let go. He doesn’t care if it’s raining or it’s getting dark or it’s time to go home to bed. You can beat him; you can pull his collar till you choke him, but if he’s got the scent, he’ll do everything he can to take it to the end. Our movement’s like that hound dog. We got the scent, and no one can beat it out of us or burn it out of us. The only thing they can do is show their own meanness.”

She began folding the napkin in her broad hands. Her expression was serious, yet the corners of her mouth turned up, almost smiling, as though she were extending tolerance not only to me but to herself. “We used to think the white man controlled our lives,” she said, “only since we can’t control the white man, we thought we had no control. But it doesn’t matter what white people say we are; it doesn’t matter what unjust laws say we have to do. We know who we are. First and foremost we are God’s children, and no one can turn us into hateful, beaten-down human beings; no one has that power. Power—that’s the scent. It comes from treating a man right. Once you understand that, it will change your life. Jesus Christ showed us how. Mahatma Ghandi showed the people of India they could do the same thing.”

As she spoke, her curious smile remained as if she understood the difficulty of her point of view. She spoke deliberately. She wasn’t carried away by her words but reasoned through to her conclusions with a logic as careful as any lawyer’s. “The righteousness of our cause will win over the hearts of good men and women and eventually change a whole system,” she insisted. She glanced down at the napkin which she’d shredded into a small mound of confetti. She swept the paper into the palm of her hand and dumped it in the ashtray.

“From what I’ve observed,” I offered cautiously, “your friends aren’t as free of the hate and anger as you. Perhaps you understand more.”

Her shoulders straightened against the back of the booth; her face roused. “Don’t try to separate us,” she warned. “You can’t choose among us. What I understand, we all understand.”

“I don’t think that’s true. Your friend next to you, both times I saw her, she was angry. She wanted to strike back; I saw it in her face. You didn’t. I understand what I saw in her; I don’t understand what I saw in you.”

“I’m angry. Anyone not angry is asleep. But we have to struggle with our own weaknesses as well as with society’s.”

“But if your movement depends on society having a conscience and that conscience stirring…well, frankly, I doubt how many good-hearted men and women you’re going to find.”

“Then that doubt is your weakness, isn’t it?” she offered.

I looked up. She stared at me with a calm, penetrating gaze which struck at that separation I’d felt on campus, first from myself then from others. I didn’t answer. Instead I began asking about her friends, again setting her apart from them. Again she held to the group, answering only in the plural. She emphasized she was committed to the Christian ethic of nonviolence for only as one was able to yield himself to God’s goodness was he able to express his own and see goodness in others. Yet as we talked now, I felt uneasy for she’d seen something in me which I hadn’t seen, yet which, when named, I knew: a doubt, a smallness of belief, a smallness of heart. I had wanted her to know me, but now I resented what she’d chosen to know. I found myself wanting to expose something in her.

We talked almost an hour as the diner started to fill with students. One by one the booths around us sounded with chatter. Cynthia was leaning closer to me so we could hear each other, her head propped between her ashen palms, her sweater pushed up above rough elbows. Finally as the interview wound down, circling around questions I’d already asked, the quick light in her eyes resumed a quieter glow and her half smile drew back into the reserved lines of a stranger’s.

I wrote my article for the paper the next week. It brought me immediate attention. I didn’t exactly glorify Cynthia Davis, but I set her up as an example of a generation of blacks with expectations to achieve beyond their parents and with a commitment to American ideals of equality. In writing it, I forgot for the moment my own discomfort over what she’d seen in me, and I wrote in an inflated prose that would touch the sentimental strain in a white, liberal audience. I also told the story of a girl’s ambitions which would offend those of a different persuasion. In the article I mentioned only that Cynthia’s family lived in Fayette County.

The next week a reporter for the Nashville Tennessean called me to ask if the Tennessean could run my story as a side piece with a larger article they were doing on inter-college contact in the civil rights movement. The reporter was particularly interested in the fact that I’d gone over to Fisk to have the interview.

I agreed. It would be my first paid article. Because the audience of the Tennessean was statewide, the editor wanted to know exactly where Cynthia’s family lived, and so I gave him the town’s name just outside of Memphis, and he printed it.

I thought of calling Cynthia and telling her about the story, but I didn’t. I suppose I was afraid she’d object. I was also in the middle of mid-terms. I finally did call her Sunday, the day the article appeared. I phoned that afternoon, but she wasn’t in. I left a message for her to call me back and then forgot about her. For the next few days friends and people I hardly knew stopped to talk about the story. They didn’t talk so much about what it said as the fact I’d had it published in the Tennessean. Finally on Wednesday when I hadn’t heard from Cynthia, I called again, and this time a friend of hers got on the phone.

“Cynthia’s not here,” she said. The friend’s voice was strained, but matter-of-fact. “Her father’s store was bombed Sunday night. Her brother’s in the hospital. I don’t know when she’ll be back.” Her friend didn’t say anything about the article. I didn’t know if she or Cynthia had even seen the article. I couldn’t be sure the bombing was a result of the article.

I didn’t see Cynthia Davis again. I phoned her several times, but she was never there. Then school got busy. I was starting to write freelance for the Tennessean, and I quit calling. At one of the sit-ins that spring I saw her friend, whom I recognized from that first day at Woolworth’s, and I went over to her. She answered my questions formally. She told me Cynthia had taken a leave from Fisk to help at home and in the store until her brother got out of the hospital. She told me nobody knew how long that would be or how her brother would adjust for among his injuries, his right hand had been blown off.

The Nashville sit-ins kept on through the spring. There were more arrests, more beatings of Negroes, negotiations with white business and political leaders, a cessation of arrests and sit-ins during negotiations, an economic boycott of downtown stores, a bombing of a black lawyer’s home. But finally on May 10, less than three months after the first sit-in, an agreement was announced. Six downtown lunch counters would open on an “unbiased basis.” The victory was the first of many to follow in Nashville. In the annals of southern history in the early 1960’s, the Nashville movement was considered a nonviolent success story. Cynthia Davis was not among the names who moved onto prominence out of that movement. To my knowledge, she never returned to Fisk.

I’ve thought about Cynthia Davis from time to time since then. Once the following fall on the way back to school, I drove through Memphis with the intention of going to see her, but I lost courage. To be honest, I didn’t want an answer. If there was an answer. I didn’t want to be told that what happened was my fault. In some ways I was sure it was; and yet in others, no matter what anyone said, I wouldn’t accept the blame. I didn’t know what to do with it, and I didn’t see how having it helped anyone.

I changed because of what happened in small, slow ways. By the spring of my junior year, I’d dropped out of my sorority. I became wary of my own ambition. I began to regard it as a subtle, unpredictable beast which, if I was not alert, would bite with sharp teeth.

When I think about what happened now, I account it to the wind. To what happens because of all that’s happened before for reasons you don’t understand because you’re in the middle of them and because you don’t understand yourself. I don’t account it to fate or the will of God or any other cosmic design. I account it to my ignorance of design. And as I said, to the wind. I let the flow take me with it because I hadn’t learned to face the wind, to pick up the scent but not be blown about. Because I didn’t heed dark, unexposed places in myself, I fell inside one of them and perhaps took another with me.

The Manuscript in the Drawer

The Manuscript in the Drawer

by Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

published by The Hopkins Review

I’m sitting at a bar sipping club soda and writing. I’ve discovered this corner of a Washington, DC restaurant that has a long bar with plugs underneath for my computer. If I sit at the very end, I can occupy two or three seats—one for me, the others for my work—without inconveniencing anyone. I order soup or a cheese board, drink soda or a cappuccino and write for hours with the hum of trivial and sometimes consequential conversation around me, but not addressed to me. The clientele ranges from college students to government officials. I can eavesdrop, not to gather anyone’s business or secrets but rather the rhythm of life and conversation while I write from my own thoughts and imagination.

Before the pandemic, this was my modus operandi for decades, writing in restaurants. I began my career in a newsroom. Once when asked my ideal writing environment, I answered without thinking, “In the middle of a newsroom where I’m left alone to write fiction.” I like the hum; it concentrates my mind. At the moment three coeds a few stools away are bubbling over the boys and boyfriends in their lives. The conversation seems ephemeral and young to me but important to them. I remember that focus, though I think I was in junior high school then.

In these various venues, I have written four novels. Two of these are at last getting published, one in March 2023, the other spring 2024, demonstrating that writers write and eventually publishers publish. Burning Distance and The Far Side of the Desert are being published with a promotional tag suggesting “Jane Austen meets John LeCarré.”

In these various venues, I have written four novels. Two of these are at last getting published, one in March 2023, the other spring 2024, demonstrating that writers write and eventually publishers publish. Burning Distance and The Far Side of the Desert are being published with a promotional tag suggesting “Jane Austen meets John LeCarré.”

I’ve been writing a long time, beginning as a journalist then shifting to fiction. In the late 1980s I published a collection of short stories—No Marble Angels—then a regional best-selling novel—The Dark Path to the River. Then came a long hiatus in publishing fiction. I suspect I am not the exception but rather part of a large family of writers whose novels may not be immediately published but who continue writing because sorting and organizing life and experience through words and stories is what we do.

Anatole Broyard, famed New York Times columnist and literary critic a generation ago, noted the value of the manuscript in the drawer. By writing you were helping order the universe, he claimed, staying faithful to the task of thinking and seeking harmonies in the world. I often shared his column when I taught writing. It resonated with me and always with my students.

The value of the manuscript in the drawer expands when it finally gets out of the drawer and into the universe. Burning Distance, released this spring by Oceanview Publishing, might have been prescient if published when first written. It is a love story between an American girl and Lebanese/Palestinian boy who meet at the American School in London before the first Gulf War and whose parents turn out to be connected to arms trading and the weapons smuggling that fueled the war and the years that followed. The novel spans 1981–1996. Now it may be read as historical fiction.

Living in London at the time, I was able to do extensive research and interviews after the first Gulf War. Along with others, I recognized the detritus of weapons, including those of mass destruction, left behind and accumulated in the build-up to the war and learned of the complicity of Western suppliers in that process. With children at the American School in London, I also witnessed how their generation was relating and developing friendships across national, political, and religious barriers and offered the possibility of a more connected world.

Among my ten-year-old son’s friends at the time were the son of the Kuwaiti Ambassador and a student from Iraq. When I picked my son up at camp the summer of 1990 and told him about Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, his first question was: What will happen to Talal and Alec? The Kuwaiti friend began to travel with bodyguards, and the Iraqi friend never returned to the American School. The personal and political intertwined in my imagination, and the seeds of Burning Distance were planted.

I did extensive research. Through journalist colleagues who traveled and covered the Middle East, I was able to interview individuals, including an ex-director of one of Saddam Hussein’s ministries crucial to the acquisition of nuclear components. When Saddam insisted he work to develop an atom bomb, the man refused. Saddam put him in prison. During the chaos of the war, he managed to escape to Iran and eventually made his way to England.

The challenge for me as a novelist was to take all the research and massage it into story and literary language, masticating “long-range ballistic missiles” and “isopropyl methylethylphosponoflourodite” into story and the language of literature. Sometimes the book seemed larger than my experience and skill as a writer, and yet I couldn’t put it down. Between drafts I wrote short stories, articles, and two other novels, then I came back again, fresh, ready to reenter the lives of my characters and live through another and then another draft. Time has passed, but the themes remain relevant.

“Burning Distance is a double helix of a book, carefully plotted and beautifully told,” novelist and Washington Post columnist David Ignatius has offered. “It’s a spy story interwoven with a love story, and the strands fit together in a way that moves the reader effortlessly from chapter to chapter. While fiction, its narrative of the CIA and the Middle East arms trade are very close to fact.”

Writers have been generous in their early response. After writing, the affirmation of readers is one of the payoffs, though the process of writing remains the gold.

My son Elliot Ackerman, the friend of Talal and Alec, is now himself a novelist and journalist. He once dubbed me “the last of the paper generation.” He was right. My basement is filled with research files and drafts of manuscripts. Somewhere among these is Anatole Broyard’s essay which I haven’t been able to find in my files, but its sentiment and the value of the manuscript in the drawer abides.

Burning Distance—The Daughter of Jesse West

Umbrellas snap open like a flock of blackbirds arriving at the grave. Twelve of us stand wing to wing as clouds roll over the green hills and the rain falls harder. Few families endure one murder. I am mourning the second in my lifetime. I’m nineteen years old, and I am beginning to see that life connects.

My father used to say, “There are no coincidences, only life showing you its patterns.”

As I watch our small gathering on the hillside, I strain to see the pattern….

So begins my new novel Burning Distance which publishes on March 7 and can be ordered now. The opening chapter of the novel and an essay “Manuscript in the Drawer” will also appear on pub day in The Hopkins Review online.

So begins my new novel Burning Distance which publishes on March 7 and can be ordered now. The opening chapter of the novel and an essay “Manuscript in the Drawer” will also appear on pub day in The Hopkins Review online.

I hope you’ll enjoy the story—find it moving, entertaining, informative, surprising…

I leave the adjectives to readers who I hope will also take a moment to write a comment or review with online booksellers if that is how you order. These are used to offer extra promotional benefits for the book. They also help the book on its way.

Burning Distance took years to research and write and even longer to publish. You may find of interest the Author’s Note at the end of the book which shares some of that journey and history. The publisher through Goodreads promoted Burning Distance this month with some giveaways of the digital book.

While the facts are well-researched for Burning Distance, the characters, the story and the world created sprang from imagination. The novel’s promotional copy heralds the novel: “Jane Austen meets John le Carré in this cross-cultural love story and political thriller….A modern-day Romeo and Juliet set against a background of arms smuggling in the Middle East.” I hope the book will appeal to readers who like international political thrillers and also those who enjoy a love story and family drama with characters you can care about.

I hope you will come along on the journey of Burning Distance. If you find yourself engaged, please tell a friend or many friends. A book extends its life through its readers and expands that life through word of mouth. Let me know what you think. And make some noise!

Thank you in advance,

Joanne

Events and appearances will be posted on the Speaking page of this website. I love to speak and meet with readers. Requests for appearances, zoom meetings or book club discussions can be noted under Contact Info.

Waiting for Spring

The winter solstice has passed, and each day adds two to three minutes of daylight.

The crocus buds have already broken through the soil. So far winter in the mid-Atlantic, at least in Maryland and Washington, DC, has been wet but not freezing though we are not yet safe from frost. I wish the buds would hold off, not be too anxious to pop above the ground. February can still be a fierce month.

In the garden the birds are clustered around the bird feeder for food which is still scarce on the trees. The squirrels have figured out how to tip the feeders and scatter the seeds and grain on the ground so they can run off with it. My dog spends hours at the window watching the squirrels, just waiting to get out to defend her turf. She’s taken the side of the birds which she also watches but allows with more tolerance in her corner of the garden.

She sees a fox and wants to chase after it though she is smaller but just as fast. It is mating season for the foxes, and they disappear into their den.

The early signs of spring are breaking out everywhere. We wait, not always patiently, for the earth to warm, the flowers to bloom, the cubs to emerge and disappear into the woods and for the earth to tilt towards the sun.

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Lights in a Dark Season

The winter holidays start with lights in the U.S. and in many countries around the world. In the U.S. the lights begin to appear in early November, shining on street corners, in department store windows. By the end of November and the U.S. Thanksgiving, holiday lights are up and twinkling in white, blue, red, green, and gold on city streets and on country roads. By early December the lights are entwined on the trees and strung around front porches and lawns, and in shop windows, challenging the onslaught of winter’s darkness and the somber journey to the shadowed side of the sun.

The tradition of lights on Christmas trees started in 17th century Germany where they were attached by wax or pins. Then along came Thomas Edison and the electric light. By the late 19th century—in 1882—Edison’s friend and partner Edward H. Johnson developed the first string of electric lights for a Christmas tree by hand-wiring 80 red, white, and blue light bulbs together and winding them around his tree.

Many holidays around the world celebrate with lights, especially in the winter months, not only Christmas, also Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, Diwali, St. Lucia Day, the Winter Solstice.

At a time when war is taking away the option of lighted cities, let alone festive lights for many in the Ukraine and elsewhere, I wanted to share these virtual lights with a wish for illumination in the year ahead.

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Birds, Books, and the Sky Above…

The geese have returned, flying in from Canada as the weather turns colder up north. The honking above each morning and evening signals the changing seasons.

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

As autumn accelerates with in-person meetings and events in Washington and New York, many for the first time in almost three years, I’ve been away from this haven on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. But I have now arrived back for a few days, and in the morning quiet before the birds awake, my eyes and thoughts are drawn to the water and sky and larger vistas.

This coming spring 2023 I have a new novel coming out and anticipate going on the road a bit. During the pandemic my two nonfiction books published were limited to zoom calls and meetings. I’ll be glad to get out to meet readers again. Burning Distance, my first novel published in many years with a second novel—The Far Side of the Desert—coming out in 2024, moves into new territory. A thriller/mystery/love story set between 1981-1996, Burning Distance’s promo copy heralds: “Jane Austen meets John le Carré in this cross-cultural love story and political thriller. A modern Romeo and Juliet set in…the dark world of arms trafficking.”

The novel took years of research and writing. Like many writers, I write even if not immediately published just as artists paint or musicians make music. I have several novels at the ready, and the gate is finally opening. I hope you’ll step through it with me and enjoy.

I’m sharing here the cover of Burning Distance and some of the generous responses from writers who have read the novel. The book officially comes out March 7 but can be preordered on links here. I hope you’ll order, read and share with friends. Friend-to-friend, reader-to-reader word of mouth is how writing finds its home. Thank you in advance for your support.

“Burning Distance is a double helix of a book, carefully plotted and beautifully told. It’s a spy story interwoven with a love story, and the strands fit together in a way that moves the reader effortlessly from chapter to chapter. While fiction, its narrative of the CIA and the Middle East arms trade are very close to fact. Joanne Leedom-Ackerman observes the world of American spies and Arab fixers through the eyes of a young woman who keeps asking questions about her mysterious past until she gets all the revelatory answers. A subtle and satisfying novel.”—David Ignatius, New York Times best-selling author, Washington Post columnist and novelist

“Burning Distance is a double helix of a book, carefully plotted and beautifully told. It’s a spy story interwoven with a love story, and the strands fit together in a way that moves the reader effortlessly from chapter to chapter. While fiction, its narrative of the CIA and the Middle East arms trade are very close to fact. Joanne Leedom-Ackerman observes the world of American spies and Arab fixers through the eyes of a young woman who keeps asking questions about her mysterious past until she gets all the revelatory answers. A subtle and satisfying novel.”—David Ignatius, New York Times best-selling author, Washington Post columnist and novelist

“Burning Distance opens with a mystery, glides into a love story, and unfolds into a political thriller. Set against the backdrop of 1980s and 90s global politics, readers will be up way past their bedtimes eagerly turning pages to discover what happens to Lizzy and Adil. A story of war, family, history, politics, and passion. Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’s evocation of the era is pitch-perfect. A great read!”—Susan Isaacs, New York Times best-selling author of It Takes One To Know One

“Running the gamut of emotions from fear to love, this plot surges along as unpredictable as a riptide. Romance and thriller readers will both find plenty of mischief and mayhem.”—Steve Berry, New York Times best-selling author of The Omega Factor

“I entered the world of Burning Distance—of the characters Lizzy and Jane and Sophie and their mother and the family of Winston, Pickles and Dennis and the world of Adil Hasan and his father—and I didn’t want to leave. I cared what happened to them and was pulled along without being able to stop until the book was over, and even then I didn’t want to leave. The narrative voice unfolds the story both poetically and realistically. The story it tells is also the story of a political and historical time (1981-1996) that is relevant to the times we are living through. The narrative opens for the reader some of the history that has taken us to the current events in the Middle East and Europe and America. But first and foremost the reader will want to read Burning Distance to know the characters, particularly Lizzy as she makes her way and follows her heart through the conflicts of history and culture and family to find ‘the music’ that is in her life.”—Azar Nafisi, author of Reading Lolita in Tehran

“Lizzy is ten when her father’s plane explodes over the Persian Gulf and her life is set in motion. In the background of the narrative is the Gulf War and in Lizzy’s life, her father’s death marks the beginning of a search to peel away secrets, betrayals, international intrigue, dangerous associations which bring all the characters in this book under one umbrella. Burning Distance is a mystery, a complicated, story-driven drama of lives lived amidst the high risk of life and death in international arms trading and the book is grounded by the unlikely love story between Lizzy and Adil Hasan. Her obsession is to uncover the secrets which led to her father’s death and in her quest she comes to find that everyone in this story is linked by danger, everyone is at risk. This is a real page turner which also informs, excites and moves us.”—Susan Richards Shreve, author of More News Tomorrow

“I was immediately engrossed in the lives of Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’s characters and their fascinating and compelling stories. Joanne has the ability to take the big issues of contemporary life (including the clash of cultures and a remarkable grasp of the weapons trade) and render them in the contexts of love, conscience, and the consequence of choice. She reminds us as did Donne that we each are a piece of the continent, a part of the whole of humanity, and that no matter how difficult the time, that love and peace and hope can be realities rather than abstracts.”—Eric Lax, author of Faith Interrupted

Clouds Have Lifted…Leave the Balcony Open

The clouds have finally lifted after days of grey and rainy skies. The sun is rising in all its quiet splendor. I can see light hovering at the horizon on the far shore this early morning.

Photo Credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Since I returned from PEN International’s World Congress in Sweden earlier this week, the landscape here has been shrouded with the outer edges of Hurricane Ian. As the storm moved up the eastern coast of the United States, it delivered rain and wind and grey skies to the Washington and Maryland area. We are fortunate and probably needed the rain, but the devastation of the hurricane to the South haunts us and fills the airwaves with troubling news and pictures, as it also does regarding the war in Ukraine, the protests in Iran, and the famine in Somalia. These remind me to be grateful for my cloud-enshrouded patch of earth and at the same time to be attentive to all that lies beyond. My patch of earth at least is now filled with light.

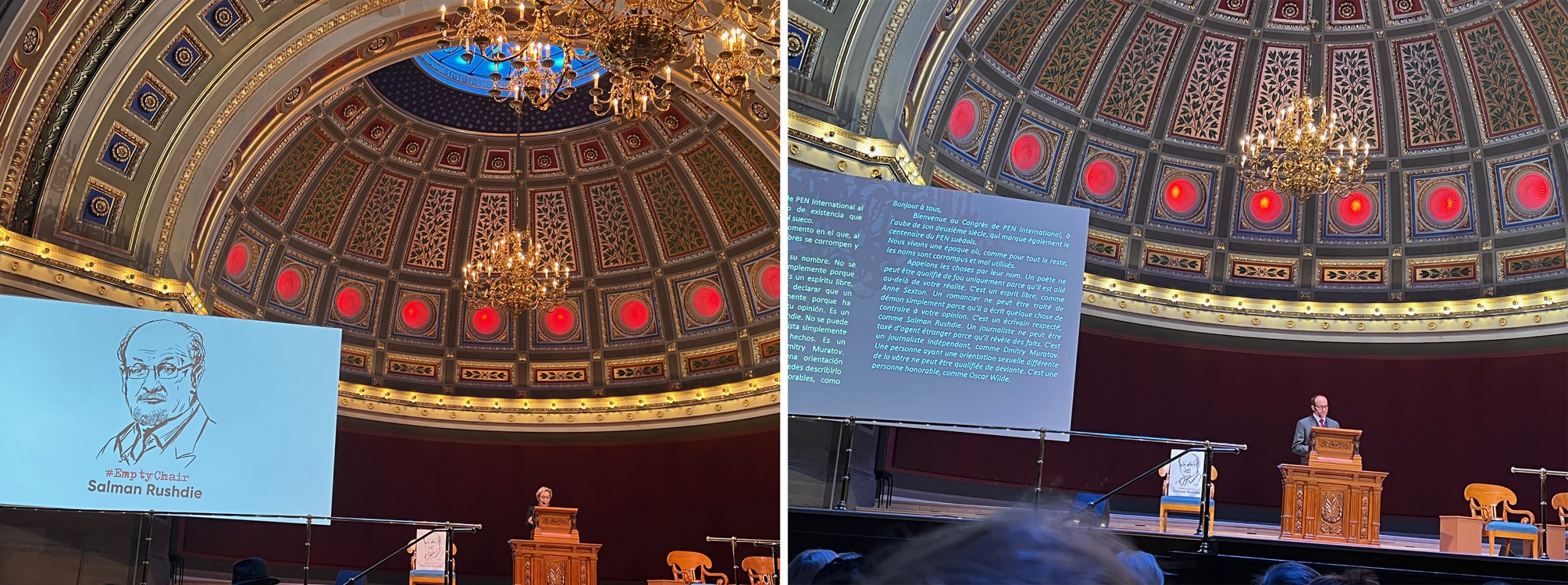

Connected as we are and as we were this past week in Uppsala, Sweden at the PEN International Congress, we were reminded of the origins of the 101-year-old organization PEN, begun in the aftermath of World War One’s devastation. A few British writers, including Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy, who later won the Nobel Prize for Literature, came together to form a dining club for writers of different countries in the hope that a community of fellowship and understanding would arise and diminish the nationalism and tensions that had brought on the First World War. Soon the concept spread across Europe and North America and then Asia, Africa, South America, and the Middle East. The mission also expanded to defend writers under threat. There are now 150+ centers of PEN in over 100 countries.

88th PEN Congress, 2022, Uppsala, Sweden. Photo credit: Gustav Larsson

After two years of meeting on zoom, PEN delegates from 100 centers came together, hosted by Swedish PEN, to celebrate and defend literature, translations, and freedom of expression around the world, to bring to bear a collective voice to combat threats to writers and also to see longtime colleagues and friends. Gathering around the theme “The Power of Words,” writers celebrated the multiple languages and literatures represented and also strategized to defend writers arrested, disappeared, and killed by authoritarian regimes.

“PEN has power but not power to prevent some writers getting killed,” said International PEN President Burhan Sönmez. “But we won’t leave people of art in the hands of dictators.”

Opening Ceremony at PEN International World Congress in Uppsala Sweden: Romana Cacchioli, Executive Director PEN International (left); Burhan Sönmez, President PEN International (right), Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

The bid for fellowship and a collective voice to protect writers under threat continues to inform PEN’s work a century after its founding. The 88th PEN World Congress sent its members back across the globe to work. The poem “Fairwell” by Federico García Lorca, read by PEN’s International President, went with us:

“Fairwell

If I die,

leave the balcony open.

The little boy is eating oranges.

(From my balcony I can see him.)

The reaper is harvesting the wheat.

(From my balcony I can hear him.)

If I die,

leave the balcony open!”

The Summer Sky…

I keep taking pictures of the sky and its changing scenery. I don’t need to go anywhere to travel its corridors of beauty and drama though as the summer ends, I will be on the road more often, and the sky will more often turn gray and the drama on the ground more compelling.

But on this last week of summer, this first weekend of September, I share the sky and its vistas, the sun rising and setting, and hope the perspective inspires days ahead.

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman