Blog

Time and Tides: Destroying and Building in Washington with “No One To Talk To”

The sun is rising but hiding. I know the sun is there by its effect, by light shining up on the clouds above, even though I can’t see the sun.

It is mid-January in Florida, and I’m sitting fully dressed in the sand by the ocean at high tide on a chilly day. The ocean rolls closer and closer to me on the wet sand. When should I move? I’m testing the tides. Can I hold my ground, or do I have the instinct & wisdom to know when to retreat to higher ground?

I went south for a few days in January just to remember warm weather and sun, only it was cold & rainy most of the week. But I was productive sitting in one place for hours writing on a new book—12,000 words in a week—words that need reshaping and editing but I also edited them each day.

Finally on my last day the sun appeared. The temperature rose a bit, and I could sit outside in the morning in a sweatshirt and not freeze as I watched the sun battle its way through the clouds, only the sun wasn’t doing the battle. It was there shining, always there. It was the clouds hanging over it I had to see through, look for the effect of the sun shining upward, lighting the patches of sky which the clouds weren’t covering, illumining the edges of the clouds themselves with a fringe of pink and golden light.

Oops…it’s time to get up as that last wave touched the top of my toes and the clouds settled in again over the face of the sun.

Back on the Eastern shore of Maryland, mid-February: I wake early along with the birds which share their song on the river. The stars are disappearing from view as the sky grows light and turns a pale grey. The river is as still as glass this morning. Land, water, wildlife appear to be waiting for the dawn and for spring. New birth, hope, promise are in the morning air in spite of fraught affairs on the ground.

Just 80 miles away in Washington, DC the world feels as if it’s fracturing. In the bitter cold and crackling atmosphere plants still lie dead in winter and appear unmoved by the possibility of spring. Here government buildings are losing their signage even before such acts are rendered legal. USAID which provides aid and services for hundreds of thousands abroad who are in need of food and shelter is being shuttered even before the closing down is sanctioned by courts or Congress. The magnificent US Institute of Peace which was created by an Act of Congress as a nonpartisan space with a mandate to provide tools and activities around the globe that lead to peace-building among combative factions in nations has been put on a list for closure, but it was Congress, not the executive, that sanctioned it. The post office itself which was created as an independent agency is reported soon to be shuttered in my own neighborhood and turned over to whom? The Kennedy Center, a hub of the arts—drama, opera, music—in Washington, again a nonpartisan space, not created for partisan players has been handed over to the administration, to a President who was not elected with a majority—just 49.9% of the vote. Unelected, unvetted individuals are attempting to shut down whole offices and letting go hundreds of thousands of workers without process or evaluations and reportedly assigning tasks (and contracts worth billions) to the one shutting them down, contracts never opened to bidding.

A worker removes the U.S. Agency for International Development sign on their headquarters on February 07, 2025 in Washington, DC. Photo by Kayla Bartkowski/Getty Images

A pile of building letters are seen after a worker removed the U.S. Agency for International Development sign on their headquarters on February 07, 2025 in Washington, DC. Photo by Kayla Bartkowski/Getty Images

Over the last weeks, I have been on numerous calls with nongovernmental humanitarian organizations, human rights organizations, United Nation organization, all struggling to figure out what these shutdowns of funds and people will mean for their future.

“The call about the Stop-the-Work orders was cancelled because of the Stop-the-Work order,” one individual reported ruefully. “We called for clarification but there was no one there to talk to.” “There were no metrics, no standards or criteria offered about how decisions would be made on resuming funding or returning personnel,” several people reported.

I have spent my years in what I’ve considered a relatively nonpartisan space even though I live in Washington. Beginning my career as a journalist, I believed and continue to believe it is important to have individuals who are “fair brokers”—not beholden to any political party. I have rarely contributed to political parties or campaigns; I contribute to issues. I vote, but I don’t campaign for specific candidates or parties. I try to see value in each and to provide a bridge for ideas. I have a point of view, but my view and judgement are not beholden nor am I trying to drive it. I haven’t joined a party though I appreciate and respect those who do. There are issues I think/hope are beyond party—education and human rights to name two. For decades foreign policy has been a space where the two parties could at least agree on what was the national interest even if disagreeing on the path to get there. They agreed about the importance of protecting the US and other countries’ freedoms—freedom of expression and freedom to choose.

Soon we will welcome warmer weather, extended sunlight, and the daffodils of spring, but I am deeply worried about the body politic and the direction of my country in a way I haven’t been during my lifetime. For much of this period, America has been—if not always the beacon on the hill—at least a safe harbor, a place where those living without the rights of the individual protected and respected, could look to and be assured of moral support, assistance, and sometimes refuge.

I have warned others not to let fear drive the discourse or agenda these days lest we fulfill our own fears. As I end this blog, I warn myself the same. One by one we will need to find what we can do well and do it, whether it is writing, sharing ideas, donating to causes or helping a neighbor. One by one we will need to dissolve, or at least curb, fear by actions that embrace and care and continue believing and acting to advance a “shared world.”

On the calls and in the meetings with the nonprofits and UN agency, I’ve listened to individuals who are mobilizing to address this new world, to find ways to keep services alive. Few spend time remonstrating. Instead, they are addressing what can be done and looking for answers. Those individuals who are driven by retribution are looking backwards. Retribution is a misshaped tool that tries to punish the past and shape the future with a hammer rather than with a scalpel and imagination. An architect and builder can plan and build a future, but that is not what we are seeing at work. To paraphrase the wisdom of others: It takes little time to destroy but years and centuries to build.

Going South…

I’m heading South for a few days. The frozen river in front of me has melted, the ducks are swimming again, but sub-freezing temperatures and ice and snow are returning tomorrow, and hunters are still out till the end of January.

I want to think in the sun, or at least in warmer weather for a few days, so I’ll leave the day before Martin Luther King’s birthday and the Inauguration. I’ll visit family and write from a place with sun and sea gulls and add to this blog there.

I would like to ship our snow and ice to Los Angeles where I lived for 11 years. I recognize with deep sadness and memory the places now destroyed by fire. The landscape is compared to the ruins in a war zone. This is accurate. An important distinction is that no enemy did this, and communities are helping each other and trying to save each other and the animals. This spirit of community and caring for one’s neighbors is prevailing.

From afar friends and neighbors can help with aid. (Some sites for donations are listed at the end of this blog.) Extending and expanding compassion wherever we live helps that spirit. Community is not partisan. Outreach is not what can you give me if I give to you, but an expression of shared humanity.

I’m sitting outside with freezing fingers tapping on my phone in the cold dawn of the Eastern Shore of Maryland. It is time to go inside. I’ll finish this blog in warmer climes….

Clouds envelop the sky today on the warmer shores of Florida. It’s raining, but I’m no longer bundled in mittens and socks and boots. Ideas and words continue to flow so I can sit by the window, glimpse the ocean in the near distance and write all day. While I don’t see the sea gulls at the moment, I know they’ll return. A crow is hopping outside on the railing. I like crows; I’m reading and writing a bit about crows, but that is for another day. Back to you in March….

Some suggested sites for donations of aid and books to writers and libraries and schools in the Los Angeles fires:

PEN America Los Angeles Wildfire Emergency Response Grant

LA Fire Department Foundation

California Fire Foundation

Wildfire Recovery Fund – California Community Foundation

Dream Center

World Central Kitchen

Los Angeles Regional Food Bank

American Red Cross

Save the Children

Donate new and gently used books (Adult Fiction and Non-fiction, YA, Middle Grade Novels, Fantasy, Speculative, Sci-Fi, and Children’s picture books)

Contact @juliafierro or @LAWildfireBookDrive for details

Morning on the River: Squawking into the New Year

And Then They Said…

Ducks and geese are on the river this morning swimming south to north, squawking and talking to each other all at the same time and to their friends across the water. It is cold, though not quite freezing. I wonder why they haven’t yet taken off for warmer climes. By the time I share this blog in early January, they may have left, though some will stay all winter and consider the Eastern Shore of Maryland their seasonal south.

When spring comes, the ducks and geese will fly north to spend summer months in Canada or wherever they go. But it is reassuring that they are still here so that when I wake before dawn, bundle up and sit outside to watch the sun rise, I can also watch them swim by. As light slowly lifts the darkness, before the sun ascends between the trees across the river, the geese and ducks begin their conversations.

I wonder what they say. I am certain they are not talking about my country’s politics either mournfully, exultantly, or resignedly. The President and cabinet of the U.S. government has no meaning or reference to them any more than the emphatic cause of their noisy conversation does to me though we exist together on this cold and beautiful morning. But I do learn from them and pause to watch and listen. I learn, or re-learn, that the universe is broad and complex, that there are points of view I don’t comprehend, that the governing power of us all is far greater than national politics and, I believe, more benign than we comprehend, distracted as we get by our insistent points of view.

I long for, and acknowledge a bit of a utopian point of view, that we might recognize the best in each other and allow that to develop without battle and retribution. I also acknowledge that this is not the way the human species always behaves, at least at this moment.

Yet it is worth taking a moment at the start of the new year to lift the gaze, appreciate the rising sun, the course of ducks and geese and other creatures we share this planet with, to listen in that moment in order to see and hear a larger wisdom which can inspire. Whether that inspiration dawns today or another, I feel certain that it is there and that the world around us will proceed. The sun will rise and set. The river will flow out to sea and the ducks and geese will keep talking.

Suddenly there is a stir, a burst of noise moving closer, almost like a giant machine approaching. At least a hundred geese fly towards the shoreline squawking and talking and settling on the water right in front of my house, almost as if they know I am writing about them and they have more to say, or perhaps they have figured out that here is a safe place because hunters aren’t allowed, and hunting season has begun. In James Michener’s novel Chesapeake he noted that the ducks and geese learn over time where the safe places are and communicate with each other…perhaps a “kinship with all life” and go there. In any case, the finale to these morning thoughts is a cacophony (or is it a symphony?) of geese and ducks on the river in front of me, though if they venture up on the lawn, my fearless small dog will bark and chase them back into the water. That is her conversation and contribution. They will squawk at her, but they will flutter and cede the lawn and return to the river.

Without preconception or planning or hidden meaning this final scene turns out to be the denouement to my morning thoughts.

Still on the Yellow Brick Road

As the year comes to a close, as the landscape, at least the political landscape, has shifted, is shifting in my country, as new books are written, as new promises are made, and not many (any?) broken, at least that I’m responsible for, it seems a good time to look back to the premise of this Substack that launched a year and a half ago and to peek ahead.

When I began this Substack at my publisher’s suggestion, two of my novels were being published—Burning Distance and The Far Side of the Desert. The novel Burning Distance came out in hardcover in 2023 and in paperback this past spring. The Far Side of the Desert was published this April and arrives in paperback April 2025. I have two new novels ready to find a home and readers. These novels were all written over the last decades, and the stories and struggles of the characters mirror times lived through and to an extent foreshadow the times ahead.

But no one can predict the future however prescient the imagination. The future is in part a product of what has come before, fueled by the imagination of what can be and held in each individual’s heart. The future begins with each and expands.

I resist the three or five or ten bits of advice and wisdom so prevalent on social media except to note that when love fuels the heart, it is a powerful guide and knows how to reach out to others. Hate negates. Hate is the absence of love and therefore can’t be obliterated with more hate. A wise woman, who shared wisdom from other wise men and women, once explained a simple guiding principle to me. Light overcomes darkness because darkness is only the absence of light. You can’t bring darkness into a room except by extinguishing the light. Why is light more powerful? Because it has a source—the sun, electricity—and darkness has no source. It is only the absence of light. For our lives and hearts, the source of light is Love.

So, in the spirit of moving forward by glancing backwards, I share below the essay that launched this Substack. I hope you’ll continue to enjoy and share the journey with me.

(launched August 2023)

A former journalist, I spend most of my writing time these days on fiction in a lifelong admiration for what literature can do. Good literature reveals characters and orders life into stories the reader can connect with and understand. We all live and remember our lives and the lives of others through the stories we tell and are told. History, politics, even religion are rendered through stories.

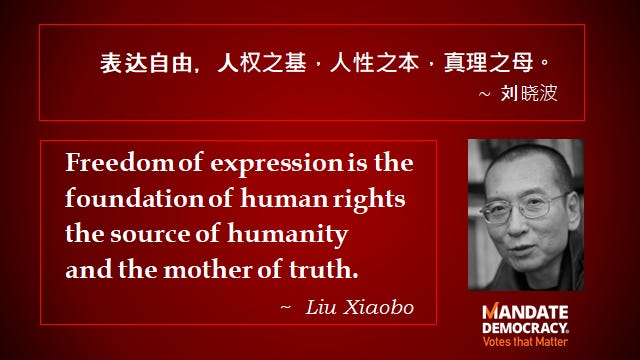

Because storytellers can be powerful members of society, the storytellers—usually the writers—are often the early persecuted, imprisoned and even killed in authoritarian societies as a result of the stories they tell. I’m a storyteller as are many of my friends and family who are journalists, fiction writers, dramatists and poets. We are fortunate to live in a country that, while stressed at the moment with the banning and censoring of books, still does not put its writers in prison or kill them, though the increasing pressure to ban books is alarming. Freedom of expression includes the freedom to have access to ideas. Imagination has always been the enemy of the tyrant because it can’t be controlled. I’ve spent time over the last many decades working on behalf of writers who don’t have the same protections and working with organizations that defend freedom of expression.

In my own novels—in particular my recently published novel Burning Distance and my next novel The Far Side of the Desert to be published March 2024—I’ve sought insight through narrative. Both books took a good deal of research into the factual context of the story and the inner journeys of characters. In naming this newsletter On The Yellow Brick Road, I pay tribute to L. Frank Baum’s iconic novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Interpretation is extensive on the many elements of this story and of the Yellow Brick Road in particular. According to commentary:

Collaboration, communication, innovation, positivity, nurturing, and fun are the six core values of Yellow Brick Road. The values emphasize team spirit, transparent two-way communication, support for new ideas, nurturing of bonds and relationships, a positive, solution-based mindset, and a fun learning environment.

Is that a mission statement? It sounds a bit like a gathering of strategic modelers at a conference. I’m not aiming for a didactic newsletter, but I think the values hold. I’d also like to have some fun and explore new thoughts and occasionally inspire.

Other commentary notes:

With the help of her newly-minted friends, Dorothy is able to melt the Wicked Witch of the West and save the citizens of Oz. No matter what the situation is, you should never allow that to get in the way of your morals.

With the help of new and old friends, I look forward to embarking on this path, alert to occasional wicked witches but mostly exploring ideas large and small. Thank you for coming along.

Join me on Substack

Words Matter…Ideas Matter…and Guide

I’m writing this blog on the eve of one of the U.S.’s most fraught—and many feel consequential—presidential elections, at least in my lifetime. By the time many read this, the results may be in, or contested. Recently one of my earlier blogs popped up in my email—I don’t know why—but I followed the link. Written in 2008, the blog addressed ideas that still resonate. I offer it here, slightly edited, with recognition that certain ideas endure and matter.

Words That Matter, March 4, 2008:

I’m writing this, my second blog, on the birthday of my oldest son and a day when much of the U.S. is watching presidential primary results. I find myself thinking about words, action and change—three concepts that have been debated relentlessly on the airwaves in this U.S. primary season. How do words link to actions that bring about change?

Let me start with my son who spends his days in abstract thought. He is a mathematician, a logician, whose thoughts and work are understood by only a very small number of people around the world. He’s taught more accessible math at universities, but his research time is spent thinking and then writing in words and symbols which only a few understand. When I asked him once how his ideas might be applied a hundred years from now, he smiled his patient smile and asked, “Mom, do I ask you how your literature might apply?”

All right, I get that. I understand the value of pure ideas, ideas for their own sake. I understand the need to think and to add to the universe of thought even if one doesn’t know the value the thoughts may have and even if they are shared with only a few. It is a way of ordering, discovering and revealing the harmony of the universe.

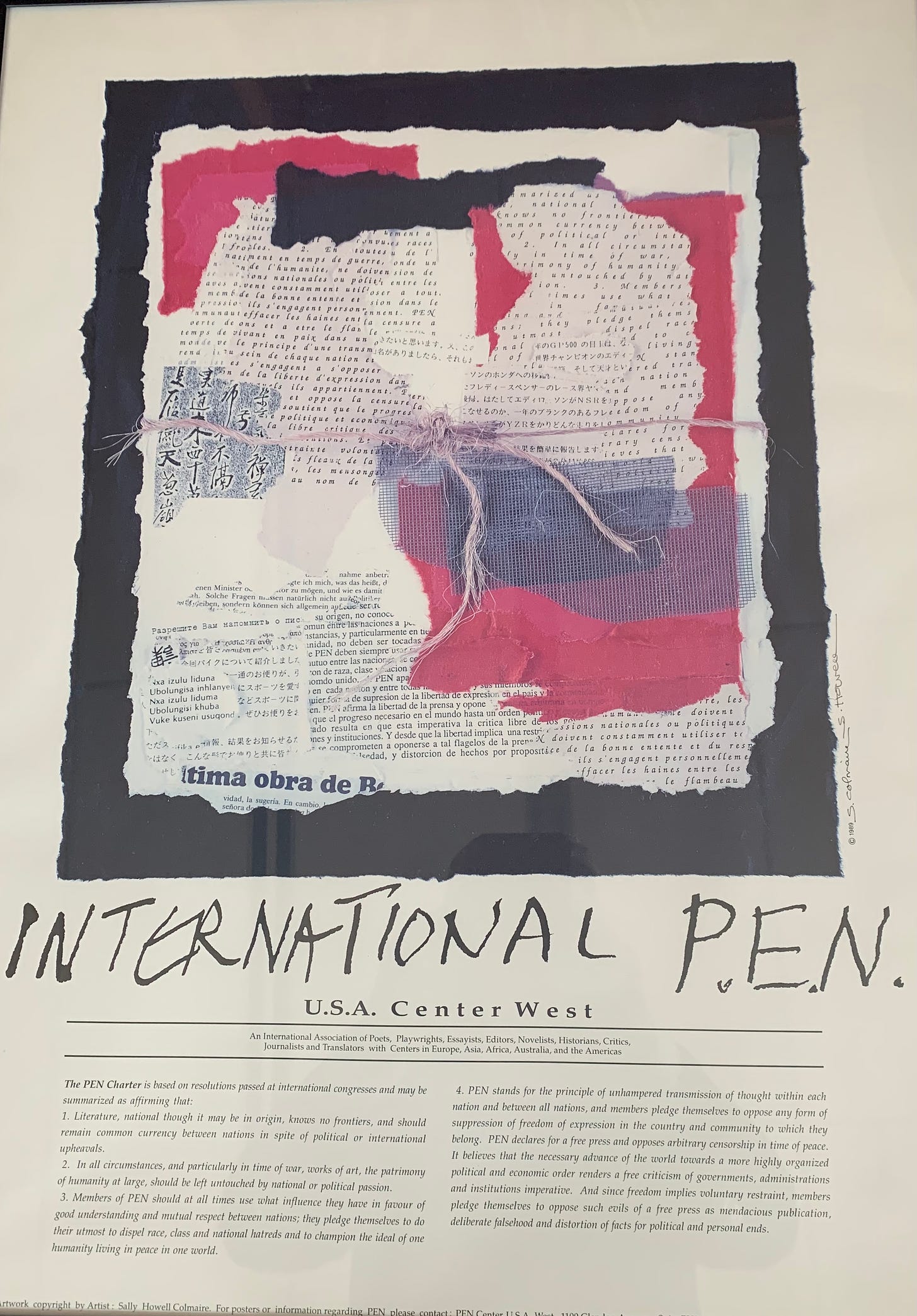

Now I want to jump—I wonder how I will do that—to take this narrative to the next idea—well, it’s my blog, no editor—so I can just jump any way I want. Sixty years ago, two documents came into being. One preceded the other by a few months. I have worked with and been inspired by the words and ideas in each. Both documents have brought about a lifting of the global consciousness. Because of these ideas, actions have been undertaken and at least some change has resulted. The first document is known by many in the worldwide community of writers and the second is known by the world at large. Both were developed in the aftermath of the atrocities of world wars. The first is the Charter of PEN International and the second is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

PEN’s Charter was 22 years in the making, and its articles were said to have been consulted by those working on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. PEN International’s first president John Galsworthy wrote the first three articles in 1926 after an argumentative gathering of writers from the East and West in the first international meeting held in Berlin after World War I. The articles he drafted were approved and served as “a touchstone of P.E.N. action.” Eventually they became part of the P.E.N. Charter, which affirms among other ideas that literature should “remain common currency between nations” and works of art “should be left untouched by national or political passion” and members of PEN should use their influence “in favor of good understanding and respect between nations.” The fourth article of the Charter which dealt with censorship was developed after the Second World War. The Charter in its entirety was approved at the Copenhagen Congress of P.E.N. in 1948 shortly before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights came into being.

Both documents were framed in an idealism that confronted the nihilism of the Second World War. The one document was developed by writers, who are suspected of idealism anyway; the other was drafted by experienced politicians, who labored to articulate ideals to which the world might strive.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights pledges nations to “promote universal respect and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms.” It was ratified by 48 members of the United Nations with no votes against and eight abstentions. The Declaration is the most translated document in the world today.

It is fair to question whether the words in these documents have led to actions that have brought about progressive change in the world. I suspect the conclusion would be that they have not. Yet it is worth pausing to ask where we would be without the articulation of these ideals set down decades ago.

It is just past the 75th anniversary of both documents. I want to pause to acknowledge and to celebrate the value of words and ideas, to share an optimism that in the long run of history, ennobling ideas and the words that frame them matter and can guide us even in the most fractious times as we set out to shape the future.

Join me on Substack

Finding Light in a Dark Time

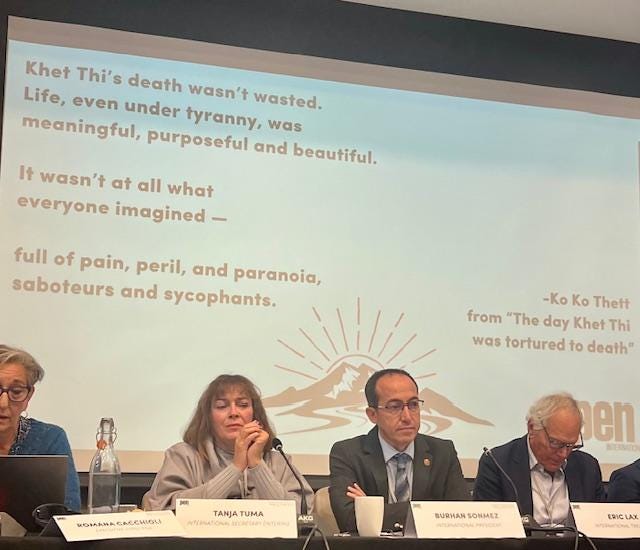

I’ve just returned from PEN International’s 90th World Congress in Oxford, England whose theme was “Writers in a World at War.” PEN originally planned to celebrate its Centenary in Oxford in 2021, but the global pandemic disrupted that gathering. This 90th Congress was co-hosted by English PEN, and while it was smaller than the planned Centenary, there were delegates from 80 PEN centers around the world and 20 more centers represented on Zoom. More than 200 writers participated.

Oxford, England at dusk

PEN International’s congresses have occurred annually except during World War II. The congress is a time when the conversation is live among writers from almost 100 nations in the more than 130 PEN centers. Literature is shared. Formal discussions focus on the challenges for writers at risk, in prison and threatened by authoritarian governments, the challenges of peace and displacement for those in conflict areas, the challenges of linguistic rights and translations and the ongoing challenges for women around the globe. These are addressed through PEN’s four standing committees—the Writers in Prison Committee, the Peace Committee, the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, and the Women Writers Committee. At this 90th Congress a new standing committee of PEN International was formed for the first time in 33 years. The committee will develop and give voice to younger writers and is based on the original premise of PEN’s founders for a Tomorrow Club.

PEN operates at both an individual and a global level. The work focuses on the individual writers in prison and at risk in countries such as China, Turkey, Vietnam, Myanmar, Cuba, Guatemala, Belarus, Russia, Egypt, Iran and others. Members write to their fellow writers in prison, to their governments, to the members’ own governments; they lobby on the writers’ behalf, celebrate their writing which the government has suppressed. At a global level PEN International speaks out at the United Nations Human Rights Commission and other forums seeking and urging pathways to free expression and to peace.

This later action via the Peace Committee is often more challenging and taxing to PEN’s mandate. PEN International President Burhan Sönmez noted, “War is the darkest word in every language. While peace is the longest word. Because it never comes to an end in any language.”

PEN International: (L to R) Executive Director Romana Cacchioli, International Secretary Tanja Tuma, PEN International President Burhan Sönmez, Treasurer Eric Lax

At the 90th Congress the lines of tension heightened as the issues of peace in Israel and Palestine and Gaza arose. The challenges in the Middle East have tested PEN and its Charter before. PEN’s Charter urges members to “use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people” and to “do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.” At the same time “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression….”

One of the panels at the Congress was devoted to PEN’s Charter, which novelist and poet Ben Okri described as “one of the great documents of the century, a foundational document.” Linked here, the PEN Charter was one of the documents studied in the development of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Drafted in the wake of World War I and World War II, the governing principle of PEN’s Charter is that “Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals. In all circumstances and particularly in time of war, works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large should be left untouched by national or political passion.”

How this mandate is fulfilled through resolutions and statements in a time of war as is occurring in the Middle East can challenge members. There are those who resist PEN stepping into geopolitical strategies and those who think PEN must not remain silent on these specific issues. Is peace just the cessation of hostilities or the resistance to those who would oppress? A resolution was finally voted on and passed, though not unanimously but with an understanding that the principles of PEN keep us together.

I quote here the words of former PEN International President, playwright Ronald Harwood, who I had the privilege of serving closely with during our shared terms at the Secretariat and with whom I agreed at the time and still in this more activist era. At a fraught Congress during the war in the Balkans in 1993, Ronny noted to the Congress:

“The world seems to be fragmenting; PEN must never fragment. We have to do what we can do for our fellow-writers and for literature as a united body; otherwise we perish. And our differences are our strength: our different languages, cultures and literatures are our strength. Nothing gives me more pride than to be part of this organization when I come to a congress and see the diversity of human beings here and know that we all have at least one thing in common. We write…We are not the United Nations…We cannot solve the world’s problems…Each time we go beyond our remit, which is literature and language and the freedom of expression of writers, we diminish our integrity and damage our credibility…We don’t represent governments; we represent ourselves and our centers…We are here to serve writers and writing and literature, and that is enough… And let us remember and take pleasure in this: that when the words International PEN are uttered, they become synonymous with the freedom from fear.”

Friends and colleagues at the PEN International 90th World Congress in Oxford, England, September 2024

Join me on Substack

A Moment Past As We Go Forward…

Affirming progress—“We won’t go back…” doesn’t prevent us from remembering and building on the past, acknowledging the ties that bind and helped us make the progress we’ve made and built the foundation from which we launch.

With this in mind, I looked back to a brief moment in time to see what I was thinking and writing in my September blog ten years ago in 2014. I can’t help but reflect on the illusion of time—how fast it moves (or appears to move) and how we circle within it as it wraps itself around us, then shoots us forward.

Boston on a Sunday Afternoon

By Joanne Leedom-Ackerman | September 8, 2014 |

The sun is shining. The swan boats are cruising on the pond in the Boston Commons. Joggers are jogging along the park. Children are running after ducks; parents are running after children. University students have returned en mass from summer so the hum of young people hums in Boston and its neighboring city of Cambridge, ever the student’s town. People from all backgrounds, speaking Spanish, Vietnamese, Arabic, French, Russian and languages I don’t recognize pass by as I sit on a park bench.

For a moment I don’t want to think about ISIS or terrorists’ attacks or the beheadings of writers, who are friends of people I know, writers and their families whom I can’t help but think about and want to honor, or to think about those who must decide what our country does next or those who will take the risk to do it.

All this is on my mind and on the minds of people in Washington, DC where I live. But for a moment I look out and take a breath and watch Boston on a Sunday afternoon before the world accelerates, a few days before we mark again the events of 9/11. I want to savor and remember this moment just for a moment. It is the point after all.

Join me on Substack

Barking at Thunder

After days of sun and blue skies and high, muggy temperatures, the clouds closed in, the sky darkened and the rain came. It was a relief. My morning routine is to get up early and sit outside before the sun starts to bake so that I can gather my thoughts for the day. During a recent storm which began in the night, I sat under the shelter of a side porch to watch the rain fall. My 15-pound, very smart, very fast Australian labradoodle Amie sat beside me.

As the sky darkened further and the rain fell harder, the thunder began, preceding and followed by lightning. At each roll of thunder, Amie leapt off the chair and ran into the yard barking fiercely at the thunder. She returned wet and satisfied when the sound abated and settled her soggy self back next to me. A few moments later, the thunder roared again louder and closer. Amie leapt to her feet and sprinted into the yard racing towards the river and the assaulting sound, barking at full volume.

“Don’t mess with me!” she seemed to be saying. “I’m not afraid! This is my home!” When the thunder retreated and the lightning blinked in the distance, Amie returned again soaked and settled beside me. After a third foray and defense against the thunder, I decided it was time to retreat inside. Despite her brave response and my enjoyment watching her and the storm, I take lightning seriously and decided the spectacle of a brilliant summer storm wasn’t worth the risk close-up. We watched the rest from the house with Amie at her post by the window and my morning thoughts unspooling on the sofa inside.

Barking at Thunder seems an apt description for our response to danger and the unexpected these days. My brave dog has no idea where the sound comes from, what it represents or how little damage thunder itself can do. Likely she doesn’t even see or register the lightning which is the danger. More to the point, she has no idea how irrelevant barking at the noise is, but her instinct is to protect and defend. The sound is fierce, even awe-inspiring so she responds in the way she knows.

The response to fear can often be as ineffectual as barking at thunder. I will resist taking this metaphor any further and leave it for readers to expand any wisdom or relevance it may have. I end with facts and advice on the literal example, not the metaphor, from the National Weather Service.

Happy summer…or winter depending on your hemisphere!

According to the National Weather Service:

Thunder is the sound caused by a nearby flash of lightning and can be heard for a distance of only about 10 miles from the lightning strike. The sound of thunder should serve as a warning to anyone outside that they are within striking distance of the storm and need to get to a safe place immediately!

Thunder is created when lightning passes through the air. The lightning discharge heats the air rapidly and causes it to expand. The temperature of the air in the lightning channel may reach as high as 50,000 degrees Fahrenheit, 5 times hotter than the surface of the sun. Immediately after the flash, the air cools and contracts quickly. This rapid expansion and contraction creates the sound wave that we hear as thunder.

Although a lightning discharge usually strikes just one spot on the ground, it travels many miles through the air. When you listen to thunder, you’ll first hear the thunder created by that portion of the lightning channel that is nearest you. As you continue to listen, you’ll hear the sound created from the portions of the channel farther and farther away. Typically, a sharp crack or click will indicate that the lightning channel passed nearby. If the thunder sounds more like a rumble, the lightning was at least several miles away. The loud boom that you sometimes hear is created by the main lightning channel as it reaches the ground.

Since you see lightning immediately and it takes the sound of thunder about 5 seconds to travel a mile, you can calculate the distance between you and the lightning. If you count the number of seconds between the flash of lightning and the sound of thunder, and then divide by 5, you’ll get the distance in miles to the lightning: 5 seconds = 1 mile, 15 seconds = 3 miles, 0 seconds = very close.

Keep in mind that you should be in a safe place while counting. Remember, if you can hear thunder, chances are that you’re within striking distance of the storm. You don’t want to get struck by the next flash of lightning.

Join me on Substack

Eyes On Pluto

With fraught political climates on the ground in many countries—at least 64 countries face elections this year with democracies in the balance—and with discourse often less than inspiring, I find myself looking up and into the clouds and the sky above for an uncluttered view. That instinct was further encouraged by a book I recently read and note in the Books to Check Out section of this Substack—David Ignatius’ Phantom Orbit. Even before reading this novel, I was recalling a major event in July nine years ago when the New Horizons spacecraft built by Johns Hopkins University’s Advanced Physics Lab gathered data and reported back from Pluto.

As a Hopkins trustee, I was privileged to watch the encounter along with others at the Advanced Physics Lab when the spacecraft reported from its Pluto orbit. “We’re in lock with telemetry with the spacecraft.” A cheer erupted! I re-publish here the story of the event which I still find stirring. The precision of calculations is astonishing, the vision expansive, and the cooperative effort and possibilities for the future inspiring.

Space is considerably more crowded nine years later and much has transpired. Space remains an open territory though one that we must hope doesn’t become clogged with earthbound conflicts and competitions.

EYES ON PLUTO…“WE DID IT!”

By Joanne Leedom-Ackerman | July 15, 2015

Headlines from earth yesterday heralded the Iranian Nuclear Deal, but some of us were looking skyward. On a small green campus tucked into suburban Maryland at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab scientists, engineers, media, friends, family, faculty and board of Johns Hopkins University awaited the report back from Pluto. The New Horizons spacecraft, built by Hopkins APL engineers and scientists, had arrived at the outer planet three billion miles away after a nine and a half year journey. That evening the spacecraft was reporting in after 22 hours of silence while it gathered extensive data as it passed within 7750 miles of Pluto.

The spacecraft, which had been built in a record four years at APL, had traveled at a rate of a million miles/day (between 31,000-46,000mph depending on its orbit). The evening before it had started downloading data and taking pictures in a rapid collection of scientific information. It couldn’t do that job and call home at the same time so its progenitors waited anxiously at Mission Control, aware that any number of unpredictable events like a pebble size bit of detritus colliding could disrupt and destroy the mission.

“Stand by for telemetry….” Mission Operations Manager (MOM) Alice Bowman alerted. At 8:52:37pm—right on time—New Horizons called home. “We’re in lock with telemetry with the spacecraft,” she affirmed as one by one the systems managers reported: “MOM, propulsion is nominal…MOM, thermal is nominal…MOM, power is nominal…” Nominal meant normal. MOM meant Alice. The conclusion: “We have a healthy spacecraft and we’re outbound for Pluto!” The room at Mission Control and in the auditorium nearby burst into cheers and tears and gave a standing ovation. It was a remarkable moment and extraordinary achievement.

This composite of enhanced color images of Pluto (lower right) and Charon (upper left), was taken by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft as it passed through the Pluto system on July 14, 2015.

The mission had proceeded like clockwork. It had been a team effort over a decade and a half, occupying 2500 people. The very best scientists and engineers built the space craft, designed its scientific mission (including the first student-designed project on a NASA mission), programmed its course. The trajectory included an important scientific data-gathering pass of Jupiter, where the spacecraft received a needed gravity assist which sent it hurling on its way into deep space.

New Horizons arrived at the closest approach to the planet just 72 seconds early. That precision over nine years and three billion miles was almost impossible to comprehend except to the scientists and engineers who understood that precision was essential to accomplish the task. Even a small margin of error projected over that amount of time and space could be disastrous.

The mission exemplified a remarkable achievement of teamwork and partnerships among NASA, universities, and the U.S. Department of Energy which supplied the plutonium power source. The nuclear power it provided will allow the spacecraft to operate until 2030. The total power draw for the Pluto encounter was only 202 watts (about three and a half light bulbs). Each transmission draws only 28 watts (enough to power two small night lights.) Reception of these transmissions relies on super giant receivers—the Deep Space Network. There are only three in the world large enough—one in Madrid, Spain, one in Pasadena, CA in the US and one outside Canberra, Australia. The placement of them means that data can be received at any time as the earth spins on its axis. Last night’s transmissions were broadcast from Pluto four and a half hours before they were received, traveling at the speed of light and sent via the giant antenna dish in Madrid.

Alan Stern, the head of the New Horizons Mission and NASA’s chief investigator, told the gathering: “We did it! One small step for New Horizons, one giant leap for mankind.”

The audience included students who had been born almost ten years before on the day of the New Horizons launch. An elementary school boy asked, “Does this make Pluto a planet?” Fran Bagenal, NASA team leader for plasma investigations on the Mission, answered, “Yes! Of course Pluto is a planet!”

The Pluto mission began as a barroom bet by Alan Stern to prove Pluto was not just a dwarf planet but a full planet. The exploration was affirmed as a top priority by the National Academy of Science. In the audience last night were the grown children of Claude Tombaugh, the astronomer who originally discovered Pluto. Eighty-five years earlier their father told his senior astronomer, “I think I have found your planet X.”

Fifty years before to the day—July 14—humans first explored Mars with NASA’s Mariner 4. John Casani, special assistant to the director at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and one of the early engineers in the space program noted, “People developing spacecraft today know what they are doing. We didn’t know what we were doing. Back then the shoulders we were standing on were too narrow and our shoes were too big. We had only the technology for guided missiles.”

The scientists and engineers had to figure out, among other concepts, 3-axis stabilization. “Innovation was the key to making things work,” Dr. Casani said. “There was no book on 3-axis stabilization. We were all only a couple of years out of graduate school. We weren’t experienced enough to know that what they were asking us to do couldn’t be done.”

“You couldn’t go to the library and ask for a book,” added Norm Haynes, who was the trajectory engineer for the Mariner 4 Mission and also spent his career at NASA’s JPL. “There were no textbooks on how to build a spacecraft.”

There were no computers on board the first spacecrafts either. In 1962 the computer had only a 65,000-word vocabulary as opposed to the multiple gigabytes of memory today. The first computer was aboard Mariner 4 which delivered 22 pictures of Mars, each taking ten hours to send back. It took 60 hours to go to the Moon, 6,000 hours to go to Mars and now the New Horizons spacecraft can endure a nine and a half year journey to Pluto and still arrive in tact. The per mile cost of New Horizon was 25 cents/mile; the per mile cost of Columbus was $3000/mile and the per mile cost of Magellan was $5000/mile. On Mariner 4 in 1965 the spacecraft transmitted information at 8 1/3 bits / second; New Horizon transmits at 1000 bits/second and it is 60 times further away.

The scientists and engineers said the key to success was the willingness to imagine, to innovate and to be willing to fail. Considerable failures preceded this achievement.

Why is the exploration of Pluto important? It opens up our view of what is possible, of the universe and perhaps even of ourselves, suggesting larger horizons physical and metaphysical. It demonstrates the possibilities of human potential—of imagination and ingenuity empowered by cooperation, teamwork and a large goal. From a scientific point of view, from the point of view of NASA which has to secure the funding, it provides knowledge about the universe where we live and the universe beyond.

The data that will be gathered on the New Horizons’ close approach to Pluto is about 100 times more than can transmit before the spacecraft flies away. It will take 16 months to send all the scientific information home.

“We explore because we are human, but we want to know,” said noted physicist Stephen Hawking in a call-in message to the gathering.

If the next stage is funded, the New Horizons spacecraft will go off to explore the outer reaches of the Kuiper Belt, letting us know what lies beyond Pluto in the further reaches of space.

The spacecraft was built to last. Its power will endure until 2030, then it will not be sufficient to keep the instruments warm enough to operate, and the craft will drift into deep space. By 2030, the equipment on the spacecraft will be 40 years old and the innovations that will have developed by then we can now barely imagine.

Credits: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

Join me on Substack

Calm Before and During the Storm

Poised on the threshold of summer, of university protests and disrupted graduations, of US political conventions in July and August, of threatening weather with tornados and hurricanes churning on both US coasts and in the middle of the country, I pause in a patch of early morning sun to savor and seal a moment of calm.

Though I won’t be at the political conventions—may even be out of the country for one of them—and will hopefully miss the worst of summer weather, storms appear on the horizon, and it does no harm to prepare by identifying and fixing one’s North Star.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Before the arguments begin or untruths unfurl, or provocations proliferate among the citizenry or even in one’s own family during the US election season, I pause in gratitude that we are allowed to disagree and even protest nonviolently. I am grateful when journalists I know and those I read and listen to work to uncover facts and report in an unbiased fashion. These, however, are not my North Star. I rely instead on a more transcendent light, lodged deeper in a universe that moves towards harmony. I see evidence of this harmony in people caring for each other in the smallest details, in strangers who regularly hoisted my heavy suitcase filled with books and papers into the overhead for me as I traveled on a book tour, in the Uber driver originally from Uzbekistan who stopped en route in NYC to buy me a bottle of water. Small kindnesses we offer each other are the fabric of our citizenry and the evidence that we can be and continue to evolve into a more perfect union.

In the most intractable conflicts between nations, it is the citizens who inevitably must find peace with each other, and perhaps it is with the citizens that the seeds of peace can begin to grow even when politicians are deadlocked. I recall stories from the Balkans War in a memoir Worlds Apart by Ambassador Swanee Hunt. I quote here from the review I wrote in The Christian Science Monitor a decade ago, along with a link to the full article.

The city is surrounded. Shelling rains down on the population. Sniper fire, bombs, mortars erupt from all directions. There are no safe havens for civilians; dozens are killed each day. The international community meets, protests, debates what should be done. Powerful players like Russia obstruct action. Sanctions are tightened, but it is citizens who suffer most. Outside nations are willing to offer humanitarian aid, but are conflicted about arming the opposition. The UN organizes peacekeeping forces, but the mandate and rules of engagement are unclear. The siege and the deaths continue … for years.

This description could be from today’s headlines in Syria, but instead it is the siege of Sarajevo in Bosnia 20 years ago. The paralysis of the international community to intervene and prevent the killings of citizens is still haunting.

In Worlds Apart, former Austrian Ambassador Swanee Hunt chronicles her years (1993-1997) on the inside and the outside of the corridors of war in Bosnia. As the US Ambassador located in Vienna, she sat at embassy dinners, met with European and US government officials, engaged in countless discussions of what should be done. She also used her position, both geographic and political, to visit with the citizens of Bosnia dozens of times in the country and to bring citizens outside the country to meet with each other….

I hope you’ll read the full review linked above and also the book.

And so I will continue to pause in the mornings and savor the light and the promise and endeavor to add my own small and large kindnesses along the way.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Join me on Substack