Posts Tagged ‘Boris Yeltsin’

PEN Journey 8: Thresholds of Change…Passing the Torch

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

In fall, 1991 I went to Moscow just months after the August coup attempt in which hardline Communists sought to take control from President Mikhail Gorbachev. I hopped onto the visa of my husband who was traveling to Russia as a Visiting Scholar at the International Institute of Strategic Studies in London. I went as a writer, interested in meeting other writers. I contacted fellow PEN member and Russian translator Michael Scammell, who had previously chaired International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). Michael gave me a list of writers to contact in Moscow.

Statues toppled of Lenin and Stalin and others in park after failed coup attempt in Moscow, 1991.

My husband and I stayed in what I was told was one of the government hotels where guests were hosted but also watched. We were watched too, I’m fairly certain, though there was little for anyone to see with me. I was cautious as I made contact with the writers lest my reaching out compromise them. Only a few years before, PEN’s case list had included many dissident Soviet writers in prison. Michael and later WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack and PEN’s WiPC committees around the world had advocated for the release of dissident Soviet writers, many of whom were imprisoned in the gulags. PEN had also covertly sent aid to them and their families through the channels of the PEN Emergency Fund.

I no longer remember if I called or faxed the writers in advance. (Fall, 1991 was before an active internet.) I likely made contact when I arrived. The writers welcomed me. We met in simple apartments with old holiday cards on the mantles as decorations, a paper mobile hanging from the light fixture over one dining room table I recall, strips of newspaper stacked by the toilets in lieu of tissue. The economy was spare for these writers. They hoped for change and for freedoms to come, but they were cautious. In these meetings and in other random encounters, people were curious about the United States. On the street, vendors not only sold Russian nesting dolls with the rushed visages of Boris Yeltsin, who had defied the tanks of the coup, and of Gorbachev but also stacking dolls of U.S. presidents, including one set that had George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. I was asked by numbers of people, including the writers, if I could get them copies of the U.S. Constitution and the Federalist papers. The Berlin Wall had fallen and times were changing, but no one knew how that change would settle out in the Soviet Union.

Stall of street vendor selling Russian Matryoshika dolls, including stacking dolls of Boris Yeltsin and Mikhail Gorbachev and also U.S. Presidents.

I remember one meeting in Moscow with members of a women’s theater cooperative—actresses, director, costume designer, and playwright. Before the member who spoke English arrived, we were left to communicate with each other by hand gestures and a few common words. Finally, the sturdy, broad-chested Russian writer who spoke English entered. I asked her what she did during the coup attempt. She stood, spread out her arms and declared triumphantly, “I stopped the tanks with my breasts!” This image has stayed with me, along with her words and the determined words of her fellow thespians and writers in that apartment, women demanding as their due freedoms they hadn’t yet experienced.

Joanne and members of Russian women’s theater cooperative in Moscow apartment, 1991.

Not only in the USSR but elsewhere, old dictatorships were crumbling, in Africa and Latin America. PEN was a refuge writers often looked to before democracy and political liberalization took hold in their countries. In September 1991 at the Vienna Congress, a month after the coup attempt, the Soviet Russian Center applied and received approval to change its name to Russian PEN. The debate within PEN was when to recognize a center. It was necessary to have enough qualified writers committed to the freedoms embedded in the PEN Charter and to have an environment in which the writers could feasibly operate, at least to some extent.

As the USSR broke apart, writers gathered and petitioned for PEN centers, sometimes before the regions claimed full independence. A PEN Center of the Soviet Asian Republics, including the literatures of the five separate regions of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tadzhikistan had been recognized at the Paris gathering in April 1991, but by PEN’s September 1993 Congress in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, writers from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan all proposed separate centers of PEN. Russian PEN supported the disbanding of the Soviet Central Asian Center because it had not functioned, because the Soviet Union no longer existed, and because the President of the center had made public statements racially slandering others, and he refused to withdraw these. It is rare for PEN to challenge a member and withdraw membership, but the use of PEN to advocate racially intolerant and provocative positions is a rationale; PEN did so as well with certain members in the Balkans during the war there.

The Kazakhstan Center was accepted as a PEN Center at the Congress in 1993; the vote on Kyrgyzstan’s proposal was delayed until more information about the writers could be gathered, and it was agreed the situation in Turkmenistan, still governed by a dictatorship, remained too problematic for a PEN center to exist.

PEN often mirrored the global landscape. In the early 1990’s PEN added centers in Albania, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Bosnia, and an ex-Yugoslav Center for writers in exile from the former Yugoslavia. Also new centers formed in the Congo, Mozambique, Malawi, Kenya, Guadalajara, Palestine as well as a Chinese Writers Abroad Center, an Iranian Writers in Exile Center, and an African Writers Abroad Center. The abroad and exile centers included members living outside the regions. At the Barcelona Congress in 1992 the acceptance of a Palestinian PEN Center was unanimous, including by the Israeli PEN and represented a hope that writers in the region would engage with each other. Also a Welsh Center and an Esperanto Center were added in the early 1990s.

PEN was growing quickly. It doubled in size in ten years, from 50 centers to more than 100 centers in 1992. Its finances, however, did not grow at the same rate, and the governing structure was essentially the same—an elected President, International Secretary and Treasurer who comprised the executive of International PEN. Staff also had hardly grown. Elizabeth Paterson, the Administrative Secretary had to manage the increasing workload with the addition of Jane Spender as her assistant. The Writers in Prison Committee, which operated with a separate budget, in a separate room, consisted of only two researchers—Sara Whyatt ,coordinator, and Mandy Garner and later a few interns.

During Michael Scammell’s years as Chair of WiPC and later during Thomas von Vegesack’s term, the Writers in Prison Committee focused its work on behalf of imprisoned and threatened writers, and on occasion tension arose between the Secretariat’s goal of promoting literature and comity among writers and the WiPC’s goal of protecting writers in oppressive regimes. The ultimate organizational decisions fell to the Secretariat between Congresses and in consultation with the Assembly of Delegates which met twice a year at Congress. Because of budgetary restraints and the growing size and expense of the Congresses, PEN reduced its Congresses to only once a year, beginning in 1994.

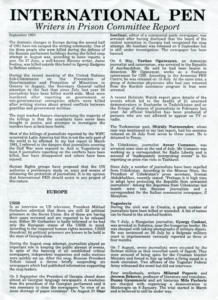

PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee Report, September 1991 presented to the November 1991 PEN Congress in Vienna. PEN’s complete Case List for this period included 143 pages of cases of writers and journalists around the world reported kidnapped, “disappeared,” executed, having died in custody, imprisoned, banned, under house or town arrest, deported or awaiting trial.

Controversy around the narrow base of decision-making came to a confrontation over the April 1993 Congress in Dubrovnik, Croatia. The Balkan War was raging. At the Rio Congress in December 1992 the American delegate questioned the wisdom of holding the Congress in a war zone not only for reasons of safety but also for the appearance and possible “political misuse” of PEN in one corridor of the riven community and the restrictions on talking freely with the press. Others felt holding the Congress, most of which would be on a ship that would sail from Venice to Dubrovnik, would have a symbolic message of peace and also commemorate PEN’s Dubrovnik Congress 60 years earlier in 1933 when PEN exlcuded official writers of Nazi Germany from the organization. The host center assured that all centers from the region would attend. When delegates asked that the Dubrovnik Congress either be cancelled or postponed, they were told the decision had been made two years before, and there was no need for the Assembly to take a vote. Later as the war escalated, a mail vote was taken and the majority who responded voted for postponement, but the Croatian center, which had put in considerable work, wanted to hold the Congress, and so the plans went ahead.

On April 12, a week before the PEN gathering, the Army of the Republic of Srpska launched an attack on the town of Srebrenica in Bosnia, 200 miles from Dubrovnik. Many PEN Centers chose not to send delegates, including American and German PEN. The Writers in Prison Committee in the person of Thomas also chose not to attend nor did many of the WiPC members. Because there was not a quorum, the gathering was declared not an official congress, but a meeting.

I did not attend either the Dubrovnik meeting nor the earlier Rio Congress. Before the November 1992 Congress in Rio, Thomas and International Secretary Alexander Blokh without consulting with each other asked if I would take over the Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee when Thomas finished his term in September 1993. The fact that these two individuals both came to me made me consider carefully, but I was among the younger generation of PEN members who was urging more democratic procedures for PEN. I didn’t think the Chair should be an appointive office but should have the input of the PEN members, but in 1992, PEN had no such systems in place. Alex told me that he would canvas people at the Rio Congress to see if they agreed and get back to me. I don’t know what process was used nor how widely he asked, but he and Thomas returned in agreement and urged me to accept. I agreed, though I said that when my term was up, I wanted to assure we had set in place a more democratic system for nominations and election of the WIPC Chair. And so we did and have ever since.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 9: The Fraught Roads of Literature