Posts Tagged ‘İsmail Beşikçi’

PEN Journey 19: Prison, Police and Courts in Turkey: Initiative For Freedom of Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

We sat on the ferry drinking strong Turkish coffee then handing over the emptied cups to a woman who read fortunes from the pattern of the leftover coffee grounds. As we huddled in the wind off the Sea of Marmara en route to the prison in Bursa, we speculated who among the passengers was following us. We were assured we were being followed.

Program for Initiative for Freedom of Expression Gathering, March 1997

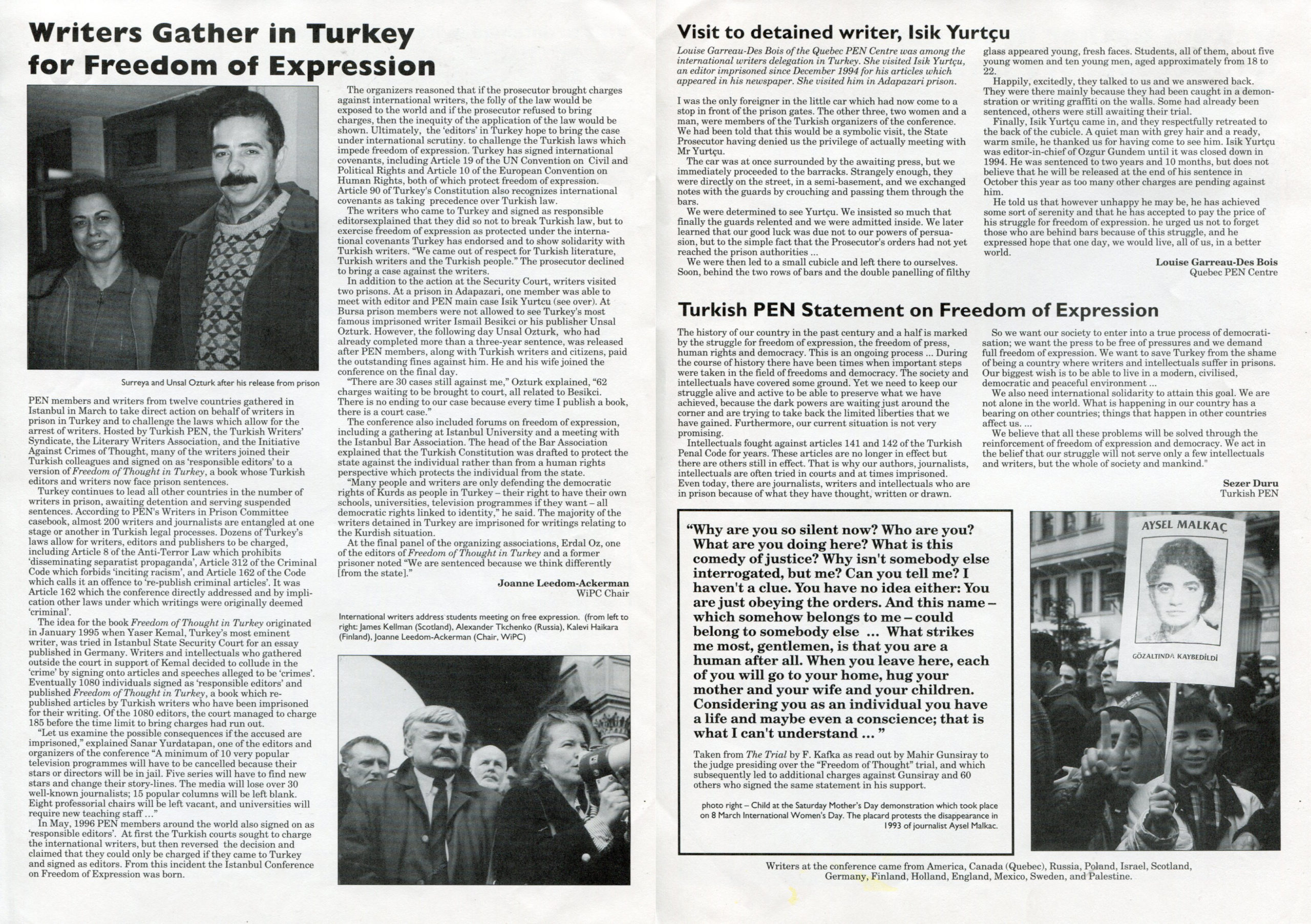

I came to Turkey in March 1997 as the returning Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WIPC) (PEN Journey 18). I was heading a delegation of 20 PEN members from 12 countries. We’d arrived to support Turkish PEN, the Turkish Writers’ Syndicate, the Literary Writers Association and the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in the first Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression. We had signed on as “publishers” to an abridged version of the book Freedom of Expression. The original book included essays by those who were in prison or facing charges for their writing, particularly former president of Turkish PEN, the prominent novelist Yaşar Kemal. He was tried for an article he’d published in the German magazine Der Spiegel. (PEN Journey 17). Headlined “Campaign of lies,” the article called out the government for its human rights abuses, particularly its treatment of the Kurds.

Arthur Miller letter to Yaşar Kemal, March 1997

Bearing a letter from Arthur Miller, who knew Kemal and had himself come to Turkey with Harold Pinter in solidarity a dozen years before, I was among the 141 “foreign publishers” of the booklet Mini Freedom of Expression. This book contained a paragraph from each article published in the larger book. We joined the 1080 Turkish “editors” of the larger volume who included writers, theater actors, politicians, painters, cinema actors and directors, cartoonists, musicians, trade unionists, academics, lawyers, architects and others. The Turkish Penal Code made it a crime to re-publish an article that had been defined as a “crime” so that the publisher as well as the writer was charged.

The “publishers” had presented themselves before the State Security Court and faced charges of “seditious criminal activity.” After questioning the first 99 people, the prosecutor demanded the accused be tried under Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law and Article 312 on “disseminating separatist propaganda.” After six months only 185 of these individuals had been questioned and brought to trial. If these individuals were given the usual 20-month jail sentence, that would mean ten popular television programs would have to be canceled because their stars or directors would be in prison; five series would have to find new stars and change their story lines. The media would lose over 30 well-known journalists; 15 popular columns would be left blank. Eight professorial chairs would be left vacant, and universities would require new teaching staff. Theater stages and film sets would require many other artists, directors, musicians, etc., and 20 new books about prison life would be added to literature if every author wrote.

Turkey already had over 200 writers either in prison or entangled in legal processes, more than any other country. This protest initiative was unique and creative. The challenge to the court was to bring charges against so many. The State Prosecutor had dropped charges against the foreign participants on the grounds that he wasn’t able to bring us to Istanbul for questioning though the Turkish citizens who had prepared and distributed the booklet could be tried. The organizer of the initiative Şanar Yurdatapan suggested we come to Istanbul and challenge the prosecutor. Though PEN members were willing to come to support their Turkish colleagues, no one wanted to end up in a Turkish prison.

“No one will go to prison,” Şanar assured. The prosecutor had to act within six months, and even in the unlikely event charges were brought, we’d go home before a trial, and there was no extradition from the US, UK and many other countries because no such “offense” existed under their laws. Unlike organizations such as Greenpeace, PEN was not a direct action organization. PEN dealt in words, protest letters, diplomacy, meetings, on occasion candlelight vigils outside embassies and stories in the media. But Şanar, who was a song writer, civic activist, not a PEN member, instinctively understood the dynamics of nonviolent direct action and understood how to get attention and make the point that the Turkish laws were unjust and unfairly administered.

On our first day, which was Women’s Day, we joined the Saturday Mothers’ rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members. The gathering had been held every Saturday for a year and a half at Galatasaray Square, ten minutes from our small hotel in Taksim. The crowd of mothers and children held pictures and signs of their loved ones, mostly Kurds, who had been taken away, assumedly by the government and likely killed. On the edges of the crowd police in riot gear gathered but didn’t interfere. Meeting at Galatasaray Square is now banned for Saturday Mothers by the Ministry of Interior since August 25, 2018. They still keep the rally at Human Rights Association branch in one of the back streets.

Saturday Mother’s Rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members.

From there a number of us went to a women’s rally where hundreds of Kurdish women in traditional dress marched with banners shouting, “We are mothers; we are for peace! Mafia is in Parliament; students are in prison.” Along the route men cheered and dozens of police lined the road frisking and checking bags. This was the last weekend of a 40-day protest all over Turkey. At 9pm every night people around the country turned out their lights or blinked their lights and shouted out their windows and in the street, “Go Away!” in protest over the government. The idea was that people would have one minute of darkness to get years of light. At dinner that Saturday evening we watched as the streets filled with shouting and the lights in restaurant blinked on and off.

Women’s Day march of Kurdish women with police positioned along the route.

The trip to Istanbul was my first of what would turn out to be dozens of visits to Turkey over the years for PEN, for other organizations, and for family. In 1997 the times were tense; soldiers with their weapons and machine guns were stationed at the airport; armed police were on the streets; we were followed; the phones at the hotel were likely tapped. It was difficult to imagine then that it would get much better in the following decade as it did and then much worse in recent years. I’m not sure today we could hold such a gathering with confidence.

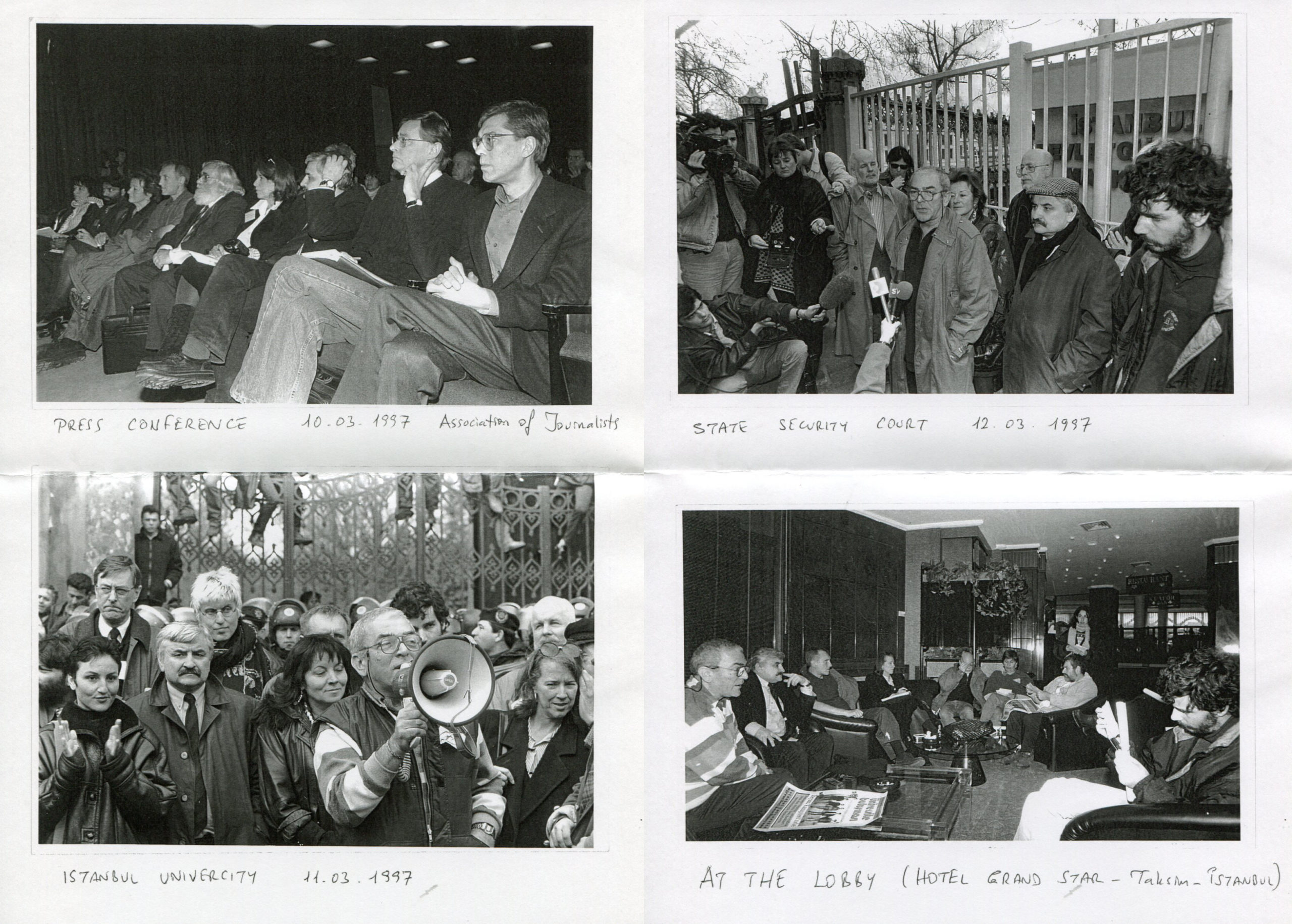

Throughout our visit we were covered by the press, including two visits to the State Security Court. In 1997 the legal way to meet publicly was to hold a press conference so we spent our days in press conferences, including one at the Journalists Association. Because I was Chair of the WiPC, I was often the one explaining why we were there. I emphasized that we had come out of respect for Turkish literature and writers. We had not come to break Turkish laws; we did not consider editing a book a crime. We were there to uphold the international covenants that Turkey had signed, approved and became a party to: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 19), Article 19 of the UN Convention on Civil and Political Rights and Article 90 in the European Convention on Human Rights. We noted that Article 90 in Turkey’s own Constitution declared that no law should supersede these international covenants.

Our PEN delegation included representatives from Canada (Quebec), Finland, Germany, Holland, Israel, Mexico, Palestine, Russia, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States and Turkey. The delegates included James Kelman, Booker Prize winner from Scotland and Turkish writers including Yaşar Kemal, Orhan Pamuk and others.

PEN members from 12 countries join Turkish colleagues for dinner at the first Gathering of the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in Istanbul, March 1997

On Monday we started the day at the State Security Court where Şanar petitioned the prosecutor for an appointment to question one delegate who had to leave early. Because the prosecutor didn’t want to bring charges against “international editors”, an act that would bring international attention, the “Turkish editors” could use this failure as further evidence of the unfair nature and application of the law when they took the case to the World Court. We approached the State Security Court again on Wednesday, when the prosecutor actually locked the gates and wouldn’t see any representative of our group. In the end nine of us—from USA, England, Scotland, Finland, Holland, Sweden, Canada (Quebec), Mexico and Russia—signed a form which said, “I accepted to be one of the collective publishers of this book willingly and I am aware of the legal responsibility. I have nothing else to say.” These forms were then sent registered mail to the prosecutor.

Two small groups visited prisons and the prisoners of conscience, including Dr. İsmail Beşikçi and his publisher Ünsal Öztürk in Bursa and journalist Işık Yurtçu in Adapazarı prison. Louise Gareau-Des Bois from Quebec PEN went to the Adapazari prison and was able to visit with Işık Yurtçu.

Kalevi Haikara from Finland and I went with Şanar on the ferry to the prison in Bursa where we met Ünsal Öztürk’s wife Süreyya. We waited and waited and talked together in the bleak courtyard with grey concrete walls rising around us topped with barbed wire, with guard towers looming over us. We went to the pink concrete building of Bursa Prison with a shield on the door “Ministry of Justice Bursa Special Prison” and waited there too. But we were not allowed to see İsmail Beşikçi, the noted Turkish sociologist and philosopher who wrote about the Kurds history and living conditions. He was one of the few non-Kurdish writers in Turkey speaking out about the treatment of the Kurds. At the time he was also one of the longest serving prisoners. He’d been sentenced to over 100 years though he was released from jail two years after our visit. Of his 36 books, 32 were banned in Turkey.

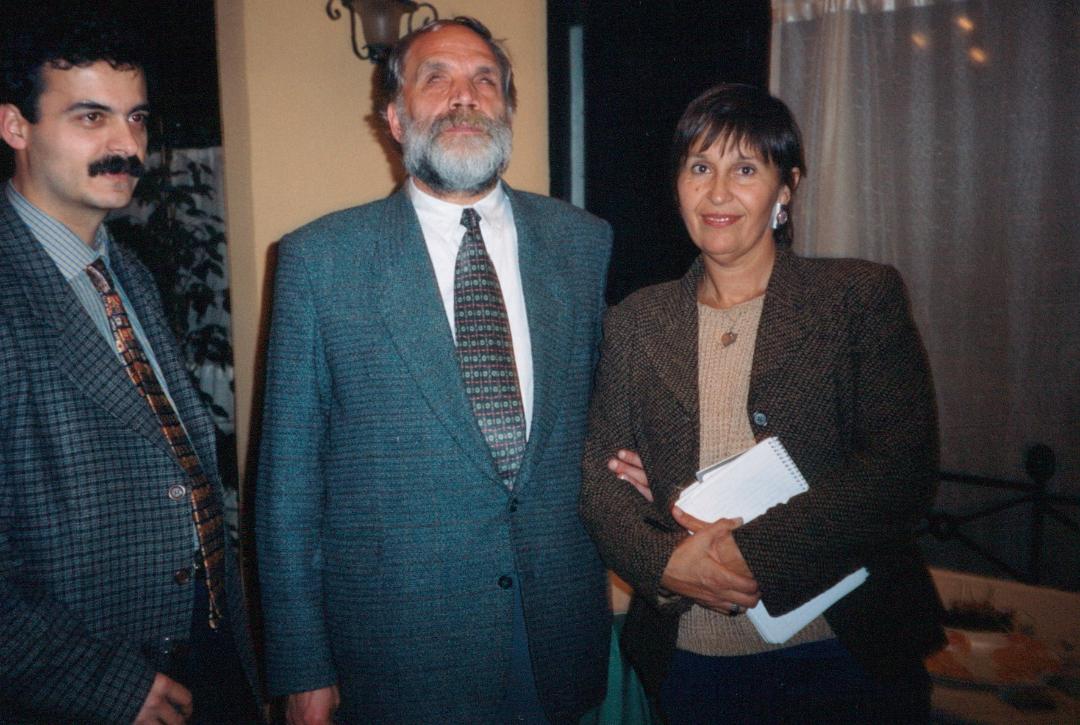

Kalevi Haikara from Finish PEN and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, WiPC Chair and member American PEN outside prison in Bursa, along with Süreyya, wife of prisoner Ünsal Öztürk (middle picture) and in conversation at Bursa Prison (far right picture.)

We were also not allowed to see Ünsal Öztürk, Beşikçi’s publisher, who had completed more than a three-year sentence. We met with the press which had gathered. We paid the outstanding fine against Öztürk with funds raised from Turkish writers, artists and many of the visiting PEN members. Öztürk was released the following day though there remained 30 outstanding cases against him, 62 charges waiting to be brought to court, all relating to Beşikçi. Every time he published a book, a charge was brought, but he kept publishing. Öztürk and his wife joined the conference.

The following day we attended the Justice House hearing of the “Kafka Trial.” When one editor of the Freedom of Expression book—actor Mahir Günşiray—faced the judges, he’d read a paragraph from Kafka’s The Trial. The paragraph offended the judges, and they brought a civil suit against him. Sixty-five other writers and artists signed on and said they also endorsed the reading of Kafka and should thus be guilty too. We all piled into the small room where the defendant Mahir Günşiray and his lawyer and the judge met. The hearing was the second or third for him, but with the room full of observers, the judge again postponed the proceedings.

At hearing of “Kafka Trial” in the Justice House

Many of us went next to Istanbul University to participate in a Forum on Freedom of Expression. However when we arrived, hundreds of students were protesting in the plaza, surrounded by riot police with shields. The situation was tense. In Ankara students had recently been arrested after they’d unfurled a banner in Parliament challenging the 300% tuition increase at state universities. The student protesters there were tried with the demand of 18-year prison sentences. The students at Istanbul University asked if we would speak at the rally. None of us were prepared for this potentially explosive scene. The writers who’d come to speak on freedom of expression asked me to talk for the group, all except Sascha from Russian PEN who also wanted to speak. Sascha, Şanar and I addressed the crowd. I emphasized that we were there to uphold the right for free expression, not to take a side with any particular party of government or to take sides on how education was financed in Turkey, but to insist that individuals should have the right to discuss, debate and write about these issues without facing prison terms. We urged that the protest stay nonviolent. We were then ushered out through the police corridor.

Rally at Istanbul University (Includes Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN), James Kelman (Scottish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Kalevi Haikara (Finish PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (WiPC Chair/American PEN), Hanan Awwad (Palestinian PEN), Turkish writer Vedat Türkali, and Şanar Yurdatapan (with bullhorn).

In the evening the Istanbul Bar Association hosted us. The head of the Bar noted that the Turkish Constitution protects the state against the individual rather than the other way around as in the US. Everyone agreed there was free expression in many quarters of Turkey, but that the danger arose when one addressed Kurdish issues and Kurdish separatism and referred to the PKK.

Attending the meeting was the former PEN main case Eşber Yağmurdereli, a blind poet/dramatist, who’d served 14 years in prison. Released August 1991, he’d spoken in September 1991 at a meeting on behalf of Kurdish prisoners and had new charges brought against him. After five years he was still awaiting the resolution of that case. His passport had been taken from him. He could be sent back to prison for more than 20 years. He said he was unable to write, and if he wrote, he had to hide the writing and not publish. He earned his living now as a lawyer.

Meeting with Istanbul Bar Association. Eşber Yağmurdereli (middle) and Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN) on right.

I also met the young brother of Bülent Balta, an investigation case. Balta, a chemistry honors graduate, a Turk, not a Kurd, had agreed to edit Özgür Gündem, the Kurdish newspaper, because of his sympathies for the difficulty of the Kurds. He had no particular experience as an editor, and after only 11 days was arrested and was serving a four-year prison sentence.

That evening the protest at Istanbul University was all over the news, including pictures of me with a bull horn speaking, but my words had been translated into Turkish so I had no clear idea what it was reported I was saying.

Early the next morning I slipped out of our hotel and walked to a large international hotel nearby where I called home. I asked my husband to confirm my return flight the following day. He asked what the flight was, but I told him to check with the travel agent and confirm. Over the phone I didn’t want to give flight details. I told him what was happening, including the widespread coverage of the protest with my participation, and he told me a colleague in Washington said that the American Embassy knew I was there and warned me not to leave the hotel. I had to leave the hotel, I explained. I was leading the delegation and events were planned, including a farewell dinner on the Bosphorus.

At the final panel/press conference, I noted that I had two sons, and as I observed the young people here, especially the young police officers and the young students, I felt sorrow that these youth were set across battle lines from each other. There was so much talent and promise we had seen. For the first time in the three days of speeches and press conferences, emotion stirred in my voice and I paused for a moment. One of the headlines the following day read something to the effect: “She Cries for Turkey!”

Panel at Initiative for Freedom of Expression Conference, Istanbul March, 1997

The following morning I was to be driven to the airport, but the driver didn’t show up, and I was left to find my own transportation in a taxi. The atmosphere around the conference had slowly made each of us cautious, even slightly paranoid. As I climbed into the taxi, driven by a stranger, I remembered the fortune teller on the ferry a few days before. Proceed with caution…was that her warning? You will make friends…was that the prediction? The road ahead is fortuitous but also fraught? In fact, I no longer remembered what her fortunes were, and I didn’t believe in fortunes or scattered coffee grounds, but I left Istanbul with a strong belief in the people and a commitment to the country and to the writers and publishers and lawyers and journalists and to the young people I had met and to the promise they represented.

In years following I returned to Turkey on numerous missions for PEN and for meetings with Human Rights Watch, with the International Crisis Group, on a trip with UNHCR looking at the Syrian refugee crisis, and several trips with my oldest son who wrestled in the World Championships and European Championships in Ankara and in the World Championships again in Istanbul and also lectured in mathematics at Koc University and other universities and with my youngest son who lived in Istanbul for two years with his two young children and wrote as a journalist on the Turkish/Syrian border and has set two of his four published novels in Turkey.

PEN International Writers in Prison Committee Centre to Centre newsletter special Turkey section April 1997

Next Installment: PEN Journey 20: Edinburgh—PEN on the Move, Changes Ahead