Posts Tagged ‘Turkey’

Time of Repose and Preparing

It is a blustery August day on this fulcrum between summer and fall when the breeze stirs with a hint of the season ending. A pandemic stretching 18 months continues to unhinge life from what is considered normal, if there ever was normal. Life is far from normal in Afghanistan or Haiti right now. Normal is a relative term, residing perhaps in the hope for a measure of peace, for supply of basic needs and for the kindness of others.

This month I am again posting a retrospective of August blogs with a view of the last thirteen years’ history, a history which I read with nostalgia, recognizing those times are gone. It is difficult to imagine getting on a plane now to Tanzania or Kyrgyzstan or Macedonia with the same confidence of work to be done and the ability to meet those on the other end also engaging. The world may return as it was, though I’m not sure life ever returns as it was. But I hope it will transition to a world still connected and willing to connect and build with each other.

The geography of these posts range from Tanzania to Turkey to Qatar to France to Slovenia to Kyrgyzstan to Ghana to Macedonia and several in the United States. Readers can click on the date and title to read the full post. I am halfway through a year of posting these retrospectives and note that August is the first month where I’ve posted every year. I’m struck by the sultry beauty of this month between seasons, a time of repose and preparing.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

August 31, 2008: From the Edge of the Indian Ocean

I’m sitting looking out at the Indian Ocean from the eastern edge of Africa in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. It is Labor Day, at least in the U.S., though in the U.S. it is actually still Sunday night; but here it is morning with billowing white clouds, blue sky, palm trees, sun shining through—the end of winter in the Southern Hemisphere.

It took 17 hours of flying and a few hours of waiting in Amsterdam—roughly 20 hours to get here. When I arrived in the hotel room last night and the bellman turned on the TV, the BBC in a pulsating picture and sound was reporting on the approach of Hurricane Gustav to New Orleans and the interruption of the Republican National Convention. Was this important news in Tanzania? It was, in any case, the BBC news, and I was interested but couldn’t help but note how far one can go and still have America follow.

Outside the window in the hotel this morning, men are cutting the grass by swinging machetes across the lawn. From a distance it looks as if they are practicing their golf swings, but in the morning sun they are tending to the grass without lawn mowers or power tools.

In the following days here and in Uganda I’ll have the opportunity to visit schools and projects where educators and writers are responding to the shortage of books for children, particularly books with stories relevant to the children and books in local languages. This morning I’m aware of the stories we carry with us, the narrative in our heads wherever we go, the power of this narrative in shaping our lives and the importance of listening to the stories of others and opening up the narrative.

“Once upon a time in a place where the sun usually shines and the winds blow through the palm trees, there is a little girl who lives on the edge of the Indian Ocean, and every morning when she wakes up, she…”

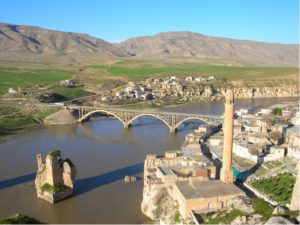

August 31, 2009: Turkey Can Avert a Tragedy on the Tigris

It can develop energy and progress into the future without washing away the town of Hasankeyf, its jewel of the past.

From The Christian Science Monitor

Washington – In the southeastern corner of Turkey near its borders with Iraq and Syria, environmentalists, human rights organizations, and archaeologists recently won a battle in the effort to avert a cultural tragedy.

Swiss, German, and Austrian firms pulled out of their contract with the Turkish government to build a dam that would flood and destroy a historical ancient city, harm ecosystems downstream, and displace thousands.

To permanently protect this area though, it should be designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Ilisu Dam, a cornerstone in a project to develop Turkey’s electrical and water capacities, is the largest and the most controversial of the 22 dams and 19 power plants scheduled in the $32 billion Southeast Anatolia Project.

At the heart of the controversy is the town of Hasankeyf, carved into the limestone cliffs above the Tigris River. Hasankeyf is reputed to be one of the oldest continuous settlements on earth, at least 10,000 years old, with relics found this summer that may date it to 15,000 years old.

In the Kurdish region of southeastern Anatolia, Hasankeyf has hosted at least nine civilizations, including the Assyrians, the Romans, the Byzantine Empire, the Mongols, and the Ottomans. On a central trading route in ancient Mesopotamia, Hasankeyf boasts more than 4,000 caves; 300 medieval monuments; 83 archaeological sites with ruins, including Hasankeyf Castle, built by the Byzantines in AD 363; and historic tombs and mosques. Its cultural and archaeological value is priceless.

Today the hillsides are dotted with artisans’ stalls, children on donkeys, and caves with restaurants inside.

If the Ilisu hydroelectric dam is constructed as planned 50 miles downstream, much of Hasankeyf – historic caves, ruins, and all – will be buried under 400 feet of water….[cont]

August 30, 2010: On the River: the End of Summer

Boats skimmed along the Potomac River this last weekend of August—power boats, yellow and red kayaks, boxy green canoes, sleek white sculls. I settled into the latter late Sunday afternoon, dropping oars into the warm water. Many in Washington are still out of town—on vacations or home visiting constituencies—but in their place are tourists exploring the nation’s capitol. The heart of the city beats on in festive cadence.

Baking in the summer sun, I eased leisurely down the river—past the Kennedy Center, the Watergate apartments, past the Georgetown waterfront where outside cafes were filled with people eating and bicyclists walking their bikes, past the new park along the river, then under Key Bridge, where a moment of shade brought relief. On the bridge above bikers and runners and cars crossed the river to and from Virginia. My scull sliced the surface of the water past the spires of Georgetown University, which peeked through the trees on the shore like a medieval fortress. I aimed out to the Three Sisters Islands, rowing with one oar to turn the scull then traversed the river, crossing the wakes of larger power boats so I could return on the opposite side, rowing past the nature preserve of Roosevelt Island towards the public boat house.

By the time I neared the home shore, sweat was dripping down my brow into my eyes, blurring my vision. The sun was slowly sinking in the sky, but relinquishing none of its heat. The boat house was already closing, and kayaks and canoes were pulled up on the dock; mine was one of the last sculls to return.

Summer is near its end. On Labor Day next weekend American flags will flutter beside the Potomac, and the political season with midterm elections will shift into high gear. But before the business of campaigns and politicians fill the air, summer may yet linger for just a bit longer like a temporary denouement before the pace of life accelerates. I take a moment here to savor the summer, which has been spent almost entirely in Washington—one of the hottest summers on record—a summer of writing, reading good books and welcoming into life a new grandchild. It has been a summer of quiet pleasures and great moments.

August 27, 2011: Before the Earthquake and Hurricane: Summer Music in the Afternoon

The air is surprisingly cool for late August. I’m sitting on an upstairs porch looking out over the tops of trees in their full dress of summer greens—maples, magnolias, dogwoods with white blossoms. The branches and leaves sway and rustle in the breeze. Somewhere a wind chime answers the moving air with a light ting and ringing like a message in the near distance, signaling the change of seasons. Overhead, shifting faces of white clouds drift through a blue sky, sliced by faint streaks from the trail of a jet that has long since passed by.

In this moment before evening, before the shift in seasons and the rush of autumn, I can almost hear the earth singing. Harmonizing with the wind chimes are thousands of crickets exploding with sound then quieting and birds sweeping through the sky calling to each other. The rustle of the trees, the call of the birds, the chirping of the crickets, the swoosh of the breeze are like nature’s symphony–an unexpected summer moment on this quiet August afternoon.

I sit high enough off the ground to see the sunlight golden on the tree tops and also to see the trees dark green, almost black, where the sun has left and the afternoon shadows have spread. I look down on the roses in a neighbor’s garden and look out on the brick chimneys of other neighbors’ houses.

I’m aware of the different voices of nature around me, each communicating its renditions of life, none of them taking notice of who will run for President of the United States, or who will emerge in power in Libya and Syria, or how the markets will close.

A flock of birds suddenly swoops past talking loudly to each other. What do they see and say and know?

[This post was written late afternoon Aug. 22. At 1:50pm on Aug. 23 Washington, DC shook as a result of an unusual 5.9 earthquake. As I edit this, we await the arrival of Hurricane Irene, characterized as a once-in-a-lifetime hurricane. The locusts, we hope, will pass us by.]

August 30, 2012: Diplomacy on a Summer Evening

It is a sultry evening at the end of summer in Washington, a backyard party on a patio with picnic tables on the deck, red Christmas lights strung across the porch and the night filled with animated conversation among ten Pakistani journalists and their American friends and hosts.

The journalists are soon returning to Lahore, Karachi, Balochistan, Islamabad and other cities and provinces in Pakistan. For the last month they have been working in newsrooms across America. Most are here for the first time, witnessing and learning about American culture and sharing their own culture and experience. They have worked from Tallahassee to Tucson to Los Angeles, from Washington, DC and Baltimore to Providence and Pittsburg; one journalist reported from Minnesota. They have covered American elections, crime, state politics, the judiciary, education and economics.

The Pakistani journalists have also met with the communities, including addressing hundreds of members of the Rotary Club in Tallahassee and having a one on one discussion with a Catholic bishop about abortion.

In their month they all agreed their misperceptions of America were changed.

–I thought Americans would be rude, said one and others agreed that that was their preconception. Instead they were friendly and helpful everywhere.

–They were very friendly, said another, but in Minnesota, they had little knowledge of Pakistan and held some myths.

–When people think of Pakistan here, they think only of terrorism. That was the general misperception.

–I saw how hard Americans worked. I always thought Pakistani journalists were energetic, but an American newsroom—that is energetic!

–I lived with the executive editor, and we were in the newsroom by 7am.

–I was impressed by the huge facilities in American newsrooms. The journalists are very professional. But I come away very proud of my fellow Pakistani journalists who work in much worse conditions.

–I was surprised that 50% of the staff was women. I even had a woman driving me.

The International Center for Journalists will bring 160 Pakistani journalists to work and live in the United States, and has sponsored American journalists into Pakistani newsrooms.

As we shared chicken tandori and lamb sausages and curries and rice in the fading summer light, the guests all agreed that this type of professional exchange opened and advanced relations between people in a way that politicians can’t or don’t.

–I covered the Governor and State legislature, said one reporter. The Governor was lobbying for his bills, especially to get his bill passed on gambling. It was just like Pakistan!

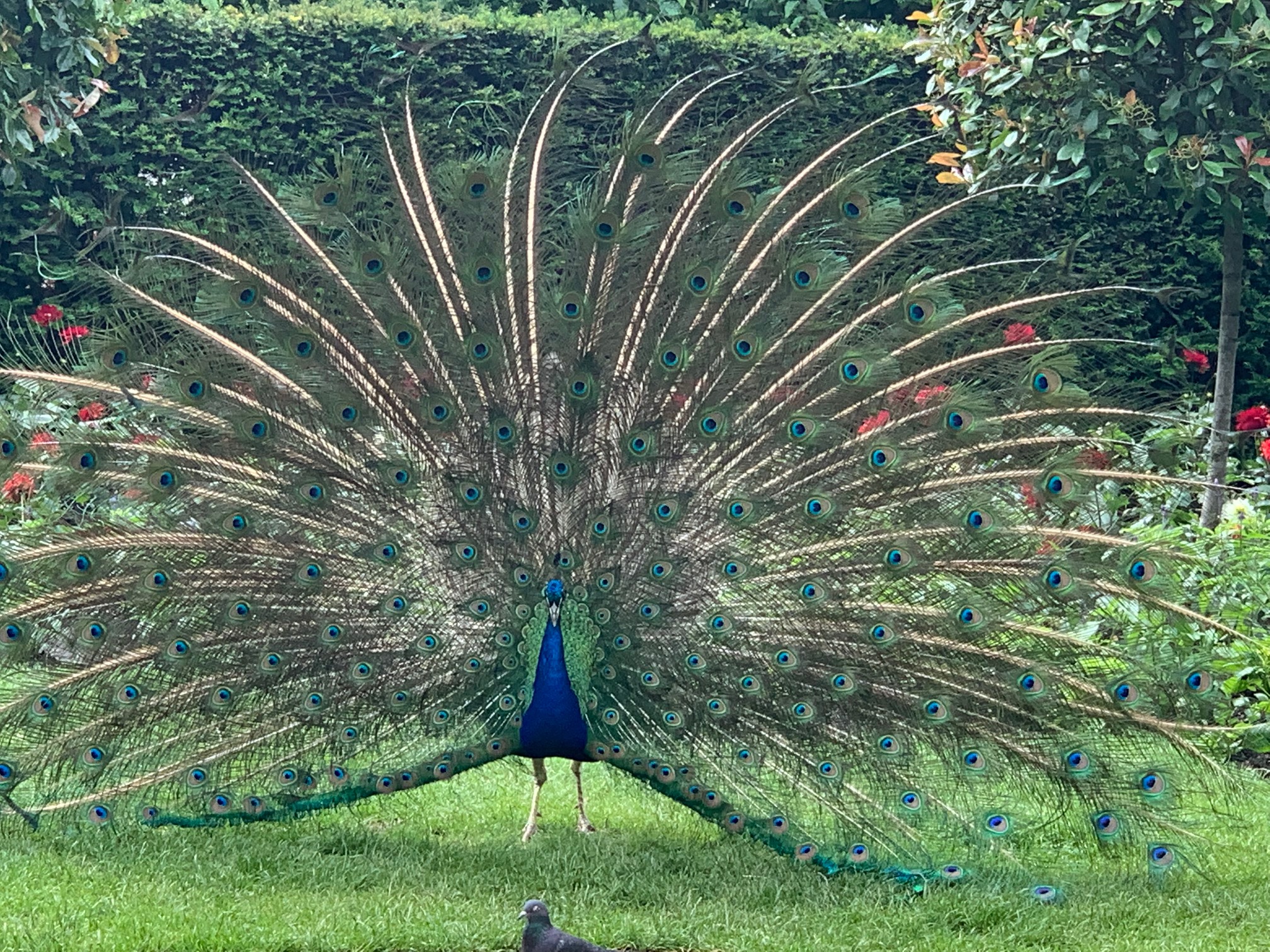

August 21, 2013: Peacocks and Politics

I’ve spent much of the summer on the Eastern shore of Maryland on a river, writing and listening to the quiet lapping of the water against the stones of the river bank, except when jet skis whish by and when the peacocks next door caw and caw at the neighbor’s farm. The peacocks call to each other all day long, broken by a rooster’s cock-a-doodle-do…actually the rooster is yodeling now, though I don’t know what he’s heralding in the middle of the afternoon.

The peacocks wander over from time to time, running across our yard like stealthy children hiding from their parents. I don’t know what prompts their visits. They usually leave a mess, but their brilliant feathers swishing by always surprise and astonish me.

Today as I was moving to a table outside to write this blog, I discovered one of the females nesting, hidden in a bush outside the house and, I believe, hatching a brood of eggs. I don’t know when she arrived, but she lay there motionless as though she had gone into a deep sleep, moving not at all as she protected her eggs. I’m not sure how long gestation is for peacocks, but soon we will be host to baby peacocks! Since the birds wander from farm to farm, no one claims ownership, certainly not me, but suddenly I feel a responsibility, for exactly what, I can’t say, at least a responsibility to give the mother the peace and quiet she has sought by escaping here, away from the other peacocks and roosters. Occasionally we have a dog visit on the weekend so my first responsibility is to make sure the dog doesn’t find the peacock….[cont]

August 2, 2014: Poets, Pardons and Ramadan

(This piece appears on GlobalPost.)

Eid—the end of Ramadan—has come and gone. Traditional pardons have been handed out. In Qatar, poet Mohammed al Ajami (Al-Dheeb), was not among them. He continues to live in a prison in the desert, serving a 15-year sentence for two poems, one praising the Arab Spring and the other critical of the Emir. He (and his poems) “encouraged an attempt to overthrow the regime,” according to the charges.

The over 70 pardons granted in Qatar are reported to have gone to Asian workers charged with theft, rape, drug abuse, bribery, prostitution, etc. These workers will now likely be deported. If Mohammed al Ajami were released, he would also likely leave the country to reunite with his family and then perhaps accept a brief fellowship offered as a poet at a major university.

Throughout the Muslim world Ramadan is a time when dispensations are handed out— as many as 1000 prisoners reportedly released in Saudi Arabia, 800 plus in Dubai, over 350 in Egypt— to individuals charged with violent and nonviolent crimes. But the amnesties were not given to writers, not to poet al Ajami, not to Egyptian journalists or Iranian bloggers. The offense of words and ideas are perhaps judged more dangerous.

Writers in prison in the Middle East who did not get pardons include: Bahrain (3writers), Egypt (5 writers), Iran (35 writers), Qatar (1 writer), Saudi Arabia (2 writers), Syria (11 writers), Tunisia (1 writer), United Arab Emirates (2 writers). *

August 27, 2015: “What to Read Now: War Narratives”

From the September/October 2015 issue of World Literature Today

While the US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been going on for fourteen years, much of American literature from these conflicts is only now emerging. I appreciate the veterans who’ve woven the simultaneously “worst and best days of their lives” into literature. They have turned to all forms to find their truth—poetry, short stories, memoir and the novel. (Disclosure: I’m the mother of a Marine who served in both conflicts and is now one of the novelists listed here.)

I have framed these suggested readings with a history from the Great War a hundred years ago and with a diary of one of the long-serving detainees in Guantánamo. Truth in literature is determined in part by point of view. In these books, the reader can take a journey from many perspectives.

Margaret MacMillan

The War That Ended Peace

Random House

In this nonfiction book, Margaret MacMillan narrates history through the lives of those responsible for World War I. The characters and cousins could populate a fiction collection with their dramas, imaginations and absurdities. MacMillan offers an inside view, revealing the people and stories behind the politics and events that led to a war many feel—and felt at the time—shouldn’t have happened.

Brian Turner

My Life as a Foreign Country: A Memoir

W.W. Norton

The author writes of his deployment as an Army sergeant, beginning in the US learning to identify body parts, watching combat on television, and then arriving in Iraq and facing real combat in the first Stryker brigade. “We rode on a war elephant made of steel,” he writes of the nineteen-ton tank. A poet (Here, Bullet), Turner narrates his experiences and his return home in a poet’s language, which spins the harshest circumstances—the soggy, trodden straw—into gold and art.

Phil Klay

Redeployment

Penguin Press

A veteran of the US Marine Corps assembles a dozen short stories and first person narrators—soldiers on the front lines, in the rear, at desks, with their family, friends, wives and girlfriends back home. The narrators’ voices are witty, unflinching, nostalgic, and the stories make the reader laugh, cry and wonder how a generation honed on this conflict will return to life as it was.

Elliot Ackerman

Green on Blue

Scribner

This novel narrates the war in Afghanistan from the point of view of an Afghan orphan who gets caught up on the American side of the conflict in order to keep his brother alive. He quickly learns that the war has too many sides and so many points of view that truth shimmers only in the eyes of the beholder.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Larry Siems, ed.)

Guantánamo Diary

Little Brown

Guantánamo Diary tells the story of the “war on terror” from the point of view of one who has been detained, tortured, and continues to proclaim his innocence. With a literary and humane voice, Slahi, edited beautifully by Siems and redacted by a censor, renders the horror and humanity in this war that will not end.

August 11, 2016: Sounds of Summer

(This is not a poem)

August on the Eastern shore

Quiet on the river

Birds chirruping in the trees

Crickets—or are they cicadas—clicking in the afternoon, clicking that will build to a crescendo in the evening

CaCaCa of peacocks next door

Water trickling, flowing slowly out to the bay

A power boat whishing by, heading to the open water

A leaf blower, a lawn mower in the distance, jarring the quiet

Leaves rustling in the breeze

Breeze skimming the trees, rustling, rushing louder now, emboldened

More birds chirping, the beginning of a larger conversation

At the very top of a tree at the river’s edge a black bird keeps watch, looking first out to sea then to land, then trips lightly along the branches, lets out a caw and flies away.

I sit here, listening to all these sounds of late summer.

I sit here, listening to all these sounds of late summer.

Soon the children will come home from camp, run outside, filled with their day—karate lessons, swimming, new friends—but for now in the quiet, I am “happy in my circle of oblivion,” to borrow a phrase from Garcia Márquez, whom I’m reading on this rare, undisturbed afternoon.

The news—the sturm and drang of presidential politics, the daily offenses—are outside this space on the river. For a brief moment the troubles of the world seem held at bay. Even the trials and triumphs of the Olympics must await the evening news.

I watch three billowing white clouds drift by ever so slowly in the blue sky.

As the breeze picks up, the trees rustle, continuing a conversation, stirring first one tree then another, passing along the wind’s gossip down the river bank.

If this light wind holds, it will be good kite-flying weather in the evening. We can have another picnic by the river with grandfather sitting in the Adirondack chair and everyone else on the grass—hot dogs, hamburgers, corn, applesauce, kite in the air, children running, laughing.

The parade of clouds drifts by overhead now like characters in the children’s play they plan for the grownups. “One, two, three…look at me!” The black dog passes all dressed up to play a part in the drama as he looks for scraps from dinner. The shapes of the clouds pass and just blue sky shines overhead. We will end the evening with S’mores at the fire pit as the moon rises over the river.

There are only three more weeks of summer—more books to read, stories to write, laps to swim, thoughts to think before the demands of schedules and meetings and deadlines crowd in.

For this moment I am grateful for the silence, the breeze, the birds, the river, the shining sky, the billowing clouds and the promise of this afternoon that I will carry with me.

August 14, 2017: The Beginning of Violence

In the wake of events in Charlottesville, Virginia last weekend, I wanted to share my short story “The Beginning of Violence” set at the first sit-in in Nashville, TN in 1960, published in No Marble Angels and republished in Short Stories of the Civil Rights Movement: An Anthology (ed. Margaret Earley Whitt, University of Georgia Press, 2006.). The anthology includes 23 short stories by black and white writers—stories of the heart, not just politics—an historic journey worth embarkation.

THE BEGINNING OF VIOLENCE

by Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Nashville, 1960

The wind shot through you that day like fate or some might say like the will of God. No matter what you did, it got you. It weaseled under the buttons of your coat, pulled off your scarf. You couldn’t fight against it though you could stay indoors, but once you came out, you had to face the wind and find your way.

It was the day before Valentine’s, and snow was falling in thick wet flakes, had been since early morning and threatened to keep on all afternoon. As I said, it was not a day to be outside, but I was. I was downtown on the arcade doing last minute shopping for a sorority party that night. We’d been decorating all morning, but we’d run out of crepe paper and balloons; and Janie, the food chairman, was afraid she’d run out of paper plates and cups so I said I’d go downtown and pick up everything.

I went to Woolworth’s. At the Grand Ole Opry counter I bought a red plastic guitar set inside a big red plastic heart for the centerpiece on the officer’s table. I was an officer. I was treasurer of the Kappa Alpha Thetas at Vanderbilt University.

I didn’t feel like turning right around and going back into the cold so I stopped at the lunch counter for coffee and a grilled cheese sandwich. I was sitting there eating and reading “When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d” for English class when a blast of air swept across my back. When I turned to see who was holding the door open, I saw dozens of Negroes coming into the store.

They moved straight down the aisles then disappeared among the cheap jewelry and face powders and school supplies.

I turned back around and finished my sandwich and Whitman’s poem. I was about to pay and leave when three Negroes sat down at the counter, one of them next to me. They all held brown paper bags with purchases they’d made. The girl beside me smiled, showing a curve of white teeth and asking more than most people thought she had a right to ask. I looked over my shoulder and saw thirty or forty more Negroes lining up to sit at the counter.

It took me a minute to understand what was happening. I’d grown up in Arkansas and Tennessee, and in nineteen years I’d never eaten beside a Negro. I’d never sat next to one on a bus or gone to the same bathroom. Things were changing in the South, but these were facts I’d lived with. Once in high school in Little Rock I’d signed a petition favoring integration, and that had almost gotten me thrown out of cheerleading. Some people thought anyone for the Negro was a Communist. I wasn’t a Communist; I just thought the Negro should have a chance. And yet even feeling that way, I wasn’t prepared to have the order of things put to question right where I was sitting.

The girl kept smiling. She had a soft mouth and big, dark eyes. Her hair was straightened, and she wore it like mine, in a pageboy with bangs. She was taller than me, and under her coat she looked strong. When she saw my poetry book on the counter, she reached into her pocket and took out a copy of the same book. I couldn’t help but feel she’d just drawn her gun…[cont]

August 3, 2018: Peace: Fabric with a Million Threads

Earlier this summer I had the opportunity to moderate a panel of high school teachers at the United States Institute of Peace called “A Year in the Life of a Peace Teacher.”

United States Institute of Peace in Washington, DC

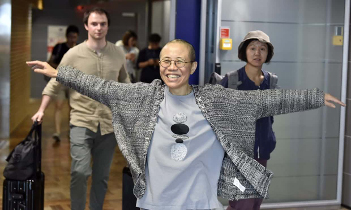

On that morning of July 10 two positive news events broke: the final young soccer players and their coach, who had been trapped for almost two weeks, made it out of the caves in Thailand. And Liu Xia, wife of Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese Nobel Peace Laureate who died last year in custody, landed in Europe, released after a decade of virtual house arrest in China.

For me these events connected to the panel on the teaching of peace-building.

Was peace possible? Could peace be “built”? The answer we concluded that morning with cautious optimism was: Yes.

The miraculous rescue of the soccer team resulted because highly skilled citizens from nations around the world, including the U.S., Australia, Denmark, Britain, China and most importantly Thailand came together and exerted their best efforts with a common goal everyone agreed on.

Freedom for Liu Xia resulted in large part because citizens and politicians around the world spoke up and advocated on her behalf though a similar effort had not won the release of her husband.

That morning, listening to the teachers and their work with students reinforced a view that peace was not just building bridges between two opposing pylons or signing treaties, but was the weaving of hundreds, thousands, millions of threads, of each citizen taking responsibility within his/her own community.

Each year the U.S. Institute of Peace, founded in 1984 as a nonpartisan Institute to promote peace and resolution of conflicts around the world, also focuses on the U.S. and selects four high school teachers for year-long training which they take into their classrooms. They work on problem-solving and peace-building in their communities and also study global peace opportunities.

This year’s teachers from Missouri, Montana, Florida and Oklahoma shared ways they and their students ignited discussion in their classrooms and in their communities and then took initiatives relating to issues of race, immigration, etc. They emphasized the understanding that peace didn’t mean avoiding conflict but rather finding ways to engage nonviolently and then to find ways to resolve conflicts by listening, determining the interests of the other, showing empathy.

Specific stories of the teachers and their journeys with their students can be heard on this link.

To conclude the panel it was appropriate to quote Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo. In his career and in his final statement to the court before he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for his writing and work towards democracy, he told the judge: “I have no enemies and no hatred.” In his life Liu explained that to build a society without hate, one had to begin with one’s self. After he died in custody last year, many questioned whether he would have claimed this had he known his end, but those who knew him well said he would have because he believed the responsibility for a peaceful and fair society began with oneself.

Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people… It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, it can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.

It was poignant and fitting that day to see Liu Xiaobo’s wife Liu Xia’s smile as she landed in Helsinki.

August 2019: [Beginning in May 2019 I started writing a retrospective of work with PEN International for its Centenary so posts were more frequent in 2019-2020. In August 2019 there is one post in the PEN Journeys and in August 2020 there are three.]

August 1, 2019: PEN Journey 7: PEN in Times of War and Women on the Move

Iraq invaded Kuwait August 2, 1990. When I picked up my 10-year-old son from camp in the U.S. that summer and told him what had happened, his first response was: What about Talal and Alec? These were two of his good friends at the American School in London—one was son of the Kuwaiti Ambassador; the other was from Iraq. He quickly understood the consequences. Fortunately, both of his friends had been out of their countries at the time, though I don’t recall Alec returning to the American School that fall. When the bombs dropped on Baghdad in January, the American School went into lockdown. The older students were issued identity cards. The security force around the school multiplied. When Talal came over to play that winter, he was accompanied by two imposing bodyguards who stayed outside.

Though the fighting in Iraq concluded by the end of February, security in London continued. By the end of March, the war in the Balkans had begun. Both wars brought to a close the honeymoon many felt after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

For PEN, the outbreak of war in Iraq and in the Balkans led to the cancellation of the planned Delphi Congress and to the convening of conferences in Europe and a two-day gathering of PEN’s Assembly of Delegates and international committees in Paris in April 1991. Delegates from 39 PEN centers came together to conduct the business of PEN at the Société des Gens de Lettres de France which occupied the 18th-century neoclassical Hôtel de Massa on rue de Faubourg-Saint-Jacques in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. There were no literary sessions or social gatherings, or the usual simultaneous translation of proceedings. The business was conducted primarily in English with intermittent French, the two official languages of PEN. (Spanish was added a few years later as PEN’s third official language.)

The Gulf War, the ethnic conflict in the Balkans, the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square trials and the ongoing fatwa against Salman Rushdie predominated discussions in Paris and later in November at the 56th PEN Congress in Vienna. The Gulf War had resulted in increased numbers of writers imprisoned and killed in the Middle East and an increase in censorship. Resolutions condemning the detention and imprisonment of writers in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Israel and Turkey passed the Paris Assembly. Little information was available from Iraq. Another resolution in Paris sponsored by the two American centers expressed concern to the U.S. government and all U.N. member states over the restrictions placed on journalists during the war and urged a review of the ground rules for journalists in conflicts….[cont]

August 5, 2020: PEN Journey 37: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part Two

At PEN’s 71st World Congress in June 2005 over 275 writers from 88 PEN Centers gathered from around the world in the idyllic setting of Bled, Slovenia where history had been made 40 years before. In 1965, PEN had held its Congress in Bled, the first in Eastern Europe since the Second World War. Russian writers visited PEN for the first time. At that 33rd World Congress, American playwright Arthur Miller, who’d recently passed away in 2005, had been elected the first and only American President of International PEN.

Lake Bled in Bled, Slovenia, site of PEN International’s 71st World Congress, 2005

In 2005 the global dynamics had changed. PEN now had active centers in most of the countries in the former Communist Eastern bloc, including in Russia. The European Union (EU) was in its ascendancy; 2005 marked Slovenia’s accession into the EU. Globalization was bringing benefits but also threats to the cultures of smaller countries.

Reception 71st PEN Congress in Bled, 2005. L to R: Frank Asare Donkoh (Ghana PEN), Jane Spender (Program Director PEN International), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Secretary), Alfred Msadala (Malawi PEN), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (PEN Executive Director), Dan Khayana (Uganda PEN), Bao Viet Nguyen-Hoang (Suisse Romand PEN) [Photo credit for many photos: Tran Vu]

“We live in an age when many preconceived ideas, nurtured for centuries and ostensibly immutable, are no longer valid,” noted Slovene PEN President Tone Peršak. “The linguistic and cultural image of the world is in flux and civilization as a whole, under the influence of globalization, is taking on a new character. These events are also echoed in discussions within PEN centers…They guided us in our selection of the main topic for discussion at the Congress, namely the issue of linguistic and consequently cultural diversity of the world. The topic is proposed as a question: does linguistic diversity stimulate or hinder cultural development? Is it a curse or a blessing that made possible the emergence and encounter of various world views, different emotional responses to the human destiny, and finally also brought about the formulation of different schools of thought and philosophical doctrines?

“We regard the question of linguistic and cultural diversity also as a human rights issue. Attempts to unify and subject all aspects of life to uniform standards and norms is viewed as a very questionable encroachment on these rights. One of the topics is therefore the question of the need to protect languages and cultures, and that means also the smallest ones which may be on the verge of extinction. Let us also draw your attention to literature’s role in the preservation of the memory of the cultural landscape, which has been undergoing considerable changes and in some cases may even disappear forever…[Is] literature a kind of lingua franca which could and should contribute to a better mutual understanding and insight into the different cultures and nations that sustain cultural diversity?…”[cont]

August 14, 2020: PEN Journey 38: PEN’s Work On the Road in Kyrgyzstan and Ghana

There have been a number of conferences and a few Congresses in PEN I’ve regretted not being able to attend. One was the Women’s Committee conference June 2005 in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan right after the 71st Bled Congress. As International Secretary, I have notes and reports from that conference. Nine years later in the fall of 2014, PEN held its 80th World Congress in Bishkek, a Congress I did attend. The Women Writers Committee led the way for International PEN into Central Asia. Later in 2005 members of the Women Writers Committee also met at the International PEN conference in Ghana which I did attend.

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, site of PEN International’s Women Writers Meeting in June 2005 and Accra, Ghana, site of PEN International’s African conference and also meeting of African women writers, November 2005.

First, Bishkek: The President of Bishkek PEN Vera Tokombaeva was concerned about the circumstances of writers in Central Asia since the breakup of the Soviet Union. She suggested to the new Women Writers Committee (IPWWC) chair Judith Buckrich that PEN hold a women writers meeting in Bishkek. Many of the institutions which had enabled writers to publish had vanished, and the status of women in the region had grown worse. Young writers from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan who were members of the PEN center were troubled by the decrease in the number of women working creatively. Only a handful were left.

PEN Women Writers Committee Chair Dr. Judith Buckrich and International PEN Board member Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN)

Bishkek PEN did a study highlighting the problem. Central Asian women writers were struggling with poverty, it said, and literature was no longer published unless self-published with limited distribution.

“Women writers are now mostly on their own. They have fallen into a cultural vacuum,” the conference proposal noted. “They are not in contact with colleagues outside their own country and know nothing of the state of culture in the world. In the meantime the global community has begun to pay attention to Central Asia because its difficult geopolitical situation could lead to the rise of violent, ultra-religious and fundamentalist ideologies into the area. And it is partly the lack of modern local literature that makes the region a breeding ground where alien ideologies can take root among young people. Flourishing modern literature could be the means to disseminate democratic ideas and social awareness….”[cont]

August 31, 2020: PEN Journey 39: Spiritus Loci—Literature as Home

[From address at Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee Conference September, 2006:]

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia.

Last year at this conference, I packed in a rush, left behind a pair of shoes, but in the process got a title for a story.

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia.

I don’t yet know what story will emerge, or maybe only this brief talk will emerge, but Macedonia makes the title work, at least to my mind. I Left My Shoes in England…that doesn’t work…I Left My Shoes in France?…No. I Left My Shoes in the United States…please. I look forward to discovering who left the shoes and what the circumstances were and most of all what Macedonia has to do with the story.

Ohrid, Macedonia, setting of PEN International Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee conference, 2006.

Exploring the conference theme spiritus loci will be part of the journey. As writers we know the power of place in literature and in our lives. The Latin term meaning the local spirit of a place is not always easily defined, but it relates to the geography, the history, the architecture and the people, who are both shaped by and shape the place. The ancient Romans thought every location had a spirit, some benign where people would live longer, happier lives and some evil and destructive of human well-being.

Today in a world grown smaller and more connected by jet travel, the internet, the global village, the cyber global village, with the blending of cultures and commerce worldwide, spiritus loci is perhaps a more fluid concept and to a younger generation, even a digital concept. On the internet I discovered a recording studio with the name Spiritus Loci; it moved from place to place recording people’s music wherever the musicians felt most comfortable.

Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) Dimitar Basevski (President Macedonian PEN), and Kata Kulavkova (Macedonian PEN & Chair PEN International’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

It is still the writer who can best capture a place and a people and render that spiritus loci for the reader. The best writers unveil the unity between location and character so that the writer’s version becomes the backdrop for understanding the place for generations to come, whether it be Tolstoy’s Russia, Balzac’s France, Dickens’ England, Achebe’s Nigeria, Toer’s Indonesia, Fuentes’ Mexico….[cont]

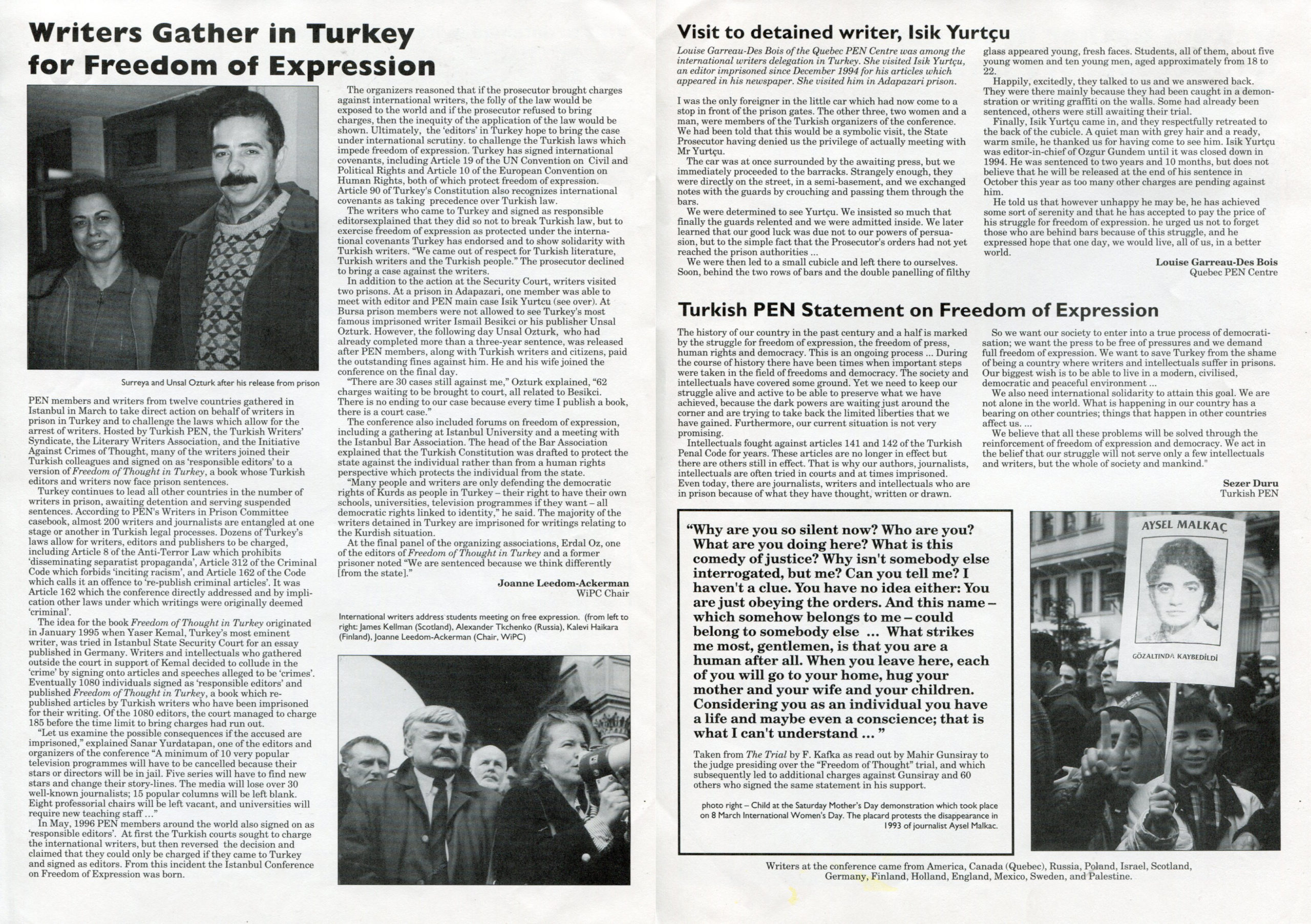

PEN Journey 19: Prison, Police and Courts in Turkey: Initiative For Freedom of Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

We sat on the ferry drinking strong Turkish coffee then handing over the emptied cups to a woman who read fortunes from the pattern of the leftover coffee grounds. As we huddled in the wind off the Sea of Marmara en route to the prison in Bursa, we speculated who among the passengers was following us. We were assured we were being followed.

Program for Initiative for Freedom of Expression Gathering, March 1997

I came to Turkey in March 1997 as the returning Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WIPC) (PEN Journey 18). I was heading a delegation of 20 PEN members from 12 countries. We’d arrived to support Turkish PEN, the Turkish Writers’ Syndicate, the Literary Writers Association and the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in the first Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression. We had signed on as “publishers” to an abridged version of the book Freedom of Expression. The original book included essays by those who were in prison or facing charges for their writing, particularly former president of Turkish PEN, the prominent novelist Yaşar Kemal. He was tried for an article he’d published in the German magazine Der Spiegel. (PEN Journey 17). Headlined “Campaign of lies,” the article called out the government for its human rights abuses, particularly its treatment of the Kurds.

Arthur Miller letter to Yaşar Kemal, March 1997

Bearing a letter from Arthur Miller, who knew Kemal and had himself come to Turkey with Harold Pinter in solidarity a dozen years before, I was among the 141 “foreign publishers” of the booklet Mini Freedom of Expression. This book contained a paragraph from each article published in the larger book. We joined the 1080 Turkish “editors” of the larger volume who included writers, theater actors, politicians, painters, cinema actors and directors, cartoonists, musicians, trade unionists, academics, lawyers, architects and others. The Turkish Penal Code made it a crime to re-publish an article that had been defined as a “crime” so that the publisher as well as the writer was charged.

The “publishers” had presented themselves before the State Security Court and faced charges of “seditious criminal activity.” After questioning the first 99 people, the prosecutor demanded the accused be tried under Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law and Article 312 on “disseminating separatist propaganda.” After six months only 185 of these individuals had been questioned and brought to trial. If these individuals were given the usual 20-month jail sentence, that would mean ten popular television programs would have to be canceled because their stars or directors would be in prison; five series would have to find new stars and change their story lines. The media would lose over 30 well-known journalists; 15 popular columns would be left blank. Eight professorial chairs would be left vacant, and universities would require new teaching staff. Theater stages and film sets would require many other artists, directors, musicians, etc., and 20 new books about prison life would be added to literature if every author wrote.

Turkey already had over 200 writers either in prison or entangled in legal processes, more than any other country. This protest initiative was unique and creative. The challenge to the court was to bring charges against so many. The State Prosecutor had dropped charges against the foreign participants on the grounds that he wasn’t able to bring us to Istanbul for questioning though the Turkish citizens who had prepared and distributed the booklet could be tried. The organizer of the initiative Şanar Yurdatapan suggested we come to Istanbul and challenge the prosecutor. Though PEN members were willing to come to support their Turkish colleagues, no one wanted to end up in a Turkish prison.

“No one will go to prison,” Şanar assured. The prosecutor had to act within six months, and even in the unlikely event charges were brought, we’d go home before a trial, and there was no extradition from the US, UK and many other countries because no such “offense” existed under their laws. Unlike organizations such as Greenpeace, PEN was not a direct action organization. PEN dealt in words, protest letters, diplomacy, meetings, on occasion candlelight vigils outside embassies and stories in the media. But Şanar, who was a song writer, civic activist, not a PEN member, instinctively understood the dynamics of nonviolent direct action and understood how to get attention and make the point that the Turkish laws were unjust and unfairly administered.

On our first day, which was Women’s Day, we joined the Saturday Mothers’ rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members. The gathering had been held every Saturday for a year and a half at Galatasaray Square, ten minutes from our small hotel in Taksim. The crowd of mothers and children held pictures and signs of their loved ones, mostly Kurds, who had been taken away, assumedly by the government and likely killed. On the edges of the crowd police in riot gear gathered but didn’t interfere. Meeting at Galatasaray Square is now banned for Saturday Mothers by the Ministry of Interior since August 25, 2018. They still keep the rally at Human Rights Association branch in one of the back streets.

Saturday Mother’s Rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members.

From there a number of us went to a women’s rally where hundreds of Kurdish women in traditional dress marched with banners shouting, “We are mothers; we are for peace! Mafia is in Parliament; students are in prison.” Along the route men cheered and dozens of police lined the road frisking and checking bags. This was the last weekend of a 40-day protest all over Turkey. At 9pm every night people around the country turned out their lights or blinked their lights and shouted out their windows and in the street, “Go Away!” in protest over the government. The idea was that people would have one minute of darkness to get years of light. At dinner that Saturday evening we watched as the streets filled with shouting and the lights in restaurant blinked on and off.

Women’s Day march of Kurdish women with police positioned along the route.

The trip to Istanbul was my first of what would turn out to be dozens of visits to Turkey over the years for PEN, for other organizations, and for family. In 1997 the times were tense; soldiers with their weapons and machine guns were stationed at the airport; armed police were on the streets; we were followed; the phones at the hotel were likely tapped. It was difficult to imagine then that it would get much better in the following decade as it did and then much worse in recent years. I’m not sure today we could hold such a gathering with confidence.

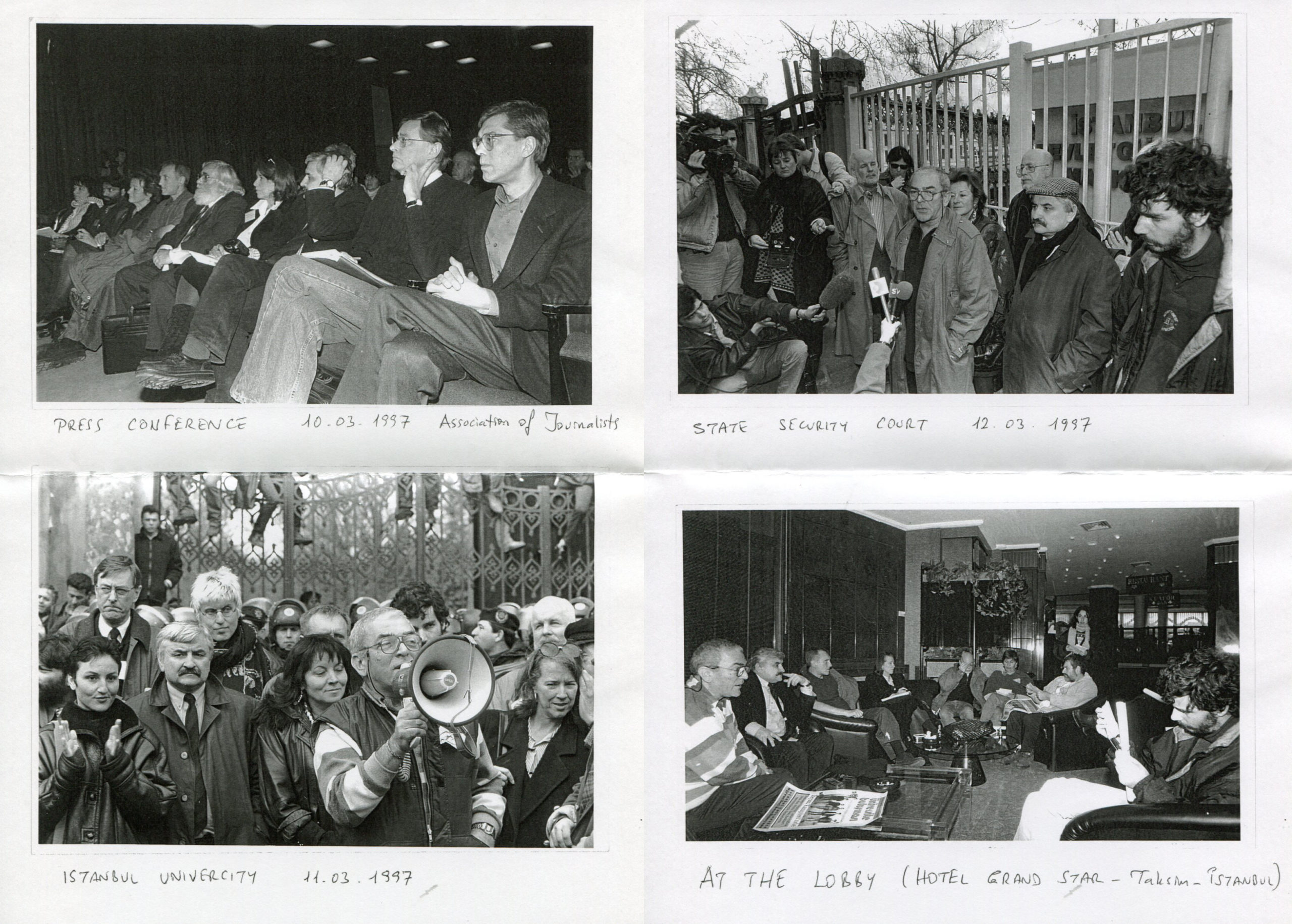

Throughout our visit we were covered by the press, including two visits to the State Security Court. In 1997 the legal way to meet publicly was to hold a press conference so we spent our days in press conferences, including one at the Journalists Association. Because I was Chair of the WiPC, I was often the one explaining why we were there. I emphasized that we had come out of respect for Turkish literature and writers. We had not come to break Turkish laws; we did not consider editing a book a crime. We were there to uphold the international covenants that Turkey had signed, approved and became a party to: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 19), Article 19 of the UN Convention on Civil and Political Rights and Article 90 in the European Convention on Human Rights. We noted that Article 90 in Turkey’s own Constitution declared that no law should supersede these international covenants.

Our PEN delegation included representatives from Canada (Quebec), Finland, Germany, Holland, Israel, Mexico, Palestine, Russia, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States and Turkey. The delegates included James Kelman, Booker Prize winner from Scotland and Turkish writers including Yaşar Kemal, Orhan Pamuk and others.

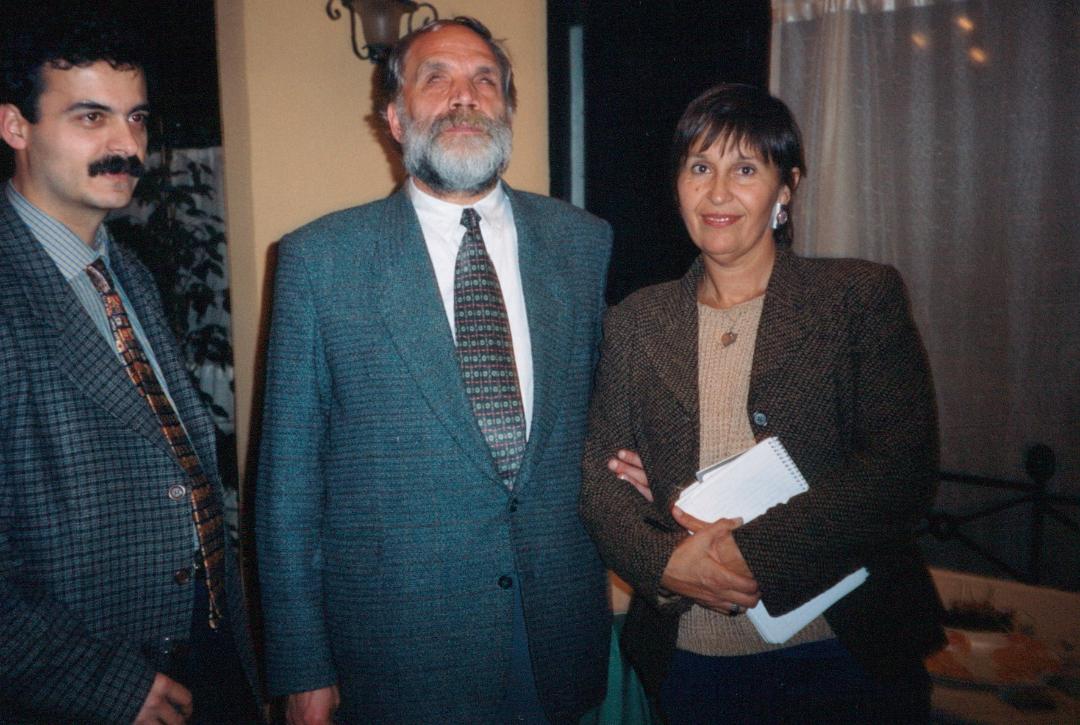

PEN members from 12 countries join Turkish colleagues for dinner at the first Gathering of the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in Istanbul, March 1997

On Monday we started the day at the State Security Court where Şanar petitioned the prosecutor for an appointment to question one delegate who had to leave early. Because the prosecutor didn’t want to bring charges against “international editors”, an act that would bring international attention, the “Turkish editors” could use this failure as further evidence of the unfair nature and application of the law when they took the case to the World Court. We approached the State Security Court again on Wednesday, when the prosecutor actually locked the gates and wouldn’t see any representative of our group. In the end nine of us—from USA, England, Scotland, Finland, Holland, Sweden, Canada (Quebec), Mexico and Russia—signed a form which said, “I accepted to be one of the collective publishers of this book willingly and I am aware of the legal responsibility. I have nothing else to say.” These forms were then sent registered mail to the prosecutor.

Two small groups visited prisons and the prisoners of conscience, including Dr. İsmail Beşikçi and his publisher Ünsal Öztürk in Bursa and journalist Işık Yurtçu in Adapazarı prison. Louise Gareau-Des Bois from Quebec PEN went to the Adapazari prison and was able to visit with Işık Yurtçu.

Kalevi Haikara from Finland and I went with Şanar on the ferry to the prison in Bursa where we met Ünsal Öztürk’s wife Süreyya. We waited and waited and talked together in the bleak courtyard with grey concrete walls rising around us topped with barbed wire, with guard towers looming over us. We went to the pink concrete building of Bursa Prison with a shield on the door “Ministry of Justice Bursa Special Prison” and waited there too. But we were not allowed to see İsmail Beşikçi, the noted Turkish sociologist and philosopher who wrote about the Kurds history and living conditions. He was one of the few non-Kurdish writers in Turkey speaking out about the treatment of the Kurds. At the time he was also one of the longest serving prisoners. He’d been sentenced to over 100 years though he was released from jail two years after our visit. Of his 36 books, 32 were banned in Turkey.

Kalevi Haikara from Finish PEN and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, WiPC Chair and member American PEN outside prison in Bursa, along with Süreyya, wife of prisoner Ünsal Öztürk (middle picture) and in conversation at Bursa Prison (far right picture.)

We were also not allowed to see Ünsal Öztürk, Beşikçi’s publisher, who had completed more than a three-year sentence. We met with the press which had gathered. We paid the outstanding fine against Öztürk with funds raised from Turkish writers, artists and many of the visiting PEN members. Öztürk was released the following day though there remained 30 outstanding cases against him, 62 charges waiting to be brought to court, all relating to Beşikçi. Every time he published a book, a charge was brought, but he kept publishing. Öztürk and his wife joined the conference.

The following day we attended the Justice House hearing of the “Kafka Trial.” When one editor of the Freedom of Expression book—actor Mahir Günşiray—faced the judges, he’d read a paragraph from Kafka’s The Trial. The paragraph offended the judges, and they brought a civil suit against him. Sixty-five other writers and artists signed on and said they also endorsed the reading of Kafka and should thus be guilty too. We all piled into the small room where the defendant Mahir Günşiray and his lawyer and the judge met. The hearing was the second or third for him, but with the room full of observers, the judge again postponed the proceedings.

At hearing of “Kafka Trial” in the Justice House

Many of us went next to Istanbul University to participate in a Forum on Freedom of Expression. However when we arrived, hundreds of students were protesting in the plaza, surrounded by riot police with shields. The situation was tense. In Ankara students had recently been arrested after they’d unfurled a banner in Parliament challenging the 300% tuition increase at state universities. The student protesters there were tried with the demand of 18-year prison sentences. The students at Istanbul University asked if we would speak at the rally. None of us were prepared for this potentially explosive scene. The writers who’d come to speak on freedom of expression asked me to talk for the group, all except Sascha from Russian PEN who also wanted to speak. Sascha, Şanar and I addressed the crowd. I emphasized that we were there to uphold the right for free expression, not to take a side with any particular party of government or to take sides on how education was financed in Turkey, but to insist that individuals should have the right to discuss, debate and write about these issues without facing prison terms. We urged that the protest stay nonviolent. We were then ushered out through the police corridor.

Rally at Istanbul University (Includes Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN), James Kelman (Scottish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Kalevi Haikara (Finish PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (WiPC Chair/American PEN), Hanan Awwad (Palestinian PEN), Turkish writer Vedat Türkali, and Şanar Yurdatapan (with bullhorn).

In the evening the Istanbul Bar Association hosted us. The head of the Bar noted that the Turkish Constitution protects the state against the individual rather than the other way around as in the US. Everyone agreed there was free expression in many quarters of Turkey, but that the danger arose when one addressed Kurdish issues and Kurdish separatism and referred to the PKK.

Attending the meeting was the former PEN main case Eşber Yağmurdereli, a blind poet/dramatist, who’d served 14 years in prison. Released August 1991, he’d spoken in September 1991 at a meeting on behalf of Kurdish prisoners and had new charges brought against him. After five years he was still awaiting the resolution of that case. His passport had been taken from him. He could be sent back to prison for more than 20 years. He said he was unable to write, and if he wrote, he had to hide the writing and not publish. He earned his living now as a lawyer.

Meeting with Istanbul Bar Association. Eşber Yağmurdereli (middle) and Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN) on right.

I also met the young brother of Bülent Balta, an investigation case. Balta, a chemistry honors graduate, a Turk, not a Kurd, had agreed to edit Özgür Gündem, the Kurdish newspaper, because of his sympathies for the difficulty of the Kurds. He had no particular experience as an editor, and after only 11 days was arrested and was serving a four-year prison sentence.

That evening the protest at Istanbul University was all over the news, including pictures of me with a bull horn speaking, but my words had been translated into Turkish so I had no clear idea what it was reported I was saying.

Early the next morning I slipped out of our hotel and walked to a large international hotel nearby where I called home. I asked my husband to confirm my return flight the following day. He asked what the flight was, but I told him to check with the travel agent and confirm. Over the phone I didn’t want to give flight details. I told him what was happening, including the widespread coverage of the protest with my participation, and he told me a colleague in Washington said that the American Embassy knew I was there and warned me not to leave the hotel. I had to leave the hotel, I explained. I was leading the delegation and events were planned, including a farewell dinner on the Bosphorus.

At the final panel/press conference, I noted that I had two sons, and as I observed the young people here, especially the young police officers and the young students, I felt sorrow that these youth were set across battle lines from each other. There was so much talent and promise we had seen. For the first time in the three days of speeches and press conferences, emotion stirred in my voice and I paused for a moment. One of the headlines the following day read something to the effect: “She Cries for Turkey!”

Panel at Initiative for Freedom of Expression Conference, Istanbul March, 1997

The following morning I was to be driven to the airport, but the driver didn’t show up, and I was left to find my own transportation in a taxi. The atmosphere around the conference had slowly made each of us cautious, even slightly paranoid. As I climbed into the taxi, driven by a stranger, I remembered the fortune teller on the ferry a few days before. Proceed with caution…was that her warning? You will make friends…was that the prediction? The road ahead is fortuitous but also fraught? In fact, I no longer remembered what her fortunes were, and I didn’t believe in fortunes or scattered coffee grounds, but I left Istanbul with a strong belief in the people and a commitment to the country and to the writers and publishers and lawyers and journalists and to the young people I had met and to the promise they represented.

In years following I returned to Turkey on numerous missions for PEN and for meetings with Human Rights Watch, with the International Crisis Group, on a trip with UNHCR looking at the Syrian refugee crisis, and several trips with my oldest son who wrestled in the World Championships and European Championships in Ankara and in the World Championships again in Istanbul and also lectured in mathematics at Koc University and other universities and with my youngest son who lived in Istanbul for two years with his two young children and wrote as a journalist on the Turkish/Syrian border and has set two of his four published novels in Turkey.

PEN International Writers in Prison Committee Centre to Centre newsletter special Turkey section April 1997

Next Installment: PEN Journey 20: Edinburgh—PEN on the Move, Changes Ahead

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference, March 2005

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through 141 centers in 99 countries. They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see this ancient city for himself, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together. –Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International

Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression

(Below is my talk for the Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression, a conference held every two years, but this year it is being held via video May 26-27. For the first time in 21 years the organizers judged that a gathering in person was too problematic given the arrests and crackdowns on the media. Turkish presidential elections are scheduled for June 24 alongside parliamentary elections.)

I first visited Turkey for the inaugural “Gathering in Istanbul” in March, 1997. At the time I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee and joined 21 other writers from around the world. Along with over a thousand Turkish artists and writers, most of us had signed on to be “publishers” for Freedom of Thought, a book that re-issued writings which had violated Turkey’s laws against “insulting the State.” The book included work by noted authors, including celebrated novelist Yasar Kemal. None of us aspired to go to Turkish prison, but we understood the importance of showing up and showing solidarity with our Turkish colleagues. During that Gathering we visited prisons where writers and publishers were incarcerated and visited court rooms where they were charged.

Inaugural “Gathering in Istanbul” March 1997

In the subsequent decade, conditions for writers in Turkey improved. An amnesty released writers from prison; oppressive legislation was rescinded though new laws replaced old articles in the penal code. But the climate opened. We all took hope that Turkey might signal an opening of consciousness and an easing of political and legal constraints globally.

Unfortunately, that opening has closed, and we are here today on video because the biennial ‘Gathering in Istanbul’ for the first time in 21 years is too problematic to hold in Istanbul. The situation for freedom of expression is worse than ever in Turkey with more writers in prison than anywhere else in the world. Depending on the statistics of the day, there are more than 250 journalists and media workers in or facing prison terms, 200 media outlets closed, and thousands of academics and civil servants let go or facing charges.

Yet we are here, even if on video. And the organizers remain steadfast in Turkey. I take heart in the commitment of individuals who understand that freedom of expression is central to a free society and work towards that end.

For this “Gathering in Istanbul” it was suggested we look at “Freedom of Expression Around the World,” not just in Turkey. My general observation is that the world is reversing direction from those days 20 years ago when many thought authoritarianism was yielding globally to democracy and freedom.

The situation in my own country, the United States., is as fraught as it has ever been in my lifetime in the relationship between the government and the media, but the press is protected by the U.S. Constitution, laws, history and society. The majority of U.S. citizens still remain committed to protect freedom of expression and to remain vigilant though sometimes I fear we are preoccupied with our own challenges to the exclusion of more dire challenges to free expression around the world. I also fear we have lost credibility and impact when speaking out on these issues. Yet as an American, I can hold vigils in front of prisons, sit in courtrooms, write articles and books, meet Ministers, and then return home. I’m able to write and to speak out without being threatened with imprisonment or death.

I’d like to focus the rest of my talk on the courageous writers in the Democracy Movement in China, especially after the death of Liu Xiaobo, Nobel Peace laureate who died last July in prison after serving nine years of an eleven-year sentence for “inciting subversion of state power” because of his participation in the drafting and circulating of Charter 08. I have the privilege of being an editor for the English-language edition of The Memorial Collection of Liu Xiaobo. The collection includes writings from dozens of Liu’s colleagues inside and outside China, who knew him and pay tribute to the man, his ideas and to the consequential voice he had in articulating and taking action on behalf of a free society.

One of the authors of Charter ’08, a document signed by hundreds of Chinese writers, intellectuals and citizens, Liu Xiaobo and others set out a democratic vision and path for China, using rule of law and consensus, not weapons and violence. It is individuals like Liu Xiaobo and his fellow Chinese writers and thinkers, who one hopes will eventually prevail. Like the writers and thinkers in Turkey, they are committed to ideas, to the rule of just laws and to nonviolent means to bring about change and wrest society from tyrannical modes.

Liu Xiaobo understood that a free society begins with the individual consciousness. In his Final Statement “I Have No Enemies” he addressed the court:

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people. It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to progress of our country to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

Such sentiment was difficult for many to accept, especially after he died. Many questioned whether he would have expressed the same sentiments had he known his end. I’ve been assured by those who knew him well that he would have stood by this statement. His commitment was rooted in his view of himself and of what it would take to change society.

A longtime colleague Cui Weiping has observed that Liu Xiaobo “…viewed the world through boundaries of his own making. Whatever he wouldn’t allow into his life, he was also unwilling to allow into the world. For instance, if he didn’t have violent tendencies in his own life, he would not let the behavior of others impose on him. If he valued freedom and autonomy, he would not become mired in hatred because of the crimes of others, since hateful people were dominated by the other side. If he experienced the good things and positive feelings of human life, he knew all the more that he must allow what was good and open to take root in himself and not what was biased and narrow-minded. His life was oriented toward love and light, not toward hatred and darkness. This was his own decision and what he was willing to take upon himself; every person writes his own history. Other people could choose to go along with Xiaobo or advance alongside of him, but there was no need to feel that this was his error or flaw that must be corrected or surmounted. Twenty years passed like a day, and he was a trailblazer for people who insisted on their own ideas. China lacks trailblazers like Xiaobo, and that is what allowed him to become a standard-bearer for the Chinese Democracy Movement and gain the widespread endorsement of the international community.”

A small number of Chinese writers drafted Charter 08, thousands of citizens have signed it, but only one went to prison and died.

No one knows and few can predict the success of Charter 08’s vision and the ultimate impact of Liu Xiaobo, but history has a long arc and may well bend to those who see our common humanity and the universal value of freedom for the individual. By focusing on the individual’s responsibility for his own behavior and consciousness, Liu offered the tools to empower all, for no government has the mandate over one’s individual consciousness. There the individual sets his or her own terms of engagement with the world.

In reading the essays of the many Chinese writers who knew and admired Liu Xiaobo and his vision, I also think of Turkish writers and artists I have had the privilege to know over the years who continue to work towards a free society.

The two countries and circumstances are different, and many would say Turkey is not as extreme as China, but in all the years I have been working with PEN, it was Turkey and China which placed the most writers under pressure. In China the sentences were often longer and harsher, but the numbers were greater in Turkey. But in both nations the individual voices of writers, publishers and artists continue to inspire.

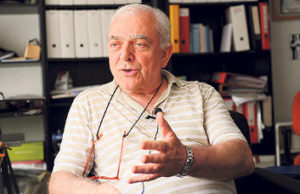

Hope for Songs Not Prison in 2017

The last time I saw Şanar Yurdatapan we had coffee in the press building in Istanbul after Human Rights Watch released its 2016 World Report “Politics of Fear and the Crushing of Civil Society”. I’ve known Şanar for almost 20 years, ever since I headed PEN International’s delegation for his first Initiative for Free Expression in Istanbul in 1997.

A noted and popular musician and song writer, Şanar has dedicated the last decades to defending and trying to open up space in Turkey for free expression. He’s done so by monitoring, reporting and organizing on behalf of writers and artists under threat. At our coffee a year ago he told me he was retiring, or at least going back to song writing and handing over the mantle of leadership to the younger generation.

However, in the past year freedom of expression has been under siege in Turkey with 150-170 writers and journalists now in prison and hundreds of news organizations closed down. This past week Şanar was called before prosecutors for his advocacy on behalf of the closed newspaper Özgür Gündem, (Turkish for “Free Agenda”), the chief newspaper read by Kurds.

“It is both the duty and the right of a journalist to report; his is freedom of information at the same time and right to freedom and right of all of us,” Şanar is reported to have told the court.

At the end of the hearing the prosecutor demanded that Şanar be imprisoned for over ten years for “propaganda for the organization” under the Anti-Terror Law. The hearing is January 13, 2017. Şanar is now 75.

Since the failed coup in July the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has increased the detainment and arrest of writers, journalists and academics for their peaceful opposition to his policies. These have included noted novelist Asli Erdoğan and leading linguist Necmiye Alpay, who spent her 70th birthday in detention. Brothers Ahmet Altan, a novelist, and Mehmet Altan, an academic, are held in maximum security Silivri prison facing terror charges, unable to receive books, letters or any communication from outside or to visit the prison library.

As the year 2016 ends with an increase of terror attacks around the world, with a new administration about to take power in the U.S., with existing administrations struggling to hold onto power in Europe, with a collapsing Syria and a continual tide of refugees around the world, with an odd dance between super powers and aspiring super powers, the single citizen voice can get overlooked. But history has shown that when the individual voice, especially those of writers who dissent, gets stifled, the arc of history is bending towards conflict and away from peace which leaders and citizens say they want.

In the new year PEN International hopes to go to Turkey to add support firsthand for Turkish writers and for the important role they play right now in keeping that arc from bending too far backwards. We will watch and argue for the fate of Şanar and others and hope that he will be writing songs in the years ahead, and not from prison.

View on the Bosphorus: Rights in Retreat

I’m sitting on the Bosphorus today in Istanbul looking across to the Asian side over the balustrade of a European porch. I’ve been visiting Istanbul over the last 20 years for conferences, recently for visits to refugee camps and most often now to see family living here. Istanbul is one of my favorite cities, full of heart, multiple cultures, history and citizens of intellect and warmth.