Posts Tagged ‘PEN Myanmar’

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

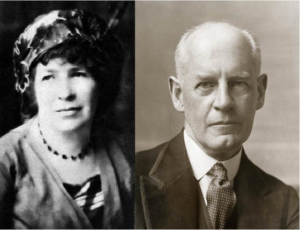

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

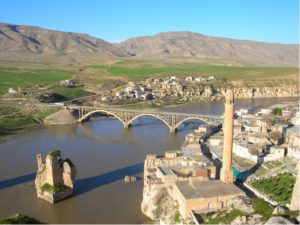

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference, March 2005

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through 141 centers in 99 countries. They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see this ancient city for himself, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together. –Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International

Parallel Universe in a Glassed Concert Hall in Iceland

If you want to understand politics—it’s like being in a book club where everyone discusses the grammar.

So said actor/comedian Jon Gnarr, Mayor of Reykjavik, Iceland when he addressed the recent 79th PEN International Congress. Gnarr was elected Mayor in 2010 from the Best Party, which he and friends with no background in politics created as a satirical party after the economic meltdown in Iceland a few years ago. They won over a third of the seats on the City Council with a platform that included free towels in all swimming pools, a polar bear for the zoo and “all kinds of things for weaklings.” After he was elected, Gnarr declared he wouldn’t form a coalition government with anyone who hadn’t watched the TV series The Wire.

The politician with a short black tie, a sense of humor and a view of politics as a parallel universe resonated with the audience of over 200 writers at the Opening Ceremonies of the PEN Congress. Writers from 70 centers of PEN gathered to deliberate and debate literature and the situation for writers and freedom of expression around the world, a world they agreed often bordered on the absurd, but the absurd with serious consequences.

The Assembly discussed and passed resolutions on the challenges to freedom of expression in countries including Mexico, China, Cuba, Vietnam, North Korea, Eritrea, Belarus, Syria, Egypt, Turkey, Tibet, and Russia. The delegates walked en masse to the Russian Embassy to present their resolution protesting the recent legislation on blasphemy and “gay propaganda.” And they applauded the announcement during the Congress of the release of Chinese poet Shi Tao 15 months before the end of his 10-year sentence.

“Shi Tao has been one of our main cases since his arrest in 2004, an honorary member of a dozen PEN centers and one of the first and most significant digital media cases,” said Marian Botsford Fraser, Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. “Shi Tao’s arrest and imprisonment, because of the actions of Yahoo China, signaled a decade ago the challenges to freedom of expression of internet surveillance and privacy that we are now dealing with.”

The delegates challenged the secret surveillance of citizens recently uncovered in the United States and the United Kingdom and the prosecution of those who revealed programs violating international human rights norms.

“As an organization dedicated to preserving free expression and creative freedom, PEN is particularly troubled by recent revelations concerning the nature and scope of electronic surveillance programmes in use by the United States’ National Security Agency and parallel programmes such as those being carried out by the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in the United Kingdom. As leaks about the U.S. government’s PRISM programme, the U.K. governments Tempora programme, and other such programmes make clear, certain governments now possess the capacity to monitor the private telephone, internet and other digital communications of every citizen on earth—among them, the communications of PEN’s 20,000 members worldwide.”

In this parallel universe one of the new centers PEN elected at the Congress was the PEN Center of Myanmar. PEN Myanmar will be an early citizens’ organization there defending writers and civil society in a country that just a few years ago was one of the most closed societies on earth. Also sitting in the glassed waterfront Concert Hall among the Assembly of Delegates were North Korean writers who now meet as an exile center of PEN, but as voices stir and comedians and actors and politicians mingle, who knows the universe that may yet emerge?