Posts Tagged ‘Nobel Laureate’

Peace: Fabric with a Million Threads

Earlier this summer I had the opportunity to moderate a panel of high school teachers at the United States Institute of Peace called “A Year in the Life of a Peace Teacher.”

United States Institute of Peace in Washington, DC

On that morning of July 10 two positive news events broke: the final young soccer players and their coach, who had been trapped for almost two weeks, made it out of the caves in Thailand. And Liu Xia, wife of Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese Nobel Peace Laureate who died last year in custody, landed in Europe, released after a decade of virtual house arrest in China.

For me these events connected to the panel on the teaching of peace-building.

Was peace possible? Could peace be “built”? The answer we concluded that morning with cautious optimism was: Yes.

The miraculous rescue of the soccer team resulted because highly skilled citizens from nations around the world, including the U.S., Australia, Denmark, Britain, China and most importantly Thailand came together and exerted their best efforts with a common goal everyone agreed on.

Freedom for Liu Xia resulted in large part because citizens and politicians around the world spoke up and advocated on her behalf though a similar effort had not won the release of her husband.

That morning, listening to the teachers and their work with students reinforced a view that peace was not just building bridges between two opposing pylons or signing treaties, but was the weaving of hundreds, thousands, millions of threads, of each citizen taking responsibility within his/her own community.

Each year the U.S. Institute of Peace, founded in 1984 as a nonpartisan Institute to promote peace and resolution of conflicts around the world, also focuses on the U.S. and selects four high school teachers for year-long training which they take into their classrooms. They work on problem-solving and peace-building in their communities and also study global peace opportunities.

This year’s teachers from Missouri, Montana, Florida and Oklahoma shared ways they and their students ignited discussion in their classrooms and in their communities and then took initiatives relating to issues of race, immigration, etc. They emphasized the understanding that peace didn’t mean avoiding conflict but rather finding ways to engage nonviolently and then to find ways to resolve conflicts by listening, determining the interests of the other, showing empathy.

Specific stories of the teachers and their journeys with their students can be heard on this link.

To conclude the panel it was appropriate to quote Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo. In his career and in his final statement to the court before he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for his writing and work towards democracy, he told the judge: “I have no enemies and no hatred.” In his life Liu explained that to build a society without hate, one had to begin with one’s self. After he died in custody last year, many questioned whether he would have claimed this had he known his end, but those who knew him well said he would have because he believed the responsibility for a peaceful and fair society began with oneself.

Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people… It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, it can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.

It was poignant and fitting that day to see Liu Xiaobo’s wife Liu Xia’s smile as she landed in Helsinki.

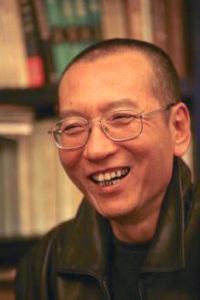

Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo died this past July in prison, where he was serving an 11-year sentence for his role in drafting Charter ’08 calling for democratic reform in China. Below is my essay in The Memorial Collection for Dr. Liu Xiaobo, just published by the Institute for China’s Democratic Transition and Democratic China.

I never met Liu Xiaobo, but his words and life touch and inspire me. His ideas live beyond his physical body though I am among the many who wish he survived to help develop and lead democratic reform in China, a nation and people he was devoted to.

Liu’s Final Statement: I Have No Enemies delivered December 23, 2009 to the judge sentencing him stands beside important texts which inspire and help frame society as Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail did in my country. King addressed fellow clergymen and also his prosecutors, judges and the citizens of America in its struggle to realize a more perfect democracy.

I hesitate to project too much onto Liu Xiaobo, this man I never met, but as a writer and an activist through PEN on behalf of writers whose words set the powers of state against them, I can offer my own context and measurement.

Liu said June, 1989 was a turning point in his life as he returned to China to join the protests of the democracy movement. In June, 1989 I was President of PEN Center USA West. It was a tumultuous year in which the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was issued in February, and PEN, including our center, mobilized worldwide in protest.

In May, 1989 I was a delegate to the PEN Congress in Maastricht, Netherlands where PEN Center USA West presented to the Assembly of Delegates a resolution on behalf of imprisoned writers in China, including Wei Jingsheng, and called on the Chinese government to release them. The Chinese delegation, which represented the government’s perspective more than PEN’s, argued against the resolution. Poet Bei Dao, who was a guest of the Congress, stood and defended our resolution with Taipei PEN translating.

When the events of Tiananmen Square erupted a few weeks later, my first concern was whether Bei Dao was safe. It turns out he had not yet returned to China and never did. PEN Center USA West, along with PEN Centers around the world, began going through the names of Chinese writers taken into custody so we might intervene. I remember well reading through these names written in Chinese sent from PEN’s London headquarters and trying to sort them and get them translated. Liu Xiaobo, I am certain must have been among them, though I didn’t know him at the time.

In his Final Statement to the Court twenty years later, Liu told the consequence for him of being found guilty of “the crime of spreading and inciting counterrevolution” at the Tiananmen protest: “I found myself separate from my beloved lectern and no longer able to publish my writing or give public talks inside China. Merely for expressing different political views and for joining a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher lost his right to teach, a writer lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual could no longer speak openly. Whether we view this as my own fate or as the fate of a China after thirty years of ‘reform and opening,’ it is truly a sad fate.”

I finally did meet Wei Jingsheng after years of working on his case. He was released and came to the United States where we shared a meal together at the Old Ebbit Grill in Washington. I was hopeful I might someday also get to meet Liu Xiaobo, or if not meet him physically, at least get to hear more from him through his poetry and prose.

His words are now our only meeting place. His writing is robust and full of truth about the human spirit, individually and collectively as citizens form the body politic. I expect that both his poetry and the famed Charter 08, for which he was one of the primary drafters and which more than 2000 Chinese citizens endorsed, will resonate and grow in consequence.

Charter 08 set out a path to a more democratic China which I hope one day will be realized.

“The political reality, which is plain for anyone to see, is that China has many laws but no rule of law; it has a constitution but no constitutional government,” noted Charter 08. “The ruling elite continues to cling to its authoritarian power and fights off any move toward political change….

“Accordingly, and in a spirit of this duty as responsible and constructive citizens, we offer the following recommendations on national governance, citizens’ rights, and social development: a New Constitution…Separation of Powers…Legislative Democracy…an Independent Judiciary…Public Control of Public Servants…Guarantee of Human Rights…Election of Public Officials…Rural—Urban Equality…Freedom to Form Groups…Freedom to Assemble…Freedom of Expression…Freedom of Religion…Civic Education…Protection of Private Property…Financial and Tax Reform…Social Security…Protection of the Environment…a Federated Republic…Truth in Reconciliation.”

Charter 08 addresses the body politic. Liu Xiaobo’s Final Statement: I Have No Hatred addresses the individual, and for me resonates most profoundly. Its call doesn’t depend on others but on oneself for execution. He warned against hatred.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows). It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

At a recent conference a participant asked if Liu Xiaobo might have changed this statement if he understood how his life would end. A friend who knew him assured that he would not for he was committed to the idea. Liu Xiaobo’s commitment to No Enemies, No Hatred does not accede to the authoritarianism he opposed, but instead resists the negative. He aligns with benevolence and love as the power that nourishes the human spirit and ultimately allows it to flourish. Liu’s words and his ideas lived offer us all a beacon and a guide.

Two Voices Behind the Iron Doors

(In the past weeks I was brought to focus again on the situation of two writers in prison, one in China, the other in Turkey, both countries that have consistently challenged and imprisoned writers. In China the hope for expanded freedom of expression that came with the Olympics and China’s engagement with global institutions has not materialized, and Chinese writers remain in prison with long sentences. The situation in Turkey for a while was improving, but in the past year arrests have again escalated.)

Voice in China

I had dinner recently with three colleagues of Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel laureate and writer currently serving an 11-year sentence in a Chinese jail. Two of his friends, Shen Tong and the other friend arrived in the U.S. around the time of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, but the younger best-selling writer and democracy activist Yu Jie didn’t leave China until January, 2012 after being detained and tortured and put under house arrest. He now lives in Virginia.

Yu Jie consulted with Liu Xiaobo during the writing of Charter 08, the manifesto calling for democracy in China which resulted in the imprisonment of Dr. Liu. He and Liu Xiaobo also co founded the Independent Chinese PEN Center, and Yu Jie has written a biography of Liu Xiaobo.

At a round wooden table in a bustling Washington restaurant the friends outlined their campaign. Among their strategies, they are working to gather a million signatures worldwide calling for the release of Liu Xiaobo and his wife Liu Xia, who has been under house arrest since Liu’s imprisonment. So far they have gathered about half a million signatures in 130 countries, including from 135 Nobel Laureates. The Friends of Liu Xiaobo are also campaigning for the release of other prisoners of conscience in China. They and the Nobel Laureates are mobilizing support around the world and have been told the Chinese government has started to take notice and to worry about the scope of the campaign. Dr. Liu is the only Nobel Peace Prize Laureate in prison.

Here is the link to sign the petition.

* Friends of Liu Xiaobo Twitter: http://twitter.com/lxbfree,

* Facebook page: http://www.facebook.com/Free.Liu?fref=ts

Poem by Liu Xiaobo:

A Small Rat in Prison

a small rat passes through the iron bars

paces back and forth on the window ledge

the peeling walls are watching him

the blood-filled mosquitoes are watching him

he even draws the moon from the sky, silver

shadow casts down

beauty, as if in flight

a very gentryman the rat tonight

doesn’t eat nor drink nor grind his teeth

as he stares with his sly bright eyes

strolling in the moonlight

5. 26. 1999

Translated by Jeffrey Yang

Voice in Turkey

I reached into the drawer of my post box in Washington this week and pulled out a card addressed to Doame Leexa-Acker (the name no doubt a reflection of my poor penmanship on the receiving end.) The envelope was from Turkey, and the postcard inside had a picture of Diyarbakir, the ancient city in southeastern Turkey that is the capital of the Kurdish region and the hub of fighting for decades between the Army and the PKK.

In a neatly printed hand the card read:

21 March Newroz Kurdish religiots [sic[ celebrate.

1200 day not free. I’m healt [sic] bad.

I’m free about concerned. I need you children.

I at the house must be. I’ not killer!

I’m writer, lawyer, peacemaker.

I’ hope back you can be. Please.

Grand peace in the door.

Thank you for post cards 🙂

Best wishes,

Muharrem Erbey

Even with the challenge of English, the appeal resonated. I looked up his case and reminded myself of his situation: Muharrem Erbey is a writer and a human rights lawyer, Vice President of the Human Rights Association. He was imprisoned under the Anti-terror Law in 2009. According to PEN International, he has compiled reports on disappearances and extra-judicial killings in the Kurdish region and has represented individuals in the provincial, national and international courts, including the European Court of Human Rights. He was one of dozens of writers and journalists tried under the auspices of the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) trials which targeted pro-Kurdish writers, publishers, academics and translators, tried together as KCK’s “Press Wing.” He has published articles and co-edited a collection of Turkish and Kurdish language stories. His own short story collection, My Father, Aharon Usta was delayed for publication after his arrest.

Last fall Erbey wrote to those at PEN who had advocated on his behalf: “I send you my heart’s warmth from behind the iron doors and bars and damp, cold, wet walls of prison….My speeches and comments never contained words of violence.”

Circulating a writers’ work and giving voice to those silenced is part of what writers can do for each other. Below is a section of a translated letter from Erbey describing the seasons in prison with a link to the full letter:

I want to tell you how I have experienced the four seasons from behind bars.

Autumn. In the morning, as I reach over the barbed wire crowning this wall six or seven metres in height, the sun as it passes briefly through our ventilation system and away again, the sound of the sparrows that perch on the wire and fly off with the crumbs of bread we toss, the squawking of doves overhead, this sky stained a cold and faded blue, the wind that howls and carries dry fragments of grass through the ventilation – all work the ache of loneliness finely and deeply into me, as the captivity of my shivering body grows a storey higher. I am listening to the sound of the wind. The chattering of clothespegs hanging from the line, the clatter of water bottles roaming the area, flying newspaper scraps and silently wandering dreams, hopes that grow from a whisper to a roar – they strike the wall and go no further.

Winter. There is a weak sun that does not warm you. The air is cold. This place is alien to life, with its endless concrete and iron, these wire fences. The walls’ peeling grey paint, their damp, drains you of energy. Your dreams are caked in dust and soot. At 6 am, as we four men in each room wake to the metallic clank of iron doors, we wish that this were all a dream, but it is not; everything is real. As it happens, prison is the one place one would never want to be when waking. We have this privilege. The prison walls allow everything to pass, except time. I am freezing, my throat dries up, my eyes are burning, there is the weight of tonnes on top of me; it is as if I am tied in steel cord. I cough and I sneeze. In winter prison becomes a prison, and the cold season seems to go on forever. At night we go to the toilet dozens of times.

Spring. Taking root in a crack of broken concrete, seeds brought over the walls and wire by the wind display nature’s irresistible force with the unfurling of their leaves. At first glance you think that the seedling has broken its way out through the concrete. But nature stubbornly allows life to take hold, splitting concrete despite every restriction. An unimaginable aroma of oleaster surrounds us. You know that spring is here from the sound of birds and the smell of flowers. And from the flocks of birds in the sky, and its glittering blue.

Summer. The sun lays waste to it all, as walls and floor turn to a raging fire. I grow drowsy and still. As I shake my head before the spinning ventilator it rises above the walls and the wire fences and I fight to breathe, just as a fish in a tank rises to the surface and, looking desperately at the blue skies, gasps. At night the sound of a soldier whistling intermittently on the watchtower blends with an owl’s hooting. There is a wedding in the neighbouring village. The banging of drums, the women’s ululations and the barking of excited dogs plant a smile on my face just as soon as they steal in through an open window. How sweet to hear life even if we cannot see it!

If only prison did not teach one how beautiful life is. My sons Robin (10) and Robert (5) ask “Daddy, when will you be done here? How long until you come home?” I reply “Not long, not long.” In reality, I do not know when I will be done….

[Follow the links to send appeals on behalf of Liu Xiaobo and Muharrem Erbey.]