Posts Tagged ‘Charter 08’

Nobel Peace Prize for Liu Xiaobo Ten Years After

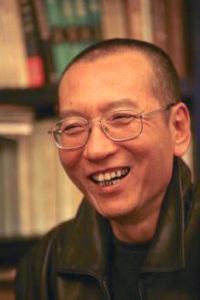

PEN International marks the ten-year anniversary of the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to writer, literary critic and human rights activist Liu Xiaobo on 10 December 2010. PEN’s Liu Xiaobo Anniversary Campaign acts as a commemoration of Liu Xiaobo’s life, his contribution to Chinese literature, and his selfless work promoting basic freedoms in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The campaign also highlights the cases of writers Gui Minhai, Kunchok Tsephel, Yang Hengjun and Qin Yongmin who are currently detained by the PRC government. The campaign seeks to raises awareness of their situation, to boost advocacy work on their behalf and to ensure that they and their families feel supported and not forgotten.

The following links to PEN’s campaign. Below is text and Chinese translation of my video tribute to Liu:

Hello, I’m Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Vice President Emeritus of PEN International.

您好!我是乔安尼•利多姆-阿克曼,国际笔会荣休副会长。

Ten years ago, essayist, poet, activist and PEN member Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace. Liu envisioned and worked towards a peaceful and democratic pathway for China. Beginning with the protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and through the subsequent decades, he spoke out and wrote and gathered people and ideas in support of a China where individual freedom was valued and protected.

十年前,散文家、诗人、活动家、笔会成员刘晓波成为首位荣获诺贝尔和平奖的中国公民。刘先生设想并致力于中国走向和平民主的道路。他从1989年天安门广场抗议运动开始,在随后数十年言说和书写,并聚集民众及理念,以支持一个重视和保护个人自由的中国。

In 2008, he and others drafted Charter 08, which set out this democratic vision. He and others gathered hundreds and then thousands of signatures from Chinese citizens who endorsed the vision. Charter 08 did not call for an overthrow of the government so much as a transformation of the way government related to its citizens in a transition to a democratic society that would include freedom of expression and assembly.

2008年,他和其他人起草了《 零八宪章》,阐明这一民主愿景。他们从支持这一愿景的中国公民那里汇集了成百上千人签名。 《零八宪章》并未呼吁推翻政府,而是要转变政府相对于公民的方式,转型为包括言论自由和集会自由的民主社会。

Liu Xiaobo has been called the Nelson Mandela or Václav Havel of China because of his ideas, his activism and his leadership. Like Havel, Liu was committed to nonviolent action as a means of achieving change, and he was an inspired writer.

刘晓波因其理念、言行和领导能力而被称为中国的曼德拉或哈维尔。像哈维尔一样,刘晓波也致力于以非暴力行动来实现变革,他是一位受鼓舞的作家。

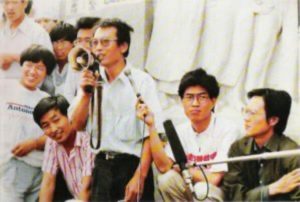

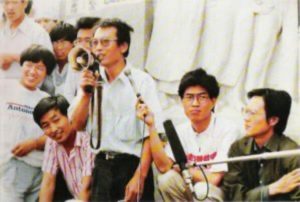

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

I first encountered Liu Xiaobo through PEN. After the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989, PEN worked on behalf of the writers who had been arrested in the protest, including Liu Xiaobo. Liu had also been instrumental in persuading students to leave the Square before the soldiers and tanks rolled in to attack and possibly kill them. At the time of Tiananmen Square, I was President of PEN Center USA West. A few years later when Liu was again imprisoned for his writing, I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee.

我首先通过笔会遭遇刘晓波。在1989年天安门广场镇压后,笔会致力于代表在抗议活动中被捕的作家,包括刘晓波。刘晓波还曾劝说学生离开广场,以免士兵和坦克席卷攻入广场可能杀死他们。在天安门广场抗议时,我担任美国西部笔会会会长。几年后,当刘晓波再次因写作而被监禁时,我是国际笔会狱中作家委员会主席。

Liu Xiaobo then went on to become one of the founders and the second President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), whose members lived inside and outside of China. He was instrumental in establishing the platforms by which these writers could communicate and share ideas about a society where freedom of expression and democratic processes could exist.

刘晓波随后成为独立中文笔会(ICPC)的创始人之一和第二任会长,该笔会成员居住在中国境内和海外。他发挥作用建立起这个平台,这些作家们可以借此平台,交流和分享有关这样一个社会的理念,在那里言论自由和民主进程得以存在。

During the time Liu was President of ICPC, I was the International Secretary of PEN. However, Liu was not allowed out of mainland China into Hong Kong where ICPC had its meetings, and I didn’t get to the mainland until in 2010 after he was arrested for the fourth and final time, so we never met in person, though over decades I have worked with many of his colleagues.

在刘晓波担任独立中文笔会会长期间,我曾担任国际笔会秘书长。然而,他没获准离开中国大陆前往独立中文笔会举行会议的香港,而直到他 第四次也是最后一次被捕后的2010年,我才去中国大陆,因此我们从未亲身见面,尽管数十年来我一直与他的许多同事共同工作。

Liu Xiaobo was the writer the Chinese government feared the most and therefore arrested. Liu was charged as “an enemy of the state” for “incitement of subverting state power” because of his ideas, his writing and his participation in the drafting and circulating of Charter 08. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison. He was the only recipient of the Nobel Prize who was in prison at the time and not allowed to attend the ceremony. Only an empty chair represented him. His wife Liu Xia was also not allowed to attend. Liu Xiaobo died in custody July 13, 2017.

刘晓波是中国政府最害怕的作家,因此而被捕。由于其理念、写作并参与起草和传播《 零八宪章》,刘晓波被指控为“煽动颠覆国家政权”的“国家敌人”。他被判处了十一年徒刑。他是当时在监狱中而未被允许参加颁奖典礼的唯一诺贝尔奖得主,只有一把空椅子代表他。他的妻子刘霞也被禁止出席。刘晓波于2017年7月13日去世。

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

他去世后,全世界了解他的作家开始书写他及其作品,书写中国以及自由主义和民主理想之路。今年出版了《刘晓波之旅程:从黑马到诺奖得主》(文文版),包含75篇以上的文章,可能是来自中国民主活动人士的最大笔墨聚会,既是对刘晓波的回忆致敬,也是对中国民主运动的研究。

China’s Democracy Movement and Liu Xiaobo’s legacy still inspire those inside and outside of China, from the mainland to Xinjiang to Tibet to Hong Kong and to neighboring countries engaged in the struggle for political reform and an end to authoritarian rule.

中国民主运动和刘晓波的遗产,仍然激励着中国内外的人们,从大陆到新疆,到西藏,再到香港,再到争取政治改革和结束专制统治的邻国。

Some have said that because of China’s ascendency in the last decade, the legacy of Liu Xiaobo has been reduced to nothing. But a longer view of history shows that the same was said of those visionaries and martyrs for free societies in Eastern Europe and South Africa.

有人说,由于近十年来的中国崛起,刘晓波的遗产被削减为零。然而,更长的历史证明,同样的说法也曾针对过那些在东欧和南非争取自由社会的远见者和烈士们。

Societies move forward and are changed by ideas, by leaders, and ultimately by their citizens. Liu Xiaobo did not aspire to personal power, but those in power came to fear him because he understood how to move ideas into action.

社会向前发展,并通过理念、领导者及最终通过其公民而改变。刘晓波并不渴望个人权力,但是当权者却开始害怕他,正因为他知道如何将理念付诸行动。

As individuals one by one—be they writers, lawyers, academics or others—are put into prison and taken out of the discourse, those in power attempt to maintain their control. That is why it is important to keep an eye not only on the monolith of regimes and government, but to protect the individuals who hold the powerful to account.

当作家、律师、学者或其他人一个接一个地被关进监狱并从话语中带走时,当权者试图维持其控制。这就是为什么重要的不仅是着眼于政权的垄断和政府问题,而且要保护那些向当权者追责的个人。

Liu Xiaobo declared, “Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth.”

刘晓波声言:“表达自由,人权之基,人性之本,真理之母。”

Liu Xiaobo insisted that to transition to a state that one wanted to live in, one needed to have citizens who represented those values even in the struggle.

刘晓波坚持认为,要过渡到一个人们想要生活的国度,就需要有即使在斗争中也代表那些价值观的公民。

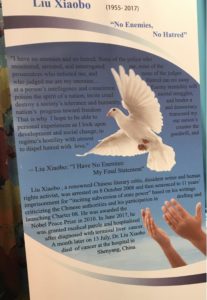

I’d like to read from his Final Statement to the judge who sentenced him: “…now I have been once again shoved into the dock by the enemy mentality of the regime. But I still want to say to this regime, which is depriving me of my freedom, that I stand by the convictions…I have no enemies and no hatred…Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience. Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress toward freedom and democracy. That is why I hope to be able to transcend my personal experiences as I look upon our nation’s development and social change, to counter the regime’s hostility with utmost goodwill and to dispel hatred with love.”

我要朗读他的《我的最后陈述》,是他写给判决他的法官的:“……现在又再次被政权的敌人意识推上了被告席,但我仍然要对这个剥夺我自由的政权说,我坚守着……信念——我没有敌人,也没有仇恨。……仇恨会腐蚀一个人的智慧和良知,敌人意识将毒化一个民族的精神,煽动起你死我活的残酷斗争,毁掉一个社会的宽容和人性,阻碍一个国家走向自由民主的进程。所以,我希望自己能够超越个人的遭遇来看待国家的发展和社会的变化,以最大的善意对待政权的敌意,以爱化解恨。”

After Liu Xiaobo’s death, a colleague who had known and worked with him for decades was asked if he thought Xiaobo would have changed his statement had he known his end. His friend said No, that his final statement and sentiment that “I have no enemies, no hatred” was at the heart of who Liu Xiaobo was.

刘晓波去世后,一位与他认识并合作了数十年的同道被问到,如果刘晓波知道自己的结局,他是否认为晓波会改变自己的陈述。他的朋友说“不会”,因为“我没有敌人,也没有仇恨”的最后陈述和观点,正是刘晓波其人的核心。

Now Liu Xiaobo’s beloved wife Liu Xia, who is herself a poet, will read one of his poems written to her: “Van Gogh and You” addressed to “Little Xia”:

现在,刘晓波的挚爱妻子,自己也是诗人的刘霞,将朗诵他写给她的一首诗:《梵高与你——给小霞》:

The Journey of Liu Xiaobo: From Dark Horse to Nobel Laureate

The Journey of Liu Xiaobo: From Dark Horse to Nobel Laureate, published April 1 by Potomac Books (The University of Nebraska Press) tracks the life and ideas of the scholar, poet and activist who has been called the Nelson Mandela of China. It has been my privilege to edit this volume, along with colleagues of Liu’s. Below is my editor’s note to introduce this book which I hope readers will embrace to celebrate Liu Xiaobo’s life and legacy. (Essay reprinted with permission of Potomac Books.)

“Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth.”—Liu Xiaobo, I Have No Enemies: My Final Statement

Available at Potomac Books, Politics and Prose, Barnes and Noble, Amazon, Powells, and Indiebound

Editor’s Note

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

A zoo in China placed a big hairy Tibetan mastiff in a cage and tried to pass if off as an African lion. But a boy and his mother heard the animal bark, not roar. As news spread, the zoo’s visitors grew angry. “The zoo is absolutely trying to cheat us. They are trying to disguise dogs as lions!” declared the mother.1

In 2009 the Chinese government put Liu Xiaobo, celebrated poet, essayist, critic, activist, and thinker into a cage, labeled him “enemy of the state,” charged him with “inciting subversion of state power,” and sentenced him to eleven years’ imprisonment. Liu Xiaobo was not an enemy, but he was a “lion” the state feared. He challenged orthodoxy and conventional thinking in literature, which he wrote and taught, and authoritarian politics, which he protested and tried to help reshape. His insistence on individual liberty in more than a thousand essays and eighteen books, his relentless pursuit of ideas, including as a drafter and organizer of Charter 08, which set out a democratic vision for China through nonviolent change, and finally his last statement, “I have no enemies and no hatred,” threatened the Chinese Communist Party and government in a way few other citizens had.

Dr. Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace, in 2010, but he was in prison, was not allowed to attend the ceremony, and died in custody in July 2017.

When news of Liu Xiaobo’s death reached the world and in particular the writers and democracy activists who knew him, writers began to write. Tributes and analyses poured in, many sent to the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), a gathering of writers inside and outside of Mainland China that Liu helped found and served as president. The Journey of Liu Xiaobo traces Liu’s history and the path of liberalism in China and is perhaps the largest gathering of Chinese democracy activists’ writing in one volume. Because of length restrictions, some tributes are listed only by authors’ names in the appendix.

A Chinese edition was published in 2017 as Collected Writings in Commemoration of Liu Xiaobo by Democratic China and the Institute for China’s Democratic Transition. It is hoped that this revised and expanded English edition, organized according to phases of Liu’s life and development, will find an even wider audience and offer insight into the person—his ideas, his loves, and his legacy. Some have suggested that because of Liu Xiaobo’s death and the economic and political ascendency of the current Chinese regime, Liu’s legacy has been reduced to a void. I would recommend that those who claim such consider the longer arc of history. The same was said of visionaries in Eastern Europe when earlier protests were crushed in Poland, East Germany, and elsewhere; the same was said of early martyrs in South Africa, where repression eventually led to widespread civic resistance and in other countries where civilians have challenged repressive systems. Liu Xiaobo was committed to nonviolent engagement and political change. Though he no longer walks the earth, his ideas and writings endure. History will unfold this story. In the meantime the essays in this volume recount one man’s journey and commitment to the struggle for the individual’s right to freedom.2

Societies move forward and are changed by ideas, by leaders, and ultimately by their citizens. None of these essays show Liu Xiaobo aspiring to personal power. But those in power worried about this man of ideas and this activist who set ideas into motion. He didn’t need to roar like a lion to garner the world’s attention and respect. By his life and his death he holds those in power to account.

Notes

———————————————————————————————————————

- Michael Bristow, “China ‘Dog-Lion’: Henan Zoo Mastiff Poses as Africa Cat,” BBC News, August 15, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-23714896..

- In these collected essays, a number of writers express concern about the fate of Liu Xiaobo’s beloved wife, poet and artist Liu Xia, who spent years under house arrest. Since the writing of these articles, Liu Xia has been allowed to go to Germany for medical treatment. As of 2019 she resides in Berlin.

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.

In those days PEN had close ties with UNESCO, and attending a PEN Congress was like visiting a mini U.N. Assembly. Delegates sat at tables with name tags of their countries in front of them. Action was taken by resolutions which were debated and discussed and then sent to the International Secretariat and back to the Centers for implementation. At the time PEN operated with three standing Committees, the largest of which was the Writers in Prison Committee focused on human rights and freedom of expression. The other two were the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and the Peace Committee. Soon, in 1991, a fourth—the Women’s Committee—would be added. At parallel and separate sessions to the business of the Assembly of Delegates, literary sessions explored the theme of the Congress.

PEN USA West was particularly active in the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) where we advocated for our “adopted/honorary” members, most prominent for us at that moment was Wei Jingsheng in China. We had drafted and brought to the Congress a resolution, noting that China had recently released numbers of individuals imprisoned during the Democracy Movement, but Wei Jingsheng had not been among them and had not been heard from. We addressed an appeal to the People’s Republic of China to give information on the condition and whereabouts of Wei Jingsheng and to release him.

Before we spoke to this resolution on the floor of the Assembly, we met with the delegate of the China Center. The origins of this center was a bit of a mystery since it was one of the few centers that defended its government’s actions rather than PEN’s principles. I still recall the delegate with thick black hair, square face, stern visage and black horn-rimmed glasses, though this last detail may be an embellishment. He argued with me that Wei Jingsheng was an electrician, not a writer, that he had simply written graffiti on a wall, but that he had committed a crime by sharing “secrets” with western press.

The Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee Thomas von Vegesack, a Swedish publisher, arranged for the celebrated Chinese poet Bei Dao, a guest of the Congress, to speak in support of the PEN USA West resolution. The delegate from Taipei PEN stood next to Bei Dao and translated his words which contradicted the China delegate. Bei Dao noted that Wei Jingsheng had been in prison ten years already, having been arrested when he was 28-years-old. He had already published his autobiography and 20 articles and for years had been editor of the magazine SEARCH. In his posting on the Democracy Wall and in his essay “The Fifth Modernization,” Wei had suggested that democracy should be added as a fifth modernization to Deng Xiaoping’s four modernizations. “This shows that Wei Jingsheng’s status as a writer can’t be questioned,” Bei Dao said. I still remember that moment of Bei Dao addressing the Assembly and his country man with a Taiwanese writer translating. For me it demonstrated PEN in action.

In Beijing at that time thousands of students and citizens were protesting in Tiananmen Square.

PEN Center USA West’s resolution passed. The China Center and Shanghai Chinese Center refused to accept the resolution. The Maastricht Congress was the last PEN Congress they attended for over twenty years.

In the months preceding the gathering in Maastricht International PEN Secretary Alexander Blokh, International President Francis King and WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack had visited Moscow where the groundwork was laid to bring Russian writers into PEN with a Center independent of the Soviet Writers Union.

Twenty-two years before, Arthur Miller, International PEN President, had also traveled to Moscow at the invitation of Soviet writers who wanted to start a PEN center.

In 1967 Miller met with the head of the Writers’ Union and recounted in his autobiography:

At last Surkov said flatly, “Soviet writers want to join PEN….”

“I couldn’t be happier,” I said. “We would welcome you in PEN.”

“We have one problem,” Surkov said, “but it can be resolved easily.”

“What is the problem?”

“The PEN Constitution…”

The PEN Constitution and the PEN Charter obliged members to commit to the principles of freedom of expression and to oppose censorship at home and abroad. Miller concluded that the principles of PEN and those of the Soviet writers were too far apart. For the next twenty years PEN instead defended and assisted dissident Soviet writers.

At the Maastricht Congress Russian writers, including Andrei Bitov and Anatoly Rybakov attended as observers in order to propose a Russian PEN Center. Rybakov (author of Children of the Arbat) told the Assembly that writers had “endured half a century of non-democratic government and had lived in a dehumanized and single-minded state.” He said, “Literature could be influential in the fight against bureaucracy and the promotion of the understanding between nations and cultures. Now Russian writers want to join PEN, the principles and ideals of which they fully shared, and the responsibilities of belonging to which they recognized…and hoped for the sympathy of the members of PEN.”

The delegates unanimously elected Russian PEN to join the Assembly. In the 1990’s and until he passed away in 2007, one of the most outspoken advocates for free expression in Russia was poet and General Secretary of Russian PEN, Alexander Tkachenko. (Working with Sascha, as he was called, will be included in future blog posts.)

Polish PEN was also reinstated at the Maastricht Congress. After seven years of “severe restrictions and false accusations by the Government which had resulted in their becoming dormant,” the Polish delegate said they were finally able to resume normal activity in full harmony with PEN’s Charter. “I must stress here that our victory we owe in great part to the firm and unbending attitude of International P.E.N. and to almost unanimous solidarity of the delegates from countries all over the world.”

At the Congress PEN USA West, American PEN, Canadian PEN and Polish PEN presented a resolution on Czechoslovakia, calling for the government to cease the recent campaign against writers and to release Vaclav Havel and all writers imprisoned. The Assembly recommended that the International PEN President and International Secretary get permission from Czech authorities to visit Vaclav Havel in prison. Two weeks after the Congress Vaclav Havel was released. In December of 1989 Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia after the collapse of the communist regime. In 1994, President Havel, along with other freed dissident writers, greeted PEN members at the 61st PEN Congress in Prague.

Also at the Maastricht Congress was an election for the new President of International PEN. Noted Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe stood as a candidate, supported by our two American Centers, Scandinavian centers, PEN Canada, English PEN and others, but Achebe was relatively new to PEN, and at the time there were only a limited number of African centers. Achebe lost by a few votes to the French writer Rene Tavernier, who passed away six months later.

Achebe admitted that he was not as familiar with PEN but said that if the organization had wanted him as President he had been persuaded that “it would be exciting.” He noted the world was very large and very complex. He hoped that in the years to come the voices of those other people would be heard more and more in PEN.

Our delegation had the pleasure of having dinner with Achebe in a castle in Maastricht which had a gourmet restaurant that served multiple courses with tiny portions. The small dinner, which also included the East German delegate and I think fellow Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta and an American PEN member, lasted over three hours. I’m told when Achebe left, he asked his cab driver if he had any bread in his house because he was still hungry. When I saw Achebe a few times in the years following, he always remembered that dinner.

At the Maastricht Congress two new Africa Centers were elected: Nigeria, represented by Achebe, and Guinea. The election of these centers signaled a growing presence of PEN in Africa. Today PEN has 27 African centers.

A few weeks after we returned from the Congress to Los Angeles, tanks entered Tiananmen Square. Hundreds of citizens, including writers, were arrested and killed. One of my first thoughts was, what will happen to Bei Dao, but fortunately he hadn’t yet returned to China. Our small PEN office started receiving faxes from London with dozens of names in Chinese, and we and PEN Centers around the globe began writing and translating those names and mounting a global protest. Among those on the lists I am sure, though I didn’t know him at the time, was Liu Xiaobo, who was instrumental in helping protect the students and in clearing the square.

Tiananmen Square. June 4th, 1989. © 1989 Stuart Franklin/MAGNUM

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Twenty years later Liu Xiaobo would be a founding member and President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He would also later help draft and circulate the document Charter 08, patterned after the Czechoslovak writers’ document Charter 77, calling for democratic change in China. In 2009 Liu Xiaobo was again arrested and imprisoned. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in prison in 2017.

The opening of the world to democracy and freedom which we glimpsed and hoped for and which seemed imminent in 1989 appears less certain now.

Today, June 3-4, 2019 memorializes the thirtieth anniversary of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square. During the years after Tiananmen when Liu Xiaobo and others were in prison I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. But that is a story to come…

Next Installment: PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East

Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo died this past July in prison, where he was serving an 11-year sentence for his role in drafting Charter ’08 calling for democratic reform in China. Below is my essay in The Memorial Collection for Dr. Liu Xiaobo, just published by the Institute for China’s Democratic Transition and Democratic China.

I never met Liu Xiaobo, but his words and life touch and inspire me. His ideas live beyond his physical body though I am among the many who wish he survived to help develop and lead democratic reform in China, a nation and people he was devoted to.

Liu’s Final Statement: I Have No Enemies delivered December 23, 2009 to the judge sentencing him stands beside important texts which inspire and help frame society as Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail did in my country. King addressed fellow clergymen and also his prosecutors, judges and the citizens of America in its struggle to realize a more perfect democracy.

I hesitate to project too much onto Liu Xiaobo, this man I never met, but as a writer and an activist through PEN on behalf of writers whose words set the powers of state against them, I can offer my own context and measurement.

Liu said June, 1989 was a turning point in his life as he returned to China to join the protests of the democracy movement. In June, 1989 I was President of PEN Center USA West. It was a tumultuous year in which the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was issued in February, and PEN, including our center, mobilized worldwide in protest.

In May, 1989 I was a delegate to the PEN Congress in Maastricht, Netherlands where PEN Center USA West presented to the Assembly of Delegates a resolution on behalf of imprisoned writers in China, including Wei Jingsheng, and called on the Chinese government to release them. The Chinese delegation, which represented the government’s perspective more than PEN’s, argued against the resolution. Poet Bei Dao, who was a guest of the Congress, stood and defended our resolution with Taipei PEN translating.

When the events of Tiananmen Square erupted a few weeks later, my first concern was whether Bei Dao was safe. It turns out he had not yet returned to China and never did. PEN Center USA West, along with PEN Centers around the world, began going through the names of Chinese writers taken into custody so we might intervene. I remember well reading through these names written in Chinese sent from PEN’s London headquarters and trying to sort them and get them translated. Liu Xiaobo, I am certain must have been among them, though I didn’t know him at the time.

In his Final Statement to the Court twenty years later, Liu told the consequence for him of being found guilty of “the crime of spreading and inciting counterrevolution” at the Tiananmen protest: “I found myself separate from my beloved lectern and no longer able to publish my writing or give public talks inside China. Merely for expressing different political views and for joining a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher lost his right to teach, a writer lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual could no longer speak openly. Whether we view this as my own fate or as the fate of a China after thirty years of ‘reform and opening,’ it is truly a sad fate.”

I finally did meet Wei Jingsheng after years of working on his case. He was released and came to the United States where we shared a meal together at the Old Ebbit Grill in Washington. I was hopeful I might someday also get to meet Liu Xiaobo, or if not meet him physically, at least get to hear more from him through his poetry and prose.

His words are now our only meeting place. His writing is robust and full of truth about the human spirit, individually and collectively as citizens form the body politic. I expect that both his poetry and the famed Charter 08, for which he was one of the primary drafters and which more than 2000 Chinese citizens endorsed, will resonate and grow in consequence.

Charter 08 set out a path to a more democratic China which I hope one day will be realized.

“The political reality, which is plain for anyone to see, is that China has many laws but no rule of law; it has a constitution but no constitutional government,” noted Charter 08. “The ruling elite continues to cling to its authoritarian power and fights off any move toward political change….

“Accordingly, and in a spirit of this duty as responsible and constructive citizens, we offer the following recommendations on national governance, citizens’ rights, and social development: a New Constitution…Separation of Powers…Legislative Democracy…an Independent Judiciary…Public Control of Public Servants…Guarantee of Human Rights…Election of Public Officials…Rural—Urban Equality…Freedom to Form Groups…Freedom to Assemble…Freedom of Expression…Freedom of Religion…Civic Education…Protection of Private Property…Financial and Tax Reform…Social Security…Protection of the Environment…a Federated Republic…Truth in Reconciliation.”

Charter 08 addresses the body politic. Liu Xiaobo’s Final Statement: I Have No Hatred addresses the individual, and for me resonates most profoundly. Its call doesn’t depend on others but on oneself for execution. He warned against hatred.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows). It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

At a recent conference a participant asked if Liu Xiaobo might have changed this statement if he understood how his life would end. A friend who knew him assured that he would not for he was committed to the idea. Liu Xiaobo’s commitment to No Enemies, No Hatred does not accede to the authoritarianism he opposed, but instead resists the negative. He aligns with benevolence and love as the power that nourishes the human spirit and ultimately allows it to flourish. Liu’s words and his ideas lived offer us all a beacon and a guide.

“Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred”

The train from Copenhagen airport to Malmö, Sweden took just half an hour across the 21st century Øresund Bridge, which spans five miles of water, then the train dove into 2.5 miles of tunnel. Looking out the window at farmland and the blue waters of the Baltic Sea, I imagined this journey was not so easy 74 years ago with Nazis in pursuit. In 1943 as the Nazis went to sweep Denmark’s 7800 Jews into concentration camps, Danish and Swedish citizens rallied, and 7220 people managed to escape in boats across this Sound to nearby Sweden. Thousands landed in Malmö where I was headed for a less dramatic, but still fraught, occasion.

Members of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) whose writers live inside and outside mainland China were joining writers from Uyghur PEN, Tibetan PEN and members from Inner Mongolia, along with writers from PEN Turkey and Azerbaijan for the First International Conference of Four-PEN Platform: “Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred.” Swedish PEN was providing the safe space for debate, discussion and strategies of action on human rights and freedom of expression. Just six weeks before, one of ICPC’s founding members and honorary President Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo, died in a Chinese prison after serving nine years of an 11-year sentence for drafting Charter 08, a document co-signed by 308 writers and intellectuals calling for a more democratic and free China.

A recognized leader in China’s Democracy Movement, Liu Xiaobo’s loss was deeply felt. A number of the writers gathered knew and worked with Liu. Most knew at least one fellow writer in prison. Many now live in exile themselves. Almost half of PEN International’s writers-in-prison cases are located in the regions represented at the conference.

The theme “No Enemies, No Hatred”—drawn from Liu Xiaobo’s final statement at his trial—sparked the debate in Malmö.

Keynote speaker Nobel Laureate Shirin Ebadi challenged, “But I do have enemies and I do feel hatred.” Facing death threats from her government in Iran, she had to leave everything behind at age 63 and move to London.

“Liu Xiaobo said he had no hatred and no enemies, but he also never compromised with any dictators,” she noted. “We must fight against dictators but our weapons are our pens and are nonviolent. We must not be silent. We can’t compromise with governments such as China who would eradicate an ‘empty chair’ from the internet.” [When Liu Xiaobo was unable to attend the Nobel ceremony because he was in prison, the Nobel Committee placed an empty chair on stage to represent him. The Chinese government is said to have censored the term “empty chair” from the internet in China.]

“What is the use of a pen if Liu Xiaobo is dead?” challenged one writer. Another speculated that if Liu Xiaobo had known how his life would end, he would have changed his message. A friend of Liu’s assured that he would not because for him no enemies and no hatred was a spiritual commitment.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows),” Liu declared to the court at his trial. “It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy…. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate…. No force can block the thirst for freedom that lies within human nature, and some day China, too, will be a nation of laws where human rights are paramount.”

Within this frame and this hope, stories of persecution were exchanged among the Tibetan, Uyghur and Mongolian writers in China and among writers from Azerbaijan and Turkey, where over 150 writers and journalists are currently in prison and over 100,000 judges, academics and civil servants have been fired.

Uyghur and Mongolian writers noted that starting September 1 the Uyghur language is banned from all schools.

“The Chinese call all Uyghurs terrorists,” said one participant. “I have never seen a gun or a bomb in my life, but my name is on Interpol’s list because of my pen. I am a German citizen, and I was in Italy, invited by the Italian Senate when Italian police arrested me because the Chinese government put me on a terrorist list because I speak out for the Uyghurs.”

Can one operate against totalitarian, oppressive governments without hatred and enemies? The question remained unresolved, but participants agreed that protest and actions needed to remain nonviolent. To amplify the voices of the writers who were in prison, those outside could publish them, protest to their governments and recognize the writers with awards. Implicit was a belief in the power of culture and ideas to ultimately change society.

The 2016 Liu Xiaobo Courage to Write Award was given at the conference to Hu Shigen and Mahvash Sabet. Writer and lecturer Hu Shigen spent his career in the Democracy Movement since 1989 Tiananmen Square when he was arrested for “counterrevolutionary propaganda” and sentenced to 20 years in prison and after release was arrested again for “subverting state power” and returned for seven and a half years in prison where he still resides. Mahvash Sabet, a teacher and noted Baha’i poet, was detained for her faith and for “acting against the security of the country and corruption on earth” in Iran and is now serving a 20-year sentence in Evin prison in Tehran. Her friend Shirin Ebadi accepted the award on her behalf.

Other cases highlighted by the conference included Ilham Tohti, Nurmuhemmet Yasin, Gulmire Imin, Memetjan Abdulla, Gheyret Niyaz, Zhao Haitong, Omerjan Hasan, Qin Yongmin, Zhang Haitao, and Mehman Aliyev. The gathering also highlighted the situation of Liu Xia, Liu Xiaobo’s wife, who is believed still under house arrest. Many are working in the hope of getting her out of China.

When Shirin Ebadi was presented a statue of Liu Xiaobo, she noted that it would sit beside a statue she’d been given of Martin Luther King.

Dr. King’s writing of 54 years ago in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” read at the closing demonstrated the power of ideas and words to endure long after their author has passed away: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Storm Cloud on a Summer’s Day

It is an almost perfect summer day—the sun is shining in a white cloud sky; the air is warm, not yet sweltering. Light filters through white umbrellas shading diners at the outside restaurant by the park. On this almost perfect New York day I am thinking about the rulers in China who have imprisoned for the last nine years one of the country’s courageous thinkers for ideas that will outlast him and his jailers.

Today it was announced Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo is in critical condition, on medical parole having been given a terminal diagnosis. As a principal author of Charter’08 which advocates for nonviolent democratic reform in China, Liu Xiaobo, writer, critic and activist has lived his life as a man of ideas.

As the sun shifts above me, skirting over skyscrapers, finding a gap between the umbrellas and spreading over my table, I consider the trajectory and the life of an idea as it dawns, unfolds, iterates, then flies off where it is embraced, where it empowers and takes on a life of its own. Ideas are connected to, but not owned or encumbered by, those who articulate them.

The fallacy—the fundamental fallacy—of the rulers in China and elsewhere lies here. No one can imprison ideas. No one can manage or own the imagination of another. Government leaders can physically restrain with the hope that the idea will die, but in the case of Liu Xiaobo, the ideas behind Charter ’08, which was signed by more than 2000 Chinese citizens from all walks of life, endure. These ideas calling for a freer society continue to grow wings, often quietly, but sometimes even more quickly as the physical confines grow harsh.

“Any man or institution that tries to rob me of my dignity will lose,” declared Nelson Mandela. It is an injunction worth noting.

Hard Edge Under the Snow

Washington, DC is emerging from its winter wonderland of nearly two feet of light powdery snow over the weekend. With snow crested on rooftops and banked along the streets, with sparkling lights blinking around town, circling the monuments and the White House, the city looks like a postcard for the holidays.

Over the weekend if you didn’t have to travel, the record snowfall—between 15-20 inches, the largest ever in December—was magical. We walked into a restaurant with a fire place, met with family and friends for lunch then played in the park with our family dogs—one old dog and two puppies—who jumped and romped and tumbled through the snow as if it had fallen for their pleasure, theirs and the children who were sledding down the hill.

But the snow has now begun to melt during the day and to freeze at night, leaving crusty, icy mounds. From the window it is still beautiful, but it is a pain if you are trying to park a car at the curb or walk along paths not dug out when it was fluffy. The holiday lights still blink, and the puppies still race across the white fields as if life was all that it was meant to be.

And yet as I sit here typing this December blog, trying to settle into the holiday spirit, I am acutely aware that half a world away a trial is under way at this very moment in Beijing for a Chinese writer and dissident whose “crime” was to draft, along with other Chinese citizens, a vision–Charter 08–calling for human rights, rule of law and democratic reform in China.

An important writer and literary critic, Liu Xiaobo was held for six months at a secret location, then formally arrested and transferred to a detention center in June, and finally twelve days ago indicted for “incitement to subvert state power.” He is being brought to trial today– December 23–less than two weeks after the indictment and on the eve of Christmas when many diplomats and journalists will be away. His motion to postpone so his defense could have time to read and prepare against the 20 volume indictment was denied. Liu’s wife was told she can’t observe the trial and has instead been named a prosecution witness. Across China activists and supporters of Liu’s have been warned to stay home and not participate in any activities in support of Liu. These actions have led China observers to conclude that the trial is purely political and a guilty verdict has already been determined.

Around the world freedom of expression and human rights organizations and activists are preparing for the worst—a long jail sentence for Liu. A vigil has been called at the Chinese embassy in New York. Petitions are being prepared and at the same time lobbying continues in the hope for some recourse.

At this holiday season when hope is celebrated and rebirth, anticipated, the voice of a single Chinese citizen echoes as light as snow falling on grass and as hard as the frozen earth beneath.

China at 60–Fate of Liu Xiaobo?

On its 60th Anniversary, China is Still Crushing Freedom

Congress should pass Resolution 151 to speak out on behalf of arrested dissident Liu Xiaobo.

From The Christian Science Monitor

WASHINGTON – The People’s Republic of China celebrated its 60th anniversary today with massive military parades, fireworks, and concerts throughout the country. In mid-November, President Obama will make his first presidential visit to Beijing, marking the 30th anniversary of Chinese-US relations with an agenda likely to include the environment, security, and the global economy.

In the time between these milestones, the fate of an individual Chinese citizen hangs in the balance and may well foreshadow future relations with China. Liu Xiaobo, one of China’s leading writers, intellectuals, and dissidents, is expected to come to trial and be sentenced after the anniversary celebrations and before the president’s visit.

That’s why Congress must act quickly. The proposed Resolution 151 calls for Mr. Liu’s release and urges China to “begin making strides toward true representative democracy.” The resolution notes Liu’s own words: “The most fundamental principles of democracy are that the people are sovereign, and that the people select their own government.”

Resolution 151 should be passed with dispatch before Liu’s trial and sentencing so that it might signal to Beijing how much America cares about the lack of freedom in China. Liu was arrested last December and charged this June with “inciting subversion of state power” for his role as one of the principal drafters of Charter 08, a document that set out a democratic vision for China. Charter 08 was originally signed by more than 300 leading writers, engineers, teachers, workers, farmers – even former public servants and Communist Party officials. It was subsequently signed by more than 10,000 Chinese citizens. The document was circulated widely on the Internet, though it is now blocked in China.

Patterned after Charter 77, which demanded basic civil and political rights in Czechoslovakia when it was under Soviet domination, Charter 08 calls for nonviolent democratic change in China and for a government that recognizes that freedom “is at the core of universal human values,” and human rights are inherent, “not bestowed by a state.”

In a recent visit to Capitol Hill, writers from the Independent Chinese PEN Center, where Liu is a former president, as well as American writers, urged members of Congress to accelerate the passage of Resolution 151. The Chinese writers, who were in touch with Liu up until the day he was arrested, say that they believe a resolution by the US Congress would have a beneficial effect and help mitigate the severity of the sentence, which could be as much as 15 years. However, the resolution needs to pass before his trial and sentencing; otherwise it will come too late.

There is wide bipartisan support for the resolution, but questions arise:

Can this essentially symbolic gesture actually help Liu? The emphatic answer from his Chinese colleagues is yes. Even if he’s not released, Chinese authorities, sensing pressure from China’s chief trading partner, might give a shorter sentence to one of its leading thinkers and writers.

Will this gesture complicate US policy toward China? The question instead should be: How can the US have a policy with China that ignores the imprisonment of major democratic activists?

The release of Liu Xiaobo would be an enlightened act that the Chinese government could take in the wake of its 60th anniversary, signaling to the world that it is not afraid of ideas.

Charter 08: Decade of the Citizen

Grandstands are rising around Washington, DC. The U.S. is preparing for the Inauguration of a new President whose campaign mobilized a record number of citizens and focused on themes of hope and change.

Half way around the globe in the world’s most populous country, a relatively small group of citizens are proposing radical change for their nation, change which reflects in large part the ideals upon which the United States was founded. However, the proponents of this change have been interrogated and arrested.

On December 10, the 60th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 300 leading mainland Chinese citizens—writers, economists, political scientists, retired party officials, former newspaper editors, members of the legal profession and human rights defenders–issued Charter 08. Charter 08 sets out a vision for a democratic China based on the citizen not the party, with a government founded on human rights, democracy, and rule of law. Charter 08 doesn’t offer reform of the current political system so much as an end to features like one-party rule. Since its release, more than 5000 citizens across China have added their names to Charter 08.

Before the document was even published, the Chinese authorities detained two of the leading authors Liu Xiaobo and Zhang Zuhua and have since interrogated dozens of others who signed. Most have been released though they continue to be watched. However, Liu Xiaobo, a major writer and former president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, remains in custody with no word of his whereabouts and fears that he will be charged with “serious crimes against the basic principles of the Republic.” The Chinese government has also blocked or deleted websites and blogs that carry Charter 08.

Charter 08 was inspired by a similar action during the height of the Soviet Union when writers and intellectuals in Czechoslovakia issued Charter 77 in January, 1977. Charter 77 called for protection of basic civil and political rights by the state. Among the signatories was Vaclav Havel, who was imprisoned for his involvement but went on to become the President of the Czech Republic after the Soviet Union ended.

Citizens around the globe, including Vaclav Havel, Nobel laureates, human rights defenders, writers, economists, lawyers, academics, have rallied in support of those who signed Charter 08. The European Union has expressed grave concern at the arrest of Liu Xiaobo and others. Petitions in support of Charter 08 and in protest over the detention of Liu Xiaobo are circulating around the world.

The arrest of Liu Xiaobo happened on the eve of Human Rights Day and the 60th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The year 2008 is also the 110th Anniversary of China’s Wuxu Political Reform, the 100th Anniversary of China’s first Constitution and the 10th Anniversary of China’s signing of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the soon-to-be 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown against students.

Charter ’08 is well worth reading. It sets out the political history of China in its forward, then proposes fundamental principles–freedom, human rights, equality, republicanism, democracy and constitutional law—upon which the government should be based. The document advocates specific steps–a new constitution, separation of powers, legislative democracy, independent judiciary, public control of public servants, guarantee of human rights, election of public officials, rural-urban equality, freedom to form groups, freedom to assemble, freedom of expression, freedom of religion, civic education, protection of private property, finance and tax reform, social security, protection of the environment, a federated republic, truth and reconciliation.

Charter 08 lays forth an ambitious agenda, one that would revolutionize the political climate and governing structures of China, but it advocates for change not through violence, but through citizen participation. Is this naive? Foolhardy? Or is this vision for China one that will inspire and empower its citizenry?

“We dare to put civic spirit into practice by announcing Charter 08,” declare the signatories. “We hope that our fellow citizens who feel a similar sense of crisis, responsibility, and mission, whether they are inside the government or not, and regardless of their social status, will set aside small differences to embrace the broad goals of this citizens’ movement. Together we can work for major changes in Chinese society and for the rapid establishment of a free and constitutional country.”

As citizens in the U.S. prepare to inaugurate a new President, the first African American President, the country is not so much realizing change as realizing in its electoral process the ideals set forth over 200 years ago.

Ideas may be repressed for a time and their authors may be persecuted, but ideas and words matter. Eventually they are the fuel for the engine of change. Those who have the courage to set them down and publish them may turn out to be the founding fathers on whose shoulders generations will stand.