Posts Tagged ‘Meredith Tax’

PEN Journey 11: Death and Its Threat: the Ultimate Censor

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

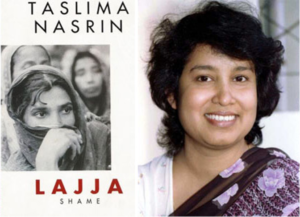

In Bangladesh novelist Taslima Nasrin was in hiding. Death threats had been issued, a price put on her life. On the streets of Dhaka and other cities, crowds threatened to hang her because of her words in a newspaper challenging the Koran and Islamic laws and because of her novel Lajja (Shame) which depicted Muslim atrocities on Hindus after a mosque’s destruction in Ayodhya, India.

The time was summer, 1994. In London Sara Whyatt, PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee Coordinator, and I sat in a Kensington hotel restaurant waiting to meet a man who’d called the office and said he was Taslima’s brother and wanted to talk with us. PEN had been actively working on Taslima’s case for the past year, sending out Rapid Action Alerts, meeting with Bangladeshi government officials in London and in the U.S. and Europe, calling on the government to protect her. The case had gained international attention. Given recent violence around fatwas, including those on Salman Rushdie, we were wary. We didn’t know Taslima had a brother. We spoke with MI5 who advised us to have a spotter for the meeting. We arranged a tell so that if the encounter was not legitimate or we perceived trouble, I would take my sunglasses from the top of my head and set them on the table. The spotter—PEN’s bookkeeper—sat at another table and could quickly summon help. We weren’t certain, but we thought MI5 was also in the hotel.

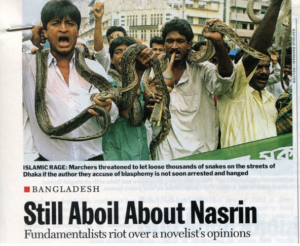

In retrospect the drama around Taslima’s case seems inflated, but during that period of 1993-1994 the situation had escalated to the point that religious leaders were warning that the government would be overthrown if Nasrin was not arrested. In June, 1994 when an arrest warrant was issued, Taslima went into hiding. A nationwide hunt was launched, and snake charmers carrying poisonous snakes marched in Dhaka and warned that thousands of snakes would be let loose if Nasrin was not arrested by June 30.

Time, July 11, 1994. Photo by Rafique Rahman-Reuters

In this atmosphere PEN had received the call from Taslima’s older brother. International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and PEN’s Women’s Committee, in particular its chair Meredith Tax in New York, had been in touch with Taslima and her lawyers, but in the time of faxes, (now fading), inconsistent telephone connections, and no internet between writers, no one had yet confirmed a brother coming through London. This kind of high drama was not PEN’s usual modus operandi. In the years I chaired PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), more than 900 writers threatened, detained, in prison, and killed came across PEN’s desk annually. Approximately a quarter of these were designated main cases which meant PEN had sufficient information to verify the situations and had members to work on the writer’s behalf. However, only a few became global causes like Taslima’s, gathering energy, attention and advocates around the world. This usually happened when the threat of death was credible and immanent and when the circumstances of the writer connected to larger issues.

That day in London, a man in his thirties approached our table. He looked so much like pictures of Taslima that we quickly set aside our suspicions. He worked for an airline and was passing through London. He was able to answer questions and confirm details of the case such as what Taslima had actually said to the newspaper which had misquoted her calling for revision of the Koran. I still have my notes from that meeting. Her brother explained that Taslima had said she wanted to modify Sharia laws, not the Koran. “I want men and women to be equal,” she’d said. She was charged with blasphemy under a law left on the books by the British.

Her brother told us that her lawyer was afraid. The lawyer couldn’t move for bail unless Taslima was present, but if the government didn’t give security for her, they couldn’t take the risk of Taslima coming to court. The government said if Nasrin went to court, anything could happen in court or in jail. In jail she could be killed. Her father’s home had been attacked, and he was now under protection.

Her brother confirmed that Taslima had finally agreed that she needed to leave Bangladesh though she was reluctant. “If I go from Bangladesh, who can write about these poor women?” she asked. And yet she wasn’t able to write anything now, he said, and her life was not safe if she stayed.

Her trial date had been set for Aug. 4. If she didn’t appear, the government would seize her things, including her passport, which they had taken away before but had returned when she resigned her post as a doctor. She was a medical doctor as well as writer.

Her brother’s message to us that day was: “Save my sister!”

Through discussions with her lawyer, with selected PEN members and with the Bangladeshi courts, it was finally arranged that Taslima would turn herself in late in the evening. Bail would be set and met, and in disguise she would leave the court. The president of Swedish PEN flew to Dhaka and accompanied her in a flight to Sweden, where she lived for years in exile.

It was lonely in exile. I met with Taslima in early September 1994, a few weeks after her arrival in Stockholm. I have notes from those meetings. “One day I’ll go back,” she said, “but I don’t know if I could live in my country anymore. I don’t know what will happen. I want to live in Bengal, but they will kill me. I couldn’t take my writing out.”

She explained that she was from a Muslim family with Hindus as her neighbors. “From the beginning I went to their houses, played with them. I know their culture, attitudes. I know their happiness and sorrow from childhood. It is not difficult for me to reach them.” After the violent incidents in Ayodhya, India where Hindu women were raped and their homes looted, she said, “I felt them. I have felt the danger and had to write for them…Why can’t I write a book in reverse, but they feel they should write my book in the case like Lajja…In India, Hindus can’t feel Muslim, and Muslims can’t feel Hindu…In Bengal, Hindu and Muslim live separately…People think men are superior to women. Women always get advice from men. Mothers are always kept quiet. It is not allowed for a mother to give advice to a son.”

London Review of Books, September 8, 1994

At the time and in retrospect at PEN we questioned whether any of our actions escalated the situation for Taslima’s case. This was the Bangladeshi government’s argument, but Amnesty and numerous human rights and freedom of expression organizations also highlighted her situation. Through IFEX, the International Freedom of Expression Exchange of which PEN was a founding member, reports circulated worldwide. The fact was, Taslima Nasrin was in real danger. PEN went into action and helped with her extraction.

In November 1994 Taslima was a special guest at the 61st PEN International Congress in Prague, opened by Vaclav Havel as the keynote speaker. In December that year she received the prestigious Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, given by the European Parliament.

Though Taslima’s case was the most celebrated at the time, there were numbers of other writers and women under threat because of their writing. In a town in Northern Greece Anastasia Karakasidou had received anonymous letters threatening to rape and kill her in front of her children because of her scholarly dissertation on the ethnic Slav population in that region. In Algeria another woman writer stayed in her house afraid even to go out on the street because her words challenged both government and fundamentalists’ violent policies. She had not received a direct death threat, but she was a well-known and recognized writer in a country where more writers had been killed in that past year than in almost any other, including Somalia, Angola and the former Yugoslavia.

Death was the ultimate censor, and the threat of death was its chilling companion. International PEN’s Writers in Prison casebook at the time listed at least 22 countries where writers were under death threats. In four countries the writers had gone into hiding. Death threats also prompted self-censorship for many writers. Most of the threats did not come directly from governments but from individuals who professed to be offended by the writer’s words. The offense, however, was almost always tied to a political or religious position, and the writer’s life became a political, not a moral, consideration.

While issues of communal violence and religious and political Islam differed from the rights of ethnic minorities in Northern Greece or from political probity in Argentina, Guatemala, Peru, Paraguay where PEN listed high numbers of death threats, the common need in all these cases was for the government to protect the writers and take action against those who issued the threats.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 12: Tolerance on the Horizon?

PEN Journey 7: PEN in Times of War and Women on the Move

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Iraq invaded Kuwait August 2, 1990. When I picked up my 10-year old son from camp in the U.S. that summer and told him what had happened, his first response was: What about Talal and Alec? These were two of his good friends at the American School in London—one was son of the Kuwaiti Ambassador; the other was from Iraq. He quickly understood the consequences. Fortunately, both of his friends had been out of their countries at the time, though I don’t recall Alec returning to the American School that fall. When the bombs dropped on Baghdad in January, the American School went into lockdown. The older students were issued identity cards. The security force around the school multiplied. When Talal came over to play that winter, he was accompanied by two imposing body guards who stayed outside.

Though the fighting in Iraq concluded by the end of February, security in London continued. By the end of March, the war in the Balkans had begun. Both wars brought to a close the honeymoon many felt after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

For PEN, the outbreak of war in Iraq and in the Balkans led to the cancellation of the planned Delphi Congress and to the convening of conferences in Europe and a two-day gathering of PEN’s Assembly of Delegates and international committees in Paris in April 1991. Delegates from 39 PEN centers came together to conduct the business of PEN at the Société des Gens de Lettres de France which occupied the 18th-century neoclassical Hôtel de Massa on rue de Faubourg-Saint-Jacques in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. There were no literary sessions or social gatherings, or the usual simultaneous translation of proceedings. The business was conducted primarily in English with intermittent French, the two official languages of PEN. (Spanish was added a few years later as PEN’s third official language.)

The Gulf War, the ethnic conflict in the Balkans, the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square trials and the ongoing fatwa against Salman Rushdie predominated discussions in Paris and later in November at the 56th PEN Congress in Vienna. The Gulf War had resulted in increased numbers of writers imprisoned and killed in the Middle East and an increase in censorship. Resolutions condemning the detention and imprisonment of writers in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Israel and Turkey passed the Paris Assembly. Little information was available from Iraq. Another resolution in Paris sponsored by the two American centers expressed concern to the U.S. government and all U.N. member states over the restrictions placed on journalists during the war and urged a review of the ground rules for journalists in conflicts.

Turkey and China continued to hold the largest number of writers in prison, as has been the case for most of my 30-year involvement with PEN. At the time the Turkish government had announced an amnesty for approximately a third of the writers, and there was some hope they might release the additional 80, but new laws were also proposed that could be used against writers. In China where 87 cases were reported, the authorities had announced the end of investigations on the leaders of the June 1989 Democracy Movement. Most sentences were lighter than expected with credit given to human rights organizations like PEN who had kept up pressure.

However, this was not the case for Wang Juntao, a 32-year old academic and Deputy Editor of the Economics Weekly newspaper. In a letter to his lawyer published at the time in The South China Morning Post Wang Juntao explained why he had spoken as he had at the trial even though he knew his penalty would be more severe. “…Only by so doing can the dead rest in peace, since on the soil where they shed blood there are still some compatriots who take risks and speak out from a sense of justice in the most difficult circumstances…” His lawyers had been given just four days to prepare his defense. He was sentenced to 13 years in prison with four years subsequent deprivation of political rights for the crime of conspiracy to subvert the government and for carrying out counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement. His lawyers pressed him not to appeal so his wife had to do so and was given only three days. The appeal was rejected. [In 1994 Wang Juntao was one of the prisoners the U.S. demanded be released as a condition for trade talks. He was released from prison for medical reasons and now lives in exile in the United States where he has studied and received advanced degrees from Harvard University and a PhD from Columbia University. PEN was among the organizations which lobbied for this release.]

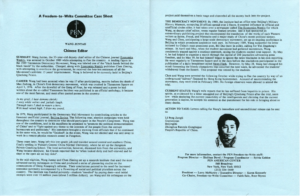

PEN International’s case sheet for Wang Juntao sent by fax and mail in 1990 to centers and members. In 1991 PEN International launched a Rapid Action Network to notify centers and to summarize the cases, actions and advocacy.

During this period PEN through its partnership with UNESCO convened writers in the Middle East and also writers in the Balkans to find common ground and to search out the pylons upon which bridges might be built and to monitor the situation for the writers in the regions. However, because of the Balkan War, it wasn’t possible to hold the meeting with the Yugoslav Centers in Bled as the Slovene Center had proposed. Instead PEN International President György Konrád hosted the gathering in Budapest and followed up with a meeting of South-Eastern European centers in Ohrid, hosted by Macedonian PEN though the Croatian Center wasn’t able to attend. The discussion included the desirability of recognizing the right of conscious objection in time of civil war and the possibility of solving the problem of minorities by allowing multiple citizenship.

Summary statement of the August, 1991 Conference on the Balkans with all centers from the former Yugoslavia attending except the Bosnian Center, which didn’t come into being until the following year.

In addition to convening dialogues among writers and lobbying on behalf of threatened writers during the Balkan conflicts, PEN also provided financial assistance. Boris Novak, the Slovene Chair of PEN’s Peace Committee and President of Slovene PEN took many precarious trips into war-torn Sarajevo during the almost four-year siege of the city. At one point he reported at least 52 writers and their families were trapped and could only leave if invited to an international peace conference. Slovene PEN planned to host such a conference and invite the writers and their families with the hope the U.N. Peacekeeping Force could provide protection for their exit. He urged other PEN centers to assist in finding residences and perhaps temporary teaching appointments or fellowships for these writers. He also delivered aid to trapped writers, aid gathered from other PEN Centers, donated to the Writers in Prison Committee Aid Fund and to PEN’s Emergency Fund run out of Amsterdam with Dutch PEN.

In an intersection of conflicts, the German and Finnish publishers of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses donated their proceeds from the book to PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. By the Vienna Congress, Rushdie had lived 1000 days under death threat. PEN continued its defense of Rushdie and its protest against the accompanying violence of the fatwa. The Japanese translator of Satanic Verses had been killed, and the Italian translator badly beaten. (Two years later the Norwegian publisher was shot three times and left for dead.) The bounty had increased on Rushdie, and there was allegedly a hit squad deployed in Western Europe to assassinate him.

One of many letters sent by International PEN to support Salman Rushdie and to protest the ongoing fatwa.

My personal engagement and memories during this period focused on work with the Writers in Prison Committee and to a lesser extent with the formation of the Women’s Committee, which I supported but which others were driving, and with the establishment of the International PEN Foundation which would be able to receive tax exempt funds for many of these PEN activities. After a discussion of the Foundation’s framework at the Paris Conference, including assurances that the Foundation would not interfere or challenge PEN’s governance, I presented the formal proposal at the Vienna Congress where the Assembly of Delegates approved the establishment of an International PEN Foundation. The Foundation received official charitable status in March 1992 and operated for the next decade until British charitable tax laws changed and a separate foundation was no longer necessary.

Also at the Vienna Congress the Women’s Network, which had formed at the Canadian Congress in 1989, gained approval as a standing committee of International PEN with assurances that men and women were welcome and would work together. Meredith Tax, a chief strategist and one of the founders, explained the committee would involve more women in the work of PEN at all levels and address problems that particularly affected women writers in developing countries and would enable women to know each other’s work, much of which was not translated. “The Women’s Committee will be a force to strengthen, not weaken PEN,” she assured the Assembly.

The eventual governance of the Women’s Committee included PEN members from around the world and its chair rotated to different regions. Each of PEN’s standing committees had its own governing structure. The Women’s Committee was unique in its inclusiveness, which had its own challenges, but which foreshadowed a more inclusive governing structure for PEN International. Twenty-eight PEN centers signed up for the committee with 70 delegates and members, including men, attending the initial meeting.

L to R: Moniika van Paemel, (Belgium Dutch-speaking PEN) and Meredith Tax (American PEN) at Women’s Committee Planning meeting at Canadian Congress, 1989

At the time International PEN’s leadership was all male. In its 80-year history International PEN had never had a woman President and only one woman International Secretary and few women as Committee chairs though in many centers of PEN there was a growing balance of men and women members and leaders. In 2015 novelist and poet Jennifer Clement was elected the first woman President of International PEN.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 8: Thresholds of Change…Passing the Torch

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.

In those days PEN had close ties with UNESCO, and attending a PEN Congress was like visiting a mini U.N. Assembly. Delegates sat at tables with name tags of their countries in front of them. Action was taken by resolutions which were debated and discussed and then sent to the International Secretariat and back to the Centers for implementation. At the time PEN operated with three standing Committees, the largest of which was the Writers in Prison Committee focused on human rights and freedom of expression. The other two were the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and the Peace Committee. Soon, in 1991, a fourth—the Women’s Committee—would be added. At parallel and separate sessions to the business of the Assembly of Delegates, literary sessions explored the theme of the Congress.

PEN USA West was particularly active in the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) where we advocated for our “adopted/honorary” members, most prominent for us at that moment was Wei Jingsheng in China. We had drafted and brought to the Congress a resolution, noting that China had recently released numbers of individuals imprisoned during the Democracy Movement, but Wei Jingsheng had not been among them and had not been heard from. We addressed an appeal to the People’s Republic of China to give information on the condition and whereabouts of Wei Jingsheng and to release him.

Before we spoke to this resolution on the floor of the Assembly, we met with the delegate of the China Center. The origins of this center was a bit of a mystery since it was one of the few centers that defended its government’s actions rather than PEN’s principles. I still recall the delegate with thick black hair, square face, stern visage and black horn-rimmed glasses, though this last detail may be an embellishment. He argued with me that Wei Jingsheng was an electrician, not a writer, that he had simply written graffiti on a wall, but that he had committed a crime by sharing “secrets” with western press.

The Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee Thomas von Vegesack, a Swedish publisher, arranged for the celebrated Chinese poet Bei Dao, a guest of the Congress, to speak in support of the PEN USA West resolution. The delegate from Taipei PEN stood next to Bei Dao and translated his words which contradicted the China delegate. Bei Dao noted that Wei Jingsheng had been in prison ten years already, having been arrested when he was 28-years-old. He had already published his autobiography and 20 articles and for years had been editor of the magazine SEARCH. In his posting on the Democracy Wall and in his essay “The Fifth Modernization,” Wei had suggested that democracy should be added as a fifth modernization to Deng Xiaoping’s four modernizations. “This shows that Wei Jingsheng’s status as a writer can’t be questioned,” Bei Dao said. I still remember that moment of Bei Dao addressing the Assembly and his country man with a Taiwanese writer translating. For me it demonstrated PEN in action.

In Beijing at that time thousands of students and citizens were protesting in Tiananmen Square.

PEN Center USA West’s resolution passed. The China Center and Shanghai Chinese Center refused to accept the resolution. The Maastricht Congress was the last PEN Congress they attended for over twenty years.

In the months preceding the gathering in Maastricht International PEN Secretary Alexander Blokh, International President Francis King and WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack had visited Moscow where the groundwork was laid to bring Russian writers into PEN with a Center independent of the Soviet Writers Union.

Twenty-two years before, Arthur Miller, International PEN President, had also traveled to Moscow at the invitation of Soviet writers who wanted to start a PEN center.

In 1967 Miller met with the head of the Writers’ Union and recounted in his autobiography:

At last Surkov said flatly, “Soviet writers want to join PEN….”

“I couldn’t be happier,” I said. “We would welcome you in PEN.”

“We have one problem,” Surkov said, “but it can be resolved easily.”

“What is the problem?”

“The PEN Constitution…”

The PEN Constitution and the PEN Charter obliged members to commit to the principles of freedom of expression and to oppose censorship at home and abroad. Miller concluded that the principles of PEN and those of the Soviet writers were too far apart. For the next twenty years PEN instead defended and assisted dissident Soviet writers.

At the Maastricht Congress Russian writers, including Andrei Bitov and Anatoly Rybakov attended as observers in order to propose a Russian PEN Center. Rybakov (author of Children of the Arbat) told the Assembly that writers had “endured half a century of non-democratic government and had lived in a dehumanized and single-minded state.” He said, “Literature could be influential in the fight against bureaucracy and the promotion of the understanding between nations and cultures. Now Russian writers want to join PEN, the principles and ideals of which they fully shared, and the responsibilities of belonging to which they recognized…and hoped for the sympathy of the members of PEN.”

The delegates unanimously elected Russian PEN to join the Assembly. In the 1990’s and until he passed away in 2007, one of the most outspoken advocates for free expression in Russia was poet and General Secretary of Russian PEN, Alexander Tkachenko. (Working with Sascha, as he was called, will be included in future blog posts.)

Polish PEN was also reinstated at the Maastricht Congress. After seven years of “severe restrictions and false accusations by the Government which had resulted in their becoming dormant,” the Polish delegate said they were finally able to resume normal activity in full harmony with PEN’s Charter. “I must stress here that our victory we owe in great part to the firm and unbending attitude of International P.E.N. and to almost unanimous solidarity of the delegates from countries all over the world.”

At the Congress PEN USA West, American PEN, Canadian PEN and Polish PEN presented a resolution on Czechoslovakia, calling for the government to cease the recent campaign against writers and to release Vaclav Havel and all writers imprisoned. The Assembly recommended that the International PEN President and International Secretary get permission from Czech authorities to visit Vaclav Havel in prison. Two weeks after the Congress Vaclav Havel was released. In December of 1989 Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia after the collapse of the communist regime. In 1994, President Havel, along with other freed dissident writers, greeted PEN members at the 61st PEN Congress in Prague.

Also at the Maastricht Congress was an election for the new President of International PEN. Noted Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe stood as a candidate, supported by our two American Centers, Scandinavian centers, PEN Canada, English PEN and others, but Achebe was relatively new to PEN, and at the time there were only a limited number of African centers. Achebe lost by a few votes to the French writer Rene Tavernier, who passed away six months later.

Achebe admitted that he was not as familiar with PEN but said that if the organization had wanted him as President he had been persuaded that “it would be exciting.” He noted the world was very large and very complex. He hoped that in the years to come the voices of those other people would be heard more and more in PEN.

Our delegation had the pleasure of having dinner with Achebe in a castle in Maastricht which had a gourmet restaurant that served multiple courses with tiny portions. The small dinner, which also included the East German delegate and I think fellow Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta and an American PEN member, lasted over three hours. I’m told when Achebe left, he asked his cab driver if he had any bread in his house because he was still hungry. When I saw Achebe a few times in the years following, he always remembered that dinner.

At the Maastricht Congress two new Africa Centers were elected: Nigeria, represented by Achebe, and Guinea. The election of these centers signaled a growing presence of PEN in Africa. Today PEN has 27 African centers.

A few weeks after we returned from the Congress to Los Angeles, tanks entered Tiananmen Square. Hundreds of citizens, including writers, were arrested and killed. One of my first thoughts was, what will happen to Bei Dao, but fortunately he hadn’t yet returned to China. Our small PEN office started receiving faxes from London with dozens of names in Chinese, and we and PEN Centers around the globe began writing and translating those names and mounting a global protest. Among those on the lists I am sure, though I didn’t know him at the time, was Liu Xiaobo, who was instrumental in helping protect the students and in clearing the square.

Tiananmen Square. June 4th, 1989. © 1989 Stuart Franklin/MAGNUM

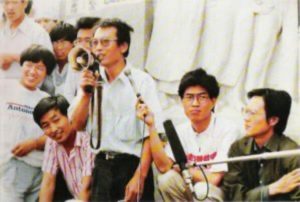

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Twenty years later Liu Xiaobo would be a founding member and President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He would also later help draft and circulate the document Charter 08, patterned after the Czechoslovak writers’ document Charter 77, calling for democratic change in China. In 2009 Liu Xiaobo was again arrested and imprisoned. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in prison in 2017.

The opening of the world to democracy and freedom which we glimpsed and hoped for and which seemed imminent in 1989 appears less certain now.

Today, June 3-4, 2019 memorializes the thirtieth anniversary of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square. During the years after Tiananmen when Liu Xiaobo and others were in prison I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. But that is a story to come…

Next Installment: PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East