Posts Tagged ‘Alexander Blokh’

PEN Journey 32: London Headquarters: Coming to Grips

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN is a work in progress. It has always been a work in progress during its 100 years. Governing an organization with centers and members spread across the globe in over 100 countries can be like changing clothes, writing a novel and balancing a complex checkbook all while hang gliding. Perhaps an exaggeration, but not by much.

In 2004 the leadership of President and International Secretary were at the center of the governing structure along with the Treasurer and a relatively new Board. The President represented PEN in international forums. The International Secretary was tasked with overseeing the office and the centers of PEN and with any tasks the President handed over like running board meetings and setting up the agenda for work. The concept was that PEN should be able to elect as President a writer of international stature to represent PEN in global forums but not have the obligation to run the organization. That could be the role of the International Secretary, along with the Board and staff.

When I assumed the role of International Secretary, PEN did not yet have an executive director, though the consensus had built from the strategic planning process that we needed one. Both the President and International Secretary were volunteer, unpaid positions, which meant they were not full time. At the post-Congress board meeting after Tromsø, we agreed to begin a search for an executive director.

I suggested monthly board meetings, which had not been the practice. We could do these by phone, which meant there were only a few hours a day when everyone would be awake. If Judith Rodriguez in Melbourne, Australia could stay up past 11pm and Eric Lax in Los Angeles didn’t mind waking up at 7am, the rest of us—Takeaki Hori in Japan, Sibila Petlevski in Croatia, Eugene Schoulgin in Norway, Elisabeth Nordgren in Finland, Cecilia Balcazar in Colombia as well as President Jiří Gruša when he joined from Vienna or Prague and me in Washington, DC or London—could find our time zone and call in. The technology was not as sophisticated as today, and we didn’t yet use skype so the calls were not cheap, but we began to manage each month.

International PEN President Jiří Gruša

As International Secretary, I was in charge of overseeing the office and staff, working with centers on conferences and projects and along with Jiří, liaising with our partners like UNESCO. Administrative Director Jane Spender and I drew up the agenda for each board meeting. I always checked with Jiří to see if he had items to add and to see if he wanted to join the board meeting. I chaired most of the board meetings and much of the Assembly of Delegates at the Congresses. English was not Jiří’s first or second language, and he had other large obligations. During his presidency, he took on the Directorship of the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna, where we held our winter board meetings. This division of tasks between Jiří and me was quite different when the next President John Ralston Saul took on the presidency in 2009, along with Takeaki Hori as International Secretary. John was a much more hands-on President than Jiří. The President and International Secretary were a team and usually agreed between them who would do what.

One of my most important and enjoyable partnerships was with Administrative Director Jane Spender, who was promoted to Program Director for Jane had been instrumental in the thinking and execution of PEN International programs first years. I tried to spend at least a week to 10 days each month in London or on the road for PEN. I was able to finance my travel outside of PEN’s budget. Jane and I worked closely together as we outlined what yet needed to be done in PEN’s move to modernize systems. Each International Secretary had operated in a way that worked for the time. In my tribute to retiring international Secretary Terry Carlbom, I’d noted that early in PEN’s life, around 1924 at a meeting in Vienna, the French representative had turned to the German representative and said, “PEN means Paix Entre Nous (“Peace between us.”).* Members did not always agree with each other and would perhaps even get angry, but the hope was that members would honor and serve that acronym well.

L to R: International PEN Program Director Jane Spender and PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman at the wall surrounding Diyarbakir, Turkey in March, 2005.

After Terry debriefed me at the PEN Congress in Tromsø, one of my first visits was to Paris to talk with former International Secretary Alexander Blokh, who had held the position for 17 years, to listen to his experience. The times and the demands were changing from Alex’s day as PEN grew and as the world sped up and shrank at the same time with the advent of the internet.

One of my early calls was to George Gawlinski, who had taken PEN through the strategic planning process in Bellagio in 2003 (see PEN Journey 28). George’s advice was that we hire an interim executive director while we did a search for an executive director. He said he happened to know that one of the best in that business was available, a man named Peter Firkin. He could come in, help us get systems in place like employment policies which we didn’t have, a budget which we didn’t have and help set up the systems the office would need to appeal to a first rate executive director and also begin relieving the impossible workload Jane and the staff bore. Jane and I interviewed Peter together. After about twenty minutes (or less), we exchanged relieved glances over the table and knew we had found who we needed for that moment.

A grey-haired New Zealander with wide experience with organizations and a love for books, Peter spoke with the Board and Jiří, and PEN hired him to come in several days a week to begin helping, including assisting in the search process. My notebook of lists had already grown quite full, and now these lists Jane and I allocated among the three of us. One of the big tasks was to develop an overall budget for the organization. The Writers in Prison Committee operated with a budget, but the rest of the organization operated project by project and at the end of the year, a list of expenses and income was recorded. There was not a budget projected forward for the whole organization, rather an accounting of money spent and money received. The only way to draw up PEN’s first budget was to look at what was spent the year before and project forward. The budgeting processes also needed to be set in place. American PEN sent over its financial director to work with the London office for a week with Jane and Peter and the Treasurer Britta Junge Pedersen and bookkeeper Kathy Barazetti. It took a while, but we eventually had a comprehensive, estimated budget for the whole organization.

Another task was to revise our status with the British Charity Commission, which oversaw all charities in Britain. The work of human rights organizations had been regarded as being political in nature, therefore not permitted charitable funds. Some organizations like International PEN had set up charitable trusts—the International PEN Foundation—to raise funds for their educational work. But with a change in the law, human rights organizations were now accepted as a-political. With Peter’s help we found a law firm that could take us through the process to dissolve the International PEN Foundation so International PEN could operate as one charitable organization.

We also found new and highly respected auditors. All these were the nuts and bolts on the continued journey to improve and modernize International PEN. During Terry Carlbom’s tenure as International Secretary, we had gotten rules and regulations and procedures updated and approved and the strategic planning process underway. The tasks and lists to get International PEN operating more efficiently seemed endless, but each day Jane and I checked more items off the lists.

We hired a highly recommended search firm, which Human Rights Watch had used successfully. Jane and Sara made it clear they did not want to be considered for the position of executive director. Jane was made the Program Director and Sara remained the Director of the Writers in Prison Committee. The board set up a committee to oversee the search, to read resumes given us, help set out the tasks and interview questions for finalists and ultimately to interview final candidates. The committee included Eric Lax, Eugene Schoulgin, myself, and Peter Firkin. We consulted closely with Jane and Sara who also interviewed the finalists.

All of this work related to the systems of the organization and were interesting and enjoyable because of the colleagues I was working with even with long hours and sandwiches for dinner at the office. But the most fun was the programs and going out into the world and working with writers. My first trip was to Dakar, Senegal, where one of our oldest African Centers had committed to host the 2007 PEN Congress and was bringing together all the African centers for a conference. One of PEN’s early Vice Presidents had been poet Leopold Senghor, who was also the first President of Senegal. A sentence I wrote and memorized before going there I remember to this day: Il n’a que qelques autre pays dans le monde ou l’ecrivain est plus honore qu’au Senegal. “There are few countries in the world where the writer is more honored than in Senegal.”

In December I left for Jamaica with Canadian PEN’s executive director Isobel Harry. Writers in Jamaica, along with UNESCO’s representative there, wanted to start a PEN Center for the Caribbean.

*P.E.N. acronym stands for Poets Essayists and Novelists; along the way it expanded to Poets Essayist/Editors and Novelists

Next Installment: PEN Journey 33: Senegal and Jamaica: PEN’s Reach to Old and New Centers

PEN Journey 24: Moscow—Face Off/Face Down: Blinis and Bombs—Welcome to the 21st Century

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

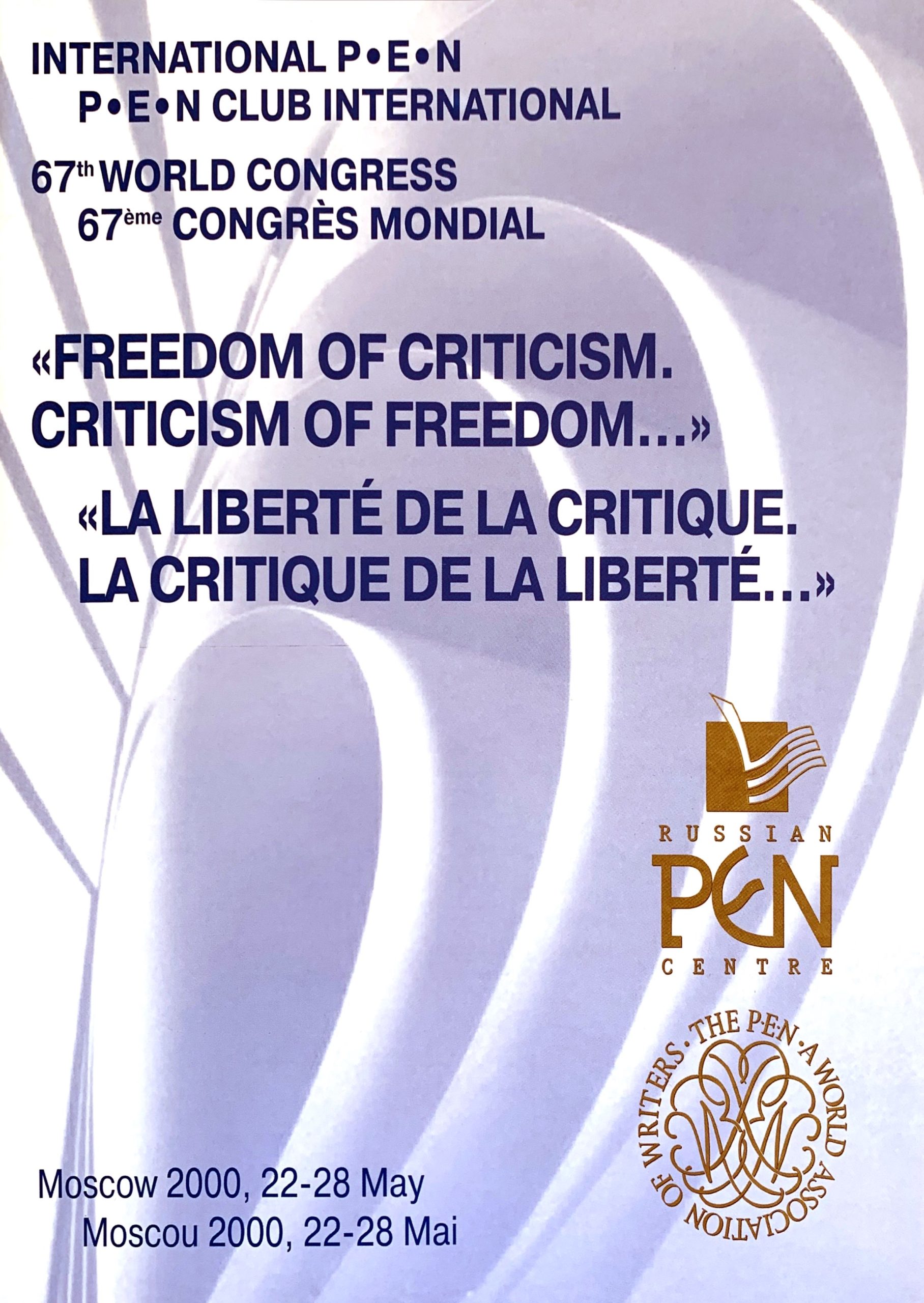

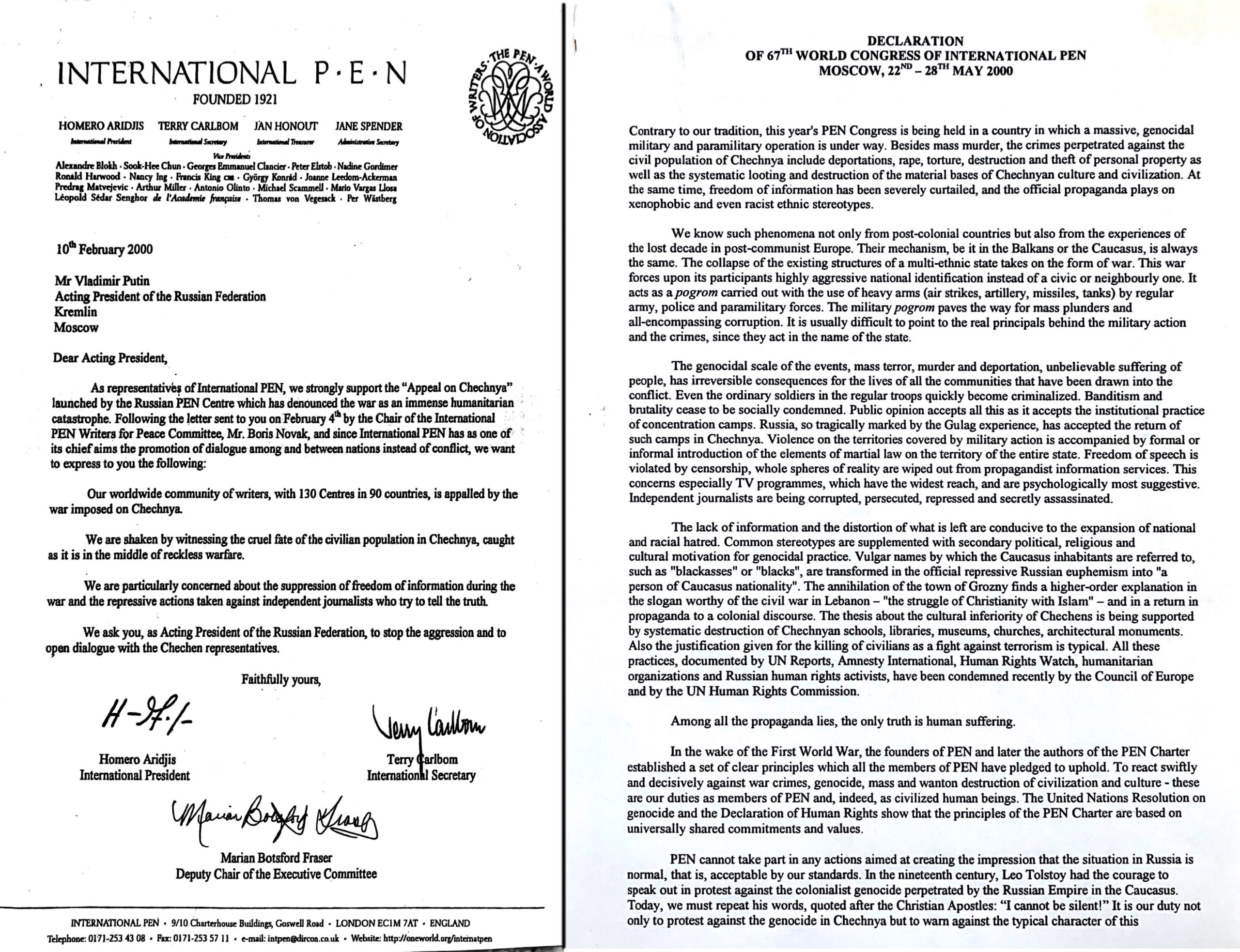

“Contrary to our tradition, this year’s PEN Congress is being held in a country in which a massive, genocidal military and paramilitary operation is under way. Besides mass murder, the crimes perpetrated against the civil population of Chechnya include deportation, rape, torture, destruction and theft of personal property as well as the systematic looting and destruction of the material bases of Chechnyan culture and civilization. At the same time, freedom of information has been severely curtailed, and the official propaganda plays on xenophobic and even racist ethnic stereotypes…” So began a Declaration from the 67th World Congress of International PEN voted by the Assembly of Delegates in May, 2000.

Program for PEN International 67th World Congress, Moscow

The decision to hold the International PEN Congress in Moscow was a controversial one, resulting in some members refusing to attend because of Russia’s prosecution of the war in Chechnya and the concern that holding a Congress in Moscow would give the government an appearance of approval. However, PEN’s Secretariat with the new Executive Committee concluded that the long-planned millennial Congress also presented the opportunity for International PEN to show solidarity with Russian PEN which had been outspoken both on the war and on behalf of Russian journalists and writers under pressure.

“The writers of Russia, united under the auspices of the Russian Centre of the International PEN Club, are concerned about the escalation of the war in Chechnya which is becoming a threat to not only peaceful residents of Grozny-city but also to the national security of Russia. The ultimatum announced to women, children and old people of the Chechen capital makes them hostages of both terrorists and federal forces. It is hard to believe that in this situation the Russian authorities are going to use the same methods as terrorists. We are very aware how hard it is to cut the tight Chechen knot, but in any case innocent people do not have to become victims of the decisions taken…” Russian PEN sent this appeal earlier to the acting President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin.

Russian PEN members, including President Andrei Bitov, had signed the appeal. Russian PEN’s General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko noted at the Congress that it was essential to call on all those involved—Russian and Chechen—to cease their brutalities. Sascha himself had regularly stood up to the Russian government. He championed the cases of imprisoned writers Alexandr Nikitin and Grigory Pasko, both of whom had recently been freed after trials. Pasko, who was a journalist and former Russian Naval officer, had been arrested and accused of espionage for his publication of environmental problems in the Sea of Japan. Nikitin, a Naval officer, had been charged with stealing state secrets by contributing to a report that revealed the sinking of Russian nuclear submarines and the dangers these decaying submarines posed to the environment.

German novelist Günter Grass talk opened PEN’s 67th Congress

The freedom and the openings which many embraced after the break-up of the Soviet Union in the early 1990’s were beginning to close down and restrictions tighten. At the Moscow Congress Pasko expressed his gratitude for everything PEN had done to obtain his freedom. He urged the Assembly to focus on environmental problems. But he warned that the structure of the current Russian government had grown out of the KGB, and he feared nothing good would come for free speech or the environment.

In the opening address of the Congress German novelist Günter Grass, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature the previous year, recounted the many times in the past century that writers had called attention to the abuses and genocides which governments had tried to hide. “At least literature does achieve this—it does not turn a blind eye; it does not forget; it does break the silence,” Grass concluded.

The Congress theme “Freedom of Criticism. Criticism of Freedom…”seemed a particularly UNESCO title, with a focus on how freedom is exercised, noting that freedom unrestrained by morality can lead to a license for corruption, brigandage, state terrorism, censorship and the wanton murder of those who dare to speak out. “That freedom is a double-edged sword is a fact long appreciated in free societies. It is what prompted Voltaire to place a limitation upon it, when it interfered with the freedom of another,” one Congress description noted.

Thus framed, the panels and the work of PEN’s committees proceeded. Many wondered how able PEN members would be to criticize openly as we met both formally and in cafes sharing conversation and meals of blinis and caviar. There was no incident nor interference that I recall at the Moscow Congress nor at the subsequent programs in St. Petersburg, but we were all aware that repercussions could follow after we left. Over time Putin’s government did close down the space for NGO’s with Russian PEN as one of the early targets. (Future blog post.)

The Moscow Congress itself proved an opportunity to celebrate Russian literature and other literature as well as to conduct the work of PEN’s committees which met in halls named after Tolstoy, Pushkin, and Chekov. Many writers from over 70 PEN centers were visiting Moscow for the first time since the Soviet Union broke apart. Since my first trip in 1991 shortly after the coup attempt (PEN Journey 8), the city had changed. Western hotels, restaurants and stores had moved in; certain citizens had amassed wealth; others had lost jobs and security. It was a city of contrasts with children on the street begging, but begging by playing violins. A wealthy new group crowded the lobbies of western hotels and department stores.

On the streets at PEN Congress in Moscow May, 2000: L: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, PEN Vice President; R: Sara Whyatt, PEN Writers in Prison Committee Program Director

In a message to the Congress Andrei Bitov wrote:

Full text of Russian PEN President Andrei Bitov’s message to PEN delegates

I always believed…that I would meet my old age in the USSR under Brezhnev, much though I disliked the idea. I could not allow myself to dream (or I would have been driven to despair) that I would be lucky enough to travel around the world more or less without restriction, that my works would be published without being censored, published with no delay and in their entirety, however hastily written.

Under Brezhnev one could not think of joining the PEN Club—that “reactionary bourgeois, anti-Soviet, etc., organization”! (It turned out only recently that Gorky, Pilniak and Voinovich had all dreamt of such a grouping…)

One could certainly never have imagined its World Congress being held in Moscow!

But fifteen years have elapsed since that time, long enough to see many people grow old and die and another generation come into the world and reach their youth. That is the History none of us, either here or in the wider world, could imagine…

We should not rail at the century that has gone, nor at the passing year—we should hope that they have taught us much. However, judging by events in Russia and in the rest of the world, it is obvious that we have not drawn any sensible conclusions from our experience…

In one tiny drop of the substance of the World Congress is reflected the entire universe, the problems it faces reflect, as in a distorting mirror, world political problems…

We are responsible for each day of our lives, not for the future.

Thank you for having the determination (and courage) to come to Russia at this particular time.

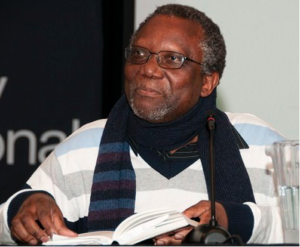

PEN’s business at the Assembly of Delegates included the International Secretary Terry Carlbom’s report on PEN’s relationship with UNESCO as the only global organization representing literature associated with UNESCO and a preliminary notice about a multi-year strategic plan under development. Business also included the election of the International President. Homero Aridjis was standing for a second term, and former International Secretary Alexander Blokh of Russian origin had returned to this PEN Congress for the first time since he’d stepped down as International Secretary in 1998, (PEN Journey 20) and he was also running for President. I was asked to chair the Assembly for the election, including during a stir that arose when Alex wasn’t present to speak for his candidature. He’d left the meeting early for an appointment, mistakenly thinking he would speak in the afternoon. However, there was no afternoon session, and controversy arose over whether the election should be postponed so he could speak. I ruled that he would be the first item on the morning agenda and then the election would proceed as scheduled. Homero Aridjis won a second term; Alexander Blokh continued to serve PEN for many years as a Vice President and President of French PEN.

Also at the Congress Martha Cerda (Guadalajara Center) succeeded Lucina Kathmann as Chair of the Women Writers’ Committee; Veno Taufer (Slovene PEN) succeeded Boris Novak, who’d opposed holding the Congress in Moscow and had stepped down as chair of the Writers for Peace Committee, and Eugene Schoulgin (Swedish PEN) was confirmed as the new Writers in Prison Committee Chair.

In his farewell comments as WiPC chair Moris Farhi quoted Günter Grass’s address that literature always breaks the silence. Moris added that by breaking the silence, by telling the truth and exposing wrong-doing, literature also defied fear and embraced courage. The members of International PEN had witnessed this defiance of fear and the manifestation of courage time and again. Moris noted among those with courage were Grigory Pasko, Alexander Tkachenko and our colleague Boris Novak.

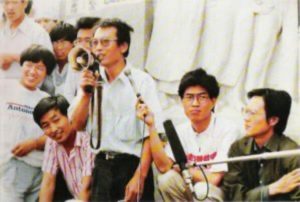

The Moscow Congress saw the return of delegates from Chinese PEN after a decade-long absence post Tiananmen Square. Two resolutions on China were presented, one calling for the release of dissident writers imprisoned in China and another protesting the long prison terms for writers in Tibet. The Chinese delegate objected to both resolutions, arguing first that Tibet shouldn’t be singled out as though it were not part of China. He also said that the Chinese people and Chinese writers cared for human rights after centuries of feudal society, but the West emphasized individual rights and values while the Chinese valued collective human rights and obligations to the family and society. The Chinese believed that human rights in a given country were related to the social system, the level of economic development and historical and cultural traditions of that country, and they encompassed the right to development and subsistence. A country of more than 1.2 billion people had to find food and clothing. It was impossible for one pattern to solve all existing problems. The Cold War had ended, but its influence remained with those who believed their values, their concept of human rights, their position were the only correct ones in the world. Dialogue was the only way to resolve the differences of view, a dialogue based on equality and mutual respect.

Hands shot up seeking to respond. At least 25 delegates at the Assembly spoke, welcoming the return of the Chinese delegates to the PEN Congress, but most taking exception to the argument of the relativity of human rights in PEN’s work. The first to speak was Eric Lax of PEN Center USA West who said he appreciated the speaker’s comments but wanted to add that the PEN Charter, to which all members subscribed, was very clear that freedom to write was a basic tenant of the organization and that information should pass unimpeded without restriction. Some questioned the way the resolution was written. Alexander Tkachenko of Russian PEN said he felt PEN should be understanding of people living under a regime about which the rest of PEN knew little. It was up to the Assembly to decide whether to support the resolution; they needn’t accept the Chinese delegate’s opinion, but they should respect it. He didn’t want the Chinese to be missing from PEN for another ten years. PEN should be tolerant of those for whom it was extremely dangerous to discuss such questions. The Assembly applauded. A small amendment was made to the resolutions, both of which passed with large majorities, though not unanimously.

The following year the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) came into being, a center of independent writers and democracy activists inside and outside of China. One of the founding members and the second president of ICPC (2003-2007) was writer Liu Xiaobo, on whose behalf PEN worked twice when he was imprisoned after Tiananmen Square and again when he was arrested in 2009. Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010, but he was incarcerated in a Chinese jail, and he died in custody in 2017.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 25: War and more War: Retreat to London

PEN Journey 21: Helsinki—PEN Reshapes Itself

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

In the old days, at least my old days, the Vice Presidents of PEN International sat in a phalanx on a stage while the Assembly of Delegates conducted business—revered writers, mostly white older men, along with the President, International Secretary and Treasurer of PEN in the center. If the Assembly business wore on, it was not unusual to see one or two of them nodding off. The role of the Vice Presidents was to provide continuity—many had been former PEN Presidents—to provide wisdom, contacts and gravitas. The designation was for life.

But times were changing. For instance, I had recently been elected a Vice President. I was a woman. I’d served PEN in several positions, including president of my center, founding board member of the International PEN Foundation and International Writers in Prison chair; I was a writer, though not of international renown, and at the time I was relatively young. I had been nominated by English PEN whose General Secretary thought it was high time more women sat on that stage. I didn’t relish sitting on a stage, but I was honored to hold the position. The Helsinki Congress in 1998 was the first when Vice President was the only role I had. I don’t recall if there was a stage at that Assembly. The fun was that I didn’t have to do anything. I could float between committee meetings, offer comments when relevant, wisdom if I had any and be called upon for whatever insight or experience or task might serve. (Traditionally the Congress organizers paid for the Vice Presidents’ registration and hotel, but from the start I chose to cover my expenses as a way of contributing to PEN. The expense of Vice Presidents attending was growing more and more difficult for the host centers; on the other hand many Vice Presidents wouldn’t be able to attend otherwise.)

Program for 65th PEN International Congress in Helsinki, Finland

At the 65th PEN Helsinki Congress held at the Marina Conference Center on the waterfront, a short walk from the city center, delegates and PEN members from 70 centers around the world gathered. The Congress’ theme was Freedom and Indifference. My memories are of meals on the water with colleagues, of eating fish and mussels and walking among old and very new buildings, visiting the architecturally stunning Contemporary Art Museum and other cultural excursions I often didn’t have time to attend when chairing the Writers in Prison Committee.

At the Congress I could even sit in on a few of the literary sessions which included abstract topics such as Where Does Indifference End and Tolerance Begin?—The Role of the Intellectual in Contemporary Society; Eurocentrism and the Global Village; The Cultural Gap Between East and West; The Ambivalence of Otherness: Identity and Difference; Crime Literature Portraying the Society; On Cultural Creolisation (mixture) and Borderlands. I confess reading those topics now stirs memories of sleepy academic afternoons, but the writers presenting included some of the engaged and engaging writers of the day, including Wole Soyinka, Caryl Phillips, Andrei Bitov and many Finnish and Scandinavian writers such as Sweden’s Agneta Pleijel.

At the Congress I still concentrated on the work of the Writers in Prison Committee which former Iranian prisoner Faraj Sarkohi attended. The year before he had been a main case for PEN, imprisoned and tortured and threatened with execution. In introducing his presence to the Assembly of Delegates, PEN President Homero Aridjis noted that PEN members could take satisfaction in having played an important role in obtaining his release. Sarkohi had managed to get a passport and was now living in Europe where he’d resumed his literary and journalistic activities.

Moris Farhi, the new WiPC Chair, introduced Sarkohi to the General Assembly of Delegates where Sarkohi said he owed his life and freedom to the international movement initiated by PEN both in the London headquarters and in the PEN centers around the world. For the first time in 20 years the Iranian government had been forced to release someone they had wanted to kill, he said. His release demonstrated to other writers in Iran that release was possible even if the government wanted to execute them. Sarkohi had briefly spoken with another PEN main case in prison who told him he was no longer worried, knowing now about the international support he was receiving.

Sarkohi explained that writers were considered by the despots in Tehran to be guilty because they worked with words, because they tried to discover and express in words different aspects of truth. It was believed writers made magic, he said. Everyone knew the magical power inherent in words so the writers were arrested. The government forced them to deny themselves, to accept false charges, and in this way they killed writers mentally. When a writer was forced by physical and mental torture to deny himself, his ideas and his work, his power of creation died, and he was killed as a writer. When Sarkohi was in solitary confinement, he remembered the way in which those suspected of magic were treated in the Middle Ages. People were arrested and burned and told “If you live, your magic powers are proved and we kill you. If you die, it is established that you do not have magic powers.’—but you were dead anyway. Writers were regarded as the new practitioners of magic in this century and that treatment by tyrants and despots was that of the Middle Ages.

Sarkohi described how he and colleagues who were still in prison had issued a new Charter, inspired by the PEN Charter, in which they protested censorship, both by the government, self-censorship and by the public such as groups which beat up a writer in the street. The Charter also demanded the right for writers to organize an association, something not permitted in Iran. He worried now about the fate of his colleagues in Iran because five years ago when writers published a Charter and sent the text abroad, the government had reacted and killed a famous translator and dumped his body in the street and murdered a famous poet in his home.

Sarkohi noted that German PEN and other PEN centers had prepared a resolution for the Congress making it clear to the Iranian government that International PEN was watching the fate of Iranian writers so they would know before they arrested or killed someone that Iranian writers were supported. He believed that support let all the world see that writers were not alone.

L to R: Mansur Rajih from Yemen, one of the first ICORN guests in subsequent years, and Iranian writer Faraj Sarkohi, former WiPC main case at PEN International’s 65th Congress in Helsinki, Finland, 1998

While the Helsinki Congress focused on the traditional work of PEN and its Committees, it was also a watershed Congress addressing the structure and governance of PEN. The Ad Hoc Committee, elected at the previous congress in Edinburgh (see PEN Journey 20), had examined the draft of revised Regulations and Rules and presented a final draft for the Assembly’s adoption. The revised Regulations and Rules were the product of two years’ work and consultations among centers. These were the first amendments to the Regulations of PEN since 1988 and the first major revision since 1979.

International PEN’s reform to provide more democratic decision-making, more communication between the International and the Centers and more transparency was not an entirely smooth transition and reflected a larger global trend at the time among the 100+ nationalities represented in PEN.

At the Congress a new International Secretary—Terry Carlbom from Swedish PEN—was elected as the only candidate, Peter Day, editor of PEN International magazine, having stepped down from consideration because of health reasons. The former International Secretary Alexandre Blokh, who had served for 16 years, didn’t attend the Congress, but was elected a Vice President and returned to subsequent Congresses.

Marian Botsford Fraser of PEN Canada, representing the Ad Hoc Committee, presented the new proposed Rules and Regulations, noting that they were “the nuts and bolts or the strings and hammers of a piano or the engine of a car or mother board of a computer. In any case their workings were unfamiliar to most writers,” she said. “It was as if we had been asked to rebuild the engine of a 1979 Audi, a vehicle renowned for the complexity of its construction. Frankly I can think of only one more difficult assignment for nine writers and that would have been to collaborate on the writing of a novel.”

She noted that the Committee of nine was a diverse collection of individuals with the wisdom that democracy sometimes magically bestowed upon its practitioners. The Edinburgh Assembly had chosen a group of people who represented the linguistic, cultural and geographic diversity of PEN and who brought to the table individually and collectively their commitment to the history and the future of PEN, their desire to remain true to the spirit of the Charter of PEN and to the identity of PEN as first and foremost an organization of writers working together to protect language, literature and the fundamental human right of freedom of expression. “We brought to the process different and strongly held views on how to make the regulations that we were charged with drafting embody those principles, how to create a structure that would become the foundation for the future of this organization,” she said.

She thanked certain Ad Hoc members, who in fact did seem to have some knowledge of the workings of a 1979 Audi and added special thanks to Administrative Director Jane Spender “who took the whole mess of scribbled bits of paper, half sentences, cryptic clauses, clearly articulated ideas and sometimes incoherent good intentions back to London, and through another process of consultation and discussion and writing and rewriting was able to turn all of this into two documents that were sent to all Centers as Draft Regulations and Rules.” Homero Aridjis, the new International PEN President, also participated in this task along with the Ad Hoc Committee.

As I read through the minutes of the Helsinki Assembly, I recalled the tensions that arose, particularly around single words such as “a-political”—after all we were an organization of writers where words and translation of words mattered—and around events that had happened off stage. Changing the way a 77-year old organization worked was perhaps more like shifting from an Audi into an SUV which could hold more people, handle more difficult terrain but also consumed more fuel and energy. But metaphors aside, after debate and discussion, agreement was ultimately achieved.

The most important change was the move to form an Executive Committee that would be the main implementing body for International PEN, a step agreed by most all Centers who chose to participate in the process. Instead of government by a small executive of the President, International Secretary and Treasurer between the Assembly of Delegates’ meetings, an Executive Committee of seven members drawn from the centers around the globe and elected for three-year terms (and up to six years) would operate along with the three executives of PEN. The election for the first Executive Committee was to take place at the 1999 Congress in Warsaw. Until then the Ad Hoc Committee would continue to function and also act as a Selection Committee to assure qualified candidates were put forward.

Details of this new structure were modified over the next twenty years. The Selection Committee evolved into an elected Search Committee to assure qualified candidates were proposed for the various offices and to gather their required papers. The Search Committee was not set up to be a guardian council or an arbiter of candidates, but a facilitator for the process. In 2005 an Executive Director was added to the equation. As with any organization, PEN keeps growing and changing, but the essential structure to broaden and democratize governance of this global organization was set in place in 1998 in Helsinki. I’m not sure what vehicle I would compare PEN to these days, probably not a finely tuned Audi, but it continues to drive.

As for Vice Presidents, that office was not changed during this watershed period of reform, but over time, PEN changed the role of Vice Presidents and designated the ex-Presidents as Presidents Emeritus instead and divided the Vice Presidents into two equal categories with twelve in each: those elected for “service to PEN” and those designated for “service to literature;” the later included internationally renowned writers and Nobel laureates such as Nadine Gordimer, Toni Morrison, Svetlana Alexievich, Orhan Pamuk, Margaret Atwood, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, J.M. Coetzee.

When I became International Secretary (2004-2007), the Executive Committee (now called the Board) and I proposed, and the Assembly agreed, that Vice Presidents’ terms should be limited, at least in the category of service to PEN—ten years or sometimes twenty—then most would move to emeritus status. It took another ten years before this change was implemented.

These are arcane details but illustrate PEN as an organization striving to keep those experienced engaged at the same time keep the organization unencumbered so it can grow and bring in new ideas and talent. It is a vehicle constantly re-tooling with the Charter as its base and a body of creative members whose greatest talents are not necessarily in rules and regulations yet who respect their necessity. Vice Presidents Emeritus, as I now am, are invited to the Congresses and show up and are still sought out for the bit of history we know and for the bits of wisdom we might offer from our experience and for continuity. We knew PEN in the days of the Audi, though even then it was perhaps not so finely tuned, I think, but it got from here to there across the globe as it still does.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 22: Warsaw—Farewell to the 20th Century

PEN Journey 18: Picasso Club and Other Transitions in Guadalajara

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN perches on a three-legged stool. One leg is literature—the work of writers around the world. The other leg is freedom of expression—the defense of writers, particularly those in authoritarian regimes. The third leg is community—the fellowship among writers from over 100 countries sharing, appreciating, translating. PEN began as a loose network of clubs after World War I and grew quickly. The governance of the organization has evolved and at times set the three legs of the stool at odd angles to each other. One such occasion was at the Guadalajara Congress in 1996 as PEN celebrated its 75th anniversary.

My file for that Congress, whose theme was “Literature and Democracy,” bulges with documents and papers and programs in duplicates and triplicates. I don’t know why it is so much larger than the other files. In retrospect, the 1996 Congress was an inflection point, a turn in the road. Maybe I was collecting evidence.

Program from PEN International 63rd Congress in Guadalajara, Mexico

At the Congress I was handing over the reins of the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), having finished my term, at least that was my intent. Ronald Harwood was doing the same as President of PEN International, at least that was his intent. Elizabeth Paterson was retiring after 28 years as Administrative Secretary of PEN, and WiPC researcher Mandy Garner was also moving on. PEN was navigating transitions, some planned, but others with a momentum of their own.

For the global context of that time, I reported as Chair of WiPC to the Congress:

“…two political phenomena have emerged, both perhaps linked to the end of the Cold War. First, we have seen conflicts erupting not so much between nations as within nations. This phenomenon, though not new, has offered particular challenges for the writer. Dozens of writers have been killed in conflicts in Algeria, Bosnia, Rwanda, Chechnya. In a number of counties with internal conflicts, including Peru, India, and Turkey, governments have used Anti-Terror Laws to arrest writers who write about the opposing parties.

“Another phenomenon is the increasing number of countries turning to the democratic process for government. The end of the Cold War saw the fall of many totalitarian regimes. Since 1990 over 50 countries have, at least on paper, turned to democracy to select their governments. However, democracy has not always settled so easily into place. One of the indispensable elements of a working democracy is freedom of expression, and this freedom has often been curtailed. Because PEN’s mandate is to protect the free flow of ideas and the freedom of writers to write, to criticize and to protest, PEN’s mission is as compelling today with newly emerging democracies as it was during the Cold War era. In country after country—from Albania, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Cote d’Ivoire, Croatia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Romania, Tajikistan, Zambia—writers can be and have been arrested on such charges as “disseminating false propaganda,” “insulting the President,” and “publishing false news.” The Writers in Prison Committee’s protests and work for these writers is fundamental in a larger political process that is unfolding…

“…Whenever one might feel despair for the way human beings can treat one another, the despair can be lifted by noting the caring of the writers who work for each other. The members of the new Ghana PEN have adopted a writer in Peru; Mexican members and Swedish members work for Turkish writers; Polish, Slovak, Nepalese, French and many other members work on behalf of imprisoned Vietnamese writers. Canadian writers are working on behalf of their Nigerian colleagues, an American writer writes in Portuguese to an Indonesian imprisoned writer; English and German writers have been in long-term correspondence with an imprisoned writer in South Korea. Danish writers are working for an imprisoned writer in Yemen; Norwegian, Finish, Austrian and Czech writers are protesting on behalf of Chinese writers; Australian and Catalan writers work for imprisoned colleagues in Myanmar/Burma…”

These corridors of concern linked men and women around the world in defense of each other and of freedom of expression. The Writers in Prison Committee was a place everyone came together to focus on PEN’s mission. Discussion on resolutions and actions began there and were taken to the full Assembly of Delegates.

That year resolutions passed and action was taken on cases in: Algeria where seven writers had been killed and many more threatened and arrested; the Dominican Republic where intolerance was growing and a writer had disappeared; Turkey where 50 writers were imprisoned and 100 others sentenced to prison; Indonesia where writers had been arrested and imprisoned and the famed writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer was under town-arrest and where in East Timor writers had been killed and leader and poet Alexandre (Xanana Gusmao) was in prison and sentenced to death; Iran where writers were disappeared, tortured and imprisoned; Central Asian Republics, particularly Tajikistan, where at least 29 journalists had been murdered in the last four years; China where dozens of writers were serving long prison sentences or were sentenced to re-education camps; Cuba where journalists were imprisoned and harassed; Mexico where journalists were killed, disappeared and threatened; Vietnam where writers were serving lengthy prison terms; and Nigeria where Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged the year before and other writers were in prison.

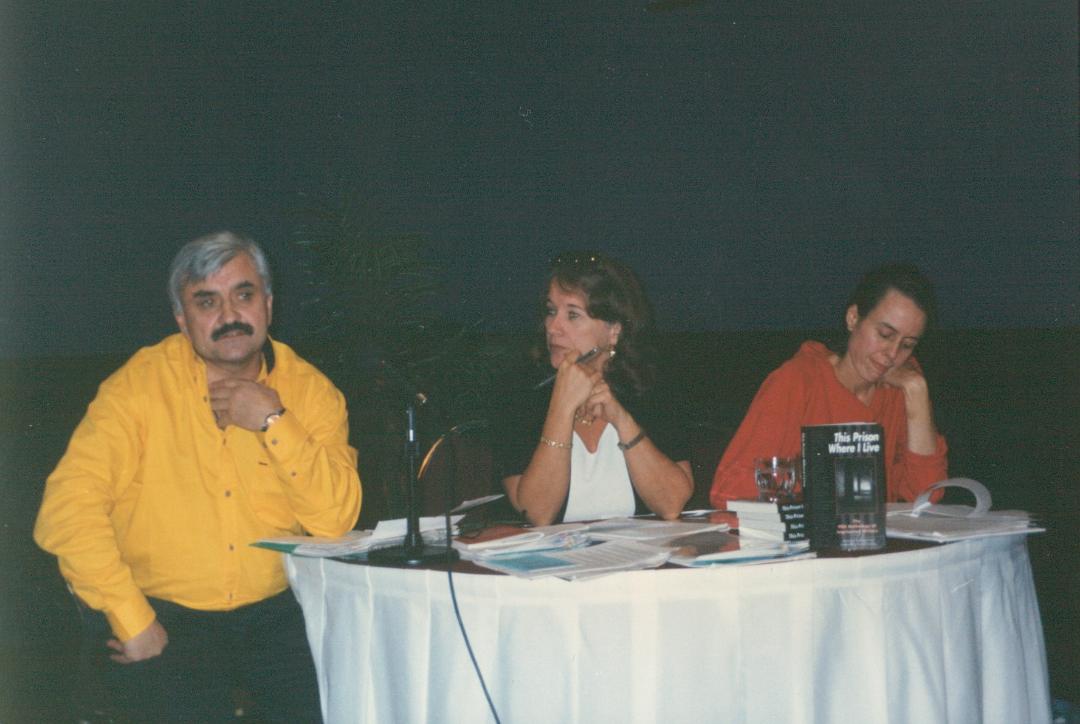

Writers in Prison Committee at Guadalajara Congress, 1996. L to R: Alexander Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (WiPC Chair), Mandy Garner (WiPC researcher)

At the WiPC meeting there was a report on PEN’s quiet mission to Cuba where writers were hoping the system would open up after the global changes in 1989. Writers there said they were in a goldfish bowl but never sure how big the bowl was from day to day, and those arrested often faced a choice between long prison sentences and exile. The WiPC meeting also heard from the sister of Myrna Mack, a Guatemalan anthropologist who had been killed and was one of the significant leaders of the worldwide movement against impunity. We also launched the anthology This Prison Where I Live of writings from PEN cases over the years.

In addition to the Writers in Prison Committee, the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, the Peace Committee and the Women’s Committee met in the early days of the Guadalajara Congress. Literary sessions focused on the Congress theme with programs on Literature of Old and New Democracies and Post-Communist Democracies.

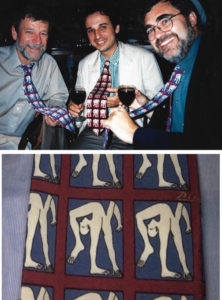

Picasso Club neckties: Top l to r: Michael Scammel (International PEN Vice President), Carles Torner (Catalan PEN), Isidor Consul (Chair PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

Also during those first days of the Congress, a group of members were meeting off site to launch a process to reshape the governance of PEN. For as long as anyone could remember, the International Secretary and President had been the sole decision-makers between Congresses where the Assembly of Delegates voted on issues. Many felt this system no longer allowed sufficient democratic expression for a worldwide organization.

I was friends with many of those meeting, but the WiPC staff and I kept out of the off-site gatherings. We felt we needed to keep the WiPC a neutral place where everyone came together. One morning the men in that group entered the Assembly of Delegates all wearing the same Picasso print necktie, “a figure twisted like a pretzel,” one member described later, ties bought at the Picasso restaurant where they had met. The group had felt shut out of discussions, and now were coming forward together. It was like a declaration of revolution. “For heaven sakes, take off the ties!” I recall someone saying, and the ties gradually were folded into pockets, but a revolution had begun.

Two Spontaneous Resolutions were introduced to the Assembly:

Spontaneous Resolution 1 On PEN’s Structure Submitted by the Swedish Centre, seconded by the Canadian Centre, and supported by the American, Bangladeshi, Catalan, Danish, Finnish, Japanese, Kenyan, Melbourne, Nepalese, Norwegian, San Miguel de Allende, Slovakian, Swiss German and USA West Centers.

Resolutions II on P.E.N’s Structure, submitted by the same centres.

“Taking into consideration the debate on P.E.N.’s composition, development and structure, held in Guadalajara on Sunday, November 10th, 1996, on the occasion of P.E.N.’s 75th anniversary;

Convinced of the need to enhance its democratic structure and facilitate wider international participation;

Resolves to request one P.E.N. Centre to elaborate the draft of a revised version of the current regulations, in cooperation and consultation with all the other Centres, as well as the International President and Secretary….”

After discussion and debate, it was agreed that PEN centers should send their suggestions for reform of the Constitution to the Japanese Centre, and Japanese PEN would coordinate and forward them to the International Headquarters and to all Centres so that the Centres could consider and vote on them at the 1997 Edinburgh Congress. One of these proposals, which was presented in Guadalajara by the Spanish-speaking Centres, was that Spanish should be made the third official language of PEN if financing could be raised.

Delegates at Writers in Prison Committee meeting PEN 63rd Congress in Guadalajara, 1996

PEN had its own democratic elections on the Congress agenda with a vote for the new International President. There was only one candidate put forward by the International Secretary and his PEN Center, a respected poet from Romania, a woman, who would have been the first woman President of PEN. She herself had lived under a repressive regime, but she had not been very involved in the international organization, and she had not been part of the discussion to reform PEN’s governance. When she spoke to the issue, questioning the need and the process, there was in the lunch conversations and in the corridors afterwards, pushback and a questioning of her suitability as President.

The next morning she withdrew her candidature. She said that it had become clear that the organization was undergoing a transformation and she felt she was the wrong person to be president at such a time of change. It seemed to her that PEN was in process of being transformed from an organization of writers into something less. She had been motivated by her dream of PEN, not as an organization with bureaucratic structures and competing pressure groups, but as a place where the writers of the world came together. She was a writer from Eastern Europe who had had great problems under successive dictatorships. From this perspective she had had an image of PEN as something extraordinary. It was true that she had confused PEN with the Writers in Prison Committee, she said. It was PEN which had spoken out when she was forbidden to publish. The work of the Writers in Prison Committee remained very important to her. What troubled her was the discovery of pressure groups who appeared to be fighting for a power which in her eyes had no existence. The only power which writers possessed was the power of their books and the fear of those in power that the truth told in those books would outlive their tyrannies.

Many members applauded her withdrawal speech. It articulated the pressure and tension in the 75-year-old organization which lived on ideals but also had to increasingly function in the competitive world of nongovernmental organizations with budgets and boards and democratic processes, an organization that needed to calibrate, modernize and keep all its members engaged.

Ronald Harwood agreed to serve another year as President. The International Secretary was reelected. Some members noted quietly that regulations required he face election every year now because of his age.

My replacement as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee was unanimously elected. The former President of Danish PEN, Niels Barfoed was a respected writer and longtime PEN member, who as a young boy had circumvented the Nazis as a courier with banned literature from his older brother who was in the Resistance. The WiPC had chosen a nominating committee to assure qualified candidate(s) were nominated. I left Guadalajara satisfied that the new WiPC process had come up with such a well-qualified Chair. I commiserated with Ronnie, thanking him for taking on another term though it meant his own writing would be curtailed. I was elected as a Vice President of PEN International and left Guadalajara happy to be returning to my own work. However, a few months later Niels fell ill and resigned, and I too was back as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee. Ronnie and I served a fourth year together.

At the end of the Congress, I went to the airport with Alexandre Blokh, the longtime International Secretary. It had been a difficult Congress for him. He questioned whether he had stayed on too long. At the Edinburgh Congress in 1997 new governance and regulations were proposed, and at the 1998 Congress in Helsinki Alex stepped down after 16 years. PEN International was on its way to having an international board and more democratic governance which presented its own challenges as the organization proceeded towards the 21st Century.

PEN International Writers in Prison Committee bimonthly newsletter, July and September, 1996

Next Installment: PEN Journey 19: Prison, Police and Courts in Turkey—Freedom of Expression Initiative

PEN Journey 6: Freedom and Beyond…War on the Horizon

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey is of some interest.

PEN members played key roles in the shifting landscape of Europe in the early 1990’s as the Berlin Wall fell, and the East moved closer to the West. Playwright and PEN member Vaclav Havel, who spent multiple stays in prison for his opposition and activism against the Communist regime, was elected President of Czechoslovakia in December, 1989. Czech writers Jiri Stransky and Jiri Grusa, both of whom spent time in jail under the Communists, later worked with Havel. Jiri Stransky became President of Czech PEN, and Jiri Grusa worked in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and later was elected President of PEN International in 2003. Dissident Hungarian writer Arpad Goncz, whose name was on the program of the 55th PEN Congress as a member of the Hungarian delegation, was prevented from coming because on the day he was to depart, he was elected President of Hungary.

Czech PEN members playwright Tom Stoppard, Jiri Grusa (President of PEN International) and Jiri Stransky (Czech PEN President) at historic restaurant in Prague in 2005

At PEN’s 55th Congress in Madeira, Portugal May,1990, Hungarian novelist Gyorgy Konrad was elected President of International PEN after the unexpected death of President Rene Tavernier. According to the interim and past President Per Wastberg, Konrad had been “very active in the spiritual liberation not only of his own country, Hungary, but of Eastern and Central Europe.”

Konrad told the Assembly of Delegates, “It had been the spirit of human rights, which corresponded with the main interest of the freedom of the mind and of literature, which had been the motive force in recent events in Eastern Europe so that it had been the spirit, rather the physical force, which had caused the shifts in power.” [But] “liberated from the uneasy situation of the censorship of the one-party system, writers there were facing a new sort of danger, the danger of conflicts between nationalities spurred on by national chauvinism. If it was possible to find understanding between writers in that very disturbed part of Europe, maybe it would also be easier to find understanding between the governments and the peoples. Therefore the PEN Centers and their members could perhaps form the avantgarde of this understanding.”

The East German delegate noted it was “the writers, theatre people and artists of the GDR who had blown that trumpet and done a great deal to bring about the collapse [of the wall.] It was they who had called for a huge demonstration on 4th November, at which two million people had gone out onto the streets of East Berlin, demanding changes.” The GDR PEN Center had also “blown the trumpet much earlier when they had supported Vaclav Havel and demanded his release from prison, which, at that time—more than a year ago—had been a thing not without danger in the GDR,” he said.

Yet the breaking up of the Communist regimes with their centralized authority was also leaving in the wake difficult conditions for many writers. Their publishers were closing, their livelihoods shrinking, and the West was taking over. “This did not mean that the writers of the GDR did not wholeheartedly go out onto the streets when they were called on to demonstrate for freedom of expression of writing, of thought and of travel,” the East German delegate said. But “now they had to take the harder road to freedom as Brecht had put it, with a proud bearing, even if they might lose in the process.”

The delegate from Poland saw two major problems ahead: “The first was political: the danger that the remnants of Stalinism might ally with the proponents of extreme right chauvinism. To overcome this danger it was necessary that the new democracies should be stabilized. The second problem was cultural: to find models for cultural life in their countries. They did have a very serious crisis in the domain of publication.”

Because of the collapse of currencies and income in these countries and the withdrawal of state support for arts and culture, it was increasingly difficult for the writers and PEN centers to pay their dues to International PEN and to find funds to travel to conferences and congresses. This situation also existed for many writers in Africa and Latin America where PEN had expanded its centers. In 1990 there were 96 PEN centers around the world.

At the Madeira Congress, PEN set up a Solidarity Fund to which countries with stronger currencies and income could contribute to assist their fellow members. The Assembly of Delegates formalized a procedure for a small, but broad-based committee to make these grant decisions. I was asked by the two American Centers to represent them on the committee, which also included representatives from Zimbabwe, Cote d’Ivoire, Polish, Soviet Russian, Canadian, English and French PEN Centers. Looking back, this new, more democratic process for dispersal of funds foreshadowed major change in PEN International’s own governing structure, change that was to come by the end of the decade.

“The collapse of the Berlin Wall…only provided an entry into the Promised Land…[but did not] overcome all the problems of coping with liberty for the first time,” reflected International Secretary Alexander Blokh to the Assembly of Delegates. “Now was the honeymoon period between East and West, but there was cause to fear that it might not last…While the trumpets of Jericho still sound in our ears, we should take steps to face up to these problems and iron out possible misunderstandings.” For this purpose PEN had held and was holding conferences in Vienna and Budapest with writers in the region.

The Congress discussion around the tectonic changes in Europe and the impact elsewhere occurred in idyllic Funchal, the capital city of Portugal’s Madeira archipelago, surrounded by hills, set on an expansive harbor with gardens and flowers everywhere. A cable car took delegates to the top of the island which offered sweeping views of the hillside neighborhoods and the town below. My specific memories are of bougainvilleas and the beauty of the setting, of the combined joy and worry of colleagues who used to emerge from the “Iron Curtain” to attend PEN gatherings, and now felt relief in their freedom but uncertainty about their lives and the future of their countries.

I remember specifically the establishment of the Solidarity Fund which operated in the 1990’s to help bridge the economic differences within PEN so that all centers could participate. PEN’s policy, though with exceptions, was that a center had to pay its dues in order to vote in the Assembly. Gilly Vincent, who later assisted the International PEN Foundation, remembers working late one winter’s night in the International PEN office when the doorbell rang. She went downstairs to find the Secretary of Polish PEN standing in the shadows at the front door. He had come to pay his Center’s dues in cash. She took the envelope and invited him in so that she could give him a receipt. He replied: “No. We carry no receipts” and vanished into the darkness, she recalls.

My memory of the Madeira Congress includes sharing meals with colleagues from Eastern Europe and with the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, author of the famed Babi Yar who attended as a delegate from the new Soviet Russian PEN Center. [At the Vienna Congress a year later in November, 1991 the Soviet Russian PEN Center got approval to change its name to Russian PEN after the August coup where the Center had issued a statement “true to the best traditions of PEN”.] Yevtushenko, dressed as I recall in rather flamboyant clothes—all white suits (or were they all red or plaid?) commanded attention wherever he went. In the Assembly he spoke in support of a new Belarusian Center which he said would symbolize the democratization of the Soviet Union. He said its members would be helpful in the common fight on behalf of persecuted writers. He spoke in support of the Kurdish Writers Abroad Center changing its name to the Kurdish Center so that Kurdish Writers in Turkey wouldn’t be accused of “separatism” for joining it. And he supported PEN holding a conference in Alexandria, Egypt, where he said PEN must do everything possible to help Salman Rushdie and must ask Arab colleagues in Alexandria for support.

Richard Bray (PEN USA West Executive Director ), Carolyn See (PEN USA West President), and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman at the 55th PEN Congress in Madeira, Portugal

At the Writers in Prison Committee meetings and at the Assembly, PEN delegates also focused on the continuing crackdown in China, on the persecution of writers, editors and publishers in Turkey, Myanmar, Vietnam, Sudan, Cuba, and El Salvador. They protested the house arrest of the renowned novelist Pramoedya Ananta Toer in Indonesia. In May, 1990 PEN recorded 381 cases of writers in prison or banned. In spite of the changes in Eastern Europe, the numbers of persecuted writers had not declined worldwide, and there were still some cases in Central and Eastern Europe. PEN resolved to act in all these areas, but the seismic shift in the political landscape of Europe held the focus for the 55th Congress whose theme for the literary sessions was Language and Literatures: Unity and Diversity.

The breakdown of the Communist states was already leading to heightened nationalism, in no place more acutely than in the Republic of Yugoslavia. While most PEN members defended the move towards freer and more tolerant societies, there were some who espoused the nationalistic sentiments that led to the war which eventually broke out in the Balkans. A few took leadership roles in that conflict and separated from PEN which had centers in the former Yugoslav republics—Serbian PEN, Croatian PEN, and Slovene PEN. Only Slovene PEN attended the Madeira Congress. Slovene PEN had long been the annual host for PEN’s Peace Committee which met in Bled, Slovenia, an idyllic town on a lake where it was difficult to imagine war.

But war was on the horizon in the Balkans. What no one anticipated was that war was also on the horizon in the Middle East for in less than three months after the Madeira Congress, Iraq invaded Kuwait. By January, 1991 America and 39 other nations were at war with Iraq. The upcoming PEN Congress in Delphi, Greece had to be cancelled; the conference in Alexandria had already been cancelled at the Madeira Congress. Two months later, in March 1991 the first shots were fired in the Balkans in a war that would last four years.

Next Installment: PEN in Times of War and Women on the Move

PEN Journey 5: PEN in London, Early 1990’s

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

I moved to London where International PEN is headquartered in January 1990 from Los Angeles. I came with my husband and my 9 and 11-year old sons who rarely wore long sleeves, let alone coats or jackets. A few weeks into our resettlement, London spun in its first major tornado of the decade with hail and winds whipping at hurricane force and cars and trees toppled and a few rooftops airborne. The weather was highly unusual for London. Our family, who was still in temporary housing, took the unwelcome weather as a welcome of sorts, signaling that we might just be in for an adventure. Did you see that roof flying…!

There were still complaints: only four television channels, movies strictly restricted by age and when you did get into a theater, you had assigned seats, milk that went bad in a day, delivered on the stoop in glass bottles, a refrigerator that barely held enough food for a day, appliances that came without plugs…And where was the sun?

Yet the magic of the city quickly affected us all. My youngest son discovered the best skateboarders lived in London, and London (and England) was full of history and castles, and my oldest son, who was soon moved ahead a grade in school because he was highly talented in math, met students from all over the world in his class at the American School, a few of whom talked and imagined in his orbit. He was put on the rugby team to help socialize and the following year on the wrestling team, where he eventually, as an adult and by then dual citizen, wrestled for Great Britain in the Olympics.

For me, finding home in London meant connecting with PEN, both International PEN and English PEN. Writers can be members of more than one PEN center, though can vote with only one center. I’d begun my PEN journey in Los Angeles at PEN Los Angeles Center (changed to PEN USA West). When my second book was published, I also joined PEN American Center, based in New York, and now in London. I joined English PEN, the oldest and the original PEN center since the organization was founded by British writers in 1921. International PEN and English PEN had separate offices, but the Administrative Secretary of International PEN and the General Secretary of English PEN were longtime friends and actually lived next door to each other in Fulham. The two organizations worked independently, yet closely together.

Early on I visited International PEN’s office, headquartered in Covent Garden on King Street in the Africa Centre. To get to the office at the front of the house, you had to go through the Africa Book Shop on the first floor. PEN had two rooms with several desks in the larger room with papers stacked everywhere. There was a filing cabinet and a photocopier and just enough space to squeeze between to get to the desk looking onto the street.

International PEN was kept functioning by the stalwart and efficient Elizabeth Paterson, who I don’t recall getting angry at anyone even as the work piled on and people around the world in PEN centers asked more and more of her, including the smart, demanding International Secretary Alexander Blokh. Alex flew in every month, usually from Paris, and displaced the Writers in Prison Committee’s small staff from the second office in order to conduct the business of PEN around the world. Alex was a former UNESCO official, and at that time UNESCO was one of International PEN’s major funders. When UNESCO was formed, according to Alex, it established organizations for the various arts, but when it came to literature, it recognized that PEN already existed, and so its outreach and funding funneled through PEN. Over the years PEN has grown more and more independent of UNESCO support.

Elizabeth, with her quiet intelligence and subtle humor, managed to keep International PEN running day to day while Alex developed the literary and cultural programs with the centers and the standing committees—the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, the Peace Committee, and the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). The WiPC tended to operate more autonomously with its elected chair Swedish publisher Thomas von Vegesack and before him Michael Scammell. When I arrived in London, there was also a petite gray-haired woman Kathleen von Simson, a volunteer who’d helped manage the Writers in Prison Committee work for years. PEN had recently hired a paid Coordinator Siobhan Dowd whose task was to professionalize the human rights work, and Siobhan hired researcher Mandy Garner. The two of them worked in the tiny second room. Siobhan eventually crossed the ocean to head up the Freedom to Write program at American PEN.

Fall 1990. Left to right: Elizabeth Paterson, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Per Wastberg (former PEN International President), Siobhan Dowd, Bill Barazetti

Also finding space on King Street was the Assistant Treasurer (and later International Treasurer) Bill Barazetti, who at that time was an unsung hero from World War II. It was later publicized that Bill had smuggled hundreds of Jewish children out of Prague with false identity papers he arranged. He was a wiry gray-haired former intelligence officer who’d also interrogated captured German pilots. Alex Blokh, whose pen name was Jean Blot, was an exiled Russian Jew, a lawyer and had also been active in the French Resistance during World War II, and Elizabeth had endured the bombings in London during the War. Though it was 1990 and the Berlin Wall and other barriers which had gone up after World War II were now falling, in the PEN office there was still a feeling of that post-War period, an abstemiousness and a fortitude of the dedicated amateur who knew what sacrifice was and endured no matter what. I couldn’t articulate the atmosphere at the time, but as an American born after the war, grown up in Texas and moving to London from Los Angeles, I felt the contrasts and the constraints. One small incident I remember was when a donation for a baby gift for the newly hired Sara Whyatt was being gathered. I offered £20 for the pot and was told by Elizabeth, “Oh, no, that amount would embarrass her.” The concept of anyone being embarrassed by a pooled £20 contribution silenced me. I put in £10 instead, still considered a large amount. Because I was new and an American, I tried to listen and learn, but I understood expectations and horizons were different.

A generation of my own joined the office in the persons of Jane Spender, a former editor, smart and literary who worked with Elizabeth and later Gilly Vincent, who took on the part time assignment to help with development work for the eventual International PEN Foundation. (see PEN Journey 4) Later Gilly became General Secretary of English PEN. I quickly learned to respect the differences; the American way was not the British way. I remember a fundraising event in which there must have been 20 major English writers featured and attending, and the ticket price was £25. The PEN Foundation netted perhaps £3000 that evening. In New York with that line up of writers, I am confident American PEN would have added at least one, if not two, zeros to the proceeds, but we were in London, and the event was not a glittery affair but more like a large family gathering of literary friends at someone’s home.

PEN International moved its offices in 1991 from Covent Garden to Charterhouse Buildings in Clerkenwell nearer the City of London. The new offices were on the top floor of a bonded warehouse, and I never met anyone who didn’t arrive breathless after climbing the steep four or five flights of stairs. There was no elevator, but there was an outside hoist where PEN could load supplies and mail out the window and drop or raise these to and from the ground, preferably not in the rain. Elizabeth set the door code as the beginning and ending years of World Wars I and II, an 8-digit code everyone could remember. The offices at Charterhouse Buildings were spacious compared to King Street—two large airy rooms, one for the Writers in Prison Committee and one for all the other work of PEN, a spacious entry room used as a meeting area and a smaller private office where the International Secretary could work or small meetings could be held. All the rooms were painted “magnolia”–a creamy white/yellow color. The full-time staff by then was, I think, three, along with four or five part-time staff and volunteers, including Jane Spender, Peter Day, editor of PEN International magazine, Bill Barazetti and later his daughter Kathy and occasional interns.

When Siobhan prepared to leave for the U.S., Thomas asked me to interview candidates with him for her replacement. Between interviews he explained to me his view of England in the constellation of Europe by a story of when a fog settled over the English Channel and the headline in a British paper announced: Continent Isolated. Later, when the Channel Tunnel finally connected Great Britain to France in 1994, I sent Thomas a note and a copy of the headline from a British paper: “You’ll be glad to know, Thomas: Continent No Longer Isolated, the headline read.

Thomas and I agreed on the best candidate, and PEN hired Sara Whyatt as the new Program Director of the Writers in Prison Committee. Sara came to PEN from Amnesty and set about further professionalizing WiPC’s research and advocacy work. Sara and Mandy split up the globe, with Mandy focusing on Latin America and Africa.

Across London in Chelsea, English PEN rented offices from the London Sketch Club on Dilke Street where it held weekly literary programs, a monthly formal dinner, an annual Writers Day Program honoring one writer—Arthur Miller, Graham Greene, and Larry McMurtry were three I recall—and a mid-Summer Party. The literary programs and dinners, held in the Sketchers studio and bar, featured writers such as Michael Ignatieff, Germaine Greer, Michael Holroyd, Jan Morris, Rachael Billington, A.L. Barker, Penelope Lively, Andrew Motion, A.S. Byatt, Margaret Foster, William Boyd, Margaret Drabble, Iris Murdoch, and frequently Antonia Fraser, Harold Pinter and Ronald Harwood, just to name a few.

When I moved to London and joined English PEN, the General Secretary Josephine Pullein-Thompson, a stalwart writer/member, managed the organization and kept it running with minimal staff and with active members. Author of young adult novels, Josephine wrote books about young girls and horses. When I close my eyes, I can hear her gruff voice and see her square face and think of horses. She was pragmatic and no-nonsense and what I think of as the epitome of a certain era of British resolve. She befriended me early, I think, because I was focused on a task—getting charitable status for PEN International which ultimately allowed English PEN to claim the same. It was Josephine years later who nominated me as a Vice President of International PEN.

Members of English PEN were passionate about PEN’s mission to protect and speak up on behalf of writers under threat in oppressive regimes. Among activities, members, including notable British writers such as Ronald Harwood, Harold Pinter, and Antonia Fraser, who were good friends, and Moris Farhi, a Turkish/British novelist with a great beard, great girth and great heart, who later succeed me as Writers in Prison Chair, and dozens of other English PEN members held vigils, often by candlelight. They protested outside embassies of countries where writers were in prison. They got press coverage and ultimately helped secure the release of writers, particularly those in former Commonwealth countries like Malawi.

Malawian poet Jack Mapanje recalled his spirit lifting when he saw the press clippings of Harold Pinter and others protesting outside the Malawi Embassy in London on his behalf. When he was released, he resettled in England and joined English PEN.

Jack Mapanje

Next Installment: Freedom and Beyond…War on the Horizon

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.