Posts Tagged ‘Eugene Schoulgin’

PEN Journey 46: Wrapping Up

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

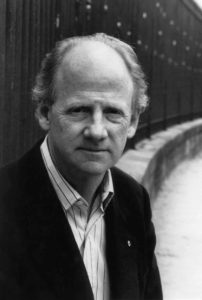

I finished my term as International Secretary of PEN July 2007 at PEN’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal. I handed over the responsibility to my longtime colleague Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) who would continue to work with the Board, the Executive Director Caroline McCormick, new Treasurer Eric Lax and President Jiří Gruša. We had executed many changes in the last three years, and those who had been involved were continuing and active both in the international leadership and in the PEN centers.

Before the Congress, the staff and PEN members gave me a farewell party at PEN International’s relatively new London headquarters on High Holborn. PEN is about people, and I’d been fortunate to work over many decades with dozens of talented writers who were also competent in organizational work, friends from around the globe who remain friends today.

PEN International Farewell gathering in London 2007 with friends and staff, including Caroline McCormick, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Jane Spender, Sara Whyatt, Moris Farhi, Peter Firkin, Eugene Schoulgin, Frank Geary, Emily Bromfield, Mitch Albert, Mandy Garner.

As a Vice President, I would continue to work, write appeal letters to governments for the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC)’s RAN (Rapid Action Network) cases, speak when asked and hold meetings in Washington when asked, but I could return to being a writer. American PEN’s Executive Director Michael Roberts asked me to join American PEN’s board. I demurred and said I needed a break, but he and others urged me so in 2008 I joined the board of PEN America but worked at a far less intense pace for the next six years. When American PEN’s new Executive Director Suzanne Nossel came on, I was asked to extend for an additional year as a Vice President while she oriented to PEN’s international work. It is difficult to step away from PEN though most who are engaged find they must for a time, though not too far away.

As I left the historic Senegal Congress that July 2007, I boarded a plane and flew out over the Atlantic to Italy where I met up with my husband by a lake in one of our favorite spots for a vacation. He had patiently waited those three years as I spent 10-15 days a month on the road. In the first week without PEN’s emails and phone calls and conferences, we talked; I wrote, and I read four books in six days.

Back home I soon realized I needed to join the 21st century as a writer. At PEN we had begun to use some tools of social media in publicizing cases of writers under threat, but I hadn’t engaged personally. I remember sitting with a group of women writers in Washington, DC, many younger than me, who were talking about their websites and blogs and Twitter, and Facebook. In 2007 writers having URLs, Twitter handles, Facebook pages was relatively new. Twitter had only launched the year before, and though blogs had been around for a few years, I had never written one. Facebook seemed an odd medium, also only a few years old. I was of the “private” generation; we were not prone to sharing our activities and feelings on a “social” platform. Those of us who’d been journalists were used to having to condense stories, but never to 140 characters which Twitter demanded. We were in a new communications age, and I needed to understand and at least to put a toe in the water, even if I didn’t jump fully in.

Encouraged by friends and agent, I set up a website. The developer urged me to blog. I didn’t want to blog, I explained. I wanted to write fiction and occasional journalism, but I agreed to post a blog once a month. I have done so for over ten years now. Often when I considered what was worth writing about each month, I found myself reflecting on work with PEN. When asked to write about PEN’s history as I’d witnessed it in anticipation of the Centennial, I reasoned I could post twice a month. That seemed a reasonable way to get through PEN’s history year by year. A serial blog. I have sped up the pace since Covid locked us all into our homes and travel has halted. I have now come to an end of this particular PEN Journey though I will write an introduction. I will also reference links to those blog posts I wrote after 2007 when I continued to work with PEN.

In this final post, I want to review a few areas of PEN International I feel I haven’t explored sufficiently, and I want to give a quick view forward of what and who came next.

In Journey’s 7, 8, 22, 25, 26, I touched on the work of the PEN Emergency Fund. I want to highlight that here. Founded in 1971 by Dutch Writer A. (Bob) den Doolaard who had an active role with PEN International, the PEN Emergency Fund fulfilled a missing link in PEN’s work. Doolaard noted that PEN had no mechanism to grant material aid to writers, especially those under threat who had to flee their countries so he and Dutch PEN set up the aid fund based in the Netherlands, operated under Dutch law. The PEN Emergency Fund gives a one-time grant to writers in dire circumstances and is able to act quickly. Over the years PEN’s Emergency Fund has provided rapid support for writers on every continent, especially those in Eastern Europe during the Communist era and those in the Balkans War in the 1990s and also to persecuted writers in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Every year dozens of writers have been helped with grants that have bridged to longer term answers. The Fund operates in close collaboration with PEN International whose professionals furnish the Fund with information and with the PEN centers and members who have contributed to the Fund. I’ve had the privilege of serving on the PEN Emergency Fund Advisory Board for a number of years.

Prizes: As a literary organization, PEN through its centers awards numbers of literary awards, but only a few literary prizes have been awarded by PEN International. Over the years the idea of a PEN International Prize for Literature or even for Peace has arisen. When I first took on the position of International Secretary, we were approached by a donor offering to give PEN $100,000 for the PEN International Prize for Peace. Well-meaning though the donor was, it quickly became clear that PEN International could not accept. The donor already had his first winner in mind—Bono. We explained that any prize would have to be independently judged with established criteria and nominating processes, and in order for PEN to give an annual prize, we would need to have a substantial financial commitment in an account to assure we could afford the prize each year as well as the cost of the judging and ceremony. We named the figure. The discussions broke off though the donor, I think, did find another way to give his prize though not through PEN.

Chimamanda Adichie, PEN David T. Wong International Short Story Prize winner.

The biennial PEN David T. Wong International Short Story Prize did come into being for a time, with a much more modest monetary award for a new writer, open to nominations by all PEN Centers and run by International PEN Foundation’s Gilly Vincent, who later became General Secretary of English PEN. Gilly was a pro and lined up well-qualified writers as judges. The nominations came in from PEN Centers around the world and the winner was often celebrated at PEN’s Congress. One of the first winners for 2002-2003 was a young Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie, who won for her short story “One Half of the Yellow Sun,” submitted by her local PEN Center USA West. The story went on to become the celebrated novel by the same name, and she went on to win wide international acclaim for that and other books. The PEN David T. Wong Prize was one of the first international recognition of her as a writer. The judges for 2003 were William Trevor, Michele Roberts and J.M. Coetzee who won the Nobel Prize for Literature later that year. The 2001 prize had been won by Rachel Seifert, who went on to have her first novel short-listed for Booker Prize.

PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, the PEN Emergency Fund and Oxfam Novib each year do give the Oxfam Novib/PEN International Free Expression Award to writers who work for freedom of expression in the face of persecution. The award is given to writers and journalists committed to free speech despite the danger to their own lives.

Turkey visit—on the roof with Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Carl Morten and Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN)

Many other literary awards and literary festivals are hosted by PEN’s centers around the world. I had the pleasure of visiting a number of those, including in Croatia and in Turkey, hosted by the PEN centers.

There are many aspects of PEN’s work I’ve touched on but not explored fully such as the formation of a PEN center, which technically can occur when 20 reputable writers get together and petition the International office. There is a limit of five centers per country; most countries have fewer, and many countries have only one center. The rationale for additional centers has been to reflect linguistic diversity in a country. For instance, Switzerland has French, German, Italian, and Esperanto centers, or to facilitate participation when the land mass is large. The U.S. used to have two centers, one based in New York and one in Los Angeles, but in the past years, the two centers have merged into one PEN America. In Canada where there is both large land mass and diverse languages PEN has two centers—PEN Canada based in Toronto essentially uses English as the primary language and Quebecois PEN uses French. In some countries there are many, many languages as in India, which also has a large landscape and has the All-India Center in Bombay and the PEN Delhi Center. The rationale depends largely on the ambition and needs of the writers on the ground. Often a center will form branches within a country to provide the services and community for writers.

One document I did not include in an earlier post was the rationale from PEN International Vice President and Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer regarding the formation and naming of centers as related to a petition from writers in South Africa to form an Afrikaans Center. I’ve copied it here because it was from one of PEN’s eminent and active members and because it articulated ongoing questions in PEN. Gordimer’s argument did not prevail at the Berlin Congress in 2006 where an Afrikaans Center, not a Pretoria Center, was voted in though the center is based in Pretoria. The reasoning nonetheless is worth considering. The dynamics are ongoing in a number of countries and will likely continue as new centers are added or removed when they grow inactive.

Nadine Gordimer: “Let me make it clear. My objection to the formation of an Afrikaans language PEN club has no significance whatever of any kind of prejudice against my brother and sister South Africans, who are Afrikaans speakers and writers just as I am an English-speaking writer. We have eleven languages in our country. I should have exactly the same objection to the formation of an isiZulu or isiXhosa Club. We cannot have separate-but-equal (shades of apartheid) Clubs for every language, even though most of which have the strong linguistic claim of ante-dating colonially imported English and colonially created Afrikaans. I support a vigorous and linguistically open South African PEN Club, to have local representation in each region, with membership actively pursued among writers in whatever South African languages are theirs. Only such a chapter could have the strength to fulfil our needs…Historic-culturally determined circumstances give us both the necessity to overcome them and the fine opportunity to make full use of them, for our writers and our poly-literature.”

PEN is a breathing, living organization whose main body has been working around the world for a century with new members and centers joining every year as other centers at times have fallen dormant or closed. It is a fellowship of writers, of citizens in civil society holding watch over freedom of expression, linguistic diversity, over literature, and over the imagination and art by which societies flourish. Particular issues and threats change according to the times. PEN declares itself an apolitical organization, yet it is an organization whose central principle and commitment to freedom of expression sets it in the fray of politics since an early warning of a society descending into authoritarianism is the arrest of its writers and the closing down of space for free expression.

Changes in PEN leadership internationally and in centers effect the organization, but the Charter holds the whole body together. The leadership of PEN International used to reside in the President, the International Secretary and the Treasurer as the Executive, which represented the Centers’ Assembly of Delegates between two annual Congresses. The narrative of this PEN Journey has shown the change in the organization and its governance as it has grown and the world in which it operated has altered. PEN International has more than doubled in size over the last three decades to 155 centers in more than 100 countries. It now holds only one Congress a year, and the leadership is a partnership among the President, the International Secretary, the Treasurer, and an elected 7-member Board representing the Centers. Work is facilitated by an Executive Director, a position first hired in 2005, who heads the staff. Depending on the skills and experience and personality of each, the dynamic changes. In my term, I tended to be hands-on as an International Secretary. The President Jiří Gruša with whom I served was engaged as the Director of a Diplomatic Academy and had not been very active in PEN before he took the role of President. I would check in with Jiří before each monthly board meeting, explain the agenda as I saw it, ask if he wanted to add or change any items and if he wanted to attend. Jiří, a former prisoner of conscience, had lived the principles of PEN, understood them and with experience, knowledge and wit was an authentic voice on the international stage. But the day-to-day decision-making and running of the organization he largely left to me and then with the first Executive Director, the Board and the staff.

Jennifer Clement, PEN International President 2015-2021

John Ralson Saul, PEN International President 2009-2015

Jiří’s successor John Ralston Saul, former President of PEN Canada, had been a long time PEN member, active in the organization with experience in governing. He took on a much more active role as President, working with International Secretary Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) and then International Secretary Hori Takeaki (Japan PEN). John traveled the globe visiting PEN centers and government officials and taking on the issues of his period. After John, PEN elected its first woman President Jennifer Clement, former President of PEN Mexico, who took on the work, along with a special focus on the issues of women globally. She spearheaded, along with PEN’s Women Writers Committee, a Women’s Manifesto and later an Imagination Manifesto and will serve until the end of the Centenary Congress in England in 2021. Kätlin Kaldmaa (Estonian PEN) has served as International Secretary during this time along with longtime PEN member Carles Torner as Executive Director.

Unfortunately over the years as PEN’s website has been upgraded, the content has not always been exported so many of the documents and speeches and records have not followed into the digital universe. The narrative is carried in paper files which overflow in my basement and even more in PEN’s and in the memories of PEN members. My own PEN Journey has been an effort to record some of the history and offer a continuity of narrative during a particular period, through the eyes of one PEN member who has had the privilege and pleasure of standing up close for part of that history. I’ve tried to render the direction and actions. The flaws, the missteps of people, including myself, I’ve also witnessed but have largely left to the side in this narrative. My purpose has not been to be a critic nor a hagiographer, nor a novelist, but a reporter, recording the actions and the journey with a touch of personal memoir.

I will leave this journey by quoting from PEN’s Democracy of the Imagination Manifesto, unanimously passed at the 85th PEN World Congress in Manila, Philippines, October 2019:

The opening of the PEN International Charter states that literature knows no frontiers. This speaks to both real and, no less importantly, those imagined.

PEN stands against notions of national and cultural purity that seek to stop people from listening, reading and learning from each other. One of the most treacherous forms of censorship is self-censorship —where walls are built around the imagination and often raised from fear of attack.

PEN believes the imagination allows writers and readers to transcend their own place in the world to include the ideas of others. This place for some writers has been prison where the imagination has meant interior freedom and, often, survival.

The imagination is the territory of all discovery as ideas come into being as one creates them. It is often in the confluence of contradiction, found in metaphor and simile, where the most profound human experiences reside.

For almost 100 years PEN has stood for freedom of expression. PEN also stands for, and believes in, the freedom of the empathetic imagination while recognizing that many have not been the ones to tell their own stories.

PEN INTERNATIONAL UPHOLDS THE FOLLOWING PRINCIPLES:

- We defend the imagination and believe it to be as free as dreams.

- We recognize and seek to counter the limits faced by so many in telling their own stories.

- We believe the imagination accesses all human experience, and reject restrictions of time, place, or origin.

- We know attempts to control the imagination may lead to xenophobia, hatred and division.

- Literature crosses all real and imagined frontiers and is always in the realm of the universal.

Next and final installment of PEN Journey: Introduction—the Curtain Rises

Links below are to blog posts mentioning PEN after 2007. I was not writing official reports of Congresses or WiPC conferences or other events, but reflecting on PEN’s work, cases and the impact of ideas in my own monthly posts, some of which I used in writing this PEN Journey:

The Journey of Liu Xiaobo: From Dark Horse to Nobel Laureate

March 31, 2020

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

March 20, 2019

Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression

May 23, 2018

Women’s Voices Rising (Women’s Manifesto)

February 28, 2018

Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

December 7, 2017

Reclaiming Truth In Times Of Propaganda (83rd PEN Congress in Lviv, Ukraine)

September 28, 2017

“Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred”

September 8, 2017

In Turkey, a show of solidarity with writers behind bars (PEN Turkey Mission)

February 3, 2017

Power on Loan

January 23, 2017

Hope for Songs Not Prison in 2017

December 27, 2016

Building Literary Bridges: Past and Present (82nd PEN Congress in Ourense, Spain)

October 3, 2016

Call for Help inside Iran’s Evin Prison

May 23, 2016

Spring and Release

March 18, 2016

View on the Bosporus: Rights in Retreat

January 29, 2016

Democracy in Africa: Who Can Chat with Kabila?

November 30, 2015

Life instead of Death…Rationality instead of Ignorance (81st PEN Congress in Quebec, Canada)

October 23, 2015

What Are You Not Reading This Summer? (WiPC Conference in Amsterdam)

June 11, 2015

Times and Tides

November 14, 2014

PEN on the Plains of Central Asia (80th PEN Congress in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan)

October 7, 2014

Poets, Pardons and Ramadan

August 2, 2014

Women’s Progress: The Power of a Bridge…and a Double Yellow Line

March 12, 2014

Qatar: A Poet in a Desert Cell

November 1, 2013

The Last Colony?

October 15, 2013

Parallel Universe in a Glassed Concert Hall in Iceland (79th PEN Congress in Reykjavik, Iceland)

September 16, 2013

Living In and Beyond History (WiPC Conference in Krakow, Poland)

May 20, 2013

Two Voices Behind the Iron Doors

April 8, 2013

North Korean Writers in a Land of the Rising Sun (78th PEN Congress in Gyeongju, South Korea)

September 15, 2012

facebook or not?

June 28, 2012

Voices Around the World

January 30, 2012

Bridge Over the Bosporus: Citizenship on the Rise (77th PEN Congress, Belgrade, Serbia mentioned)

September 28, 2011

Tourist in Beijing: A Dance with the Censor

July 29, 2011

Ice Flows: Freedom of Expression

January 29, 2011

In the Woods: On History’s Doorstep

December 22, 2010

Full Moon Over Tokyo (76th PEN Congress in Tokyo, Japan)

September 30, 2010

Introducing Isabel Allende

May 21, 2010

“Because Writers Speak Their Minds”–2

March 31, 2010

“Because Writers Speak Their Minds”

February 24, 2010

Haitian Farewell

January 18, 2010

Yellow Geranium in a Tin Can

October 27, 2009

China at 60–Fate of Liu Xiaobo?

September 30, 2009

A Time of Hopening (WiPC Conference in Oslo, Norway)

June 24, 2009

“There Will Still Be Light” *

April 30, 2009

The Intensifying Battle Over Internet Freedom

February 24, 2009

Charter 08: Decade of the Citizen

December 30, 2008

China from the 22nd Floor (Hong Kong Conference)

May 28, 2008

OLYMPIC RELAY– A POEM ON THE MOVE

April 21, 2008

Words That Matter

March 4, 2008

PEN Journey 44: World Journey Beginning at Home

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

After PEN’s Asia and Pacific Regional meeting in Hong Kong February 2007, I flew to Tokyo for a two-day visit with members of Japanese PEN, along with International PEN board members Eric Lax and Takeaki Hori. We met with Japan PEN’s board, and in the evening I shared a stage and conversation with Mr. Hisashi Inoue, chairman of Japan PEN and one of the country’s well-known playwrights. Part of our discussions explored the possibility of Japanese PEN hosting an International PEN Congress. Only once before, in 1984, was the World Congress held in Japan.

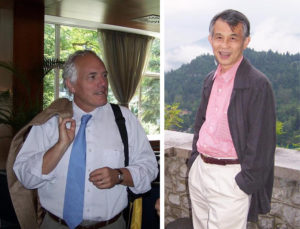

International PEN Board members Eric Lax and Takeaki Hori

Housed in an impressive building in Tokyo, Japan PEN was one of International PEN’s largest and most active centers with one of the more interesting histories. Founded in November 1935 on the eve of a tumultuous period in world affairs, Japan PEN members committed to the PEN ideals of freedom of expression and “one humanity living in peace in one world.” By 1935 Japan had left the League of Nations in the wake of the Manchurian Incident and was moving towards international isolation, a direction that concerned liberal literary figures and diplomats. In this climate International PEN in London, with support from leading novelists, poets and foreign literary figures, reached out and requested that writers in Japan form a PEN Club. Japan’s well-known novelist Toson Shimazaki served as the founding president. As suppression of free speech increased as war in the Pacific broke out and the Second World War advanced, Japanese PEN stayed in limited contact with International PEN in London and provided a unique portal to the world for its writers and citizens during that time.

Japan PEN members at PEN’s 71st Congress in Bled: Furukawa Taeko, Miyakawa Keiko and Yonehara Mari, along with Fawzia Assad (Suisse Romand PEN) Huguette de Broqueville (French PEN) and Celia Balcazar (Colombian PEN) and Takeaki Hori (PEN International Board & Japan PEN)

Personally, I remember the hospitality of Japan PEN members who took me out on the Ginza to toast my birthday as I rounded a decade. I had explained that I needed to fly home that evening, a day early to share the birthday. I still remember the glasses of pink champagne flowing up and down the Ginza, (though I was drinking sparkling water), as my own new decade was heralded, then flying halfway around the world and arriving in time to have another dinner that same night with my husband.

Three years later, in September 2010 Japan PEN hosted the 76th PEN International World Congress in Tokyo, one of PEN’s largest with representatives from 90 centers around the theme “The Environment and Literature—What Can Words Do?”

******

World War II, D-Day, the fall of the Berlin Wall—all were global events in the 20th Century which framed the history that followed for much of the world and stirred both despair and optimism among politicians and citizens and inspired stories and poetry among writers. PEN’s Peace Committee conference in March 2007 settled on three themes: Languages under Threat—Dying Cultures, Reading as a Social Event, and Post-Totalitarian Resistance.

Bled, Slovenia, setting of PEN International Peace Committee meeting, March 2007

In my files I found the keynote paper “Post-Totalitarian Resistance” by Peace Committee Chair Edvard Kovač, a portion of which I quote here. It provokes thought with the kind of open-ended questions that don’t necessarily have answers but can lead to discovery. Contents of PEN’s forums are among its important legacy.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall there was a great deal of hope that the era of totalitarian ideologies was over forever. Fukuyama and others even talked about the end of history. But ideological thinking has settled like sediment in people’s minds and it still persistently, albeit imperceptibly, affects our thoughts, conclusions and decisions.

Edvard Kovač, Chair PEN’s International’s Peace Committee, 2007

The role of the writer is to be vigilant and to recognize a transformation in the rigid thinking that until only recently stifled his creativity and pushed him towards dissidence. Perhaps he will notice that the ‘class struggle’ has been transformed and that out of this transformation the germs of new ideologies are emerging: to the legitimate striving for the creation of a Palestinian state a new anti-Semitism has been attached and alongside the right to the existence of the state of Israel the humane protection of civilian population has simply been forgotten. Recognition of and admiration for Third World culture is fortified by anti-Europeanism while a critical attitude to technological civilization confirms the ethno-centrism of the young states. The spread of democracy is confused with domination of the world market and a critical attitude to processes of globalization is interlaced with anti-Americanism. An emphasis on the need for virility conceals a kind of anti-feminism, while the emancipation of women facilitates a new uniformity. The elements of old totalitarianism which have transformed into foundations of new ideologies are harder to unmask as they appear in the name of anti-ideological principles…

…the demise of totalitarianism does not necessarily equate with critical thinking. The defeat of ideologies only creates the possibility of enlightened thinking. In fact, the desire for quick and simple solutions is even greater in post-totalitarian states. Hence the unbearable lightness of new populisms. If in the past it was politics that fully led the economy, it has now come to a complete turnaround so that the economy is stifling political initiative and economic success is putting a noose around the neck of culture and artistic creativity that cannot be marketed…

How can a writer establish a reasonable dialogue when faced with the new fundamentalisms of all colors and creeds?…this new humanism of the pen, which would once again oppose the violence of the sword (which is also the idea behind PEN’s logo) must create new means of expression. So what is the writer’s language in this new struggle?” —Edvard Kovač, Slovene PEN

There are no simple answers to these observations, but the questions continue to be worth asking in PEN’s forums.

Somewhere in the world during most weeks, if not most days, one of PEN’s 150 centers is holding an event or conference and is at work on behalf of writers. For me, the conferences and literary festivals in 2007 included a visit, along with PEN International Executive Director Caroline McCormick to New York to PEN America’s impressive World Voices Festival with over 100 writers from around the globe. The annual World Voices Festival anticipated and informed the launch of PEN International’s own Free the Word! Festival in London in 2008 and in subsequent countries thereafter.

One of the privileges of serving as International Secretary was visiting centers and members around the world though I couldn’t accept all invitations. I regret missing the celebration of PEN’s Global Library launched by members of Slovak PEN. The Global Library gathered books from PEN members worldwide in multiple languages. I missed a conference on freedom of expression and Kurdish literature and a conference in Georgia arranged by Three Seas Writers and Translators’ and the Georgia Writers Union under the auspices of UNESCO, a frequent funder for PEN gatherings. Other International PEN board members and Vice Presidents often did attend as well as the PEN members.

Visit to UNESCO headquarters. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Eugene Schoulgin (PEN International Board Member), Eric Lax (PEN International Board Member), Homero Aridjis (Mexican Ambassador to UNESCO & former PEN International President), Caroline McCormick (PEN International Executive Director)

Following the World Voices Festival, Caroline and I, along with International Board members Eugene Schoulgin and Eric Lax, met with UNESCO officials in Paris where former International PEN President Homero Aridjis was now Mexico’s Ambassador to UNESCO. The meetings at UNESCO headquarters and with Homero and the US representative to UNESCO were in anticipation of the renewal of PEN’s formal consultative relationship and “Framework Agreement” with UNESCO. In the prior agreement PEN had also been recognized as a Category II organization with ECOSOC (United Nations Economic and Social Council.) These agreements were renewed every six years; the relationship continues to this day.

One country in which PEN and UNESCO were active, but not always with compatible agendas was Turkey. Because UNESCO depended on governments for its funding and PEN frequently criticized the Turkish government for its suppression of free expression, we sometimes walked separate paths in Turkey.

The month after the UNESCO meetings I participated in Istanbul in the Forum on Freedom of Expression, sponsored by that independent organization. Along with dozens of PEN members, I had attended the first Forum on Freedom of Expression in Istanbul in 1997 as Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, and I and other PEN members had spoken at many of the biennial meetings since.

Meeting before Forum on Freedom of Expression in Istanbul. L to R: Novelist Elif Shafak (PEN case at the time), Sara Whyatt (PEN International Writers in Prison Committee Program Director), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), friend, Journalist Nadire Mater (PEN main case), Eugene Schoulgin (PEN International Board Member)

In Ankara, I was hosted at the International Ankara Short Story Days Festival, an initiative which also aspired to get UNESCO support to establish a World Short Story Day. Professor Aysu Erden, Turkish PEN’s international secretary and editorial board member of PEN International’s Diversity Project of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC) was a champion of the effort. That year the theme was “Preservation of Multiculturalism and Diversity,” a UNESCO focus as well.

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman with Aysu Erden, Turkish PEN board member

In a visit to a large school in Ankara and at a program later that evening, we considered how people and societies bridged differences, how consciousness could change in societies and how literature and stories could play a role. I reflected on the changes during the civil rights movement in the U.S. where I had grown up.

“Many of the stories in my short story collection No Marble Angels are set in the late 1950’s and 60’s in the American South during a time of upheaval in the United States. It was a time when blacks and whites peered at each other over the barriers of history and laws which separated them,” I told both audiences, aware that in Turkey, Kurds often faced discrimination as did Armenians, and the writers who wrote about this discrimination could face time in prison.

That schism is still one of the U.S.’s major national dramas though much distance has been travelled in my lifetime. The abolishment of the laws of segregation and the opening up of opportunity has strengthened U.S. society immeasurably, though there is still a journey to take. It is the closing of the distance between people which has interested me as a writer over the years, whether the distance arises from race or gender or age or simply from the self looking out into the world and seeing an image other than its own.

One of the books that had an impact on me growing up was written by another Texan who literally changed the color of his skin in an attempt to get inside the experience of being black in the South during the time when racial covenants dictated where a person could get a drink of water or sit on the bus or go to the bathroom. John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me came out when I was a school girl. I don’t remember if I read the book then, or a few years later, but when I read it, the dilemma it posed both shaped and mirrored feelings and questions which were growing in me. The questions were really questions of the human condition: Who am I? And who is that person who is not me and different from me?

For a time I considered these as political questions. I spent much of my youth debating issues of civil rights with family and friends. I located the antagonist outside myself, as some monolith, which for lack of a better description had a handle at the top, a wing on the west and several large rivers running through it. And so I left the state of Texas.

As long as the antagonist was outside in politics, society, and culture, I could separate myself from it. As a journalist in the Northeastern part of the United States, I gathered facts and statistics and social opinions and searched for answers to issues. I wrote articles on segregation and desegregation and integration of institutions in the United States. All the while other stories were building in me that I wanted to write, stories that couldn’t so easily be contained in facts and figures and social theory. I began a journey of my own, not by changing the color of my skin, but by considering experience from the inside out. I began writing fiction—short stories and novels. My writing changed from the journalistic to the consideration of the individual heart, from the objective to the subjective.

What continues to interest me in writing are the shadowy places in the individual heart, those places which keep us from seeing one another. Sometimes the distance between self and other is measured in terms of race, sometimes age, sometimes gender, sometimes culture, sometimes religion, sometimes country of origin. I’m interested in the way people go about making bridges or tearing them down.

To the extent a multicultural society recognizes the human spirit that connects its citizens at the same time valuing the cultural differences among them, the society progresses. Multiculturalism is at the heart of International PEN, which has 144 centers in 101 countries. PEN is committed to dispelling race, class and national hatreds in an effort to champion one humanity living in peace; PEN is also committed to freedom of expression.

Because we are writers, literature is our means of expression. Literature has an important role in bridging cultures. The first glimpse we have of another culture is often through reading. We let our imagination take an author’s images, scenes, and characters and bind them to our own lives. We draw from books wisdom and experience.

Many of the characters in my short stories are struggling to expand who they are and come out of themselves, to reach across to another person, to enter and occupy that space at the back of the house, that dark, vine-covered, musty room where “the other” lives. Entering that space, one raises the shades and opens the doors and windows and glimpses in the face of the other, a reflection of one’s self.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 45: Dakar—The Word, the World and Human Values

PEN Journey 43: Turkey and China—One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

January 2007 began with an assassination. The Board of PEN International was just gathering in Vienna for the first meeting of the year when board member Eugene Schoulgin got a phone call letting him know that our colleague and his friend Turkish-Armenian editor Hrant Dink, had been gunned down in Istanbul and killed. Many of us had seen Hrant at the PEN Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul in March.

Editor-in-chief of the bilingual Turkish-Armenian newspaper Agos, Dink had long advocated for reconciliation between Turks and Armenians and for Turkey’s recognition of the Armenian genocide early in the century. Dink had received death threats before and had himself been prosecuted for “denigrating Turkishness,” but as with Russian colleague Anna Politkovskaya, Dink’s assassination stunned us all and set off widespread protests in Turkey and abroad. Eventually a 17-year old Turkish nationalist was arrested and convicted, but not before police were exposed posing and smiling with the killer in front of a Turkish flag.

PEN International Board Meeting, Vienna, January 2007. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary; Jiří Gruša, International President; Caroline McCormick, Executive Director; Judy Buckrich, Women Writers Committee Chair; Elizabeth Norgdren, Finish PEN; Eugene Schoulgin, Norwegian PEN; Franca Tiberto, Search Committee Chair; Sibila Petlevski, Croatian PEN; Britta Pedersen, International Treasurer; Eric Lax, PEN USA West; Mohamed Magani, Algerian PEN; Kata Kulavkova, Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair; Frank Geary, Programs; Karen Efford, Programs.

The work of PEN is, at its heart, personal. It is writers speaking up for and trying to protect other writers so that ideas can have the freedom to flow in society. In league with other human rights organizations, PEN also advocates to change systems that allow attacks and abuse. At times the work can feel ephemeral when the systems don’t change, or make progress only to regress. However, the individual writer abides, and PEN’s connection to the writer stands.

During my tenure working with PEN, Turkey and China have been the two countries that have imprisoned the most writers. For a period both nations appeared to be advancing towards more open societies but soon retreated. In the early 2000’s as Turkey aspired to join the European Union, the country operated as a democracy with a more independent judiciary; fewer writers became entangled in the judicial processes. However, in 2007 the democratic transition in Turkey began to veer off course and has continued a downward spiral towards authoritarianism ever since.

China also promised to become a more open society with the advent of the Olympic Games in 2008. Democracy activists inside and outside of China grew hopeful. In this climate, PEN held an Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in Hong Kong in February 2007; it was PEN’s first in a Chinese-speaking area of the globe. Over 130 writers from 15 countries gathered, including writers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and many of PEN’s nine Chinese-oriented centers as well as members from Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Nepal, Australia, the Philippines, Europe, and North America.

Both China’s and Turkey’s Constitutions protected freedom of expression in theory, but in practice the protection was lacking. Instead, laws and regulations prohibited content. In Turkey, exceptions included criticism of Ataturk, expressions that threatened “unitary, secular, democratic and republican nature of the state” which in effect targeted issues around Kurds and Kurdish rights. In China, the Constitution noted that “in exercising their freedoms and rights, citizens may not infringe upon the interests of the State, of society or of the collective, or upon the lawful freedom and rights of other citizens.” The state was the arbiter.

The Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 took place at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories with programs also at Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club. The theme Writers in the Chinese World celebrated Chinese literature and a dialogue among PEN’s Asian centers and also explored issues of translation, women, exile, peace, censorship, internet publishing, freedom of expression and PEN’s strategic plan.

Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories. Over 130 writers from 20 PEN centers in 15 countries gathered for the four-day conference.

However, 20 of the 35 mainland Chinese writers who planned to attend were prevented or warned off by government authorities, including the President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) Liu Xiaobo, who later won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 while imprisoned in a Chinese jail. Qin Geng had his permit rescinded and two writers—Zan Aizong and Zhao Dagong—were stopped at the border and denied permission to exit though they had permits. (Two overseas Chinese writers who attended and had other citizenship—Gui Minhai and Yang Hengjun—are now in prison in China and are PEN main cases.)

In addition, the Chinese Communist government banned eight books, including one by Zhang Yihe, an honorary board member of the ICPC who had been invited to speak at the conference but instead was warned not to attend.

China’s promised opening of its society was already contracting, and the restrictions bore a harbinger of events to come both for writers and eventually for Hong Kong. The conference attracted wide press attention with articles in Chinese and English newspapers in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and globally via the BBC and newswire services. Renowned Shanghai playwright Sha Yexin, poet Yu Kwang-chung (Yu Guangzhong) from Taiwan and Korean poet Ko Un, short-listed for the Nobel Prize for Literature, attended. But the restrictions on the mainland Chinese writers cast an ominous shadow and grabbed the largest regional and international headlines.

“PEN has nine centers representing writers in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and abroad and has great respect for Chinese Writers and Chinese literature,” International PEN President Jiří Gruša told more than 40 reporters at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, “but we are very concerned by the restrictions on writers in mainland China to write, travel and associate freely.”

In honor of the absent writers, an empty chair sat on the platform for each session of the four-day conference.

Press Conference at Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, February 2007; L to R: Translator, Journalist Gao Yu (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Jiří Gruša (PEN International President), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary)

In 2007 more than 800 writers were under threat worldwide, and at least 33 writers were in prison in China. A number of the attendees at the conference had been imprisoned and been main cases for PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), including celebrated Korean poet Ko Un and Chinese journalist Gao Yu, both of whom addressed the conference. They knew firsthand the role of the writer in the struggle for freedom, and they knew the support PEN had given, observed one of the conference organizers Yu Zhang, General Secretary of the ICPC, half of whose members lived in mainland China.

“I am no longer afraid of anything,” one Chinese writer unable to attend said in a message to the conference. “Our bodies and our spirits are our own. To speak of ugliness and injustice we have to shout, but our throats are cut when we do.”

“We are willing for some things to be burned in the soil so a new leaf will come,” added another mainland writer in a message to the conference.

“It is important that all writers get together, and all writers protect the freedom of speech and free expression. We must write what’s in our hearts and write as a witness to history,” said Qi Jiazhen, who spent 10 years in a Chinese prison and now lived in exile.

Owen H.H. Wong of Hong Kong’s English-Speaking PEN Center pointed out that Hong Kong was a meeting point of East and West, North and South, Leftists and Rightists and Modernization and Classic writing. He noted that before the 1997 handover, Hong Kong writers saw themselves as writers in exile. Only those born in Hong Kong regarded themselves as Hong Kong writers. Now most publishing houses in Hong Kong were funded by the Communist government, and free expression in Hong Kong was threatened and controlled.

Yu Jie, a Beijing-based essayist and author and vice President of ICPC, spoke at the Foreign Correspondents Club noting that even though he was able to attend the conference and speak to the foreign media, he had not been able to get published in mainland China. For mainland writers, Hong Kong was a place where freedom of expression and freedom of the press still existed, he said. “It’s as if those of us in the mainland have our heads immersed in water and cannot breathe, but Hong Kong allows us to stick our heads above the surface of the water, and for a short time, breathe freely.”

He predicted that the authorities would later “settle the score” with the writers and publishing houses. He was in fact later arrested, tortured and imprisoned for his writing. In 2012 he emigrated to the United States.

PEN International Panel at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference. L to R: Conference organizers included Yu Zhang, (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Caroline McCormick (PEN International Executive Director), Chip Rolley (Sydney PEN)

“Existing in the unofficial nooks and crannies of an emerging civil society in China, ICPC is determined to insist that their country live up to the rights guaranteed in its Constitution,” said another conference organizer, Chip Rolley, Vice President of Sydney PEN. “This continuing work will ensure that there is indeed a turning point for PEN in China and the wider Asia and Pacific region, and that this historic conference will not dissipate like smoke.”

In his keynote address Taiwanese writer and poet Yu Kwang-chung called for “all the writers and the poets across the Chinese world” to strengthen the channels of mutual exchange, and make efforts to find a consensus on basic issues such as the formation of a common national culture (which includes in particular the establishment of joint aesthetic and literary values) in order to “make a valuable contribution to preventing war and maintaining peace.”

Attendees launched a dialogue on literature as well as on networking among PEN’s Asian centers with a regional strategy for freedom of expression and translation. The conference was part of PEN International’s program to develop the regions in which PEN operated by connecting existing writers and PEN centers and also developing new centers in countries starting to open up such as Myanmar/Burma. Often a PEN center was one of the first civil-society organization to set down roots when authoritarian controls began to relax. [A Myanmar PEN Center was established in 2013.]

In a panel on Literature and Social Responsibility panelists noted that free speech and writers’ responsibilities were the basis of social prosperity and that PEN was a bridge between writers and their responsibilities.

Participants at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference from China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Philippines, Vietnam, Nepal, including speaker Yu Kwang-chung (Taiwan) seated in center.

Chen Maiping of ICPC read a message from Zhang Yihe, the mainland novelist who was to have been on the panel but who had been prevented from attending. “There is a saying: human hearts are like water, while people’s favor and loyalty feel as heavy as mountains. During these ten plus days since my books were banned, so many people have shown their concern I have nothing to give in return for their kind support other than to express my gratitude on paper. Writing is my only means of self-expression. Writers have always been prisoners of language and words. It is not an easy affair for me to live, nor can I die in peace. I can only write…In China we talk about ‘literature as a vehicle for the Tao (the Nature, the Way).’ People have talked about this for thousands of years. However, those who have written the best literature are exactly those who never think about their social responsibility. Zhang Bojun [the author’s father who was a scholar and a minister in the Chinese government in the 1950s and persecuted during the 1957 Anti-Rightist campaign in Mao’s Cultural Revolution] was an example of this. In my view his achievements were much greater than many of the contemporary writers, artists and painters. If a writer has too strong a responsibility, he may have no achievements at all.

“For several decades, literature has been tied together with ‘revolution’ and ‘reform.’ I can’t bear such responsibility. I can only recall the past. I do not have such social responsibility tied to ‘revolution‘ and ‘reform.’ I am out of date. There are so many people singing praise for the society, why not allow an old woman like me to sing a little song of my own. I am only a piece of withered leaf. I hope that I can decay quickly so that I may become a new leaf soon. “

Chen Maiping also read “Writing in Anger” by Liu Shu, another mainland writer prevented from attending. “The conflicts between our hearts and reality and an unwillingness to keep silent are the driving forces for my writing. The disgraceful politics have turned us into dissident writers. Chinese dissident writers write in isolation. The marginalized position of dissident writers has marginalized their writing. This is very different from the West. The Eastern people have the ability to suffer and digest their sufferings. This kind of ability enables writers to ignore the reality and to become numb to the suffering of their people. They choose to write only about ‘pleasant things to lighten the load on their hearts.’

“The cruelty of reality fills their lives with ‘submission.’ The writers are swollen and weighed down with humiliations and sufferings; they have lost the anger created by their reality. They have no anger at the past, nor do they imagine a future. They only write about meaningless, shallow and trivial affairs. My anger comes from my refusal to accept and make peace with this reality. I have been detained four times because of my ideas. We puzzle over social phenomena but we long for peace. The way to calm our anger is to write…I must speak for citizens who were screened by the totalitarian society, by the police and the ugly society…we do not want to be silent. Like Lu Xun said, life is ourselves: everybody is responsible for his own life. Our flesh body and our life are in exile in our homeland, until we disappear.”

Women Writers Committee gathering at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference including Chair Judy Buckrich in turquoise in center.

Women participants at the conference focused in addition on the restrictions for women writers in the region.

Qi Jiazhen was imprisoned 10 years and accused of trying to overthrow the government after she inquired whether she could study aboard. She said she had been young and inexperienced and felt guilty and wrong, the same feeling shared by other women. Gender awareness was low in China, she said. She now lives in Melbourne, Australia.

Celebrated mainland journalist Gao Yu confirmed two kinds of prisoners in China—special treatment prisoners & prisoners of conscience. As vice chief editor of an economic weekly with an international reputation, she was a special treatment prisoner. She had treatment when she was sick and had to do little hard manual work because was already 50 and given 7 years in prison. But she never admitted her wrong doing so she didn’t enjoy any pain reductions, she said.

Chinese journalist and PEN main case Gao Yu with translator.

In a panel on Censorship and Self-Censorship, Gao Yu noted that censorship began at school where children learned to protest injustice when not treated fairly. Later in life that grew into resistance of the system. The writer who sought to express truth experienced censorship which could lead to punishment and prison. But that was not as frightening as being silent, she said. The essence of being a writer was to have integrity and speak the truth.

After the conference, a dozen police picked up one participant and took him to a hotel room to find out what the conference had been about. A poet and member of ICPC, he told the police, “To build a ‘harmonious society’ and ‘harmonious culture’ [as President Hu Jintao has called for], writers should sit with writers and not always have to sit with policemen.” He was finally released after hours of interrogation.

One of the more creative campaign tools planned during the conference was spearheaded by a team of PEN Centers in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia. The members developed a digital relay with Chinese poet Shi Tao’s poem June. The poem tracked the path of the Olympic torch across a digital map. Shi Tao was serving a 10-year prison sentence for sharing with pro-democracy websites a government directive for Chinese media to downplay the 15th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests. His emails had been turned over to the Chinese government as evidence by Yahoo. His poem commemorated the Tiananmen Square massacre and was translated and read in the languages of PEN’s centers around the world, including in regional dialects as well as in the major languages. Ultimately 110 of PEN’s 145 centers participated and translated the poem into 100 languages, including Swahili, Igbo, Krio, Tsotsil, Mayan. The poem’s journey began on March 30, 2008 in Athens and traveled to every region on the online map, arriving in Hong Kong on May 2 and in June to Tibet where it was translated into Tibetan and the proposed Uyghur PEN center translated it into Uyghur. Finally August 6-8 it arrived in Beijing where it was translated and read in Mandarin. Anyone could click on the map and hear the poem in the language of the country designated.

By the 2008 Olympic Games 39 writers remained in prison in China.

June

By Shi Tao

My whole life

Will never get past ‘June’

June, when my heart died

When my poetry died

When my lover

Died in romance’s pool of blood

June, the scorching sun burns open my skin

Revealing the true nature of my wound

June, the fish swims out of the blood-red sea

Toward another place to hibernate

June, the earth shifts, the rivers fall silent

Piled up letters unable to be delivered dead.

(Translated by Chip Rolley)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 44: World Journey Beginning at Home

PEN Journey 35: Turkey Again: Global Right to Free Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN’s work attests to the power of the individual and also to a particular vision of globalization that advocates the global right to free expression, a right that supersedes national restrictions.

In February 2005 Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s most noted writers, received threats and had his books burned by nationalist groups objecting to comments he made to a Swiss magazine while he was abroad. He referred to an Armenian “genocide.” While the Armenian community rallied to defend him, their support heightened certain nationalists’ protest in Turkey. Orhan wasn’t in Turkey at the time and hoped the turmoil would die down, but a government official in southern Turkey ordered the seizing of his books from local libraries so that they could be destroyed; it turned out later that there were none of his books in those libraries.

Novelist Orhan Pamuk and Sara Whyatt, International PEN Director of Writers in Prison Committee (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At Pamuk’s request International PEN kept quiet publicly at first. In mid-April Sara Whyatt, International PEN’s Director of the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) and I had lunch with Orhan in London to discuss how PEN could help if the threat escalated. I was International Secretary of PEN at the time. We agreed that publicity at this stage could exacerbate the situation; however, we explained that PEN centers could work behind the scenes by direct contacts with their governments, and PEN would be prepared to step into public action should the need arise.

Pamuk intended to stay outside Turkey until late April/early May, but then he would be returning home to Istanbul. Sara stayed in touch with him and shared a plan for action if the threats resumed on his return. Meanwhile we told him PEN would continue to lobby for a change in the Turkish Penal Code that allowed the charges. Key PEN centers, who had good relations with their own governments, and centers from countries with influence in Turkey would make approaches. London’s WiPC would make similar approaches to Turkish officials in Ankara and also through mechanisms at the United Nations, OSCE, and the European Union (EU). At the time Turkey was hoping to become a member of the EU and was attempting to align its judiciary codes with those required by the EU. PEN also worked with the International Publishers Association .

PEN prepared a statement on the situation in Turkey from early 2005 and kept it updated with news and recommended actions for the over dozen PEN centers ready to respond on this case. There was also press guidance should the centers receive queries. Meanwhile PEN continued to work on the other cases of over 70 writers and intellectuals charged or in prison in Turkey, which had long been a country with a revolving door of writers harassed, detained, attacked and sent to prison.

On April 1, 2005 World Peace Day the Turkish press reported:

The investigation against author Orhan Pamuk due to this statement saying, ‘One million Armenians and 30,000 Kurds were killed’ [in Turkey] has ended with a case in which he is accused of violating article 301 of the new Penal Code (same as famous article 159 in the former one) “Insulting Turkish nationality” and with the demand of being imprisoned between six months and three years. The first hearing will take place at Istanbul Sisli No. 2 First Instant Criminal Court on December 16, 2005.

The Public Prosecutor claimed that Pamuk’s remarks in Switzerland’s Das Magazin were an infringement of Article 301/1 of the Turkish Penal Code which states that “the public denigration of Turkish identity” is a crime and that those found guilty should be given sentences ranging from 6-36 months.

With threats renewed by the Public Prosecutor and a lawsuit filed against Pamuk that could result in a three-year prison term, Orhan finally gave PEN the green light to launch its campaign. PEN centers mobilized globally, including in Turkey.

“It is a disturbing development when an official of the government brings criminal charges against a writer for a statement made in another country, a country where freedom of expression is allowed and protected by law,” I noted at the time.

Pamuk’s hearing in December, 2005 was approximately ten years after renowned Turkish writer Yaşar Kemal had been called to trial on similar charges in January 1995. Pamuk told a colleague he would underline two things in his statement:

1. What I said is not an insult, but the truth.

2. What if I were wrong? Right or wrong, do not people have the right to express their ideas peacefully in this Turkey?

Eugene Schoulgin, PEN International Board Member and Müge Sökmen (Turkish PEN) at WiPC Conference, Istanbul, 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the judicial hearing, PEN members came to stand witness to the proceedings, including WiPC Chair Karin Clark, Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar, and International PEN board member and former WiPC Chair Eugene Schoulgin. Armored police officers escorted Orhan as protesters hurled a barrage of eggs and jumped on the car, punching the windshield.

PEN’s observers reported at the time: “The scenes around the first appearance of Orhan Pamuk before Sisli No. 2 Court of First Instance on 16 December 2005 at 11:00 were marked by constant shouting and scuffling turning ugly and violent at times. As those attending the proceedings left the court, eggs were hurled along with insults from the nationalists and fascists among the crowd lining the pavement across the street. This in full sight of the national and international media which had turned out in full…

“The courtroom was packed with well over 70 people—among them famous Turkish writers such as Yaşar Kemal and Arif Damar, and representatives of the European Parliament, several diplomats, members of Turkish and international freedom of speech organizations. The aggression and heckling inside and outside the court did not abate…”

The session ended after an hour and 15 minutes with an adjournment because the Ministry of Justice said that it needed more time to decide on the legal basis of the trial.

Hearing the news of postponement, International PEN President Jiří Gruša declared, “It is unbelievable that Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s best known and eminent authors, is in this situation. What it indicates is a complete disregard for the right to freedom of expression not only for Pamuk, but also for the Turkish populace as a whole. This decision bodes ill for other writers who are being tried under similar laws.”

He added, “PEN demands that the trials against all writers, publishers and journalists be halted and that the laws under which they are being tried be removed from the Penal Code. We also call on the Turkish authorities to put a definitive end to the penalization of those who exercise their right to freedom of expression.”

Hrant Dink, Journalist and Editor-in-chief Argos and Hilde Keteleer (Belgian Flemish PEN) at PEN WiPC Conference in Istanbul, Spring 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the time there were 14 other writers, publishers and journalists on trial under the newly revised “insult” law for criticizing the Turkish state and its officials. These included Ragip Zarakolu, publisher of books by Armenian authors and Hrant Dink, editor of an Armenian language newspaper, who was assassinated two years later.

For Pamuk the charges were dropped in January 2006, though on a technicality rather than on legal grounds protecting freedom of expression. The widespread opposition to Pamuk’s prosecution by PEN and other organizations succeeded, but as Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar noted in The New York Times: “There are many people abroad who fail to see beyond Orhan Pamuk’s trial. Saving a writer like Orhan Pamuk from prosecution may stand as a symbolic example on its own. But it is not an overall resolution for other intellectuals and writers that still face similar charges in Turkey.”

In March 2006 Orhan was the featured guest at PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee’s biennial conference held in Istanbul, hosted by Turkish PEN.

Writers in Prison Conference Istanbul 2006. L to R: Karin Clark (International PEN Chair WiPC), Sara Whyatt (Director WiPC), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary International PEN), and Sara Wyatt (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

On October 12, 2006 Orhan Pamuk won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

It could be said that the case of Orhan Pamuk signaled a long ride to the end of Turkey’s potential membership in the EU. In September 2006 the European Parliament called for the abolition of laws such as Article 301 “which threaten Europe’s free speech norms.” In 2008, the law was reformed, but according to the reform, it remained a crime to explicitly insult the “Turkish nation” rather than “Turkishness,” and in order to open a court case based on Article 301, a prosecutor was required to have approval of the Justice Minister; a maximum punishment was reduced to two years in jail. In November 2016 the members of the European Parliament voted to suspend negotiations with Turkey over human rights and rule of law concerns. In February 2019 the European Union Parliament committee voted to suspend accession talks with Turkey.

Turkey continues to be one of the most problematic countries for writers, especially on certain topics. While Turkey’s Penal Code relaxed for a while, allowing more space and freedom for writers, in the last years, the code and its execution has grown more onerous than ever.

*****

In that spring of 2005, I attended an event celebrating Press Freedom Day (May 3), hosted by Italian PEN in Venice. There I shared testimonials from writers on whose behalf PEN had worked. I share these again here:

** Cuban journalist and poet Jorge Olivera Castillo was conditionally released from prison in December 2004 after serving 20 months of an 18-year sentence. He wrote:

Your solidarity has been a light in the darkness. Thank you for having elected me as an Honorary Member…[I send] to all of you my gratitude for your messages of support and your unflagging concern.

** Nkwazi Mhango, Tanzanian journalist in exile, wrote:

Believe it or not tears are gushing as I am writing this message. No way in whatsoever manner my family and I can reciprocate your love and commitment to our plight. THANKS AGAIN AND AGAIN AND AGAIN MORE.

** On a sadder note the following was received from Tunisian internet writer Zouhair Yahyaoui, who died suddenly in March 2005 from a heart attack after he’d been released from prison:

Your email gave me once again a lot of hope for a better future in my country at a time when the dictatorship uses all illegal and barbaric means to make us give up and abandon all forms of protest…The fact that I continue to struggle to obtain our right to freedom of expression, here in Tunisia, is thanks to support of members of International PEN and other international organizations. Thank you again to you, to the Writers in Prison committee of International PEN and to all the PEN clubs all over the world who have supported me enormously during my imprisonment and who continue to do so.

** And from Chinese writer Jiang Qisheng:

… I am not a remarkable person. I am just an ordinary guy who did something extraordinary because it was the right thing to do…If my own case has any special significance it is only that it forces people to face a highly embarrassing fact—the fact that even now, in the dawn of the 21st century, a Chinese citizen can be imprisoned for what he says.

** I ended with a passage from the book This Prison Where I Live, the collection of prison writings drawn together by International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. In the afterword Malawian poet Jack Mapanje, who himself was in prison during the autocratic rule in his country, tells how bits of news managed to get smuggled into him in his concrete cell filled with spiders and cockroaches, scorpions and bats and bat droppings.

I found the note, unusually fat…I found a bulletin of typed world news and two poems by Brecht…Pat also enclosed two honorary membership cards from International PEN’s English and American centers, issued in London and New York respectively. They each bore my name. I had been made a member of PEN. Well, well, well!…

Then there was a cutting from Britain’s Guardian newspaper. Lord Almighty! A picture of Ronald Harwood, Harold Pinter, Antonia Fraser, and other members of English PEN reading from my book of poems in protest at the Malawi High Commission in London! It must sure have an effect, I thought. Ten thousand miles away, among the cockroaches of the prison where I lived I felt utterly humbled. Shattered. Such generosity, such warmth I surely did not deserve. All for one slim volume of poems? Why hadn’t I written more poems? I was dumbstruck. Despair vanquished. ‘I am belonged,’ I heard myself whisper.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 36: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part One

PEN Journey 32: London Headquarters: Coming to Grips

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN is a work in progress. It has always been a work in progress during its 100 years. Governing an organization with centers and members spread across the globe in over 100 countries can be like changing clothes, writing a novel and balancing a complex checkbook all while hang gliding. Perhaps an exaggeration, but not by much.

In 2004 the leadership of President and International Secretary were at the center of the governing structure along with the Treasurer and a relatively new Board. The President represented PEN in international forums. The International Secretary was tasked with overseeing the office and the centers of PEN and with any tasks the President handed over like running board meetings and setting up the agenda for work. The concept was that PEN should be able to elect as President a writer of international stature to represent PEN in global forums but not have the obligation to run the organization. That could be the role of the International Secretary, along with the Board and staff.

When I assumed the role of International Secretary, PEN did not yet have an executive director, though the consensus had built from the strategic planning process that we needed one. Both the President and International Secretary were volunteer, unpaid positions, which meant they were not full time. At the post-Congress board meeting after Tromsø, we agreed to begin a search for an executive director.

I suggested monthly board meetings, which had not been the practice. We could do these by phone, which meant there were only a few hours a day when everyone would be awake. If Judith Rodriguez in Melbourne, Australia could stay up past 11pm and Eric Lax in Los Angeles didn’t mind waking up at 7am, the rest of us—Takeaki Hori in Japan, Sibila Petlevski in Croatia, Eugene Schoulgin in Norway, Elisabeth Nordgren in Finland, Cecilia Balcazar in Colombia as well as President Jiří Gruša when he joined from Vienna or Prague and me in Washington, DC or London—could find our time zone and call in. The technology was not as sophisticated as today, and we didn’t yet use skype so the calls were not cheap, but we began to manage each month.

International PEN President Jiří Gruša

As International Secretary, I was in charge of overseeing the office and staff, working with centers on conferences and projects and along with Jiří, liaising with our partners like UNESCO. Administrative Director Jane Spender and I drew up the agenda for each board meeting. I always checked with Jiří to see if he had items to add and to see if he wanted to join the board meeting. I chaired most of the board meetings and much of the Assembly of Delegates at the Congresses. English was not Jiří’s first or second language, and he had other large obligations. During his presidency, he took on the Directorship of the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna, where we held our winter board meetings. This division of tasks between Jiří and me was quite different when the next President John Ralston Saul took on the presidency in 2009, along with Takeaki Hori as International Secretary. John was a much more hands-on President than Jiří. The President and International Secretary were a team and usually agreed between them who would do what.

One of my most important and enjoyable partnerships was with Administrative Director Jane Spender, who was promoted to Program Director for Jane had been instrumental in the thinking and execution of PEN International programs first years. I tried to spend at least a week to 10 days each month in London or on the road for PEN. I was able to finance my travel outside of PEN’s budget. Jane and I worked closely together as we outlined what yet needed to be done in PEN’s move to modernize systems. Each International Secretary had operated in a way that worked for the time. In my tribute to retiring international Secretary Terry Carlbom, I’d noted that early in PEN’s life, around 1924 at a meeting in Vienna, the French representative had turned to the German representative and said, “PEN means Paix Entre Nous (“Peace between us.”).* Members did not always agree with each other and would perhaps even get angry, but the hope was that members would honor and serve that acronym well.

L to R: International PEN Program Director Jane Spender and PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman at the wall surrounding Diyarbakir, Turkey in March, 2005.

After Terry debriefed me at the PEN Congress in Tromsø, one of my first visits was to Paris to talk with former International Secretary Alexander Blokh, who had held the position for 17 years, to listen to his experience. The times and the demands were changing from Alex’s day as PEN grew and as the world sped up and shrank at the same time with the advent of the internet.

One of my early calls was to George Gawlinski, who had taken PEN through the strategic planning process in Bellagio in 2003 (see PEN Journey 28). George’s advice was that we hire an interim executive director while we did a search for an executive director. He said he happened to know that one of the best in that business was available, a man named Peter Firkin. He could come in, help us get systems in place like employment policies which we didn’t have, a budget which we didn’t have and help set up the systems the office would need to appeal to a first rate executive director and also begin relieving the impossible workload Jane and the staff bore. Jane and I interviewed Peter together. After about twenty minutes (or less), we exchanged relieved glances over the table and knew we had found who we needed for that moment.

A grey-haired New Zealander with wide experience with organizations and a love for books, Peter spoke with the Board and Jiří, and PEN hired him to come in several days a week to begin helping, including assisting in the search process. My notebook of lists had already grown quite full, and now these lists Jane and I allocated among the three of us. One of the big tasks was to develop an overall budget for the organization. The Writers in Prison Committee operated with a budget, but the rest of the organization operated project by project and at the end of the year, a list of expenses and income was recorded. There was not a budget projected forward for the whole organization, rather an accounting of money spent and money received. The only way to draw up PEN’s first budget was to look at what was spent the year before and project forward. The budgeting processes also needed to be set in place. American PEN sent over its financial director to work with the London office for a week with Jane and Peter and the Treasurer Britta Junge Pedersen and bookkeeper Kathy Barazetti. It took a while, but we eventually had a comprehensive, estimated budget for the whole organization.

Another task was to revise our status with the British Charity Commission, which oversaw all charities in Britain. The work of human rights organizations had been regarded as being political in nature, therefore not permitted charitable funds. Some organizations like International PEN had set up charitable trusts—the International PEN Foundation—to raise funds for their educational work. But with a change in the law, human rights organizations were now accepted as a-political. With Peter’s help we found a law firm that could take us through the process to dissolve the International PEN Foundation so International PEN could operate as one charitable organization.

We also found new and highly respected auditors. All these were the nuts and bolts on the continued journey to improve and modernize International PEN. During Terry Carlbom’s tenure as International Secretary, we had gotten rules and regulations and procedures updated and approved and the strategic planning process underway. The tasks and lists to get International PEN operating more efficiently seemed endless, but each day Jane and I checked more items off the lists.