Posts Tagged ‘Afghan PEN’

PEN Journey 29: Mexico City and the Road Ahead—Part I, Form

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

A PEN International World Congress is a hybrid—a mini-UN General Assembly with delegates sitting at tables behind their center’s (and often country’s) name plates discussing world affairs that relate to writers; an academic conference with panelists addressing abstract philosophical themes; a literary festival with writers reading their poetry and stories and sharing books, and finally a civic engagement with resolutions passed on global issues which are then delivered, sometimes by a march or candlelight vigil to a country’s embassy that is oppressing writers.

Heads of state and UN officials frequently visit and/or speak at PEN Congresses depending on the openness of the host country; esteemed writers, including Nobel laureates, and former PEN main cases are often guests. The Congress’ size varies depending on the resources available, but the financial commitment is out of reach for many PEN Centers.

PEN International 69th Congress 2003. L to R: PEN main case General José Francisco Gallardo and family; Homero Aridjis, PEN International President; Terry Carlbom, PEN International Secretary; Nadine Gordimer, PEN International Vice President. (photo courtesy of Sara Whyatt)

The 2003 International PEN Congress in Mexico City was celebrated as the First Congress of the Americas. Hosted by Mexican PEN, it was also supported by Canadian PEN, Quebecois PEN, American PEN, and the Latin American PEN Foundation. It was the final Congress under the presidency of Mexican poet and novelist Homero Aridjis. Organized around the theme of “Cultural Diversity and Freedom of Expression,” the 69th Congress welcomed delegates from 72 PEN Centers from every continent except Antarctica. At the Assembly six new centers were admitted—Afghanistan, Morocco, Paraguay, Spain, Trieste, and Zambia; three dormant centers—Chilean, Kenyan and German-speaking Writers Abroad—were reinstated as active.

PEN International First Congress of the Americas 2003 in Mexico City. Theme: Cultural Diversity and Freedom of Expression

The admission of new centers was especially celebratory because of the number and the variety, leading with Afghanistan. Two delegates—a man and a woman—had traveled from Kabul in spite of the conflict in the country. Eugene Schoulgin, chair of the Writers in Prison Committee and member of Norwegian PEN, had visited Afghanistan twice that year along with Norwegian PEN member Elisabeth Eide. Eugene told the Assembly how impressed they were by the courage and vitality of the Afghan writers. “For them, after so many years of war, it was extremely important to open a window to the world through which they could look outwards and through which others could be introduced to their rich literature and culture and become friends in this tormented part of the world.”

Twenty Afghan writers had rented space in Kabul for a writers house, signed the PEN Charter and sent it to London with their membership application. (Less than a decade later there were 1000 members of Afghan PEN.) The Afghan delegate Partaw Naderi told the Assembly in order to reflect the major languages and communities in Afghanistan, the center planned to have a Pashtun language section, a Persian language section, and a section for Uzbek, Turkmen and other local people. In the last three decades writers had become refugees, mainly in Pakistan and Iran and some in the West, he said. Now one of the cultural centers in Kabul was ready to publish work by some of them though “freedom of expression was very, very limited” with frequent attacks and killings of writers and journalists. He had made the long trip to attend PEN’s Congress in order “to be among kind people,” and he profoundly wished for democracy and freedom of speech in Afghanistan.

Alexander Tkachenko of Russian PEN and a PEN International Board member observed that the Soviet Union had brought great trouble for 20 years to the Afghan people, their culture and literature, and he apologized for this and gave support to the new PEN center.

In response, Safia Siddiqi, the second Afghan delegate, said writers were not enemies; it was the governments. “Pens did not kill people, pens constructed things and helped people to join together in friendship,” she said, urging “their brother from Russia,” not to feel that writers were ever the enemy of each other. Thanking all who had made this trip possible, she noted it was also important that women participate and overcome restrictions and cross boundaries to come to places like Mexico.

Every new PEN center has its own story and mandate. I expand here on only one more at the Mexican Congress because that center’s raison d’etre also represented a change that was about to be voted on regarding PEN’s Charter.

The Trieste Center’s organizing principle was not nationality—it was located in Northern Italy—nor a single language—the writers spoke and wrote in Italian and many other languages—but culture as an organizing principle. The majority of PEN Centers were formed around geographic and national locations such as the new Morocco, Paraguay and Zambian centers. Countries can have as many as five centers if the nation is large like Russia, China and the U.S. or if there are multiple languages originating within its borders such as Spain which now had three centers—Catalan, Galician and Spanish centers or like Switzerland which had four centers—Swiss Romand, Swiss German, Swiss Italian-Reto-Romanish, and Esperanto. A few centers were formed in exile when the host country was not free enough for a PEN Center like Vietnamese Writers Abroad or Cuban Writers in Exile centers.

The Trieste Center was unusual. Endorsing the new center, Giorgio Silfer of Esperanto PEN observed that PEN centers did not represent nations; they represented literature, and literature did not need a nation to give it identity—as was the case with Yiddish, Roma and Esperanto. Literature established its own territory, and when a language was dead, its literature was simply and only an expression of connection with memory, he said. Trieste was a unique place, a cosmopolitan city: its writers in Italian were the expression of a culture that was not exactly Italian culture, but which incorporated expressions from other linguistic traditions.

Tone Persak of Slovene PEN added that Trieste had been “the town in the open space, on the open wind.” There had been extraordinary writers in different languages there: Italian, Slovene, English, Spanish, Croatian, Serbian, Yiddish, German, Friulian and so on. James Joyce, Rainer Maria Rilke, Italo Svevo, Juan Octavio Prenz. It had been a town of many conflicts but also the town of the cohabitation of different cultures.

PEN International’s Charter before amendments in earlier brochure

Serbian delegate Vida Ognjenović and Croatian delegate and PEN International Board member Sibila Petlevski highlighted the multilingualism in Trieste and observed that the current situation after many, many Balkan wars had created an environment in Trieste where a PEN Center whose members came from different nations could cooperate with the Italian Center and all the other Centers in the region and give rise to new ideas. The Trieste Center was accepted.

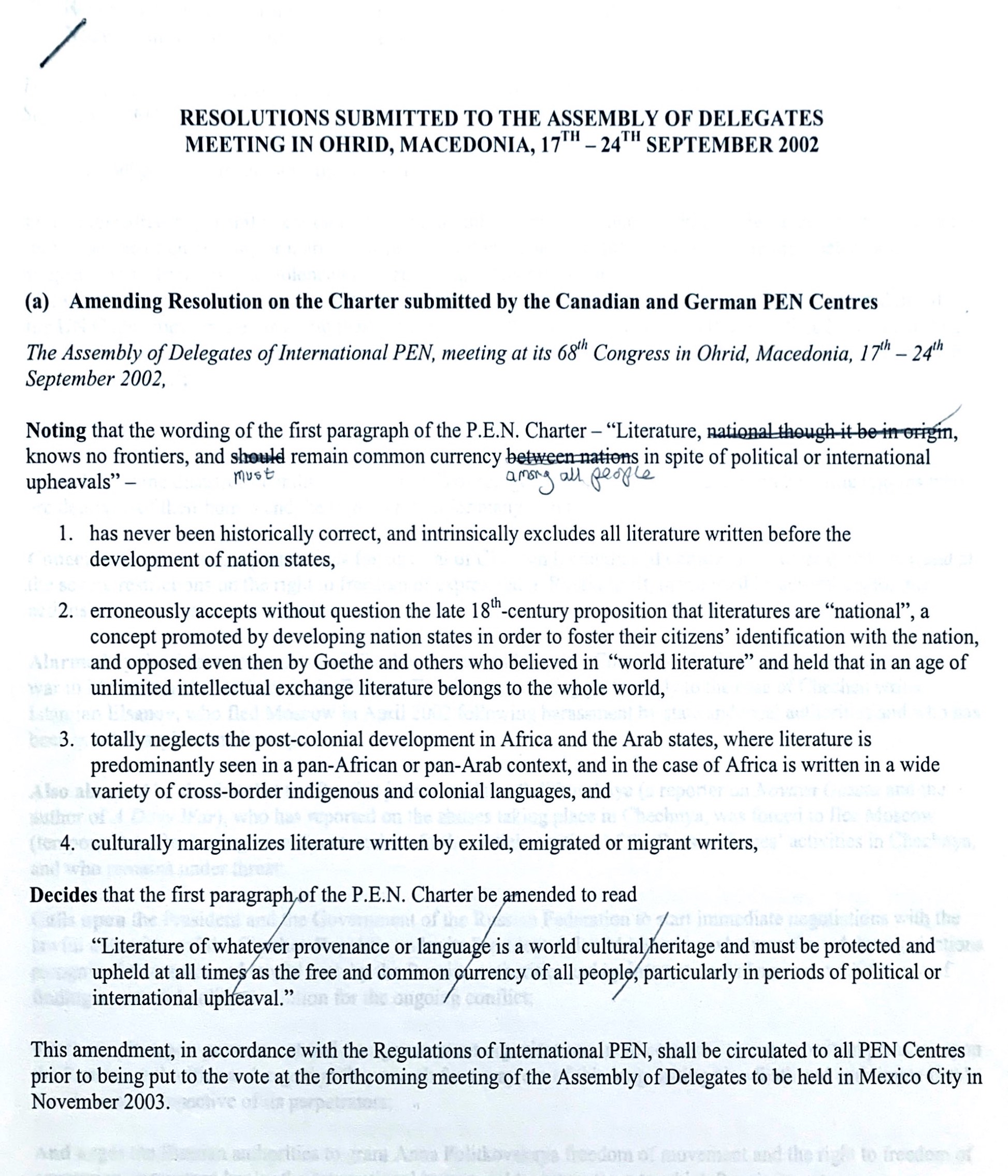

The following day an amendment to PEN’s Charter was approved, the first change to this central document since the Charter’s text was agreed at the 1948 Copenhagen Congress. Literature’s origin beyond nationality informed the amendment which had been presented at the 2002 Macedonian Congress and vetted over the past year. The revision was a simple deletion of words. The Charter’s first item would now read: “Literature [deleted “national though it be in origin”] knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.”

At the Mexico Congress another amendment was proposed and discussed for the fourth item in the Charter and would have a year for further consultation. The vote would come at the 2004 Congress. Both amendments involved a fine-tuning of words, reflected in the many pages of minutes, and an attention and passion for language and the translation of language which only a gathering of writers would have patience for.

These amendments and the changes proposed for the Regulations that evolved in the strategic planning process were shepherded by the International Secretary Terry Carlbom and especially by the Administrative Director Jane Spender whose patience and humor and intelligence kept everyone on track. The laborious task of taking more than 130 delegates through 30 Articles, often with subsets, fell to PEN International Board Member Eric Lax whose Sisyphean patience and care led the Assembly item by item. Ultimately all the recommended changes to the governance and structure of International PEN were approved.

The highlights involved the role and authority of the International PEN Foundation which focused on gathering resources for PEN and whose trustees had a voice on the Board but were also governed by the Board; the roles and authority of the International Secretary, the President and Board. The International President was to be a “distinguished writer of international literary reputation,” and the International Secretary was to have “actively participated in the affairs of International PEN” and was given a vote on the Board. These relationships were a moving target and would remain so over the years to come. In 2003 the President was given the discretion to lead and chair the Board and the Assembly but not the obligation so the role would depend on who occupied the office. A more formal Search Committee was established to seek out candidates for the positions of President, International Secretary and Board and to be elected by the Assembly on nomination by the Board. Chairs of both standing and special committees could attend regular board meetings but had no vote.

Deputy Chair of the Board Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN) reported to the Assembly that the first Aim of the Strategic Plan, “Building the community of writers” included the item “expand PEN’s presence around the world and, in doing so, develop its humanitarian and cultural mission.” PEN was now pursuing a policy of cooperation with other organizations, initiated by the International Secretary’s signing of a cooperation agreement between International PEN and the European-Pacific Congress Alliance. The full Strategic Planning document would continue through a consultative process with the centers and be on the agenda for approval at the 2004 Congress in Tromso, Norway.

Parsing through, revising, getting approval of strategic plans and regulations for an organization as complex and diverse as PEN was a tedious but necessary task and reminded me of the book title “The Anarchists’ Convention.” Though rules and regulations and strategic plans would change in the years ahead, the Mexico Congress document was a base from which PEN grew and shape-shifted. Those who sat in the large Fiesta Americana ballroom can perhaps still hear Eric’s patient voice: “And now turn to Article 23…Comments…There being no further discussion, Article 23 is approved. Now turn to Article 24…”

Next Installment: PEN Journey 29: Mexico City and the Road Ahead—Part II, Substance

PEN Journey 26: Macedonia—Old and New Millennium

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I remember diving from a rowboat into Lake Ohrid and swimming in pristine water. I love to swim but never did so at PEN Congresses. However, the 68th Congress was held on one of Europe’s oldest—3 million years old—and deepest lakes which floated in the mountainous region between North Macedonia and eastern Albania. The water was the cleanest I had ever seen or felt. I swam without looking back until finally, I heard a voice from the boat shouting, “Come back! You’re almost in Albania!”

Moments before Isobel Harry (l) (Canadian PEN) and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (r) (American PEN) dive into Lake Ohrid for a swim between meetings at the 68th PEN Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia in 2002

Albania, or rather the Albanian Liberation Army, a paramilitary organization, had recently been in conflict in Macedonia and was the reason PEN’s Congress there had been postponed the year before. (PEN Journey 25)

Swimming with me was my friend Isobel Harry, Executive Director of Canadian PEN, and in the boat sat Cecilia Balcazar from Colombian PEN and another PEN member. They watched over us in this break from the PEN meetings. My memories of the 2002 PEN Macedonia Congress include intense meetings of the Assembly in the Congress Hall of the old Soviet-style Metropol Hotel and neighboring Bellevue Hotel conference center and relaxed gatherings afterwards at lakeside cafes in the town of Ohrid, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

PEN colleagues at a lakeside cafe during the PEN Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia. (L to R) Dixie Willis and Sara Whyatt (WiPC staff), Susie Nicklin (English PEN), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN & WiPC Chair), PEN member, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Vice President & American PEN), Niels Barfoed (Danish PEN), Isobel Harry (Canadian PEN), Fawzia Assaad (Swiss Romand PEN), Victoria Glendinning (English PEN), Carles Torner (PEN Board & Catalan PEN)

In the evenings we gathered for literary events with UNESCO-like titles—The Future of Language/Language of the Future and Borders of Freedom/Freedom of Borders. These were also the themes of the Congress. There was music and poetry in Macedonian and other languages I didn’t understand, recited in cavernous, shadowy chambers, including in the ancient Cathedral Church of St. Sophia, a structure from medieval times, rebuilt in the 10th century. Its frescoes still adorned the walls from Byzantine times in the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries and had been restored after the church was converted to a mosque during the Ottoman Empire.

While current politics and conflicts occupied the daytime work of PEN, history suffused the gathering. Civilization in Ohrid dated to 353 BC when the town had been known as “the city of light.”

Cathedral Church of St. Sophia in Ohrid

“The old millennium, especially in ‘old’ Europe, should, I believe, be left behind with all its anachronistic boundaries—geographical, historical, racial, ethnic, state, linguistic, religious and cultural—and give way to the unfolding of the new millennium, to its open-mindedness and tolerance,” Dimitar Baševski, President of Macedonian PEN, wrote in his introduction to the Congress. “For generations we in Macedonia have lived with a creed according to which culture and not warfare or power is perceived as the field for competitiveness among nations. The aims of the World Congress of International P.E.N. in 2002 perfectly correspond with the spirit of this creed.”

Over 300 people from 69 PEN Centers gathered in the hills of this North Macedonian city for the 68th World Congress. The Congress’ work included the activities and reports of PEN’s committees—Writers in Prison, Peace, Translation and Linguistic Rights, Women’s, Exile Network—and the PEN Foundation, PEN International Magazine, and PEN Emergency Fund. There was a proposed revision to PEN’s Charter removing the concept of literature as being national in origin; there was the introduction of new centers, the dissolution of inactive centers and the elections for the Board, Vice Presidents, and Search Committee. There was a report from the International Secretary on the renewal of PEN’s “formal consultative relations” with UNESCO for a further six years, a step that acknowledged PEN as the only voluntary organization and the only literary organization in this category and one of only 12 organizations with a “Framework Agreement.” PEN had also been reclassified as a Category II organization with ECOSOC (United Nations Economic and Social Council) which included organizations with “special competence in specific areas” such as Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, a category that reflected PEN’s status and contribution as the only world writers organization within the UN system. At PEN’s Assembly of Delegates attention was called to a dozen PEN conferences—last year’s and the year ahead—and finally the Assembly passed Resolutions from the Writers in Prison Committee and Peace Committee on the situations in Russia and Chechnya, Russia itself, the Middle East, Belorussia, China, Colombia, Cuba, Iran, Turkey, Zimbabwe, Uighur Writers, and Tatarstan

The aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on the United States the year before remained a focus that was altering the security landscape for nations around the world and for writers. PEN President Homero Aridjis observed, “Today our world is teetering on the brink of war.” He added, “In search of security, there have been encroachments on privacy and intrusive measures threatening freedom of expression and the right to dissent and criticize, but the global reach of information seems to have accelerated, proof of which is the current effort by the Chinese government to block its citizens’ access to the search-engine Google.”

“How can PEN and writers bring about positive changes?” he asked. “For a start, we could promote freedom of expression in Afghanistan. Not that long ago we were signing Internet petitions protesting against the treatment of women by the inhumane Taliban regime and begging the Taliban not to dynamite the colossal Buddhas of Bamiyan. Now I ask you to help me identify and approach Afghani writers who would be willing to found a PEN Center in Afghanistan and to try and find ways of giving this fledgling Center the means to thrive.”

[With the help of Norwegian PEN and others, an Afghan PEN Center was in fact founded with men and women writers from all ethnic groups and was voted into PEN at the 69th Congress the following year in Mexico. Writers in Prison Committee Chair Eugene Schoulgin played an instrumental role in working with and facilitating support for the Afghan writers.]

At the Macedonia Congress Eugene reported, “In my speech in London last November I mentioned the threats to the freedom of expression I feared that would follow the events of 9/11 in the US. What has happened last year has unfortunately proved these fears were well founded. Today over 40 countries have imposed new legislation on their populations which clearly weaken their human rights. New Anti-terror laws have been established in Canada, USA, UK, France, EU as a whole, Jordan, India and New Zealand. Terrorism laws expanded on Cuba and on Italy and in Colombia, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Israel, Russia, Uzbekistan, China and in the Philippines, and terror laws have been used as an excuse to crack down on the opposition and on minorities inside their regions. This in combination with the threats of a new war on Iraq makes the present situation extremely worrying, and will most certainly give us in the WiPC reason to be even more vigilant in the year to come.”

Visiting the WiPC Committee at the Congress were two former PEN main cases—Eşber Yağmurdereli, Turkish poet/dramatist and lawyer, who was blind and spent 14 years in prison and whom a number of us had met in Istanbul at a Freedom of Expression Initiative a few years before and Flora Brovina, a Kosovair/Albanian poet and doctor who had been abducted by Serbian troops and imprisoned in Belgrade during the NATO bombing. Flora’s son had contacted PEN which sent out an urgent appeal about her abduction. I had met her husband and family when I visited Pristina, Kosovo the year before with the International Crisis Group while she was still in prison. This was the first time I met Flora, who had become an internationally celebrated case and was a member the country’s Assembly. She told the Writers in Prison Committee that every letter sent to the prison by PEN served as another attempt to tear down the walls of the prison.

Esber Yagmurdereli said at present there were around 10,000 prisoners accused of being “terrorists,” but 90% of these should be considered prisoners of conscience, and many were simply students. “On 19 December 2000, the 20th day of the protest, I was playing chess with my friend in my cell,” he said. “He was a university student named Irfan. He was my son’s age–21 or 23 years old. He defeated me three tims. He said you are 60 years old. There are so many of us whose cases ar not covered in the press, but you do get attention. We need you as much as you need us. Then came the teargas. The protests took three yours. I myself lost consciousness and came to about an hour later. I learned that 32 people had been killed–burned to death. I learned that my friend Irfan was one of them.”

Russian journalist Anna Politkovskya also attended the Macedonian Congress. She told the WIPC meeting that she got threats from criminals, military and government. “I could stay in Vienna or elsewhere in the West, but it is my decision to be in Russia because I understand more than other people that if I couldn’t write articles or give radio talks, there would be no information about Chechnya,” she said. “Because travel to Chechnya is illegal, I need to prepare my trips as if I were a spy. I have to be strong, as far as I can. My children are in Moscow, and they are also threatened. ” My last meeting with Anna was sharing thick coffee at a tiny airport café in Skopje on our way home from the Congress.

Resolution for change in wording of PEN’s Charter; amended wording, noted and approved, proposed by English PEN president Victoria Glendinning. Final proposal and approval to take place at Mexico Congress in 2003.

In addition to its traditional work, International PEN was proceeding with modernizing its governance and structure, led by International Secretary Terry Carlbom and the Board of PEN. Deputy Vice Chair of the Board Carles Torner reported that this included the restructuring of PEN and the PEN Foundation as British charitable tax law was changing; also new roles for the Vice Presidents were being considered; a modest change in the Charter was proposed for this Assembly to be confirmed at the next year’s Congress in Mexico, and the Treasurer was proposing a new international dues structure with a graded system, raising dues for centers from wealthier economies and reducing dues for others, based on the World Bank system of four categories. The change in the dues structure was unanimously approved.

Elections at the Congress included two new Vice Presidents Lucina Kathmann (San Miguel Allende PEN) and Boris Novak (Slovene PEN) and new Board members Takeaki Hori (Japan PEN), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN) and Elisabeth Nordgren (Finnish PEN).

“We are at the end of the first mandate of the first Board elected three years ago during the Warsaw Congress under the new Regulations.” Carles reported. “…we now have a real capacity for collective decision-making between Congresses…we are noticing that the transformation we dreamed of six years ago, when the new structuring of International PEN started, has taken place. There are more people involved in the work of International PEN, and each person represents a specific sensitivity within our international community…and we are better prepared to achieve our task now and in the future.”

The modernization and reform of governance also applied to PEN’s more than 130 centers with agreement that new centers from unrepresented parts of the world needed to be developed and centers that no longer functioned or worked in harmony with PEN’s Charter should be disbanded though there was often reluctance among PEN members to close a center.

At the Macedonia Congress, a particular PEN-like debate arose over the Langue d’Oc Center which no longer functioned. Langue d’Oc, or the Language of the Troubadours, was still spoken in a region in the South of France, in part of Italy and in one valley in Spain. The center’s president, whose name was the same as a great literary character, had worked on PEN’s Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights with PEN’s Committee on Translation and Linguistic Rights half a dozen years before, and one member was still eager to keep the center going as a cause of minority languages. But the elderly outgoing President was not able to help, according to Jane Spender, PEN’s Administrative Director, who communicated or tried to communicate, with these centers. The center no longer functioned, had no office or contacts who replied, she reported. Before the center was declared closed, however, former International Secretary Alexander Blokh proposed that it be declared dormant and during the ensuing year French PEN writers who knew some of the members would “try to wake them up.” The Portuguese PEN delegate also offered to help as did the Esperanto, Slovene and Galician delegates. A similar lifeline was given to the inactive Welsh center by English PEN who agreed to perform the same role.

At PEN’s Congress the following year in Mexico, the interventions confirmed that after a year of dormancy neither center had rallied and so the Assembly voted to close the centers. In both cases new writers then came forward, and a few years later a new and active Welsh Center and Langue d’Oc Center formed and were elected back into PEN’s Assembly.

At the Macedonia Congress three brand new centers—Kyrghyz, Sierra Leone, and Tibet—joined the PEN family. It was in this fashion that PEN International pruned, renewed and broadened its base in civil society among nations and cultures and languages.

Lake Ohrid in the hills of North Macedonia between Macedonia and eastern Albania

Next Installment: PEN Journey 27: San Miguel Allende and Other Destinations–PEN’s Work Between Congresses