Posts Tagged ‘Trieste PEN’

PEN Journey 29: Mexico City and the Road Ahead—Part I, Form

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

A PEN International World Congress is a hybrid—a mini-UN General Assembly with delegates sitting at tables behind their center’s (and often country’s) name plates discussing world affairs that relate to writers; an academic conference with panelists addressing abstract philosophical themes; a literary festival with writers reading their poetry and stories and sharing books, and finally a civic engagement with resolutions passed on global issues which are then delivered, sometimes by a march or candlelight vigil to a country’s embassy that is oppressing writers.

Heads of state and UN officials frequently visit and/or speak at PEN Congresses depending on the openness of the host country; esteemed writers, including Nobel laureates, and former PEN main cases are often guests. The Congress’ size varies depending on the resources available, but the financial commitment is out of reach for many PEN Centers.

PEN International 69th Congress 2003. L to R: PEN main case General José Francisco Gallardo and family; Homero Aridjis, PEN International President; Terry Carlbom, PEN International Secretary; Nadine Gordimer, PEN International Vice President. (photo courtesy of Sara Whyatt)

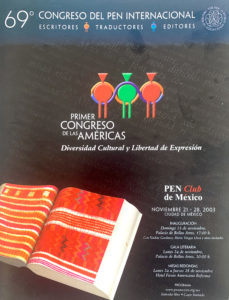

The 2003 International PEN Congress in Mexico City was celebrated as the First Congress of the Americas. Hosted by Mexican PEN, it was also supported by Canadian PEN, Quebecois PEN, American PEN, and the Latin American PEN Foundation. It was the final Congress under the presidency of Mexican poet and novelist Homero Aridjis. Organized around the theme of “Cultural Diversity and Freedom of Expression,” the 69th Congress welcomed delegates from 72 PEN Centers from every continent except Antarctica. At the Assembly six new centers were admitted—Afghanistan, Morocco, Paraguay, Spain, Trieste, and Zambia; three dormant centers—Chilean, Kenyan and German-speaking Writers Abroad—were reinstated as active.

PEN International First Congress of the Americas 2003 in Mexico City. Theme: Cultural Diversity and Freedom of Expression

The admission of new centers was especially celebratory because of the number and the variety, leading with Afghanistan. Two delegates—a man and a woman—had traveled from Kabul in spite of the conflict in the country. Eugene Schoulgin, chair of the Writers in Prison Committee and member of Norwegian PEN, had visited Afghanistan twice that year along with Norwegian PEN member Elisabeth Eide. Eugene told the Assembly how impressed they were by the courage and vitality of the Afghan writers. “For them, after so many years of war, it was extremely important to open a window to the world through which they could look outwards and through which others could be introduced to their rich literature and culture and become friends in this tormented part of the world.”

Twenty Afghan writers had rented space in Kabul for a writers house, signed the PEN Charter and sent it to London with their membership application. (Less than a decade later there were 1000 members of Afghan PEN.) The Afghan delegate Partaw Naderi told the Assembly in order to reflect the major languages and communities in Afghanistan, the center planned to have a Pashtun language section, a Persian language section, and a section for Uzbek, Turkmen and other local people. In the last three decades writers had become refugees, mainly in Pakistan and Iran and some in the West, he said. Now one of the cultural centers in Kabul was ready to publish work by some of them though “freedom of expression was very, very limited” with frequent attacks and killings of writers and journalists. He had made the long trip to attend PEN’s Congress in order “to be among kind people,” and he profoundly wished for democracy and freedom of speech in Afghanistan.

Alexander Tkachenko of Russian PEN and a PEN International Board member observed that the Soviet Union had brought great trouble for 20 years to the Afghan people, their culture and literature, and he apologized for this and gave support to the new PEN center.

In response, Safia Siddiqi, the second Afghan delegate, said writers were not enemies; it was the governments. “Pens did not kill people, pens constructed things and helped people to join together in friendship,” she said, urging “their brother from Russia,” not to feel that writers were ever the enemy of each other. Thanking all who had made this trip possible, she noted it was also important that women participate and overcome restrictions and cross boundaries to come to places like Mexico.

Every new PEN center has its own story and mandate. I expand here on only one more at the Mexican Congress because that center’s raison d’etre also represented a change that was about to be voted on regarding PEN’s Charter.

The Trieste Center’s organizing principle was not nationality—it was located in Northern Italy—nor a single language—the writers spoke and wrote in Italian and many other languages—but culture as an organizing principle. The majority of PEN Centers were formed around geographic and national locations such as the new Morocco, Paraguay and Zambian centers. Countries can have as many as five centers if the nation is large like Russia, China and the U.S. or if there are multiple languages originating within its borders such as Spain which now had three centers—Catalan, Galician and Spanish centers or like Switzerland which had four centers—Swiss Romand, Swiss German, Swiss Italian-Reto-Romanish, and Esperanto. A few centers were formed in exile when the host country was not free enough for a PEN Center like Vietnamese Writers Abroad or Cuban Writers in Exile centers.

The Trieste Center was unusual. Endorsing the new center, Giorgio Silfer of Esperanto PEN observed that PEN centers did not represent nations; they represented literature, and literature did not need a nation to give it identity—as was the case with Yiddish, Roma and Esperanto. Literature established its own territory, and when a language was dead, its literature was simply and only an expression of connection with memory, he said. Trieste was a unique place, a cosmopolitan city: its writers in Italian were the expression of a culture that was not exactly Italian culture, but which incorporated expressions from other linguistic traditions.

Tone Persak of Slovene PEN added that Trieste had been “the town in the open space, on the open wind.” There had been extraordinary writers in different languages there: Italian, Slovene, English, Spanish, Croatian, Serbian, Yiddish, German, Friulian and so on. James Joyce, Rainer Maria Rilke, Italo Svevo, Juan Octavio Prenz. It had been a town of many conflicts but also the town of the cohabitation of different cultures.

PEN International’s Charter before amendments in earlier brochure

Serbian delegate Vida Ognjenović and Croatian delegate and PEN International Board member Sibila Petlevski highlighted the multilingualism in Trieste and observed that the current situation after many, many Balkan wars had created an environment in Trieste where a PEN Center whose members came from different nations could cooperate with the Italian Center and all the other Centers in the region and give rise to new ideas. The Trieste Center was accepted.

The following day an amendment to PEN’s Charter was approved, the first change to this central document since the Charter’s text was agreed at the 1948 Copenhagen Congress. Literature’s origin beyond nationality informed the amendment which had been presented at the 2002 Macedonian Congress and vetted over the past year. The revision was a simple deletion of words. The Charter’s first item would now read: “Literature [deleted “national though it be in origin”] knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.”

At the Mexico Congress another amendment was proposed and discussed for the fourth item in the Charter and would have a year for further consultation. The vote would come at the 2004 Congress. Both amendments involved a fine-tuning of words, reflected in the many pages of minutes, and an attention and passion for language and the translation of language which only a gathering of writers would have patience for.

These amendments and the changes proposed for the Regulations that evolved in the strategic planning process were shepherded by the International Secretary Terry Carlbom and especially by the Administrative Director Jane Spender whose patience and humor and intelligence kept everyone on track. The laborious task of taking more than 130 delegates through 30 Articles, often with subsets, fell to PEN International Board Member Eric Lax whose Sisyphean patience and care led the Assembly item by item. Ultimately all the recommended changes to the governance and structure of International PEN were approved.

The highlights involved the role and authority of the International PEN Foundation which focused on gathering resources for PEN and whose trustees had a voice on the Board but were also governed by the Board; the roles and authority of the International Secretary, the President and Board. The International President was to be a “distinguished writer of international literary reputation,” and the International Secretary was to have “actively participated in the affairs of International PEN” and was given a vote on the Board. These relationships were a moving target and would remain so over the years to come. In 2003 the President was given the discretion to lead and chair the Board and the Assembly but not the obligation so the role would depend on who occupied the office. A more formal Search Committee was established to seek out candidates for the positions of President, International Secretary and Board and to be elected by the Assembly on nomination by the Board. Chairs of both standing and special committees could attend regular board meetings but had no vote.

Deputy Chair of the Board Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN) reported to the Assembly that the first Aim of the Strategic Plan, “Building the community of writers” included the item “expand PEN’s presence around the world and, in doing so, develop its humanitarian and cultural mission.” PEN was now pursuing a policy of cooperation with other organizations, initiated by the International Secretary’s signing of a cooperation agreement between International PEN and the European-Pacific Congress Alliance. The full Strategic Planning document would continue through a consultative process with the centers and be on the agenda for approval at the 2004 Congress in Tromso, Norway.

Parsing through, revising, getting approval of strategic plans and regulations for an organization as complex and diverse as PEN was a tedious but necessary task and reminded me of the book title “The Anarchists’ Convention.” Though rules and regulations and strategic plans would change in the years ahead, the Mexico Congress document was a base from which PEN grew and shape-shifted. Those who sat in the large Fiesta Americana ballroom can perhaps still hear Eric’s patient voice: “And now turn to Article 23…Comments…There being no further discussion, Article 23 is approved. Now turn to Article 24…”

Next Installment: PEN Journey 29: Mexico City and the Road Ahead—Part II, Substance