Posts Tagged ‘Alexander Tkachenko’

PEN Journey 40: The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

At the end of September 2005 a Danish newspaper published 12 editorial cartoons which depicted Mohammed in various poses as part of a debate over criticism of Islam and self-censorship. Muslim groups in Denmark objected, and by early 2006 protests, violent demonstrations and even riots erupted in Muslim areas around the world. The offense was the “blasphemy” of drawing Mohammed in the first place and the particular mockery of some of the depictions in the cartoons.

The uproar over the Jyllands-Posten Mohammed cartoons quickly drew PEN into the controversy, first through Danish PEN and then through the International PEN office and other PEN Centers. PEN included many Muslim members and numbers of centers in majority Muslim countries. All PEN members and centers endorse the ideals stated in the PEN Charter. However, the third and fourth articles of the Charter which addressed the situation, also at times appeared to contradict each other:

Article 3: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

Article 4: “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world toward a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restrain, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

PEN International Board and Staff 2006. L to R: Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Elizabeth Nordgren (Finish PEN), Jane Spender (Programs Director) Sara Whyatt (Writers in Prison Committee Director), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Karen Efford (Programs Officer), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International President), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Britta Junge-Pederson (Treasurer), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair), Chip Rolley (Search Committee Chair), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Peter Firkin (Centers Coordinator) [not pictured: Mohammed Magani (Algerian PEN), Karin Clark (WiPC Chair), Kata Kulavkova ( Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair)

Peace Committee program 2006. Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Veno Taufer (Peace Committee Chair)

At the Peace Committee conference that April, I observed, “The Charter of PEN asserts values that can appear contradictory, but represent the dialectic upon which free societies operate and tolerate competing ideas…In our 85th year, International PEN still represents that longing for a world in which people communicate and respect differences, share culture and literature, and battle ideas but not each other.”

The Danish cartoon controversy led off 2006. For me, the PEN year also included attending the conferences of three of PEN’s four standing committees—the Peace Committee in Bled, Slovenia, Writers in Prison Committee in Istanbul, Turkey (PEN Journey 35) and Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee in Ohrid, Macedonia (PEN Journey 39)—and in May the 72nd PEN World Congress in Berlin, and later a Danish Conference on the Middle East in Copenhagen, the Gothenburg Book Fair in Sweden, a PAN Africa Conference in Dakar, Senegal and a trip to Moscow, where I went to watch my oldest son compete in the European Wrestling Championships and visited Russian PEN on a mission.

Russian PEN members meeting in Russian PEN office, including Alexander Tkachenko, General Secretary, 2006

To Moscow I took just under $10,000 raised by PEN centers and buried in my luggage to help the Russian PEN Center. Vladimir Putin and the Russian government had begun to crackdown on nongovernmental organizations with ties to other countries. One of their first targets was Russian PEN which had opposed the legislation restricting nongovernmental organizations. At the time I was also on the board of Human Rights Watch, a larger organization which was watching closely what was happening to PEN. The government’s attack on Russian PEN came in the form of a freeze on all assets for failure to pay a land tax. Russian PEN argued that it was a legal tenant where it had been conducting business and was not liable for the tax on the land, but the tax office refused to drop the charges. The government threatened to close PEN and take away its office if the money wasn’t paid. An appeal had gone out to PEN’s other centers, which had responded from around the globe not only with protests to Moscow but also with funds for Russian PEN.

I brought in funds just under the amount I would have had to declare. During the wrestling tournament I met with Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko, the General Secretary of Russian PEN, and delivered to him the donation, and he gave me a receipt. The funds stayed off the crisis for then. Charges were dropped. A Russian Minister said, “I don’t understand. I was getting letters from as far away as Argentina!” Sascha answered him: “That is the kind of organization we are.” PEN continued to operate.

In Moscow I also met with Russian PEN members as well as with Turkmen author Rakhim Esenov, who was visiting Russian PEN. I had met Esenov a few weeks before in New York where he had won PEN America’s Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write award. In Turkmenistan Esenov had been charged with “inciting social, national and religious hatred using the mass media” because of characters in his novel The Crowned Wanderer. Set in the 16th century Mogul Empire, the story focused on a poet/philosopher/army general who was said to have saved Turkmenistan from fragmentation. The president of Turkmenistan Saparmurad Niyazov banned the book for portraying the main character as a Shia rather than a Sunni Muslim, and he imprisoned Esenov for several months. I still have the massive Russian language volume he shared with me, a work that had taken him years to write.

L to R: Russian PEN General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko and Russian PEN member outside Russian PEN office in Moscow and Rakhim Esenov, author of The Crowned Wander and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), 2006

At the Peace Committee conference earlier that month I’d presented a paper on the conference theme “The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World,” a broad and challenging topic which had inspired me to peer both backward and forward.

Below is the beginning of that paper with a link to the rest:

My first memory of a PEN meeting was sitting in someone’s living room in Los Angles writing postcards to free Wei Jingsheng from prison in China. At the time in the 1980’s he’d already been in prison several years of a fifteen-year sentence. I had no idea who this writer was thousands of miles away. I barely knew the other writers in that living room. On the coffee table would have been PEN’s Case List, which at the time was white sheets of paper stapled together.

We wrote and stamped our post cards for Wei and other writers that afternoon. I’m sure we were provided with background on his case. I pictured these cards fluttering into a jail somewhere in China and perhaps even into the cell of this stranger to let him know we had taken note of him and cared what happened. Looking back on the blue-sky afternoon as we sipped sodas and ate crackers and cheese, I see our act as a bit fleeting, an effort to imagine the fate of another writer who didn’t have our freedom to write and speak…[continue reading here]

Next Installment: PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN Journey 29: Mexico City and the Road Ahead—Part I, Form

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

A PEN International World Congress is a hybrid—a mini-UN General Assembly with delegates sitting at tables behind their center’s (and often country’s) name plates discussing world affairs that relate to writers; an academic conference with panelists addressing abstract philosophical themes; a literary festival with writers reading their poetry and stories and sharing books, and finally a civic engagement with resolutions passed on global issues which are then delivered, sometimes by a march or candlelight vigil to a country’s embassy that is oppressing writers.

Heads of state and UN officials frequently visit and/or speak at PEN Congresses depending on the openness of the host country; esteemed writers, including Nobel laureates, and former PEN main cases are often guests. The Congress’ size varies depending on the resources available, but the financial commitment is out of reach for many PEN Centers.

PEN International 69th Congress 2003. L to R: PEN main case General José Francisco Gallardo and family; Homero Aridjis, PEN International President; Terry Carlbom, PEN International Secretary; Nadine Gordimer, PEN International Vice President. (photo courtesy of Sara Whyatt)

The 2003 International PEN Congress in Mexico City was celebrated as the First Congress of the Americas. Hosted by Mexican PEN, it was also supported by Canadian PEN, Quebecois PEN, American PEN, and the Latin American PEN Foundation. It was the final Congress under the presidency of Mexican poet and novelist Homero Aridjis. Organized around the theme of “Cultural Diversity and Freedom of Expression,” the 69th Congress welcomed delegates from 72 PEN Centers from every continent except Antarctica. At the Assembly six new centers were admitted—Afghanistan, Morocco, Paraguay, Spain, Trieste, and Zambia; three dormant centers—Chilean, Kenyan and German-speaking Writers Abroad—were reinstated as active.

PEN International First Congress of the Americas 2003 in Mexico City. Theme: Cultural Diversity and Freedom of Expression

The admission of new centers was especially celebratory because of the number and the variety, leading with Afghanistan. Two delegates—a man and a woman—had traveled from Kabul in spite of the conflict in the country. Eugene Schoulgin, chair of the Writers in Prison Committee and member of Norwegian PEN, had visited Afghanistan twice that year along with Norwegian PEN member Elisabeth Eide. Eugene told the Assembly how impressed they were by the courage and vitality of the Afghan writers. “For them, after so many years of war, it was extremely important to open a window to the world through which they could look outwards and through which others could be introduced to their rich literature and culture and become friends in this tormented part of the world.”

Twenty Afghan writers had rented space in Kabul for a writers house, signed the PEN Charter and sent it to London with their membership application. (Less than a decade later there were 1000 members of Afghan PEN.) The Afghan delegate Partaw Naderi told the Assembly in order to reflect the major languages and communities in Afghanistan, the center planned to have a Pashtun language section, a Persian language section, and a section for Uzbek, Turkmen and other local people. In the last three decades writers had become refugees, mainly in Pakistan and Iran and some in the West, he said. Now one of the cultural centers in Kabul was ready to publish work by some of them though “freedom of expression was very, very limited” with frequent attacks and killings of writers and journalists. He had made the long trip to attend PEN’s Congress in order “to be among kind people,” and he profoundly wished for democracy and freedom of speech in Afghanistan.

Alexander Tkachenko of Russian PEN and a PEN International Board member observed that the Soviet Union had brought great trouble for 20 years to the Afghan people, their culture and literature, and he apologized for this and gave support to the new PEN center.

In response, Safia Siddiqi, the second Afghan delegate, said writers were not enemies; it was the governments. “Pens did not kill people, pens constructed things and helped people to join together in friendship,” she said, urging “their brother from Russia,” not to feel that writers were ever the enemy of each other. Thanking all who had made this trip possible, she noted it was also important that women participate and overcome restrictions and cross boundaries to come to places like Mexico.

Every new PEN center has its own story and mandate. I expand here on only one more at the Mexican Congress because that center’s raison d’etre also represented a change that was about to be voted on regarding PEN’s Charter.

The Trieste Center’s organizing principle was not nationality—it was located in Northern Italy—nor a single language—the writers spoke and wrote in Italian and many other languages—but culture as an organizing principle. The majority of PEN Centers were formed around geographic and national locations such as the new Morocco, Paraguay and Zambian centers. Countries can have as many as five centers if the nation is large like Russia, China and the U.S. or if there are multiple languages originating within its borders such as Spain which now had three centers—Catalan, Galician and Spanish centers or like Switzerland which had four centers—Swiss Romand, Swiss German, Swiss Italian-Reto-Romanish, and Esperanto. A few centers were formed in exile when the host country was not free enough for a PEN Center like Vietnamese Writers Abroad or Cuban Writers in Exile centers.

The Trieste Center was unusual. Endorsing the new center, Giorgio Silfer of Esperanto PEN observed that PEN centers did not represent nations; they represented literature, and literature did not need a nation to give it identity—as was the case with Yiddish, Roma and Esperanto. Literature established its own territory, and when a language was dead, its literature was simply and only an expression of connection with memory, he said. Trieste was a unique place, a cosmopolitan city: its writers in Italian were the expression of a culture that was not exactly Italian culture, but which incorporated expressions from other linguistic traditions.

Tone Persak of Slovene PEN added that Trieste had been “the town in the open space, on the open wind.” There had been extraordinary writers in different languages there: Italian, Slovene, English, Spanish, Croatian, Serbian, Yiddish, German, Friulian and so on. James Joyce, Rainer Maria Rilke, Italo Svevo, Juan Octavio Prenz. It had been a town of many conflicts but also the town of the cohabitation of different cultures.

PEN International’s Charter before amendments in earlier brochure

Serbian delegate Vida Ognjenović and Croatian delegate and PEN International Board member Sibila Petlevski highlighted the multilingualism in Trieste and observed that the current situation after many, many Balkan wars had created an environment in Trieste where a PEN Center whose members came from different nations could cooperate with the Italian Center and all the other Centers in the region and give rise to new ideas. The Trieste Center was accepted.

The following day an amendment to PEN’s Charter was approved, the first change to this central document since the Charter’s text was agreed at the 1948 Copenhagen Congress. Literature’s origin beyond nationality informed the amendment which had been presented at the 2002 Macedonian Congress and vetted over the past year. The revision was a simple deletion of words. The Charter’s first item would now read: “Literature [deleted “national though it be in origin”] knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.”

At the Mexico Congress another amendment was proposed and discussed for the fourth item in the Charter and would have a year for further consultation. The vote would come at the 2004 Congress. Both amendments involved a fine-tuning of words, reflected in the many pages of minutes, and an attention and passion for language and the translation of language which only a gathering of writers would have patience for.

These amendments and the changes proposed for the Regulations that evolved in the strategic planning process were shepherded by the International Secretary Terry Carlbom and especially by the Administrative Director Jane Spender whose patience and humor and intelligence kept everyone on track. The laborious task of taking more than 130 delegates through 30 Articles, often with subsets, fell to PEN International Board Member Eric Lax whose Sisyphean patience and care led the Assembly item by item. Ultimately all the recommended changes to the governance and structure of International PEN were approved.

The highlights involved the role and authority of the International PEN Foundation which focused on gathering resources for PEN and whose trustees had a voice on the Board but were also governed by the Board; the roles and authority of the International Secretary, the President and Board. The International President was to be a “distinguished writer of international literary reputation,” and the International Secretary was to have “actively participated in the affairs of International PEN” and was given a vote on the Board. These relationships were a moving target and would remain so over the years to come. In 2003 the President was given the discretion to lead and chair the Board and the Assembly but not the obligation so the role would depend on who occupied the office. A more formal Search Committee was established to seek out candidates for the positions of President, International Secretary and Board and to be elected by the Assembly on nomination by the Board. Chairs of both standing and special committees could attend regular board meetings but had no vote.

Deputy Chair of the Board Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN) reported to the Assembly that the first Aim of the Strategic Plan, “Building the community of writers” included the item “expand PEN’s presence around the world and, in doing so, develop its humanitarian and cultural mission.” PEN was now pursuing a policy of cooperation with other organizations, initiated by the International Secretary’s signing of a cooperation agreement between International PEN and the European-Pacific Congress Alliance. The full Strategic Planning document would continue through a consultative process with the centers and be on the agenda for approval at the 2004 Congress in Tromso, Norway.

Parsing through, revising, getting approval of strategic plans and regulations for an organization as complex and diverse as PEN was a tedious but necessary task and reminded me of the book title “The Anarchists’ Convention.” Though rules and regulations and strategic plans would change in the years ahead, the Mexico Congress document was a base from which PEN grew and shape-shifted. Those who sat in the large Fiesta Americana ballroom can perhaps still hear Eric’s patient voice: “And now turn to Article 23…Comments…There being no further discussion, Article 23 is approved. Now turn to Article 24…”

Next Installment: PEN Journey 29: Mexico City and the Road Ahead—Part II, Substance

PEN Journey 24: Moscow—Face Off/Face Down: Blinis and Bombs—Welcome to the 21st Century

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

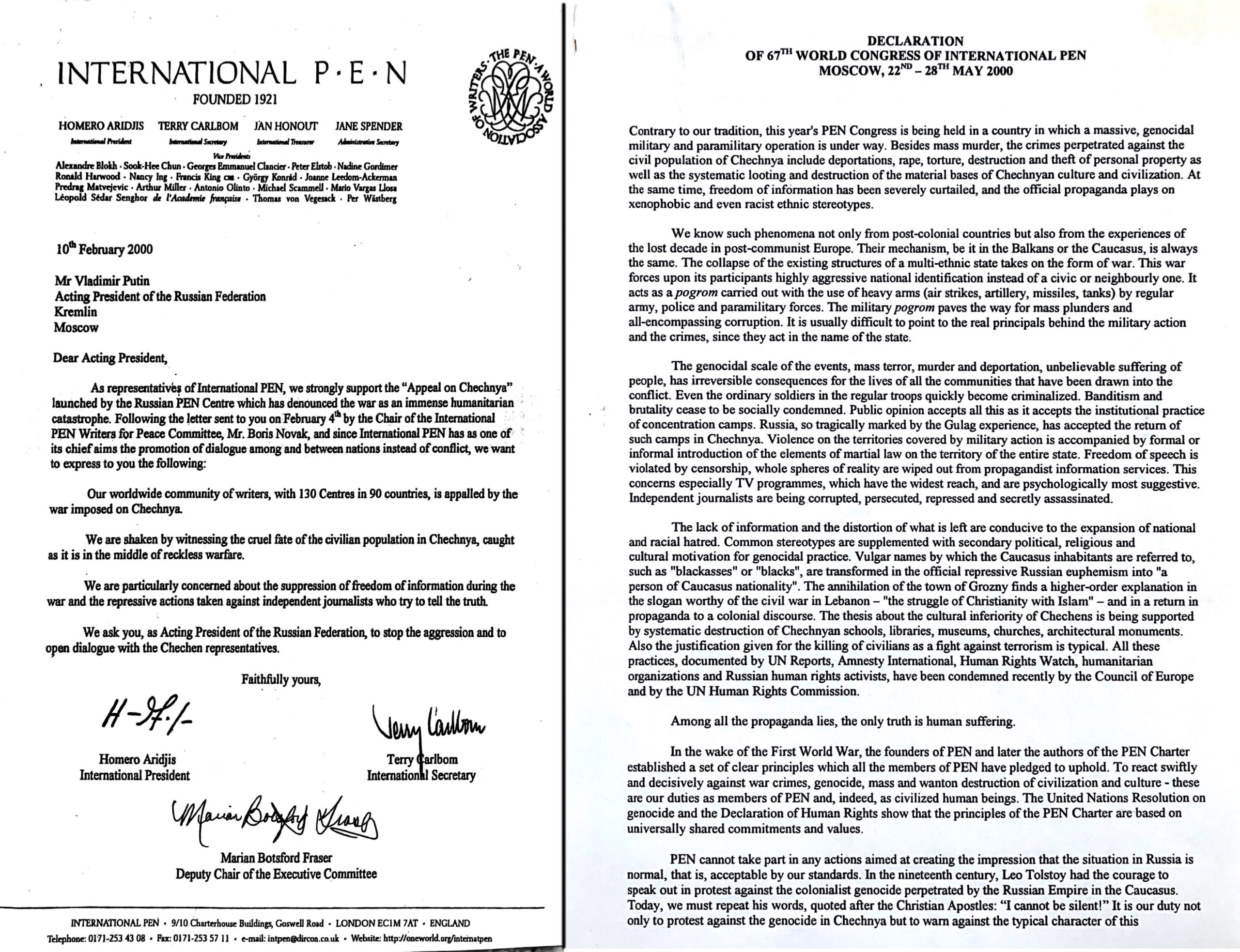

“Contrary to our tradition, this year’s PEN Congress is being held in a country in which a massive, genocidal military and paramilitary operation is under way. Besides mass murder, the crimes perpetrated against the civil population of Chechnya include deportation, rape, torture, destruction and theft of personal property as well as the systematic looting and destruction of the material bases of Chechnyan culture and civilization. At the same time, freedom of information has been severely curtailed, and the official propaganda plays on xenophobic and even racist ethnic stereotypes…” So began a Declaration from the 67th World Congress of International PEN voted by the Assembly of Delegates in May, 2000.

Program for PEN International 67th World Congress, Moscow

The decision to hold the International PEN Congress in Moscow was a controversial one, resulting in some members refusing to attend because of Russia’s prosecution of the war in Chechnya and the concern that holding a Congress in Moscow would give the government an appearance of approval. However, PEN’s Secretariat with the new Executive Committee concluded that the long-planned millennial Congress also presented the opportunity for International PEN to show solidarity with Russian PEN which had been outspoken both on the war and on behalf of Russian journalists and writers under pressure.

“The writers of Russia, united under the auspices of the Russian Centre of the International PEN Club, are concerned about the escalation of the war in Chechnya which is becoming a threat to not only peaceful residents of Grozny-city but also to the national security of Russia. The ultimatum announced to women, children and old people of the Chechen capital makes them hostages of both terrorists and federal forces. It is hard to believe that in this situation the Russian authorities are going to use the same methods as terrorists. We are very aware how hard it is to cut the tight Chechen knot, but in any case innocent people do not have to become victims of the decisions taken…” Russian PEN sent this appeal earlier to the acting President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin.

Russian PEN members, including President Andrei Bitov, had signed the appeal. Russian PEN’s General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko noted at the Congress that it was essential to call on all those involved—Russian and Chechen—to cease their brutalities. Sascha himself had regularly stood up to the Russian government. He championed the cases of imprisoned writers Alexandr Nikitin and Grigory Pasko, both of whom had recently been freed after trials. Pasko, who was a journalist and former Russian Naval officer, had been arrested and accused of espionage for his publication of environmental problems in the Sea of Japan. Nikitin, a Naval officer, had been charged with stealing state secrets by contributing to a report that revealed the sinking of Russian nuclear submarines and the dangers these decaying submarines posed to the environment.

German novelist Günter Grass talk opened PEN’s 67th Congress

The freedom and the openings which many embraced after the break-up of the Soviet Union in the early 1990’s were beginning to close down and restrictions tighten. At the Moscow Congress Pasko expressed his gratitude for everything PEN had done to obtain his freedom. He urged the Assembly to focus on environmental problems. But he warned that the structure of the current Russian government had grown out of the KGB, and he feared nothing good would come for free speech or the environment.

In the opening address of the Congress German novelist Günter Grass, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature the previous year, recounted the many times in the past century that writers had called attention to the abuses and genocides which governments had tried to hide. “At least literature does achieve this—it does not turn a blind eye; it does not forget; it does break the silence,” Grass concluded.

The Congress theme “Freedom of Criticism. Criticism of Freedom…”seemed a particularly UNESCO title, with a focus on how freedom is exercised, noting that freedom unrestrained by morality can lead to a license for corruption, brigandage, state terrorism, censorship and the wanton murder of those who dare to speak out. “That freedom is a double-edged sword is a fact long appreciated in free societies. It is what prompted Voltaire to place a limitation upon it, when it interfered with the freedom of another,” one Congress description noted.

Thus framed, the panels and the work of PEN’s committees proceeded. Many wondered how able PEN members would be to criticize openly as we met both formally and in cafes sharing conversation and meals of blinis and caviar. There was no incident nor interference that I recall at the Moscow Congress nor at the subsequent programs in St. Petersburg, but we were all aware that repercussions could follow after we left. Over time Putin’s government did close down the space for NGO’s with Russian PEN as one of the early targets. (Future blog post.)

The Moscow Congress itself proved an opportunity to celebrate Russian literature and other literature as well as to conduct the work of PEN’s committees which met in halls named after Tolstoy, Pushkin, and Chekov. Many writers from over 70 PEN centers were visiting Moscow for the first time since the Soviet Union broke apart. Since my first trip in 1991 shortly after the coup attempt (PEN Journey 8), the city had changed. Western hotels, restaurants and stores had moved in; certain citizens had amassed wealth; others had lost jobs and security. It was a city of contrasts with children on the street begging, but begging by playing violins. A wealthy new group crowded the lobbies of western hotels and department stores.

On the streets at PEN Congress in Moscow May, 2000: L: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, PEN Vice President; R: Sara Whyatt, PEN Writers in Prison Committee Program Director

In a message to the Congress Andrei Bitov wrote:

Full text of Russian PEN President Andrei Bitov’s message to PEN delegates

I always believed…that I would meet my old age in the USSR under Brezhnev, much though I disliked the idea. I could not allow myself to dream (or I would have been driven to despair) that I would be lucky enough to travel around the world more or less without restriction, that my works would be published without being censored, published with no delay and in their entirety, however hastily written.

Under Brezhnev one could not think of joining the PEN Club—that “reactionary bourgeois, anti-Soviet, etc., organization”! (It turned out only recently that Gorky, Pilniak and Voinovich had all dreamt of such a grouping…)

One could certainly never have imagined its World Congress being held in Moscow!

But fifteen years have elapsed since that time, long enough to see many people grow old and die and another generation come into the world and reach their youth. That is the History none of us, either here or in the wider world, could imagine…

We should not rail at the century that has gone, nor at the passing year—we should hope that they have taught us much. However, judging by events in Russia and in the rest of the world, it is obvious that we have not drawn any sensible conclusions from our experience…

In one tiny drop of the substance of the World Congress is reflected the entire universe, the problems it faces reflect, as in a distorting mirror, world political problems…

We are responsible for each day of our lives, not for the future.

Thank you for having the determination (and courage) to come to Russia at this particular time.

PEN’s business at the Assembly of Delegates included the International Secretary Terry Carlbom’s report on PEN’s relationship with UNESCO as the only global organization representing literature associated with UNESCO and a preliminary notice about a multi-year strategic plan under development. Business also included the election of the International President. Homero Aridjis was standing for a second term, and former International Secretary Alexander Blokh of Russian origin had returned to this PEN Congress for the first time since he’d stepped down as International Secretary in 1998, (PEN Journey 20) and he was also running for President. I was asked to chair the Assembly for the election, including during a stir that arose when Alex wasn’t present to speak for his candidature. He’d left the meeting early for an appointment, mistakenly thinking he would speak in the afternoon. However, there was no afternoon session, and controversy arose over whether the election should be postponed so he could speak. I ruled that he would be the first item on the morning agenda and then the election would proceed as scheduled. Homero Aridjis won a second term; Alexander Blokh continued to serve PEN for many years as a Vice President and President of French PEN.

Also at the Congress Martha Cerda (Guadalajara Center) succeeded Lucina Kathmann as Chair of the Women Writers’ Committee; Veno Taufer (Slovene PEN) succeeded Boris Novak, who’d opposed holding the Congress in Moscow and had stepped down as chair of the Writers for Peace Committee, and Eugene Schoulgin (Swedish PEN) was confirmed as the new Writers in Prison Committee Chair.

In his farewell comments as WiPC chair Moris Farhi quoted Günter Grass’s address that literature always breaks the silence. Moris added that by breaking the silence, by telling the truth and exposing wrong-doing, literature also defied fear and embraced courage. The members of International PEN had witnessed this defiance of fear and the manifestation of courage time and again. Moris noted among those with courage were Grigory Pasko, Alexander Tkachenko and our colleague Boris Novak.

The Moscow Congress saw the return of delegates from Chinese PEN after a decade-long absence post Tiananmen Square. Two resolutions on China were presented, one calling for the release of dissident writers imprisoned in China and another protesting the long prison terms for writers in Tibet. The Chinese delegate objected to both resolutions, arguing first that Tibet shouldn’t be singled out as though it were not part of China. He also said that the Chinese people and Chinese writers cared for human rights after centuries of feudal society, but the West emphasized individual rights and values while the Chinese valued collective human rights and obligations to the family and society. The Chinese believed that human rights in a given country were related to the social system, the level of economic development and historical and cultural traditions of that country, and they encompassed the right to development and subsistence. A country of more than 1.2 billion people had to find food and clothing. It was impossible for one pattern to solve all existing problems. The Cold War had ended, but its influence remained with those who believed their values, their concept of human rights, their position were the only correct ones in the world. Dialogue was the only way to resolve the differences of view, a dialogue based on equality and mutual respect.

Hands shot up seeking to respond. At least 25 delegates at the Assembly spoke, welcoming the return of the Chinese delegates to the PEN Congress, but most taking exception to the argument of the relativity of human rights in PEN’s work. The first to speak was Eric Lax of PEN Center USA West who said he appreciated the speaker’s comments but wanted to add that the PEN Charter, to which all members subscribed, was very clear that freedom to write was a basic tenant of the organization and that information should pass unimpeded without restriction. Some questioned the way the resolution was written. Alexander Tkachenko of Russian PEN said he felt PEN should be understanding of people living under a regime about which the rest of PEN knew little. It was up to the Assembly to decide whether to support the resolution; they needn’t accept the Chinese delegate’s opinion, but they should respect it. He didn’t want the Chinese to be missing from PEN for another ten years. PEN should be tolerant of those for whom it was extremely dangerous to discuss such questions. The Assembly applauded. A small amendment was made to the resolutions, both of which passed with large majorities, though not unanimously.

The following year the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) came into being, a center of independent writers and democracy activists inside and outside of China. One of the founding members and the second president of ICPC (2003-2007) was writer Liu Xiaobo, on whose behalf PEN worked twice when he was imprisoned after Tiananmen Square and again when he was arrested in 2009. Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010, but he was incarcerated in a Chinese jail, and he died in custody in 2017.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 25: War and more War: Retreat to London

PEN Journey 16: The Universal, the Relative and the Changing PEN

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Fremantle, Australia is far away, at least if you live in the Americas or Europe or West Africa. So is Tokyo, Manila, Nepal, Hong Kong,—all destinations of PEN Congresses and conferences. As a global organization with centers in over 100 countries, PEN tries to cover the world with its meetings and at least once or twice a decade organize a Congress in Asia or Australia with its centers there.

In 1995 for PEN International’s 62nd Congress Perth PEN hosted delegates from around the world in Fremantle, a port city on Australia’s western coast in the Perth metropolitan area, a picturesque city with Victorian architecture and, as I recall at the time, a town out of the 1960’s where time hadn’t quite caught up. The city’s reputation was partially derived from its history as a penal colony from the 1850’s to 1991. The traditional Aboriginal people who lived there called the area Walyalup “the crying place.”

In 1995 for PEN International’s 62nd Congress Perth PEN hosted delegates from around the world in Fremantle, a port city on Australia’s western coast in the Perth metropolitan area, a picturesque city with Victorian architecture and, as I recall at the time, a town out of the 1960’s where time hadn’t quite caught up. The city’s reputation was partially derived from its history as a penal colony from the 1850’s to 1991. The traditional Aboriginal people who lived there called the area Walyalup “the crying place.”

The 65th Congress was one of the smaller for PEN, less formal with many delegates staying in the homes of local writers rather than in a hotel. Instead of formal receptions in houses of state, at least one evening’s entertainment was a game of literary trivia and bingo. Because the venue was on the harbor, the swimmers among the delegates, particularly Sascha (Alexander Tkachenko) General Secretary of Russian PEN, tried to swim each day despite the warnings that waters were shark-infested. Sascha defied the sharks which he considered a milder threat than what he was dealing with back home in Russia.

The Congress theme Freedom of Expression and Cultural Context translated into an endorsement of the universality of human rights as expressed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Held in the 50th anniversary year of the United Nations’ founding, PEN insisted human rights were not a relative notion. “While the concept of a universal right may not have penetrated the mechanisms of all states, the invocation of the universal right to free expression remains one of the essential tools that PEN and other organizations use to apply pressure and insert a wedge into the conscience of nations,” the Writers in Prison Chair’s report noted that year.

While certain human rights were absolute, governance was relative, and PEN itself was beginning to struggle with its structure. The relaxed atmosphere of Fremantle allowed informal discussions among delegates who were urging a more democratic structure for PEN. As PEN International headed towards its 75th anniversary the following year, Boris Novak, Slovene PEN President and Chair of the Peace Committee noted that the inner structure of PEN was no longer adequate for the needs of such a large global organization. This sentiment was echoed by the American PEN delegate and delegates from Scandinavian centers. The International Secretary agreed to hold a special meeting in Perth on this question, and the discussion and the dissent began.

As chair of the Writers in Prison Committee, I shared the concerns, but the WiPC staff and I determined that the Writers in Prison Committee should remain a place where everyone came together and focused on the mission of getting writers out of prison and securing freedom of expression so we stayed on the edge of the debate. The internal politics of PEN were stirring and erupted a year later at the 1996 Congress in Guadalajara. In Perth, however, the breezes were balmy and the water warm enough to dip in if not to cross the distance between the old and the new. That process would evolve over the next several years and Congresses to come.

Brief summary of work follows in this excerpt from my 1995 Writers in Prison Committee Chair report:

“Since [he] was arrested, my relatives and close friends have not dared to speak to me or telephone me for fear of being arrested. They have steered clear of me. I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of friends and relatives who have stood by me. Since our problems began, I have had to rely on my family and our friends from abroad…I am very grateful to them…In short, your support will not only help my family, but also the families of others who are in distress. We will never forget your help.”

—Letter to PEN WiPC from the wife of an imprisoned writer who for reasons of security must remain anonymous.

“The work of the Writers in Prison Committee this year has included appeals on writers’ behalf to 59 countries, around 150 appeals from the London office and hundreds more from centers around the world who responded to PEN’s Rapid Action calls and to the specific cases of the prisoners they have adopted…

“The fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II saw celebrations in Europe but also saw a resurgence in racist and hate literature and speech. Anti-fascists writers found themselves threatened, especially in Austria where one writer was almost murdered. Turkey continued to be the most difficult country in the region with over 200 arrests, brief detentions, killings and disappearances, almost all relating to writings on the Kurdish situation…

“The other issues to watch—the rise of militant fundamentalism, terrorism, separatist movements—but these are generally issues over which PEN has little control even though they affect the fates of individual writers…

“Progress this year can best be measured in the releases of prisoners and also by the changes in certain countries’ laws. The Writers in Prison Committee lobbied governments and international bodies on general issues such as the death penalty, long term imprisonment and anti-terror laws and has seen some effect. PEN, along with other human rights organizations, urged the Indian government to reform or abandon its anti-terrorist law under which writers were detained, and recently the government has voted not to renew the law. The WiPC has also spent a large effort speaking with representatives of the Turkish government at embassies and at the United Nations to urge the amendment or abolishment of Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law. Just last week the Goverment finally announced its plan to amend the law. We are hopeful this will soon take place in such a way that hundreds of writers detained because of Article 8 will no longer face prison terms, though we are cautious in our optimism.

“The main substance of the Writers in Prison Committee work, however, is not shown in the statistics nor through the reformed government policy, but can best be measured in the lives of individual writers. This year over 90 writers have been released from prison and some individuals facing severe penalties, including death, have instead received clemency. Unfortunately in many countries as one writer walks out of prison, another is being brought in…

“Turkish writer Esber Yagmurdereli, who is blind, recently had his 20-month prison sentence ratified. He was arrested for a speech about the Kurdish situation at a human rights meeting just weeks after his release from 13 years in prison. [I’d like to end with] an excerpt from one of his plays, “Crossing Boundaries” which deals with the experience of a political prisoner:

The moment lost all sense of time and the door opened

You were leaving…the anguish would lift from your heart

…Your unconquered eyes would be mine from now on.

…You went and waking to your absence was to be condemned to a harsh fate

And I felt the damnation again when I heard my forehead crack against these silent walls

…Suddenly I was without a country like so many Palestinians

I even forgot my language: I forgot I was a scream in the river of your voice

(Didn’t we force these walls to memorize our voices

Didn’t we breastfeed these rotten cells our best folk songs?)

We set alight wet stones as we rested our backs against them…

…I kept biting my lips, but never forgot the memory…

And as the moon fell into the night, I saw your smile in its eternal beauty

The rainbow shone on your forehead and its greeting was a declaration

…then that moment lost all sense of time and the door opened

The silenced suddenly arose and spirits soared like rain-birds.”

Next Installment: PEN Journey 17: Gathering in Helsingør