Posts Tagged ‘International PEN Writers in Prison Committee’

PEN Journey 43: Turkey and China—One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

January 2007 began with an assassination. The Board of PEN International was just gathering in Vienna for the first meeting of the year when board member Eugene Schoulgin got a phone call letting him know that our colleague and his friend Turkish-Armenian editor Hrant Dink, had been gunned down in Istanbul and killed. Many of us had seen Hrant at the PEN Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul in March.

Editor-in-chief of the bilingual Turkish-Armenian newspaper Agos, Dink had long advocated for reconciliation between Turks and Armenians and for Turkey’s recognition of the Armenian genocide early in the century. Dink had received death threats before and had himself been prosecuted for “denigrating Turkishness,” but as with Russian colleague Anna Politkovskaya, Dink’s assassination stunned us all and set off widespread protests in Turkey and abroad. Eventually a 17-year old Turkish nationalist was arrested and convicted, but not before police were exposed posing and smiling with the killer in front of a Turkish flag.

PEN International Board Meeting, Vienna, January 2007. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary; Jiří Gruša, International President; Caroline McCormick, Executive Director; Judy Buckrich, Women Writers Committee Chair; Elizabeth Norgdren, Finish PEN; Eugene Schoulgin, Norwegian PEN; Franca Tiberto, Search Committee Chair; Sibila Petlevski, Croatian PEN; Britta Pedersen, International Treasurer; Eric Lax, PEN USA West; Mohamed Magani, Algerian PEN; Kata Kulavkova, Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair; Frank Geary, Programs; Karen Efford, Programs.

The work of PEN is, at its heart, personal. It is writers speaking up for and trying to protect other writers so that ideas can have the freedom to flow in society. In league with other human rights organizations, PEN also advocates to change systems that allow attacks and abuse. At times the work can feel ephemeral when the systems don’t change, or make progress only to regress. However, the individual writer abides, and PEN’s connection to the writer stands.

During my tenure working with PEN, Turkey and China have been the two countries that have imprisoned the most writers. For a period both nations appeared to be advancing towards more open societies but soon retreated. In the early 2000’s as Turkey aspired to join the European Union, the country operated as a democracy with a more independent judiciary; fewer writers became entangled in the judicial processes. However, in 2007 the democratic transition in Turkey began to veer off course and has continued a downward spiral towards authoritarianism ever since.

China also promised to become a more open society with the advent of the Olympic Games in 2008. Democracy activists inside and outside of China grew hopeful. In this climate, PEN held an Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in Hong Kong in February 2007; it was PEN’s first in a Chinese-speaking area of the globe. Over 130 writers from 15 countries gathered, including writers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and many of PEN’s nine Chinese-oriented centers as well as members from Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Nepal, Australia, the Philippines, Europe, and North America.

Both China’s and Turkey’s Constitutions protected freedom of expression in theory, but in practice the protection was lacking. Instead, laws and regulations prohibited content. In Turkey, exceptions included criticism of Ataturk, expressions that threatened “unitary, secular, democratic and republican nature of the state” which in effect targeted issues around Kurds and Kurdish rights. In China, the Constitution noted that “in exercising their freedoms and rights, citizens may not infringe upon the interests of the State, of society or of the collective, or upon the lawful freedom and rights of other citizens.” The state was the arbiter.

The Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 took place at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories with programs also at Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club. The theme Writers in the Chinese World celebrated Chinese literature and a dialogue among PEN’s Asian centers and also explored issues of translation, women, exile, peace, censorship, internet publishing, freedom of expression and PEN’s strategic plan.

Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories. Over 130 writers from 20 PEN centers in 15 countries gathered for the four-day conference.

However, 20 of the 35 mainland Chinese writers who planned to attend were prevented or warned off by government authorities, including the President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) Liu Xiaobo, who later won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 while imprisoned in a Chinese jail. Qin Geng had his permit rescinded and two writers—Zan Aizong and Zhao Dagong—were stopped at the border and denied permission to exit though they had permits. (Two overseas Chinese writers who attended and had other citizenship—Gui Minhai and Yang Hengjun—are now in prison in China and are PEN main cases.)

In addition, the Chinese Communist government banned eight books, including one by Zhang Yihe, an honorary board member of the ICPC who had been invited to speak at the conference but instead was warned not to attend.

China’s promised opening of its society was already contracting, and the restrictions bore a harbinger of events to come both for writers and eventually for Hong Kong. The conference attracted wide press attention with articles in Chinese and English newspapers in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and globally via the BBC and newswire services. Renowned Shanghai playwright Sha Yexin, poet Yu Kwang-chung (Yu Guangzhong) from Taiwan and Korean poet Ko Un, short-listed for the Nobel Prize for Literature, attended. But the restrictions on the mainland Chinese writers cast an ominous shadow and grabbed the largest regional and international headlines.

“PEN has nine centers representing writers in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and abroad and has great respect for Chinese Writers and Chinese literature,” International PEN President Jiří Gruša told more than 40 reporters at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, “but we are very concerned by the restrictions on writers in mainland China to write, travel and associate freely.”

In honor of the absent writers, an empty chair sat on the platform for each session of the four-day conference.

Press Conference at Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, February 2007; L to R: Translator, Journalist Gao Yu (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Jiří Gruša (PEN International President), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary)

In 2007 more than 800 writers were under threat worldwide, and at least 33 writers were in prison in China. A number of the attendees at the conference had been imprisoned and been main cases for PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), including celebrated Korean poet Ko Un and Chinese journalist Gao Yu, both of whom addressed the conference. They knew firsthand the role of the writer in the struggle for freedom, and they knew the support PEN had given, observed one of the conference organizers Yu Zhang, General Secretary of the ICPC, half of whose members lived in mainland China.

“I am no longer afraid of anything,” one Chinese writer unable to attend said in a message to the conference. “Our bodies and our spirits are our own. To speak of ugliness and injustice we have to shout, but our throats are cut when we do.”

“We are willing for some things to be burned in the soil so a new leaf will come,” added another mainland writer in a message to the conference.

“It is important that all writers get together, and all writers protect the freedom of speech and free expression. We must write what’s in our hearts and write as a witness to history,” said Qi Jiazhen, who spent 10 years in a Chinese prison and now lived in exile.

Owen H.H. Wong of Hong Kong’s English-Speaking PEN Center pointed out that Hong Kong was a meeting point of East and West, North and South, Leftists and Rightists and Modernization and Classic writing. He noted that before the 1997 handover, Hong Kong writers saw themselves as writers in exile. Only those born in Hong Kong regarded themselves as Hong Kong writers. Now most publishing houses in Hong Kong were funded by the Communist government, and free expression in Hong Kong was threatened and controlled.

Yu Jie, a Beijing-based essayist and author and vice President of ICPC, spoke at the Foreign Correspondents Club noting that even though he was able to attend the conference and speak to the foreign media, he had not been able to get published in mainland China. For mainland writers, Hong Kong was a place where freedom of expression and freedom of the press still existed, he said. “It’s as if those of us in the mainland have our heads immersed in water and cannot breathe, but Hong Kong allows us to stick our heads above the surface of the water, and for a short time, breathe freely.”

He predicted that the authorities would later “settle the score” with the writers and publishing houses. He was in fact later arrested, tortured and imprisoned for his writing. In 2012 he emigrated to the United States.

PEN International Panel at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference. L to R: Conference organizers included Yu Zhang, (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Caroline McCormick (PEN International Executive Director), Chip Rolley (Sydney PEN)

“Existing in the unofficial nooks and crannies of an emerging civil society in China, ICPC is determined to insist that their country live up to the rights guaranteed in its Constitution,” said another conference organizer, Chip Rolley, Vice President of Sydney PEN. “This continuing work will ensure that there is indeed a turning point for PEN in China and the wider Asia and Pacific region, and that this historic conference will not dissipate like smoke.”

In his keynote address Taiwanese writer and poet Yu Kwang-chung called for “all the writers and the poets across the Chinese world” to strengthen the channels of mutual exchange, and make efforts to find a consensus on basic issues such as the formation of a common national culture (which includes in particular the establishment of joint aesthetic and literary values) in order to “make a valuable contribution to preventing war and maintaining peace.”

Attendees launched a dialogue on literature as well as on networking among PEN’s Asian centers with a regional strategy for freedom of expression and translation. The conference was part of PEN International’s program to develop the regions in which PEN operated by connecting existing writers and PEN centers and also developing new centers in countries starting to open up such as Myanmar/Burma. Often a PEN center was one of the first civil-society organization to set down roots when authoritarian controls began to relax. [A Myanmar PEN Center was established in 2013.]

In a panel on Literature and Social Responsibility panelists noted that free speech and writers’ responsibilities were the basis of social prosperity and that PEN was a bridge between writers and their responsibilities.

Participants at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference from China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Philippines, Vietnam, Nepal, including speaker Yu Kwang-chung (Taiwan) seated in center.

Chen Maiping of ICPC read a message from Zhang Yihe, the mainland novelist who was to have been on the panel but who had been prevented from attending. “There is a saying: human hearts are like water, while people’s favor and loyalty feel as heavy as mountains. During these ten plus days since my books were banned, so many people have shown their concern I have nothing to give in return for their kind support other than to express my gratitude on paper. Writing is my only means of self-expression. Writers have always been prisoners of language and words. It is not an easy affair for me to live, nor can I die in peace. I can only write…In China we talk about ‘literature as a vehicle for the Tao (the Nature, the Way).’ People have talked about this for thousands of years. However, those who have written the best literature are exactly those who never think about their social responsibility. Zhang Bojun [the author’s father who was a scholar and a minister in the Chinese government in the 1950s and persecuted during the 1957 Anti-Rightist campaign in Mao’s Cultural Revolution] was an example of this. In my view his achievements were much greater than many of the contemporary writers, artists and painters. If a writer has too strong a responsibility, he may have no achievements at all.

“For several decades, literature has been tied together with ‘revolution’ and ‘reform.’ I can’t bear such responsibility. I can only recall the past. I do not have such social responsibility tied to ‘revolution‘ and ‘reform.’ I am out of date. There are so many people singing praise for the society, why not allow an old woman like me to sing a little song of my own. I am only a piece of withered leaf. I hope that I can decay quickly so that I may become a new leaf soon. “

Chen Maiping also read “Writing in Anger” by Liu Shu, another mainland writer prevented from attending. “The conflicts between our hearts and reality and an unwillingness to keep silent are the driving forces for my writing. The disgraceful politics have turned us into dissident writers. Chinese dissident writers write in isolation. The marginalized position of dissident writers has marginalized their writing. This is very different from the West. The Eastern people have the ability to suffer and digest their sufferings. This kind of ability enables writers to ignore the reality and to become numb to the suffering of their people. They choose to write only about ‘pleasant things to lighten the load on their hearts.’

“The cruelty of reality fills their lives with ‘submission.’ The writers are swollen and weighed down with humiliations and sufferings; they have lost the anger created by their reality. They have no anger at the past, nor do they imagine a future. They only write about meaningless, shallow and trivial affairs. My anger comes from my refusal to accept and make peace with this reality. I have been detained four times because of my ideas. We puzzle over social phenomena but we long for peace. The way to calm our anger is to write…I must speak for citizens who were screened by the totalitarian society, by the police and the ugly society…we do not want to be silent. Like Lu Xun said, life is ourselves: everybody is responsible for his own life. Our flesh body and our life are in exile in our homeland, until we disappear.”

Women Writers Committee gathering at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference including Chair Judy Buckrich in turquoise in center.

Women participants at the conference focused in addition on the restrictions for women writers in the region.

Qi Jiazhen was imprisoned 10 years and accused of trying to overthrow the government after she inquired whether she could study aboard. She said she had been young and inexperienced and felt guilty and wrong, the same feeling shared by other women. Gender awareness was low in China, she said. She now lives in Melbourne, Australia.

Celebrated mainland journalist Gao Yu confirmed two kinds of prisoners in China—special treatment prisoners & prisoners of conscience. As vice chief editor of an economic weekly with an international reputation, she was a special treatment prisoner. She had treatment when she was sick and had to do little hard manual work because was already 50 and given 7 years in prison. But she never admitted her wrong doing so she didn’t enjoy any pain reductions, she said.

Chinese journalist and PEN main case Gao Yu with translator.

In a panel on Censorship and Self-Censorship, Gao Yu noted that censorship began at school where children learned to protest injustice when not treated fairly. Later in life that grew into resistance of the system. The writer who sought to express truth experienced censorship which could lead to punishment and prison. But that was not as frightening as being silent, she said. The essence of being a writer was to have integrity and speak the truth.

After the conference, a dozen police picked up one participant and took him to a hotel room to find out what the conference had been about. A poet and member of ICPC, he told the police, “To build a ‘harmonious society’ and ‘harmonious culture’ [as President Hu Jintao has called for], writers should sit with writers and not always have to sit with policemen.” He was finally released after hours of interrogation.

One of the more creative campaign tools planned during the conference was spearheaded by a team of PEN Centers in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia. The members developed a digital relay with Chinese poet Shi Tao’s poem June. The poem tracked the path of the Olympic torch across a digital map. Shi Tao was serving a 10-year prison sentence for sharing with pro-democracy websites a government directive for Chinese media to downplay the 15th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests. His emails had been turned over to the Chinese government as evidence by Yahoo. His poem commemorated the Tiananmen Square massacre and was translated and read in the languages of PEN’s centers around the world, including in regional dialects as well as in the major languages. Ultimately 110 of PEN’s 145 centers participated and translated the poem into 100 languages, including Swahili, Igbo, Krio, Tsotsil, Mayan. The poem’s journey began on March 30, 2008 in Athens and traveled to every region on the online map, arriving in Hong Kong on May 2 and in June to Tibet where it was translated into Tibetan and the proposed Uyghur PEN center translated it into Uyghur. Finally August 6-8 it arrived in Beijing where it was translated and read in Mandarin. Anyone could click on the map and hear the poem in the language of the country designated.

By the 2008 Olympic Games 39 writers remained in prison in China.

June

By Shi Tao

My whole life

Will never get past ‘June’

June, when my heart died

When my poetry died

When my lover

Died in romance’s pool of blood

June, the scorching sun burns open my skin

Revealing the true nature of my wound

June, the fish swims out of the blood-red sea

Toward another place to hibernate

June, the earth shifts, the rivers fall silent

Piled up letters unable to be delivered dead.

(Translated by Chip Rolley)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 44: World Journey Beginning at Home

PEN Journey 40: The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

At the end of September 2005 a Danish newspaper published 12 editorial cartoons which depicted Mohammed in various poses as part of a debate over criticism of Islam and self-censorship. Muslim groups in Denmark objected, and by early 2006 protests, violent demonstrations and even riots erupted in Muslim areas around the world. The offense was the “blasphemy” of drawing Mohammed in the first place and the particular mockery of some of the depictions in the cartoons.

The uproar over the Jyllands-Posten Mohammed cartoons quickly drew PEN into the controversy, first through Danish PEN and then through the International PEN office and other PEN Centers. PEN included many Muslim members and numbers of centers in majority Muslim countries. All PEN members and centers endorse the ideals stated in the PEN Charter. However, the third and fourth articles of the Charter which addressed the situation, also at times appeared to contradict each other:

Article 3: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

Article 4: “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world toward a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restrain, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

PEN International Board and Staff 2006. L to R: Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Elizabeth Nordgren (Finish PEN), Jane Spender (Programs Director) Sara Whyatt (Writers in Prison Committee Director), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Karen Efford (Programs Officer), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International President), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Britta Junge-Pederson (Treasurer), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair), Chip Rolley (Search Committee Chair), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Peter Firkin (Centers Coordinator) [not pictured: Mohammed Magani (Algerian PEN), Karin Clark (WiPC Chair), Kata Kulavkova ( Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair)

Peace Committee program 2006. Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Veno Taufer (Peace Committee Chair)

At the Peace Committee conference that April, I observed, “The Charter of PEN asserts values that can appear contradictory, but represent the dialectic upon which free societies operate and tolerate competing ideas…In our 85th year, International PEN still represents that longing for a world in which people communicate and respect differences, share culture and literature, and battle ideas but not each other.”

The Danish cartoon controversy led off 2006. For me, the PEN year also included attending the conferences of three of PEN’s four standing committees—the Peace Committee in Bled, Slovenia, Writers in Prison Committee in Istanbul, Turkey (PEN Journey 35) and Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee in Ohrid, Macedonia (PEN Journey 39)—and in May the 72nd PEN World Congress in Berlin, and later a Danish Conference on the Middle East in Copenhagen, the Gothenburg Book Fair in Sweden, a PAN Africa Conference in Dakar, Senegal and a trip to Moscow, where I went to watch my oldest son compete in the European Wrestling Championships and visited Russian PEN on a mission.

Russian PEN members meeting in Russian PEN office, including Alexander Tkachenko, General Secretary, 2006

To Moscow I took just under $10,000 raised by PEN centers and buried in my luggage to help the Russian PEN Center. Vladimir Putin and the Russian government had begun to crackdown on nongovernmental organizations with ties to other countries. One of their first targets was Russian PEN which had opposed the legislation restricting nongovernmental organizations. At the time I was also on the board of Human Rights Watch, a larger organization which was watching closely what was happening to PEN. The government’s attack on Russian PEN came in the form of a freeze on all assets for failure to pay a land tax. Russian PEN argued that it was a legal tenant where it had been conducting business and was not liable for the tax on the land, but the tax office refused to drop the charges. The government threatened to close PEN and take away its office if the money wasn’t paid. An appeal had gone out to PEN’s other centers, which had responded from around the globe not only with protests to Moscow but also with funds for Russian PEN.

I brought in funds just under the amount I would have had to declare. During the wrestling tournament I met with Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko, the General Secretary of Russian PEN, and delivered to him the donation, and he gave me a receipt. The funds stayed off the crisis for then. Charges were dropped. A Russian Minister said, “I don’t understand. I was getting letters from as far away as Argentina!” Sascha answered him: “That is the kind of organization we are.” PEN continued to operate.

In Moscow I also met with Russian PEN members as well as with Turkmen author Rakhim Esenov, who was visiting Russian PEN. I had met Esenov a few weeks before in New York where he had won PEN America’s Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write award. In Turkmenistan Esenov had been charged with “inciting social, national and religious hatred using the mass media” because of characters in his novel The Crowned Wanderer. Set in the 16th century Mogul Empire, the story focused on a poet/philosopher/army general who was said to have saved Turkmenistan from fragmentation. The president of Turkmenistan Saparmurad Niyazov banned the book for portraying the main character as a Shia rather than a Sunni Muslim, and he imprisoned Esenov for several months. I still have the massive Russian language volume he shared with me, a work that had taken him years to write.

L to R: Russian PEN General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko and Russian PEN member outside Russian PEN office in Moscow and Rakhim Esenov, author of The Crowned Wander and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), 2006

At the Peace Committee conference earlier that month I’d presented a paper on the conference theme “The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World,” a broad and challenging topic which had inspired me to peer both backward and forward.

Below is the beginning of that paper with a link to the rest:

My first memory of a PEN meeting was sitting in someone’s living room in Los Angles writing postcards to free Wei Jingsheng from prison in China. At the time in the 1980’s he’d already been in prison several years of a fifteen-year sentence. I had no idea who this writer was thousands of miles away. I barely knew the other writers in that living room. On the coffee table would have been PEN’s Case List, which at the time was white sheets of paper stapled together.

We wrote and stamped our post cards for Wei and other writers that afternoon. I’m sure we were provided with background on his case. I pictured these cards fluttering into a jail somewhere in China and perhaps even into the cell of this stranger to let him know we had taken note of him and cared what happened. Looking back on the blue-sky afternoon as we sipped sodas and ate crackers and cheese, I see our act as a bit fleeting, an effort to imagine the fate of another writer who didn’t have our freedom to write and speak…[continue reading here]

Next Installment: PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN Journey 35: Turkey Again: Global Right to Free Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN’s work attests to the power of the individual and also to a particular vision of globalization that advocates the global right to free expression, a right that supersedes national restrictions.

In February 2005 Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s most noted writers, received threats and had his books burned by nationalist groups objecting to comments he made to a Swiss magazine while he was abroad. He referred to an Armenian “genocide.” While the Armenian community rallied to defend him, their support heightened certain nationalists’ protest in Turkey. Orhan wasn’t in Turkey at the time and hoped the turmoil would die down, but a government official in southern Turkey ordered the seizing of his books from local libraries so that they could be destroyed; it turned out later that there were none of his books in those libraries.

Novelist Orhan Pamuk and Sara Whyatt, International PEN Director of Writers in Prison Committee (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At Pamuk’s request International PEN kept quiet publicly at first. In mid-April Sara Whyatt, International PEN’s Director of the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) and I had lunch with Orhan in London to discuss how PEN could help if the threat escalated. I was International Secretary of PEN at the time. We agreed that publicity at this stage could exacerbate the situation; however, we explained that PEN centers could work behind the scenes by direct contacts with their governments, and PEN would be prepared to step into public action should the need arise.

Pamuk intended to stay outside Turkey until late April/early May, but then he would be returning home to Istanbul. Sara stayed in touch with him and shared a plan for action if the threats resumed on his return. Meanwhile we told him PEN would continue to lobby for a change in the Turkish Penal Code that allowed the charges. Key PEN centers, who had good relations with their own governments, and centers from countries with influence in Turkey would make approaches. London’s WiPC would make similar approaches to Turkish officials in Ankara and also through mechanisms at the United Nations, OSCE, and the European Union (EU). At the time Turkey was hoping to become a member of the EU and was attempting to align its judiciary codes with those required by the EU. PEN also worked with the International Publishers Association .

PEN prepared a statement on the situation in Turkey from early 2005 and kept it updated with news and recommended actions for the over dozen PEN centers ready to respond on this case. There was also press guidance should the centers receive queries. Meanwhile PEN continued to work on the other cases of over 70 writers and intellectuals charged or in prison in Turkey, which had long been a country with a revolving door of writers harassed, detained, attacked and sent to prison.

On April 1, 2005 World Peace Day the Turkish press reported:

The investigation against author Orhan Pamuk due to this statement saying, ‘One million Armenians and 30,000 Kurds were killed’ [in Turkey] has ended with a case in which he is accused of violating article 301 of the new Penal Code (same as famous article 159 in the former one) “Insulting Turkish nationality” and with the demand of being imprisoned between six months and three years. The first hearing will take place at Istanbul Sisli No. 2 First Instant Criminal Court on December 16, 2005.

The Public Prosecutor claimed that Pamuk’s remarks in Switzerland’s Das Magazin were an infringement of Article 301/1 of the Turkish Penal Code which states that “the public denigration of Turkish identity” is a crime and that those found guilty should be given sentences ranging from 6-36 months.

With threats renewed by the Public Prosecutor and a lawsuit filed against Pamuk that could result in a three-year prison term, Orhan finally gave PEN the green light to launch its campaign. PEN centers mobilized globally, including in Turkey.

“It is a disturbing development when an official of the government brings criminal charges against a writer for a statement made in another country, a country where freedom of expression is allowed and protected by law,” I noted at the time.

Pamuk’s hearing in December, 2005 was approximately ten years after renowned Turkish writer Yaşar Kemal had been called to trial on similar charges in January 1995. Pamuk told a colleague he would underline two things in his statement:

1. What I said is not an insult, but the truth.

2. What if I were wrong? Right or wrong, do not people have the right to express their ideas peacefully in this Turkey?

Eugene Schoulgin, PEN International Board Member and Müge Sökmen (Turkish PEN) at WiPC Conference, Istanbul, 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the judicial hearing, PEN members came to stand witness to the proceedings, including WiPC Chair Karin Clark, Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar, and International PEN board member and former WiPC Chair Eugene Schoulgin. Armored police officers escorted Orhan as protesters hurled a barrage of eggs and jumped on the car, punching the windshield.

PEN’s observers reported at the time: “The scenes around the first appearance of Orhan Pamuk before Sisli No. 2 Court of First Instance on 16 December 2005 at 11:00 were marked by constant shouting and scuffling turning ugly and violent at times. As those attending the proceedings left the court, eggs were hurled along with insults from the nationalists and fascists among the crowd lining the pavement across the street. This in full sight of the national and international media which had turned out in full…

“The courtroom was packed with well over 70 people—among them famous Turkish writers such as Yaşar Kemal and Arif Damar, and representatives of the European Parliament, several diplomats, members of Turkish and international freedom of speech organizations. The aggression and heckling inside and outside the court did not abate…”

The session ended after an hour and 15 minutes with an adjournment because the Ministry of Justice said that it needed more time to decide on the legal basis of the trial.

Hearing the news of postponement, International PEN President Jiří Gruša declared, “It is unbelievable that Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s best known and eminent authors, is in this situation. What it indicates is a complete disregard for the right to freedom of expression not only for Pamuk, but also for the Turkish populace as a whole. This decision bodes ill for other writers who are being tried under similar laws.”

He added, “PEN demands that the trials against all writers, publishers and journalists be halted and that the laws under which they are being tried be removed from the Penal Code. We also call on the Turkish authorities to put a definitive end to the penalization of those who exercise their right to freedom of expression.”

Hrant Dink, Journalist and Editor-in-chief Argos and Hilde Keteleer (Belgian Flemish PEN) at PEN WiPC Conference in Istanbul, Spring 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the time there were 14 other writers, publishers and journalists on trial under the newly revised “insult” law for criticizing the Turkish state and its officials. These included Ragip Zarakolu, publisher of books by Armenian authors and Hrant Dink, editor of an Armenian language newspaper, who was assassinated two years later.

For Pamuk the charges were dropped in January 2006, though on a technicality rather than on legal grounds protecting freedom of expression. The widespread opposition to Pamuk’s prosecution by PEN and other organizations succeeded, but as Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar noted in The New York Times: “There are many people abroad who fail to see beyond Orhan Pamuk’s trial. Saving a writer like Orhan Pamuk from prosecution may stand as a symbolic example on its own. But it is not an overall resolution for other intellectuals and writers that still face similar charges in Turkey.”

In March 2006 Orhan was the featured guest at PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee’s biennial conference held in Istanbul, hosted by Turkish PEN.

Writers in Prison Conference Istanbul 2006. L to R: Karin Clark (International PEN Chair WiPC), Sara Whyatt (Director WiPC), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary International PEN), and Sara Wyatt (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

On October 12, 2006 Orhan Pamuk won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

It could be said that the case of Orhan Pamuk signaled a long ride to the end of Turkey’s potential membership in the EU. In September 2006 the European Parliament called for the abolition of laws such as Article 301 “which threaten Europe’s free speech norms.” In 2008, the law was reformed, but according to the reform, it remained a crime to explicitly insult the “Turkish nation” rather than “Turkishness,” and in order to open a court case based on Article 301, a prosecutor was required to have approval of the Justice Minister; a maximum punishment was reduced to two years in jail. In November 2016 the members of the European Parliament voted to suspend negotiations with Turkey over human rights and rule of law concerns. In February 2019 the European Union Parliament committee voted to suspend accession talks with Turkey.

Turkey continues to be one of the most problematic countries for writers, especially on certain topics. While Turkey’s Penal Code relaxed for a while, allowing more space and freedom for writers, in the last years, the code and its execution has grown more onerous than ever.

*****

In that spring of 2005, I attended an event celebrating Press Freedom Day (May 3), hosted by Italian PEN in Venice. There I shared testimonials from writers on whose behalf PEN had worked. I share these again here:

** Cuban journalist and poet Jorge Olivera Castillo was conditionally released from prison in December 2004 after serving 20 months of an 18-year sentence. He wrote:

Your solidarity has been a light in the darkness. Thank you for having elected me as an Honorary Member…[I send] to all of you my gratitude for your messages of support and your unflagging concern.

** Nkwazi Mhango, Tanzanian journalist in exile, wrote:

Believe it or not tears are gushing as I am writing this message. No way in whatsoever manner my family and I can reciprocate your love and commitment to our plight. THANKS AGAIN AND AGAIN AND AGAIN MORE.

** On a sadder note the following was received from Tunisian internet writer Zouhair Yahyaoui, who died suddenly in March 2005 from a heart attack after he’d been released from prison:

Your email gave me once again a lot of hope for a better future in my country at a time when the dictatorship uses all illegal and barbaric means to make us give up and abandon all forms of protest…The fact that I continue to struggle to obtain our right to freedom of expression, here in Tunisia, is thanks to support of members of International PEN and other international organizations. Thank you again to you, to the Writers in Prison committee of International PEN and to all the PEN clubs all over the world who have supported me enormously during my imprisonment and who continue to do so.

** And from Chinese writer Jiang Qisheng:

… I am not a remarkable person. I am just an ordinary guy who did something extraordinary because it was the right thing to do…If my own case has any special significance it is only that it forces people to face a highly embarrassing fact—the fact that even now, in the dawn of the 21st century, a Chinese citizen can be imprisoned for what he says.

** I ended with a passage from the book This Prison Where I Live, the collection of prison writings drawn together by International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. In the afterword Malawian poet Jack Mapanje, who himself was in prison during the autocratic rule in his country, tells how bits of news managed to get smuggled into him in his concrete cell filled with spiders and cockroaches, scorpions and bats and bat droppings.

I found the note, unusually fat…I found a bulletin of typed world news and two poems by Brecht…Pat also enclosed two honorary membership cards from International PEN’s English and American centers, issued in London and New York respectively. They each bore my name. I had been made a member of PEN. Well, well, well!…

Then there was a cutting from Britain’s Guardian newspaper. Lord Almighty! A picture of Ronald Harwood, Harold Pinter, Antonia Fraser, and other members of English PEN reading from my book of poems in protest at the Malawi High Commission in London! It must sure have an effect, I thought. Ten thousand miles away, among the cockroaches of the prison where I lived I felt utterly humbled. Shattered. Such generosity, such warmth I surely did not deserve. All for one slim volume of poems? Why hadn’t I written more poems? I was dumbstruck. Despair vanquished. ‘I am belonged,’ I heard myself whisper.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 36: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part One

PEN Journey 21: Helsinki—PEN Reshapes Itself

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

In the old days, at least my old days, the Vice Presidents of PEN International sat in a phalanx on a stage while the Assembly of Delegates conducted business—revered writers, mostly white older men, along with the President, International Secretary and Treasurer of PEN in the center. If the Assembly business wore on, it was not unusual to see one or two of them nodding off. The role of the Vice Presidents was to provide continuity—many had been former PEN Presidents—to provide wisdom, contacts and gravitas. The designation was for life.

But times were changing. For instance, I had recently been elected a Vice President. I was a woman. I’d served PEN in several positions, including president of my center, founding board member of the International PEN Foundation and International Writers in Prison chair; I was a writer, though not of international renown, and at the time I was relatively young. I had been nominated by English PEN whose General Secretary thought it was high time more women sat on that stage. I didn’t relish sitting on a stage, but I was honored to hold the position. The Helsinki Congress in 1998 was the first when Vice President was the only role I had. I don’t recall if there was a stage at that Assembly. The fun was that I didn’t have to do anything. I could float between committee meetings, offer comments when relevant, wisdom if I had any and be called upon for whatever insight or experience or task might serve. (Traditionally the Congress organizers paid for the Vice Presidents’ registration and hotel, but from the start I chose to cover my expenses as a way of contributing to PEN. The expense of Vice Presidents attending was growing more and more difficult for the host centers; on the other hand many Vice Presidents wouldn’t be able to attend otherwise.)

Program for 65th PEN International Congress in Helsinki, Finland

At the 65th PEN Helsinki Congress held at the Marina Conference Center on the waterfront, a short walk from the city center, delegates and PEN members from 70 centers around the world gathered. The Congress’ theme was Freedom and Indifference. My memories are of meals on the water with colleagues, of eating fish and mussels and walking among old and very new buildings, visiting the architecturally stunning Contemporary Art Museum and other cultural excursions I often didn’t have time to attend when chairing the Writers in Prison Committee.

At the Congress I could even sit in on a few of the literary sessions which included abstract topics such as Where Does Indifference End and Tolerance Begin?—The Role of the Intellectual in Contemporary Society; Eurocentrism and the Global Village; The Cultural Gap Between East and West; The Ambivalence of Otherness: Identity and Difference; Crime Literature Portraying the Society; On Cultural Creolisation (mixture) and Borderlands. I confess reading those topics now stirs memories of sleepy academic afternoons, but the writers presenting included some of the engaged and engaging writers of the day, including Wole Soyinka, Caryl Phillips, Andrei Bitov and many Finnish and Scandinavian writers such as Sweden’s Agneta Pleijel.

At the Congress I still concentrated on the work of the Writers in Prison Committee which former Iranian prisoner Faraj Sarkohi attended. The year before he had been a main case for PEN, imprisoned and tortured and threatened with execution. In introducing his presence to the Assembly of Delegates, PEN President Homero Aridjis noted that PEN members could take satisfaction in having played an important role in obtaining his release. Sarkohi had managed to get a passport and was now living in Europe where he’d resumed his literary and journalistic activities.

Moris Farhi, the new WiPC Chair, introduced Sarkohi to the General Assembly of Delegates where Sarkohi said he owed his life and freedom to the international movement initiated by PEN both in the London headquarters and in the PEN centers around the world. For the first time in 20 years the Iranian government had been forced to release someone they had wanted to kill, he said. His release demonstrated to other writers in Iran that release was possible even if the government wanted to execute them. Sarkohi had briefly spoken with another PEN main case in prison who told him he was no longer worried, knowing now about the international support he was receiving.

Sarkohi explained that writers were considered by the despots in Tehran to be guilty because they worked with words, because they tried to discover and express in words different aspects of truth. It was believed writers made magic, he said. Everyone knew the magical power inherent in words so the writers were arrested. The government forced them to deny themselves, to accept false charges, and in this way they killed writers mentally. When a writer was forced by physical and mental torture to deny himself, his ideas and his work, his power of creation died, and he was killed as a writer. When Sarkohi was in solitary confinement, he remembered the way in which those suspected of magic were treated in the Middle Ages. People were arrested and burned and told “If you live, your magic powers are proved and we kill you. If you die, it is established that you do not have magic powers.’—but you were dead anyway. Writers were regarded as the new practitioners of magic in this century and that treatment by tyrants and despots was that of the Middle Ages.

Sarkohi described how he and colleagues who were still in prison had issued a new Charter, inspired by the PEN Charter, in which they protested censorship, both by the government, self-censorship and by the public such as groups which beat up a writer in the street. The Charter also demanded the right for writers to organize an association, something not permitted in Iran. He worried now about the fate of his colleagues in Iran because five years ago when writers published a Charter and sent the text abroad, the government had reacted and killed a famous translator and dumped his body in the street and murdered a famous poet in his home.

Sarkohi noted that German PEN and other PEN centers had prepared a resolution for the Congress making it clear to the Iranian government that International PEN was watching the fate of Iranian writers so they would know before they arrested or killed someone that Iranian writers were supported. He believed that support let all the world see that writers were not alone.

L to R: Mansur Rajih from Yemen, one of the first ICORN guests in subsequent years, and Iranian writer Faraj Sarkohi, former WiPC main case at PEN International’s 65th Congress in Helsinki, Finland, 1998

While the Helsinki Congress focused on the traditional work of PEN and its Committees, it was also a watershed Congress addressing the structure and governance of PEN. The Ad Hoc Committee, elected at the previous congress in Edinburgh (see PEN Journey 20), had examined the draft of revised Regulations and Rules and presented a final draft for the Assembly’s adoption. The revised Regulations and Rules were the product of two years’ work and consultations among centers. These were the first amendments to the Regulations of PEN since 1988 and the first major revision since 1979.

International PEN’s reform to provide more democratic decision-making, more communication between the International and the Centers and more transparency was not an entirely smooth transition and reflected a larger global trend at the time among the 100+ nationalities represented in PEN.

At the Congress a new International Secretary—Terry Carlbom from Swedish PEN—was elected as the only candidate, Peter Day, editor of PEN International magazine, having stepped down from consideration because of health reasons. The former International Secretary Alexandre Blokh, who had served for 16 years, didn’t attend the Congress, but was elected a Vice President and returned to subsequent Congresses.

Marian Botsford Fraser of PEN Canada, representing the Ad Hoc Committee, presented the new proposed Rules and Regulations, noting that they were “the nuts and bolts or the strings and hammers of a piano or the engine of a car or mother board of a computer. In any case their workings were unfamiliar to most writers,” she said. “It was as if we had been asked to rebuild the engine of a 1979 Audi, a vehicle renowned for the complexity of its construction. Frankly I can think of only one more difficult assignment for nine writers and that would have been to collaborate on the writing of a novel.”

She noted that the Committee of nine was a diverse collection of individuals with the wisdom that democracy sometimes magically bestowed upon its practitioners. The Edinburgh Assembly had chosen a group of people who represented the linguistic, cultural and geographic diversity of PEN and who brought to the table individually and collectively their commitment to the history and the future of PEN, their desire to remain true to the spirit of the Charter of PEN and to the identity of PEN as first and foremost an organization of writers working together to protect language, literature and the fundamental human right of freedom of expression. “We brought to the process different and strongly held views on how to make the regulations that we were charged with drafting embody those principles, how to create a structure that would become the foundation for the future of this organization,” she said.

She thanked certain Ad Hoc members, who in fact did seem to have some knowledge of the workings of a 1979 Audi and added special thanks to Administrative Director Jane Spender “who took the whole mess of scribbled bits of paper, half sentences, cryptic clauses, clearly articulated ideas and sometimes incoherent good intentions back to London, and through another process of consultation and discussion and writing and rewriting was able to turn all of this into two documents that were sent to all Centers as Draft Regulations and Rules.” Homero Aridjis, the new International PEN President, also participated in this task along with the Ad Hoc Committee.

As I read through the minutes of the Helsinki Assembly, I recalled the tensions that arose, particularly around single words such as “a-political”—after all we were an organization of writers where words and translation of words mattered—and around events that had happened off stage. Changing the way a 77-year old organization worked was perhaps more like shifting from an Audi into an SUV which could hold more people, handle more difficult terrain but also consumed more fuel and energy. But metaphors aside, after debate and discussion, agreement was ultimately achieved.

The most important change was the move to form an Executive Committee that would be the main implementing body for International PEN, a step agreed by most all Centers who chose to participate in the process. Instead of government by a small executive of the President, International Secretary and Treasurer between the Assembly of Delegates’ meetings, an Executive Committee of seven members drawn from the centers around the globe and elected for three-year terms (and up to six years) would operate along with the three executives of PEN. The election for the first Executive Committee was to take place at the 1999 Congress in Warsaw. Until then the Ad Hoc Committee would continue to function and also act as a Selection Committee to assure qualified candidates were put forward.

Details of this new structure were modified over the next twenty years. The Selection Committee evolved into an elected Search Committee to assure qualified candidates were proposed for the various offices and to gather their required papers. The Search Committee was not set up to be a guardian council or an arbiter of candidates, but a facilitator for the process. In 2005 an Executive Director was added to the equation. As with any organization, PEN keeps growing and changing, but the essential structure to broaden and democratize governance of this global organization was set in place in 1998 in Helsinki. I’m not sure what vehicle I would compare PEN to these days, probably not a finely tuned Audi, but it continues to drive.

As for Vice Presidents, that office was not changed during this watershed period of reform, but over time, PEN changed the role of Vice Presidents and designated the ex-Presidents as Presidents Emeritus instead and divided the Vice Presidents into two equal categories with twelve in each: those elected for “service to PEN” and those designated for “service to literature;” the later included internationally renowned writers and Nobel laureates such as Nadine Gordimer, Toni Morrison, Svetlana Alexievich, Orhan Pamuk, Margaret Atwood, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, J.M. Coetzee.

When I became International Secretary (2004-2007), the Executive Committee (now called the Board) and I proposed, and the Assembly agreed, that Vice Presidents’ terms should be limited, at least in the category of service to PEN—ten years or sometimes twenty—then most would move to emeritus status. It took another ten years before this change was implemented.

These are arcane details but illustrate PEN as an organization striving to keep those experienced engaged at the same time keep the organization unencumbered so it can grow and bring in new ideas and talent. It is a vehicle constantly re-tooling with the Charter as its base and a body of creative members whose greatest talents are not necessarily in rules and regulations yet who respect their necessity. Vice Presidents Emeritus, as I now am, are invited to the Congresses and show up and are still sought out for the bit of history we know and for the bits of wisdom we might offer from our experience and for continuity. We knew PEN in the days of the Audi, though even then it was perhaps not so finely tuned, I think, but it got from here to there across the globe as it still does.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 22: Warsaw—Farewell to the 20th Century

PEN Journey 20: Edinburgh—PEN on the Move, Changes Ahead

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest

I begin with the memories…

Castle Rock and Edinburgh Castle in Edinburgh, Scotland

—the imposing walls around Castle Rock which stands above the city of Edinburgh and dates back to the Iron Age,

—the 12th century castle/fortress inside,

—the Old Parliament building,

—the New Parliament building where we sat in high-backed theater-style seats in an arena,

—the dorm room residence inside Pollack Halls where we stayed at Edinburgh University near the city center, beside an extinct volcano,

—the receptions at Parliament House and Signet Library and the City Arts Center where there was never quite enough food for the overly hungry delegates who descended upon the platters,

—the UNESCO seminars on women and literature, including my paper The Power of Penelope,

—and elections, so many elections and speeches—three candidates for Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) Chair, seven candidates for International PEN President, nine Ad Hoc Committee members as precursors to a new governing board for International PEN.

These were the first contested elections I remembered in International PEN. A wider democracy was spreading with ballots and speeches. I also remember the tension and the occasional flares of anger, and the effort to hold us all together and ultimately the confident results and the determination to move forward in unity. International PEN President Ronald Harwood warned that while PEN badly needed to democratize “power” so it wasn’t too centralized, residing in the hands of a few, the delegates should not make the struggle personal and should go forward with a sense of humor. We were an organization of writers, not the government of the world, he admonished, warning members not to confuse bureaucracy with democracy.

—I remember the trip to Glasgow where a few of us had a stimulating visit and tea at the home of James Kelman (Booker Prize winner How Late It Was, How Late) who had been with us in the protests in Turkey a few months before (see PEN Journey 19) and the old Mercedes tucked in the garage in the working class neighborhood.

—And the Edinburgh International Festival, including the Edinburgh Book Festival, happening simultaneously all around us.

—And finally the exquisite August light in Scotland.

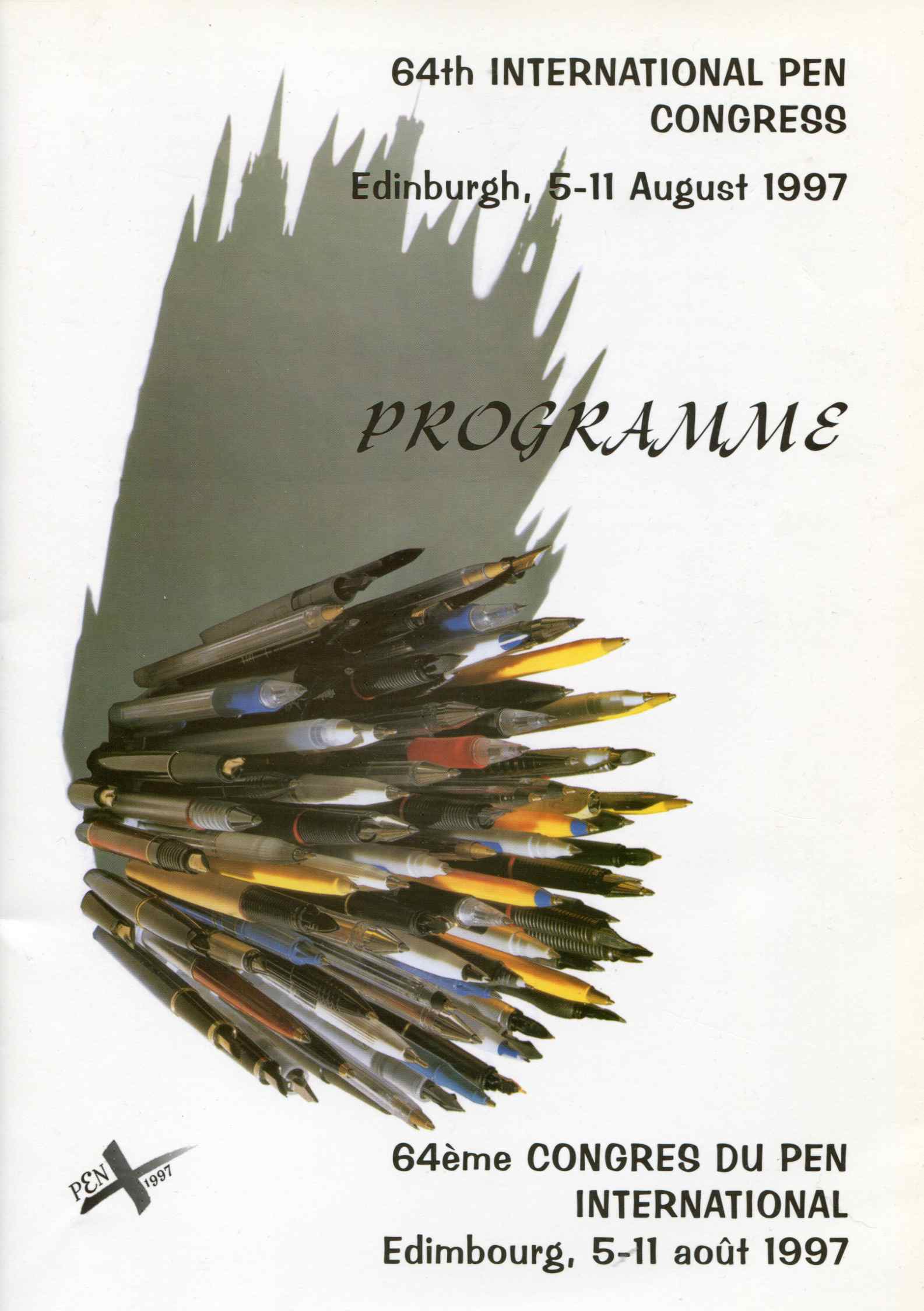

Program for 1997 PEN International Congress

I begin with memory then plunge into the minutes and documents of the 64th PEN Congress August, 1997 when delegates from 77 PEN centers around the world gathered. The Congress theme Identity and Diversity posed the questions:

In the contemporary world there are intense pressures, political or commercial, deliberate or unconscious, towards an imposed uniformity. One example is the effect on language. Indigenous languages, which embody particular traditions and experience, are in many countries under threat of displacement and extinction. These tendencies are inimical to literature which depends on its local personality for its color and effectiveness even when it achieves universal significance.

On the other hand, we live in an inter-dependent world where peace, prosperity and ultimately even survival, require co-operation. This international co-operation may be assisted by the use of a few languages which are widely understood. International exchange of the appropriate kind can also bring cultural enrichment.

How can these apparently contradictory objectives of diversity and co-operation be reconciled? Does literature have a role in this respect?

As with most abstract themes and questions, there is no simple answer, but the theme was a pivot, in this case both in the literary sessions and inadvertently in the business of PEN as the organization sought to restructure itself. Because this was my last congress as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee, the work of that Committee absorbed my focus. My two reports—one the official printed International PEN Writers in Prison Committee report and the other an address to the Congress—observed, and in a fashion related, to this theme:

[Written report:]

PEN Writers in Prison Committee Report, 1997

Tension between the individual and the state underlies the work of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. In some countries constitutions and governing principles are set out to protect the individual from the state, but in the majority of countries which PEN monitors where writers are imprisoned, threatened or killed, the state is organized to protect itself from the individual. Whether those countries be totalitarian regimes like China, Myanmar/Burma, Syria, Vietnam, Cuba or democracies like Turkey and South Korea, when the state holds itself superior to the rights of its individual citizens, freedom of expression is seen as a threat to stability rather than a sign of stability.

In 1997 the Writers in Prison Committee has defended individual writers in at least as many of the new and older democracies around the world as in totalitarian states. Since 1990 dozens of nations in Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Asia have restored or initiated multi-party democratic elections. The turn to the democratic process initially freed up restrictions on writers and journalists in many countries. However, after the first flush of these freedoms, after dozens of independent publications sprang up in Argentina, Belarus, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Russia, Sierra Leone, Zambia, etc., tensions mounted between the individual voice and the state. Restrictions and press laws followed, and writers once again found themselves facing prison terms on such charges as “insulting the President”, “writing derogatory statements against the government and government officials”, and “seditious libel.”

In some states like Sierra Leone harsh restrictions on the media preceded coups and the loss of democracy. Reporting restrictions and brief detentions of journalists enforced by the crumbling Mobutu government in Zaire (now Congo), did not serve to protect it from its eventual collapse. Earlier this year the political crackdown in Belarus was preceded by severe censorship and curtailment of publications. The collapse of the government in Albania was followed by severe restrictions on publications and attacks and death threats on journalists and writers.

When a coup occurs and democracy fails, the consequences for free expression are usually disastrous as has been seen in Nigeria where journalists continue to serve lengthy prison terms and are arbitrarily detained, sometimes for months without charge. Another instance of a threat to freedom of expression in Nigeria is that of PEN member and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka who is among 12 dissidents charged in Nigeria this year with the capital offense of treason. Soyinka remains free outside the country but is certain to be imprisoned if he returns.

Pressure on writers and the media continued or increased in many new and old democracies, including Algeria, Argentina, Bosnia, Cameroon, Croatia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Indonesia, Kyrgystan, Mexico, the Palestinian authority, Turkey, Uganda and Zambia. Pressures took the form of legislation which required publications to obtain government licenses and approval and/or required journalists to have state-approved credentials. Pressure also took the form of arrest, arbitrary detention and death threats…

When democracy fails, there are hosts of reasons embedded in history and politics. Curtailment of free expression is not necessarily the precipitating cause, and curtailment of free expression does not always lead to failure of democracy. However, repression of the written word and of the writer remains at the very least a symptom and often a warning light that political failure lies ahead…

The report goes on to outline situations of individuals under threat. Reading these reports is reading a political history of the time, told through the circumstances of individual writers. One of the highlighted cases at the Congress in 1997 was that of Iranian writer Faraj Sarkohi who’d signed a petition calling for freedom of expression, along with 134 other Iranian writers. Sarkohi had been kidnapped by the Iranian secret service while on his way to visit family in Germany; he was tortured and threatened with execution. Because of the worldwide protests by PEN and others, he was eventually released the following year and sent into exile.

Visiting the WiPC meeting in Edinburgh, Egyptian professor Nasr Hamed Abu-Zeid, a leading liberal theologian on Islam, told his story of being declared an apostate for his research and forced to divorce his wife, also an academic. They had fled Egypt where apostates could be killed. Şanar Yurdatapan, the Turkish activist who’d organized the Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression which many of us attended earlier that spring, had just been released from prison and also spoke to the meeting. The cases of Sarkohi and Abu-Zeid and Şanar were among 700 on the WiPC records.

[Address to Assembly of Delegates:]

After four years chairing International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, I’ve come to appreciate the simplicity of the Committee’s mandate and the complexity of its execution. To defend the individual’s right to free expression is to defend not only the essence of literature but also a cornerstone of free society. Our defense begins with the individual writer, but inevitably we are caught in the movements of politics and history where individuals struggle to shape, divert or oppose the tides. One of the most significant developments in the past few years has been the expansion of multi-party democracies across the globe, a development that at first glance would signal progress for free expression. However, from our work we have seen that democracy takes more than a polling booth and a list of candidates on a ballot to come to fulfillment. Freedom of the written word is essential for a democracy to work over the long term, and attacks on this freedom usually foreshadow larger repression and even the failure of the democracy itself.

This year PEN has seen repressive laws enacted and/or writers arrested and killed in the new and old democracies of Albania, Algeria, Argentina, Belarus, Bosnia, Cambodia, Cameroon, Croatia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Mexico, Russia, Palestinian territory, Peru, Sierra Leone, South Korea, Turkey, Zambia. Many governments have passed or tried to pass laws to bring publications under their control through licensing and government-approved credentials. These laws have been followed by the arrest of writers.

Repression remains the most severe in totalitarian states such as China, Cuba, Iran, Myanmar (Burma), Nigeria, Syria, Vietnam. China continues to imprison more writers for longer periods of time—over 70 individuals, many serving 10-20 years—than any other country. Many of the writers who were imprisoned during Tiananmen Square have been released in the past two years, but others have taken their place. The Writers in Prison Committee is watching with great concern legislation which could lead to restrictions on writers in Hong Kong as China takes over. The Committee is also following closely the continued repression in Myanmar (Burma) where prison conditions remain harsh and at least 25 writers remain behind bars, many with sentences exceeding ten years…

Many of the cases in Africa this year came from new democracies struggling with issues of free expression, including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Zambia. The military dictatorship of Sani Abacha in Nigeria continued to occupy the focus of many PEN centres who worked on behalf of writers still in prison. Protests from a number of PEN centres assisted in the release of two Nigerian writers…Our Committee heard a statement from PEN main case Koigi wa Wamwere from Kenya, where riots have broken out after calls for democratic reform. Centres around the world have lobbied for his release, and he is now out on medical bail, and the Writers in Prison Committee has assisted his return to Norway where he is living. He sent a message thanking PEN for its work on his behalf. He writes, “When dictators arrest writers, they guard them with more guns and soldiers than they guard enemy armies in captivity. Dictators fear ideas and writers more than they fear guerrilla armies. Afterall they know that without ideas even guerrilla armies would wither away and die…”

In Latin America PEN continued to protest this year the imprisonment and detention of writers in Cuba. This spring the Writers in Prison Committee issued its report on its Cuba trip last fall, focusing on dissident writers who often had to choose between prison and exile…In Peru, though legislative and judicial reforms have occurred in the last years, at least 11 writers there have reported threats and/or attacks from both governmental and non-governmental sources, and sixty writers and journalists have reported death threats or attacks in Argentina…

The Writers in Prison Committee continues to work closely with freedom of expression organizations around the world, sharing our research and disseminating via the internet so that when a writer is arrested as far away as Tonga, the King of Tonga suddenly found himself receiving faxes from all over the world.

Over the years the political tides have shifted, but members’ work on behalf of individuals and the friendship of writer to writer remain even after the writers are released. This year we saw releases in Cameroon, China, Cote d’Ivoire, Cuba, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Kuwait, Maldives, Myanmar (Burma), Nigeria, Peru, and Russia. On occasions we have gotten to meet and know the individuals personally. This year when the Nigerian government picked up Ladi Olorunyomi, the Writers in Prison Committee was quickly alerted. A number of us had had the opportunity to meet with her husband Dapo, a prominent editor and dissident now living in exile in the United States. Isabelle Stockton, our Africa researcher and I spoke in the morning, and she called him to gather more details. When I phoned him later in the day, he said, “I was going to call you, but before I could, PEN was already calling me.” As soon as we determined that Ladi Olorunyomi had not been charged with a crime, had no access to lawyers and was not allowed to see her family, we put out a Rapid Action to our centres and shared the information with other freedom of expression organizations all around the globe. During her almost two months in captivity we were able to monitor the case, share information, and hear with great relief when this writer and mother was finally released.

Dapo, who had secretly fled Nigeria a year earlier lest he be imprisoned, wrote PEN, “Thank you for everything! I am very grateful, but I lack the words, appropriate enough to convey my gratitude…to our good friends at PEN International.”

The business of PEN throughout the year and at the annual Congress also included the work of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, Women’s Committee, Peace Committee, the growing activity of the Exile Network and the literary sessions. The UNESCO seminars on Women’s Cultural Identity linked to the seminars on Literature and Democracy at the Guadalajara Congress the year before. In many parts of the world women still did not have full democratic rights. Significantly, in Latin America only 10% of books published were by women, and in Africa it was as few as 2%. But I must leave others to elaborate these activities.

At the 64th Congress results of the many elections yielded the next group of leaders who would take the organization into the last years of the 20th Century and into the transformation of governance. At the Congress Ronald Harwood was elected a Vice President as I had been at the previous Congress and as such we stayed connected and in the wings for the changes ahead.

Election results of the 64th PEN Congress:

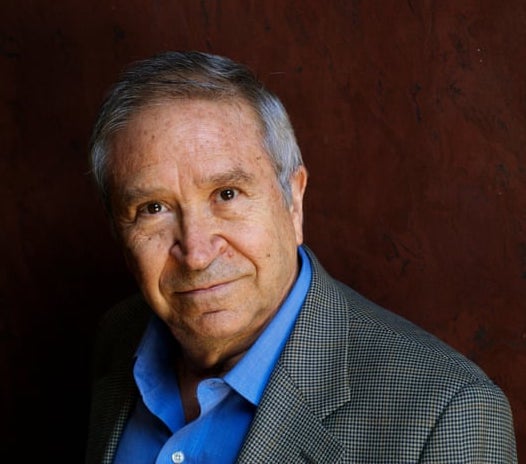

Homero Aridjis

Seven candidates stood for the presidency from Europe, Africa and the Americas though one dropped out. Homero Aridjis of Mexico, well-known poet, journalist and diplomat, was elected the next President of International PEN.

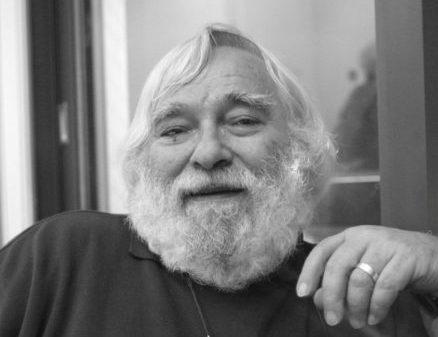

Moris Farhi

Novelist Moris Farhi, former chair of English PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, was elected chair of the WiPC. The two runner-ups Louise Gareau-Des Bois (Quebec PEN) and Marian Botsford Fraser (PEN Canada) agreed to serve for a year as Vice Chairs. In 2009 Marian Botsford Fraser was elected chair of WiPC and served till 2015.

The new Ad Hoc Committee elected at the Congress included Marian Botsford Fraser (Canada), Takashi Moriyama (Japan), Boris Novak (Slovenia), Carles Torner (Catalonia), Jacob Gammelgaard (Denmark), Vincent Magombe (Africa Writers Abroad), Gloria Guardia (Colombia), Gordon McLauchlan (New Zealand) and Monika van Paemel (Belgium). This committee was charged with considering all the restructuring proposals and preparing a draft for discussion and adoption by the Assembly of /Delegates at the 1998 Helsinki Congress. The Ad Hoc Committee was also tasked as a Nominating Committee to search for a new International Secretary. Alexander Blokh, re-elected for another year as International Secretary, planned to step down at the 1998 Helsinki Congress. Little did I know nor aspire to take on that role six years later.

New PEN Centers voted in at the Edinburgh Congress included Cuban Writers in Exile, Somali-speaking Center, Sardinian PEN Center, and a reconstituted Mexican PEN Center.

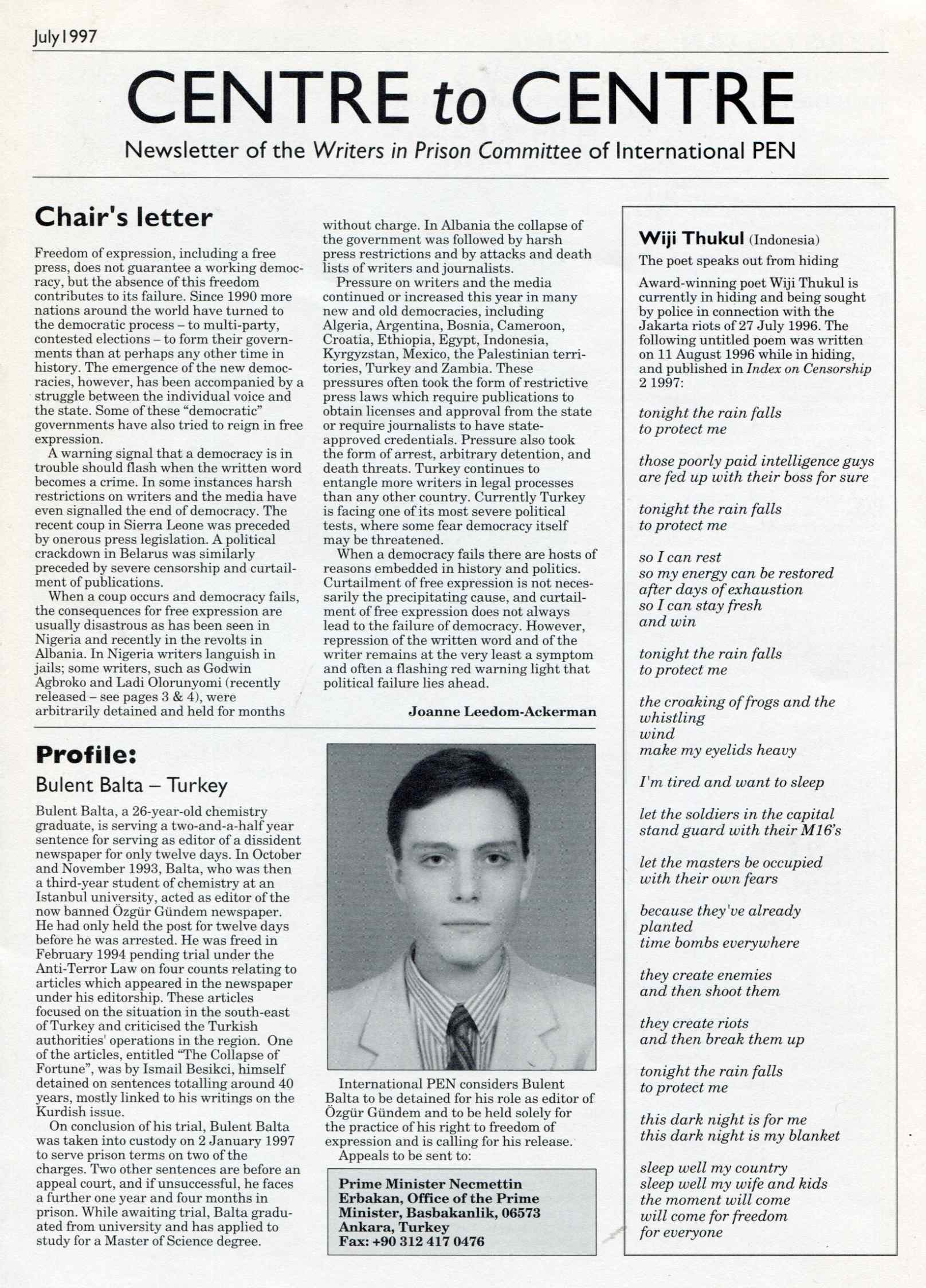

PEN International’s Writer in Prison Centre to Centre newsletter, July, 1997

Next Installment: PEN Journey 21: Helsinki–PEN Reshapes Itself