Posts Tagged ‘Hrant Dink’

PEN Journey 43: Turkey and China—One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

January 2007 began with an assassination. The Board of PEN International was just gathering in Vienna for the first meeting of the year when board member Eugene Schoulgin got a phone call letting him know that our colleague and his friend Turkish-Armenian editor Hrant Dink, had been gunned down in Istanbul and killed. Many of us had seen Hrant at the PEN Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul in March.

Editor-in-chief of the bilingual Turkish-Armenian newspaper Agos, Dink had long advocated for reconciliation between Turks and Armenians and for Turkey’s recognition of the Armenian genocide early in the century. Dink had received death threats before and had himself been prosecuted for “denigrating Turkishness,” but as with Russian colleague Anna Politkovskaya, Dink’s assassination stunned us all and set off widespread protests in Turkey and abroad. Eventually a 17-year old Turkish nationalist was arrested and convicted, but not before police were exposed posing and smiling with the killer in front of a Turkish flag.

PEN International Board Meeting, Vienna, January 2007. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary; Jiří Gruša, International President; Caroline McCormick, Executive Director; Judy Buckrich, Women Writers Committee Chair; Elizabeth Norgdren, Finish PEN; Eugene Schoulgin, Norwegian PEN; Franca Tiberto, Search Committee Chair; Sibila Petlevski, Croatian PEN; Britta Pedersen, International Treasurer; Eric Lax, PEN USA West; Mohamed Magani, Algerian PEN; Kata Kulavkova, Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair; Frank Geary, Programs; Karen Efford, Programs.

The work of PEN is, at its heart, personal. It is writers speaking up for and trying to protect other writers so that ideas can have the freedom to flow in society. In league with other human rights organizations, PEN also advocates to change systems that allow attacks and abuse. At times the work can feel ephemeral when the systems don’t change, or make progress only to regress. However, the individual writer abides, and PEN’s connection to the writer stands.

During my tenure working with PEN, Turkey and China have been the two countries that have imprisoned the most writers. For a period both nations appeared to be advancing towards more open societies but soon retreated. In the early 2000’s as Turkey aspired to join the European Union, the country operated as a democracy with a more independent judiciary; fewer writers became entangled in the judicial processes. However, in 2007 the democratic transition in Turkey began to veer off course and has continued a downward spiral towards authoritarianism ever since.

China also promised to become a more open society with the advent of the Olympic Games in 2008. Democracy activists inside and outside of China grew hopeful. In this climate, PEN held an Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in Hong Kong in February 2007; it was PEN’s first in a Chinese-speaking area of the globe. Over 130 writers from 15 countries gathered, including writers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and many of PEN’s nine Chinese-oriented centers as well as members from Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Nepal, Australia, the Philippines, Europe, and North America.

Both China’s and Turkey’s Constitutions protected freedom of expression in theory, but in practice the protection was lacking. Instead, laws and regulations prohibited content. In Turkey, exceptions included criticism of Ataturk, expressions that threatened “unitary, secular, democratic and republican nature of the state” which in effect targeted issues around Kurds and Kurdish rights. In China, the Constitution noted that “in exercising their freedoms and rights, citizens may not infringe upon the interests of the State, of society or of the collective, or upon the lawful freedom and rights of other citizens.” The state was the arbiter.

The Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 took place at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories with programs also at Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club. The theme Writers in the Chinese World celebrated Chinese literature and a dialogue among PEN’s Asian centers and also explored issues of translation, women, exile, peace, censorship, internet publishing, freedom of expression and PEN’s strategic plan.

Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories. Over 130 writers from 20 PEN centers in 15 countries gathered for the four-day conference.

However, 20 of the 35 mainland Chinese writers who planned to attend were prevented or warned off by government authorities, including the President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) Liu Xiaobo, who later won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 while imprisoned in a Chinese jail. Qin Geng had his permit rescinded and two writers—Zan Aizong and Zhao Dagong—were stopped at the border and denied permission to exit though they had permits. (Two overseas Chinese writers who attended and had other citizenship—Gui Minhai and Yang Hengjun—are now in prison in China and are PEN main cases.)

In addition, the Chinese Communist government banned eight books, including one by Zhang Yihe, an honorary board member of the ICPC who had been invited to speak at the conference but instead was warned not to attend.

China’s promised opening of its society was already contracting, and the restrictions bore a harbinger of events to come both for writers and eventually for Hong Kong. The conference attracted wide press attention with articles in Chinese and English newspapers in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and globally via the BBC and newswire services. Renowned Shanghai playwright Sha Yexin, poet Yu Kwang-chung (Yu Guangzhong) from Taiwan and Korean poet Ko Un, short-listed for the Nobel Prize for Literature, attended. But the restrictions on the mainland Chinese writers cast an ominous shadow and grabbed the largest regional and international headlines.

“PEN has nine centers representing writers in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and abroad and has great respect for Chinese Writers and Chinese literature,” International PEN President Jiří Gruša told more than 40 reporters at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, “but we are very concerned by the restrictions on writers in mainland China to write, travel and associate freely.”

In honor of the absent writers, an empty chair sat on the platform for each session of the four-day conference.

Press Conference at Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, February 2007; L to R: Translator, Journalist Gao Yu (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Jiří Gruša (PEN International President), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary)

In 2007 more than 800 writers were under threat worldwide, and at least 33 writers were in prison in China. A number of the attendees at the conference had been imprisoned and been main cases for PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), including celebrated Korean poet Ko Un and Chinese journalist Gao Yu, both of whom addressed the conference. They knew firsthand the role of the writer in the struggle for freedom, and they knew the support PEN had given, observed one of the conference organizers Yu Zhang, General Secretary of the ICPC, half of whose members lived in mainland China.

“I am no longer afraid of anything,” one Chinese writer unable to attend said in a message to the conference. “Our bodies and our spirits are our own. To speak of ugliness and injustice we have to shout, but our throats are cut when we do.”

“We are willing for some things to be burned in the soil so a new leaf will come,” added another mainland writer in a message to the conference.

“It is important that all writers get together, and all writers protect the freedom of speech and free expression. We must write what’s in our hearts and write as a witness to history,” said Qi Jiazhen, who spent 10 years in a Chinese prison and now lived in exile.

Owen H.H. Wong of Hong Kong’s English-Speaking PEN Center pointed out that Hong Kong was a meeting point of East and West, North and South, Leftists and Rightists and Modernization and Classic writing. He noted that before the 1997 handover, Hong Kong writers saw themselves as writers in exile. Only those born in Hong Kong regarded themselves as Hong Kong writers. Now most publishing houses in Hong Kong were funded by the Communist government, and free expression in Hong Kong was threatened and controlled.

Yu Jie, a Beijing-based essayist and author and vice President of ICPC, spoke at the Foreign Correspondents Club noting that even though he was able to attend the conference and speak to the foreign media, he had not been able to get published in mainland China. For mainland writers, Hong Kong was a place where freedom of expression and freedom of the press still existed, he said. “It’s as if those of us in the mainland have our heads immersed in water and cannot breathe, but Hong Kong allows us to stick our heads above the surface of the water, and for a short time, breathe freely.”

He predicted that the authorities would later “settle the score” with the writers and publishing houses. He was in fact later arrested, tortured and imprisoned for his writing. In 2012 he emigrated to the United States.

PEN International Panel at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference. L to R: Conference organizers included Yu Zhang, (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Caroline McCormick (PEN International Executive Director), Chip Rolley (Sydney PEN)

“Existing in the unofficial nooks and crannies of an emerging civil society in China, ICPC is determined to insist that their country live up to the rights guaranteed in its Constitution,” said another conference organizer, Chip Rolley, Vice President of Sydney PEN. “This continuing work will ensure that there is indeed a turning point for PEN in China and the wider Asia and Pacific region, and that this historic conference will not dissipate like smoke.”

In his keynote address Taiwanese writer and poet Yu Kwang-chung called for “all the writers and the poets across the Chinese world” to strengthen the channels of mutual exchange, and make efforts to find a consensus on basic issues such as the formation of a common national culture (which includes in particular the establishment of joint aesthetic and literary values) in order to “make a valuable contribution to preventing war and maintaining peace.”

Attendees launched a dialogue on literature as well as on networking among PEN’s Asian centers with a regional strategy for freedom of expression and translation. The conference was part of PEN International’s program to develop the regions in which PEN operated by connecting existing writers and PEN centers and also developing new centers in countries starting to open up such as Myanmar/Burma. Often a PEN center was one of the first civil-society organization to set down roots when authoritarian controls began to relax. [A Myanmar PEN Center was established in 2013.]

In a panel on Literature and Social Responsibility panelists noted that free speech and writers’ responsibilities were the basis of social prosperity and that PEN was a bridge between writers and their responsibilities.

Participants at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference from China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Philippines, Vietnam, Nepal, including speaker Yu Kwang-chung (Taiwan) seated in center.

Chen Maiping of ICPC read a message from Zhang Yihe, the mainland novelist who was to have been on the panel but who had been prevented from attending. “There is a saying: human hearts are like water, while people’s favor and loyalty feel as heavy as mountains. During these ten plus days since my books were banned, so many people have shown their concern I have nothing to give in return for their kind support other than to express my gratitude on paper. Writing is my only means of self-expression. Writers have always been prisoners of language and words. It is not an easy affair for me to live, nor can I die in peace. I can only write…In China we talk about ‘literature as a vehicle for the Tao (the Nature, the Way).’ People have talked about this for thousands of years. However, those who have written the best literature are exactly those who never think about their social responsibility. Zhang Bojun [the author’s father who was a scholar and a minister in the Chinese government in the 1950s and persecuted during the 1957 Anti-Rightist campaign in Mao’s Cultural Revolution] was an example of this. In my view his achievements were much greater than many of the contemporary writers, artists and painters. If a writer has too strong a responsibility, he may have no achievements at all.

“For several decades, literature has been tied together with ‘revolution’ and ‘reform.’ I can’t bear such responsibility. I can only recall the past. I do not have such social responsibility tied to ‘revolution‘ and ‘reform.’ I am out of date. There are so many people singing praise for the society, why not allow an old woman like me to sing a little song of my own. I am only a piece of withered leaf. I hope that I can decay quickly so that I may become a new leaf soon. “

Chen Maiping also read “Writing in Anger” by Liu Shu, another mainland writer prevented from attending. “The conflicts between our hearts and reality and an unwillingness to keep silent are the driving forces for my writing. The disgraceful politics have turned us into dissident writers. Chinese dissident writers write in isolation. The marginalized position of dissident writers has marginalized their writing. This is very different from the West. The Eastern people have the ability to suffer and digest their sufferings. This kind of ability enables writers to ignore the reality and to become numb to the suffering of their people. They choose to write only about ‘pleasant things to lighten the load on their hearts.’

“The cruelty of reality fills their lives with ‘submission.’ The writers are swollen and weighed down with humiliations and sufferings; they have lost the anger created by their reality. They have no anger at the past, nor do they imagine a future. They only write about meaningless, shallow and trivial affairs. My anger comes from my refusal to accept and make peace with this reality. I have been detained four times because of my ideas. We puzzle over social phenomena but we long for peace. The way to calm our anger is to write…I must speak for citizens who were screened by the totalitarian society, by the police and the ugly society…we do not want to be silent. Like Lu Xun said, life is ourselves: everybody is responsible for his own life. Our flesh body and our life are in exile in our homeland, until we disappear.”

Women Writers Committee gathering at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference including Chair Judy Buckrich in turquoise in center.

Women participants at the conference focused in addition on the restrictions for women writers in the region.

Qi Jiazhen was imprisoned 10 years and accused of trying to overthrow the government after she inquired whether she could study aboard. She said she had been young and inexperienced and felt guilty and wrong, the same feeling shared by other women. Gender awareness was low in China, she said. She now lives in Melbourne, Australia.

Celebrated mainland journalist Gao Yu confirmed two kinds of prisoners in China—special treatment prisoners & prisoners of conscience. As vice chief editor of an economic weekly with an international reputation, she was a special treatment prisoner. She had treatment when she was sick and had to do little hard manual work because was already 50 and given 7 years in prison. But she never admitted her wrong doing so she didn’t enjoy any pain reductions, she said.

Chinese journalist and PEN main case Gao Yu with translator.

In a panel on Censorship and Self-Censorship, Gao Yu noted that censorship began at school where children learned to protest injustice when not treated fairly. Later in life that grew into resistance of the system. The writer who sought to express truth experienced censorship which could lead to punishment and prison. But that was not as frightening as being silent, she said. The essence of being a writer was to have integrity and speak the truth.

After the conference, a dozen police picked up one participant and took him to a hotel room to find out what the conference had been about. A poet and member of ICPC, he told the police, “To build a ‘harmonious society’ and ‘harmonious culture’ [as President Hu Jintao has called for], writers should sit with writers and not always have to sit with policemen.” He was finally released after hours of interrogation.

One of the more creative campaign tools planned during the conference was spearheaded by a team of PEN Centers in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia. The members developed a digital relay with Chinese poet Shi Tao’s poem June. The poem tracked the path of the Olympic torch across a digital map. Shi Tao was serving a 10-year prison sentence for sharing with pro-democracy websites a government directive for Chinese media to downplay the 15th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests. His emails had been turned over to the Chinese government as evidence by Yahoo. His poem commemorated the Tiananmen Square massacre and was translated and read in the languages of PEN’s centers around the world, including in regional dialects as well as in the major languages. Ultimately 110 of PEN’s 145 centers participated and translated the poem into 100 languages, including Swahili, Igbo, Krio, Tsotsil, Mayan. The poem’s journey began on March 30, 2008 in Athens and traveled to every region on the online map, arriving in Hong Kong on May 2 and in June to Tibet where it was translated into Tibetan and the proposed Uyghur PEN center translated it into Uyghur. Finally August 6-8 it arrived in Beijing where it was translated and read in Mandarin. Anyone could click on the map and hear the poem in the language of the country designated.

By the 2008 Olympic Games 39 writers remained in prison in China.

June

By Shi Tao

My whole life

Will never get past ‘June’

June, when my heart died

When my poetry died

When my lover

Died in romance’s pool of blood

June, the scorching sun burns open my skin

Revealing the true nature of my wound

June, the fish swims out of the blood-red sea

Toward another place to hibernate

June, the earth shifts, the rivers fall silent

Piled up letters unable to be delivered dead.

(Translated by Chip Rolley)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 44: World Journey Beginning at Home

PEN Journey 35: Turkey Again: Global Right to Free Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN’s work attests to the power of the individual and also to a particular vision of globalization that advocates the global right to free expression, a right that supersedes national restrictions.

In February 2005 Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s most noted writers, received threats and had his books burned by nationalist groups objecting to comments he made to a Swiss magazine while he was abroad. He referred to an Armenian “genocide.” While the Armenian community rallied to defend him, their support heightened certain nationalists’ protest in Turkey. Orhan wasn’t in Turkey at the time and hoped the turmoil would die down, but a government official in southern Turkey ordered the seizing of his books from local libraries so that they could be destroyed; it turned out later that there were none of his books in those libraries.

Novelist Orhan Pamuk and Sara Whyatt, International PEN Director of Writers in Prison Committee (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At Pamuk’s request International PEN kept quiet publicly at first. In mid-April Sara Whyatt, International PEN’s Director of the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) and I had lunch with Orhan in London to discuss how PEN could help if the threat escalated. I was International Secretary of PEN at the time. We agreed that publicity at this stage could exacerbate the situation; however, we explained that PEN centers could work behind the scenes by direct contacts with their governments, and PEN would be prepared to step into public action should the need arise.

Pamuk intended to stay outside Turkey until late April/early May, but then he would be returning home to Istanbul. Sara stayed in touch with him and shared a plan for action if the threats resumed on his return. Meanwhile we told him PEN would continue to lobby for a change in the Turkish Penal Code that allowed the charges. Key PEN centers, who had good relations with their own governments, and centers from countries with influence in Turkey would make approaches. London’s WiPC would make similar approaches to Turkish officials in Ankara and also through mechanisms at the United Nations, OSCE, and the European Union (EU). At the time Turkey was hoping to become a member of the EU and was attempting to align its judiciary codes with those required by the EU. PEN also worked with the International Publishers Association .

PEN prepared a statement on the situation in Turkey from early 2005 and kept it updated with news and recommended actions for the over dozen PEN centers ready to respond on this case. There was also press guidance should the centers receive queries. Meanwhile PEN continued to work on the other cases of over 70 writers and intellectuals charged or in prison in Turkey, which had long been a country with a revolving door of writers harassed, detained, attacked and sent to prison.

On April 1, 2005 World Peace Day the Turkish press reported:

The investigation against author Orhan Pamuk due to this statement saying, ‘One million Armenians and 30,000 Kurds were killed’ [in Turkey] has ended with a case in which he is accused of violating article 301 of the new Penal Code (same as famous article 159 in the former one) “Insulting Turkish nationality” and with the demand of being imprisoned between six months and three years. The first hearing will take place at Istanbul Sisli No. 2 First Instant Criminal Court on December 16, 2005.

The Public Prosecutor claimed that Pamuk’s remarks in Switzerland’s Das Magazin were an infringement of Article 301/1 of the Turkish Penal Code which states that “the public denigration of Turkish identity” is a crime and that those found guilty should be given sentences ranging from 6-36 months.

With threats renewed by the Public Prosecutor and a lawsuit filed against Pamuk that could result in a three-year prison term, Orhan finally gave PEN the green light to launch its campaign. PEN centers mobilized globally, including in Turkey.

“It is a disturbing development when an official of the government brings criminal charges against a writer for a statement made in another country, a country where freedom of expression is allowed and protected by law,” I noted at the time.

Pamuk’s hearing in December, 2005 was approximately ten years after renowned Turkish writer Yaşar Kemal had been called to trial on similar charges in January 1995. Pamuk told a colleague he would underline two things in his statement:

1. What I said is not an insult, but the truth.

2. What if I were wrong? Right or wrong, do not people have the right to express their ideas peacefully in this Turkey?

Eugene Schoulgin, PEN International Board Member and Müge Sökmen (Turkish PEN) at WiPC Conference, Istanbul, 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the judicial hearing, PEN members came to stand witness to the proceedings, including WiPC Chair Karin Clark, Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar, and International PEN board member and former WiPC Chair Eugene Schoulgin. Armored police officers escorted Orhan as protesters hurled a barrage of eggs and jumped on the car, punching the windshield.

PEN’s observers reported at the time: “The scenes around the first appearance of Orhan Pamuk before Sisli No. 2 Court of First Instance on 16 December 2005 at 11:00 were marked by constant shouting and scuffling turning ugly and violent at times. As those attending the proceedings left the court, eggs were hurled along with insults from the nationalists and fascists among the crowd lining the pavement across the street. This in full sight of the national and international media which had turned out in full…

“The courtroom was packed with well over 70 people—among them famous Turkish writers such as Yaşar Kemal and Arif Damar, and representatives of the European Parliament, several diplomats, members of Turkish and international freedom of speech organizations. The aggression and heckling inside and outside the court did not abate…”

The session ended after an hour and 15 minutes with an adjournment because the Ministry of Justice said that it needed more time to decide on the legal basis of the trial.

Hearing the news of postponement, International PEN President Jiří Gruša declared, “It is unbelievable that Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s best known and eminent authors, is in this situation. What it indicates is a complete disregard for the right to freedom of expression not only for Pamuk, but also for the Turkish populace as a whole. This decision bodes ill for other writers who are being tried under similar laws.”

He added, “PEN demands that the trials against all writers, publishers and journalists be halted and that the laws under which they are being tried be removed from the Penal Code. We also call on the Turkish authorities to put a definitive end to the penalization of those who exercise their right to freedom of expression.”

Hrant Dink, Journalist and Editor-in-chief Argos and Hilde Keteleer (Belgian Flemish PEN) at PEN WiPC Conference in Istanbul, Spring 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the time there were 14 other writers, publishers and journalists on trial under the newly revised “insult” law for criticizing the Turkish state and its officials. These included Ragip Zarakolu, publisher of books by Armenian authors and Hrant Dink, editor of an Armenian language newspaper, who was assassinated two years later.

For Pamuk the charges were dropped in January 2006, though on a technicality rather than on legal grounds protecting freedom of expression. The widespread opposition to Pamuk’s prosecution by PEN and other organizations succeeded, but as Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar noted in The New York Times: “There are many people abroad who fail to see beyond Orhan Pamuk’s trial. Saving a writer like Orhan Pamuk from prosecution may stand as a symbolic example on its own. But it is not an overall resolution for other intellectuals and writers that still face similar charges in Turkey.”

In March 2006 Orhan was the featured guest at PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee’s biennial conference held in Istanbul, hosted by Turkish PEN.

Writers in Prison Conference Istanbul 2006. L to R: Karin Clark (International PEN Chair WiPC), Sara Whyatt (Director WiPC), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary International PEN), and Sara Wyatt (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

On October 12, 2006 Orhan Pamuk won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

It could be said that the case of Orhan Pamuk signaled a long ride to the end of Turkey’s potential membership in the EU. In September 2006 the European Parliament called for the abolition of laws such as Article 301 “which threaten Europe’s free speech norms.” In 2008, the law was reformed, but according to the reform, it remained a crime to explicitly insult the “Turkish nation” rather than “Turkishness,” and in order to open a court case based on Article 301, a prosecutor was required to have approval of the Justice Minister; a maximum punishment was reduced to two years in jail. In November 2016 the members of the European Parliament voted to suspend negotiations with Turkey over human rights and rule of law concerns. In February 2019 the European Union Parliament committee voted to suspend accession talks with Turkey.

Turkey continues to be one of the most problematic countries for writers, especially on certain topics. While Turkey’s Penal Code relaxed for a while, allowing more space and freedom for writers, in the last years, the code and its execution has grown more onerous than ever.

*****

In that spring of 2005, I attended an event celebrating Press Freedom Day (May 3), hosted by Italian PEN in Venice. There I shared testimonials from writers on whose behalf PEN had worked. I share these again here:

** Cuban journalist and poet Jorge Olivera Castillo was conditionally released from prison in December 2004 after serving 20 months of an 18-year sentence. He wrote:

Your solidarity has been a light in the darkness. Thank you for having elected me as an Honorary Member…[I send] to all of you my gratitude for your messages of support and your unflagging concern.

** Nkwazi Mhango, Tanzanian journalist in exile, wrote:

Believe it or not tears are gushing as I am writing this message. No way in whatsoever manner my family and I can reciprocate your love and commitment to our plight. THANKS AGAIN AND AGAIN AND AGAIN MORE.

** On a sadder note the following was received from Tunisian internet writer Zouhair Yahyaoui, who died suddenly in March 2005 from a heart attack after he’d been released from prison:

Your email gave me once again a lot of hope for a better future in my country at a time when the dictatorship uses all illegal and barbaric means to make us give up and abandon all forms of protest…The fact that I continue to struggle to obtain our right to freedom of expression, here in Tunisia, is thanks to support of members of International PEN and other international organizations. Thank you again to you, to the Writers in Prison committee of International PEN and to all the PEN clubs all over the world who have supported me enormously during my imprisonment and who continue to do so.

** And from Chinese writer Jiang Qisheng:

… I am not a remarkable person. I am just an ordinary guy who did something extraordinary because it was the right thing to do…If my own case has any special significance it is only that it forces people to face a highly embarrassing fact—the fact that even now, in the dawn of the 21st century, a Chinese citizen can be imprisoned for what he says.

** I ended with a passage from the book This Prison Where I Live, the collection of prison writings drawn together by International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. In the afterword Malawian poet Jack Mapanje, who himself was in prison during the autocratic rule in his country, tells how bits of news managed to get smuggled into him in his concrete cell filled with spiders and cockroaches, scorpions and bats and bat droppings.

I found the note, unusually fat…I found a bulletin of typed world news and two poems by Brecht…Pat also enclosed two honorary membership cards from International PEN’s English and American centers, issued in London and New York respectively. They each bore my name. I had been made a member of PEN. Well, well, well!…

Then there was a cutting from Britain’s Guardian newspaper. Lord Almighty! A picture of Ronald Harwood, Harold Pinter, Antonia Fraser, and other members of English PEN reading from my book of poems in protest at the Malawi High Commission in London! It must sure have an effect, I thought. Ten thousand miles away, among the cockroaches of the prison where I lived I felt utterly humbled. Shattered. Such generosity, such warmth I surely did not deserve. All for one slim volume of poems? Why hadn’t I written more poems? I was dumbstruck. Despair vanquished. ‘I am belonged,’ I heard myself whisper.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 36: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part One

PEN Journey 15: Speaking Out: Death and Life

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

As I wrote holiday cards for the prisoners on PEN’s list this year, I recalled the many cases of writers PEN has worked for over the decades—the successes when writers were released early from prison and the sorrow when they did not survive. The path back for a writer imprisoned for his work is rarely easy, at times has led to exile, but often is accompanied by a mailbag full of cards and letters from fellow writers around the world.

I also sat with PEN’s Centre to Centre newsletters spread around me from 1994-1997, the years I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). During that period if a country was mentioned, I knew whether writers were imprisoned there and often knew the main cases as did PEN’s researchers. At the time we published twice a year PEN’s list with brief descriptions of the cases. Proofing paragraph after paragraph of hundreds of situations, I would know without looking when I had moved from one country to another by the punishments given. Lengthy prison terms up to 20 years to life meant I was reading cases from China, but if the writers were suddenly killed either by government or others, I’d moved on to Columbia. In Turkey were pages and pages of arbitrary detentions and investigations and writers rotating in and out of prison.

Names from this period are a kind of ghost family for me, evoking people and a time and place: Taslima Nasrin, Fikret Başkaya, Mohamed Nasheed, Gao Yu, Bao Tong, Hwang Dae-Kwon, Myrna Mack, Ma Thida, Yndamiro Restano, Mansur Rajih, Luis Grave de Peralta, Brigadier General José Gallardo Rodríguez, Koigi wa Wamwere, Eskinder Nega, Tefera Asmare, Liao Yiwu, Ferhat Tepe, Dr. Haluk Gerger, Ayşe Nur Zarakolu, Ünsal Öztürk, İsmail Beşikçi, Eşber Yağmurdereli, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Đoàn Viết Hoạt, Nguyễn Văn Thuận, Balqis Hafez Fadhil, Tong Yi, Christine Anyanwu, Tahar Djaout, Aung San Suu Kyi, Yaşar Kemal, Alexander Nikitin, Faraj Sarkohi, Ali Sa’idi Sirjani, Wei Jingsheng, Chen Ziming, Slavamir Adamovich, Bülent Balta, and many more. Many are now released, a few are even working with PEN, a number have deceased and two of the most celebrated and tragic—Liu Xiaobo and Ken Saro-Wiwa—were executed, one left to die in prison, the other hung.

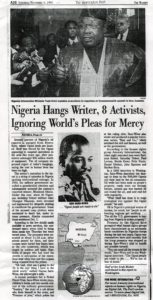

Page 1 of PEN International’s campaign for Ken Saro-Wiwa 1994-1996

In their cases, no amount of mail or faxes or later emails or personal meetings with ambassadors and diplomats changed the course for these writers. A year before Ken Saro-Wiwa’s death, noted Iranian novelist Ali Sa’idi Sirjani died in prison. And years later the murder of Anna Politkovskaya in Russia and the murder of Hrant Dink in Turkey and in 2017 the death in prison of Chinese poet and Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo all stand out as main cases where PEN and others organized globally but were unable to change the course. I’ll address the case of Liu Xiaobo in a subsequent blog. He was also in prison during the 1990’s but was not yet the global name and force he became.

One of the most noted of PEN’s cases in the mid 1990s was Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa who was hanged November 10, 1995. Ken understood they would hang him, but PEN members did not accept this. Ken was an award-winning playwright, television producer and environmental activist who took on the government of Nigerian President Sani Abacha and Shell Oil on behalf of the Ogoni people whose land was rich in oil and also in pollution and whose people received little of the profits.

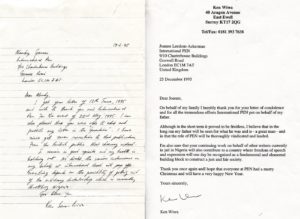

I was living in London when Ken Saro-Wiwa, who had been arrested before for his writing and activism, visited PEN and other organizations in support of the Ogoni cause. PEN took no position on political causes but campaigned for his freedom to write and speak without threat. He met at length with PEN’s researcher Mandy Garner, providing her books and documentation of how he was being harassed in case he was arrested again. When he returned to Nigeria, he was arrested again and imprisoned in May 1994, along with eight others, and charged with masterminding the murder of Ogoni chiefs who were killed in a crowd at a pro-government meeting. The charge carried the death penalty.

PEN mobilized quickly and stayed in close contact with his family. Mandy worked tirelessly on the case, gathering and coordinating information and actions. Ken Saro-Wiwa was an honorary member of PEN centers in the US, England, Canada, Kenya, South Africa, Netherlands, and Sweden so these centers were particularly active, contacting their diplomats and government officials. At PEN International we met with members of the Nigeria High Commission; novelist William Boyd joined the delegation. “I remember sitting opposite all these guys in sunglasses wearing Rolex watches, spouting the government line,” Mandy recalls. We also talked with ambassadors, including from England, the US and Norway to encourage their petitioning of the Abacha government. We met with Shell Oil officials to ask that they intervene to save Ken Saro-Wiwa’s life. PEN USA West also had lengthy meetings and negotiations with Shell Oil. PEN International and English PEN set up meetings in the British Parliament where celebrated writers spoke. English PEN mounted candlelight vigils outside the Nigerian High Commission which writers including Wole Soyinka, Ben Okri, Harold Pinter, Margaret Drabble and International PEN President Ronald Harwood attended. A theater event in London featured Nigerian actors acting out extracts from Ken’s plays and also reading poems from other writers in prison. Taslima Nasreen spoke as well. Ken’s writing was made available to the press which covered the story widely.

Poem from Malawian poet Jack Mapanje to Ken Saro-Wiwa published on page 2 of PEN Campaign document above

The activity in London mirrored activity at PEN’s more than 100 centers around the globe, from New Zealand to Norway, from Malawi to Mexico. From every continent signed petitions were faxed to the Nigerian government of General Sani Abacha and to the writers’ own governments, to members of Commonwealth nations, to the European Union, the United Nations and to the press calling for clemency for Ken Saro-Wiwa. Through the International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) of which PEN International was a founding member, the word spread to freedom of expression organizations worldwide. Other human rights organizations including Amnesty and Greenpeace also protested. No one wanted to believe in the face of such an international outcry that the generals in Nigeria, particularly Nigeria’s President Sani Abacha, would kill Ken Saro-Wiwa.

Ken managed to get word out that he was tortured and held in leg irons for long periods of time. He wrote to Mandy, “A year is gone since I was rudely roused from my bed and clamped into detention. Sixty-five days in chains, many weeks of starvation, months of mental torture and, recently, the rides in steaming, airless Black Maria to appear before a Kangaroo court, dubbed a Special Military Tribunal where the proceedings leave no doubt at all that the judgement has been written in advance. And a sentence of death against which there is no appeal is a certainty.”

I moved from London to Washington, DC in late August 1995. When the death sentence was handed down at the end of October, PEN International launched a petition signed by hundreds of writers from around the globe seeking Saro-Wiwa’s and others’ release. For days I tried to get an appointment with the Nigerian Ambassador in Washington. Finally one morning I received a call that I had been given an appointment; however, I was in New York City that morning. Quickly I got a flight back to Washington. En route I called the former PEN WiPC director Siobhan Dowd, who was then heading the Freedom to Write program at American PEN. I asked her to arrange for a second writer to meet me at the Nigerian Embassy. The person didn’t have to say anything, but I wanted a larger delegation.

When I arrived, I was informed the Ambassador had suddenly been called to the U.N. in New York so I met with the number two and three ministers. As I began setting out PEN’s case on behalf of Saro-Wiwa, another woman slipped into the room and sat without speaking but lending ballast to the meeting. Afterwards she and I had coffee, and I briefed her on the case. For the next 25 years Susan Shreve, one of the founders of the PEN Faulkner Foundation, and I have been friends, a friendship that grew out of this tragic event. A few days later I was standing outside the Nigerian Embassy in a vigil, along with representatives from Amnesty and other organizations, when word was sent out to us that Ken Saro-Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt.

Article from The Washington Post November 11, 1995

The effect of his execution raced through the PEN network and through the human rights and political communities worldwide. The grief was communal. Those who worked on Ken’s case can relate to this day where they were when they heard the news of the execution. The shock was also political. Boycotts were launched against Nigeria. Archbishop Desmond Tutu appeared at a benefit in London for Ken Saro-Wiwa and reported outrage in South Africa over the executions of Saro-Wiwa and the others. He said South African President Nelson Mandela was heading up a campaign to urge the world, especially the US and Western governments to take action. Nigeria was suspended from the British Commonwealth for three years.

Ken’s brother quickly left Nigeria and went to London for a period, sheltering temporarily with British novelist Doris Lessing then relocated in Canada for a time. Ken Saro-Wiwa’s son, Ken Saro-Wiwa Jr., a journalist, also settled in Canada, then in London, then returned and worked for a period in the Nigerian government of Goodluck Jonathan as a special assistant on civil society and international media. He died suddenly in London at age 47 in 2016.

Letter on left from Ken Saro-Wiwa to PEN researcher Mandy Garner. Letter on right from Ken Saro-Wiwa, Jr. to WiPC Chair Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

The killing of Ken Saro-Wiwa was the beginning of the end for General Sani Abacha, who maneuvered to be the sole presidential candidate in Nigeria’s next election, but died in June, 1998 when he suddenly got ill early one morning and died within two hours, at age 54, the same age as Ken Saro-Wiwa when he was hanged. There were persistent rumors that Abacha had been poisoned, but there was no autopsy and these rumors were never proven.

According to news reports in Lagos, it took five attempts to hang Ken Saro-Wiwa. He was buried by security forces, denying his family the right to bury him. His last words were reported to be: “Lord, take my soul, but the struggle continues.”

Releases of writers PEN worked for that year included Cuban poet Yndamiro Restano freed after serving three years of a ten-year sentence, Cuban journalist Pablo Reyes Martinez freed after three years on an eight-year sentence, Turkish writer Fikret Baskaya freed early and also Unsal Ozturk, freed eight years early, Chinese writer Yang Zhou freed after serving one year of a three-year sentence and Wang Juntao freed after serving five years of a 13-year sentence, Burmese Zargana freed a year early and many others.

“I wish to thank International PEN and the WiPC for all their endeavors on my behalf during the period of my detention. There is no doubt in my mind at all that the powerful insistence and impartial voice of PEN did a lot to win me my freedom from the tyrannical arms of the military dictatorship in Nigeria…”—Ken Saro-Wiwa in fall, 1993 after his earlier detention.

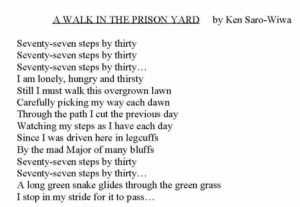

From Ken Saro-Wiwa’s poem “A Walk in the Prison Yard”

Next Installment: PEN Journey 16: The Universal, the Relative and the Changing PEN