Posts Tagged ‘Ken Saro Wiwa’

PEN Journey 37: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part Two

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

At PEN’s 71st World Congress in June 2005 over 275 writers from 88 PEN Centers gathered from around the world in the idyllic setting of Bled, Slovenia where history had been made 40 years before. In 1965, PEN had held its Congress in Bled, the first in Eastern Europe since the Second World War. Russian writers visited PEN for the first time. At that 33rd World Congress, American playwright Arthur Miller, who’d recently passed away in 2005, had been elected the first and only American President of International PEN.

Lake Bled in Bled, Slovenia, site of PEN International’s 71st World Congress, 2005

In 2005 the global dynamics had changed. PEN now had active centers in most of the countries in the former Communist Eastern bloc, including in Russia. The European Union (EU) was in its ascendancy; 2005 marked Slovenia’s accession into the EU. Globalization was bringing benefits but also threats to the cultures of smaller countries.

Reception 71st PEN Congress in Bled, 2005. L to R: Frank Asare Donkoh (Ghana PEN), Jane Spender (Program Director PEN International), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Secretary), Alfred Msadala (Malawi PEN), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (PEN Executive Director), Dan Khayana (Uganda PEN), Bao Viet Nguyen-Hoang (Suisse Romand PEN) [Photo credit for many photos: Tran Vu]

“We live in an age when many preconceived ideas, nurtured for centuries and ostensibly immutable, are no longer valid,” noted Slovene PEN President Tone Peršak. “The linguistic and cultural image of the world is in flux and civilization as a whole, under the influence of globalization, is taking on a new character. These events are also echoed in discussions within PEN centers…They guided us in our selection of the main topic for discussion at the Congress, namely the issue of linguistic and consequently cultural diversity of the world. The topic is proposed as a question: does linguistic diversity stimulate or hinder cultural development? Is it a curse or a blessing that made possible the emergence and encounter of various world views, different emotional responses to the human destiny, and finally also brought about the formulation of different schools of thought and philosophical doctrines?

“We regard the question of linguistic and cultural diversity also as a human rights issue. Attempts to unify and subject all aspects of life to uniform standards and norms is viewed as a very questionable encroachment on these rights. One of the topics is therefore the question of the need to protect languages and cultures, and that means also the smallest ones which may be on the verge of extinction. Let us also draw your attention to literature’s role in the preservation of the memory of the cultural landscape, which has been undergoing considerable changes and in some cases may even disappear forever…[Is] literature a kind of lingua franca which could and should contribute to a better mutual understanding and insight into the different cultures and nations that sustain cultural diversity?”

These were questions without definitive answers, but questions that occupied writers from dozens of cultures and languages in the Congress’s literary sessions. [At PEN Congresses, the main sessions and the Assembly of Delegates were usually translated into PEN’s three official languages—English, French and Spanish—and also the language of the Congress host.]

PEN International Congress Bled, Slovenia 2005. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Monika Van Paemel (Belgium (Dutch-speaking) PEN), Alexander Blokh (French PEN and former PEN International Secretary), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Jiří Gruša (President, International PEN)

A number of the delegates had before been to Bled, home of PEN International’s annual Writers for Peace Committee conference, hosted by Slovene PEN. During the Cold War the Peace Committee, founded in 1984, provided one of the only open forums for dialogue between writers from the East and West.

“Let us learn the language of our neighbors so that we all may better come to know and understand our neighbors and forestall incomprehension and conflict,” the Peace Committee and the Congress organizers urged.

In my own address to the Congress as International Secretary, I relied on the prevailing metaphor of the bridge, using an example close to home:

I recently crossed a soaring new bridge in Boston, Massachusetts, a bridge at least 14-years in the making. This bridge spanning the Charles River was the result of what is called the Big Dig, a project anyone who has lived in or regularly visited Boston has come to think of as the Eternal Dig for it is hard to remember when a large segment of downtown wasn’t under construction. But at last there is this soaring bridge with stanchions into the sky in gracious arcs and at night a blue light shining up into its cables as it rises above the city. There is also an elaborate network of freeways and tunnels underground.

I sometimes think International PEN is a bit like the Big Dig. For much of the last decade we’ve been reconstructing ourselves, trying to reflect in our governing structures the expansion that PEN has experienced across the globe, an expansion brought on in part by the opening up of societies after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the lifting of the so-called Iron Curtain. This expansion has also been enabled by the linking of the globe through the internet. International PEN has instituted a Board, been through a long range planning process, revised rules and regulations, and while we still have construction going on and probably always will, I’m hopeful that we too will start to see more and more of the benefits of all this work…Throughout we’ve continued to witness remarkable activities from our Centers…

This year I’ve been telling people that PEN is a place where cultures don’t clash but communicate. PEN members may not always agree, in fact frequently don’t agree, but the fellowship among members can keep that disagreement from turning into confrontation. At our best PEN’s forums offer a place where the energy of competing ideas releases light, rather like that spectacular blue light which shoots upwards on the cables of the grand bridge in Boston.

Arthur Miller once described PEN: “With all its flounderings and failings and mistaken acts, it is still, I think, a fellowship moved by the hope that one day the work it tries and often manages to do will no longer be necessary. Needless to add, we shall need extraordinarily long lives to see that noble day. Meanwhile we have PEN, this fellowship bequeathed on us by several generations of writers for whom their own success and fame were simply not enough.”

The work included substance and form, the latter focusing on the organizational structure which allowed the work to go forward. At the Bled Congress the delegates approved procedural reforms, broke into workshops to discuss PEN itself and global and regional issues, and were introduced to PEN’s first Executive Director, who would begin the following month. After an extensive search, the board and staff had agreed to hire Caroline Whitaker (née McCormick) who had worked in theater development, had a degree in literature and was coming to PEN from the Natural History Museum where she was Director of Development.

Writers in Prison Committee and Workshop Sessions, PEN International Congress, Bled, Slovenia, June 2005

At the Congress seven candidates from Algeria, Colombia, Croatia, France, Finland, Japan, and Russia ran for positions on the International Board, and Mohamed Magani (Algerian PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), and Takeaki Hori (Japan PEN) were elected.

The Congress discussed and passed over 20 resolutions and actions challenging the situations for writers in Algeria, Basque region of Spain, Belarus, Burma, China, Cuba, Iran, Maldives, Mexico, Nepal, Russia, Syria, Tibet, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam as well as resolutions relating to the attacks on journalists in war zones and the crackdown on internet writing in Tunisia where the World Summit on the Information Society was to be held that fall.

The Congress also noted the tenth anniversary of the death of PEN member Nigerian writer Ken Saro-Wiwa. International PEN President Jiří Gruša noted: “We are living in a time of extraordinary threats to writers and the freedom to write. In the ten years since our colleague Ken Saro-Wiwa was executed in Nigeria, hundreds of writers and journalists around the world have died by violence. Crackdowns on internet writers and anti-terrorism legislation have named writers and chilled freedom of expression in a number of countries.

“While our colleagues in countries such as Myanmar, Cuba, China and Belarus continue to struggle against conventional governmental censorship and repression, writers also face the threat of moral violence in countries from Mexico to Iraq and new pressures associated with writing and publishing on the internet.”

Among the guests at the Congress were Colin Channer, who introduced the prospective Jamaica PEN Center which was voted into PEN at the subsequent 2006 Congress in Berlin.

And for the first time since the Tiananmen Square massacre June 4, 1989, a writer from the People’s Republic of China attended as a representative of the new Independent Chinese PEN Center whose members included writers from inside and outside of mainland China. I include below much of his talk which rings truer than ever.

Wang Yi* addressed the Assembly, noting that this was the first time in 16 years “the voice of a non-official and independent Chinese writers’ group could be heard, a group that is independent or at least strives for its independence, that is free or at least longs for freedom and that tries to perpetuate the freedom of expression in the face of great political pressure…

Wang Yi (Independent Chinese PEN Center)

“I come here heavy-hearted without blessing, because there is no reconciliation between a free writer, an independent intellectual, and his government. I come to Bled representing those who have been disgraced, who have stood in the shadow of terror and the peril of political oppression, and who have yet never resigned but have insisted upon their freedom of speech and writing, such as Mr. Liu Xiaobo whose work has been not allowed to be published and who has not been allowed to go abroad. I also come for myself, who experienced in the sixteen years after Tiananmen a long period during which memories have been erased forcefully and silence has been ordered. This has been a time during which mothers, who lost their sons and daughters at Tiananmen, have not been allowed to weep…

“To me and my colleagues, writing is a rescue plan for the hostage. Writing means dignity and freedom; it is kind of belief. But we cannot rescue ourselves, even when we have courage and when justice is on our side in the face of institutional arbitrariness…

“Our salvation depends upon that higher community, depends upon common universal values that we share as writers, as free people and as intellectuals. It is the source of liberty and imagination…

“We are disappointed to see that some European governments are gradually abandoning free values and lessening their criticism of the despotic regime in Beijing. For a common benefit they abandon the writers, reporters, dissidents and orators who are imprisoned…

“According to the Independent Chinese PEN club, more than 50 writers and reporters are currently in jail…

“I want to mention two points: the first one is the belief that through writing, we can enlighten and preserve basic human values. Second, there is a global realistic linguistic environment. These two points make me think that the persecution of Chinese, Tibetan, Uighur and other minority writers reaches across borders to become an international issue…There is only the suppression of the right to freedom of expression and the persecution of human beings, which needs to be rooted out, and the victim needs to be consoled and supported…

“The Chinese government’s suppression of writers has accelerated in recent years, since the beginning of the Internet era…pen names and pseudonyms are prohibited. With this act, the last bastion of self-protection is destroyed.

“Every morning, the Communist Party’s propaganda department issues a list of prohibited news to the media. Whoever dares to break the taboos will get into big trouble. As the government stifles the mouths of the media and betrays the public, it also tampers with the truth in historical textbooks and deceives the children in school. An increasing number of courageous writers, reporters and public figures are daring to challenge the status quo so more and more of them have been thrown into jail on charges of committing the crime of “instigation and subversion of the state” or “disclosing state secrets” to “hostile forces…

Liu Xiaobo and Yu Jie (Independent Chinese PEN Center)

“Among the harassed and persecuted are also the president of ICPC and his deputy, Mr. Liu Xiaobo* and Mr. Yu Jie*. Under such circumstances, you cannot but regard the Chinese writer as a hostage…

“I come to Bled hoping to present myself as a writer, but I am indeed only a hostage…One of the reasons that I definitely wanted to come is that I believe we all belong to the same world. In this world, the state, the glory and the lawful right all belong to that higher spiritual origin that makes us, without regret, proud to be a writer.”

*[Wang Yi, deputy Secretary General of ICPC 2003-2007, has been imprisoned in China since December 2018, serving a 9-year sentence for “activities disobedient to the government control” and “inciting subversion of state power and illegal business.” Wang Yi is a writer and a Christian pastor. Liu Xiaobo, the second President of ICPC, was sentenced in December 2008 to an 11-year prison sentence as “an enemy of the state” for “incitement of subverting state power.” He was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in custody June 13, 2017. Yu Jie, a celebrated writer, was one of the drafters, along with Liu Xiaobo, of Charter 08, which set out a democratic vision for China; he was arrested and tortured in 2010 and immigrated to the U.S. in 2012. He is author of Steel Gate to Freedom: The Life of Liu Xiaobo.]

Lake Bled, Slovenia, site of PEN International 71st World Congress, 2005

Next Installment: PEN Journey 38: PEN’s Work On the Road in Kyrgyzstan and Ghana

PEN Journey 15: Speaking Out: Death and Life

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

As I wrote holiday cards for the prisoners on PEN’s list this year, I recalled the many cases of writers PEN has worked for over the decades—the successes when writers were released early from prison and the sorrow when they did not survive. The path back for a writer imprisoned for his work is rarely easy, at times has led to exile, but often is accompanied by a mailbag full of cards and letters from fellow writers around the world.

I also sat with PEN’s Centre to Centre newsletters spread around me from 1994-1997, the years I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). During that period if a country was mentioned, I knew whether writers were imprisoned there and often knew the main cases as did PEN’s researchers. At the time we published twice a year PEN’s list with brief descriptions of the cases. Proofing paragraph after paragraph of hundreds of situations, I would know without looking when I had moved from one country to another by the punishments given. Lengthy prison terms up to 20 years to life meant I was reading cases from China, but if the writers were suddenly killed either by government or others, I’d moved on to Columbia. In Turkey were pages and pages of arbitrary detentions and investigations and writers rotating in and out of prison.

Names from this period are a kind of ghost family for me, evoking people and a time and place: Taslima Nasrin, Fikret Başkaya, Mohamed Nasheed, Gao Yu, Bao Tong, Hwang Dae-Kwon, Myrna Mack, Ma Thida, Yndamiro Restano, Mansur Rajih, Luis Grave de Peralta, Brigadier General José Gallardo Rodríguez, Koigi wa Wamwere, Eskinder Nega, Tefera Asmare, Liao Yiwu, Ferhat Tepe, Dr. Haluk Gerger, Ayşe Nur Zarakolu, Ünsal Öztürk, İsmail Beşikçi, Eşber Yağmurdereli, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Đoàn Viết Hoạt, Nguyễn Văn Thuận, Balqis Hafez Fadhil, Tong Yi, Christine Anyanwu, Tahar Djaout, Aung San Suu Kyi, Yaşar Kemal, Alexander Nikitin, Faraj Sarkohi, Ali Sa’idi Sirjani, Wei Jingsheng, Chen Ziming, Slavamir Adamovich, Bülent Balta, and many more. Many are now released, a few are even working with PEN, a number have deceased and two of the most celebrated and tragic—Liu Xiaobo and Ken Saro-Wiwa—were executed, one left to die in prison, the other hung.

Page 1 of PEN International’s campaign for Ken Saro-Wiwa 1994-1996

In their cases, no amount of mail or faxes or later emails or personal meetings with ambassadors and diplomats changed the course for these writers. A year before Ken Saro-Wiwa’s death, noted Iranian novelist Ali Sa’idi Sirjani died in prison. And years later the murder of Anna Politkovskaya in Russia and the murder of Hrant Dink in Turkey and in 2017 the death in prison of Chinese poet and Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo all stand out as main cases where PEN and others organized globally but were unable to change the course. I’ll address the case of Liu Xiaobo in a subsequent blog. He was also in prison during the 1990’s but was not yet the global name and force he became.

One of the most noted of PEN’s cases in the mid 1990s was Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa who was hanged November 10, 1995. Ken understood they would hang him, but PEN members did not accept this. Ken was an award-winning playwright, television producer and environmental activist who took on the government of Nigerian President Sani Abacha and Shell Oil on behalf of the Ogoni people whose land was rich in oil and also in pollution and whose people received little of the profits.

I was living in London when Ken Saro-Wiwa, who had been arrested before for his writing and activism, visited PEN and other organizations in support of the Ogoni cause. PEN took no position on political causes but campaigned for his freedom to write and speak without threat. He met at length with PEN’s researcher Mandy Garner, providing her books and documentation of how he was being harassed in case he was arrested again. When he returned to Nigeria, he was arrested again and imprisoned in May 1994, along with eight others, and charged with masterminding the murder of Ogoni chiefs who were killed in a crowd at a pro-government meeting. The charge carried the death penalty.

PEN mobilized quickly and stayed in close contact with his family. Mandy worked tirelessly on the case, gathering and coordinating information and actions. Ken Saro-Wiwa was an honorary member of PEN centers in the US, England, Canada, Kenya, South Africa, Netherlands, and Sweden so these centers were particularly active, contacting their diplomats and government officials. At PEN International we met with members of the Nigeria High Commission; novelist William Boyd joined the delegation. “I remember sitting opposite all these guys in sunglasses wearing Rolex watches, spouting the government line,” Mandy recalls. We also talked with ambassadors, including from England, the US and Norway to encourage their petitioning of the Abacha government. We met with Shell Oil officials to ask that they intervene to save Ken Saro-Wiwa’s life. PEN USA West also had lengthy meetings and negotiations with Shell Oil. PEN International and English PEN set up meetings in the British Parliament where celebrated writers spoke. English PEN mounted candlelight vigils outside the Nigerian High Commission which writers including Wole Soyinka, Ben Okri, Harold Pinter, Margaret Drabble and International PEN President Ronald Harwood attended. A theater event in London featured Nigerian actors acting out extracts from Ken’s plays and also reading poems from other writers in prison. Taslima Nasreen spoke as well. Ken’s writing was made available to the press which covered the story widely.

Poem from Malawian poet Jack Mapanje to Ken Saro-Wiwa published on page 2 of PEN Campaign document above

The activity in London mirrored activity at PEN’s more than 100 centers around the globe, from New Zealand to Norway, from Malawi to Mexico. From every continent signed petitions were faxed to the Nigerian government of General Sani Abacha and to the writers’ own governments, to members of Commonwealth nations, to the European Union, the United Nations and to the press calling for clemency for Ken Saro-Wiwa. Through the International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) of which PEN International was a founding member, the word spread to freedom of expression organizations worldwide. Other human rights organizations including Amnesty and Greenpeace also protested. No one wanted to believe in the face of such an international outcry that the generals in Nigeria, particularly Nigeria’s President Sani Abacha, would kill Ken Saro-Wiwa.

Ken managed to get word out that he was tortured and held in leg irons for long periods of time. He wrote to Mandy, “A year is gone since I was rudely roused from my bed and clamped into detention. Sixty-five days in chains, many weeks of starvation, months of mental torture and, recently, the rides in steaming, airless Black Maria to appear before a Kangaroo court, dubbed a Special Military Tribunal where the proceedings leave no doubt at all that the judgement has been written in advance. And a sentence of death against which there is no appeal is a certainty.”

I moved from London to Washington, DC in late August 1995. When the death sentence was handed down at the end of October, PEN International launched a petition signed by hundreds of writers from around the globe seeking Saro-Wiwa’s and others’ release. For days I tried to get an appointment with the Nigerian Ambassador in Washington. Finally one morning I received a call that I had been given an appointment; however, I was in New York City that morning. Quickly I got a flight back to Washington. En route I called the former PEN WiPC director Siobhan Dowd, who was then heading the Freedom to Write program at American PEN. I asked her to arrange for a second writer to meet me at the Nigerian Embassy. The person didn’t have to say anything, but I wanted a larger delegation.

When I arrived, I was informed the Ambassador had suddenly been called to the U.N. in New York so I met with the number two and three ministers. As I began setting out PEN’s case on behalf of Saro-Wiwa, another woman slipped into the room and sat without speaking but lending ballast to the meeting. Afterwards she and I had coffee, and I briefed her on the case. For the next 25 years Susan Shreve, one of the founders of the PEN Faulkner Foundation, and I have been friends, a friendship that grew out of this tragic event. A few days later I was standing outside the Nigerian Embassy in a vigil, along with representatives from Amnesty and other organizations, when word was sent out to us that Ken Saro-Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt.

Article from The Washington Post November 11, 1995

The effect of his execution raced through the PEN network and through the human rights and political communities worldwide. The grief was communal. Those who worked on Ken’s case can relate to this day where they were when they heard the news of the execution. The shock was also political. Boycotts were launched against Nigeria. Archbishop Desmond Tutu appeared at a benefit in London for Ken Saro-Wiwa and reported outrage in South Africa over the executions of Saro-Wiwa and the others. He said South African President Nelson Mandela was heading up a campaign to urge the world, especially the US and Western governments to take action. Nigeria was suspended from the British Commonwealth for three years.

Ken’s brother quickly left Nigeria and went to London for a period, sheltering temporarily with British novelist Doris Lessing then relocated in Canada for a time. Ken Saro-Wiwa’s son, Ken Saro-Wiwa Jr., a journalist, also settled in Canada, then in London, then returned and worked for a period in the Nigerian government of Goodluck Jonathan as a special assistant on civil society and international media. He died suddenly in London at age 47 in 2016.

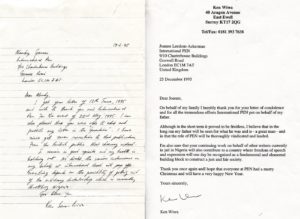

Letter on left from Ken Saro-Wiwa to PEN researcher Mandy Garner. Letter on right from Ken Saro-Wiwa, Jr. to WiPC Chair Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

The killing of Ken Saro-Wiwa was the beginning of the end for General Sani Abacha, who maneuvered to be the sole presidential candidate in Nigeria’s next election, but died in June, 1998 when he suddenly got ill early one morning and died within two hours, at age 54, the same age as Ken Saro-Wiwa when he was hanged. There were persistent rumors that Abacha had been poisoned, but there was no autopsy and these rumors were never proven.

According to news reports in Lagos, it took five attempts to hang Ken Saro-Wiwa. He was buried by security forces, denying his family the right to bury him. His last words were reported to be: “Lord, take my soul, but the struggle continues.”

Releases of writers PEN worked for that year included Cuban poet Yndamiro Restano freed after serving three years of a ten-year sentence, Cuban journalist Pablo Reyes Martinez freed after three years on an eight-year sentence, Turkish writer Fikret Baskaya freed early and also Unsal Ozturk, freed eight years early, Chinese writer Yang Zhou freed after serving one year of a three-year sentence and Wang Juntao freed after serving five years of a 13-year sentence, Burmese Zargana freed a year early and many others.

“I wish to thank International PEN and the WiPC for all their endeavors on my behalf during the period of my detention. There is no doubt in my mind at all that the powerful insistence and impartial voice of PEN did a lot to win me my freedom from the tyrannical arms of the military dictatorship in Nigeria…”—Ken Saro-Wiwa in fall, 1993 after his earlier detention.

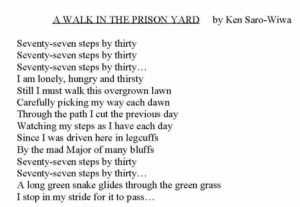

From Ken Saro-Wiwa’s poem “A Walk in the Prison Yard”

Next Installment: PEN Journey 16: The Universal, the Relative and the Changing PEN

PEN Journey 1: Engagement

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. As Vice President Emeritus of PEN International and former International Secretary, former Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, former President of PEN Center USA West, board member and Vice President of PEN America and the PEN/Faulkner Foundation, I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down some of the memories. I will try in digestible portions to recount moments, though I’m not certain how easily I can contain all these. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of some interest.

February 13, 1989: I was President of PEN Center USA West and on an airplane when I read that Salman Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses was being burned in Birmingham. The next day a fatwa was issued on Rushdie. What was a fatwa, we all asked at the time, as we, along with PEN Centers around the world, mobilized to protest that a head of state was ordering the murder of a writer wherever he was in the world.

November 10, 1995: As Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, I was standing vigil with others outside the Nigerian Embassy in Washington, D.C. when word spread that novelist and activist Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

October 7, 2006: My phone rang at 7:30 on Saturday morning. I was International Secretary of PEN International, and the International Writers in Prison Program Director was calling to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya had just been shot and killed in Moscow. We all knew Anna—I’d last had coffee with her at an airport in Macedonia. We worked with her on the situation of writers in Russia and Chechnya and had enormous respect for her knowledge and courage.

January 19, 2007: We were about to begin a PEN International board meeting in Vienna when a call came from Istanbul. Hrant Dink had just been shot and killed outside his newspaper office in Istanbul. Dink was an editor of an Armenian paper and a writer whom members of PEN knew well and worked with on freedom of expression issues in Turkey.

Most writers long active in PEN’s freedom-to-write work can tell you where they were when the news broke on each of these cases. They can tell you because the lives of these writers and many others have been critical in the struggle for freedom of expression around the world.

In sharing memories of PEN, I begin with the writers and with the many friends around the globe who work on behalf of writers who don’t have the freedom to write without threat, imprisonment or death. As colleagues, we are bound together by the belief that truthful writing matters, be it journalism, fiction, poetry, drama, essays because stories and witnessing and creative imagination connect, inspire and shape us. Free expression is fundamental to a free society and is worth defending and expanding.

Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro Wiwa, Anna Politkovskaya, Hrant Dink

My own thirty plus years working with PEN began at a dinner meeting in Los Angeles in the early 1980’s. I was a young writer, new mother, former journalist who’d recently moved across the country from New York City where I taught writing at university and had friends and colleagues. I landed in the land of sun and Hollywood, and though I had a new college teaching job, I knew few people and even fewer writers. Like many who first seek out PEN, I came for the community.

My second meeting was at someone’s home where a presentation was made about writers in different parts of the world who were in prison because of their writing. I was introduced to PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. At that meeting, we wrote postcards urging the Chinese government to release Wei Jingsheng, a writer who was imprisoned for “counterrevolutionary” activities, particularly for his essay “The Fifth Modernization” which he’d posted on the Democracy Wall in Beijing in 1978. His manifesto argued that as China was modernizing with four principles of modernization, it needed to include a fifth modernization–Democracy.

As I learned about Wei Jingsheng and the other writers on whose behalf PEN worked, I became more active in the PEN Center on the West Coast of America called PEN Los Angeles Center. I was elected President in 1988. Shortly after the election, I attended my second PEN International Congress in Seoul, South Korea right before the Olympics there. (The first Congress I attended was in 1986 in New York City, where our Center’s members were registered with the foreign delegates. I was active at that New York Congress in the Women’s revolution and the statement that came from the Congress.)

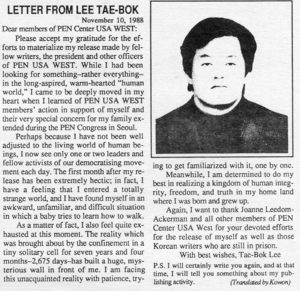

I arrived in Seoul late summer,1988 with our Center’s support for resolutions including one calling for the release of Wei Jingsheng and other writers in China, another resolution addressing writers in prison in South Korea, including our honorary member, publisher Lee Tae-Bok, and a resolution to change the name of PEN Los Angeles Center to PEN Center USA West. The name change had been passed by our center’s previous board but needed approval of the international Assembly of Delegates. It reflected our wider membership in the western part of the United States.

As president of PEN Los Angeles Center, I arrived as a young writer with a small delegation from Southern California, which included the former book editor of The Los Angeles Times and an English professor from UCLA. American PEN, based in New York, the largest of PEN’s more than 60 worldwide centers at the time was headed by Susan Sontag, president. American PEN didn’t want us to change our name and opposed our resolution on the floor of the Congress. While our two centers agreed on the other substantive issues of the Congress, including the problematic situation for writers in South Korea, and though we shared meals, the American PEN delegation, and Susan Sontag in particular, tried to get us to withdraw our name change, including a midnight call to me from Susan. The name change would be confusing, she said, and would take from the national scope of American PEN’s work. In that midnight call I listened to the arguments, then shared our thinking, which included the observation that our membership already came from many states west of the Mississippi, that in a country the size of the United States, PEN allowed more than one center, and for writers 3000 miles from New York, there was value in having more than one center of gravity. In the morning I presented American PEN’s arguments to my delegation, and we decided to go ahead and let our resolution go to the floor of the Assembly.

The representative from East Berlin noted: It would seem the East and West of America get along worse than the East and West of Germany. PEN Los Angeles Center’s resolution for a name change won by a wide margin, and we left the Congress as PEN Center USA West, which years later became PEN USA. I no longer live in Los Angeles but note that only in the past year –2018—did the members of the West Coast PEN decided to merge with PEN America in New York so there is now only one center of PEN in the US.

Most memorable and significant from the Seoul Congress was our delegation’s visit with the family of Lee Tae-Bok, our honorary member. “The house of Lee Tae-Bok’s parents is neat and spare, bedrooms with tatami mats on the floor, a living room with a sofa, a chair, a fish tank. There is no excess in the house, one senses out of choice. But there is an absence, not out of choice, for Lee Tae-Bok has been away in prison seven years. His mother worries that she will not see her oldest son out of prison before she dies,” I wrote in our Center’s newsletter. The family said that Lee Tae-Bok was in poor health and held in a cell four by five square meters, allowed out in the fresh air for only twenty minutes a day and wasn’t allowed to write except one letter a month to his family. His mother lamented the “hypocrisy” of the Korean government which had sentenced her son to life in prison because they said he published communist propaganda and yet they were greeting writers and “honored guests” at PEN’s Congress from Communist countries as well as inviting Eastern bloc athletes to Korea for the Olympic Games.

Digby Diehl and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman meet with the family of Lee Tae-Bok at the Lee home in Seoul in 1988.

In addition to our family visit, PEN Congress delegates petitioned the South Korean government on behalf of those in prison. A delegation from PEN International visited two of the writers in prison.

A few weeks after the Congress, notification reached us that Lee Tae-Bok had been released, though not everyone PEN spoke up for was released. I still remember where I was—I was in New York—when I heard the news, and I remember the elation. Many people worked on Lee Tae-Bok’s behalf so we couldn’t and didn’t take the credit, but we could feel some part of our actions, some push at the prison door helped spring it open. Release is not always the outcome for PEN’s work, but often it is. It is one of the goals. Over all my years in PEN, the release of a writer from prison still evokes a burst of hope and a measure of faith.

[Next installments: the watershed year 1988-1989 as the first global fatwa is issued against a writer, and writers and students in Tiananmen Square square off against China.]

Next Installment: PEN Journey 2: The Fatwa