Posts Tagged ‘Salman Rushdie’

PEN JOURNEY: Introduction—Raising the Curtain: The Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and was asked by PEN International to write down memories. I have done so in 46 PEN Journeys and have been asked to write an introduction to these. Below is the introduction coming last, drawn in part from an earlier blog post of the same title, but not in this PEN Journey sequence.

“In a world where independent voices are increasingly stifled, PEN is not a luxury. It is a necessity.”—Novelist & poet Margaret Atwood, former President of PEN Canada

“…freedom of speech is no mere abstraction. Writers and journalists, who insist upon this freedom, and see in it the world’s best weapon against tyranny and corruption, know also that it is a freedom which must constantly be defended, or it will be lost.”—Novelist Salman Rushdie, PEN member

PEN International was started modestly 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catharine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others, conceived if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, they reasoned, at least among writers of Europe.

PEN Founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and first PEN President John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN [Poets, Essayists & Novelists—later expanding to Poets, Playwrights, Essayists, Editors and Novelists and now including a wide array of Nonfiction writers and Journalists] spread quickly. Clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, and the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. A decade later when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, he donated the prize money to International PEN. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace. Galsworthy spoke about the possibilities of a “League of Nations for Men and Women of Letters.”

Members of PEN began to gather at least once a year in 1923 with 11 Centers attending the first meeting. During the 1920’s writers regardless of nationality, culture, language or political opinion came together. As the political temperature rose in Europe, PEN insisted it was an apolitical organization though its role in the politics of nations was soon to be tested and ultimately landed not on a partisan or ideological platform but on a platform of ideals and principles.

At a tumultuous gathering at PEN’s 4th Congress in Berlin in 1926, tensions rose among the assembled writers, and the debate flared over the political versus non-political nature of PEN. Young German writers, including Bertolt Brecht, told Galsworthy that the German PEN Club didn’t represent the true face of German literature and argued that PEN could not ignore politics. Ernst Toller, a Jewish-German playwright, insisted PEN must take a stand.

After the Congress Galsworthy returned to London and holed up in the drawing room of PEN’s founder Catharine Scott where he worked on a formal statement to “serve as a touchstone of PEN action.” This statement included what became the first three articles of the PEN Charter. At the 1927 PEN Congress in Brussels, the document was approved and remains part of PEN’s Charter today, including the idea that “Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.” The third article of the Charter notes that PEN members “should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people and dispel all hatreds and champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

As the voices of National Socialism rose in Germany, PEN’s determination to remain apolitical was challenged though the determination to defend freedom of expression united most members. At the 1932 Congress in Budapest the Assembly of Delegates sent an appeal to all governments concerning religious and political prisoners, and Galsworthy issued a five-point statement, a document that would evolve into the fourth article of PEN’s Charter.

When Galsworthy died in January 1933, H.G. Wells took over as International PEN President. It was a time in which the Nazi Party in Germany was burning in bonfires thousands of books they deemed “impure” and hostile to their ideology. At PEN’s 1933 Congress in Dubrovnik, H.G. Wells and the PEN Assembly launched a campaign against the burning of books by the Nazis and voted to reaffirm the Galsworthy resolution. German PEN, which had failed to protest the book burnings, attended the Congress and tried to keep Ernst Toller, a Jew, from speaking. Some members supported German PEN, but the overwhelming majority reaffirmed the principles they had just voted on the previous day. The German delegation walked out of the Congress and out of PEN and didn’t return until after World War II. Their membership was rescinded. “If German PEN has been reconstructed in accordance with nationalistic ideas, it must be expelled,” the PEN statement read. During World War II PEN continued to defend the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. (Today German PEN is one of PEN’s active centers, especially on issues of freedom of expression and assistance to exiled writers.)

PEN was one of the first nongovernmental organizations and the first human rights organization in the 20th century. PEN’s Charter, which developed over two decades, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II. In 1949 PEN was granted consultative status at the United Nations as “representative of the writers of the world,” and is today the only literary organization with formal consultative status with UNESCO.

In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in more than 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries, defend linguistic rights and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia in the late 1980’s and in other countries of the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar where a former prisoner of conscience was instrumental in forming a center there and was its first President. A PEN center is a refuge for writers in many countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

For more than 35 years I have been engaged with PEN, as a member, as the President of one of PEN’s largest centers, PEN Center USA West during the year of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie and Tiananmen Square, as Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), as International Secretary (2004-2007), and continuing as an International Vice President since 1996. I’ve also served on the Board and as Vice President of PEN America (2008-2015). I lived for six years in London, where PEN International is headquartered.

In the run-up to PEN’s Centenary, I was asked if I would write an account of PEN’s history as I’d seen it. I began by posting a blog twice a month, taking on small slices of the history in each narrative. This serial blog of PEN Journeys recounts PEN’s history as I’ve witnessed it as well as history of the period and personal history during those years. The narratives are framed by the times, featuring writers, including the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, the protests in Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall—PEN members or future PEN members were central in all these events—the collapse of the Soviet Union and the formation of PEN Centers there; the opening up of Eastern Europe with its PEN centers; the release of PEN “main case” Václav Havel and his ascendency to the Presidency of Czechoslovakia; the mobilization of Turkish PEN members in opposition to recurring authoritarian governments; PEN’s mission to Cuba; PEN’s protests over killings and impunity in Mexico; protests and gatherings in Hong Kong on behalf of imprisoned Chinese writers; the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Peace to PEN member and Independent Chinese PEN Center founder and President Liu Xiaobo.

PEN and its members have played a pivotal role in defending freedom of expression around the world, in challenging systems that trap citizens, and in at least two instances, in taking on the presidencies of the new democracies that emerged. The PEN Charter, which sets out the principles and ideals, has united the global organization and guided its members who have often been at the forefront or in the wings of important historical moments—celebrated and outspoken writers like Václav Havel, Nadine Gordimer, Margaret Atwood, Orhan Pamuk, Yaşar Kemal, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Koigi wa Wamwere, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Arthur Miller, Anna Politkovskaya, Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Carlos Fuentes, Liu Xiaobo. The list is long, and I have had the privilege of interacting with many of them in PEN and also with hundreds of perhaps lesser known, but courageous writers who have stood watch and engaged.

The view of PEN Journey is global though the work is often local. As well as chronicling global events and personal history, PEN Journey recounts the shaping and re-imagining of this sprawling nongovernmental organization, one of the largest in terms of geographic reach. PEN has had to evolve and re-shape itself to serve its 155 autonomous centers. With at least 40,000 members around the globe in more than 100 countries, there are many stories others might tell, but this narrative is a close-up view of a period of time and of the writers who continue to work together in the belief that the world for all its differences and complexities can aspire to and perhaps even achieve “the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”* [*PEN Charter]

Because I tended not to throw away documents over the decades, I have an extensive paper as well as digital archive which I used to refresh memories and document facts. As I dug through files, I came across a speech I’d given which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman speaking at PEN International Conference on Cultural Diversity in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005

The talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is ongoing. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King is quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

From Diyarbakir Conference:

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through PEN’s 141 centers in 99 countries. [Now 155 centers in over 100 countries.] They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see for himself this ancient city, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together.

–Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International, March 2005

PEN Journey 30: Barcelona: A Surprise

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I was having lunch with my husband at a Georgetown restaurant in Washington, DC on a Saturday in May, 2004. I was due to fly out the next day for Barcelona to attend International PEN Writers in Prison Committee’s 5th biennial conference, part of a larger Cultural Forum Barcelona 2004. My husband and I were talking about our sons—the oldest was getting a PhD in mathematics and was also training for the 2004 Olympics as a wrestler, hoping to make the British team. (He had dual citizenship.) The younger, recently graduated with an advanced degree in International Relations, had just deployed to Iraq as a Marine 2nd Lieutenant and was heading into a region where the war was over but the insurgency had begun. It was an intense time for our family, yet as parents there was not much we could do except to be there, cheering for our oldest at his competitions and writing letters and sending packages and prayers for our youngest. It was a time when as parents we realized our children had grown beyond us and were taking the world on their own terms.

I was planning to be away for the week in Barcelona where PEN members from around the world were gathering for the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) and Exile Network meetings. Carles Torner, PEN International board member, chair of PEN’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and former President of Catalan PEN, had helped arrange International PEN’s participation and funding as part of the Universal Forum of Cultures—Barcelona 2004. This would be the largest WiPC conference to date with delegates from every continent and multiple speakers and side events.

Carles, a poet, fluent in PEN’s three official languages English, French and Spanish, was one of the highly respected, organized and talented PEN members. He’d also been involved in the years’ long reformation of PEN International. As members looked to who could be a strong replacement for the current International Secretary when Terry Carlbom’s term ended in a few months, there was widespread enthusiasm for Carles to stand for the office. I was among the enthusiasts.

My phone rang at that Saturday lunch. International PEN Board member Eric Lax, already in Barcelona for meetings, said he had news and a question; he told me he was calling on behalf of others as well. The news: the Catalan government had also recognized Carles’ talents and had offered him a position as Director of Literature and Humanities Division at Institut Ramon Llull to promote Catalan literature abroad. A father of three, Carles had accepted this paid position which meant he couldn’t stand for PEN International Secretary, an unpaid position. He wouldn’t have the time for both, and there would be conflicts of interest.

Eric asked if I would allow myself to be nominated. A number of members and centers, including the two American centers, were asking, he said. PEN’s Congress where the election would take place was only a few months away in September and nominations were due soon. I was flattered but said no for a number of reasons. Eric asked that I not answer yet, just come to Barcelona, talk with people and let them talk with me.

The International Secretary who worked with the Board and President to run International PEN was not a position I aspired to, but I agreed to come to Barcelona with an open mind. I’d worked with PEN in various roles, including as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee, for over 20 years. I’d been both inside and outside the reform process that was going on. I understood, at least in part, what PEN was aiming towards and what it would take for this sprawling organization to operate competitively among nongovernmental organizations in the 21st century. I’d sat on boards of several global nonprofit organizations, including Human Rights Watch, Save the Children and the International Crisis Group.

PEN Writers in Prison Committee Center to Center newsletter Spring, 2004

In Barcelona delegates from a number of PEN centers urged me to stand for the office. I asked whether they thought this was the time for an American to take on this leadership role given the controversy over US engagements. “We don’t think of you as American,” some said, perhaps because I’d also lived in Europe for six years during my work with PEN.

I kept my own personal life quiet as I always did, but I did share with Carles, who was urging me to stand, that I had a son in the Marines in Iraq and was committed to him. I didn’t want to get involved in political controversies over the war. “Your focus has always been on freedom of expression,” Carles reminded me. PEN was not an anti-war organization; its focus was on protecting freedom of expression for writers to agree or disagree on issues, not to take political positions unless relating to abuses of human rights.

Mike Roberts, PEN American Center’s Executive Director, was among those encouraging me to stand for the office. He said American PEN would support me however they could with help and advice. We both understood that the organizational models of many American nonprofit organizations could benefit PEN, including the need to have a paid executive director. There was much to be said for the culture of the volunteer which PEN operated in, but given how complex and widespread PEN’s work had grown, it was going to be more and more difficult to compete for funding if there was not a paid professional executive director in the international office in addition to the talented administrative staff and Board of PEN. Certain funders were already telling us as much. Case in point was that Carles, an experienced literary organizer with a family to support, simply could not afford to take on such a demanding position gratis. Eugene Schoulgin, chair of the Writers in Prison Committee, also encouraged me. I left Barcelona thinking deeply about standing for this position which would require significant time and travel.

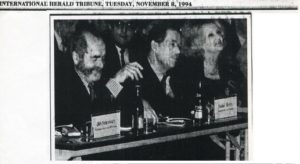

PEN Program at Cultural Forum Barcelona 2004. L to R: Carles Torner, International PEN Board Member and director for PEN conference, Salman Rushdie, President American PEN, Josep Bargalló, First Minister of Catalonia, Dolors Olier, President Catalan PEN

That question absorbs many of my personal memories about the Barcelona conference. I remember the impressive venue and the conversations with friends and colleagues and the many presentations, including by Anna Politkovskaya and an opening talk by Salman Rushdie, the new President of American PEN who called for the US government to open a wider dialogue with the world.

Fortunately, I have papers from the 2004 Writers in Prison Committee meetings. We met over five days and also joined public discussions on literature and memory and the responsibility of writers during times of war. The WiPC continued its focus on issues of impunity and the effect of anti-terror legislation on free expression as documented in PEN International’s two reports issued the previous year.

Joan Smith of English PEN reported that anti-terror legislation was having an impact with democratic countries reacting out of fear to the events of September 11 and either tightening existing legislation or implementing new legislation. Countries such as Cuba were taking advantage for as attention deflected from them, they were cracking down on more dissidents. Countries such as Uzbekistan and other Central Asian countries were using the war against terrorism to win support from the US and western Europe.

Müge Sökmen of Turkish PEN spoke of the danger of silencing dissident voices, a move that would lead to an increase in state terrorism. Since the 9/11 attacks in the US there had been a 20% increase in the number of imprisoned writers. The lifting of Article 8 of the Turkish Anti-Terror Law was welcomed but was in the context of Turkey’s bid for acceptance into the European Union.

Ragip Zarakolu, a Turkish publisher, and Martxelo Otamendi, director of a Basque newspaper, reported to the meeting on their experiences of repression and imprisonment under the anti-terror laws.

Report on 5th International PEN Writers in Prison Committee Conference as part of Barcelona Forum 2004, including preliminary meetings in London, New York, Istanbul and Ottawa.

Nigerian writer and journalist Kunle Ajibade, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment in 1995 for “conspiring to overthrow the government,” had been freed in 1998 in part because of PEN’s work. But he told the group, “Many of us have been asking, is this what we went to jail for? What has all our struggle come to? A mere clearing of the path for another set of murderers and looters? Right now, a cloud of despair hangs over us.”

Ali Lmrabet, Moroccan journalist, who had been sentenced to three years for insulting the King, also spoke. However, Cheikh Kone, a journalist from the Ivory Coast who’d fled to Australia, had been denied a visa to Spain and so an empty chair was placed at the speaker’s table. Kone had been detained since 2001 in a refugee camp in Australia and was finally released in July 2003 after PEN’s campaign, but the Australian government had invoiced him for $89,000 for the cost of his detention.

Aaron Berhane, an Eritrean journalist who fled to Canada in 2002 reported his situation and the help International PEN’s WiPC and Canadian PEN had given through the Writers in Exile Network. The Network, started in 1994, was currently chaired by PEN Canada and included PEN centers in Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, England, USA West, and Germany and had helped exiles from Cuba, Sierra Leone and other countries.

A panel with representatives from OSCE, UNESCO, the UN Human Rights Commission, the International Publishers Association (IPA), and the International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) gathered with PEN to explore cooperation and joint work around issues of freedom of the media, including campaigns on individual cases and pressure on countries to change their laws to conform to democratic standards.

Report on PEN Writers in Prison Committee statement to UN Commission of Human Rights, April, 2004

Ambeyi Ligabo, Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression in the office of the UN Commissioner on Human Rights said he believed the two new threats to freedom and liberty were terrorism and anti-terrorism legislation. He was concerned that countries such as Denmark which professed to be a beacon of democracy were actually denying liberties to their citizens. He was concerned that legislation introduced in some African countries had undermined the progress human rights campaigners had achieved, and he urged collaborative efforts in fighting new threats to free expression.

The WiPC Steering Committee, which consisted of representatives from ten PEN centers, presented its report with suggestions for WiPC headquarters and for the PEN centers on how to expand PEN’s work, its outreach, its funding and its cooperation. A three-year plan was adopted.

The final work of the WIPC conference was an agreement on a campaign calendar for 2004-2005 with an over-arching theme on the issue of Freedom of Expression and Anti-Terrorism.

In accepting PEN’s WiPC statement on freedom of expression from the conference whose theme was “The Value of the Word,” Catalonia’s Minister of Culture declared: “The word is an inspiration for the imagination, a means for peace and a vehicle for freedom. Literature and the word must always be above conflict. PEN has been in the forefront in the fight to secure the value of the word. The value of the word is a guarantee for a better world and more necessary than ever.”

It was agreed the next WiPC Conference would be held in Istanbul in 2006, hosted by Turkish PEN.

La Sagrada Familia—Gaudi Cathedral—in Barcelona, Spain

Before I left Barcelona, I went to visit the Gaudi Cathedral (La Sagrada Familia) which I’d first seen at PEN’s 1992 Barcelona Congress where I’d been so impressed by its majesty and complexity, I wanted to return. Architect Antoni Gaudi had originally planned a cathedral with 18 Gothic spires, but he got hit and killed by a trolley before his elaborate design was realized. Over 100 years later, the cathedral was still unfinished. Gaudi had applied for a construction permit in 1885 but no one ever answered. (It took the city 137 years before a building permit was finally issued in 2019, along with a $5.2 million fee.)

Gaudi defined architecture as the “ordering of light” so that the sun shined differently on the cathedral stones at each moment of the day, producing the myriad effects of light. In the intervening years others had worked to complete Gaudi’s design, but the cathedral remained unfinished. It was nonetheless a magnificent architectural achievement, a harmony or even disharmony of hundreds/thousands of artisans over the century who created this living work of art. I stood in an open space and stared up at the sky.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 31: Tromsø, Norway: Northern Lights

PEN Journey 12: Tolerance on the Horizon?

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

It was a time of hope, the year when Nelson Mandela and Frederik de Klerk joined in free elections in South Africa, when Yasser Arafat, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres shook hands and began to live side by side, when the Irish Republican Army and the Ulster Defense Association laid down their arms after twenty-five years of terrorist conflict. The idea of tolerance quivered in the imagination in 1994 even if the realization of tolerant societies still seemed an imaginative leap.

As theme of the 61st PEN Congress, tolerance also challenged the ethnic, national and religious intolerance that gripped dozens of countries in the last decade of the twentieth century. In retrospect the time was perhaps not so different from times since, but we felt we were standing on an historic threshold. The PEN Congress theme of tolerance expressed this hope and optimism.

Liechtenstein Palace, garden view

Writers from over 75 PEN centers* around the world came together in Prague that fall for literary and working sessions. The Congress was a grand affair with public gatherings in stately ballrooms, including the Liechtenstein Palace, home of the Prague Academy of Music. Writers who had been imprisoned under the old Soviet regime, including Václav Havel, now ran the country.

Guests of honor included novelist and poet Taslima Nasrin, whom PEN had recently helped extract from the threat of death in Bangladesh (see PEN Journey 11). For protection she was driven around in a state car, and because Sara Whyatt, coordinator of the PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), and I agreed to look after her, we at times found ourselves whisked from meeting to meeting with a police escort, not the usual transport at a PEN Congress.

Though PEN had no mechanisms to change societies, to the extent society changed individual by individual, PEN worked for the writer, turning a spotlight on cases of abuse and challenging the laws which legitimized intolerance.

The voice of the individual writer has always been the most compelling testimony. My report to the Assembly of Delegates that year as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee focused on those voices:

“Yes, I can hear birds singing. But they are not my friends. They are too far from me. My best friends are spiders and mantis. They are only living things to watch amusedly in my solitary cell. I live and play with them all day long. This excerpt is from a prisoner ten years into a twenty-year sentence written to his PEN minder.

“The image of the spider recurs in the writings of prisoners. One former prisoner I met shortly after taking over as Chair of this committee had come to London to receive treatment for the torture he’d endured. He told of being handcuffed to a generator outside during monsoon season, of not being allowed to wash, using a bucket as a toilet, his arms and hands wrapped around the generator for weeks. Then he talked about being inside in solitary confinement. ‘I had a chance to observe nature: rats, cockroaches, spiders,’ he recalled. ‘Ah, spiders, they are brilliant!’

“Cuban writer Yndamiro Restano, who was arrested in 1991 and sentenced to ten years in prison for preparing and distributing counter-revolutionary propaganda, has written a poem entitled Prison:

Mother,

Do you know where your poet is?

Well, they have dragged me into a dark,

Narrow, lonely cell,

And do you know why,

Mother?

For not allowing fear to carry me away.

But I am not completely alone,

Mother.

I have got to know a good friend here.

A small spider visits me every day

And spins in the door of my cell.

When the guard comes,

I let it know so it hides away.

And doesn’t get killed.

I want it to live,

Mother,

Because I know that it has inside it

Something that I also possess.

However,

It seems that the guard does not know this.

Mother,

Do you know where your poet is?

Well, they have dragged me to a cold,

Narrow, lonely cell.

And do you know why,

Mother?

Because the poet is the only person

Who never forgets

The meaning of freedom.

“The quality the spider has inside so like the writer is the ability to survive, to weave and to work wherever it is. The more difficult the circumstances, the more ingenious the web it weaves. Scientists are in fact currently studying the unique structure of the spider’s silk which gives it the tensile strength of a steel fiber, yet allows it to stretch and rebound from at least ten times its original length, something no metal or synthetic fiber can do.

“The writer’s silk, his tensile yet flexible fiber, is his imagination. It is the imagination and the life of the mind that allows the writers for whom the Writers in Prison Committee works to survive what are sometimes quite desperate physical conditions. One quality that gives the imagination its greatest flexibility and strength is tolerance, the theme of this Congress. It also is that quality and the ability to imagine and empathize with another’s life that prompts those not in prison or under attack to work on behalf of their fellow writers.

“The work of PEN members and Centers in 1994 has been inspiring even if the situation for the writers has been very difficult in many areas of the world. This past year has witnessed some remarkable moves towards tolerance: in South Africa with the first free elections, in Israel and the West Bank with the Israeli-Palestinian peace accord. The WiPC case load has declined with release of political prisoners in these areas, but writers remain in the line of fire and are still targets of those who are trying to disrupt the peace process.

“The past year over 120 writers have been released from prison. Unfortunately many times that number have been arrested, threatened and killed.

“Religion, ethnic and nationalistic tolerance has led to attacks and detention of writers in every area of the world. Religious intolerance of one kind or another continues to undermine intellectual freedom in Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Mauritius, Sudan, Egypt, Vietnam and Algeria.

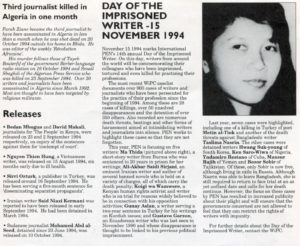

“Often religion is used to justify political interests. No place has the confrontation between “religious” and state power been more devastating than in Algeria, where over 25 writers and journalists have been killed and dozens detained in the past two years.

“Ethnic, national and religious intolerance often merge as in the former Yugoslavia and other areas of the Balkans.

“The most brutal outbreak of ethnic intolerance globally this year has been in Rwanda, where over 37 writers and journalists have been killed, most targeted for their ethnic, and thus political background.

“Ethnic conflict, which is also political conflict, currently stirs in Nigeria where Ken Saro Wiwa, advocate for the Ogoni people, is in jail and reportedly tortured and in Kenya where Koigi wa Wamwere exposed “ethnic cleansing” in the Rift Valley and has been detained on charges which carry the death penalty.

“The most difficult country with the largest number of Writers in Prison Committee cases continues to be Turkey where those discussing and debating the Kurdish situation in the Southeast are charged with “disseminating separatist propaganda” under Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law and are imprisoned. Killings and torture are reported by both sides of this conflict. PEN records over 250 cases in Turkey.

“The other country which continues to lead our list with the most main cases is China where over 45 writers, a third of these in Tibet, are imprisoned. Though China has released some prominent dissidents this year, the Chinese authorities have also arrested at least twice as many writers as they have released…”

From PEN’s Centre to Centre newsletter October/November, 1994.

The Chair’s report for 1994 notes progress but also shows how little has changed for writers in the past 25 years in many areas of the world such as Turkey and China though there has been progress in Algeria, Rwanda, the Balkans, Nigeria and Kenya. The Day of the Imprisoned Writer campaign in November, 1994, noted in the newsletter above, focused on five writers. Of these Ma Thida was released and eventually started a Myanmar/Burma PEN Center and now serves on the PEN International Board; Koigi wa Wamwere was released and is a celebrated Kenyan writer. Gunay Aslan and Gustavo Garzon, also released, continue to create. Ali-Akbar Sa’idi Sirjani died in Iranian prison under mysterious circumstances in November 25, 1994.

With attention and advocacy, circumstances improve for individual writers, but many writers who are released have to go into exile. At the Prague Congress PEN began to expand its thinking and resources to develop services for exiled writers. (Future blog post.)

A highlight of the 61st Congress was the address by Czech President Václav Havel, fellow writer and playwright whose first play “Garden Party” lampooned the communist system in 1963. In 1969 he was barred from his job as a writer/editor after the suppression of the Prague Spring reforms in 1968, and he was forced to work as a manual laborer. In 1977 he became the spokesman for the Charter 77 dissident group that criticized the communist officials and was given a suspended sentence of 14 months. After publishing in 1978 “Power of the Powerless” which was an analysis of how a totalitarian regime kept power by corrupting and manipulating citizens, he was sentenced to four and a half years in prison for “subversion” against the state. During this time PEN worked actively on his case, pressuring diplomats around the world. Havel was released after three and a half years but then imprisoned again after meeting dissidents and the French President in Prague in 1989. Havel was sentenced to nine months, but widespread protests from home and abroad, many generated by PEN, brought his release in May. In November, 1989 the communist regime fell. In December 1989 Václav Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia, which eventually split. At the time of the PEN Congress he was in his first year as President of the newly independent Czech Republic.

Left to right: Jiří Stránský, President Czech PEN, and Czech President Václav Havel

Abridged speech of Václav Havel to the Opening of the 61st PEN Congress in Prague November 7, 1994:

“Several times in my life I have had the honour of being invited to a world congress of the International PEN Club. But the regime always made it impossible for me to attend. I had to live to the age of fifty-eight, go through a revolution in my country, become the nation’s president, and see the World Congress held in Prague, to be able to participate in this important event for the first time in my life. I am sure you will understand therefore, that this is a very moving moment for me.

“Yes, we live in a remarkable time. It is not just that we now learn, almost instantaneously, about all the deeply shocking atrocities that take place in the world; it is also a time when every local conflict has the potential to divide the international community and become the catalyst for a far wider conflict, one that in many cases is even global. Who among us, for instance, can tell where the present war in Bosnia and Herzegovina may lead, to what tragic confrontation of three spheres of civilization, if the democratic world remains as indifferent to that conflict as it has so far?

“I think that in these matters, writers and intellectuals can and must play a role that only they can fill. They are people whose profession, indeed, whose very vocation is to perceive far more profoundly than others the general context of things, to feel a general sense of responsibility for the world, and to articulate publicly this inner experience.

“To achieve this, they have essentially two instruments available to them.

“The first is the very substance of their work—that is, literature, or simply writing. Deep analysis of the tangled roots of intolerance in our individual and collective unconsciousness and consciousness, a merciless examination of all the frustrations of loneliness, personal inadequacies and the loss of metaphysical certainties that is one of the sources of human aggression—quite simply, a sharp light thrown on the misery of the contemporary human soul—this is, I think, the most important thing writers can do. In any case, there is nothing new in this: they have always done that, and there is no reason why they should not go on doing so…

“But there is another instrument, an instrument that intellectuals sometimes avail themselves of here and there, though not nearly often enough in my opinion. This other instrument is the public activity of intellectuals as citizens, when they engage in politics in the broadest sense of the word. Let us admit that most of us writers feel an essential aversion to politics. We see entering politics as a betrayal of our independence, and we reject it on the grounds that the job of the writer is simply to write. By taking such a position, however, we accept the perverted principle of specialization, according to which some are paid to write about the horrors of the world and human responsibility, and others to deal with those horrors and bear the human responsibility for them. It is the principle of a rather doubtful division of labour: some are here to understand the world and morality, without having to intervene in that world and turn morality into action; others are here to intervene in the world and behave morally without being bound in any way to understand any of it…

“In short, I am convinced that the world of today with so many threats to its civilization and so little capacity to deal with them, is crying out for people who have understood something of that world and know what to do about it to play far more vigorous role in politics. I felt this when I was an independent writer, and my time in politics has only confirmed the rightness of that feeling, because it has showed me how little there is in world politics of the mind-set that makes it possible to look further than the borders of one’s own electoral district and its monetary moods, or beyond the next election.

“I am not suggesting, dear colleagues, that you all become presidents in your own countries, or that each of you go out and start a political party. It would, however, be wonderful if you were to do something else, something less conspicuous, but perhaps more important: that is, if you would gradually begin to create something like a world-wide lobby, a special brotherhood or, if I may use the word, a somewhat conspiratorial mafia whose aim is not just to write marvelous books or occasional manifests, but to have an impact on politics and its human perceptions in a spirit of solidarity, and in a coordinated, deliberate way…”

“Let me conclude with one final plea: do not fail to raise your common voice in defence of our colleague and friend Salman Rushdie, who is still the target of a lethal arrow, and in defence of Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, who is unable to join us here because his government prevented him from coming. I also beg you to express our common solidarity with all Bosnian intellectuals who have been waging a courageous and unequal struggle on the cultural front with the criminal fanaticism of the ethnic cleansers, those living examples of the lengths to which human intolerance can eventually go.”

Next Installment: PEN Journey 13: PEN and the U.N in a Changing World

*Delegates representing 73 PEN Centers attended the 61st Congress, along with observers from three proposed new centers—Malawi, Guadalajara and Iranian Exiles Abroad. All three were elected as new PEN centers at the Congress, along with new centers in Ghana and Kyrgyzstan and a revived Egyptian PEN center.

PEN Journey 9: The Fraught Roads of Literature

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

Twelve-foot puppets danced outside the dining room’s second floor windows at our hotel, billed as the “oldest hotel in the world,” set on the central plaza of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, the venue for PEN International’s 60th Congress.

Sara Whyatt, coordinator of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, and I hurried to finish breakfast and our agenda before we joined the crowds outside at the historic Festival of St. James. That evening International PEN’s 60th Congress would convene. Hosted by Galician PEN, the Congress had as its theme Roads of Literature, which seemed appropriate as pilgrims from around the world also gathered on the Obradoiro Plaza in front of the ancient Cathedral, the destination for their Camino.

Parador Hotel, Santiago de Compostela St. James Festival, Obradoiro Plaza, Santiago de Compostela

At this Congress the presidency of PEN was changing hands as was the chairmanship of the Writers in Prison Committee, which I was taking over from Thomas von Vegesack. Ronald Harwood, the British playwright, was assuming the PEN presidency from Hungarian novelist and essayist György Konrád, who had been a philosophical president, often running the Assembly meetings like a stream of consciousness event where the agenda was a guide but not necessarily a governing map. Ronnie ran the final meeting like a director and dramatist, determined to get the gathering from here to there with a path and deadline. Both smart, experienced writers, committed to PEN’s principles, they had very different styles. Known only to a few of the delegates a surprise visitor was also arriving mid-Congress.

The 60th Congress in September 1993 was a watershed of sorts. It was the first since the controversial Dubrovnik gathering six months before which had split PEN’s membership (see PEN Journey 8) because of the war in the Balkans.

Konrád’s opening speech to the Assembly explained that PEN’s leadership had gone ahead with the congress over the many objections from PEN centers because the venue had been approved earlier by the Assembly and the host center had been unwilling to postpone. He acknowledged the widespread criticism and also the concern that some individuals who fomented the Balkan wars and participated in alleged war crimes were writers who had been members of PEN. He said, “That these men of war also include men of letters, indeed that these latter are well represented, painfully confronts our professional community with the notion of our responsibility for the power of the Word. Nationalist rhetoric led to mass graves here, and there. Mutual killings would not have been on such a scale in the absence of words that called on others to fight or that justified the war.”

György Konrád, PEN International President 1990-1993, Credit: Gezett/ullstein bild, via Getty Images

Konrád’s address at the opening session went a way in bringing the delegates together. “What we can do is to try and ensure the survival of the spirit of dialogue between the writers of the communities that now confront each other….International PEN stands for universalism and individualism, an insistence on a conversation between literatures that rises above differences of race, nation, creed or class, for that lack of prejudice which allows writers to read writers without identifying them with a community…

“Ours is an optimistic hypothesis: we believe that we can understand each other and that we can come to an understanding in many respects. The existence of communication between nations, and the operation of International PEN confirm this hypothesis…PEN defends the freedom of writers all over the world, that is its essence.”

Ronald Harwood added in his acceptance for the presidency: “The world seems to be fragmenting; PEN must never fragment. We have to do what we can do for our fellow-writers and for literature as a united body; otherwise we perish. And our differences are our strength: our different languages, cultures and literatures are our strength. Nothing gives me more pride than to be part of this organization when I come to a Congress and see the diversity of human beings here and know that we all have at least one thing in common. We write…We are not the United Nations…We cannot solve the world’s problems…Each time we go beyond our remit, which is literature and language and the freedom of expression of writers, we diminish our integrity and damage our credibility…We don’t’ represent governments; we represent ourselves and our Centres…We are here to serve writers and writing and literature, and that is enough…And let us remember and take pleasure in this: that when the words International PEN are uttered they become synonymous with the freedom from fear.”

Ronald Harwood, PEN International President 1993-1997. Credit BAFTA

PEN’s work to defend writers and protect space free from fear fell in large part to the Writers in Prison Committee, the largest of PEN’s standing committees with over half the PEN centers operating their own WiP Committees. Members elected the writers who were in prison for their writing as honorary members of their centers, corresponded with them and their families, advocated on their behalf with their own governments and with the governments where the writers lived. PEN’s London office provided the research, selected the cases, planned campaigns and worked with international bodies. The means and methods have modified over the years as the internet and social media have developed, but the focus has remained on the individual writer whose case is pursued until it is resolved. With consultative status at the United Nations, International PEN and its Writers in Prison Committee work through the Human Rights Commission and UNESCO and with other international institutions lobbying on behalf of writers.

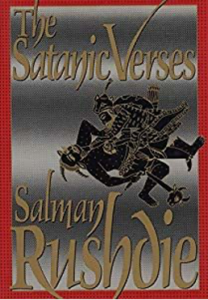

At the time of the 60th Congress focus of WiPC’s work included China, Turkey, Algeria, Burma, Syria and Nigeria. In Turkey that summer an arson attack at an arts festival in Sivas had killed at least 37 people, seven writers and poets. One of the writers at the festival Aziz Nesin was translating Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses into Turkish and had started to serialize the book in a newspaper. Nesin’s presence at the festival was said to inflame the local crowds. Though Nesin survived, it was reported he was beaten by the firefighters who saved him, and a subsequent investigation held the Turkish state responsible. China continued to have more WiPC cases than any country except Turkey. The threat of death for writers had intensified in Algeria where Islamic extremists had assassinated six writers, including the novelist and journalist Tahar Djaout. In Nigeria the brief imprisonment and possible sedition charges against writer Ken Saro Wiwa, President of the Nigerian Association of Authors, founding member of Nigerian PEN and leader of the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People was highlighted after his passport was confiscated. A few years later his situation would inspire a global mobilization by PEN and human rights groups after Saro Wiwa was condemned to death by Nigeria’s de facto President Sani Abacha.

The focus of the 60th Congress remained on the Balkans and on growing religious extremism. PEN’s surprise guest appeared at the Assembly in the middle of the Peace Committee report on the Balkans. That morning delegates had entered through a metal detector and security check, the first and only time in my years at PEN. The day before, the guest was to have slipped into the hotel secretly because of security concerns, but the plaza outside was filled with people who had come to see the arrival not of Salman Rushdie but of singer Julio Iglesias who arrived at the same time. Rushdie was quickly whisked inside. That evening a small group gathered for dinner with Rushdie in a private dining room at the hotel. I remember sitting beside Salman and sharing a dessert with him but have no notes from the dinner and remember only a discussion of PEN’s further campaign on his behalf. At the time the fatwa weighed heavily. Translators and publishers of Rushdie had been killed and attacked.

The next morning Rushdie arrived in the hall during the Peace Committee’s report which took a break for Rushdie’s address. The Assembly passed a resolution again condemning the fatwa and urging Iran to rescind it and urging all PEN Centers to continue lobbying their governments on Rushdie’s behalf and to put the case on the agenda of the International Court of Justice and other multilateral fora.

International PEN 60th Congress Assembly of Delegates in Santiago de Compostella 1993. Left to right: György Konrád, Salman Rushdie, Ronald Harwood

To the Assembly Rushdie noted: “…in the Muslim world, in the Arab world when journalists and academics and other visitors ask writers, intellectuals, and other dissident figures in those countries what they think, they repeatedly say: ‘The reason you must defend Rushdie is that by doing so you defend us also.’ For example, Iranian dissident intellectuals, 167 of whom recently signed a very passionate declaration in support of me and of the principles involved in this case, say that the real target of the Khomeini Fatwa and of Iranian state terrorism is not Rushdie, it is them.’ After all I have protection; they don’t. And what the terror campaign means is ‘If we can do this to Rushdie, think how much we can do to you.’”

He said, “There is something I wanted to say about the issue of fear. I do think that a lot of people who mean well and wish to combat this kind of attack are silenced by fear, and think that by remaining silent, somehow things will get better…But the one thing that I’ve learned is that silence is always the biggest mistake, always no matter how great the temptation to silence might be, for a very simple reason. If you are silent, you allow your enemy to speak, and therefore you allow him to set the terms of the debate…I think one of the reasons I’m here is that all of you, and thousands of people around the world have not remained silent.”

Rushdie thanked PEN for its work on his behalf. When asked how this situation affected his writing, he said he’d actually become more optimistic. “I was determined to construct a happy ending and discovered it is very difficult. Happy endings in literature as in life are very difficult to arrange…[but] the answer is that it’s made my writing much more cheerful.”

Rushdie stayed after his address and participated in the discussion on the Balkans. Miloš Mikeln, chair of the Peace Committee, reported that besides help provided to writer refugees and those staying in Sarajevo, the Peace Committee was closely following and analyzing the situation in the war regions, focusing on writers’ involvement in instigating chauvinistic hatred and war propaganda. The most drastic case was that of the Serbian poet from Bosnia, Mr. Radovan Karadzic, who was now the President of the self-proclaimed Serbian Republic of Bosnia. The Peace Committee report noted that he’d used his literary talent and his reputation as a writer to foster ethnic and religious hatred and to promote genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina. “As writers who deeply believe in freedom of expression we cannot remain silent in the face of such an abuse of the freedom,” Mikeln said. “We find it incumbent upon us to condemn Radovan Karadzic for his violation of all the values that we and International PEN stand for.”

After lengthy debate on whether to name names in resolutions, this condemnation was accepted and taken as a statement of the Writers for Peace Committee. Personal condemnation is highly unusual for PEN, used most notably in the expulsion of Nazi writers in 1933. The debate further focused on the responsibility of PEN members, in particular Serbian PEN members and the Serbian center. It is also very unusual for the PEN Assembly to publicly call out a center. The resolution noted, “Writers in Serbia actively supported chauvinistic propaganda, misusing their influence as writers and thus instigating hatred, destruction and war. These actions including public statements by ___ and _____clearly run against the principles of International PEN. The 60th World Congress…condemns such a blatant abuse of our profession. We expect the Serbian PEN to take a stand against this breach of writers’ ethics as we would expect of any Center confronted by a similar situation.” In this instance the names were included in the original resolution but after debate were left out of the resolution passed by the Assembly.

The Bosnian delegate made a passionate plea protesting what was happening in Bosnia and the characterization of the situation as “civil war” by others. Rushdie said that the delegate from Bosnia was justified and should be heard. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the situation, there was no question that the crimes committed against Bosnia had been the greatest and Sarajevo the most tragic case, Rushdie said, and he hoped the delegate was wrong when he said people outside did not care and did not want to know. The destruction of Sarajevo would haunt Europe for generations, and he added that the people who had wanted to maintain a unified society had been sacrificed, and it was hard not to believe that it was because they were Muslims. Suppose the Serbs had been Muslims. The Bosnian culture was the culture of Europe.

The Assembly of Delegates approved the Peace Committee’s resolution with names removed and also endorsed a recommendation by Russian PEN that was to be annexed to the resolution. That statement declared that PEN “expresses its firm conviction that the duty of writers, and particularly of the writers of those ethnic groups and countries which are directly involved in the armed conflicts is not to espouse national interests but, in the cause of the unity of the world, promote negotiation and compromise so as to obtain the solution of all conflicts.”

PEN Congresses are full of speeches and resolutions, words offered in a world buffeted by much harder power, but PEN members have faith that words matter and can have power for good or ill, that there is a difference between words that aim for truth and words that are used for propaganda. At that time and in times before and since, words have inspired peace but also inflamed towards war. PEN remains a place where words and actions come together in campaigns to preserve the freedom of writers to use their words.

At the 60th PEN Congress in the grand ballroom of the oldest hotel in the world a new Bosnian Center whose members were Serb, Croat and Bosnian was unanimously welcomed as was an ex-Yugoslav Center for writers who no longer lived in the region.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 10: WiPC: Beware of Principles

PEN Journey 7: PEN in Times of War and Women on the Move

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Iraq invaded Kuwait August 2, 1990. When I picked up my 10-year old son from camp in the U.S. that summer and told him what had happened, his first response was: What about Talal and Alec? These were two of his good friends at the American School in London—one was son of the Kuwaiti Ambassador; the other was from Iraq. He quickly understood the consequences. Fortunately, both of his friends had been out of their countries at the time, though I don’t recall Alec returning to the American School that fall. When the bombs dropped on Baghdad in January, the American School went into lockdown. The older students were issued identity cards. The security force around the school multiplied. When Talal came over to play that winter, he was accompanied by two imposing body guards who stayed outside.

Though the fighting in Iraq concluded by the end of February, security in London continued. By the end of March, the war in the Balkans had begun. Both wars brought to a close the honeymoon many felt after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

For PEN, the outbreak of war in Iraq and in the Balkans led to the cancellation of the planned Delphi Congress and to the convening of conferences in Europe and a two-day gathering of PEN’s Assembly of Delegates and international committees in Paris in April 1991. Delegates from 39 PEN centers came together to conduct the business of PEN at the Société des Gens de Lettres de France which occupied the 18th-century neoclassical Hôtel de Massa on rue de Faubourg-Saint-Jacques in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. There were no literary sessions or social gatherings, or the usual simultaneous translation of proceedings. The business was conducted primarily in English with intermittent French, the two official languages of PEN. (Spanish was added a few years later as PEN’s third official language.)

The Gulf War, the ethnic conflict in the Balkans, the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square trials and the ongoing fatwa against Salman Rushdie predominated discussions in Paris and later in November at the 56th PEN Congress in Vienna. The Gulf War had resulted in increased numbers of writers imprisoned and killed in the Middle East and an increase in censorship. Resolutions condemning the detention and imprisonment of writers in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Israel and Turkey passed the Paris Assembly. Little information was available from Iraq. Another resolution in Paris sponsored by the two American centers expressed concern to the U.S. government and all U.N. member states over the restrictions placed on journalists during the war and urged a review of the ground rules for journalists in conflicts.

Turkey and China continued to hold the largest number of writers in prison, as has been the case for most of my 30-year involvement with PEN. At the time the Turkish government had announced an amnesty for approximately a third of the writers, and there was some hope they might release the additional 80, but new laws were also proposed that could be used against writers. In China where 87 cases were reported, the authorities had announced the end of investigations on the leaders of the June 1989 Democracy Movement. Most sentences were lighter than expected with credit given to human rights organizations like PEN who had kept up pressure.

However, this was not the case for Wang Juntao, a 32-year old academic and Deputy Editor of the Economics Weekly newspaper. In a letter to his lawyer published at the time in The South China Morning Post Wang Juntao explained why he had spoken as he had at the trial even though he knew his penalty would be more severe. “…Only by so doing can the dead rest in peace, since on the soil where they shed blood there are still some compatriots who take risks and speak out from a sense of justice in the most difficult circumstances…” His lawyers had been given just four days to prepare his defense. He was sentenced to 13 years in prison with four years subsequent deprivation of political rights for the crime of conspiracy to subvert the government and for carrying out counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement. His lawyers pressed him not to appeal so his wife had to do so and was given only three days. The appeal was rejected. [In 1994 Wang Juntao was one of the prisoners the U.S. demanded be released as a condition for trade talks. He was released from prison for medical reasons and now lives in exile in the United States where he has studied and received advanced degrees from Harvard University and a PhD from Columbia University. PEN was among the organizations which lobbied for this release.]

PEN International’s case sheet for Wang Juntao sent by fax and mail in 1990 to centers and members. In 1991 PEN International launched a Rapid Action Network to notify centers and to summarize the cases, actions and advocacy.

During this period PEN through its partnership with UNESCO convened writers in the Middle East and also writers in the Balkans to find common ground and to search out the pylons upon which bridges might be built and to monitor the situation for the writers in the regions. However, because of the Balkan War, it wasn’t possible to hold the meeting with the Yugoslav Centers in Bled as the Slovene Center had proposed. Instead PEN International President György Konrád hosted the gathering in Budapest and followed up with a meeting of South-Eastern European centers in Ohrid, hosted by Macedonian PEN though the Croatian Center wasn’t able to attend. The discussion included the desirability of recognizing the right of conscious objection in time of civil war and the possibility of solving the problem of minorities by allowing multiple citizenship.

Summary statement of the August, 1991 Conference on the Balkans with all centers from the former Yugoslavia attending except the Bosnian Center, which didn’t come into being until the following year.

In addition to convening dialogues among writers and lobbying on behalf of threatened writers during the Balkan conflicts, PEN also provided financial assistance. Boris Novak, the Slovene Chair of PEN’s Peace Committee and President of Slovene PEN took many precarious trips into war-torn Sarajevo during the almost four-year siege of the city. At one point he reported at least 52 writers and their families were trapped and could only leave if invited to an international peace conference. Slovene PEN planned to host such a conference and invite the writers and their families with the hope the U.N. Peacekeeping Force could provide protection for their exit. He urged other PEN centers to assist in finding residences and perhaps temporary teaching appointments or fellowships for these writers. He also delivered aid to trapped writers, aid gathered from other PEN Centers, donated to the Writers in Prison Committee Aid Fund and to PEN’s Emergency Fund run out of Amsterdam with Dutch PEN.

In an intersection of conflicts, the German and Finnish publishers of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses donated their proceeds from the book to PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. By the Vienna Congress, Rushdie had lived 1000 days under death threat. PEN continued its defense of Rushdie and its protest against the accompanying violence of the fatwa. The Japanese translator of Satanic Verses had been killed, and the Italian translator badly beaten. (Two years later the Norwegian publisher was shot three times and left for dead.) The bounty had increased on Rushdie, and there was allegedly a hit squad deployed in Western Europe to assassinate him.

One of many letters sent by International PEN to support Salman Rushdie and to protest the ongoing fatwa.

My personal engagement and memories during this period focused on work with the Writers in Prison Committee and to a lesser extent with the formation of the Women’s Committee, which I supported but which others were driving, and with the establishment of the International PEN Foundation which would be able to receive tax exempt funds for many of these PEN activities. After a discussion of the Foundation’s framework at the Paris Conference, including assurances that the Foundation would not interfere or challenge PEN’s governance, I presented the formal proposal at the Vienna Congress where the Assembly of Delegates approved the establishment of an International PEN Foundation. The Foundation received official charitable status in March 1992 and operated for the next decade until British charitable tax laws changed and a separate foundation was no longer necessary.

Also at the Vienna Congress the Women’s Network, which had formed at the Canadian Congress in 1989, gained approval as a standing committee of International PEN with assurances that men and women were welcome and would work together. Meredith Tax, a chief strategist and one of the founders, explained the committee would involve more women in the work of PEN at all levels and address problems that particularly affected women writers in developing countries and would enable women to know each other’s work, much of which was not translated. “The Women’s Committee will be a force to strengthen, not weaken PEN,” she assured the Assembly.

The eventual governance of the Women’s Committee included PEN members from around the world and its chair rotated to different regions. Each of PEN’s standing committees had its own governing structure. The Women’s Committee was unique in its inclusiveness, which had its own challenges, but which foreshadowed a more inclusive governing structure for PEN International. Twenty-eight PEN centers signed up for the committee with 70 delegates and members, including men, attending the initial meeting.

L to R: Moniika van Paemel, (Belgium Dutch-speaking PEN) and Meredith Tax (American PEN) at Women’s Committee Planning meeting at Canadian Congress, 1989

At the time International PEN’s leadership was all male. In its 80-year history International PEN had never had a woman President and only one woman International Secretary and few women as Committee chairs though in many centers of PEN there was a growing balance of men and women members and leaders. In 2015 novelist and poet Jennifer Clement was elected the first woman President of International PEN.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 8: Thresholds of Change…Passing the Torch

PEN Journey 2: The Fatwa

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments, though I’m not certain I can contain all these, but I hope this personal PEN journey may be of some interest.

It was President’s weekend in the US—between Lincoln and Washington’s birthday, coinciding with Valentine’s Day, 1989. I was President of PEN Center USA West and had just hired the Center’s first executive director ten days before. I’d been working hard with PEN and was also finishing a new novel, teaching and shepherding my 8 and 10-year old sons. For the first time in a year and a half my husband and I were going away for a long weekend without our children. He had also been working nonstop and had managed to clear his schedule.

On the plane to Colorado where we planned to ski, I read that Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses had been burned in Birmingham, England. The next day Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Rushdie. What was a fatwa? The Supreme Leader of Iran was calling for the murder of Rushdie wherever he was in the world, and he was offering a $6 million reward. As information about the fatwa developed, it also included a call for the death of whoever published The Satanic Verses.

I began making phone calls. This was a time before omnipresent cell phones so I had to find phones and numbers where people could reach me. (Usually our vacation dynamic was that my husband was on the phone.)

That first day I skied and wrote press releases on the ski lift and stopped at lodges on the mountain to use the pay phones to communicate with our new executive director. I’d ski another run then call the office again to answer questions from the press. What exactly was a fatwa, we were still asking? What did this mean for a writer? By the end of the day, I told my husband I had to return to LA.

“Can’t this wait?” he asked.

“No, it can’t,” I said.

Though a fatwa was a new concept, I understood, as did PEN members around the world, that a threshold had been crossed when a head of state issued a death warrant on a writer wherever he was in the world. Our two sons came out to be with my husband, and I returned to LA. Our board went into action as did PEN Centers around the globe to protest the fatwa. We organized a public event at the Los Angeles Times with writers and experts, an event which included readings from Rushdie’s book. Some were frightened by the threat, but most in PEN gathered. We contacted US government officials and began coordinating with global PEN centers, including American PEN in New York to confirm the support of writers for Rushdie and to protest Khomeini’s action.

Davis Dutton, center, of Dutton’s Books with some of his employees who voted to ignore the threats from Iran and stock “The Satanic Verses.”

Whatever the controversy over The Satanic Verses and its “insult” to Muslims, PEN was clear that the right of the writer to write without fear of death was primary.

The mobilization included discussions with bookstores to encourage them to keep the book on the shelves for many were quietly removing it. The fuller scope of our PEN’s actions at the time is described in the column below in the PEN Center USA West’s newsletter and in a story in the Los Angeles Times.

Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1989

Next Installment: PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN Journey 1: Engagement

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. As Vice President Emeritus of PEN International and former International Secretary, former Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, former President of PEN Center USA West, board member and Vice President of PEN America and the PEN/Faulkner Foundation, I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down some of the memories. I will try in digestible portions to recount moments, though I’m not certain how easily I can contain all these. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of some interest.

February 13, 1989: I was President of PEN Center USA West and on an airplane when I read that Salman Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses was being burned in Birmingham. The next day a fatwa was issued on Rushdie. What was a fatwa, we all asked at the time, as we, along with PEN Centers around the world, mobilized to protest that a head of state was ordering the murder of a writer wherever he was in the world.

November 10, 1995: As Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, I was standing vigil with others outside the Nigerian Embassy in Washington, D.C. when word spread that novelist and activist Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

October 7, 2006: My phone rang at 7:30 on Saturday morning. I was International Secretary of PEN International, and the International Writers in Prison Program Director was calling to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya had just been shot and killed in Moscow. We all knew Anna—I’d last had coffee with her at an airport in Macedonia. We worked with her on the situation of writers in Russia and Chechnya and had enormous respect for her knowledge and courage.

January 19, 2007: We were about to begin a PEN International board meeting in Vienna when a call came from Istanbul. Hrant Dink had just been shot and killed outside his newspaper office in Istanbul. Dink was an editor of an Armenian paper and a writer whom members of PEN knew well and worked with on freedom of expression issues in Turkey.

Most writers long active in PEN’s freedom-to-write work can tell you where they were when the news broke on each of these cases. They can tell you because the lives of these writers and many others have been critical in the struggle for freedom of expression around the world.