Posts Tagged ‘German PEN’

PEN JOURNEY: Introduction—Raising the Curtain: The Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and was asked by PEN International to write down memories. I have done so in 46 PEN Journeys and have been asked to write an introduction to these. Below is the introduction coming last, drawn in part from an earlier blog post of the same title, but not in this PEN Journey sequence.

“In a world where independent voices are increasingly stifled, PEN is not a luxury. It is a necessity.”—Novelist & poet Margaret Atwood, former President of PEN Canada

“…freedom of speech is no mere abstraction. Writers and journalists, who insist upon this freedom, and see in it the world’s best weapon against tyranny and corruption, know also that it is a freedom which must constantly be defended, or it will be lost.”—Novelist Salman Rushdie, PEN member

PEN International was started modestly 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catharine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others, conceived if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, they reasoned, at least among writers of Europe.

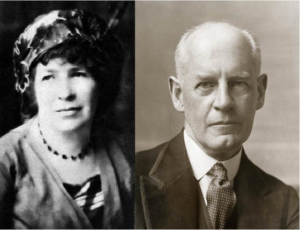

PEN Founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and first PEN President John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN [Poets, Essayists & Novelists—later expanding to Poets, Playwrights, Essayists, Editors and Novelists and now including a wide array of Nonfiction writers and Journalists] spread quickly. Clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, and the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. A decade later when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, he donated the prize money to International PEN. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace. Galsworthy spoke about the possibilities of a “League of Nations for Men and Women of Letters.”

Members of PEN began to gather at least once a year in 1923 with 11 Centers attending the first meeting. During the 1920’s writers regardless of nationality, culture, language or political opinion came together. As the political temperature rose in Europe, PEN insisted it was an apolitical organization though its role in the politics of nations was soon to be tested and ultimately landed not on a partisan or ideological platform but on a platform of ideals and principles.

At a tumultuous gathering at PEN’s 4th Congress in Berlin in 1926, tensions rose among the assembled writers, and the debate flared over the political versus non-political nature of PEN. Young German writers, including Bertolt Brecht, told Galsworthy that the German PEN Club didn’t represent the true face of German literature and argued that PEN could not ignore politics. Ernst Toller, a Jewish-German playwright, insisted PEN must take a stand.

After the Congress Galsworthy returned to London and holed up in the drawing room of PEN’s founder Catharine Scott where he worked on a formal statement to “serve as a touchstone of PEN action.” This statement included what became the first three articles of the PEN Charter. At the 1927 PEN Congress in Brussels, the document was approved and remains part of PEN’s Charter today, including the idea that “Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.” The third article of the Charter notes that PEN members “should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people and dispel all hatreds and champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

As the voices of National Socialism rose in Germany, PEN’s determination to remain apolitical was challenged though the determination to defend freedom of expression united most members. At the 1932 Congress in Budapest the Assembly of Delegates sent an appeal to all governments concerning religious and political prisoners, and Galsworthy issued a five-point statement, a document that would evolve into the fourth article of PEN’s Charter.

When Galsworthy died in January 1933, H.G. Wells took over as International PEN President. It was a time in which the Nazi Party in Germany was burning in bonfires thousands of books they deemed “impure” and hostile to their ideology. At PEN’s 1933 Congress in Dubrovnik, H.G. Wells and the PEN Assembly launched a campaign against the burning of books by the Nazis and voted to reaffirm the Galsworthy resolution. German PEN, which had failed to protest the book burnings, attended the Congress and tried to keep Ernst Toller, a Jew, from speaking. Some members supported German PEN, but the overwhelming majority reaffirmed the principles they had just voted on the previous day. The German delegation walked out of the Congress and out of PEN and didn’t return until after World War II. Their membership was rescinded. “If German PEN has been reconstructed in accordance with nationalistic ideas, it must be expelled,” the PEN statement read. During World War II PEN continued to defend the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. (Today German PEN is one of PEN’s active centers, especially on issues of freedom of expression and assistance to exiled writers.)

PEN was one of the first nongovernmental organizations and the first human rights organization in the 20th century. PEN’s Charter, which developed over two decades, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II. In 1949 PEN was granted consultative status at the United Nations as “representative of the writers of the world,” and is today the only literary organization with formal consultative status with UNESCO.

In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in more than 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries, defend linguistic rights and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia in the late 1980’s and in other countries of the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar where a former prisoner of conscience was instrumental in forming a center there and was its first President. A PEN center is a refuge for writers in many countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

For more than 35 years I have been engaged with PEN, as a member, as the President of one of PEN’s largest centers, PEN Center USA West during the year of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie and Tiananmen Square, as Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), as International Secretary (2004-2007), and continuing as an International Vice President since 1996. I’ve also served on the Board and as Vice President of PEN America (2008-2015). I lived for six years in London, where PEN International is headquartered.

In the run-up to PEN’s Centenary, I was asked if I would write an account of PEN’s history as I’d seen it. I began by posting a blog twice a month, taking on small slices of the history in each narrative. This serial blog of PEN Journeys recounts PEN’s history as I’ve witnessed it as well as history of the period and personal history during those years. The narratives are framed by the times, featuring writers, including the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, the protests in Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall—PEN members or future PEN members were central in all these events—the collapse of the Soviet Union and the formation of PEN Centers there; the opening up of Eastern Europe with its PEN centers; the release of PEN “main case” Václav Havel and his ascendency to the Presidency of Czechoslovakia; the mobilization of Turkish PEN members in opposition to recurring authoritarian governments; PEN’s mission to Cuba; PEN’s protests over killings and impunity in Mexico; protests and gatherings in Hong Kong on behalf of imprisoned Chinese writers; the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Peace to PEN member and Independent Chinese PEN Center founder and President Liu Xiaobo.

PEN and its members have played a pivotal role in defending freedom of expression around the world, in challenging systems that trap citizens, and in at least two instances, in taking on the presidencies of the new democracies that emerged. The PEN Charter, which sets out the principles and ideals, has united the global organization and guided its members who have often been at the forefront or in the wings of important historical moments—celebrated and outspoken writers like Václav Havel, Nadine Gordimer, Margaret Atwood, Orhan Pamuk, Yaşar Kemal, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Koigi wa Wamwere, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Arthur Miller, Anna Politkovskaya, Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Carlos Fuentes, Liu Xiaobo. The list is long, and I have had the privilege of interacting with many of them in PEN and also with hundreds of perhaps lesser known, but courageous writers who have stood watch and engaged.

The view of PEN Journey is global though the work is often local. As well as chronicling global events and personal history, PEN Journey recounts the shaping and re-imagining of this sprawling nongovernmental organization, one of the largest in terms of geographic reach. PEN has had to evolve and re-shape itself to serve its 155 autonomous centers. With at least 40,000 members around the globe in more than 100 countries, there are many stories others might tell, but this narrative is a close-up view of a period of time and of the writers who continue to work together in the belief that the world for all its differences and complexities can aspire to and perhaps even achieve “the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”* [*PEN Charter]

Because I tended not to throw away documents over the decades, I have an extensive paper as well as digital archive which I used to refresh memories and document facts. As I dug through files, I came across a speech I’d given which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman speaking at PEN International Conference on Cultural Diversity in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005

The talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is ongoing. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King is quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

From Diyarbakir Conference:

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through PEN’s 141 centers in 99 countries. [Now 155 centers in over 100 countries.] They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see for himself this ancient city, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together.

–Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International, March 2005