Posts Tagged ‘Macedonian PEN’

PEN Journey 27: San Miguel de Allende and Other Destinations—PEN’s Work Between Congresses

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Over the years I’ve used various metaphors to describe PEN International—a giant wheel with 140+ spokes that reach out into the corners of the globe. A vast orchestra with the string, woodwind, brass and percussion sections scattered across the map, directed by local conductors and the Secretariat in London.

PEN’s core is an idea, codified in its Charter, acted upon by writers around the world organized into PEN centers. These writers and centers gather intensity as they work together.

PEN International logo in 2002

Writers in a country or region or language are empowered to work as a center of PEN by the whole body of centers—the Assembly of Delegates—which vote on a center’s membership at PEN’s annual Congresses. During the months in between, PEN centers act both individually and collectively—celebrating and presenting literature in the many cultures and languages, mobilizing on issues of freedom of expression, acting to preserve and celebrate languages and translation, in particular minority languages, discussing and debating issues of peace, addressing the situation of women writers, and assisting and protecting writers who find themselves in exile. All of this activity between the annual Congresses occurs in the PEN centers and in the work of PEN International’s standing committees and at regional conferences which convene during the year.

I take a moment here to set out this template because in the PEN Journeys I’ve been focusing in large part on PEN’s annual Congresses. Yet the heart and soul of the organization resides in its centers and the individual members, most of whom never attend a PEN International Congress.

Some centers host the meetings of PEN’s standing committees. Slovene PEN has long hosted the annual Peace Committee meeting in Bled, Slovenia (PEN Journey 14). Until recently Macedonian and Catalan PEN have alternated hosting the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee’s annual meetings either in Ohrid or Barcelona. The Women’s Committee set a new paradigm when it formed in 1991 by rotating its chair to different regions of the world and hosting its meetings there though recently because of costs, the Women’s Committee has held its meetings along with other committees, usually with the Peace Committee in Bled. As I’ve written in earlier posts (Journey 17 and 23) the Writers in Prison Committee began holding a biennial meeting in 1996, hosted by different PEN Centers. In recent years to share costs, the Writers in Prison Committee (WIPC) has teamed up with ICORN (International Cities of Refuge Network) to hold its biennial meeting in different countries. The recent 2018 WIPC meeting was held aboard a docked cruise ship in the Rotterdam Harbor.

Bellas Artes Center, San Miguel de Allende, site of PEN WIPC conference, November 2002

In November 2002 the fourth WIPC meeting gathered in San Miguel de Allende, hosted by the PEN Center there in the charming old colonial town 170 miles from Mexico City where the 2003 PEN Congress would convene the following year. Forty-three PEN members from 25 centers from six continents gathered at the Bellas Artes center for a three-day conference followed by a meeting of the PEN Americas Regional Conference with the Latin American PEN Centers.

At the Bellas Artes center, originally the cloister of a convent, and in the Teatro del Artes PEN members met in workshops to review sources and methods as related to the threats of terrorism and anti-terror laws to freedom of expression, to review campaign techniques, PEN’s work at the United Nations, missions, regional networks, exile and asylum issues, borderline cases and finally strategies for the future. PEN’s WIPC set out to research a report in consultation with other organizations on the effect of anti-terrorism measures worldwide on freedom of expression, a report that would be presented at the 2003 PEN Congress.

In San Miguel PEN’s WIPC launched a report and a campaign “Freedom of Expression and Impunity Campaign” with an epigraph from Helen Mack, sister of anthropologist Myrna Mack, who was murdered in 1990 on orders carried out by the Guatemalan military. Helen Mack wrote:

Through my experience as co-plaintiff in the on-going trial to resolve the murder of my sister, Myrna Mack, I have seen impunity up close, along every step of this tortuous path in search of justice. I have felt it when essential information has been denied that would determine individual criminal responsibility; when judges and witnesses have been threatened; when the lawyers for the accused military officials use the same constitutional guarantees of due process in order to obstruct judicial procedures; and when my family, my lawyers, my colleagues and I have been threatened or been victims of campaigns to discredit us. In every action that is oriented toward generating impunity, one can clearly see the hand of agents of the State who use the same judicial and security institutions to pervert, once again, the goal of reparation through judicial means as well as the right to the truth and to justice.

PEN International Impunity Report, launched at 2002 WIPC Conference, San Miguel de Allende

The Impunity report focused on Colombia, Iran, Mexico, Philippines, and Russia but PEN’s ongoing campaign targeted the issue wherever it occurred in the world.

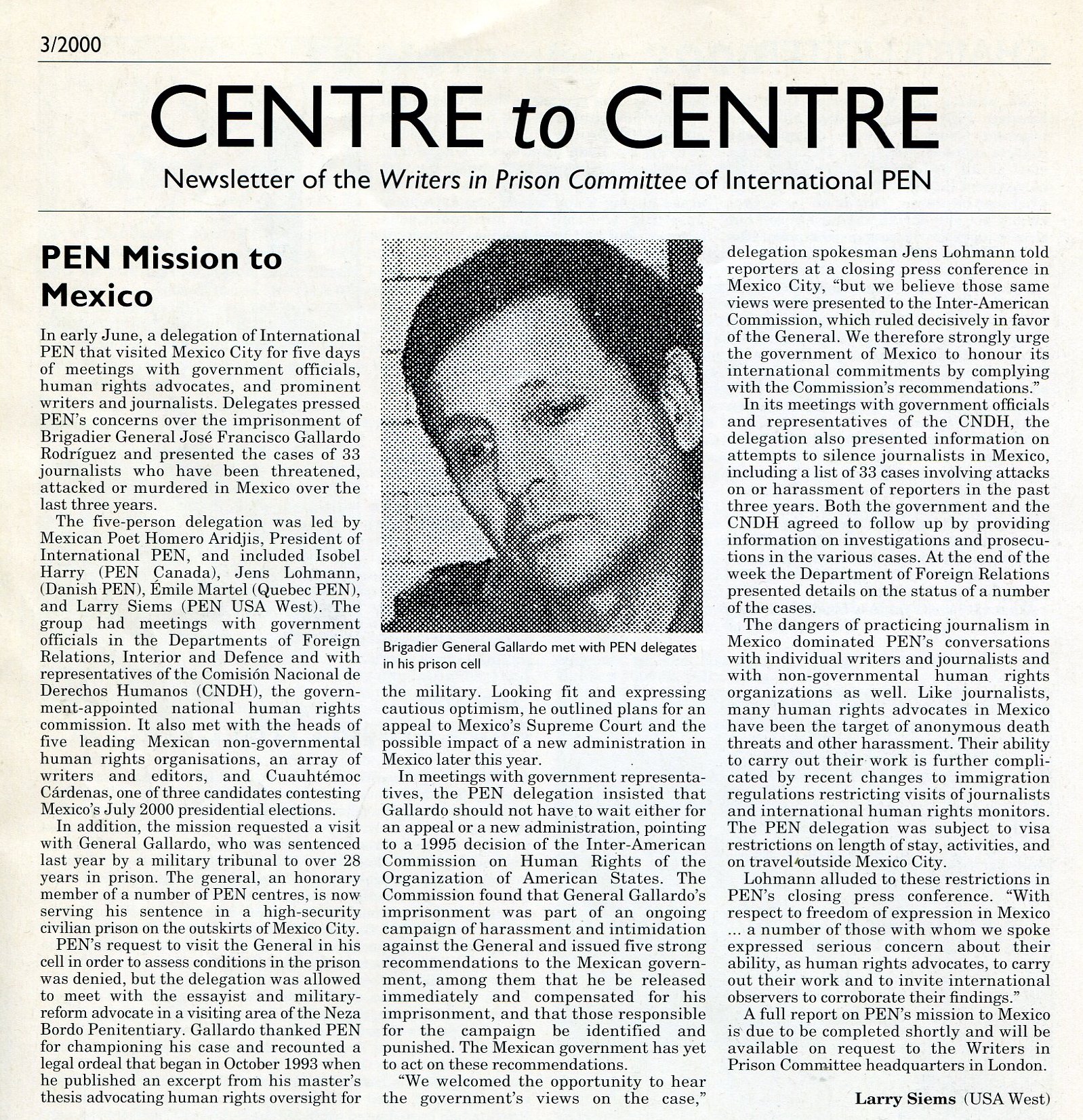

Addressing the 2002 WIPC Conference and the Latin American Network was Brigadier General José Gallardo Rodriguez. At the Macedonian Congress earlier in the year PEN International President Homero Aridjis had reported on General Gallardo’s release. “Last February, I was invited to testify on behalf of PEN on General José Francisco Gallardo’s case, as one of three witnesses scheduled to appear before the Inter-American Court on Human Rights at a hearing in Costa Rica,” Homero said. “A few days before the hearing at which the Mexican Government was ordered to appear, he [Gallardo] was unexpectedly pardoned and released from jail, nine years after his arrest and imprisonment following the publication in the magazine Forum of an excerpt of his masters’ thesis about the need for a military ombudsman in Mexico. General Gallardo’s release was an important victory for freedom of speech and a significant advance of justice in Mexico. PEN Centers worldwide who defended Gallardo’s cause for eight years now celebrate the liberation of a Mexican Dreyfus.”

General Gallardo thanked International PEN for its invaluable support for having campaigned on his behalf, and he assured that he would continue to press for the creation of a military ombudsman.

PEN WIPC newsletter 2000 on case of General José Gallardo Rodriguez

The Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression for the Organization of American States also participated on a panel on Corruption and the Writer, focusing on the problem of impunity, its link to corruption, its effect on free speech and the role of the writer in combating these problems.

Noting the increasing workload of the WIPC and the fact that the staff and budget had not grown at the same rate, several members suggested a Steering Committee of five individuals/centers be formed to assist the WIPC headquarters and work directly with committee chair Eugene Schoulgin and the WiPC staff led by Sara Whyatt. This group would formulate a strategy for the next three years, help define priorities and address the resources needed to achieve the goals. The proposal was accepted, and Isobel Harry (Canadian PEN), Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN), Jens Lohmann (Danish PEN), Lucy Popescu (English PEN) and Larry Siems (American PEN) formed the Planning Group. Their goal was to produce with the staff a plan that would be vetted by all WiPC members and approved at the Mexico Congress.

At the same time PEN International as a whole was undergoing a major strategic planning process. As the century turned, PEN International was in the midst of restructuring itself both to develop a more democratic governance system and also to address its rapid growth and funding challenges. In this process American PEN was an important actor, along with the Scandinavian and Japanese centers. American PEN, located in New York, was the largest of PEN’s centers and contributed more dues than any other center, but it had not hosted an International Congress since 1986 and did not host any of the international conferences or committee meetings. It had launched a World Voices Festival after 9/11 to bring international writers to the U.S. but this was an American PEN, not an International PEN, activity. However, with the assistance of two former American PEN presidents—Edmund (Mike) Keeley and Michael Scammell and American PEN Executive Director Michael Roberts and former PEN USA West President and International PEN Board member Eric Lax, the American contingent stepped up to raise funds from American foundations, including the Mellon Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation to assist International PEN in a major strategic planning initiative. This consisted of several preliminary conferences in London and a final gathering at the Rockefeller estate in Bellagio, Italy.

The Americans, particularly Mike Roberts, PEN America’s Executive Director, understood that American PEN was only as strong as the whole body of PEN which at the moment had a very small hub or Secretariat for a very large wheel of 140 spokes. The core needed strengthening both structurally and financially. International Secretary Terry Carlbom, International PEN President Homero Aridjis, Deputy Vice Chair of the Board Carles Torner and the whole Board of PEN International, along with members of the board of the PEN International Foundation, Standing Committee Chairs, and several Vice Presidents agreed and committed to the strategic planning process.

During the last decades PEN had depended on funds from its centers and from UNESCO and from SIDA, the Swedish Development Association and a few other funders, but the world was changing and with it the sources of funding. U.N. organizations like UNESCO were under siege. Government funding for European and East European cultural organizations was evaporating; the same was true for other PEN centers. The challenge for PEN was structural and financial. No one knew what the 21st century would bring, but most everyone understood it would not be the same.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 28: Bellagio: Looking Forward—PEN for the 21st Century

PEN Journey 26: Macedonia—Old and New Millennium

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I remember diving from a rowboat into Lake Ohrid and swimming in pristine water. I love to swim but never did so at PEN Congresses. However, the 68th Congress was held on one of Europe’s oldest—3 million years old—and deepest lakes which floated in the mountainous region between North Macedonia and eastern Albania. The water was the cleanest I had ever seen or felt. I swam without looking back until finally, I heard a voice from the boat shouting, “Come back! You’re almost in Albania!”

Moments before Isobel Harry (l) (Canadian PEN) and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (r) (American PEN) dive into Lake Ohrid for a swim between meetings at the 68th PEN Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia in 2002

Albania, or rather the Albanian Liberation Army, a paramilitary organization, had recently been in conflict in Macedonia and was the reason PEN’s Congress there had been postponed the year before. (PEN Journey 25)

Swimming with me was my friend Isobel Harry, Executive Director of Canadian PEN, and in the boat sat Cecilia Balcazar from Colombian PEN and another PEN member. They watched over us in this break from the PEN meetings. My memories of the 2002 PEN Macedonia Congress include intense meetings of the Assembly in the Congress Hall of the old Soviet-style Metropol Hotel and neighboring Bellevue Hotel conference center and relaxed gatherings afterwards at lakeside cafes in the town of Ohrid, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

PEN colleagues at a lakeside cafe during the PEN Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia. (L to R) Dixie Willis and Sara Whyatt (WiPC staff), Susie Nicklin (English PEN), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN & WiPC Chair), PEN member, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Vice President & American PEN), Niels Barfoed (Danish PEN), Isobel Harry (Canadian PEN), Fawzia Assaad (Swiss Romand PEN), Victoria Glendinning (English PEN), Carles Torner (PEN Board & Catalan PEN)

In the evenings we gathered for literary events with UNESCO-like titles—The Future of Language/Language of the Future and Borders of Freedom/Freedom of Borders. These were also the themes of the Congress. There was music and poetry in Macedonian and other languages I didn’t understand, recited in cavernous, shadowy chambers, including in the ancient Cathedral Church of St. Sophia, a structure from medieval times, rebuilt in the 10th century. Its frescoes still adorned the walls from Byzantine times in the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries and had been restored after the church was converted to a mosque during the Ottoman Empire.

While current politics and conflicts occupied the daytime work of PEN, history suffused the gathering. Civilization in Ohrid dated to 353 BC when the town had been known as “the city of light.”

Cathedral Church of St. Sophia in Ohrid

“The old millennium, especially in ‘old’ Europe, should, I believe, be left behind with all its anachronistic boundaries—geographical, historical, racial, ethnic, state, linguistic, religious and cultural—and give way to the unfolding of the new millennium, to its open-mindedness and tolerance,” Dimitar Baševski, President of Macedonian PEN, wrote in his introduction to the Congress. “For generations we in Macedonia have lived with a creed according to which culture and not warfare or power is perceived as the field for competitiveness among nations. The aims of the World Congress of International P.E.N. in 2002 perfectly correspond with the spirit of this creed.”

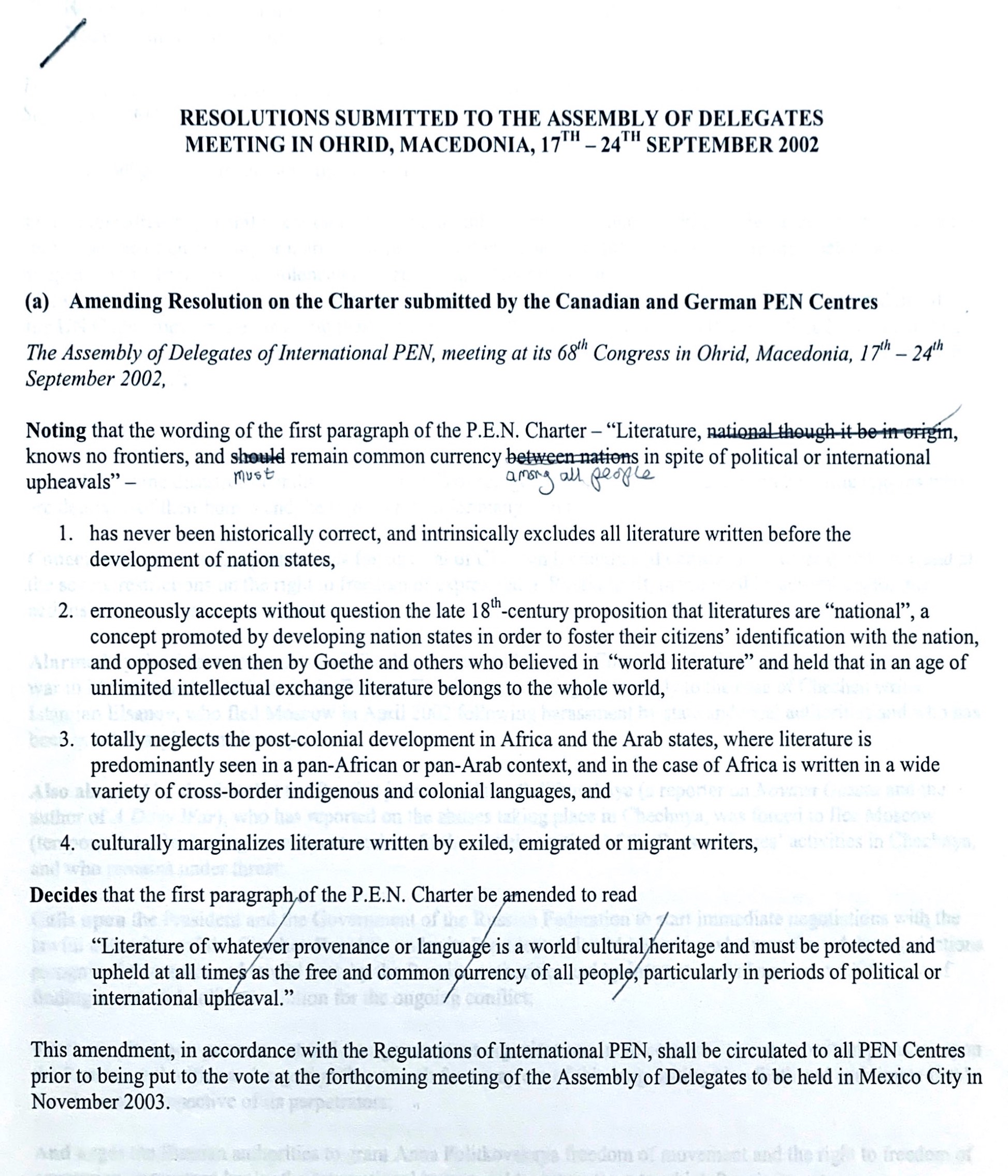

Over 300 people from 69 PEN Centers gathered in the hills of this North Macedonian city for the 68th World Congress. The Congress’ work included the activities and reports of PEN’s committees—Writers in Prison, Peace, Translation and Linguistic Rights, Women’s, Exile Network—and the PEN Foundation, PEN International Magazine, and PEN Emergency Fund. There was a proposed revision to PEN’s Charter removing the concept of literature as being national in origin; there was the introduction of new centers, the dissolution of inactive centers and the elections for the Board, Vice Presidents, and Search Committee. There was a report from the International Secretary on the renewal of PEN’s “formal consultative relations” with UNESCO for a further six years, a step that acknowledged PEN as the only voluntary organization and the only literary organization in this category and one of only 12 organizations with a “Framework Agreement.” PEN had also been reclassified as a Category II organization with ECOSOC (United Nations Economic and Social Council) which included organizations with “special competence in specific areas” such as Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, a category that reflected PEN’s status and contribution as the only world writers organization within the UN system. At PEN’s Assembly of Delegates attention was called to a dozen PEN conferences—last year’s and the year ahead—and finally the Assembly passed Resolutions from the Writers in Prison Committee and Peace Committee on the situations in Russia and Chechnya, Russia itself, the Middle East, Belorussia, China, Colombia, Cuba, Iran, Turkey, Zimbabwe, Uighur Writers, and Tatarstan

The aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on the United States the year before remained a focus that was altering the security landscape for nations around the world and for writers. PEN President Homero Aridjis observed, “Today our world is teetering on the brink of war.” He added, “In search of security, there have been encroachments on privacy and intrusive measures threatening freedom of expression and the right to dissent and criticize, but the global reach of information seems to have accelerated, proof of which is the current effort by the Chinese government to block its citizens’ access to the search-engine Google.”

“How can PEN and writers bring about positive changes?” he asked. “For a start, we could promote freedom of expression in Afghanistan. Not that long ago we were signing Internet petitions protesting against the treatment of women by the inhumane Taliban regime and begging the Taliban not to dynamite the colossal Buddhas of Bamiyan. Now I ask you to help me identify and approach Afghani writers who would be willing to found a PEN Center in Afghanistan and to try and find ways of giving this fledgling Center the means to thrive.”

[With the help of Norwegian PEN and others, an Afghan PEN Center was in fact founded with men and women writers from all ethnic groups and was voted into PEN at the 69th Congress the following year in Mexico. Writers in Prison Committee Chair Eugene Schoulgin played an instrumental role in working with and facilitating support for the Afghan writers.]

At the Macedonia Congress Eugene reported, “In my speech in London last November I mentioned the threats to the freedom of expression I feared that would follow the events of 9/11 in the US. What has happened last year has unfortunately proved these fears were well founded. Today over 40 countries have imposed new legislation on their populations which clearly weaken their human rights. New Anti-terror laws have been established in Canada, USA, UK, France, EU as a whole, Jordan, India and New Zealand. Terrorism laws expanded on Cuba and on Italy and in Colombia, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Israel, Russia, Uzbekistan, China and in the Philippines, and terror laws have been used as an excuse to crack down on the opposition and on minorities inside their regions. This in combination with the threats of a new war on Iraq makes the present situation extremely worrying, and will most certainly give us in the WiPC reason to be even more vigilant in the year to come.”

Visiting the WiPC Committee at the Congress were two former PEN main cases—Eşber Yağmurdereli, Turkish poet/dramatist and lawyer, who was blind and spent 14 years in prison and whom a number of us had met in Istanbul at a Freedom of Expression Initiative a few years before and Flora Brovina, a Kosovair/Albanian poet and doctor who had been abducted by Serbian troops and imprisoned in Belgrade during the NATO bombing. Flora’s son had contacted PEN which sent out an urgent appeal about her abduction. I had met her husband and family when I visited Pristina, Kosovo the year before with the International Crisis Group while she was still in prison. This was the first time I met Flora, who had become an internationally celebrated case and was a member the country’s Assembly. She told the Writers in Prison Committee that every letter sent to the prison by PEN served as another attempt to tear down the walls of the prison.

Esber Yagmurdereli said at present there were around 10,000 prisoners accused of being “terrorists,” but 90% of these should be considered prisoners of conscience, and many were simply students. “On 19 December 2000, the 20th day of the protest, I was playing chess with my friend in my cell,” he said. “He was a university student named Irfan. He was my son’s age–21 or 23 years old. He defeated me three tims. He said you are 60 years old. There are so many of us whose cases ar not covered in the press, but you do get attention. We need you as much as you need us. Then came the teargas. The protests took three yours. I myself lost consciousness and came to about an hour later. I learned that 32 people had been killed–burned to death. I learned that my friend Irfan was one of them.”

Russian journalist Anna Politkovskya also attended the Macedonian Congress. She told the WIPC meeting that she got threats from criminals, military and government. “I could stay in Vienna or elsewhere in the West, but it is my decision to be in Russia because I understand more than other people that if I couldn’t write articles or give radio talks, there would be no information about Chechnya,” she said. “Because travel to Chechnya is illegal, I need to prepare my trips as if I were a spy. I have to be strong, as far as I can. My children are in Moscow, and they are also threatened. ” My last meeting with Anna was sharing thick coffee at a tiny airport café in Skopje on our way home from the Congress.

Resolution for change in wording of PEN’s Charter; amended wording, noted and approved, proposed by English PEN president Victoria Glendinning. Final proposal and approval to take place at Mexico Congress in 2003.

In addition to its traditional work, International PEN was proceeding with modernizing its governance and structure, led by International Secretary Terry Carlbom and the Board of PEN. Deputy Vice Chair of the Board Carles Torner reported that this included the restructuring of PEN and the PEN Foundation as British charitable tax law was changing; also new roles for the Vice Presidents were being considered; a modest change in the Charter was proposed for this Assembly to be confirmed at the next year’s Congress in Mexico, and the Treasurer was proposing a new international dues structure with a graded system, raising dues for centers from wealthier economies and reducing dues for others, based on the World Bank system of four categories. The change in the dues structure was unanimously approved.

Elections at the Congress included two new Vice Presidents Lucina Kathmann (San Miguel Allende PEN) and Boris Novak (Slovene PEN) and new Board members Takeaki Hori (Japan PEN), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN) and Elisabeth Nordgren (Finnish PEN).

“We are at the end of the first mandate of the first Board elected three years ago during the Warsaw Congress under the new Regulations.” Carles reported. “…we now have a real capacity for collective decision-making between Congresses…we are noticing that the transformation we dreamed of six years ago, when the new structuring of International PEN started, has taken place. There are more people involved in the work of International PEN, and each person represents a specific sensitivity within our international community…and we are better prepared to achieve our task now and in the future.”

The modernization and reform of governance also applied to PEN’s more than 130 centers with agreement that new centers from unrepresented parts of the world needed to be developed and centers that no longer functioned or worked in harmony with PEN’s Charter should be disbanded though there was often reluctance among PEN members to close a center.

At the Macedonia Congress, a particular PEN-like debate arose over the Langue d’Oc Center which no longer functioned. Langue d’Oc, or the Language of the Troubadours, was still spoken in a region in the South of France, in part of Italy and in one valley in Spain. The center’s president, whose name was the same as a great literary character, had worked on PEN’s Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights with PEN’s Committee on Translation and Linguistic Rights half a dozen years before, and one member was still eager to keep the center going as a cause of minority languages. But the elderly outgoing President was not able to help, according to Jane Spender, PEN’s Administrative Director, who communicated or tried to communicate, with these centers. The center no longer functioned, had no office or contacts who replied, she reported. Before the center was declared closed, however, former International Secretary Alexander Blokh proposed that it be declared dormant and during the ensuing year French PEN writers who knew some of the members would “try to wake them up.” The Portuguese PEN delegate also offered to help as did the Esperanto, Slovene and Galician delegates. A similar lifeline was given to the inactive Welsh center by English PEN who agreed to perform the same role.

At PEN’s Congress the following year in Mexico, the interventions confirmed that after a year of dormancy neither center had rallied and so the Assembly voted to close the centers. In both cases new writers then came forward, and a few years later a new and active Welsh Center and Langue d’Oc Center formed and were elected back into PEN’s Assembly.

At the Macedonia Congress three brand new centers—Kyrghyz, Sierra Leone, and Tibet—joined the PEN family. It was in this fashion that PEN International pruned, renewed and broadened its base in civil society among nations and cultures and languages.

Lake Ohrid in the hills of North Macedonia between Macedonia and eastern Albania

Next Installment: PEN Journey 27: San Miguel Allende and Other Destinations–PEN’s Work Between Congresses