Posts Tagged ‘Slovene PEN’

PEN Journey 27: San Miguel de Allende and Other Destinations—PEN’s Work Between Congresses

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Over the years I’ve used various metaphors to describe PEN International—a giant wheel with 140+ spokes that reach out into the corners of the globe. A vast orchestra with the string, woodwind, brass and percussion sections scattered across the map, directed by local conductors and the Secretariat in London.

PEN’s core is an idea, codified in its Charter, acted upon by writers around the world organized into PEN centers. These writers and centers gather intensity as they work together.

PEN International logo in 2002

Writers in a country or region or language are empowered to work as a center of PEN by the whole body of centers—the Assembly of Delegates—which vote on a center’s membership at PEN’s annual Congresses. During the months in between, PEN centers act both individually and collectively—celebrating and presenting literature in the many cultures and languages, mobilizing on issues of freedom of expression, acting to preserve and celebrate languages and translation, in particular minority languages, discussing and debating issues of peace, addressing the situation of women writers, and assisting and protecting writers who find themselves in exile. All of this activity between the annual Congresses occurs in the PEN centers and in the work of PEN International’s standing committees and at regional conferences which convene during the year.

I take a moment here to set out this template because in the PEN Journeys I’ve been focusing in large part on PEN’s annual Congresses. Yet the heart and soul of the organization resides in its centers and the individual members, most of whom never attend a PEN International Congress.

Some centers host the meetings of PEN’s standing committees. Slovene PEN has long hosted the annual Peace Committee meeting in Bled, Slovenia (PEN Journey 14). Until recently Macedonian and Catalan PEN have alternated hosting the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee’s annual meetings either in Ohrid or Barcelona. The Women’s Committee set a new paradigm when it formed in 1991 by rotating its chair to different regions of the world and hosting its meetings there though recently because of costs, the Women’s Committee has held its meetings along with other committees, usually with the Peace Committee in Bled. As I’ve written in earlier posts (Journey 17 and 23) the Writers in Prison Committee began holding a biennial meeting in 1996, hosted by different PEN Centers. In recent years to share costs, the Writers in Prison Committee (WIPC) has teamed up with ICORN (International Cities of Refuge Network) to hold its biennial meeting in different countries. The recent 2018 WIPC meeting was held aboard a docked cruise ship in the Rotterdam Harbor.

Bellas Artes Center, San Miguel de Allende, site of PEN WIPC conference, November 2002

In November 2002 the fourth WIPC meeting gathered in San Miguel de Allende, hosted by the PEN Center there in the charming old colonial town 170 miles from Mexico City where the 2003 PEN Congress would convene the following year. Forty-three PEN members from 25 centers from six continents gathered at the Bellas Artes center for a three-day conference followed by a meeting of the PEN Americas Regional Conference with the Latin American PEN Centers.

At the Bellas Artes center, originally the cloister of a convent, and in the Teatro del Artes PEN members met in workshops to review sources and methods as related to the threats of terrorism and anti-terror laws to freedom of expression, to review campaign techniques, PEN’s work at the United Nations, missions, regional networks, exile and asylum issues, borderline cases and finally strategies for the future. PEN’s WIPC set out to research a report in consultation with other organizations on the effect of anti-terrorism measures worldwide on freedom of expression, a report that would be presented at the 2003 PEN Congress.

In San Miguel PEN’s WIPC launched a report and a campaign “Freedom of Expression and Impunity Campaign” with an epigraph from Helen Mack, sister of anthropologist Myrna Mack, who was murdered in 1990 on orders carried out by the Guatemalan military. Helen Mack wrote:

Through my experience as co-plaintiff in the on-going trial to resolve the murder of my sister, Myrna Mack, I have seen impunity up close, along every step of this tortuous path in search of justice. I have felt it when essential information has been denied that would determine individual criminal responsibility; when judges and witnesses have been threatened; when the lawyers for the accused military officials use the same constitutional guarantees of due process in order to obstruct judicial procedures; and when my family, my lawyers, my colleagues and I have been threatened or been victims of campaigns to discredit us. In every action that is oriented toward generating impunity, one can clearly see the hand of agents of the State who use the same judicial and security institutions to pervert, once again, the goal of reparation through judicial means as well as the right to the truth and to justice.

PEN International Impunity Report, launched at 2002 WIPC Conference, San Miguel de Allende

The Impunity report focused on Colombia, Iran, Mexico, Philippines, and Russia but PEN’s ongoing campaign targeted the issue wherever it occurred in the world.

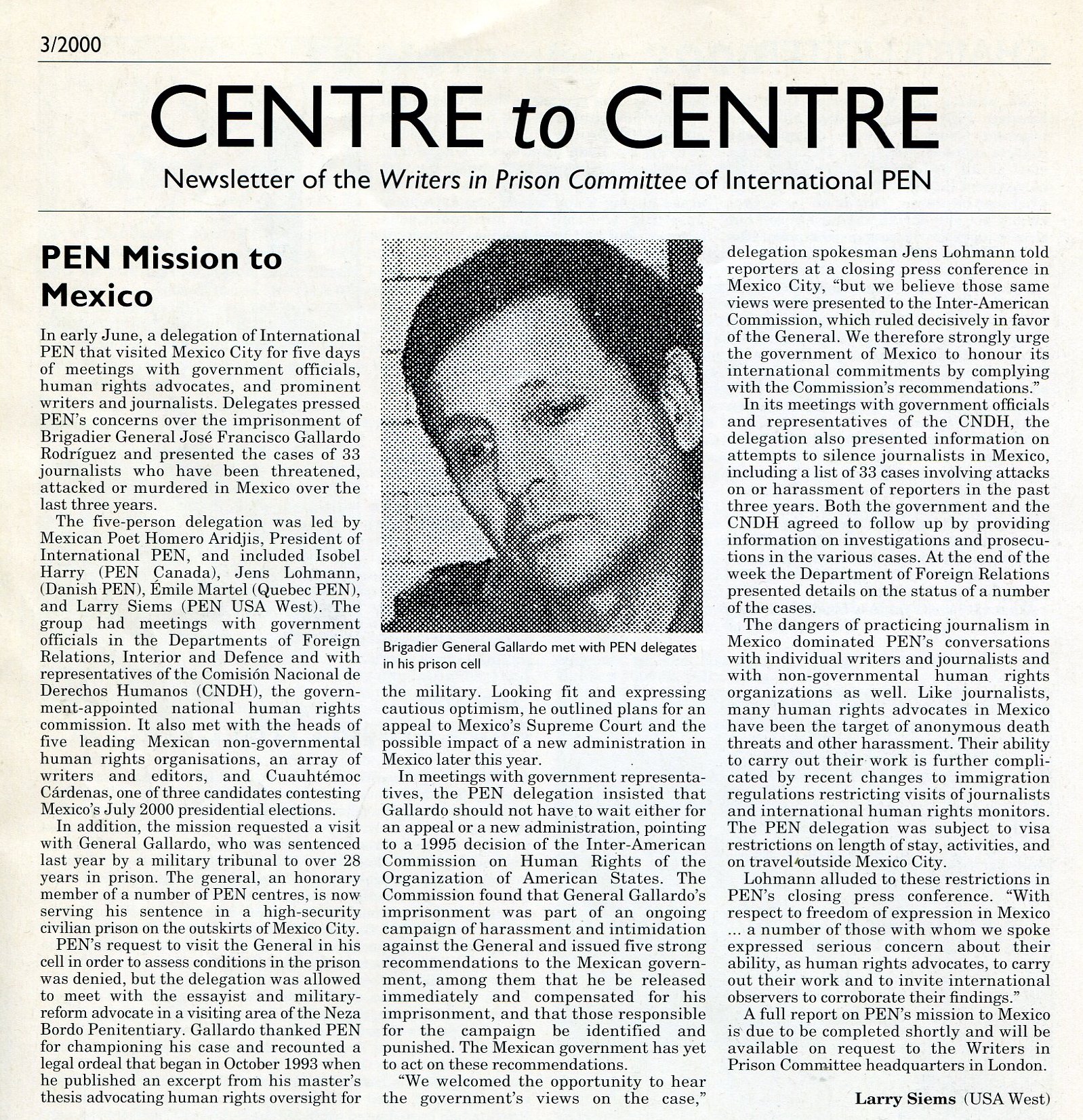

Addressing the 2002 WIPC Conference and the Latin American Network was Brigadier General José Gallardo Rodriguez. At the Macedonian Congress earlier in the year PEN International President Homero Aridjis had reported on General Gallardo’s release. “Last February, I was invited to testify on behalf of PEN on General José Francisco Gallardo’s case, as one of three witnesses scheduled to appear before the Inter-American Court on Human Rights at a hearing in Costa Rica,” Homero said. “A few days before the hearing at which the Mexican Government was ordered to appear, he [Gallardo] was unexpectedly pardoned and released from jail, nine years after his arrest and imprisonment following the publication in the magazine Forum of an excerpt of his masters’ thesis about the need for a military ombudsman in Mexico. General Gallardo’s release was an important victory for freedom of speech and a significant advance of justice in Mexico. PEN Centers worldwide who defended Gallardo’s cause for eight years now celebrate the liberation of a Mexican Dreyfus.”

General Gallardo thanked International PEN for its invaluable support for having campaigned on his behalf, and he assured that he would continue to press for the creation of a military ombudsman.

PEN WIPC newsletter 2000 on case of General José Gallardo Rodriguez

The Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression for the Organization of American States also participated on a panel on Corruption and the Writer, focusing on the problem of impunity, its link to corruption, its effect on free speech and the role of the writer in combating these problems.

Noting the increasing workload of the WIPC and the fact that the staff and budget had not grown at the same rate, several members suggested a Steering Committee of five individuals/centers be formed to assist the WIPC headquarters and work directly with committee chair Eugene Schoulgin and the WiPC staff led by Sara Whyatt. This group would formulate a strategy for the next three years, help define priorities and address the resources needed to achieve the goals. The proposal was accepted, and Isobel Harry (Canadian PEN), Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN), Jens Lohmann (Danish PEN), Lucy Popescu (English PEN) and Larry Siems (American PEN) formed the Planning Group. Their goal was to produce with the staff a plan that would be vetted by all WiPC members and approved at the Mexico Congress.

At the same time PEN International as a whole was undergoing a major strategic planning process. As the century turned, PEN International was in the midst of restructuring itself both to develop a more democratic governance system and also to address its rapid growth and funding challenges. In this process American PEN was an important actor, along with the Scandinavian and Japanese centers. American PEN, located in New York, was the largest of PEN’s centers and contributed more dues than any other center, but it had not hosted an International Congress since 1986 and did not host any of the international conferences or committee meetings. It had launched a World Voices Festival after 9/11 to bring international writers to the U.S. but this was an American PEN, not an International PEN, activity. However, with the assistance of two former American PEN presidents—Edmund (Mike) Keeley and Michael Scammell and American PEN Executive Director Michael Roberts and former PEN USA West President and International PEN Board member Eric Lax, the American contingent stepped up to raise funds from American foundations, including the Mellon Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation to assist International PEN in a major strategic planning initiative. This consisted of several preliminary conferences in London and a final gathering at the Rockefeller estate in Bellagio, Italy.

The Americans, particularly Mike Roberts, PEN America’s Executive Director, understood that American PEN was only as strong as the whole body of PEN which at the moment had a very small hub or Secretariat for a very large wheel of 140 spokes. The core needed strengthening both structurally and financially. International Secretary Terry Carlbom, International PEN President Homero Aridjis, Deputy Vice Chair of the Board Carles Torner and the whole Board of PEN International, along with members of the board of the PEN International Foundation, Standing Committee Chairs, and several Vice Presidents agreed and committed to the strategic planning process.

During the last decades PEN had depended on funds from its centers and from UNESCO and from SIDA, the Swedish Development Association and a few other funders, but the world was changing and with it the sources of funding. U.N. organizations like UNESCO were under siege. Government funding for European and East European cultural organizations was evaporating; the same was true for other PEN centers. The challenge for PEN was structural and financial. No one knew what the 21st century would bring, but most everyone understood it would not be the same.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 28: Bellagio: Looking Forward—PEN for the 21st Century

PEN Journey 14: Speaking Out: PEN’s Peace Committee and Exile Network

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

With a blue glacial lake surrounded by the Alps, a small island in the center with an ancient church with a Wishing Bell that rang out and promised fulfillment for the wishers, with a castle perched atop a hillside—with beauty and history intertwined through the landscape, Bled, Slovenia offered a stunning venue for PEN International’s Peace Committee meetings.

Bled, Slovenia

In the heart of Europe, the Peace Committee sat in the heart of a contradiction, for there were few places less peaceful than the Balkans. Yet Slovene PEN members played an important role as did other PEN members in bridging divides among writers in conflict zones.

At the Peace Committee’s inception in 1984, Slovenia was part of Yugoslavia, one of a handful of Communist countries after World War II whose writers were able to sign PEN’s Charter which endorsed freedom of expression. The other countries included Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Hungary. In 1962 a well-known Slovene writer, who was a member of English PEN but returned each year to Slovenia, championed the idea of resurrecting the Slovene PEN center which had existed before the war as well as the other two Balkan PEN Centers—Croatia and Serbia.

In 1965 writers from these Yugoslav centers took on the task of staging an International PEN Congress in Bled. At the congress Arthur Miller presided as the first and only American President of International PEN. At the ’65 Bled Congress PEN also hosted for the first time Soviet writers as observers. “Almost despite myself I began feeling certain enthusiasm for the idea of international solidarity among writers, feeble as its present expression seemed,” Miller wrote in his autobiography Timebends. “…I knew that PEN could be far more than a mere gesture of goodwill.”

It took almost 25 years before a Soviet, and later Russian, PEN Center emerged. [see PEN Journey 3, 6, 8] During the Cold War it was difficult for writers from the East and West to communicate, but at PEN congresses and meetings and at the Peace Committee, writers debated, exchanged ideas and shared literature. The Peace Committee became a haven during the Balkans War and also a meeting ground for writers from other conflict areas.

Unlike the Writers in Prison Committee which worked to protect and liberate individual writers, it was difficult at times to define the concrete actions the Peace Committee could take, but at least three stand out in my memory—one direct action, one initiative and one rigorous debate on a pressing issue.

As noted in an earlier post [PEN Journey 7] the head of Slovene PEN, Boris Novak ran the barricades during the Balkans War with aid for writers in the besieged Sarajevo as did Slovene poet and future Peace Committee Chair Veno Taufer and others. At the Peace Committee meeting in 1994 Boris reported 100,000 DEM ($60,000) had been contributed from PEN centers around the world and delivered to almost 100 Bosnian writers in order to save lives. When a new Bosnian center was elected at PEN’s Congress in late 1993, the Bosnian center began taking over the delivery of aid, and Boris was elected chair of the Peace Committee.

Boris Novak. Photo credit: The Bridge Magazine Veno Taufer. Photo Credit: Alchetron

I attended my first Peace Committee Conference as Chair of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee in 1994 at the midway point of the Sarajevo siege. At the time PEN was also being asked to help writers who managed to get out of the city. In London I’d met one of these Bosnian writers and gave him my son’s old computer which he accepted as if I’d given him the keys to the city for he had no means to write. Writers fleeing not only the Balkans but situations in Africa and the Middle East needed support as they landed in new locations. It was at the Peace Committee meeting in 1994 that PEN’s Exile and Refugee Network was first conceived in partnership with the Writers in Prison Committee. The initiative was confirmed at the PEN Congress later that fall in Prague.

This initiative for exiles and refugees moved into an exploratory phase which became a leit motif in PEN’s work over the next two decades as it had been in the decades past. PEN’s Exile Network, spearheaded by PEN Centers, including Canada, Sweden, Norway, Germany, Belgium, England, America and many others took the initiative and offered residencies, aid and services to refugee and exiled writers arriving in their countries. Eventually PEN International formed a partnership with the expiring Parliament of Writers Cities of Asylum. In 2006 PEN became a founding member of ICORN—International Cities of Refuge Network. [More in future blog post]

The following year in 1995 the Peace Committee meeting in Bled featured a debate on hate speech, seen as both cause and effect in the conflicts. The gathering included such intellectual luminaries as Adam Michnik, an architect of Poland’s Solidarity movement and editor of the leading newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza in Warsaw. The debate was lively over the incendiary nature of hate speech and the limitations that should be imposed. Both in the Balkans War and in the civil war in Rwanda, which had just ended the year before, hate speech and writing fueled the strife. In spite of PEN’s advocacy for free expression, PEN also called on its members “to use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people” and pledge “to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds.” Even as “PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship,” it recognizes “freedom implies voluntary restraint” and members pledge “to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

The very Charter of PEN contained the axis of the debate. What were or should be limits on expression? Should PEN take a position? At the 1995 Peace Committee conference and in debates since, the views tended to fall according to cultural and national experience. Those in Europe, Africa and elsewhere who had experienced effects of hate speech urged stricter limitations on speech; whereas Americans, bred on the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, remained wary of limits and argued that the answer to offensive speech was more speech, the drowning out of harmful ideas with inspiring ones. In my notes of the meeting and debate that year, I find no consensus or clear recommendation except for a reminder from one speaker who knew and quoted Russian exile and dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: “Don’t go against your conscience and don’t tell lies!”

Proposal at 61st Congress for PEN to explore setting up an Exile Network. Resolution passed.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 15: Speaking Out: Life and Death