Posts Tagged ‘American PEN’

PEN Journey 17: Gathering in Helsingør

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

What I remember most about the gathering of colleagues from 28 countries—31 PEN centers—51 of us in all at the first Writers in Prison Committee conference in 1996 was the seriousness of purpose and intellect during the day and the fun and talent in the evenings.

Hosted by Danish PEN, writers from every continent gathered at a university in Helsingør—known in English as Elsinore, the home of Shakespeare’s Hamlet—where we met in workshops and ensemble during the day to shape and refine our work on behalf of writers and freedom of expression around the world. But in the evening we were at a small university in a small city without transportation or distraction so we entertained ourselves. Each delegate displayed talents—from poetry reading to song to dance to musical performances.

As Chair of the WiPC gathering, I’d brought none of my own writing to read and was left to exhibit meager other talent which consisted of playing a few opening bars of Für Elise on the piano and whistling tunes with my far more talented Danish and Russian colleagues. Archana Singh Karki from Nepal in flowing red dress entertained with her graceful dance; Siobhan Dowd, our Irish former WiPC director and Freedom of Expression director at American PEN, silenced us with her soulful Irish folk songs, sung acapella; Sascha, Russian PEN’s General Secretary, not only whistled robustly but recited his poetry, which I was told I should be glad I didn’t understand with its bawdy content; Sam Mbure from Kenya and Turkish/English novelist Moris Farhi also read and recited work. PEN International President Ronald Harwood joined the discussions in the day and was audience in the evening. I don’t recall if Ronnie offered his own work, but we all bonded in our mission and in our support for the talent in the room.

Entertainment in the evening: From the top left—Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Chair of WiPC)in a whistling song; Rajvinder Singh (German PEN, East) accompanying Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN) in dance; Siobhan Dowd (at piano—English & American PEN) with Moris Farhi (reading—English PEN); Sam Mbure (reciting—Kenyan PEN); Niels Barfoed (reading—Danish PEN)

During the three days, we fine-tuned our methods of working on and campaigning for our main cases, those writers who were imprisoned, attacked or threatened because of their writing, often their nonviolent voice of protest against authoritarian regimes. We considered PEN’s decision-making on borderline cases such as those which included drug charges, advocacy of violence, pornography, hate speech, terrorism. These were not categories we normally took on as cases. We discussed when we might take up such a case or assign them to investigation or judicial concern. We laid the groundwork for more joint actions among centers and other organizations such as the U.N., OSCE and IFEX, the International Freedom of Expression Exchange.

Round Table of the WiPC conference which included delegates from PEN centers in Switzerland, Jerusalem, Denmark, England, Mexico, Portugal, America, Norway, Czech Republic, Ghana, Canada, Australia (Melbourne and Sydney), Portugal, Finland, Nepal, Scotland, Malawi, Kenya, Ghana, Croatia, Slovakia, Sweden, Spain, Austria, Japan, Germany, Russia, Poland, Netherlands

With PEN’s WiPC staff Sara Whyatt and Mandy Garner, we set out a campaign calendar for the year, beginning with Turkey in May; China in June; Myanmar in July; Guatemala in September; Vietnam in October; Nigeria in November; Human Rights Day focus in December; Cuba in January; Rushdie and Fatwa and Iran in February; United Nations Commission on Human Rights lobbying in February/March and a return to China during the Chinese New Year in February/March; International Women’s Day in March and World Press Freedom Day in May. This campaign calendar meant that the London office would send information each month related to these foci, and PEN centers would plan programs if the campaign fit their work and the cases they had taken on.

We discussed the elements of successful missions to troubled areas and what future missions should be considered. In 1997 PEN International and Danish PEN sent representatives on a quiet mission to Cuba. We also strategized on the effect of writers observing trials in certain countries, particularly in Turkey.

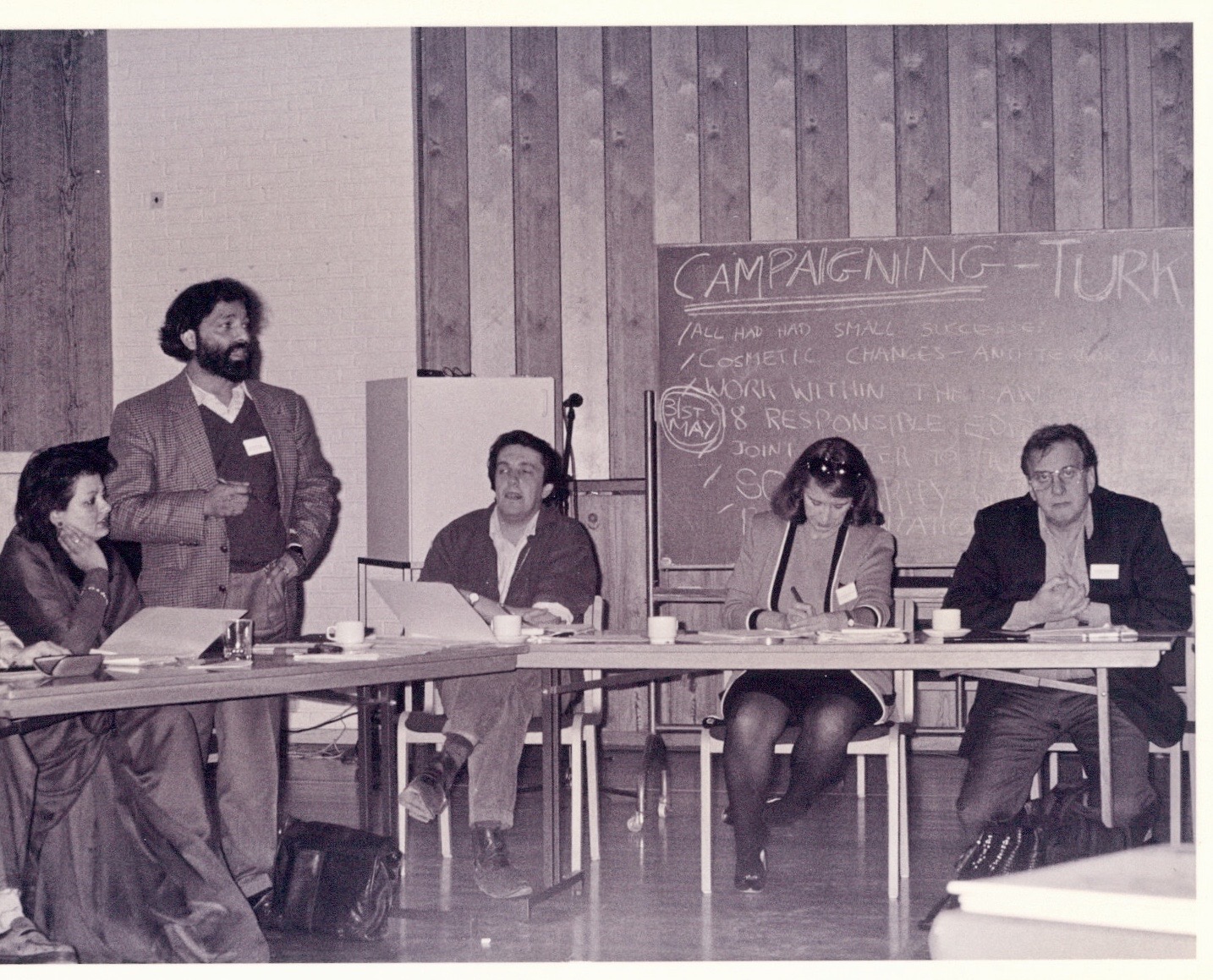

Working session on Turkey Campaign at at WiPC conference: L to R: Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN), Rajvinder Singh (German PEN, East), Robin Jones (WIPC staff), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (WiPC Chair), Ronald Harwood (PEN International President)

During the conference a request came for members of PEN to sign on individually and en mass as publishers of a book in Turkey which republished an article by the famed Turkish novelist Yaşar Kemal, along with articles by other Turkish writers who were in prison because of their writing. Kemal had recently been charged because of an article he’d published in the German magazine Der Spiegel about the Kurds. The organizer in Turkey had gathered hundreds of Turkish writers, publishers, artists, and actors to sign on as publishers. They wanted to present the book and the list of hundreds of publishers to challenge the courts to bring charges against everyone. Many of us agreed to participate. This act launched a campaign in Turkey and a mission later in 1997. (Blog to come.) The independent Turkish Freedom of Expression Initiative has since gathered biennially for the last 23 years. For this kind of joint action PEN was primed to cooperate.

Finally in Helsingør the Writers in Prison Committee took a step towards opening up the election process for the WiPC Chair. My term was due to expire at the fall 1996 Congress in Guadalajara. We decided to select a nominating committee from members to find candidate(s) for the next chair rather than have the post appointed by the Secretariat in London. That process was later replicated in other elections in PEN and is standard procedure today.

Workshop: From left includes: Neils Barfoed (Danish PEN), Lady Diamond (Ghana PEN), Moris Farhi (English PEN), Sara Whyatt (WiPC Programme Director), Mandy Garner (WiPC researcher), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (WiPC Chair at front)

Helsingør was a fitting venue for the first WiPC Conference, not only because of its literary credentials with the Kronborg Castle where most of Shakespeare’s Hamlet takes place, but also because of its historic legacy in World War II. Helsingør was one of the most important transport points for the rescue of Denmark’s Jews. A few days before Hitler had ordered that the Danish Jews were to be arrested and deported to concentration camps October 2, 1943, one of the Nazi diplomatic attaches who’d received word in advance shared the information with the Jewish community leaders. Using the name Elsinore Sewing Club, the Jewish leaders communicated with the population, and the Danes moved the Jews away from Copenhagen to Helsingør, just two miles across the straights to neutral Sweden. The Danish citizens hid their fellow Jewish citizens until they could get onto fishing boats, pleasure boats and ferry boats and escape over a period of three nights. The Danes managed to smuggle the majority of its Jewish citizens—over 7200 Jews and 680 non-Jews—across the water to safety.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 18: Picasso Club and Other Transitions in Guadalajara

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.

In those days PEN had close ties with UNESCO, and attending a PEN Congress was like visiting a mini U.N. Assembly. Delegates sat at tables with name tags of their countries in front of them. Action was taken by resolutions which were debated and discussed and then sent to the International Secretariat and back to the Centers for implementation. At the time PEN operated with three standing Committees, the largest of which was the Writers in Prison Committee focused on human rights and freedom of expression. The other two were the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and the Peace Committee. Soon, in 1991, a fourth—the Women’s Committee—would be added. At parallel and separate sessions to the business of the Assembly of Delegates, literary sessions explored the theme of the Congress.

PEN USA West was particularly active in the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) where we advocated for our “adopted/honorary” members, most prominent for us at that moment was Wei Jingsheng in China. We had drafted and brought to the Congress a resolution, noting that China had recently released numbers of individuals imprisoned during the Democracy Movement, but Wei Jingsheng had not been among them and had not been heard from. We addressed an appeal to the People’s Republic of China to give information on the condition and whereabouts of Wei Jingsheng and to release him.

Before we spoke to this resolution on the floor of the Assembly, we met with the delegate of the China Center. The origins of this center was a bit of a mystery since it was one of the few centers that defended its government’s actions rather than PEN’s principles. I still recall the delegate with thick black hair, square face, stern visage and black horn-rimmed glasses, though this last detail may be an embellishment. He argued with me that Wei Jingsheng was an electrician, not a writer, that he had simply written graffiti on a wall, but that he had committed a crime by sharing “secrets” with western press.

The Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee Thomas von Vegesack, a Swedish publisher, arranged for the celebrated Chinese poet Bei Dao, a guest of the Congress, to speak in support of the PEN USA West resolution. The delegate from Taipei PEN stood next to Bei Dao and translated his words which contradicted the China delegate. Bei Dao noted that Wei Jingsheng had been in prison ten years already, having been arrested when he was 28-years-old. He had already published his autobiography and 20 articles and for years had been editor of the magazine SEARCH. In his posting on the Democracy Wall and in his essay “The Fifth Modernization,” Wei had suggested that democracy should be added as a fifth modernization to Deng Xiaoping’s four modernizations. “This shows that Wei Jingsheng’s status as a writer can’t be questioned,” Bei Dao said. I still remember that moment of Bei Dao addressing the Assembly and his country man with a Taiwanese writer translating. For me it demonstrated PEN in action.

In Beijing at that time thousands of students and citizens were protesting in Tiananmen Square.

PEN Center USA West’s resolution passed. The China Center and Shanghai Chinese Center refused to accept the resolution. The Maastricht Congress was the last PEN Congress they attended for over twenty years.

In the months preceding the gathering in Maastricht International PEN Secretary Alexander Blokh, International President Francis King and WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack had visited Moscow where the groundwork was laid to bring Russian writers into PEN with a Center independent of the Soviet Writers Union.

Twenty-two years before, Arthur Miller, International PEN President, had also traveled to Moscow at the invitation of Soviet writers who wanted to start a PEN center.

In 1967 Miller met with the head of the Writers’ Union and recounted in his autobiography:

At last Surkov said flatly, “Soviet writers want to join PEN….”

“I couldn’t be happier,” I said. “We would welcome you in PEN.”

“We have one problem,” Surkov said, “but it can be resolved easily.”

“What is the problem?”

“The PEN Constitution…”

The PEN Constitution and the PEN Charter obliged members to commit to the principles of freedom of expression and to oppose censorship at home and abroad. Miller concluded that the principles of PEN and those of the Soviet writers were too far apart. For the next twenty years PEN instead defended and assisted dissident Soviet writers.

At the Maastricht Congress Russian writers, including Andrei Bitov and Anatoly Rybakov attended as observers in order to propose a Russian PEN Center. Rybakov (author of Children of the Arbat) told the Assembly that writers had “endured half a century of non-democratic government and had lived in a dehumanized and single-minded state.” He said, “Literature could be influential in the fight against bureaucracy and the promotion of the understanding between nations and cultures. Now Russian writers want to join PEN, the principles and ideals of which they fully shared, and the responsibilities of belonging to which they recognized…and hoped for the sympathy of the members of PEN.”

The delegates unanimously elected Russian PEN to join the Assembly. In the 1990’s and until he passed away in 2007, one of the most outspoken advocates for free expression in Russia was poet and General Secretary of Russian PEN, Alexander Tkachenko. (Working with Sascha, as he was called, will be included in future blog posts.)

Polish PEN was also reinstated at the Maastricht Congress. After seven years of “severe restrictions and false accusations by the Government which had resulted in their becoming dormant,” the Polish delegate said they were finally able to resume normal activity in full harmony with PEN’s Charter. “I must stress here that our victory we owe in great part to the firm and unbending attitude of International P.E.N. and to almost unanimous solidarity of the delegates from countries all over the world.”

At the Congress PEN USA West, American PEN, Canadian PEN and Polish PEN presented a resolution on Czechoslovakia, calling for the government to cease the recent campaign against writers and to release Vaclav Havel and all writers imprisoned. The Assembly recommended that the International PEN President and International Secretary get permission from Czech authorities to visit Vaclav Havel in prison. Two weeks after the Congress Vaclav Havel was released. In December of 1989 Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia after the collapse of the communist regime. In 1994, President Havel, along with other freed dissident writers, greeted PEN members at the 61st PEN Congress in Prague.

Also at the Maastricht Congress was an election for the new President of International PEN. Noted Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe stood as a candidate, supported by our two American Centers, Scandinavian centers, PEN Canada, English PEN and others, but Achebe was relatively new to PEN, and at the time there were only a limited number of African centers. Achebe lost by a few votes to the French writer Rene Tavernier, who passed away six months later.

Achebe admitted that he was not as familiar with PEN but said that if the organization had wanted him as President he had been persuaded that “it would be exciting.” He noted the world was very large and very complex. He hoped that in the years to come the voices of those other people would be heard more and more in PEN.

Our delegation had the pleasure of having dinner with Achebe in a castle in Maastricht which had a gourmet restaurant that served multiple courses with tiny portions. The small dinner, which also included the East German delegate and I think fellow Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta and an American PEN member, lasted over three hours. I’m told when Achebe left, he asked his cab driver if he had any bread in his house because he was still hungry. When I saw Achebe a few times in the years following, he always remembered that dinner.

At the Maastricht Congress two new Africa Centers were elected: Nigeria, represented by Achebe, and Guinea. The election of these centers signaled a growing presence of PEN in Africa. Today PEN has 27 African centers.

A few weeks after we returned from the Congress to Los Angeles, tanks entered Tiananmen Square. Hundreds of citizens, including writers, were arrested and killed. One of my first thoughts was, what will happen to Bei Dao, but fortunately he hadn’t yet returned to China. Our small PEN office started receiving faxes from London with dozens of names in Chinese, and we and PEN Centers around the globe began writing and translating those names and mounting a global protest. Among those on the lists I am sure, though I didn’t know him at the time, was Liu Xiaobo, who was instrumental in helping protect the students and in clearing the square.

Tiananmen Square. June 4th, 1989. © 1989 Stuart Franklin/MAGNUM

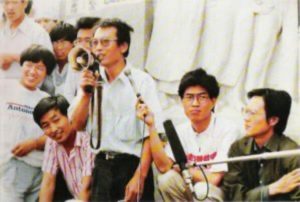

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Twenty years later Liu Xiaobo would be a founding member and President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He would also later help draft and circulate the document Charter 08, patterned after the Czechoslovak writers’ document Charter 77, calling for democratic change in China. In 2009 Liu Xiaobo was again arrested and imprisoned. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in prison in 2017.

The opening of the world to democracy and freedom which we glimpsed and hoped for and which seemed imminent in 1989 appears less certain now.

Today, June 3-4, 2019 memorializes the thirtieth anniversary of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square. During the years after Tiananmen when Liu Xiaobo and others were in prison I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. But that is a story to come…

Next Installment: PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East