Foxes and Hedgehogs

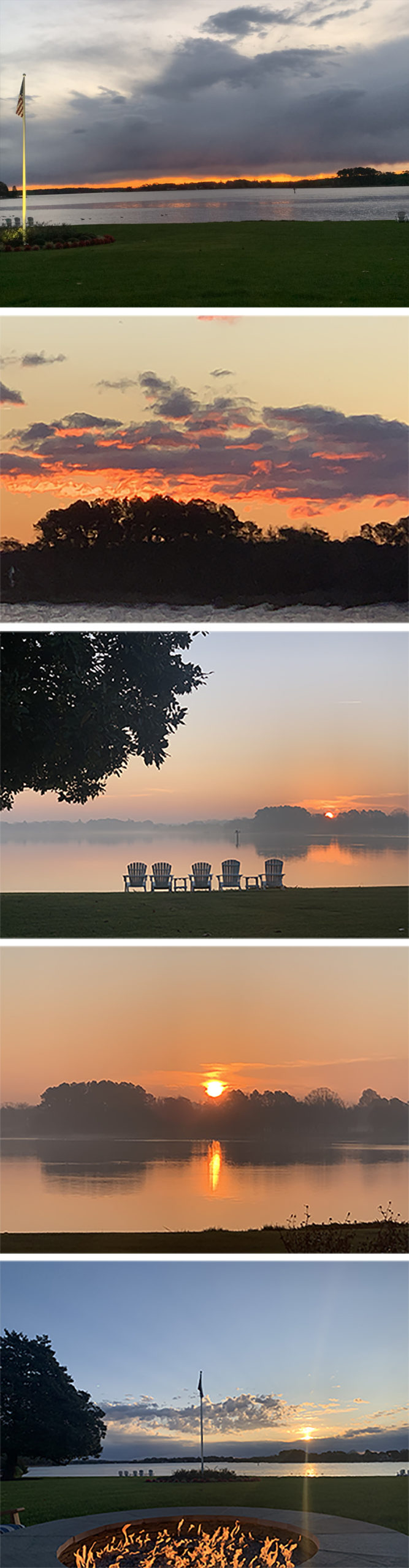

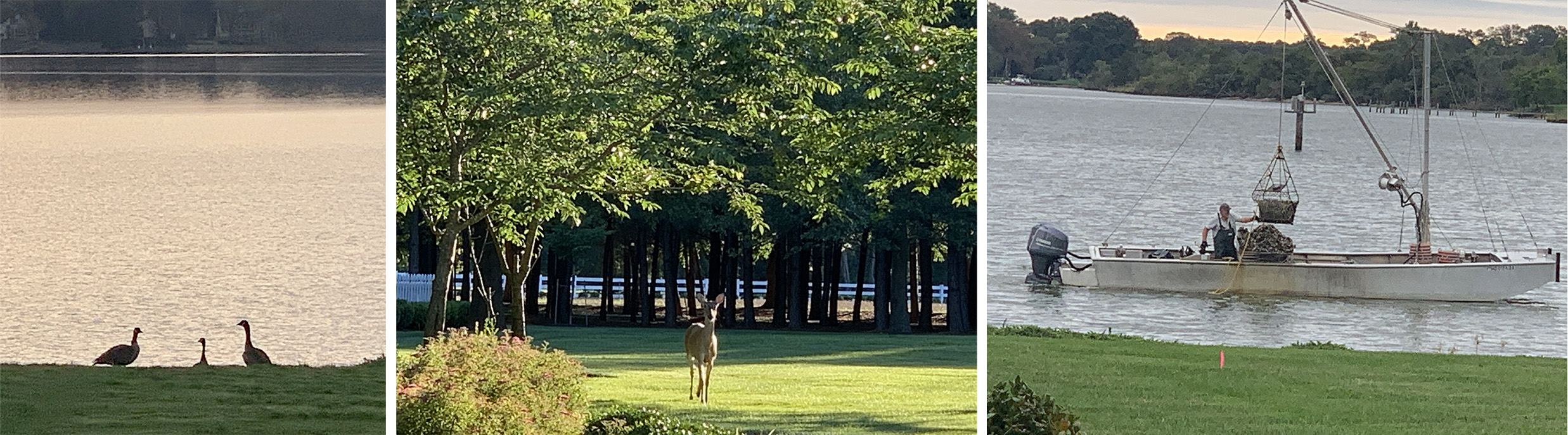

I’ve looked out on the same scene every morning for the past 20 months—a quiet river, brownish blue depending on the light, a spreading magnolia tree, large deciduous trees on the near shore, a flagpole, Adirondack chairs by the water, and the sun creeping over the horizon. The sun’s entrance shifts between the trees on the far shore depending on the season.

Each morning I slip outside as the dark sky grows light and sit by the firepit where I think and write and take pictures. I can’t stop taking pictures even though it is of the same scene. Each morning I see slight changes in the clouds, or in the way light hits the water, or in the way the ducks line up to swim. I take pleasure in these variances. Because I’m viewing the world now largely from one place, I’m able to see the subtle nuances of beauty and affirm the continual creative movement of life.

Before the pandemic, I was frequently on the road, either researching for books or for work with organizations relating to human rights, education, and conflict, or for a combination of these. I was a fox skirting from place to place, not a hedgehog burrowing in. Isaiah Berlin’s essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” published in 1953, classified people as foxes who know many things or as hedgehogs who know one big thing. I have lived more as a fox, certainly as a journalist, going out and covering a variety of issues and as a writer in general. I’ve had the privilege of traveling and writing and working across the globe. But recently, at least in terms of locations, I am becoming a happy hedgehog, knowing my one spot.

Children begin with one view, one place and slowly take in the larger world which they enter as they grow and learn, but then often return to one place at a later stage in life. Such was the riddle of the Sphinx in Greek mythology to keep intruders out of Thebes. The Sphinx posed the riddle to anyone who wanted to enter. If the visitor answered correctly, he could gain entrance, but none except Oedipus knew, and when the others faltered, the Sphinx ate them.

What goes on four feet in the morning, two feet at noon, and three feet in the evening? Answer: a person: A person as a baby in the morning of their life crawls on four feet (hands and knees).

As an adult in the noon of their life, they walk on two feet. But when they are old, in the evening of their life, they walk with a cane, on three feet.

I remain on two feet and hope still to get to Thebes, but I have learned in this pandemic time, the pleasure of stillness and of one place.

As in the past, I’ve aggregated here posts of a single month as a way of slicing time since 2008—before the flood. The posts range geographically and peer out of a large window on the world from China, Belarus, Iraq, Jordan, Greece, Turkey, England and the United States. Many posts focus on the theme of free expression and on those who have been on the front lines. In spite of the struggles, or maybe because of them, the posts end with the observation: “I Have a Better Feeling About Tomorrow.”

Photos by Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

December 30, 2008: Charter 08: Decade of the Citizen

Grandstands are rising around Washington, DC. The U.S. is preparing for the Inauguration of a new President whose campaign mobilized a record number of citizens and focused on themes of hope and change.

Halfway around the globe in the world’s most populous country, a relatively small group of citizens are proposing radical change for their nation, change which reflects in large part the ideals upon which the United States was founded. However, the proponents of this change have been interrogated and arrested.

On December 10, the 60th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 300 leading mainland Chinese citizens—writers, economists, political scientists, retired party officials, former newspaper editors, members of the legal profession and human rights defenders–issued Charter 08. Charter 08 sets out a vision for a democratic China based on the citizen not the party, with a government founded on human rights, democracy, and rule of law. Charter 08 doesn’t offer reform of the current political system so much as an end to features like one-party rule. Since its release, more than 5000 citizens across China have added their names to Charter 08.

Before the document was even published, the Chinese authorities detained two of the leading authors Liu Xiaobo and Zhang Zuhua and have since interrogated dozens of others who signed. Most have been released though they continue to be watched. However, Liu Xiaobo, a major writer and former president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, remains in custody with no word of his whereabouts and fears that he will be charged with “serious crimes against the basic principles of the Republic.” The Chinese government has also blocked or deleted websites and blogs that carry Charter 08.

Charter 08 was inspired by a similar action during the height of the Soviet Union when writers and intellectuals in Czechoslovakia issued Charter 77 in January, 1977. Charter 77 called for protection of basic civil and political rights by the state. Among the signatories was Vaclav Havel, who was imprisoned for his involvement but went on to become the President of the Czech Republic after the Soviet Union ended.

Citizens around the globe, including Vaclav Havel, Nobel laureates, human rights defenders, writers, economists, lawyers, academics, have rallied in support of those who signed Charter 08. The European Union has expressed grave concern at the arrest of Liu Xiaobo and others. Petitions in support of Charter 08 and in protest over the detention of Liu Xiaobo are circulating around the world.

The arrest of Liu Xiaobo happened on the eve of Human Rights Day and the 60th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The year 2008 is also the 110th Anniversary of China’s Wuxu Political Reform, the 100th Anniversary of China’s first Constitution and the 10th Anniversary of China’s signing of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the soon-to-be 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown against students….[cont]

December 22, 2009: Hard Edge Under the Snow

Washington, DC is emerging from its winter wonderland of nearly two feet of light powdery snow over the weekend. With snow crested on rooftops and banked along the streets, with sparkling lights blinking around town, circling the monuments and the White House, the city looks like a postcard for the holidays.

Over the weekend if you didn’t have to travel, the record snowfall—between 15-20 inches, the largest ever in December—was magical. We walked into a restaurant with a fireplace, met with family and friends for lunch then played in the park with our family dogs—one old dog and two puppies—who jumped and romped and tumbled through the snow as if it had fallen for their pleasure, theirs and the children who were sledding down the hill.

But the snow has now begun to melt during the day and to freeze at night, leaving crusty, icy mounds. From the window it is still beautiful, but it is a pain if you are trying to park a car at the curb or walk along paths not dug out when it was fluffy. The holiday lights still blink, and the puppies still race across the white fields as if life was all that it was meant to be.

And yet as I sit here typing this December blog, trying to settle into the holiday spirit, I am acutely aware that half a world away a trial is under way at this very moment in Beijing for a Chinese writer and dissident whose “crime” was to draft, along with other Chinese citizens, a vision–Charter 08–calling for human rights, rule of law and democratic reform in China.

An important writer and literary critic, Liu Xiaobo was held for six months at a secret location, then formally arrested and transferred to a detention center in June, and finally twelve days ago indicted for “incitement to subvert state power.” He is being brought to trial today– December 23–less than two weeks after the indictment and on the eve of Christmas when many diplomats and journalists will be away. His motion to postpone so his defense could have time to read and prepare against the 20 volume indictment was denied. Liu’s wife was told she can’t observe the trial and has instead been named a prosecution witness. Across China activists and supporters of Liu’s have been warned to stay home and not participate in any activities in support of Liu. These actions have led China observers to conclude that the trial is purely political and a guilty verdict has already been determined.

Around the world freedom of expression and human rights organizations and activists are preparing for the worst—a long jail sentence for Liu. A vigil has been called at the Chinese embassy in New York. Petitions are being prepared and at the same time lobbying continues in the hope for some recourse.

At this holiday season when hope is celebrated and rebirth, anticipated, the voice of a single Chinese citizen echoes as light as snow falling on grass and as hard as the frozen earth beneath.

December 22, 2010: In the Woods: On History’s Doorstep

In the woods outside Minsk, Belarus an Olympic training center sprawls among the snow-capped pine trees. Here athletes, including wrestlers from all over Europe, particularly the former Soviet Union, come to train. These young men—mostly they are men though occasionally women wrestlers train there—exercise, practice and then “go live” several times a day. From this center Olympic medalists emerge. Politics can seem as remote as the camp itself.

This past weekend in Minsk, approximately 20 miles away, as many as 10,000 people protested the outcome of Belarus’ presidential elections. Incumbent Alexander Lukashenko, in power since 1994, won the election in a process widely criticized by both official outside observers (the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe OSCE) and opposition parties. More than 600 people, including journalists, human rights activists and most of the opposition presidential candidates, were attacked and arrested. Among those arrested was Vladimir Neklyaev, writer and former president of Belarusian PEN, who was severely beaten, hospitalized and then taken away from the hospital to an unknown location, since identified as the Belarus State Security Agency (KGB).

Belarus, which is bounded by Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Ukraine and Russia, is itself wrestling between the ideologies and political systems of open democracy and authoritarian rule. Belarus has been called Europe’s last dictatorship.

As a new decade arrives and the twentieth anniversary of the breakup of the Soviet Union is observed, Belarus may be one of the telltales to judge the direction history leans. One hopes it will arrive at fair and open competition. In the Olympics it would certainly be grounds for disqualification if an athlete at any point before or after the competition attacked his or her fellow athletes.

December 17, 2011: Across the Divide

On the eve of Christmas in December 1914 and 1915 in the middle of World War I British and German forces faced each other in the trenches across battle lines and called a temporary truce. On fields in France and Belgium, the troops climbed out of their trenches and played games of football in No Man’s Land. They also retrieved their dead and repaired their trenches. In one location a joint service was held with British and Germans officiating. The soldiers then climbed back into their fox holes and continued the battle.

One Royal Welch Fusilier recounts: “At 8:30 I fired three shots in the air and put up a flag with ‘Merry Christmas’ on it, and I climbed on the parapet. He put up a sheet with ‘Thank You’ on it and the German captain appeared on the parapet. We bowed and saluted and got down into our respective trenches, and he fired two shots in the air, and the War was on again.”

At this holiday season may we each find ways to reach across the divides in our lives and in our nations. May insurmountable differences become surmountable and irreconcilable opinions find a path. May divisions and hatreds be leavened with the spirit of universal love and may truce turn into peace.

Happy holidays!

December 2012: No blog posted

December 5, 2013: Welcome Home? Syrian Refugees Building On Top of History

(A version of this article was published on GlobalPost.)

I recently returned from visiting Syrian refugees in northern Iraq and Jordan on a field mission with Refugees International. As I handed over my passport and custom’s form to the U.S. officer, he said: “Welcome home!”

That greeting always touches me but more than ever after this trip spending time with refugees who have no idea when and if they might be able to go home, who no longer know where their home is. Hundreds of thousands are living in tents and caravans and many in even more problematic structures in fields and behind houses across the border from Syria. Men, women and children–often on foot or in buses and taxis–have fled into Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey and countries further away.

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

The displacement from the three-year-old civil war in Syria has caused the worst refugee crisis since Rwanda, according to officials at the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR). They estimate that at least two million people have fled across Syria’s borders and millions more are internally displaced. Adding to the challenge of assisting these people are the growing restrictions on crossing from Syria into Iraq and Jordan, restrictions which some complain are tantamount to closing the borders.

In Jordan, a country of six million people, the UNHCR believes that there are nearing 600,000 refugees, and some others estimate the figure to be over a million. In both Iraq and Jordan, only a third of the refugees are in camps; the rest are dispersed throughout cities and towns, often unregistered and without services.

“We walked three days in the dark, at night, afraid, carrying our two children,” said one young man, who travelled with his wife and three-year-old son and one-year-old daughter, trying to avoid the fighting. They finally got a ride and arrived at Za’atari refugee camp in the desert of northern Jordan. The Za’atari camp, originally built for 10,000 people, currently houses over 80,000 and at times has held as many as 150,000. The camp is now the fourth largest “city” in Jordan.

Though conditions have improved considerably, according to those who have visited the camp in the past, the landscape at Za’atari is stark—five square miles of barren rocky desert with tents and caravans laid out as far as the eye can see. There is not a single tree or bush or plant anywhere, nothing to break the view except coiled barbed wire around certain parts of the compounds. Running through the middle of the acres of desert is a dusty path with stalls on either side where residents sell vegetables, clothes, shoes and other wares. The residents have dubbed it the Champs Élysées. A new camp nearby has been set up and will soon take the overflow from Za’atari.

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

The conflict in Syria is only eight miles away. According to one humanitarian aid worker, you can sometimes hear the explosions. The proximity to the border and the conflict adds to the insecurity in the camp.

“Za’atari is the tip of the iceberg of the Syrian crisis,” said Kilian Kleinschmidt, the camp manager….[cont]

December 2014: No blog posted

December 31, 2015: Refugees: The Great Walk Now or Never

The black rubber dinghy had just landed on Mytileni’s rocky beach on the Isle of Lesvos, Greece. The 41 people crammed precariously on the raft quickly dropped their orange life jackets and looked around to make sure their friends and relatives had also made it to land.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

A father knelt before his curly headed son, around 3 years old, took off his life jacket, checked his clothing—damp, but not too wet—and tried to explain where they were. The boy smiled, looked about and then spent his time trying to get his heel back into one of his wet sneakers. I was able to help him as his father looked for his wife, who’d made it to land further down the beach. The family had left Aleppo a week ago, waited three days on the Turkish coast near Izmir for transport and now, finally had safely reached the shores of Europe.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

From here they would continue their long journey to a new life, which they hoped would be in Germany. Before them lay at least half a dozen train and bus rides and walks with their two backpacks containing all their belongings. Also ahead were multiple registration centers in each country they would pass through.

Along with the 760,000 people who have come through Greece since April, they were embarking on “The Great Walk,” or some call the trek “The Great Wait.” With winter coming and borders closing, it is a “now-or-never” journey as Europe absorbs the largest migration since World War II. Almost half—45%—come through Lesvos, 58% men, 16% women, 26% children, according to statistics from the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR).

As Syrians, they are lucky, if having to flee one’s home destroyed in war can be considered luck. Most Syrian refugees—96-98%—will eventually find new residencies. Syrians comprise 45% of this great exodus. Another third are Afghan, a tenth are Iraqi. The rest are Eritrean, Central African Republic, Iranian, Somalians, Moroccan, Algerians and others, according to figures from UNHCR. The latter four nationalities have slim chances to resettle in Europe.

In the past month access for “direct arrivals” has closed. Only refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan are allowed the onward journey into Europe. These nationalities comprise 85% of those on the move. The rest are turned back. The European Union has also agreed to accept 160,000 in a formal resettlement process, which takes one to two months and requires refugees to accept whatever country they are assigned. Again, only certain nationalities are included in this relocation process—Syrians, Iraqis, Eritreans, those from the Central African Republic and perhaps soon Afghans, according to Alessandra Morelli, UNHCR Senior Operations Coordinator in Greece.

“History is passing in front of our eyes,” Ms. Morelli says at the UNHCR office in Athens. “I feel responsible that we build a Europe that is open and not one of walls….[cont]”

December 27, 2016: Hope for Songs Not Prison in 2017

The last time I saw Şanar Yurdatapan we had coffee in the press building in Istanbul after Human Rights Watch released its 2016 World Report “Politics of Fear and the Crushing of Civil Society”. I’ve known Şanar for almost 20 years, ever since I headed PEN International’s delegation for his first Initiative for Free Expression in Istanbul in 1997.

A noted and popular musician and song writer, Şanar has dedicated the last decades to defending and trying to open up space in Turkey for free expression. He’s done so by monitoring, reporting and organizing on behalf of writers and artists under threat. At our coffee a year ago he told me he was retiring, or at least going back to song writing and handing over the mantle of leadership to the younger generation.

However, in the past year freedom of expression has been under siege in Turkey with 150-170 writers and journalists now in prison and hundreds of news organizations closed down. This past week Şanar was called before prosecutors for his advocacy on behalf of the closed newspaper Özgür Gündem, (Turkish for “Free Agenda”), the chief newspaper read by Kurds.

“It is both the duty and the right of a journalist to report; his is freedom of information at the same time and right to freedom and right of all of us,” Şanar is reported to have told the court.

At the end of the hearing the prosecutor demanded that Şanar be imprisoned for over ten years for “propaganda for the organization” under the Anti-Terror Law. The hearing is January 13, 2017. Şanar is now 75.

Since the failed coup in July the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has increased the detainment and arrest of writers, journalists and academics for their peaceful opposition to his policies. These have included noted novelist Asli Erdoğan and leading linguist Necmiye Alpay, who spent her 70th birthday in detention. Brothers Ahmet Altan, a novelist, and Mehmet Altan, an academic, are held in maximum security Silivri prison facing terror charges, unable to receive books, letters or any communication from outside or to visit the prison library.

As the year 2016 ends with an increase of terror attacks around the world, with a new administration about to take power in the U.S., with existing administrations struggling to hold onto power in Europe, with a collapsing Syria and a continual tide of refugees around the world, with an odd dance between super powers and aspiring super powers, the single citizen voice can get overlooked. But history has shown that when the individual voice, especially those of writers who dissent, gets stifled, the arc of history is bending towards conflict and away from peace which leaders and citizens say they want.

In the new year PEN International hopes to go to Turkey to add support firsthand for Turkish writers and for the important role they play right now in keeping that arc from bending too far backwards. We will watch and argue for the fate of Şanar and others and hope that he will be writing songs in the years ahead, and not from prison.

December 7, 2017: Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo died this past July in prison, where he was serving an 11-year sentence for his role in drafting Charter ’08 calling for democratic reform in China. Below is my essay in The Memorial Collection for Dr. Liu Xiaobo, just published by the Institute for China’s Democratic Transition and Democratic China.

I never met Liu Xiaobo, but his words and life touch and inspire me. His ideas live beyond his physical body though I am among the many who wish he survived to help develop and lead democratic reform in China, a nation and people he was devoted to.

Liu’s Final Statement: I Have No Enemies delivered December 23, 2009 to the judge sentencing him stands beside important texts which inspire and help frame society as Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail did in my country. King addressed fellow clergymen and also his prosecutors, judges and the citizens of America in its struggle to realize a more perfect democracy.

I hesitate to project too much onto Liu Xiaobo, this man I never met, but as a writer and an activist through PEN on behalf of writers whose words set the powers of state against them, I can offer my own context and measurement.

Liu said June 1989 was a turning point in his life as he returned to China to join the protests of the democracy movement. In June 1989 I was President of PEN Center USA West. It was a tumultuous year in which the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was issued in February, and PEN, including our center, mobilized worldwide in protest.

In May 1989 I was a delegate to the PEN Congress in Maastricht, Netherlands where PEN Center USA West presented to the Assembly of Delegates a resolution on behalf of imprisoned writers in China, including Wei Jingsheng, and called on the Chinese government to release them. The Chinese delegation, which represented the government’s perspective more than PEN’s, argued against the resolution. Poet Bei Dao, who was a guest of the Congress, stood and defended our resolution with Taipei PEN translating.

When the events of Tiananmen Square erupted a few weeks later, my first concern was whether Bei Dao was safe. It turns out he had not yet returned to China and never did. PEN Center USA West, along with PEN Centers around the world, began going through the names of Chinese writers taken into custody so we might intervene. I remember well reading through these names written in Chinese sent from PEN’s London headquarters and trying to sort them and get them translated. Liu Xiaobo, I am certain must have been among them, though I didn’t know him at the time.

In his Final Statement to the Court twenty years later, Liu told the consequence for him of being found guilty of “the crime of spreading and inciting counterrevolution” at the Tiananmen protest: “I found myself separate from my beloved lectern and no longer able to publish my writing or give public talks inside China. Merely for expressing different political views and for joining a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher lost his right to teach, a writer lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual could no longer speak openly. Whether we view this as my own fate or as the fate of a China after thirty years of ‘reform and opening,’ it is truly a sad fate.”

I finally did meet Wei Jingsheng after years of working on his case. He was released and came to the United States where we shared a meal together at the Old Ebbit Grill in Washington. I was hopeful I might someday also get to meet Liu Xiaobo, or if not meet him physically, at least get to hear more from him through his poetry and prose.

His words are now our only meeting place. His writing is robust and full of truth about the human spirit, individually and collectively as citizens form the body politic. I expect that both his poetry and the famed Charter 08, for which he was one of the primary drafters and which more than 2000 Chinese citizens endorsed, will resonate and grow in consequence….[cont]

December 23, 2018: Pause…Watch…Listen…See…Hear

As we slide into the holidays and sweep towards the new year, events are in a swirl and spiraling mostly downwards it would appear, at least in Washington, DC where I live.

Photo Credit: Julia Malone

Stop! A voice insists in my head.

Pause. Watch. Listen.

Turn off the car radio, the tv news, the commentators, the politicians, at least for a moment.

Go to the park. Or to the country. Allow space to receive other thoughts.

Hear the wind rustling through a green bush at the edge of the parking lot.

See the wind knocking off the last leaves of a tree.

Watch the flag, still at half mast, saluting the wind.

Remember the three-year-old on stage last night at the community theater, trying to keep up and match steps with the older children.

Enjoy the three dogs—black, blonde and brown retrievers—running across the open field.

Hear the carols: “Sleigh bells ringing…Lovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you…”

No sleighs in Washington, but the carols ring out, and traditions wrap around in old words and sentiments even as new words—”border wall, shutdown, impeachment, resignation, fraud, lies”—fill the public discourse.

Time to get out of town?

Or just time to pause, watch, listen and try to see and hear other harmonies.

Giddy up! Giddy up! Let’s go. Looking for the Wonderland of Snow!

Happy holidays to All!

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

December 2019: [Beginning in May 2019 I started writing a retrospective of work with PEN International for its Centenary so posts were more frequent in 2019-2020. In December 2019 there were two posts in the PEN Journeys. The PEN Journeys series completed in October 2020.]

December 11, 2019: PEN Journey 14: Speaking Out: PEN’s Peace Committee and Exile Network

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

With a blue glacial lake surrounded by the Alps, a small island in the center with an ancient church with a Wishing Bell that rang out and promised fulfillment for the wishers, with a castle perched atop a hillside—with beauty and history intertwined through the landscape, Bled, Slovenia offered a stunning venue for PEN International’s Peace Committee meetings.

Bled, Slovenia

In the heart of Europe, the Peace Committee sat in the heart of a contradiction, for there were few places less peaceful than the Balkans. Yet Slovene PEN members played an important role as did other PEN members in bridging divides among writers in conflict zones.

At the Peace Committee’s inception in 1984, Slovenia was part of Yugoslavia, one of a handful of Communist countries after World War II whose writers were able to sign PEN’s Charter which endorsed freedom of expression. The other countries included Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Hungary. In 1962 a well-known Slovene writer, who was a member of English PEN but returned each year to Slovenia, championed the idea of resurrecting the Slovene PEN center which had existed before the war as well as the other two Balkan PEN Centers—Croatia and Serbia.

In 1965 writers from these Yugoslav centers took on the task of staging an International PEN Congress in Bled. At the congress Arthur Miller presided as the first and only American President of International PEN. At the ’65 Bled Congress PEN also hosted for the first time Soviet writers as observers. “Almost despite myself I began feeling certain enthusiasm for the idea of international solidarity among writers, feeble as its present expression seemed,” Miller wrote in his autobiography Timebends. “…I knew that PEN could be far more than a mere gesture of goodwill.”

It took almost 25 years before a Soviet, and later Russian, PEN Center emerged. [see PEN Journey 3, 6, 8] During the Cold War it was difficult for writers from the East and West to communicate, but at PEN congresses and meetings and at the Peace Committee, writers debated, exchanged ideas and shared literature. The Peace Committee became a haven during the Balkans War and also a meeting ground for writers from other conflict areas.

Unlike the Writers in Prison Committee which worked to protect and liberate individual writers, it was difficult at times to define the concrete actions the Peace Committee could take, but at least three stand out in my memory—one direct action, one initiative and one rigorous debate on a pressing issue.

As noted in an earlier post [PEN Journey 7] the head of Slovene PEN, Boris Novak ran the barricades during the Balkans War with aid for writers in the besieged Sarajevo as did Slovene poet and future Peace Committee Chair Veno Taufer and others. At the Peace Committee meeting in 1994 Boris reported 100,000 DEM ($60,000) had been contributed from PEN centers around the world and delivered to almost 100 Bosnian writers in order to save lives. When a new Bosnian center was elected at PEN’s Congress in late 1993, the Bosnian center began taking over the delivery of aid, and Boris was elected chair of the Peace Committee.

Boris Novak. Photo credit: The Bridge Magazine

Veno Taufer. Photo Credit: Alchetron

I attended my first Peace Committee Conference as Chair of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee in 1994 at the midway point of the Sarajevo siege. At the time PEN was also being asked to help writers who managed to get out of the city. In London I’d met one of these Bosnian writers and gave him my son’s old computer which he accepted as if I’d given him the keys to the city for he had no means to write. Writers fleeing not only the Balkans but situations in Africa and the Middle East needed support as they landed in new locations. It was at the Peace Committee meeting in 1994 that PEN’s Exile and Refugee Network was first conceived in partnership with the Writers in Prison Committee. The initiative was confirmed at the PEN Congress later that fall in Prague….[cont]

December 18, 2019: PEN Journey 15: Speaking Out: Death and Life

As I wrote holiday cards for the prisoners on PEN’s list this year, I recalled the many cases of writers PEN has worked for over the decades—the successes when writers were released early from prison and the sorrow when they did not survive. The path back for a writer imprisoned for his work is rarely easy, at times has led to exile, but often is accompanied by a mailbag full of cards and letters from fellow writers around the world.

I also sat with PEN’s Centre to Centre newsletters spread around me from 1994-1997, the years I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). During that period if a country was mentioned, I knew whether writers were imprisoned there and often knew the main cases as did PEN’s researchers. At the time we published twice a year PEN’s list with brief descriptions of the cases. Proofing paragraph after paragraph of hundreds of situations, I would know without looking when I had moved from one country to another by the punishments given. Lengthy prison terms up to 20 years to life meant I was reading cases from China, but if the writers were suddenly killed either by government or others, I’d moved on to Columbia. In Turkey were pages and pages of arbitrary detentions and investigations and writers rotating in and out of prison.

Names from this period are a kind of ghost family for me, evoking people and a time and place: Taslima Nasrin, Fikret Başkaya, Mohamed Nasheed, Gao Yu, Bao Tong, Hwang Dae-Kwon, Myrna Mack, Ma Thida, Yndamiro Restano, Mansur Rajih, Luis Grave de Peralta, Brigadier General José Gallardo Rodríguez, Koigi wa Wamwere, Eskinder Nega, Tefera Asmare, Liao Yiwu, Ferhat Tepe, Dr. Haluk Gerger, Ayşe Nur Zarakolu, Ünsal Öztürk, İsmail Beşikçi, Eşber Yağmurdereli, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Đoàn Viết Hoạt, Nguyễn Văn Thuận, Balqis Hafez Fadhil, Tong Yi, Christine Anyanwu, Tahar Djaout, Aung San Suu Kyi, Yaşar Kemal, Alexander Nikitin, Faraj Sarkohi, Ali Sa’idi Sirjani, Wei Jingsheng, Chen Ziming, Slavamir Adamovich, Bülent Balta, and many more. Many are now released, a few are even working with PEN, a number have deceased and two of the most celebrated and tragic—Liu Xiaobo and Ken Saro-Wiwa—were executed, one left to die in prison, the other hung.

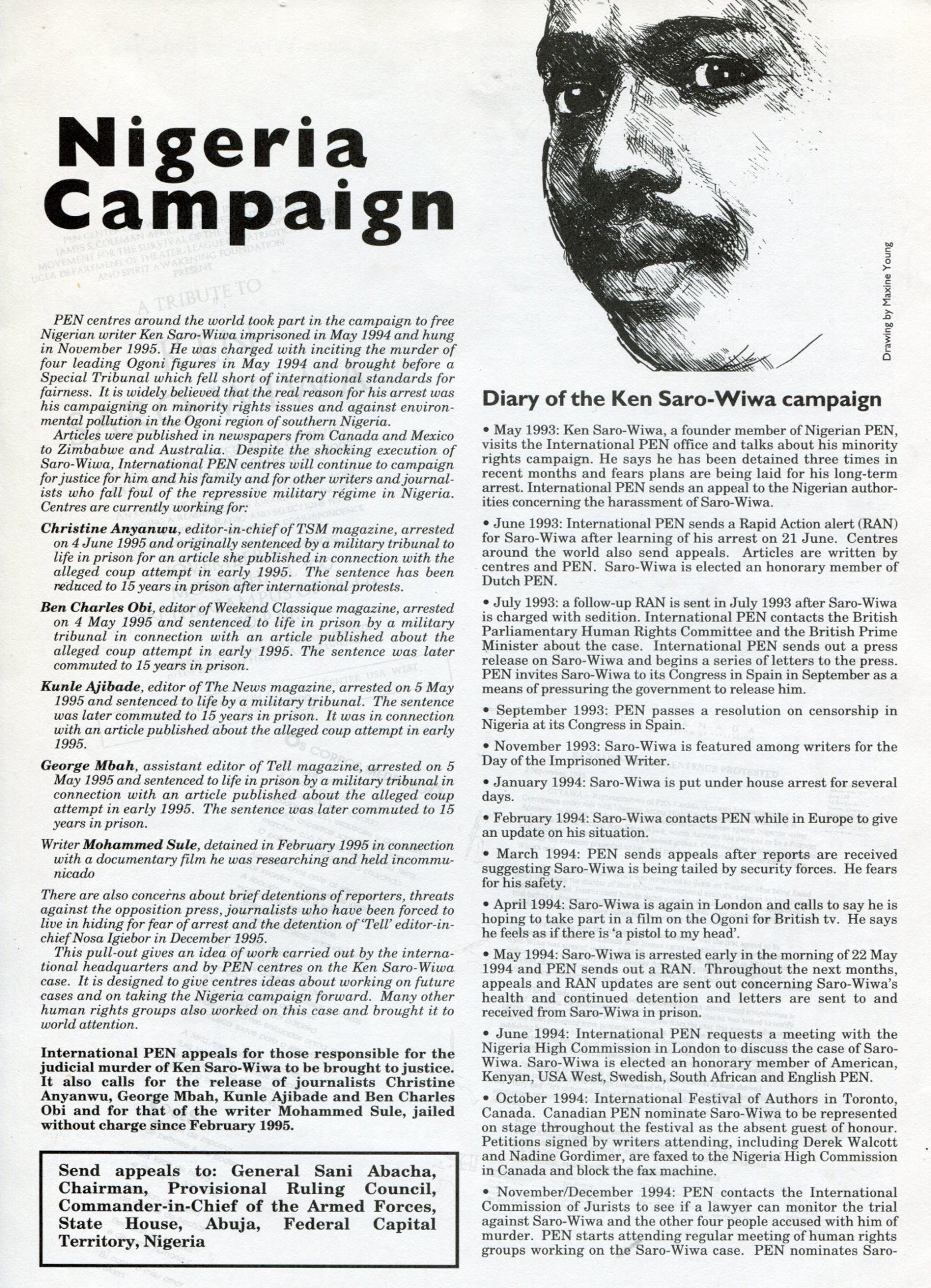

Page 1 of PEN International’s campaign for Ken Saro-Wiwa 1994-1996

In their cases, no amount of mail or faxes or later emails or personal meetings with ambassadors and diplomats changed the course for these writers. A year before Ken Saro-Wiwa’s death, noted Iranian novelist Ali Sa’idi Sirjani died in prison. And years later the murder of Anna Politkovskaya in Russia and the murder of Hrant Dink in Turkey and in 2017 the death in prison of Chinese poet and Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo all stand out as main cases where PEN and others organized globally but were unable to change the course. I’ll address the case of Liu Xiaobo in a subsequent blog. He was also in prison during the 1990’s but was not yet the global name and force he became.

One of the most noted of PEN’s cases in the mid 1990s was Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa who was hanged November 10, 1995. Ken understood they would hang him, but PEN members did not accept this. Ken was an award-winning playwright, television producer and environmental activist who took on the government of Nigerian President Sani Abacha and Shell Oil on behalf of the Ogoni people whose land was rich in oil and also in pollution and whose people received little of the profits.

I was living in London when Ken Saro-Wiwa, who had been arrested before for his writing and activism, visited PEN and other organizations in support of the Ogoni cause. PEN took no position on political causes but campaigned for his freedom to write and speak without threat. He met at length with PEN’s researcher Mandy Garner, providing her books and documentation of how he was being harassed in case he was arrested again. When he returned to Nigeria, he was arrested again and imprisoned in May 1994, along with eight others, and charged with masterminding the murder of Ogoni chiefs who were killed in a crowd at a pro-government meeting. The charge carried the death penalty.

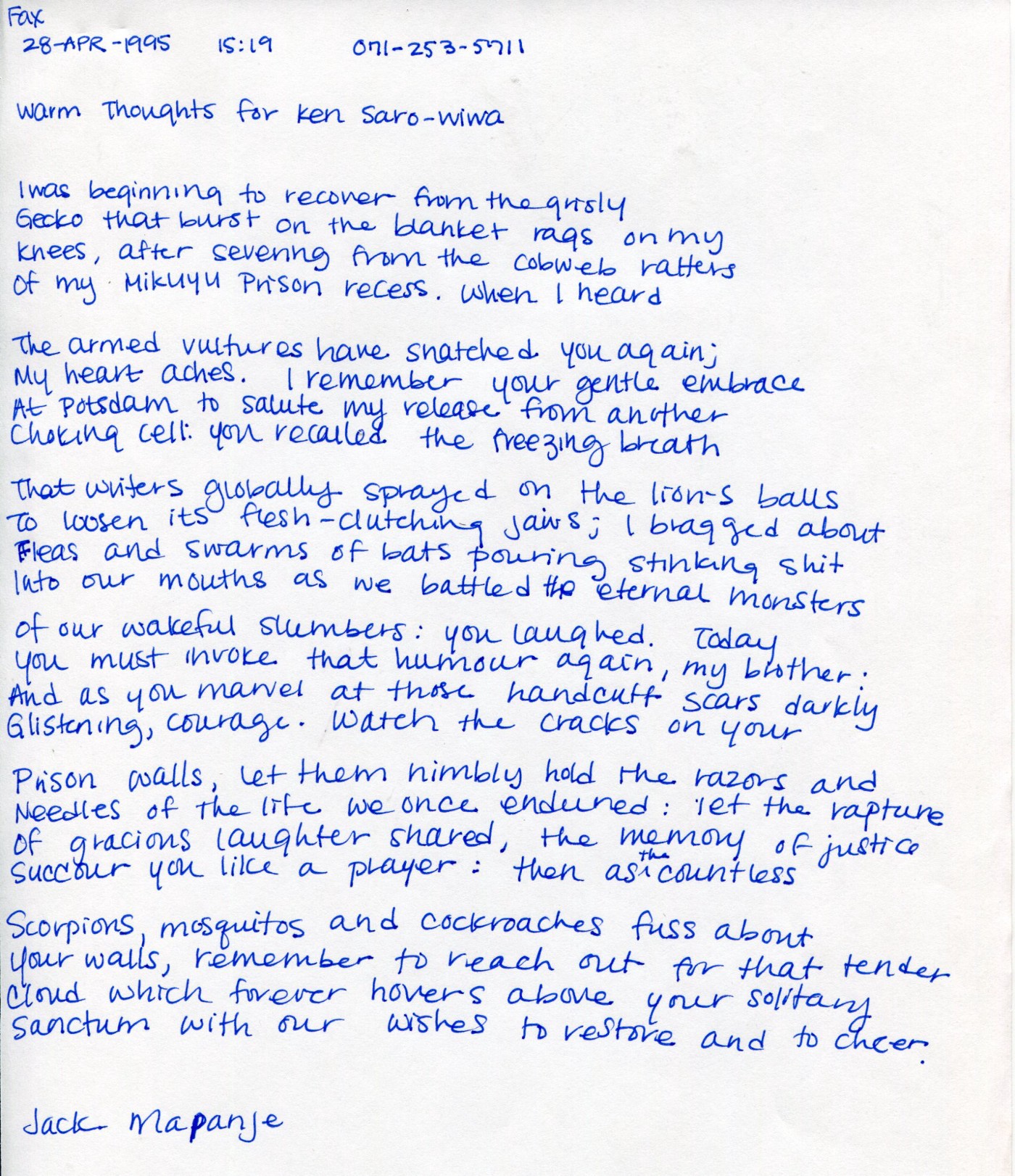

Poem from Malawian poet Jack Mapanje to Ken Saro-Wiwa published on page 2 of PEN Campaign document above

PEN mobilized quickly and stayed in close contact with his family. Mandy worked tirelessly on the case, gathering and coordinating information and actions. Ken Saro-Wiwa was an honorary member of PEN centers in the US, England, Canada, Kenya, South Africa, Netherlands, and Sweden so these centers were particularly active, contacting their diplomats and government officials. At PEN International we met with members of the Nigeria High Commission; novelist William Boyd joined the delegation. “I remember sitting opposite all these guys in sunglasses wearing Rolex watches, spouting the government line,” Mandy recalls. We also talked with ambassadors, including from England, the US and Norway to encourage their petitioning of the Abacha government. We met with Shell Oil officials to ask that they intervene to save Ken Saro-Wiwa’s life. PEN USA West also had lengthy meetings and negotiations with Shell Oil. PEN International and English PEN set up meetings in the British Parliament where celebrated writers spoke. English PEN mounted candlelight vigils outside the Nigerian High Commission which writers including Wole Soyinka, Ben Okri, Harold Pinter, Margaret Drabble and International PEN President Ronald Harwood attended. A theater event in London featured Nigerian actors acting out extracts from Ken’s plays and also reading poems from other writers in prison. Taslima Nasreen spoke as well. Ken’s writing was made available to the press which covered the story widely.

The activity in London mirrored activity at PEN’s more than 100 centers around the globe, from New Zealand to Norway, from Malawi to Mexico. From every continent signed petitions were faxed to the Nigerian government of General Sani Abacha and to the writers’ own governments, to members of Commonwealth nations, to the European Union, the United Nations and to the press calling for clemency for Ken Saro-Wiwa. Through the International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) of which PEN International was a founding member, the word spread to freedom of expression organizations worldwide. Other human rights organizations including Amnesty and Greenpeace also protested. No one wanted to believe in the face of such an international outcry that the generals in Nigeria, particularly Nigeria’s President Sani Abacha, would kill Ken Saro-Wiwa….[cont]

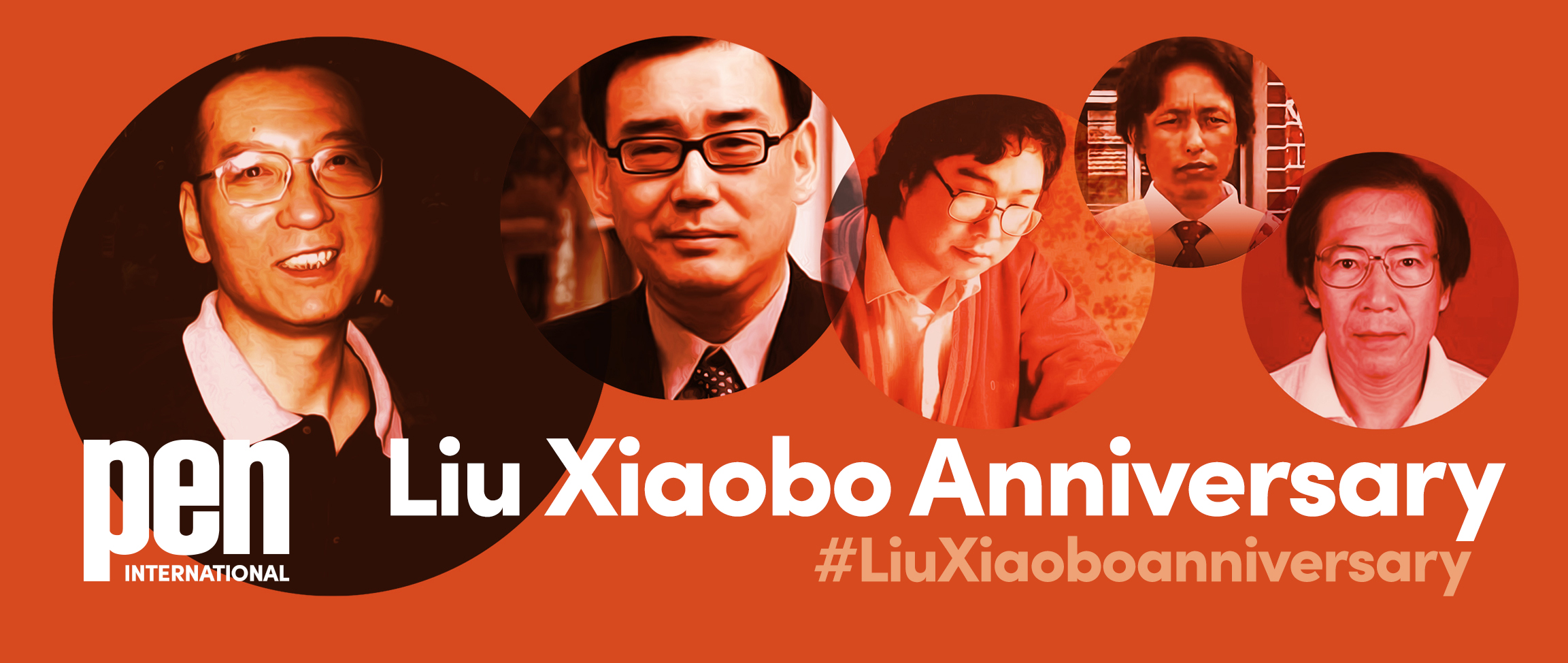

December 4, 2020: Nobel Peace Prize for Liu Xiaobo Ten Years After

PEN International marks the ten-year anniversary of the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to writer, literary critic and human rights activist Liu Xiaobo on 10 December 2010. PEN’s Liu Xiaobo Anniversary Campaign acts as a commemoration of Liu Xiaobo’s life, his contribution to Chinese literature, and his selfless work promoting basic freedoms in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The campaign also highlights the cases of writers Gui Minhai, Kunchok Tsephel, Yang Hengjun and Qin Yongmin who are currently detained by the PRC government. The campaign seeks to raises awareness of their situation, to boost advocacy work on their behalf and to ensure that they and their families feel supported and not forgotten.

The following links to PEN’s campaign. Below is text and Chinese translation of my video tribute to Liu:

Hello, I’m Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Vice President Emeritus of PEN International.

您好!我是乔安尼•利多姆-阿克曼,国际笔会荣休副会长。

Ten years ago, essayist, poet, activist and PEN member Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace. Liu envisioned and worked towards a peaceful and democratic pathway for China. Beginning with the protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and through the subsequent decades, he spoke out and wrote and gathered people and ideas in support of a China where individual freedom was valued and protected.

十年前,散文家、诗人、活动家、笔会成员刘晓波成为首位荣获诺贝尔和平奖的中国公民。刘先生设想并致力于中国走向和平民主的道路。他从1989年天安门广场抗议运动开始,在随后数十年言说和书写,并聚集民众及理念,以支持一个重视和保护个人自由的中国。

In 2008, he and others drafted Charter 08, which set out this democratic vision. He and others gathered hundreds and then thousands of signatures from Chinese citizens who endorsed the vision. Charter 08 did not call for an overthrow of the government so much as a transformation of the way government related to its citizens in a transition to a democratic society that would include freedom of expression and assembly.

2008年,他和其他人起草了《 零八宪章》,阐明这一民主愿景。他们从支持这一愿景的中国公民那里汇集了成百上千人签名。 《零八宪章》并未呼吁推翻政府,而是要转变政府相对于公民的方式,转型为包括言论自由和集会自由的民主社会。

Liu Xiaobo has been called the Nelson Mandela or Václav Havel of China because of his ideas, his activism and his leadership. Like Havel, Liu was committed to nonviolent action as a means of achieving change, and he was an inspired writer.

刘晓波因其理念、言行和领导能力而被称为中国的曼德拉或哈维尔。像哈维尔一样,刘晓波也致力于以非暴力行动来实现变革,他是一位受鼓舞的作家。

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

I first encountered Liu Xiaobo through PEN. After the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989, PEN worked on behalf of the writers who had been arrested in the protest, including Liu Xiaobo. Liu had also been instrumental in persuading students to leave the Square before the soldiers and tanks rolled in to attack and possibly kill them. At the time of Tiananmen Square, I was President of PEN Center USA West. A few years later when Liu was again imprisoned for his writing, I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee.

我首先通过笔会遭遇刘晓波。在1989年天安门广场镇压后,笔会致力于代表在抗议活动中被捕的作家,包括刘晓波。刘晓波还曾劝说学生离开广场,以免士兵和坦克席卷攻入广场可能杀死他们。在天安门广场抗议时,我担任美国西部笔会会会长。几年后,当刘晓波再次因写作而被监禁时,我是国际笔会狱中作家委员会主席。

Liu Xiaobo then went on to become one of the founders and the second President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), whose members lived inside and outside of China. He was instrumental in establishing the platforms by which these writers could communicate and share ideas about a society where freedom of expression and democratic processes could exist.

刘晓波随后成为独立中文笔会(ICPC)的创始人之一和第二任会长,该笔会成员居住在中国境内和海外。他发挥作用建立起这个平台,这些作家们可以借此平台,交流和分享有关这样一个社会的理念,在那里言论自由和民主进程得以存在。

During the time Liu was President of ICPC, I was the International Secretary of PEN. However, Liu was not allowed out of mainland China into Hong Kong where ICPC had its meetings, and I didn’t get to the mainland until in 2010 after he was arrested for the fourth and final time, so we never met in person, though over decades I have worked with many of his colleagues.

在刘晓波担任独立中文笔会会长期间,我曾担任国际笔会秘书长。然而,他没获准离开中国大陆前往独立中文笔会举行会议的香港,而直到他 第四次也是最后一次被捕后的2010年,我才去中国大陆,因此我们从未亲身见面,尽管数十年来我一直与他的许多同事共同工作。

Liu Xiaobo was the writer the Chinese government feared the most and therefore arrested. Liu was charged as “an enemy of the state” for “incitement of subverting state power” because of his ideas, his writing and his participation in the drafting and circulating of Charter 08. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison. He was the only recipient of the Nobel Prize who was in prison at the time and not allowed to attend the ceremony. Only an empty chair represented him. His wife Liu Xia was also not allowed to attend. Liu Xiaobo died in custody July 13, 2017.

刘晓波是中国政府最害怕的作家,因此而被捕。由于其理念、写作并参与起草和传播《 零八宪章》,刘晓波被指控为“煽动颠覆国家政权”的“国家敌人”。他被判处了十一年徒刑。他是当时在监狱中而未被允许参加颁奖典礼的唯一诺贝尔奖得主,只有一把空椅子代表他。他的妻子刘霞也被禁止出席。刘晓波于2017年7月13日去世。

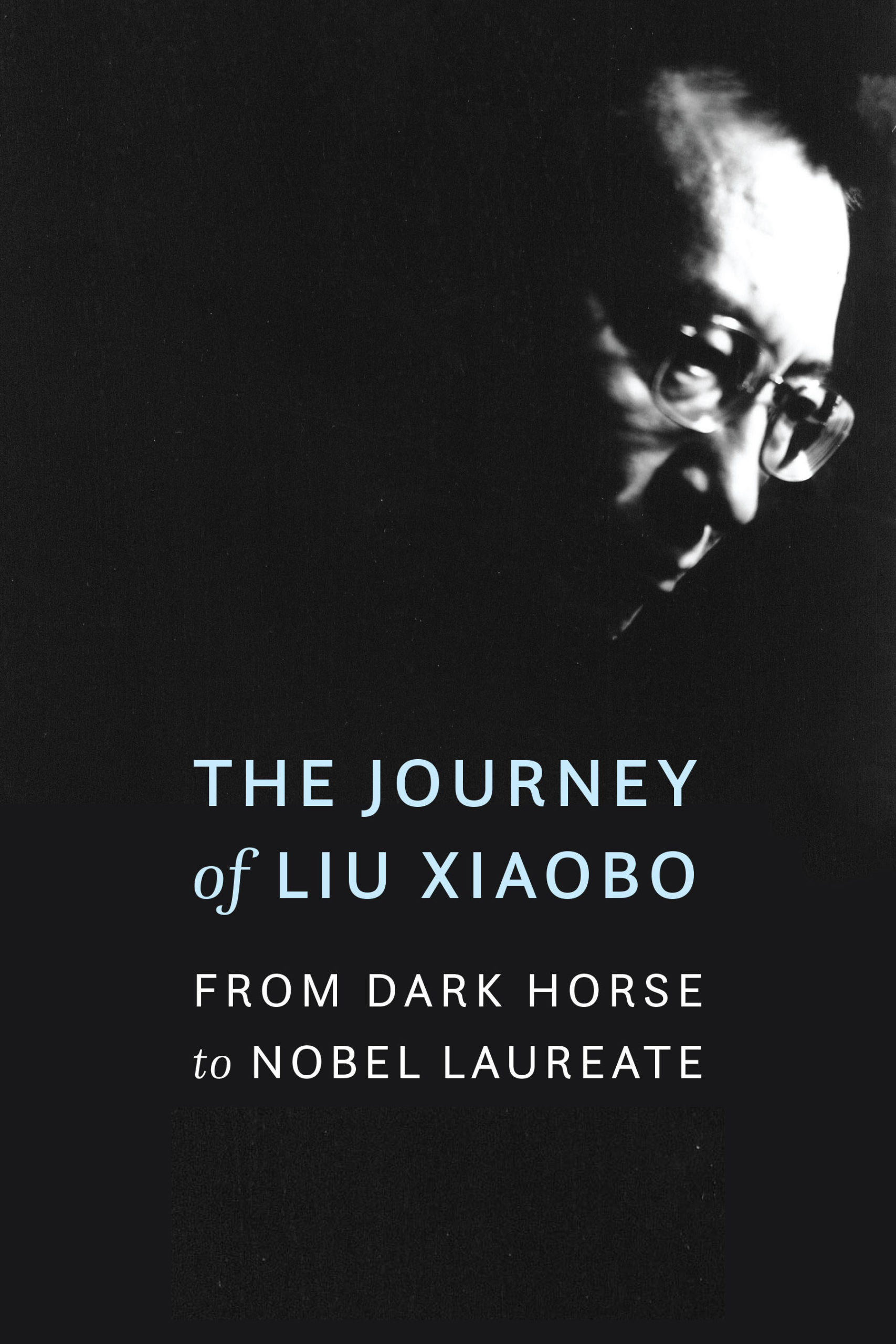

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

他去世后,全世界了解他的作家开始书写他及其作品,书写中国以及自由主义和民主理想之路。今年出版了《刘晓波之旅程:从黑马到诺奖得主》(文文版),包含75篇以上的文章,可能是来自中国民主活动人士的最大笔墨聚会,既是对刘晓波的回忆致敬,也是对中国民主运动的研究。

China’s Democracy Movement and Liu Xiaobo’s legacy still inspire those inside and outside of China, from the mainland to Xinjiang to Tibet to Hong Kong and to neighboring countries engaged in the struggle for political reform and an end to authoritarian rule.

中国民主运动和刘晓波的遗产,仍然激励着中国内外的人们,从大陆到新疆,到西藏,再到香港,再到争取政治改革和结束专制统治的邻国。

[cont]

December 14, 2020: I have a better feeling about tomorrow…

I am living in the country for the first length of time in my life. I wake up most mornings to light lifting the sky out my bedroom window which faces east—a vibrant red line on the dark horizon. Slowly the color fades to orange then yellow and then a pale pink as the sun sneaks up behind the land across the river.

As the sky grows lighter, I stumble out of bed, bundle up and go downstairs, make a quick cup of tea, turn on the fire pit and sit outside with my dogs to watch the world fill with light before the sun itself appears, a throbbing yellow globe through the trees. Some mornings a cloud settles on the horizon, and I see only the effect of the sun—light cast upward, shimmering pink splashes on the clouds above until the sun finally emerges through the clouds and greets the day.

As the sky grows lighter, I stumble out of bed, bundle up and go downstairs, make a quick cup of tea, turn on the fire pit and sit outside with my dogs to watch the world fill with light before the sun itself appears, a throbbing yellow globe through the trees. Some mornings a cloud settles on the horizon, and I see only the effect of the sun—light cast upward, shimmering pink splashes on the clouds above until the sun finally emerges through the clouds and greets the day.

I listen to the geese waking up, honking to each other before they take flight. An American flag blows on a flagpole by the river. On a windy day it flaps wildly and on other days it luffs in the breeze.

For the past year I have been living on the Eastern Shore of Maryland where oyster and crab boats quietly troll by on the river in their season. I live in the area near where James Michener wrote his doorstop-size novel Chesapeake. In fact our good friends, two of the few people we have seen regularly during this pandemic year, live in the house where Michener wrote his book.

For the first months here, I listened to Michener’s Chesapeake every day at lunch as I took a break from writing. For ten months, I have eaten the same lunch—tomato soup, rice crackers with melted chips of cheese, hard-boiled egg, grapes and frozen yogurt bar—and the same breakfast—coconut yogurt with blueberries, raspberries and slivered almonds and cup of decaf coffee—and though dinner varies, usually a salad with another hard-boiled egg, maybe tuna, few more rice crackers, another frozen yogurt. I eat the same meals because I don’t like to cook and have little imagination when it comes to food, so without planning, the routine has meant that everything again fits me in my closet. I bike every morning on a stationary bike and swim most afternoons after work is done.

Swimming at dusk and sitting by the fire pit at dawn are the particular times when I listen. I try to hear the harmony in the universe, not the arguing of political opinions nor the statistics of covid nor the rancor nor the violence of citizens intolerant with each other.

I look up at the sky and listen. On more than one occasion, clouds have broken open and a shaft of light has fallen on the water, or a pageant of clouds has swept across the blue with the wind rising, or some days the air is so still I can hear the river flowing. Nature reminds me there is a larger perspective, and if I listen, there are harmonies to hear, inspired thoughts to think. Hearing the harmony comes first and then…

I have a better feeling about tomorrow.

(Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman)

Wonderful post, Joanne! Love the concept and your photos. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you, Maryann. Happy holidsys!

I have been abiding with hedgehogs for almost a year, in icon forms, without fully knowing why. Now I do. This hedgehog’s life is mindfulness—living it, exercising it, teaching it (on hiatus from latter due to pandemic). Gratitude to Thich Nhat Hanh, who just died, with whom I began this path in my 20s. Between your and your sons’ ages/generations, I missed you until this morning’s wikipedia search, sparked by Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia, led me here. I inexplicably long to go to Turkey, sail the Bosphorus. Will be reading your and Elliott’s books during the coming months. Thank you, Joanne, for who you are, for your life’s work (and play).