Tempus Fugit/Carpe Diem!

This week PEN International came together virtually for its annual Congress with writers from around the world. What was to have been a large celebratory gathering in Oxford and London for PEN’s Centenary, disaggregated into voices and pictures on a screen from every corner of the globe. Some had easier internet access than others, but the majority of PEN’s 155 centers were at least able to zoom in for portions of the celebration and for the election of a new PEN International President, Turkish novelist Burhan Sönmez as well as three new board members and new Vice President William Nygaard.

After serving six years as the first woman President of PEN International, Jennifer Clement stepped down, heralding PEN’s work on freedom of expression and “the unique revolutionary value of literature in the transformation of individual lives and societies.” In taking on the presidency, Sönmez warned against a new epidemic of authoritarianism in the world and also emphasized the importance of literature and imagination and PEN’s work protecting the freedom of writers to imagine and create.

A hundred years go the first president of PEN John Galsworthy said in a toast at PEN’s first dinner: “We writers are in some sort trustees for human nature. If we are narrow and prejudiced, we harm the human race.” At its Centenary Congress PEN reaffirmed the commitment made in a “Statement of Arms,” approved by London PEN in 1926: “The P.E.N. Club stands for hospitality and friendliness among writers of all countries; for the unity, integrity and welfare of letters; and concerns itself with measures which contribute to these ends. It stands apart from politics. We affirm that PEN is a place of hospitality for all writers without exception and a space of kinship among colleagues. We work for the unity of letters through dialogue and translation. We stand apart from politics and political regimes with the mission of defending freedom of expressing, linguistic rights and equality.” In the 5th PEN Congress in 1927, these principles evolved into the first three articles of the Charter of PEN.

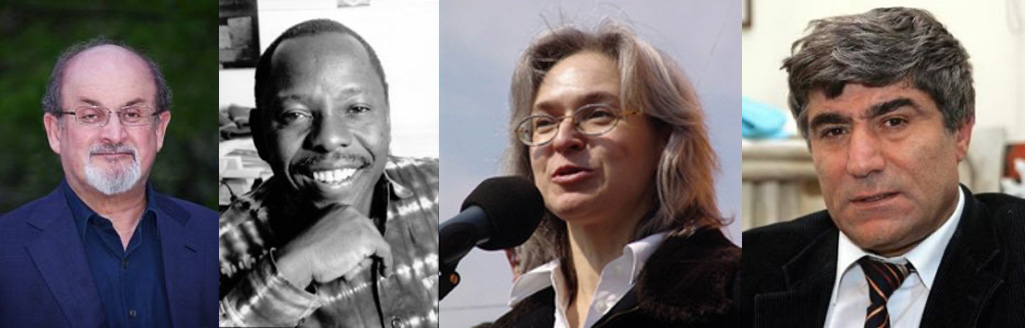

PEN’s Centenary Congress featured discussion with longtime voices in PEN, including Margaret Atwood, Orhan Pamuk, Boris Novak, Salman Rushdie, John Ralston Saul, Homero Aridjis, Per Wastberg, Eugene Schoulgin, Ngugi wa Thiong’o and J.M. Coetzee and testimonies from former PEN cases Enoh Meyomesse, Can Dundar, Dareen Tatour and Ma Thida, who was elected as the new chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee.

Resolutions were passed protesting the situations in Myanmar, Belarus, Nicaragua, and Israel. Two new centers of PEN were welcomed—PEN Malta and PEN Quechua Bolivia.

In the past month we have witnessed some withering scenes, particularly in Afghanistan where just eighteen years ago, PEN was able to open a center which grew into a vibrant home for literature and culture with the publication of over 500 manuscripts of Afghan writers, men and women from all backgrounds. Today finds many of these members in peril; some have been killed, and many are in hiding or fleeing. As has been the case in other countries, we hope and work for sanctuary to be found and hope eventually new life can be nurtured and flourish.

Tempus fugit—the Latin expression attributed to Ovid and to his contemporary Virgil—is corollary to the Latin carpe diem! The flight of time and the seizing of the day seem apt exhortations for this period especially as the conventions of the pandemic continue to keep us apart and at the same time impel the most creative use of new technologies to connect us with each other.

This month I am again posting a retrospective of blogs. (Readers can click the date and title to read the full post or click the “cont.” note at the bottom.) These September essays begin in 2008. The geography ranges over work and writing from Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, China, Japan, Turkey, South Korea, Iceland, the U.S., Sweden, Ukraine, Russia, Spain, Slovenia, Germany, Denmark, Senegal, and Mexico. They are journeys of the heart and mind over 13 years and of many air miles. By contrast, I took my first plane ride in 18 months last week, from Washington, DC to Boston.

Sitting in my chair by a river with a portable desk in my lap, I range in my thoughts over the globe with the continued hope of us all reconnecting next year.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

September 30, 2008: African Snapshots

Nigerian Night

The night sky swarmed with pale insects like snowflakes fluttering outside the window of the airplane as it landed at the small airfield in Northern Nigeria. At first they looked like moths, but they were hundreds…thousands of grasshoppers diving into the headlights and fuselage of the plane. Were they cruising the night sky, interrupted by our descent, or had the lights and the hum of the airplane drawn them to their end?

Inside the terminal a luggage belt creaked as bags were pushed one at a time through a small portal onto a set of rollers. When the lights went out and the terminal fell dark, we waited, but the power didn’t return. One by one cell phones flipped open– small arcs of light aimed at the weathered belt as the passengers from Lagos searched for their bags. Dragging suitcases behind us, holding cell phones in front of us to light the way, we plunged into the warm night.

I was in Nigeria as a board member of Human Rights Watch which held meetings there last year. We spoke with government officials after a dubious presidential election. We met with lawyers and human rights activists and teachers and judges and other members of civil society. See HRW reports on Nigeria. We brought experience, research, and expectations. We gained further experience, laid out the expectations, found bridges and absorbed the cacophony of the night.

Tanzanian Morning

On the eastern edge of Africa on the coast of Tanzania the sun rises out of the Indian Ocean like a giant topaz transported from the sub-continent. Around the sun the ocean crashes against the rocks on the coast of Dar es Salaam.

After breakfast I climb into a four-wheeled drive vehicle to go outside the city to visit schools in the countryside where children and teachers are reading and writing and telling stories in Kiswahili and making books to share with other children in the local language. The Children’s Book Project, started in Tanzania in 1991 and has assisted in bringing hundreds of books to publication, distributed these paperback readers into schools, set up libraries in the schools, and trained teachers and artists on how to write and illustrate books and how to teach with these readers. The schools where the CBP is involved have regularly out-performed many of the schools in the country.

In one classroom students perform a story they have read in one of the storybooks. Tabu wa Taire was written by a teacher and tells of a young girl who doesn’t listen to her parents and prefers to play rather than work. One day she wanders too far from home and is captured by a man who puts her inside his drum. Her parents and the village look everywhere for her, but can’t find her until the man comes to their village to play his drum. Someone hears crying from inside the drum, and there the village finds and rescues the girl. The students act out this story for the class and the visitors and end with a celebratory concert on the drum and orange fantas all around.

Ugandan Afternoon

We drive through the bush along a narrow dirt road, the sun beating on the closed windows, the trees hanging down over the path, crowding the road on both sides so that the 4-wheel drive car is literally pushing back the brush as we plow carefully around the turns, occasionally dodging another car or long-horned cattle who amble across the one-lane road to graze on the other side.

We are several hours outside of the capital Kampala and over an hour off the main road, rocking from side to side in the dense undergrowth when suddenly we come to a clearing and a school. The school’s red earthen huts rise from the ground with tin roofs. There are no doors on the huts. There are few books here, and the learning materials hang from the ceilings so that the cows, who can wander in and out of these classrooms, won’t destroy them.

This school is for 75 children of pastoralists–families who make their living tending cattle, moving from place to place with their cows looking for grazing lands. The children usually travel with their parents and don’t have an opportunity to go to school. But here in the clearing, on land donated by one of the more successful in the community, a school has been built; the roofs have been donated by the son of one of the wealthier families. Teachers have been recruited and trained by Save the Children. The children in the school are studying in grade levels 1-4 with the hope that the school will be able to add grades as the children grow. Because there is a school, many of these families, at least the women, will stay in the area while the children attend classes. Some of the women are discussing how to keep the cows out of the classrooms.

September 30, 2009: China at 60–Fate of Liu Xiaobo?

On its 60th Anniversary, China is Still Crushing Freedom

Congress should pass Resolution 151 to speak out on behalf of arrested dissident Liu Xiaobo.

From The Christian Science Monitor

WASHINGTON – The People’s Republic of China celebrated its 60th anniversary today with massive military parades, fireworks, and concerts throughout the country. In mid-November, President Obama will make his first presidential visit to Beijing, marking the 30th anniversary of Chinese-U.S. relations with an agenda likely to include the environment, security, and the global economy.

In the time between these milestones, the fate of an individual Chinese citizen hangs in the balance and may well foreshadow future relations with China. Liu Xiaobo, one of China’s leading writers, intellectuals, and dissidents, is expected to come to trial and be sentenced after the anniversary celebrations and before the president’s visit.

That’s why Congress must act quickly. The proposed Resolution 151 calls for Mr. Liu’s release and urges China to “begin making strides toward true representative democracy.” The resolution notes Liu’s own words: “The most fundamental principles of democracy are that the people are sovereign, and that the people select their own government.”

Resolution 151 should be passed with dispatch before Liu’s trial and sentencing so that it might signal to Beijing how much America cares about the lack of freedom in China. Liu was arrested last December and charged this June with “inciting subversion of state power” for his role as one of the principal drafters of Charter 08, a document that set out a democratic vision for China. Charter 08 was originally signed by more than 300 leading writers, engineers, teachers, workers, farmers – even former public servants and Communist Party officials. It was subsequently signed by more than 10,000 Chinese citizens. The document was circulated widely on the Internet, though it is now blocked in China.

Patterned after Charter 77, which demanded basic civil and political rights in Czechoslovakia when it was under Soviet domination, Charter 08 calls for nonviolent democratic change in China and for a government that recognizes that freedom “is at the core of universal human values,” and human rights are inherent, “not bestowed by a state.”

In a recent visit to Capitol Hill, writers from the Independent Chinese PEN Center, where Liu is a former president, as well as American writers, urged members of Congress to accelerate the passage of Resolution 151. The Chinese writers, who were in touch with Liu up until the day he was arrested, say that they believe a resolution by the US Congress would have a beneficial effect and help mitigate the severity of the sentence, which could be as much as 15 years. However, the resolution needs to pass before his trial and sentencing; otherwise it will come too late….[cont]

September 30, 2010: Full Moon Over Tokyo

Flying west 15 hours I never saw the sun set, but in the evening, between the skyscrapers of Tokyo, I glimpsed the full moon I’d left the night before shimmering on the Potomac, the same full moon beaming down over China, Myanmar, and Vietnam. I found myself contemplating whether the writers in prison in those countries could also glimpse the luminous golden light from a corner of their prison cells. I was in Tokyo for PEN International’s 76th Congress.

Writers from 90 centers of PEN gathered to discuss “The Environment and Literature—What can words do?” and to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, that particular group of writers who advocate on behalf of colleagues imprisoned, threatened or killed for the expression of their ideas.

In its history, PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee has been instrumental in getting the releases of such well known writers as Arthur Koestler, Wole Soyinka, Vaclav Havel as well as thousands of others in countries on every continent and from every political condition, from fascist regimes, communist regimes, marginal and faux democracies, wherever words were considered subversive and powerful enough to threaten. At the moment the most cases and the longest prison sentences for writers are in China, Myanmar, Vietnam and Iran, but writers are under threat in over 60 countries with the internet offering a new frontier for protection of free expression.

At the keynote ceremony of the PEN International Congress a play, Water Letters by Hisashi Inoue, dramatized the theme of the earth’s and mankind’s connectedness, especially through water. Human beings are largely made of water, and water—rivers, streams, oceans—links us all, the characters intoned. If the source of water is threatened in one area, there are repercussions in another. There is one earth, one people; the environment is in our hands.

The same can be said of freedom of expression. The 11-year imprisonment of Liu Xiaobo for urging democratic reform in China not only imprisons the man but the possibility of his next ideas. The imprisonment of writers in Myanmar and Vietnam, the more than 60 imprisoned writers, journalists, and bloggers in Iran affect the flow of ideas worldwide. The more than 50 journalists killed in Mexico chills freedom and undermines the rule of law beyond Mexico’s borders.

Yet ideas, like water, have a way of flowing around barriers and through bars and seep into the stream of thought if passed from one person to the other. And so writers outside prison pass on the work and writing of their colleagues.

Looking up at the moon, we contemplate the universe from the same point of focus and glimpse for a moment our connectedness.

September 28, 2011: Bridge Over the Bosporus: Citizenship on the Rise

The sun glints off the waves of the Bosporus as the wind skims across the surface of the water, and power boats, tourist ships and ferries cruise between the shores of Europe and Asia on Istanbul’s great waterway. I’ve arrived to an Indian summer in this city at the crossroads of Europe, Asia and the Middle East after a PEN International Congress an hour and a half away in Belgrade where the theme was Literature—Language of the World.

I’m here with purpose and meetings, but for the afternoon I have a few hours to sit on the banks of the waterway and write and contemplate the bridges linking the two continents and consider what it takes to construct and maintain a bridge.

While I’m in Istanbul, the newspapers have been filled with headlines about Turkey’s Prime Minister Erdogan’s trip to Libya, Egypt and Tunisia and his message to those involved in the Arab Spring. He urges the citizens to adopt “laicism” and become “laic states” like Turkey. (‘Laicism’ is the secular control of political and social institutions in society.) The message from this Muslim leader has stirred controversy, especially from neighboring Iran which has warned against the Western secular state.

The bridge at question here is a mighty and lengthy suspension bridge between religion and politics, between the state and its citizens. It swings over centuries of history. The concept of “citizen” wasn’t applicable for a large swath of history and geography and is still problematic in many countries which perceive their residents as serving the state and those in power, which often include the clergy, rather than the state and its leaders serving their citizens.

All one needs to do is wander through the grounds of the splendid and opulent Topkapi Palace, which Sultan Mehmed built after he conquered Constantinople (now Istanbul) in the fifteenth century. He declared the city as one of the three capitols of the Ottoman Empire and proceeded to spend the state’s treasury on the palace. Later others spent it on a lavish harem filled with women who only the Sultan had the right to visit. The Ottoman Empire, which stretched over two million square miles at its height and spanned over 600 years, bore the motto: “The Eternal State.”

A decade after the Sultan finished his new palace at Sarayburnu, Spanish trading ships sailed across the Atlantic and ran into a land they named America. Here ideas of citizenship would evolve and the residents of this new territory would challenge, along with those from other nations, the monarchies and empires of Europe.

The role and boundaries of citizenship continue to evolve. I remain hopeful that the full rights of all citizens might emerge in the uprisings in the Middle East. On the Bosporus I’m sitting now on the European side, and I see that the ferry I’ve been watching has arrived on the Asian shore.

September 15, 2012: North Korean Writers in a Land of the Rising Sun

I’m flying home from the 78th PEN International Congress in Gyeongju (Kyongju), South Korea, peering out the airplane window under the shade at the floor of clouds. The sun is just beginning to emerge above the horizon, turning the white billowing floor red as if fire were simmering beneath. On the horizon the orange-yellow line of sunlight glows then diffuses into the blue sky. The sun itself suddenly appears, a solid bold globe of fire, and the fire beneath the clouds grows dark.

However many sunrises I watch in however many circumstances—on airplanes, on a beach, in a city building, I take pause in wonder, breathe in and watch the larger movement of life.

Returning at 30,000 feet from a conference of writers from 85 PEN Centers around the world, I remember the first time I was in Korea 24 years ago—over 8700 sunrises ago. At PEN’s Congress in Seoul in 1988, a week before the Olympic Games security was high with bomb sniffing dogs and extensive car checks. The political environment was tense. Writers and publishers were in prison in South Korea, and PEN was divided on how to conduct its business in a country where freedom of expression was challenged. A contingent visited the writers in prison; I visited with the family of one of the writer/publishers. We lobbied inside and outside the official Congress for the freedom of these writers. After the Congress a number were released, including the one whose family I had visited.

Now 24 years later there are no writers or publishers in prison in South Korea. The PEN gathering in the mountainous city of Gyeongju, the ancient capital of the Shilla Dynasty where the rays of the rising sun first touch the land, focused instead on writers from North Korea, where there is no freedom….[cont]

September 16, 2013: Parallel Universe in a Glassed Concert Hall in Iceland

If you want to understand politics—it’s like being in a book club where everyone discusses the grammar.

So said actor/comedian Jon Gnarr, Mayor of Reykjavik, Iceland when he addressed the recent 79th PEN International Congress. Gnarr was elected Mayor in 2010 from the Best Party, which he and friends with no background in politics created as a satirical party after the economic meltdown in Iceland a few years ago. They won over a third of the seats on the City Council with a platform that included free towels in all swimming pools, a polar bear for the zoo and “all kinds of things for weaklings.” After he was elected, Gnarr declared he wouldn’t form a coalition government with anyone who hadn’t watched the TV series The Wire.

The politician with a short black tie, a sense of humor and a view of politics as a parallel universe resonated with the audience of over 200 writers at the Opening Ceremonies of the PEN Congress. Writers from 70 centers of PEN gathered to deliberate and debate literature and the situation for writers and freedom of expression around the world, a world they agreed often bordered on the absurd, but the absurd with serious consequences.

The Assembly discussed and passed resolutions on the challenges to freedom of expression in countries including Mexico, China, Cuba, Vietnam, North Korea, Eritrea, Belarus, Syria, Egypt, Turkey, Tibet, and Russia. The delegates walked en masse to the Russian Embassy to present their resolution protesting the recent legislation on blasphemy and “gay propaganda.” And they applauded the announcement during the Congress of the release of Chinese poet Shi Tao 15 months before the end of his 10-year sentence….[cont]

September 8, 2014: Boston on a Sunday Afternoon

The sun is shining. The swan boats are cruising on the pond in the Boston Commons. Joggers are jogging along the park. Children are running after ducks; parents are running after children. University students have returned en mass from summer so the hum of young people hums in Boston and its neighboring city of Cambridge, ever the student’s town. People from all backgrounds, speaking Spanish, Vietnamese, Arabic, French, Russian and languages I don’t recognize pass by as I sit on a park bench.

For a moment I don’t want to think about ISIS or terrorists’ attacks or the beheadings of writers, who are friends of people I know, writers and their families whom I can’t help but think about and want to honor, or to think about those who must decide what our country does next or those who will take the risk to do it.

All this is on my mind and on the minds of people in Washington where I live. But for a moment I look out and take a breath and watch Boston on a Sunday afternoon before the world accelerates, a few days before we mark again the events of 9/11. I want to savor and remember this moment just for a moment. It is the point after all.

September 25, 2015: Unity on the Potomac?

The Potomac is smooth as a mirror today. The wind occasionally dusts its surface. On lamp posts by the river, American flags catch a light breeze and flutter under an overcast sky. Fall is stirring in the air though joggers still run in shorts and tee shirts and students pace to the boathouse for afternoon rowing practice.

A mile form here Washington is recovering from two major State visits in four days—first Pope Francis and literally on his papal heels, Chinese President Xi Jinping.

But here on the river with a view of Memorial Bridge and the Kennedy Center, of the traffic cruising on Rock Creek Parkway and airplanes taking off from National airport, it is unusually quiet for a Friday afternoon. Couples stroll by. A mother with a pram stops and looks out on the gray-brown water. The city is perhaps letting out its collective breath. There have been no attacks, no disasters.

Washington has feted and listened—been told to unify for greatness by the Pope and then looked for common cause with the Chinese leader who has limited shared values and certainly not an agenda of individual freedom.

It is always an existential question whether America—“one nation under God with liberty and justice for all”—can live its ideals and live in the world.

From a political point of view, the right to dissent and the forums to express disunity are fundamental and the very evidence of a nation breathing, of a democracy working. No one is arrested or imprisoned for their disagreements. We have the freedom to be in gridlock though surely there is a better way to demonstrate freedom. The question ahead as political campaigns heat up is whether we can breathe and disagree and at the same time govern and guide.

The spiritual call for unity is one each citizen must find in his own sanctuary, not in the halls of Congress.

As I’m writing, I hear sirens whining in the distance growing louder and louder, and in front of me on this terrace overlooking the river, a great crane appears and a wall is literally lifted out of the walkway. I’m told these walls, which lay buried most of the time, were installed after the last great flood wiped out the waterfront. The waitress returns and tells me they are now raised on any threat of a flood. Down river floods have occurred and may be moving our way.

No blog posted September 2016

September 8, 2017: “Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred”

The train from Copenhagen airport to Malmö, Sweden took just half an hour across the 21st century Øresund Bridge, which spans five miles of water, then the train dove into 2.5 miles of tunnel. Looking out the window at farmland and the blue waters of the Baltic Sea, I imagined this journey was not so easy 74 years ago with Nazis in pursuit. In 1943 as the Nazis went to sweep Denmark’s 7800 Jews into concentration camps, Danish and Swedish citizens rallied, and 7220 people managed to escape in boats across this Sound to nearby Sweden. Thousands landed in Malmö where I was headed for a less dramatic, but still fraught, occasion.

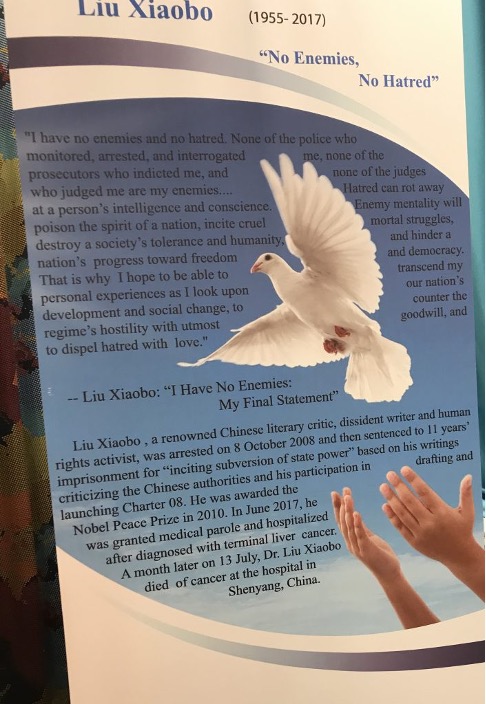

Members of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) whose writers live inside and outside mainland China were joining writers from Uyghur PEN, Tibetan PEN and members from Inner Mongolia, along with writers from PEN Turkey and Azerbaijan for the First International Conference of Four-PEN Platform: “Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred.” Swedish PEN was providing the safe space for debate, discussion and strategies of action on human rights and freedom of expression. Just six weeks before, one of ICPC’s founding members and honorary President Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo, died in a Chinese prison after serving nine years of an 11-year sentence for drafting Charter 08, a document co-signed by 308 writers and intellectuals calling for a more democratic and free China.

A recognized leader in China’s Democracy Movement, Liu Xiaobo’s loss was deeply felt. A number of the writers gathered knew and worked with Liu. Most knew at least one fellow writer in prison. Many now live in exile themselves. Almost half of PEN International’s writers-in-prison cases are located in the regions represented at the conference.

The theme “No Enemies, No Hatred”—drawn from Liu Xiaobo’s final statement at his trial—sparked the debate in Malmö.

The theme “No Enemies, No Hatred”—drawn from Liu Xiaobo’s final statement at his trial—sparked the debate in Malmö.

Keynote speaker Nobel Laureate Shirin Ebadi challenged, “But I do have enemies and I do feel hatred.” Facing death threats from her government in Iran, she had to leave everything behind at age 63 and move to London.

“Liu Xiaobo said he had no hatred and no enemies, but he also never compromised with any dictators,” she noted. “We must fight against dictators but our weapons are our pens and are nonviolent. We must not be silent. We can’t compromise with governments such as China who would eradicate an ‘empty chair’ from the internet.” [When Liu Xiaobo was unable to attend the Nobel ceremony because he was in prison, the Nobel Committee placed an empty chair on stage to represent him. The Chinese government is said to have censored the term “empty chair” from the internet in China.]

“What is the use of a pen if Liu Xiaobo is dead?” challenged one writer. Another speculated that if Liu Xiaobo had known how his life would end, he would have changed his message. A friend of Liu’s assured that he would not because for him no enemies and no hatred was a spiritual commitment….[cont]

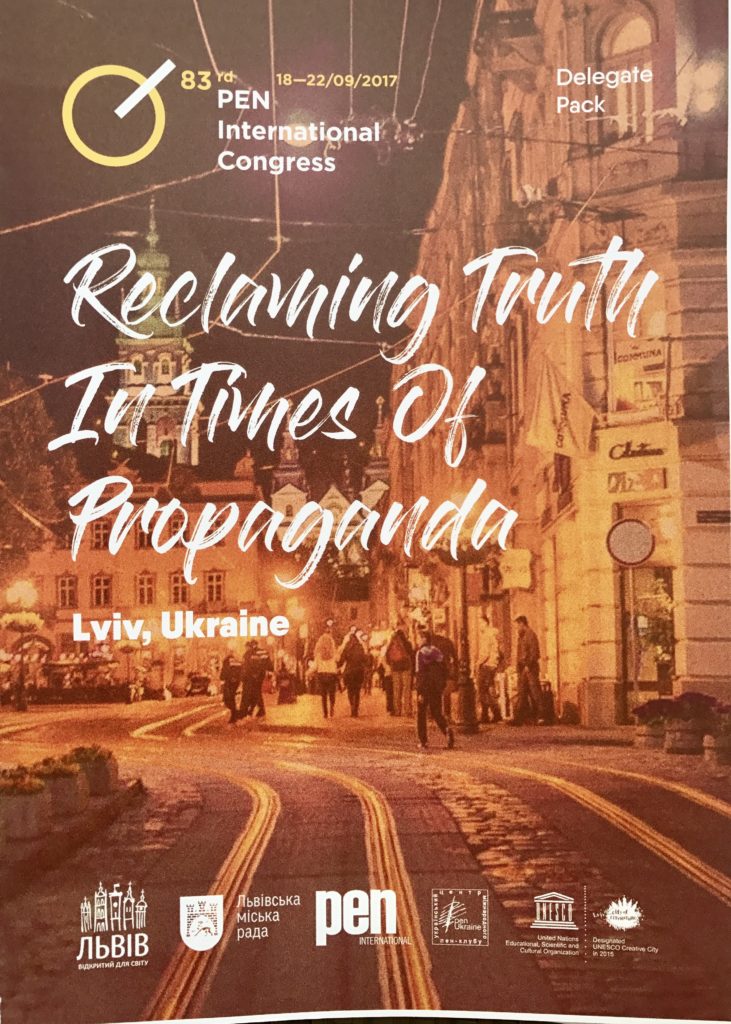

September 28, 2017: Reclaiming Truth in Times of Propaganda

PEN International’s 83rd Congress in Lviv, Ukraine took on truth and words, history and memory, women’s access and equality, cyber trolling, fake news and threats to freedom of expression worldwide, including public panels focused on the three super powers: “America’s Reckoning—Threats to the First Amendment in Trump’s America,” “China’s Shame—How a Poet Exposed the Soul of the Party,” and “Putin’s Power Play—The Decline of Freedom of Expression in Russia.”

At its annual gathering PEN hosted more than 200 writers, editors, staff and visitors from 69 PEN centers around the world in the historic city of Lviv, the Cultural Capital of Ukraine and a UNESCO World City of Literature. Straddling the center of Europe, on the fault lines between East and West, Lviv changed its name and governing domain eight times between 1914 and 1944, passing from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to Russia, back to Austria, Ukraine, Poland, Soviet Union, Germany then back to the Soviet Union and now finally in the Ukraine.

The path of European history cuts through the city and can be seen in architecture, culture and conversation. Though writers celebrated literature in the western Lviv, fighting was still underway in eastern Ukraine and the Crimea. PEN’s Russian center didn’t attend the Congress at the same time a new PEN St. Petersburg center was elected. Other new centers joining PEN’s network included Cuba, the Gambia and South India.

In times of war, the first casualty is truth, noted PEN’s report “Freedom of Expression in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine: External Aggressions, Internal Challenges.” The report and the Congress addressed the aggressive role of propaganda in conflict. In Ukraine, in Russia and worldwide there has been a proliferation of false narratives.

PEN’s report on Ukraine noted: “Despite significant improvements, democracy in Ukraine remains ‘a work in progress’ and, among other things, severe challenges to the enjoyment of the right to free expression remain. These include the use of the media to foster political interests and agendas, delays in reforming state-owned media; and intimidation and attacks on journalists followed by impunity for the perpetrators. On the other hand, public criticism is growing, albeit slowly, including demands for more transparent and unbiased journalism.”

In Russia authorities are taking increasingly extreme legal and policy measures against freedom of expression, according to a PEN/Free Word Association report “Russia’s Strident Stifling of Free Speech.”

No writers are in prison in Ukraine, but in the Crimea, which Russia annexed in 2014, filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, an opponent of annexation, was arrested and is now serving a 20-year sentence inside a Russian prison on terrorism charges he denies. At PEN’s Assembly, delegates remembered Pavel Sheremet with an Empty Chair. A Belarusian-born Russian journalist and free speech advocate, Sheremet wrote for an independent news website and hosted a radio show where he reported and commented on political developments in Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. He died in a car bomb explosion in Kiev July 2016. Shortly before he was assassinated, he’d written about corruption among law enforcement in Belarus, Ukraine and propagandists in Russia. His murder remains unsolved….

PEN also passed a Women’s Manifesto noting “the use of culture, religion and tradition as the defense for keeping women silent as well as the way in which violence against women is a form of censorship needs to be both acknowledged and addressed.”

At the Opening Ceremony author of East West Street Philippe Sands, whose grandfather was born in Lviv, narrated the origins of international human rights law and the concepts “crimes against humanity” and “genocide.” These legal frameworks were developed by two lawyers who passed through the very university where the delegates sat. The legal teams prosecuting at the Nuremberg trials after World War II used these frameworks to secure convictions, including the conviction of Hans Frank, Hitler’s lawyer who governed the area around Lviv and sent over 100,000 Jews to concentration camps and death.

“The Foundations of human rights law came from here,” Sands said. “Every individual has rights under international law.” The lawyers Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin studied at the university at different times but never met. One escaped to Austria then England, the other to America. Lauterpacht protected the rights of the individual with the concept he developed of “crimes against humanity” and Lemkin protected the group with the legal construct for “genocide.” Both men were on the legal teams that successfully secured convictions at Nuremberg.

“No organization in the world knows better than PEN the need to protect individuals and to protect others,” Sands concluded….[cont]

Jennifer Clement, PEN International President

Andrei Kurkov from Ukranian PEN and Carles Torner, Executive Director PEN International

No blog posted September 2018

September 2019: [Beginning in May 2019 I started writing a retrospective of work with PEN International for its Centenary so posts were more frequent in 2019-2020. In September 2019 there were two posts in the PEN Journeys and in September 2020 there were four.]

September 3, 2019: PEN Journey 8: Thresholds of Change…Passing the Torch

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

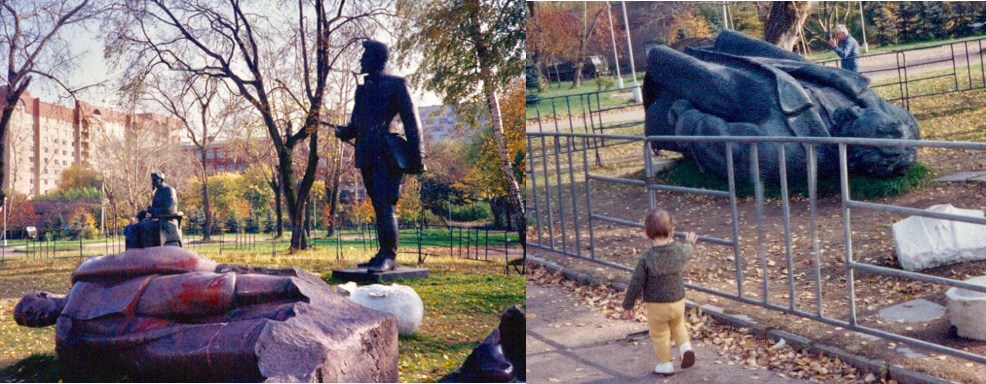

In fall, 1991 I went to Moscow just months after the August coup attempt in which hardline Communists sought to take control from President Mikhail Gorbachev. I hopped onto the visa of my husband who was traveling to Russia as a Visiting Scholar at the International Institute of Strategic Studies in London. I went as a writer, interested in meeting other writers. I contacted fellow PEN member and Russian translator Michael Scammell, who had previously chaired International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). Michael gave me a list of writers to contact in Moscow.

Statues toppled of Lenin and Stalin and others in park after failed coup attempt in Moscow, 1991.

My husband and I stayed in what I was told was one of the government hotels where guests were hosted but also watched. We were watched too, I’m fairly certain, though there was little for anyone to see with me. I was cautious as I made contact with the writers lest my reaching out compromise them. Only a few years before, PEN’s case list had included many dissident Soviet writers in prison. Michael and later WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack and PEN’s WiPC committees around the world had advocated for the release of dissident Soviet writers, many of whom were imprisoned in the gulags. PEN had also covertly sent aid to them and their families through the channels of the PEN Emergency Fund.

Stall of street vendor selling Russian Matryoshika dolls, including stacking dolls of Boris Yeltsin and Mikhail Gorbachev and also U.S. Presidents.

I no longer remember if I called or faxed the writers in advance. (Fall, 1991 was before an active internet.) I likely made contact when I arrived. The writers welcomed me. We met in simple apartments with old holiday cards on the mantles as decorations, a paper mobile hanging from the light fixture over one dining room table I recall, strips of newspaper stacked by the toilets in lieu of tissue. The economy was spare for these writers. They hoped for change and for freedoms to come, but they were cautious. In these meetings and in other random encounters, people were curious about the United States. On the street, vendors not only sold Russian nesting dolls with the rushed visages of Boris Yeltsin, who had defied the tanks of the coup, and of Gorbachev but also stacking dolls of U.S. presidents, including one set that had George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. I was asked by numbers of people, including the writers, if I could get them copies of the U.S. Constitution and the Federalist papers. The Berlin Wall had fallen and times were changing, but no one knew how that change would settle out in the Soviet Union.

I remember one meeting in Moscow with members of a women’s theater cooperative—actresses, director, costume designer, and playwright. Before the member who spoke English arrived, we were left to communicate with each other by hand gestures and a few common words. Finally, the sturdy, broad-chested Russian writer who spoke English entered. I asked her what she did during the coup attempt. She stood, spread out her arms and declared triumphantly, “I stopped the tanks with my breasts!” This image has stayed with me, along with her words and the determined words of her fellow thespians and writers in that apartment, women demanding as their due freedoms they hadn’t yet experienced….[cont]

Joanne and members of Russian women’s theater cooperative in Moscow apartment, 1991.

September 20, 2019: PEN Journey 9: The Fraught Roads of Literature

Twelve-foot puppets danced outside the dining room’s second floor windows at our hotel, billed as the “oldest hotel in the world,” set on the central plaza of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, the venue for PEN International’s 60th Congress.

Sara Whyatt, coordinator of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, and I hurried to finish breakfast and our agenda before we joined the crowds outside at the historic Festival of St. James. That evening International PEN’s 60th Congress would convene. Hosted by Galician PEN, the Congress had as its theme Roads of Literature, which seemed appropriate as pilgrims from around the world also gathered on the Obradoiro Plaza in front of the ancient Cathedral, the destination for their Camino.

Parador Hotel, Santiago de Compostela St. James Festival, Obradoiro Plaza, Santiago de Compostela

At this Congress the presidency of PEN was changing hands as was the chairmanship of the Writers in Prison Committee, which I was taking over from Thomas von Vegesack. Ronald Harwood, the British playwright, was assuming the PEN presidency from Hungarian novelist and essayist György Konrád, who had been a philosophical president, often running the Assembly meetings like a stream of consciousness event where the agenda was a guide but not necessarily a governing map. Ronnie ran the final meeting like a director and dramatist, determined to get the gathering from here to there with a path and deadline. Both smart, experienced writers, committed to PEN’s principles, they had very different styles. Known only to a few of the delegates a surprise visitor was also arriving mid-Congress.

The 60th Congress in September 1993 was a watershed of sorts. It was the first since the controversial Dubrovnik gathering six months before which had split PEN’s membership (see PEN Journey 8) because of the war in the Balkans.

Konrád’s opening speech to the Assembly explained that PEN’s leadership had gone ahead with the congress over the many objections from PEN centers because the venue had been approved earlier by the Assembly and the host center had been unwilling to postpone. He acknowledged the widespread criticism and also the concern that some individuals who fomented the Balkan wars and participated in alleged war crimes were writers who had been members of PEN. He said, “That these men of war also include men of letters, indeed that these latter are well represented, painfully confronts our professional community with the notion of our responsibility for the power of the Word. Nationalist rhetoric led to mass graves here, and there. Mutual killings would not have been on such a scale in the absence of words that called on others to fight or that justified the war.”

György Konrád, PEN International President 1990-1993, Credit: Gezett/ullstein bild, via Getty Images

Konrád’s address at the opening session went a way in bringing the delegates together. “What we can do is to try and ensure the survival of the spirit of dialogue between the writers of the communities that now confront each other….International PEN stands for universalism and individualism, an insistence on a conversation between literatures that rises above differences of race, nation, creed or class, for that lack of prejudice which allows writers to read writers without identifying them with a community…

“Ours is an optimistic hypothesis: we believe that we can understand each other and that we can come to an understanding in many respects. The existence of communication between nations, and the operation of International PEN confirm this hypothesis…PEN defends the freedom of writers all over the world, that is its essence.”

Ronald Harwood, PEN International President 1993-1997. Credit BAFTA

Ronald Harwood added in his acceptance for the presidency: “The world seems to be fragmenting; PEN must never fragment. We have to do what we can do for our fellow-writers and for literature as a united body; otherwise we perish. And our differences are our strength: our different languages, cultures and literatures are our strength. Nothing gives me more pride than to be part of this organization when I come to a Congress and see the diversity of human beings here and know that we all have at least one thing in common. We write…We are not the United Nations…We cannot solve the world’s problems…Each time we go beyond our remit, which is literature and language and the freedom of expression of writers, we diminish our integrity and damage our credibility…We don’t’ represent governments; we represent ourselves and our Centres…We are here to serve writers and writing and literature, and that is enough…And let us remember and take pleasure in this: that when the words International PEN are uttered they become synonymous with the freedom from fear….”[cont]

September 2, 2020: PEN Journey 40: The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World

At the end of September 2005 a Danish newspaper published 12 editorial cartoons which depicted Mohammed in various poses as part of a debate over criticism of Islam and self-censorship. Muslim groups in Denmark objected, and by early 2006 protests, violent demonstrations and even riots erupted in Muslim areas around the world. The offense was the “blasphemy” of drawing Mohammed in the first place and the particular mockery of some of the depictions in the cartoons.

The uproar over the Jyllands-Posten Mohammed cartoons quickly drew PEN into the controversy, first through Danish PEN and then through the International PEN office and other PEN Centers. PEN included many Muslim members and numbers of centers in majority Muslim countries. All PEN members and centers endorse the ideals stated in the PEN Charter. However, the third and fourth articles of the Charter which addressed the situation, also at times appeared to contradict each other:

Article 3: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

Article 4: “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world toward a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restrain, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

PEN International Board and Staff 2006. L to R: Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Elizabeth Nordgren (Finish PEN), Jane Spender (Programs Director) Sara Whyatt (Writers in Prison Committee Director), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Karen Efford (Programs Officer), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International President), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Britta Junge-Pederson (Treasurer), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair), Chip Rolley (Search Committee Chair), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Peter Firkin (Centers Coordinator) [not pictured: Mohammed Magani (Algerian PEN), Karin Clark (WiPC Chair), Kata Kulavkova ( Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair)

At the Peace Committee conference that April, I observed, “The Charter of PEN asserts values that can appear contradictory, but represent the dialectic upon which free societies operate and tolerate competing ideas…In our 85th year, International PEN still represents that longing for a world in which people communicate and respect differences, share culture and literature, and battle ideas but not each other….”[cont]

Peace Committee program 2006. Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Veno Taufer (Peace Committee Chair)

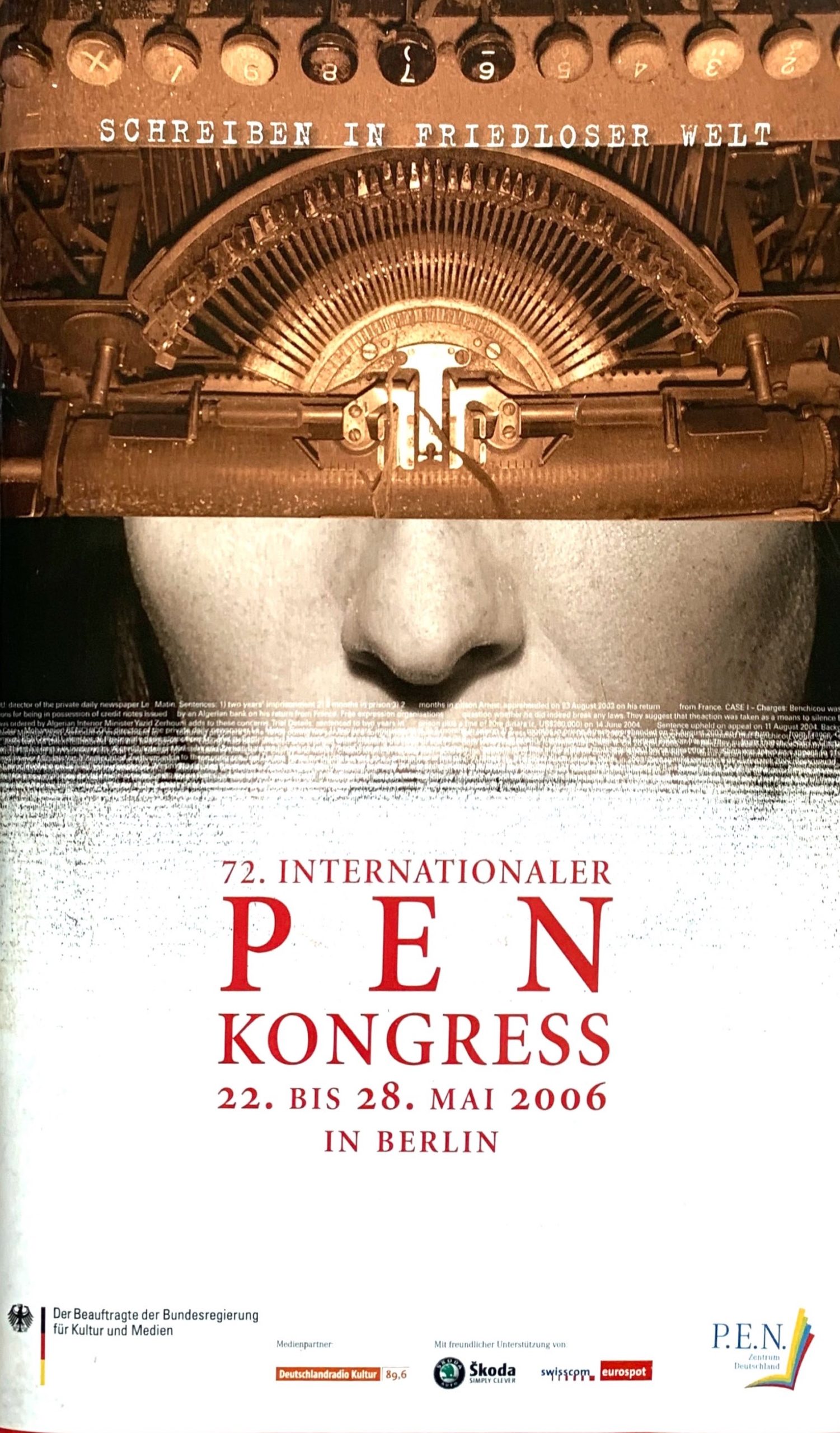

September 9, 2020: PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

I first visited Berlin in the fall of 1990 just after Germany reunited. I was living in London and took my sons, ages 10 and 12, to witness history in the making. I returned on a number of occasions, researching scenes for a book, attending meetings, and visiting German PEN in preparation for PEN’s 2006 Congress. Each time Berlin’s face was altered as the municipalities east and west moved to become one city again.

PEN International’s 72nd World Congress, Berlin, 2006

At the time of PEN’s Congress in May 2006, Berlin was bedecked with water pipes above ground—pink, green, blue, red—before the city buried its plumbing and infrastructure beneath the streets. Portions of the city had the appearance of an amusement park; there were also sections of the Berlin Wall with its colorful graffiti still standing, more as art exhibit than stark barrier to freedom.

“Welcome to a United Berlin” the German PEN President headlined his letter to the 450 delegates and participants for PEN’s 72nd World Congress. The Congress theme “Writing in a World Without Peace” was challenged by the reunification of Berlin and Germany, a historic event which bode well for the prospects of peace and which stood in contrast to the history that had come before. Yet the globe was still in conflict in the Middle East, in Asia and in Latin America where writers were under threat.

“There are countries such as Iran, Turkey or Cuba, where authors are jailed because of their books,” noted International PEN President Jiří Gruša. Resolutions at the Congress addressed the situations for writers imprisoned or killed in China, Cuba, Iran, Mexico, Russia/Chechnya, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, and other countries.

Left: Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) meeting at Berlin Congress. Karin Clark (Chair WiPC) and Sara Whyatt (WiPC Program Director). Right: WiPC Conference in Istanbul: Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN/PEN Board), Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Jonathan Heawood (English PEN), Notetaker

Two months before in March, over 60 writers from 27 PEN centers in 23 countries had gathered for International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul where the WiPC planned a campaign against insult and criminal defamation laws under which writers and journalists were imprisoned worldwide. The conference also addressed the recent uproar over the Danish cartoons, impunity and the role of internet service providers offering information on writers, especially in China. A working group formed to support the Russian PEN Centerwhich was under pressure from the Russian government.

Berlin, however, was sparkling and filled with the energy of reunification. “Today, this city—once separated by a Wall most drastically manifesting the division of Germany and Europe—has not only been re-established as the capital of Germany, but has simultaneously turned into a thriving meeting-place between East and West and North and South,” welcomed Johano Strasser, German PEN President. “Here in Berlin, history in all its facets—from the great achievements of German artists, philosophers and scientists to the crimes of the Nazis—has left its mark on the urban landscape.”

PEN’s 72nd Congress marked PEN’s 85th Anniversary and was a grand occasion. Chancellor Angela Merkel hosted a reception at the Chancellor’s office. President of the Federal Republic of Germany Horst Kohler gave the welcoming address at the Opening Ceremony, noting, “If Germany is the nation of culture that it intends to be again, then we have to stand up and fight for freedom of language, art and culture….”[cont]

Left: German Chancellor Angela Merkel addressing PEN members at 72nd PEN Congress, 2006; Right: PEN International President Jiří Gruša speaking to PEN delegates and members at the Federal Chancellery; front row: German PEN President Johano Strasser, Chancellor Angela Merkel and PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman. [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

September 14, 2020: PEN Journey 42: From Copenhagen to Dakar to Guadalajara and in Between

Royal Danish Library extension in Copenhagen, dubbed the Black Diamond (Photo by © User:Colin / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66870365)

Arriving in Copenhagen in early September 2006, I walked along the waterfront, dodged bicycles and shared coffee and conversation with longtime colleague Niels Barfoed, former President of Danish PEN who had briefly succeeded me as Writers in Prison Chair and was an eminent Danish journalist and writer. We met at the new waterfront extension of the Royal Danish Library, dubbed the Black Diamond because of its imposing black granite cladding and irregular angles. Niels would be moderating a public meeting on Freedom of Expression in the Arab World.

PEN International’s base was broadening in the Middle East and in Africa, both regions where active centers for writers were fragile, but potentially important havens. Danish PEN was hosting a conference with a dozen writers from the Arab-speaking world, including representatives from Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, Palestinian PEN, Tunisia, Lebanon and invited writers from Iraq and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), along with Danish and Norwegian PEN members and International PEN represented by Centers Coordinator Peter Firkin and myself.

The Copenhagen conference had been initiated in part as a response to the Danish cartoons controversy earlier in the year and also as an opportunity to develop PEN’s work and presence in the Middle East. PEN had a few centers in the region and interest from writers in Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, and Bahrain to form additional PEN centers and a desire to revive PEN Lebanon. Developing PEN centers in these areas was challenging given the politics and conflicts on the ground.

Ekbal Baraka, President Egyptian PEN (left) and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, PEN International Secretary (right) meeting in Cairo, 2006

The Copenhagen meetings explored common fields of interest among Western and Arab writers, networking among Arab writers and ways in which PEN could assist. Women writers in the Arab world had particular challenges, a discussion led by Egyptian PEN President Ekbal Baraka. Ekbal later became Chair of PEN International’s Women Writers Committee. Algerian PEN and International PEN board member Mohamed Magani offered to host a subsequent meeting in Algiers the following fall, along with a conference on translation. A public event in the evening showcased the work of the visiting writers….[cont]

Anna Politkovskaya, Russian journalist assassinated, 2006

A few weeks after the Copenhagen conference, my phone rang early on Saturday morning October 7, 2006 at my home in Washington, DC. Sara Whyatt, PEN International’s Writers in Prison CommitteeDirector, was on the line. She called to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya, Russian journalist, PEN member who’d visited PEN Congresses and meetings, who’d worked for years reporting on Chechnya—had been assassinated. The report was that Anna had been shot that morning in the elevator of her apartment building in Moscow.

For seven years Anna had been one of the few reporting on the war in Chechnya despite intimidation and violence. She had been arrested by the Russian military and suffered a mock execution; she’d been poisoned while flying from Moscow to the Beslan school hostage crisis and had to turn back to get medical treatment. She had survived many dangerous encounters. But now she had been killed.

The killing of Anna Politkovskaya swept through the news media around the world as well as through the PEN world. We were stunned and deeply saddened and then began our protests and calls for investigation, along with human rights organizations worldwide. PEN honored Anna at its subsequent Congress and meetings and annually held an Anna Politkovskaya lecture on the anniversary of her death to commemorate her fortitude and inspiration.

The work in PEN was a helix of hope and pain and sorrow and hope again….[cont]

September 28, 2020: PEN Journey 43: Turkey and China—One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward

January 2007 began with an assassination. The Board of PEN International was just gathering in Vienna for the first meeting of the year when board member Eugene Schoulgin got a phone call letting him know that our colleague and his friend Turkish-Armenian editor Hrant Dink, had been gunned down in Istanbul and killed. Many of us had seen Hrant at the PEN Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul in March.

Editor-in-chief of the bilingual Turkish-Armenian newspaper Agos, Dink had long advocated for reconciliation between Turks and Armenians and for Turkey’s recognition of the Armenian genocideearly in the century. Dink had received death threats before and had himself been prosecuted for “denigrating Turkishness,” but as with Russian colleague Anna Politkovskaya, Dink’s assassination stunned us all and set off widespread protests in Turkey and abroad. Eventually a 17-year old Turkish nationalist was arrested and convicted, but not before police were exposed posing and smiling with the killer in front of a Turkish flag.

PEN International Board Meeting, Vienna, January 2007. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary; Jiří Gruša, International President; Caroline McCormick, Executive Director; Judy Buckrich, Women Writers Committee Chair; Elizabeth Norgdren, Finish PEN; Eugene Schoulgin, Norwegian PEN; Franca Tiberto, Search Committee Chair; Sibila Petlevski, Croatian PEN; Britta Pedersen, International Treasurer; Eric Lax, PEN USA West; Mohamed Magani, Algerian PEN; Kata Kulavkova, Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair; Frank Geary, Programs; Karen Efford, Programs.

The work of PEN is, at its heart, personal. It is writers speaking up for and trying to protect other writers so that ideas can have the freedom to flow in society. In league with other human rights organizations, PEN also advocates to change systems that allow attacks and abuse. At times the work can feel ephemeral when the systems don’t change, or make progress only to regress. However, the individual writer abides, and PEN’s connection to the writer stands.

During my tenure working with PEN, Turkey and China have been the two countries that have imprisoned the most writers. For a period both nations appeared to be advancing towards more open societies but soon retreated. In the early 2000’s as Turkey aspired to join the European Union, the country operated as a democracy with a more independent judiciary; fewer writers became entangled in the judicial processes. However, in 2007 the democratic transition in Turkey began to veer off courseand has continued a downward spiral towards authoritarianism ever since.

China also promised to become a more open society with the advent of the Olympic Games in 2008. Democracy activists inside and outside of China grew hopeful. In this climate, PEN held an Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in Hong Kong in February 2007; it was PEN’s first in a Chinese-speaking area of the globe. Over 130 writers from 15 countries gathered, including writers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and many of PEN’s nine Chinese-oriented centers as well as members from Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Nepal, Australia, the Philippines, Europe, and North America.

Both China’s and Turkey’s Constitutions protected freedom of expression in theory, but in practice the protection was lacking. Instead, laws and regulations prohibited content. In Turkey, exceptions included criticism of Ataturk, expressions that threatened “unitary, secular, democratic and republican nature of the state” which in effect targeted issues around Kurds and Kurdish rights. In China, the Constitution noted that “in exercising their freedoms and rights, citizens may not infringe upon the interests of the State, of society or of the collective, or upon the lawful freedom and rights of other citizens.” The state was the arbiter….[cont]

One of the more creative campaign tools planned during the conference was spearheaded by a team of PEN Centers in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia. The members developed a digital relay with Chinese poet Shi Tao’s poem June. The poem tracked the path of the Olympic torch across a digital map. Shi Tao was serving a 10-year prison sentence for sharing with pro-democracy websites a government directive for Chinese media to downplay the 15th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests. His emails had been turned over to the Chinese government as evidence by Yahoo. His poem commemorated the Tiananmen Square massacre and was translated and read in the languages of PEN’s centers around the world, including in regional dialects as well as in the major languages. Ultimately 110 of PEN’s 145 centers participated and translated the poem into 100 languages, including Swahili, Igbo, Krio, Tsotsil, Mayan. The poem’s journey began on March 30, 2008 in Athens and traveled to every region on the online map, arriving in Hong Kong on May 2 and in June to Tibet where it was translated into Tibetan and the proposed Uyghur PEN center translated it into Uyghur. Finally August 6-8 it arrived in Beijing where it was translated and read in Mandarin. Anyone could click on the map and hear the poem in the language of the country designated.

By the 2008 Olympic Games 39 writers remained in prison in China.

June

By Shi Tao

My whole life

Will never get past ‘June’

June, when my heart died

When my poetry died

When my lover

Died in romance’s pool of blood

June, the scorching sun burns open my skin

Revealing the true nature of my wound

June, the fish swims out of the blood-red sea

Toward another place to hibernate

June, the earth shifts, the rivers fall silent

Piled up letters unable to be delivered dead.

(Translated by Chip Rolley)

Time of Repose and Preparing

It is a blustery August day on this fulcrum between summer and fall when the breeze stirs with a hint of the season ending. A pandemic stretching 18 months continues to unhinge life from what is considered normal, if there ever was normal. Life is far from normal in Afghanistan or Haiti right now. Normal is a relative term, residing perhaps in the hope for a measure of peace, for supply of basic needs and for the kindness of others.

This month I am again posting a retrospective of August blogs with a view of the last thirteen years’ history, a history which I read with nostalgia, recognizing those times are gone. It is difficult to imagine getting on a plane now to Tanzania or Kyrgyzstan or Macedonia with the same confidence of work to be done and the ability to meet those on the other end also engaging. The world may return as it was, though I’m not sure life ever returns as it was. But I hope it will transition to a world still connected and willing to connect and build with each other.

The geography of these posts range from Tanzania to Turkey to Qatar to France to Slovenia to Kyrgyzstan to Ghana to Macedonia and several in the United States. Readers can click on the date and title to read the full post. I am halfway through a year of posting these retrospectives and note that August is the first month where I’ve posted every year. I’m struck by the sultry beauty of this month between seasons, a time of repose and preparing.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

August 31, 2008: From the Edge of the Indian Ocean

I’m sitting looking out at the Indian Ocean from the eastern edge of Africa in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. It is Labor Day, at least in the U.S., though in the U.S. it is actually still Sunday night; but here it is morning with billowing white clouds, blue sky, palm trees, sun shining through—the end of winter in the Southern Hemisphere.

It took 17 hours of flying and a few hours of waiting in Amsterdam—roughly 20 hours to get here. When I arrived in the hotel room last night and the bellman turned on the TV, the BBC in a pulsating picture and sound was reporting on the approach of Hurricane Gustav to New Orleans and the interruption of the Republican National Convention. Was this important news in Tanzania? It was, in any case, the BBC news, and I was interested but couldn’t help but note how far one can go and still have America follow.

Outside the window in the hotel this morning, men are cutting the grass by swinging machetes across the lawn. From a distance it looks as if they are practicing their golf swings, but in the morning sun they are tending to the grass without lawn mowers or power tools.

In the following days here and in Uganda I’ll have the opportunity to visit schools and projects where educators and writers are responding to the shortage of books for children, particularly books with stories relevant to the children and books in local languages. This morning I’m aware of the stories we carry with us, the narrative in our heads wherever we go, the power of this narrative in shaping our lives and the importance of listening to the stories of others and opening up the narrative.

“Once upon a time in a place where the sun usually shines and the winds blow through the palm trees, there is a little girl who lives on the edge of the Indian Ocean, and every morning when she wakes up, she…”

August 31, 2009: Turkey Can Avert a Tragedy on the Tigris

It can develop energy and progress into the future without washing away the town of Hasankeyf, its jewel of the past.

From The Christian Science Monitor

Washington – In the southeastern corner of Turkey near its borders with Iraq and Syria, environmentalists, human rights organizations, and archaeologists recently won a battle in the effort to avert a cultural tragedy.

Swiss, German, and Austrian firms pulled out of their contract with the Turkish government to build a dam that would flood and destroy a historical ancient city, harm ecosystems downstream, and displace thousands.

To permanently protect this area though, it should be designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Ilisu Dam, a cornerstone in a project to develop Turkey’s electrical and water capacities, is the largest and the most controversial of the 22 dams and 19 power plants scheduled in the $32 billion Southeast Anatolia Project.

At the heart of the controversy is the town of Hasankeyf, carved into the limestone cliffs above the Tigris River. Hasankeyf is reputed to be one of the oldest continuous settlements on earth, at least 10,000 years old, with relics found this summer that may date it to 15,000 years old.

In the Kurdish region of southeastern Anatolia, Hasankeyf has hosted at least nine civilizations, including the Assyrians, the Romans, the Byzantine Empire, the Mongols, and the Ottomans. On a central trading route in ancient Mesopotamia, Hasankeyf boasts more than 4,000 caves; 300 medieval monuments; 83 archaeological sites with ruins, including Hasankeyf Castle, built by the Byzantines in AD 363; and historic tombs and mosques. Its cultural and archaeological value is priceless.

Today the hillsides are dotted with artisans’ stalls, children on donkeys, and caves with restaurants inside.

If the Ilisu hydroelectric dam is constructed as planned 50 miles downstream, much of Hasankeyf – historic caves, ruins, and all – will be buried under 400 feet of water….[cont]

August 30, 2010: On the River: the End of Summer

Boats skimmed along the Potomac River this last weekend of August—power boats, yellow and red kayaks, boxy green canoes, sleek white sculls. I settled into the latter late Sunday afternoon, dropping oars into the warm water. Many in Washington are still out of town—on vacations or home visiting constituencies—but in their place are tourists exploring the nation’s capitol. The heart of the city beats on in festive cadence.

Baking in the summer sun, I eased leisurely down the river—past the Kennedy Center, the Watergate apartments, past the Georgetown waterfront where outside cafes were filled with people eating and bicyclists walking their bikes, past the new park along the river, then under Key Bridge, where a moment of shade brought relief. On the bridge above bikers and runners and cars crossed the river to and from Virginia. My scull sliced the surface of the water past the spires of Georgetown University, which peeked through the trees on the shore like a medieval fortress. I aimed out to the Three Sisters Islands, rowing with one oar to turn the scull then traversed the river, crossing the wakes of larger power boats so I could return on the opposite side, rowing past the nature preserve of Roosevelt Island towards the public boat house.

By the time I neared the home shore, sweat was dripping down my brow into my eyes, blurring my vision. The sun was slowly sinking in the sky, but relinquishing none of its heat. The boat house was already closing, and kayaks and canoes were pulled up on the dock; mine was one of the last sculls to return.

Summer is near its end. On Labor Day next weekend American flags will flutter beside the Potomac, and the political season with midterm elections will shift into high gear. But before the business of campaigns and politicians fill the air, summer may yet linger for just a bit longer like a temporary denouement before the pace of life accelerates. I take a moment here to savor the summer, which has been spent almost entirely in Washington—one of the hottest summers on record—a summer of writing, reading good books and welcoming into life a new grandchild. It has been a summer of quiet pleasures and great moments.

August 27, 2011: Before the Earthquake and Hurricane: Summer Music in the Afternoon

The air is surprisingly cool for late August. I’m sitting on an upstairs porch looking out over the tops of trees in their full dress of summer greens—maples, magnolias, dogwoods with white blossoms. The branches and leaves sway and rustle in the breeze. Somewhere a wind chime answers the moving air with a light ting and ringing like a message in the near distance, signaling the change of seasons. Overhead, shifting faces of white clouds drift through a blue sky, sliced by faint streaks from the trail of a jet that has long since passed by.

In this moment before evening, before the shift in seasons and the rush of autumn, I can almost hear the earth singing. Harmonizing with the wind chimes are thousands of crickets exploding with sound then quieting and birds sweeping through the sky calling to each other. The rustle of the trees, the call of the birds, the chirping of the crickets, the swoosh of the breeze are like nature’s symphony–an unexpected summer moment on this quiet August afternoon.

I sit high enough off the ground to see the sunlight golden on the tree tops and also to see the trees dark green, almost black, where the sun has left and the afternoon shadows have spread. I look down on the roses in a neighbor’s garden and look out on the brick chimneys of other neighbors’ houses.

I’m aware of the different voices of nature around me, each communicating its renditions of life, none of them taking notice of who will run for President of the United States, or who will emerge in power in Libya and Syria, or how the markets will close.

A flock of birds suddenly swoops past talking loudly to each other. What do they see and say and know?

[This post was written late afternoon Aug. 22. At 1:50pm on Aug. 23 Washington, DC shook as a result of an unusual 5.9 earthquake. As I edit this, we await the arrival of Hurricane Irene, characterized as a once-in-a-lifetime hurricane. The locusts, we hope, will pass us by.]

August 30, 2012: Diplomacy on a Summer Evening

It is a sultry evening at the end of summer in Washington, a backyard party on a patio with picnic tables on the deck, red Christmas lights strung across the porch and the night filled with animated conversation among ten Pakistani journalists and their American friends and hosts.

The journalists are soon returning to Lahore, Karachi, Balochistan, Islamabad and other cities and provinces in Pakistan. For the last month they have been working in newsrooms across America. Most are here for the first time, witnessing and learning about American culture and sharing their own culture and experience. They have worked from Tallahassee to Tucson to Los Angeles, from Washington, DC and Baltimore to Providence and Pittsburg; one journalist reported from Minnesota. They have covered American elections, crime, state politics, the judiciary, education and economics.

The Pakistani journalists have also met with the communities, including addressing hundreds of members of the Rotary Club in Tallahassee and having a one on one discussion with a Catholic bishop about abortion.

In their month they all agreed their misperceptions of America were changed.

–I thought Americans would be rude, said one and others agreed that that was their preconception. Instead they were friendly and helpful everywhere.

–They were very friendly, said another, but in Minnesota, they had little knowledge of Pakistan and held some myths.

–When people think of Pakistan here, they think only of terrorism. That was the general misperception.

–I saw how hard Americans worked. I always thought Pakistani journalists were energetic, but an American newsroom—that is energetic!

–I lived with the executive editor, and we were in the newsroom by 7am.

–I was impressed by the huge facilities in American newsrooms. The journalists are very professional. But I come away very proud of my fellow Pakistani journalists who work in much worse conditions.

–I was surprised that 50% of the staff was women. I even had a woman driving me.

The International Center for Journalists will bring 160 Pakistani journalists to work and live in the United States, and has sponsored American journalists into Pakistani newsrooms.

As we shared chicken tandori and lamb sausages and curries and rice in the fading summer light, the guests all agreed that this type of professional exchange opened and advanced relations between people in a way that politicians can’t or don’t.

–I covered the Governor and State legislature, said one reporter. The Governor was lobbying for his bills, especially to get his bill passed on gambling. It was just like Pakistan!

August 21, 2013: Peacocks and Politics

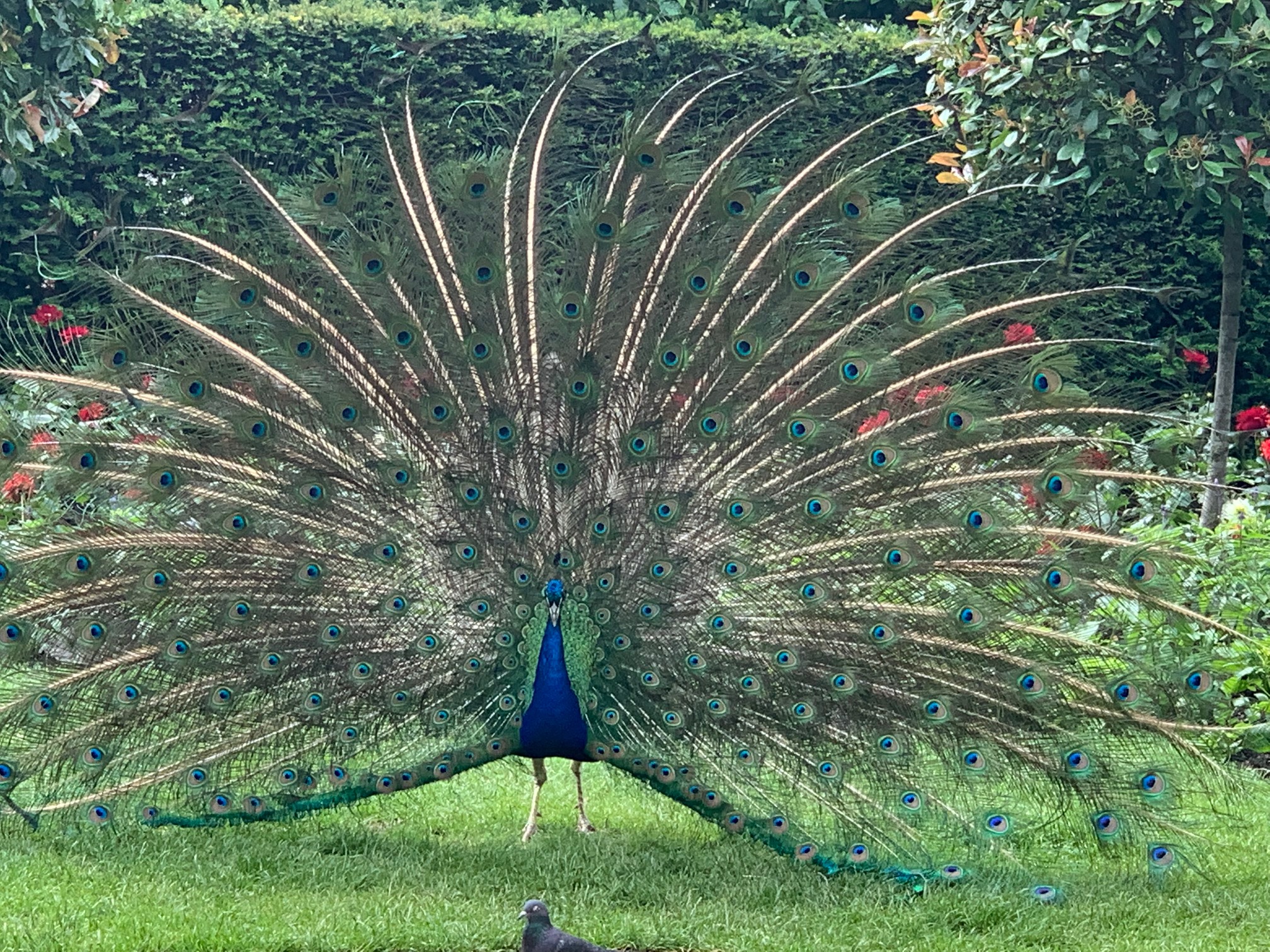

I’ve spent much of the summer on the Eastern shore of Maryland on a river, writing and listening to the quiet lapping of the water against the stones of the river bank, except when jet skis whish by and when the peacocks next door caw and caw at the neighbor’s farm. The peacocks call to each other all day long, broken by a rooster’s cock-a-doodle-do…actually the rooster is yodeling now, though I don’t know what he’s heralding in the middle of the afternoon.

The peacocks wander over from time to time, running across our yard like stealthy children hiding from their parents. I don’t know what prompts their visits. They usually leave a mess, but their brilliant feathers swishing by always surprise and astonish me.

Today as I was moving to a table outside to write this blog, I discovered one of the females nesting, hidden in a bush outside the house and, I believe, hatching a brood of eggs. I don’t know when she arrived, but she lay there motionless as though she had gone into a deep sleep, moving not at all as she protected her eggs. I’m not sure how long gestation is for peacocks, but soon we will be host to baby peacocks! Since the birds wander from farm to farm, no one claims ownership, certainly not me, but suddenly I feel a responsibility, for exactly what, I can’t say, at least a responsibility to give the mother the peace and quiet she has sought by escaping here, away from the other peacocks and roosters. Occasionally we have a dog visit on the weekend so my first responsibility is to make sure the dog doesn’t find the peacock….[cont]

August 2, 2014: Poets, Pardons and Ramadan

(This piece appears on GlobalPost.)

Eid—the end of Ramadan—has come and gone. Traditional pardons have been handed out. In Qatar, poet Mohammed al Ajami (Al-Dheeb), was not among them. He continues to live in a prison in the desert, serving a 15-year sentence for two poems, one praising the Arab Spring and the other critical of the Emir. He (and his poems) “encouraged an attempt to overthrow the regime,” according to the charges.

The over 70 pardons granted in Qatar are reported to have gone to Asian workers charged with theft, rape, drug abuse, bribery, prostitution, etc. These workers will now likely be deported. If Mohammed al Ajami were released, he would also likely leave the country to reunite with his family and then perhaps accept a brief fellowship offered as a poet at a major university.

Throughout the Muslim world Ramadan is a time when dispensations are handed out— as many as 1000 prisoners reportedly released in Saudi Arabia, 800 plus in Dubai, over 350 in Egypt— to individuals charged with violent and nonviolent crimes. But the amnesties were not given to writers, not to poet al Ajami, not to Egyptian journalists or Iranian bloggers. The offense of words and ideas are perhaps judged more dangerous.

Writers in prison in the Middle East who did not get pardons include: Bahrain (3writers), Egypt (5 writers), Iran (35 writers), Qatar (1 writer), Saudi Arabia (2 writers), Syria (11 writers), Tunisia (1 writer), United Arab Emirates (2 writers). *

August 27, 2015: “What to Read Now: War Narratives”

From the September/October 2015 issue of World Literature Today

While the US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been going on for fourteen years, much of American literature from these conflicts is only now emerging. I appreciate the veterans who’ve woven the simultaneously “worst and best days of their lives” into literature. They have turned to all forms to find their truth—poetry, short stories, memoir and the novel. (Disclosure: I’m the mother of a Marine who served in both conflicts and is now one of the novelists listed here.)

I have framed these suggested readings with a history from the Great War a hundred years ago and with a diary of one of the long-serving detainees in Guantánamo. Truth in literature is determined in part by point of view. In these books, the reader can take a journey from many perspectives.

Margaret MacMillan

The War That Ended Peace

Random House

In this nonfiction book, Margaret MacMillan narrates history through the lives of those responsible for World War I. The characters and cousins could populate a fiction collection with their dramas, imaginations and absurdities. MacMillan offers an inside view, revealing the people and stories behind the politics and events that led to a war many feel—and felt at the time—shouldn’t have happened.

Brian Turner

My Life as a Foreign Country: A Memoir

W.W. Norton

The author writes of his deployment as an Army sergeant, beginning in the US learning to identify body parts, watching combat on television, and then arriving in Iraq and facing real combat in the first Stryker brigade. “We rode on a war elephant made of steel,” he writes of the nineteen-ton tank. A poet (Here, Bullet), Turner narrates his experiences and his return home in a poet’s language, which spins the harshest circumstances—the soggy, trodden straw—into gold and art.

Phil Klay

Redeployment

Penguin Press

A veteran of the US Marine Corps assembles a dozen short stories and first person narrators—soldiers on the front lines, in the rear, at desks, with their family, friends, wives and girlfriends back home. The narrators’ voices are witty, unflinching, nostalgic, and the stories make the reader laugh, cry and wonder how a generation honed on this conflict will return to life as it was.

Elliot Ackerman

Green on Blue

Scribner

This novel narrates the war in Afghanistan from the point of view of an Afghan orphan who gets caught up on the American side of the conflict in order to keep his brother alive. He quickly learns that the war has too many sides and so many points of view that truth shimmers only in the eyes of the beholder.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Larry Siems, ed.)

Guantánamo Diary

Little Brown

Guantánamo Diary tells the story of the “war on terror” from the point of view of one who has been detained, tortured, and continues to proclaim his innocence. With a literary and humane voice, Slahi, edited beautifully by Siems and redacted by a censor, renders the horror and humanity in this war that will not end.

August 11, 2016: Sounds of Summer

(This is not a poem)

August on the Eastern shore

Quiet on the river

Birds chirruping in the trees

Crickets—or are they cicadas—clicking in the afternoon, clicking that will build to a crescendo in the evening

CaCaCa of peacocks next door

Water trickling, flowing slowly out to the bay

A power boat whishing by, heading to the open water

A leaf blower, a lawn mower in the distance, jarring the quiet

Leaves rustling in the breeze