Posts Tagged ‘African Writers Abroad PEN’

PEN Journey 36: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part One

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

In pulling out papers from 2005 of PEN conferences and the 71st World Congress, I came across two documents that told a very human story in PEN and a coincidence of life that I share here:

71st PEN World Congress 2005, Bled, Slovenia, Round Table Papers

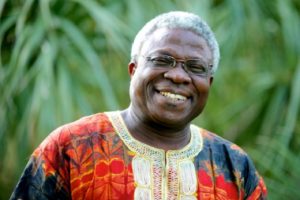

The first paper I skimmed was a talk I’d given as PEN International Secretary at the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee Conference in Ohrid, Macedonia in September 2005; the paper included the testimony of a PEN member at the end. The second text I read was from the Round Table Papers of the PEN Congress a few months before, in June 2005. This paper was on the Congress theme Tower of Babel: Blessing or a Curse? The paper was the first in that publication and was written by celebrated Nigerian poet Niyi Osundare who speculated on what the world would be should there be just one language and then meditated on what in fact the world was. Shared below are excerpts from Dr. Osundare’s paper, “The Blight and Blessing of Babel:”

“A one-language world would be too simple, too linguistically neat, too unrealistic. And, I daresay, too unnatural. For everywhere in nature there is a tendency towards fission and mutation on an intra-and inter-generic basis. Variety is not only the sauce of life; it is also its source…

Nigerian poet Dr. Niyi Osundare

“Yoruba culture (the culture in which I was born and raised, and one that I know best) understands the necessity of diversity and inevitability of varieties in different aspects of human life. Hence the saying “Mee l’Oluwa wi” (Many, says the Lord) and “Ona kan o w’oja” (There are countless routes to the same market), both of them short, handy variations on a longer proverb “Oju orun t/egberun eye fo lai farakanra (The sky is wide enough for a thousand birds to fly without colliding). Corroborating this pluralist perspective is the folktale about the Tortoise, ever cunning and self-centered, who one day decided to capture all the wisdom in the world and seal it up in one pot for his own use in an effort to become the wisest being in the world. Of course, his project ended up in a laughable disaster as his pot fell to the ground and exploded while different fragments of the imprisoned wisdom dispersed in different directions, free for all, unmonopolisable. In an essentially pluralist Yoruba worldview, phenomena exist by mutual definition; a thing, a person loses its sense of proportion when there is nothing else to compare it with. The trajectory of life hardly ever follows one straight and narrow path; it must confront the crossroads, experience the thrills and tortures of decision and indecision, before arriving at the juncture of choice. And for the act of choosing to take place, there must be more than one…

“Literature (and the arts generally) is, no doubt, a powerful weapon in the struggle against the blight of Babel. By endowing our airy thought with that ‘little habitation’ and ‘name’ (hail Shakespeare, one of the supreme healers of the wounds of Babel), by generating universal sympathies, globalizing the particular and particularizing the global, by producing that music of the spheres whose winds stir the eaves in different lands, by evoking images which touch hearts across cultures, by articulating those humane values that are essential to human freedom everywhere in the world, by constantly lifting the human spirit and enriching, interrogating human reality with the supple possibilities of fiction…literature strives to restore some of the lost potentialities of Babel. For every significant writer is a bridge-builder of a kind, a witness, a participant-observer, an advocate of a truly humane future.

“No doubt, the phenomenon of Babel has left its fragmentations and dispersals. But it has also bequeathed to humanity a panoply of sounds and letters, an astounding (even if confounding) array of tongues which challenges the tyranny of uniformity and monotony of methods. It has necessitated the building of bridges across diverse tongues and cultures, these bridges being, in a way, a horizontal alternative and antidote to the vertical impossibility of the Tower itself.”

L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary) and Kata Kulavkova (Chair PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

Dr. Niyi Osundare, a Nigerian PEN member, had moved to New Orleans for specialized education for one of his daughters and was also a member of the African Writers Abroad PEN Center. Recounted here is my talk to the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee a few months after the Bled Congress, in September 2005. Only as I recently read the end of my paper did I grasp the connections and the range of PEN’s reach and work. My observations at the time:

The theme of the 8th Ohrid P.E.N. Conference—Writer Within and Without a Homeland—struck a particularly sonorous chord as I was preparing to come here.

In the U.S. the question of homeland has been on the national consciousness for the past month as one of America’s most diverse and multi-lingual cities—New Orleans—has literally disappeared. Its population evacuated as the city sank into the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. A large portion of the Gulf coast also fled in the face of Hurricane Katrina. Over a million people dispersed throughout the land in one of the largest displacements in the nation’s history. Many will never return to their homes.

In Europe and Africa, Asia and Latin America even larger displacements have occurred in the last century, often because of war, famine, politics, and also weather. All of us remember the disappearance of towns and villages and whole sections of coasts in the countries hit by the tsunami last December.

When a home is suddenly gone, family scattered, livelihood and career and ambitions all uprooted, one is forced to consider what endures, and what one can take with him. Home moves from a physical place to a place in consciousness.

The ability to speak with others and to tell the story is especially important and makes the idea of language as homeland compelling, also imagination as homeland, literature and art as homeland, and particularly relevant to PEN, a community of fellowship as homeland.

I’d like to read a message to PEN’s Africa Writers Abroad Centre from a Nigerian writer trapped in New Orleans:

This is my first real internet access since the disaster struck…I can’t thank you enough for your concern and care. It’s been all so overwhelming. My wife and I are alive and, after passing through five horrendous “evacuation centers”, have been allocated to the Red Cross shelter in Birmingham, Alabama. The nightmare of the past seven days is simply unimaginable. We very narrowly escaped drowning in our own house. Pursued by an 8-foot high toxic flood water (15 feet in the street outside our door), we were forced up a stuffy, airless attic, where we were holed up for 26 hours, with no food, no water, no prospect of any rescue. We were only saved by the fortuitous intervention of a neighbor who heard our shout for help when he came round with his rescue boat to pick up something from his own house. With life vests provided by him, we managed to swim out of our house, leaving everything we had behind. Right now, all our clothes, books, academic and professional credentials, travel documents, computers, manuscripts, etc are submerged in the dirty waters of the New Orleans flood. Hell has no other name… We deeply appreciate your concern. Kindly pass on our gratitude to all on your list serve.

Yours in the Eye of the Storm

[Niyi Osundare]

I’m told he has been overwhelmed by the outpouring of concern. While the concern and offers of assistance can’t replace what was lost, it can fill in some of the spaces in the heart.

In the U.S. those displaced are at least relocated in the same country and for the most part speak the same language, though the difference in accents has its challenges. What has been heartening has not been the help of government agencies, but the outpouring of citizens in communities all over the nation and abroad. One would wish this empathy would prevail and continue.

The ability to imagine and to reach out to another and try to see from the other’s point of view is one of the elements of great literature and also of great people. This empathy is a value around which PEN has developed and one which PEN at its best embodies.

A community spread across 99 countries, shaped by different nationalities, cultures, races, religions, and languages, PEN is a fellowship of writers who appreciate the importance of telling a story and defend the writer’s freedom to tell it as he sees it and to tell it in the language of his choosing. Language is the writer’s tool, expressing the music of his thoughts and sounding the chords of his imagination.

Language, imagination and fellowship—all are a kind of homeland that can survive the elements and can even survive politics and war, a homeland, one of whose addresses we like to think is at P.E.N.

Dr. Osundare and I didn’t know each other at the time though perhaps met briefly at the Bled Congress which was attended by more than 275 writers. I know many of his colleagues from Nigerian PEN and at the time from the African Writers Abroad PEN. I made the connection only as I reviewed the papers. Dr. Osundare is now a professor at the University of New Orleans.

Delegates at PEN International World Congress, Bled, Slovenia, June, 2005. L to R: Remi Raj (PEN Nigeria), Dan Kayhana (PEN Uganda), Frankie Asare Donkoh (PEN Ghana), Alfred Msadala (PEN Malawi)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 37: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part Two