Posts Tagged ‘death threats’

PEN Journey 11: Death and Its Threat: the Ultimate Censor

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

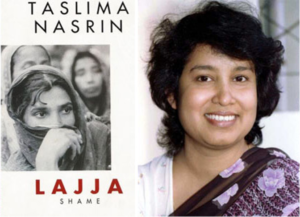

In Bangladesh novelist Taslima Nasrin was in hiding. Death threats had been issued, a price put on her life. On the streets of Dhaka and other cities, crowds threatened to hang her because of her words in a newspaper challenging the Koran and Islamic laws and because of her novel Lajja (Shame) which depicted Muslim atrocities on Hindus after a mosque’s destruction in Ayodhya, India.

The time was summer, 1994. In London Sara Whyatt, PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee Coordinator, and I sat in a Kensington hotel restaurant waiting to meet a man who’d called the office and said he was Taslima’s brother and wanted to talk with us. PEN had been actively working on Taslima’s case for the past year, sending out Rapid Action Alerts, meeting with Bangladeshi government officials in London and in the U.S. and Europe, calling on the government to protect her. The case had gained international attention. Given recent violence around fatwas, including those on Salman Rushdie, we were wary. We didn’t know Taslima had a brother. We spoke with MI5 who advised us to have a spotter for the meeting. We arranged a tell so that if the encounter was not legitimate or we perceived trouble, I would take my sunglasses from the top of my head and set them on the table. The spotter—PEN’s bookkeeper—sat at another table and could quickly summon help. We weren’t certain, but we thought MI5 was also in the hotel.

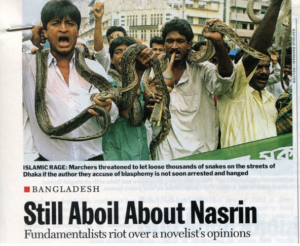

In retrospect the drama around Taslima’s case seems inflated, but during that period of 1993-1994 the situation had escalated to the point that religious leaders were warning that the government would be overthrown if Nasrin was not arrested. In June, 1994 when an arrest warrant was issued, Taslima went into hiding. A nationwide hunt was launched, and snake charmers carrying poisonous snakes marched in Dhaka and warned that thousands of snakes would be let loose if Nasrin was not arrested by June 30.

Time, July 11, 1994. Photo by Rafique Rahman-Reuters

In this atmosphere PEN had received the call from Taslima’s older brother. International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and PEN’s Women’s Committee, in particular its chair Meredith Tax in New York, had been in touch with Taslima and her lawyers, but in the time of faxes, (now fading), inconsistent telephone connections, and no internet between writers, no one had yet confirmed a brother coming through London. This kind of high drama was not PEN’s usual modus operandi. In the years I chaired PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), more than 900 writers threatened, detained, in prison, and killed came across PEN’s desk annually. Approximately a quarter of these were designated main cases which meant PEN had sufficient information to verify the situations and had members to work on the writer’s behalf. However, only a few became global causes like Taslima’s, gathering energy, attention and advocates around the world. This usually happened when the threat of death was credible and immanent and when the circumstances of the writer connected to larger issues.

That day in London, a man in his thirties approached our table. He looked so much like pictures of Taslima that we quickly set aside our suspicions. He worked for an airline and was passing through London. He was able to answer questions and confirm details of the case such as what Taslima had actually said to the newspaper which had misquoted her calling for revision of the Koran. I still have my notes from that meeting. Her brother explained that Taslima had said she wanted to modify Sharia laws, not the Koran. “I want men and women to be equal,” she’d said. She was charged with blasphemy under a law left on the books by the British.

Her brother told us that her lawyer was afraid. The lawyer couldn’t move for bail unless Taslima was present, but if the government didn’t give security for her, they couldn’t take the risk of Taslima coming to court. The government said if Nasrin went to court, anything could happen in court or in jail. In jail she could be killed. Her father’s home had been attacked, and he was now under protection.

Her brother confirmed that Taslima had finally agreed that she needed to leave Bangladesh though she was reluctant. “If I go from Bangladesh, who can write about these poor women?” she asked. And yet she wasn’t able to write anything now, he said, and her life was not safe if she stayed.

Her trial date had been set for Aug. 4. If she didn’t appear, the government would seize her things, including her passport, which they had taken away before but had returned when she resigned her post as a doctor. She was a medical doctor as well as writer.

Her brother’s message to us that day was: “Save my sister!”

Through discussions with her lawyer, with selected PEN members and with the Bangladeshi courts, it was finally arranged that Taslima would turn herself in late in the evening. Bail would be set and met, and in disguise she would leave the court. The president of Swedish PEN flew to Dhaka and accompanied her in a flight to Sweden, where she lived for years in exile.

It was lonely in exile. I met with Taslima in early September 1994, a few weeks after her arrival in Stockholm. I have notes from those meetings. “One day I’ll go back,” she said, “but I don’t know if I could live in my country anymore. I don’t know what will happen. I want to live in Bengal, but they will kill me. I couldn’t take my writing out.”

She explained that she was from a Muslim family with Hindus as her neighbors. “From the beginning I went to their houses, played with them. I know their culture, attitudes. I know their happiness and sorrow from childhood. It is not difficult for me to reach them.” After the violent incidents in Ayodhya, India where Hindu women were raped and their homes looted, she said, “I felt them. I have felt the danger and had to write for them…Why can’t I write a book in reverse, but they feel they should write my book in the case like Lajja…In India, Hindus can’t feel Muslim, and Muslims can’t feel Hindu…In Bengal, Hindu and Muslim live separately…People think men are superior to women. Women always get advice from men. Mothers are always kept quiet. It is not allowed for a mother to give advice to a son.”

London Review of Books, September 8, 1994

At the time and in retrospect at PEN we questioned whether any of our actions escalated the situation for Taslima’s case. This was the Bangladeshi government’s argument, but Amnesty and numerous human rights and freedom of expression organizations also highlighted her situation. Through IFEX, the International Freedom of Expression Exchange of which PEN was a founding member, reports circulated worldwide. The fact was, Taslima Nasrin was in real danger. PEN went into action and helped with her extraction.

In November 1994 Taslima was a special guest at the 61st PEN International Congress in Prague, opened by Vaclav Havel as the keynote speaker. In December that year she received the prestigious Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, given by the European Parliament.

Though Taslima’s case was the most celebrated at the time, there were numbers of other writers and women under threat because of their writing. In a town in Northern Greece Anastasia Karakasidou had received anonymous letters threatening to rape and kill her in front of her children because of her scholarly dissertation on the ethnic Slav population in that region. In Algeria another woman writer stayed in her house afraid even to go out on the street because her words challenged both government and fundamentalists’ violent policies. She had not received a direct death threat, but she was a well-known and recognized writer in a country where more writers had been killed in that past year than in almost any other, including Somalia, Angola and the former Yugoslavia.

Death was the ultimate censor, and the threat of death was its chilling companion. International PEN’s Writers in Prison casebook at the time listed at least 22 countries where writers were under death threats. In four countries the writers had gone into hiding. Death threats also prompted self-censorship for many writers. Most of the threats did not come directly from governments but from individuals who professed to be offended by the writer’s words. The offense, however, was almost always tied to a political or religious position, and the writer’s life became a political, not a moral, consideration.

While issues of communal violence and religious and political Islam differed from the rights of ethnic minorities in Northern Greece or from political probity in Argentina, Guatemala, Peru, Paraguay where PEN listed high numbers of death threats, the common need in all these cases was for the government to protect the writers and take action against those who issued the threats.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 12: Tolerance on the Horizon?