Posts Tagged ‘International Crisis Group’

Democracy in Africa: Who Can Chat with Kabila?

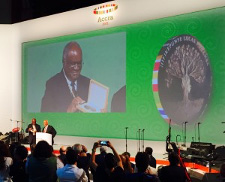

I returned last week from two conferences and a debate back to back in Africa. The Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which has developed an index on good governance and transparency in Africa, gave its annual prize to a former African leader, followed by a day-long discussion on “African Urban Dynamics.”

The Africa Report Debates inaugurated its series with the question: “Democracy vs. Development.”

And the International Crisis Group, an organization dedicated to analyzing and offering policy recommendations for current and potential conflicts worldwide, (and on whose board I serve) gathered its Africa program for an internal analysis.

From the gatherings of eminent African leaders, policy makers, scholars and commentators I took away the following contradictions across the continent:

–There is an expanding and active civil society at the same time there are spreading and virulent extremists and criminal networks.

–There are growing numbers of working democracies at the same time entrenched leaders are trying to change constitutions to hold onto power in single-party states.

–There is developing urbanization offering services and employment for citizens while slums and marginalized communities expand.

The debate “Democracy vs. Development” concluded overwhelmingly that the two must go hand in hand.

“Fast and equitable development and diversity come through democracy,” according to Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Ethiopia. But he added, “Democracy is a process. It matures over time and grows from the inside. It can’t be prescribed. It needs institutions and education. We don’t need paternalistic intervention.”

Ethiopia was pointed to throughout as making significant economic progress. But in a break between panels, I asked Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus about the restrictions on freedom of expression in Ethiopia and the number of writers and journalists now in prison there. His answer: “They broke the law.” Their imprisonments have been challenged by major freedom of expression organizations like PEN International, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty, Committee to Protect Journalists, as well as by African PEN centers, I pointed out; this is not a positive sign for healthy government. He and I did not resolve the question between us.

Good news and reasons for hope on the continent include the peaceful elections and transfer of power this year in Nigeria, which has a strong and vocal civil society even as it struggles with the radical extremism of Boko Haram in the North and with criminal trafficking. Also positive is the immanent transfer of power through elections in Burkina Faso, where citizens rose up peacefully last year and opposed the extended 27-year rule of its leader, demonstrating a strengthening civil society. Ghana, where the conferences convened, held peaceful Parliamentary elections while we were there.

“We need heroes,” said Mo Ibrahim, who initiated the conference and the award which was given to the former President of Namibia. Hifikepunye Pohamba won the $5 million prize for “forging national cohesion and reconciliation at a key stage of Namibia’s consolidation of democracy and social and economic development.”

“We must reject the manipulation of the Constitutions,” said former President Pohamba in his acceptance speech. “No individual or group of people should be allowed to abuse power from democratically elected leaders with impunity.”

Electoral transitions in East, West and Southern Africa could unhinge or advance their regions, including in Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Cameroon, Uganda and Zimbabwe. In many of these countries, the current presidents are hoping to hold onto power past constitutional limits which they are trying to alter or past public tolerance. Outcomes of these elections will be important indicators to watch.

Informal conversation outside the symposiums:

“Who can chat with Kabila?” (President of DRC). “I understand he’s scared. His father was killed here.”

“Who can offer him immunity?”

“Can he have a soft exit?”

“Will he exit?”

“I don’t think so.”

Behind all the statistics and the headlines, the story after all is always about people.

Clouds Over the Bosporus

It rained every day on the Bosporus as we ferried back and forth across Istanbul’s grand waterway to discuss current and impending conflicts in the globe. Inside the windowless room, sitting in a large square facing each other, former presidents, prime ministers, foreign ministers, ambassadors and a former NATO commander toured the world in words and debate to find paths to end these conflicts, to encourage the opening up of political systems and to keep those systems, their leaders and others from killing their citizens. Reports from seasoned, on-the-ground researchers informed the discussion of the board of the International Crisis Group.

Outside the meeting room, the Middle East continued in a state of foment. Its citizens had taken by surprise many of the experts in the room. Egypt’s and Tunisia’s regimes had fallen through nonviolent resistance comprised of strikes and mass protests by its citizens. However, Libya’s President Gaddafi was attacking and threatening to slaughter his dissenting citizens and had sent that country into civil war. Syria and Bahrain, slightly more restrained, had also killed hundreds of protesting citizenry.

The doctrine of the Responsibility to Protect was a focus of the debate. At what point does the international community have a responsibility to intervene when a government not only doesn’t protect its citizens but attacks them? Can the international community prevent such actions so that there will never again be another Rwanda or Srebrenica? Does the responsibility to protect inevitably lead to military intervention as it has in Libya? How does the U.N. and NATO unwind its commitment? Can it? Should it? And what about the simultaneous bloodshed in the Ivory Coast? Why were nations not invoking the Responsibility to Protect there?

These questions unfurled and swirled with no definitive answers. Rather, the answers were iterative, inching towards solutions. Even with some of the brightest minds around the table, foreign policy and diplomacy is not so much an art or a science; it is more like a grand bazaar, a trading of perceptions and perceptions of national interests.

In the forums on the Bosporus I was able to offer only a small window on civil society, on citizens who do not sit at such tables but have been willing to go to jail and even die because they have written or spoken their protests for freedom. I was more of a deputy sheriff in the gathering, without a global answer but with a reminder not to forget to open the stable door if the barn was being set on fire.

The freedom to tolerate without imprisoning or killing and the freedom to be tolerated without constraint is a rare and essentially modern concept in the world. When thousands, then hundreds of thousands, then millions rise up insisting on this freedom, it is a fearsome and transformative sight. Freedom itself is a concept still developing. Is there a point when my freedom depends on your captivity?

No easy answers, but I hope you’ll share your thoughts in the comment forum below.