Posts Tagged ‘United Nations’

PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I first visited Berlin in the fall of 1990 just after Germany reunited. I was living in London and took my sons, ages 10 and 12, to witness history in the making. I returned on a number of occasions, researching scenes for a book, attending meetings, and visiting German PEN in preparation for PEN’s 2006 Congress. Each time Berlin’s face was altered as the municipalities east and west moved to become one city again.

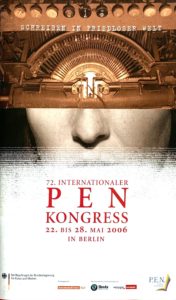

PEN International’s 72nd World Congress, Berlin, 2006

At the time of PEN’s Congress in May 2006, Berlin was bedecked with water pipes above ground—pink, green, blue, red—before the city buried its plumbing and infrastructure beneath the streets. Portions of the city had the appearance of an amusement park; there were also sections of the Berlin Wall with its colorful graffiti still standing, more as art exhibit than stark barrier to freedom.

“Welcome to a United Berlin” the German PEN President headlined his letter to the 450 delegates and participants for PEN’s 72nd World Congress. The Congress theme “Writing in a World Without Peace” was challenged by the reunification of Berlin and Germany, a historic event which bode well for the prospects of peace and which stood in contrast to the history that had come before. Yet the globe was still in conflict in the Middle East, in Asia and in Latin America where writers were under threat.

“There are countries such as Iran, Turkey or Cuba, where authors are jailed because of their books,” noted International PEN President Jiří Gruša. Resolutions at the Congress addressed the situations for writers imprisoned or killed in China, Cuba, Iran, Mexico, Russia/Chechnya, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, and other countries.

Left: Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) meeting at Berlin Congress. Karin Clark (Chair WiPC) and Sara Whyatt (WiPC Program Director). Right: WiPC Conference in Istanbul: Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN/PEN Board), Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Jonathan Heawood (English PEN), Notetaker

Two months before in March, over 60 writers from 27 PEN centers in 23 countries had gathered for International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul where the WiPC planned a campaign against insult and criminal defamation laws under which writers and journalists were imprisoned worldwide. The conference also addressed the recent uproar over the Danish cartoons, impunity and the role of internet service providers offering information on writers, especially in China. A working group formed to support the Russian PEN Center which was under pressure from the Russian government.

Berlin, however, was sparkling and filled with the energy of reunification. “Today, this city—once separated by a Wall most drastically manifesting the division of Germany and Europe—has not only been re-established as the capital of Germany, but has simultaneously turned into a thriving meeting-place between East and West and North and South,” welcomed Johano Strasser, German PEN President. “Here in Berlin, history in all its facets—from the great achievements of German artists, philosophers and scientists to the crimes of the Nazis—has left its mark on the urban landscape.”

Left: German Chancellor Angela Merkel addressing PEN members at 72nd PEN Congress, 2006; Right: PEN International President Jiří Gruša speaking to PEN delegates and members at the Federal Chancellery; front row: German PEN President Johano Strasser, Chancellor Angela Merkel and PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman. [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

The keynote address by Nobel laureate Günter Grass challenged the conflicts around the globe and the countries engaged in them. “There has always been war. And even peace agreements, intentionally or unintentionally, contained the germs of future wars, whether the treaty was concluded in Münster in Westphalia, or in Versailles,” he said.

Nobel laureate Günter Grass addressing Opening Ceremony of PEN International’s 72nd World Congress in Berlin, 2006 [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

As I sat on the dais on the edge of the stage listening to this renowned German writer, I leaned over to Jiří and said, If there is a standing ovation, I can’t stand. I was concerned. Grass could say and think whatever he wanted, but PEN was a non-political organization. Whatever my views of my country’s foreign policy, I was an American; I was also the mother of a son in uniform. Jiří leaned back to me and said in effect: Don’t worry, I won’t stand either. The speech ended with applause but no ovation, and then everyone got up and went to the next event.

It wasn’t my role to argue with Günter Grass even had the occasion allowed. But it was important that PEN assure the open space for debate existed which it did later in the Congress workshops and programs. PEN was filled with a multitude of points of view among its members; it did not have a litmus test of politics, only a commitment to the free expression of ideas. It offered a wide tent where views could be debated and challenged. Dogmatic political certainties often fell on their own in the alchemy of literature and imagination.

PEN members and delegates from around the world at Opening Ceremony of 2006 PEN Congress [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

Programs at the Congress also featured Nobel laureate and PEN International Vice President Nadine Gordimer and writers from around the world, including former International PEN Presidents Ronald Harwood, and György Konrád, Bei Dao, A.L. Kennedy, Margriet de Moor, Péter Nádas, Per Olov Enquist, Mahmoud Darwish, Duo Duo, Jean Rouaud, Johano Strasser, Veronique Tadio, Patrice Nganang and others. These writers participated in the literary events, including an evening of African literature and one of writers of German literature who had immigrated from abroad to Germany or had non-German cultural backgrounds. Afternoon literary sessions included prominent PEN writers introducing authors of their choice, an afternoon of essays and discussions on the theme Writing in a World without Peace and a lyric poetry afternoon.

PEN’s 85th anniversary coincided with the 60th anniversary of the United Nations. Both organizations had been founded after a World War out of an idealism that arose from desperate times with the hope that the future could be better than what had just transpired. “Both organizations were founded on a belief in dialogue and an exchange of ideas across national borders,” I noted in my address to the Assembly of Delegates. “When U.N. members were writing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the framers consulted, among other documents, PEN’s Charter.”

PEN also had a history with the city of Berlin, where PEN members had gathered in 1926 for the first international meeting of importance held in Berlin after World War I. At that Berlin Congress tensions had arisen among old and young writers, writers from the west and the east, and debate had flared about the political versus the nonpolitical nature of PEN. The debate that stirred in Berlin in part led to the framing of PEN’s Charter the following year.

Since those early days, PEN had grown in size beyond what the founding writers might ever have imagined. After the 2006 Berlin Congress, with the addition of centers in Jamaica, Uruguay, and Pretoria, South Africa, PEN had 144 centers in 101 countries in almost every time zone. The PEN world didn’t sleep. Someone, somewhere was always awake doing something. Through its centers PEN International participated in at least a dozen conferences around the world each year, including meetings of its standing committees. PEN thought globally but worked locally.

Berlin—with its own alterations and progress—proved a fitting location for the presentation of International PEN’s new Three-Year Plan. For the past decade, since the 75th Anniversary at the Congress in Guadalajara, PEN International had been in an organizational reformation. It now had a governing structure with a global Board that participated in decision-making; it had revised its Constitution and Rules and Regulations; it had developed a budget, increased its funding, and recently moved its offices into Central London to a larger space with cheaper pro rata rent and an elevator, which had meaning for anyone who had climbed the steep four (or five?) flights to PEN’s old offices. The staff size had also increased, and PEN had hired its first Executive Director, Caroline McCormick Whitaker, former Development Director from the British National History Museum.

International PEN Board meeting preceding 72nd PEN Congress in Berlin, May 2006. L to R: Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Kata Kulakova (Chair Translation & Linguistic Rights Committee), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Chip Rolley (Chair Search Committee), Karen Efford (Program Officer), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International PEN President), Peter Firkin (standing—Centers Coordinator), Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Jane Spender (Programs Director), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair)

Because British charitable tax law had changed, the opportunity had also arisen to unite International PEN and the International PEN Foundation into one charitable organization: International PEN, Ltd, a step that would provide the legal framework and protection for the organization and PEN’s name, would limit personal financial liability of the Board and attract a wider funding base. At the Berlin Congress, resolutions and approval were endorsed for this step which would be finalized the following year at the 2007 Congress in Dakar.

Caroline Whitaker took the Assembly of Delegates through the Three-Year Plan which had been developed after widespread consultation with PEN centers and the Board. She acknowledged that PEN couldn’t do everything that everyone wanted right away, that it was necessary to focus resources even as PEN developed more resources.

The Plan, which had grown out of all the discussions and preceding plans, concentrated on PEN’s three missions: to promote literature, to protect freedom of expression and to build a community of writers. “International PEN will work regionally to connect the activity of its many Centers around the globe on these issues,” Caroline told the delegates.

All PEN’s Standing Committees met at Berlin Congress—Writers in Prison Committee, Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, Women Writers Committee and Peace Committee [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

In helping to develop PEN’s centers, the Three-Year Plan recommended International PEN focus on one region at a time, beginning with Africa where the 2007 PEN Congress would be held. International PEN would assist in programming and fundraising for development of PEN’s African Centers. The next regional focus would be Latin America, where PEN’s 2008 Congress was to be held. This rolling focus would allow the limited international staff to plan strategically. Regular daily work would still continue for the needs of centers in all regions.

PEN members met in workshops at 72nd Berlin Congress. Topics: PEN in the World—Global Issues; Education; the Strategic Plan; Centers; Networks and Partners; Asia and Central Asia; Middle East; Africa; Europe and Americas [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

As International PEN’s work had taken me across the globe that year, I’d come to see that PEN and its members formed a kind of intricate net which helped hold civil society together, the kind of sturdy net used on hills to prevent landslides. In a way that is what PEN members did around the world. They helped prevent literary culture and languages and freedom of expression from slipping away by both their active programming and their defensive actions

At the 1926 PEN Congress in Berlin International PEN’s President John Galsworthy and PEN’s founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott had their voices recorded and preserved in a project of the German state. Galsworthy read a page from his Forsyte Saga. According to Dawson Scott’s journal, she recorded the following: “Even as individuals become families and families become communities and communities become nations, so eventually must the nations draw together in peace.”

It was a worthy, if not yet realized goal, but at least in PEN we had a global family.

Mayor’s reception for PEN members and participants at 72nd World Congress in Berlin, May 2006 [Photo Credit: Tran Vu]

Elections at 2006 Congress:

International PEN President: Jiří Gruša was re-elected for further 3-year term.

International PEN Board: Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian Center) and Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN re-elected to the Board)

Vice Presidents: Toni Morrison (American PEN) and J.M. Coetzee (Sydney PEN) elected Vice Presidents for service to literature and Gloria Guardia (Panamanian Center) for service to PEN

Women Writers Committee: Judith Buckrich (Melbourne Center) re-elected as Chair

Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee: Carles Torner (Catalan PEN) stood down as Vice Chair, replaced by Josep Maria Terricabras (Catalan PEN)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 42: From Copenhagen to Dakar to Guadalajara and in Between

Chatham House Rule and Other Civilities

Last week I participated in a number of forums operating under the Chatham House Rule—a large dinner in Washington with experts on Afghanistan, another in New York focused on the United Nations, panel discussions on North Korea, Myanmar, Ukraine and Iraq and a full day meeting focused on troubled spots around the globe attended by former prime ministers, foreign ministers, ex-military officials and experts.

What struck me in this compressed tour of world conflicts was the civility and richness of the discussions which wrestled with problem-solving compared to the public discourse these days that sometimes seems reminiscent of a high school lunchroom.

In a meeting held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use information, but the identity and affiliation of the speakers are confidential. The purpose of the rule, first established in 1927 at Chatham House: The Royal Institute of International Affairs in London, is to encourage openness and the sharing of information. Anonymity is not to encourage personal gossip and rumor.

No problems were solved in last week’s meetings, but analysis from multiple points of view, which were not always in agreement, were debated and iterated. Issues, not personalities held the focus. To the extent personalities framed the problem, steps towards engagement or containment were set on the table.

Throughout the discussions, I recalled Albert Einstein’s counsel: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking that created them.” It is a challenge to think outside traditional corridors of thought and even more challenging when respect for ideas is subsumed by attacks on people.

Many of today’s conflicts spring at least in part from the politics of identity—be that identity defined by religion, political party, gender, race or nationality. The aggregating principal of nations appears to be fragmenting in many areas of the world with authority breaking down or hardening into authoritarianism.

There never have been easy solutions for mankind living together, but the Chatham House Rule offers at least a momentary space for ideas to cross borders and barriers before being shot down.

The Last Colony?

The desert stretched out like a beige patterned quilt as far as the eye could see. The pattern looked like birds’ wings or boomerangs in the sand as the plane descended, then the swirls of sand resolved into rocky ground. In the distance a few concrete buildings rose around the pink watch tower of the airport as I landed in Laayoune in the Western Sahara.

A 103,000 sq mi stretch of desert and coastline twice the size of England, larger than all of Great Britain, the Western Sahara is called by some “the last colony.” Extending south between Morocco and Mauritania with almost 700 miles of coast edging the desert, the region has been in a political quagmire for the last four decades. Spain and Mauritania renounced their claim to the area in the late 1970’s, leaving only Morocco and the indigenous Sahrawi’s in dispute.

In February, 1976 the Sahrawis declared a sovereign state, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). For almost 16 years (1975-1991) Moroccan forces and the Sahrawi indigenous Polisario Front engaged in armed struggle. For the next 22 years the United Nations has overseen a political limbo. A referendum on independence was promised but has been stalled year after year.

I first became interested in the Western Sahara in the early 1990’s when chairing PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. The stories of torture and the conditions in the prisons of the Western Sahara were as grim as any I encountered. Many died and never made it out of the prisons, which were run by the Moroccan security forces. There were also bleak reports from prisons run by the Polisario rebels. I still remember stories of writers who took their bar of soap they were given each month and wrote poems on their trousers. The writers then memorized each other’s poems as a way of staying sane. They also scoured the prison yard in the one hour they were given each day and found scraps of paper and used coffee grounds to write their forbidden verses. Their stories demonstrated how one endured—through fellowship and a flight to the imagination.

Since that time the armed conflict has officially ceased; Morocco has granted amnesties, and most of the prisons have allegedly been closed, but there are still reports of “black jails” with grim conditions even in the capital. There are large areas where no one is allowed to visit.

My visit was brief, the visit of a tourist. I hired a taxi recommended by the small parador where I stayed, the hotel itself recommended by a friend of a friend who worked at the U.N. My driver spoke Spanish and Arabic, some French and little English. I speak English, some French, less Spanish and very limited Arabic, but we managed. I asked him to show me around the city then take me into the desert and then to the beach.

Those living in Laayoune are living their regular lives, women in long djellabas with head scarves, children going to school—you can hear their chatter and laughter on the streets—men also in djellabas or slacks selling in the shops and markets. But the area is a high security zone. The U.N. and the Moroccan security are present, and travel is restricted. No one is allowed too far east where a giant man-made sand berm separates the Moroccan-dominated region from the smaller Saharwi Polisario region near Algeria. Land mines are said to be scattered throughout the no man’s land in between.

In my 24 hours in the capital Laayoune, a city of around 200,000 with 70% of the Western Sahara’s population, I was stopped at six checkpoints. Two were on the way to the desert where a two-lane road stretched through the sand and rock. Any other journey in this area would need to be made with an off road vehicle or on a camel, but I saw only a few camels.

At one point on the way from the desert to the beach, I was delayed for 45 minutes with my passport examined twice. Everyone was friendly; I was friendly. A policeman with a moustache wearing a crisp blue uniform with white belt and military hat, looking very French (though the larger influence in the Western Sahara is Spanish), stood in the middle of the highway to stop us then came over to the taxi.

“Bonjour,” he smiled at me. “Bonjour,” I replied. “Passport?” he asked. I handed him my American passport. My driver had already called another policeman whom we waited for at a designated place in the city to get permission to go to the beach. At the beach are the fish processing plants and a phosphate plant as well as a promenade and beach and the Atlantic. We were given permission so I’m not sure why we are being stopped.

“Profession?” he asked. “Ecrivan,” I answered. “Journaliste?” he asked with suspicion. “No…ecrivan…romans.” I smiled. He smiled. He took my passport and went back to his car where he and the driver conferred for fifteen minutes. I watched them in the side mirror and wondered if I should get out of the car but decided I should stay inside. He returned to the car and gave me back my passport. He smiled I smiled. But still he didn’t let us go.

Meanwhile cars and a few trucks passed by without being stopped. They were driving south either towards the beach or all the way down the highway to Mauritania, over 600 miles away. I’ve been told this is a smugglers’ route. I wondered what traffic might have passed while I was being checked.

The driver returned and asked for my passport again. Another 15 minutes went by. I continued to watch them in the rearview mirror. Finally I got out of the car. I didn’t walk towards them. I just stood leaning against the taxi in the wind—a lone American woman traveling in the desert, sitting in the front seat of the taxi because it gave me a better view. I was probably not a sight they were used to. After almost 45 minutes, we were finally released. I don’t know what the conversations were. The driver told me it was about his license plate; one of its numbers was wrong; he was given a fine. Then why did they need my passport…twice, I asked. But he had no answer I could understand. Instead he took me to lunch at a restaurant on the beach, which I thought was either his father’s or his father worked at, then he invited me to his home, where he told me his mother had made me tea. His mother didn’t appear, but a tea service was set up, and he served me the delicious sweet mint tea in an elaborate Moroccan tea ceremony. When I paid him at the end of the day, I tipped him enough to pay the fine though I didn’t really know what happened, but we were smiling.

At the hotel, the U.N. representative who is a friend of a friend picked me up to go to the airport. Coincidently he was on the same flight back to Casablanca, where he would then head to the Azores. He was preparing for a meeting that would happen later in the fall. Fifteen refugees living on the Moroccan side of the sand berm will meet with refugees living on the Algerian side to discuss their lives. Observing them will be three Mauritanian anthropologists. The hope is that these meetings, which have occurred over the years, will help form bonds within the region. The larger hope for the region is that eventually real peace will break out. The topic to begin the discussion at the gathering will be: The Camel.