Posts Tagged ‘UNHCR’

For Syrian refugees in Lebanon, a drive to build community amid pressing challenges

Communities spring up in the buildings and spaces where families manage to find a spot. Many refugees say their hope is in giving their children a better future.

By Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, published in The Christian Science Monitor, February 27, 2017

Beirut, Lebanon—I remember Syrian children living by a garbage dump near a cement factory where their parents did menial labor when I visited Lebanon three years ago. I remember those living in an unfinished shopping mall with open storefronts, several families camped in a space supposed to be a shop, except that the developer had run out of money and never finished the building. Now he could collect rent from the refugees.

Syrian refugees were pouring into Lebanon in 2014, fleeing the civil war. The United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) and nongovernmental organizations were scrambling to register and provide services for these families, most of whom hoped to return to Syria when the war was over. Because Lebanon has a history dating back to the Palestinian diaspora of not providing camps for refugees, the displaced were finding shelter wherever they could. The effort to get children into schools was beginning. One aid worker described the situation as trying to give cups of water to people from a blasting firehose.

I recently returned to Lebanon to visit the Syrian refugees. I was in Beirut when President Trump’s edict on immigration and his ban on all Syrian refugees to the United States was announced. The ban included Syrian families in Lebanon who had been going through the long vetting process to resettle in the US. Lebanon has the largest percentage of refugees given its population – more than 1 million registered in a country of 4.5 million citizens.

The situation in Lebanon remains deeply challenging, with pressing needs. But it has stabilized. The flow of people across the border is now a trickle, not a flood, and the systems to assist are more firmly in place. When the refugee population hit the 1 million mark, Lebanon changed its open border policy. But the Syrian refugees remain more than 20 percent of Lebanon’s population, the equivalent of 64 million in the US. Last year the United States accepted 10,000 Syrian refugees out of an estimated 4.8 million worldwide.

Three years ago, Lebanon had only 150 schools that had split shifts, teaching the Syrian children in the afternoon. Today half of the Syrian children are in government schools – more than 200,000 children, according to UNHCR officials. UNHCR pays the Lebanese Ministry of Education $600 per child to assist in the cost. Some children may be enrolled in private schools, according to officials, though the remaining are still not in school, including those who work to bring in income for their families, and, in the case of girls, those who are married off as young as 14 or 15.

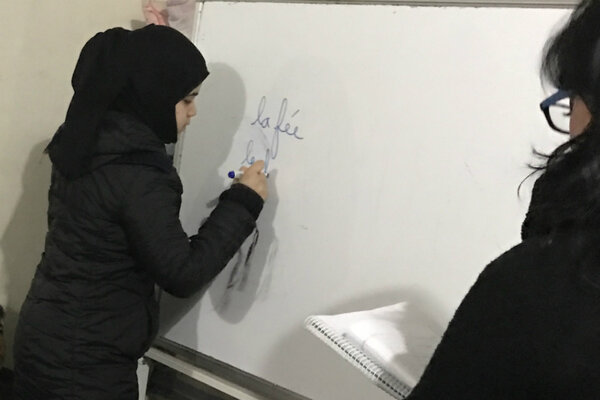

Writing plays and tutoring in French

A difficulty for Syrian school children is language; Lebanese schools teach in French or English in addition to Arabic. One 12-year-old girl dressed in black headscarf practiced French with a local volunteer in a homework support group. The girl has been living in Lebanon for 3-1/2 years. She was in fifth grade when she left Syria, but she’s lost years of schooling, and because she doesn’t know French, she is now placed in third grade. She is friends with some of the Syrian children in her school, but with few Lebanese children. “They don’t like to talk about the same things,” she said. “What do you like to talk about?” I asked. “I want to talk about the war.”

Hasan, 13 years old, remembers going to school in Aleppo, and has been in Lebanon three years. He’s glad to be in school again, but he too has lost several years of education and is in an early elementary class.

For elementary school children, the transition is not as difficult since they can learn French or English, but older Syrian students are struggling. Homework support groups have grown up and are sustained by UNHCR and Save the Children. In Batroun, a town in the North, a Lebanese teacher volunteers twice a week to tutor French. Other outreach volunteers assist in other subjects. One young man, Joseph, helps the children by writing plays and doing small theater productions with them. A Syrian, he receives his work expenses and training. But, he said, “I volunteered to help my people. At the beginning I wanted to volunteer in any sector, but I believe education is very important. I started a small theatrical team, selected the children, wrote small plays with a message, and we perform in a small garden Saturday or Sunday for the community.”

Building communities has been essential for the children and their families, especially since return to Syria remains problematic. These communities grow up in the buildings and spaces where the families live. Approximately 60 percent of the refugees rent apartments, often crowding several families into one or two rooms, carpets and pillows on the floor, a single television in the corner, a light bulb on the ceiling. UNHCR has helped in reconstruction of buildings with an agreement from the landlords that they will rent at reduced rates to the Syrian refugees for a period. Other refugees have built temporary shelters on the roadside. Simple wood frames with tarps and plastic sheeting dot the landscape in the north, perched on farmers’ land where refugee men and women work in fields of orange groves, olives, cucumbers, and potatoes.

Guests, with work restrictions

The Lebanese government has said it is treating the Syrians as “guests” and does not deport them, but the government restricts where the Syrians can work. To get a residency permit, they have to agree not to work except in agriculture, construction, or environment (cleaning) – all low-wage areas. The government also requires that refugees re-register every six months, paying $200 per person over 15 years of age. The cost is prohibitive for many families, so the men in particular live in fear that they will be arrested for not having proper registration, and this limits their mobility in finding employment, according to aid workers.

While refugee services from the UN, nongovernmental organizations, and the Lebanese government have increased in recent years, so have the poverty rates, as families have spent the money they brought with them. According to UNHCR statistics, 70.5 percent of the refugee population live in “extreme poverty,” meaning they live on less than $3.80 per day. UNHCR provides cash assistance, but to only 22 percent of these families. With the cash cards they can buy food, supplies, and pay rent. As winter arrived, additional small payments were provided to help buy blankets, warm clothes, and fuel.

Many of the refugees say their hope is in giving their children a better future, but in Lebanon that future has a ceiling. “At least we have a real school now and one close. It is much easier for our children,” says one mother. But with livelihood possibilities tightly controlled and the possibility of affordable residency curtailed, many parents don’t see an expanding future in Lebanon. UNHCR tries to assist those who want to resettle elsewhere, but even before the recent US ban on Syrian resettlement, the possible openings were diminishing.

“UNHCR’s top recommendation in Lebanon is a waiver of the residency fee so that the refugees are all legally registered and can work. This will help provide employment for them and a work force in needed areas of Lebanon, and income that can then be spent in the local economy,” says Karolina Lindholm Billing, UNHCR deputy representative.

“When you used to look out over Beirut at night, you would see black on top of the buildings,” she notes. “Now you see the lights of refugee settlements there – tents and cooking fires. The refugees have found whatever space is available and gotten permission from the landlords and pay rent.”

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman is a novelist and journalist who has traveled in the Middle East and visited the refugee settlements in all the countries bordering Syria and has recently returned from Lebanon. Ms. Leedom-Ackerman is a former reporter for the Monitor.

(Click here to read the article at The Christian Science Monitor.)

Refugees: The Great Walk Now or Never

The black rubber dinghy had just landed on Mytileni’s rocky beach on the Isle of Lesvos, Greece. The 41 people crammed precariously on the raft quickly dropped their orange life jackets and looked around to make sure their friends and relatives had also made it to land.

A father knelt before his curly headed son, around 3 years old, took off his life jacket, checked his clothing—damp, but not too wet—and tried to explain where they were. The boy smiled, looked about and then spent his time trying to get his heel back into one of his wet sneakers. I was able to help him as his father looked for his wife, who’d made it to land further down the beach. The family had left Aleppo a week ago, waited three days on the Turkish coast near Izmir for transport and now, finally had safely reached the shores of Europe.

From here they would continue their long journey to a new life, which they hoped would be in Germany. Before them lay at least half a dozen train and bus rides and walks with their two backpacks containing all their belongings. Also ahead were multiple registration centers in each country they would pass through.

Along with the 760,000 people who have come through Greece since April, they were embarking on “The Great Walk,” or some call the trek “The Great Wait.” With winter coming and borders closing, it is a “now-or-never” journey as Europe absorbs the largest migration since World War II. Almost half—45%—come through Lesvos, 58% men, 16% women, 26% children, according to statistics from the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR).

As Syrians, they are lucky, if having to flee one’s home destroyed in war can be considered luck. Most Syrian refugees—96-98%—will eventually find new residencies. Syrians comprise 45% of this great exodus. Another third are Afghan, a tenth are Iraqi. The rest are Eritrean, Central African Republic, Iranian, Somalians, Moroccan, Algerians and others, according to figures from UNHCR. The latter four nationalities have slim chances to resettle in Europe.

In the past month access for “direct arrivals” has closed. Only refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan are allowed the onward journey into Europe. These nationalities comprise 85% of those on the move. The rest are turned back. The European Union has also agreed to accept 160,000 in a formal resettlement process, which takes one to two months and requires refugees to accept whatever country they are assigned. Again, only certain nationalities are included in this relocation process—Syrians, Iraqis, Eritreans, those from the Central African Republic and perhaps soon Afghans, according to Alessandra Morelli, UNHCR Senior Operations Coordinator in Greece.

“History is passing in front of our eyes,” Ms. Morelli says at the UNHCR office in Athens. “I feel responsible that we build a Europe that is open and not one of walls.”

In the Lesvos registration site Kara Tepe I met with a group of 21 family and friends who’d arrived earlier in the day. They had come through Lebanon from their village and were part of a small Shia sect of the Alawites. The Assad forces had insisted the men must join the Army at the same time ISIS had come to the village and kidnapped three girls and killed many people and threatened that if the men didn’t join them and convert, they would be killed.

They fled the village, leaving behind a 65-year old father, a lawyer who’d been imprisoned and tortured and didn’t want to leave. Another woman through tears said her 19-year old son was still in Turkey trying to raise money to cross. She would stay on Lesvos until he joined her. Among their group were infants and toddlers, who were now running in and out of the small Ikea houses assigned to the families until they moved on later in the day or the next day.

“I fled not as a deserter, but because I didn’t want to fight,” said one of the fathers. “It was impossible to live in Syria any longer with our family. We needed $12/day to live and could only make $2. I was working in a restaurant; my wife studied French in university and couldn’t find a job. For the last three years there have been no jobs. There was constant shelling. Our children were afraid. There was no future for them, and we are watched on all sides. Planes are constantly flying over; the children aren’t sleeping; shooting is everywhere. When it’s dark, no one goes out.

“But despite all the difficulties we still face, we feel safe now,” he added. “We’ve received good treatment here, enough to feel like human beings again. I want my children to be raised in Europe out of all the bad complexities in my part of the world.”

Harsh stories abound for each refugee, but there are also stories of hope and of an outpouring of good will along the way. Volunteers from Greece and all over Europe have come to assist. There are Doctors Without Borders treating the sick, Clowns Without Borders entertaining the children; there are Families Like Ours from Portugal providing tons of clothes, Green Helmets from Germany putting in wooden floors in the tents, Samaritans are winterizing the shelters with tarps. There is a local Greek mother who donated a stroller and wrote a letter to the mother who would receive it. There are Spanish Life Guards who wait on the beaches in wet suits, ready to go out into the ocean to help those trying to get to shore.

There are local and international nongovernmental organizations—Save the Children, Action Aid, Habitat for Humanity, International Rescue Committee, Red Cross, etc., all taking up specific roles in this migration. There are agencies of the European Union, providing security and registration.

Since early fall the United Nations High Commission on Refugees has been on the ground helping coordinate all these processes. The priorities for the refugees are employment and education for their children.

Their journeys, with variations, look like this: They arrive from Syria into one of the bordering countries—Iraq, Jordon, Lebanon or Turkey. There they likely find a smuggler, pay the fee, wait on the border for their turn, sometimes a wait of several days. From Turkey, they climb on a raft, often at night so they are less likely to be seen, and they take the 4-6 mile trip of 2-4 hours, depending on conditions. Shipwrecks and drowning are real dangers and have taken the lives of hundreds, six Afghans just in the time I was there.

On the beach they are met by volunteers and usually by representatives of the EU or UNHCR and the Greek municipality, who take them to a first staging area, where they are given food, water, the opportunity to shower, charge their phones, and change into dry clothes if needed. They are then put on a bus and taken to the registration centers, where their papers are checked; they are finger printed; their nationalities are sorted out; they are given official registration documents and advised on possible next steps. This process can take 2-8 hours. They have the option of staying the night in a tent or small Ikea house for families.

From the registration center they continue to Athens on a ferry. This they must pay for. Their registration and documents are again checked, and they board buses to Idomeni in Northern Greece near the Macedonian border, where, if they are Syrian, Iraqi or Afghan, they are allowed to cross. They walk from the border to a registration site, enter a large tent with wooden benches and wait to be called to register again, this time for Macedonian papers. After registration, they are given food and water, clothes if they need. At all the centers there are safe places and play spaces for women and children, run by Save the Children and other organizations. Over the loud speaker the announcement of all the services available are repeated in English and Arabic, including: “You don’t need to pay for anything.” Everything at the site is free. They wait in tents or in small Ikea houses or outside if the sun is shining for the train to arrive. The train was late the day we were there, and it is not free. It will eventually take them to Serbia, where they must walk to the registration center and again register for new documents. From there they will get trains or buses to their next destinations with walking in between, making their journey northward to Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, Austria and for many on to Germany or Sweden or other countries.

War is at their back. Their future is focused on their children. Their destinations are partly places of imagination, where they imagine jobs and schools and safety. But the triage is intensifying. Winter is coming. The European Union is paying Turkey three billion Euros to secure its borders and service the three million refugees already in Turkey so that they stay. Quotas are filling rapidly in countries like Germany and Sweden, where refugees perceive opportunities. Through facebook and through families who have gone before them, and from the media, Germany and Sweden and Holland and a few other countries have become their mecca, and countries like Portugal, which is open to refugees, have so far received few.

“They are families like us. We want to help,” said Barbara Guevana at the Macedonian border camp. She is one of the founders of Familias Como as Nossas—Families Like Us—a group of women who didn’t know each other but connected through facebook to assist Syrians with housing, education and transportation to Portugal, which has allotted 4500 spaces for refugees. Seventeen women drove three days to Croatia to meet Syrian families, taking with them clothes and food and assuring them Portugal was waiting to welcome them.

“But people don’t know about Portugal,” said Ms. Guevana. “In Arabic the name means ‘Orange,’ and they question why they should go to ‘Orange.’ We assure them we want them to come. The Portuguese government is willing to fly them to Portugal if they get to Austria.”

This migration is changing the face of Europe and challenging the future of the European Union. “We need to manage borders, not close them,” insists Philippe Leclerc, the new UNHCR representative, who has just arrived to head the Greek operation.

While Germans, French and Austrians were at first welcoming, Eastern European nations like Poland, Hungary, Slovakia have been more resistant. And everyone agrees that the November terrorist attacks in Paris have changed attitudes.

“We need to realize these people are fleeing the terrorists; they are not the terrorists,” said Maureen White, board member of the International Rescue Committee and director of Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies Center on Migration and a fellow traveler on this trip.

As the sun sets, we drive from Macedonia through the official checkpoint, showing our passports at each border as we return to Thessalonica. When we cross into Greece, we find our car behind a caravan of busses filled with refugees and migrants who are being returned to Athens. Today was a major police action that cleared the area called “the Green Field” where those not allowed to cross had started camping and piling up. These are not Syrians, Iraqis or Afghans, but all the other nationalities who hoped to pass into Europe. Nineteen hundred people in 49 buses will be put up for the night in the old Olympic facilities in Athens and in the morning told their options, including applying for asylum in Greece, an unlikely outcome, applying for resettlement, an option at the moment only for Syrian, Iraqi, Eritrean and Central Africans or returning to their countries of origin.

Syrian Refugee Tsunami

We’d come to visit a Syrian refugee camp on the Turkish border. When we arrived in Gaziantep, a bustling ancient city just 30 miles from Syria, we were told by United Nations representatives that a battle was going on across the border that day. A bullet had struck a house in the nearby refugee camp so our visit was canceled for security reasons.

The following day a fuller story emerged. In the Syrian town of Jarabulus just 3km over the border, the battle had been especially brutal. At least 10 men were beheaded and their heads mounted on spikes to terrorize the community. The Syrians from the town were now fleeing to Turkey and away from the al Qaeda-linked fighters.

This particularly grisly battle underscores the horror and tragedy facing the almost nine million Syrians (6.5 million in country; at least 2.3 million outside the country) seeking security. Aid agencies estimate at least half the Syrian population of 22.4 million is in need of humanitarian assistance, and as many as three quarters of the population will be in need of aid by the end of 2014.

In the past two months I’ve visited Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey—the four main countries absorbing this historic exodus from the three-year old Syrian civil war and have witnessed a human tsunami. Acknowledged as the worst refugee crisis in a generation, the outflow of Syrian citizens mounted a 500% increase in many areas in the past year, a figure threatening to explode further in 2014 if no progress is made in the current peace talks getting underway in Geneva. Small corridors of security for exiting women and children as recently proposed for the city of Homs will add to the momentum of the exodus.

Each of the bordering countries has responded differently to the crisis. All have opened their borders, at least the first two years. The United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) has fanned out across the region to assist according to each country’s mandate, with aid and aid workers in their sky blue vests arranging registration, locating or establishing shelters, food, medical care and education and coordinating with other nongovernmental organizations (ngos), but few have experienced a crisis of this magnitude.

I recently returned from Turkey and Lebanon, both of whose borders are still open.

Turkey has officially registered more than half a million refugees and given one-year residency permits, but many more refugees are estimated within Turkish borders and the permits are already expiring. The government has built and manages state-of-the art camps, having spent $2 billion for 20 camps along the border. These include both tented camps and camps with temporary container housing. The camps include classrooms, play areas, meeting areas, libraries, TV rooms, even rooms of washing machines in the two Nizip camps we visited. The camps are at a standard not seen before, according to one UNHCR official. However, because the camps were established by the Turkish government, not the UN, they are much closer to the border than is standard.

Within the camps are schools with a Syrian curriculum, overseen by the Syrian National Council, a coalition of Syrian opposition groups based in Istanbul, which has expunged Assad from the textbooks and republishes the textbooks and provides books to the schools. The brightly colored school rooms are largely staffed by Syrian teacher refugees in the camps. Camp officials claim between 70-90% enrollment.

According to Karim Atassi, the UNHCR Deputy Representative for the region, one Turkish official noted: If we don’t carefully look after the Syrians gathering in Turkey (especially the young), they will be a time bomb for us. The Turkish government consults with UNHCR, which is recommending that the government certify the Syrian curriculum and education this year so students can get credit and certification for their education.

Approximately 250 Syrian students, who have taken Turkish language classes and passed the TOFEL language test, have been given university scholarships. “Turkey has helped us a lot,” said one student, a young man set to study economics. He and his four friends in the refugee camp who also received scholarships had been in university in Syria but now must start all over again in a new field, because there was no space in their former fields of study. They were not certain whether the scholarships included a living stipend. Several of the students were married and had families, but they count themselves among the lucky. Sitting with them was a slightly older student of 27 who wanted to finish his study of law, which he had almost completed in Syria, but he had not received a university scholarship.

The challenge in Turkey and in the other countries is that only a third of the refugees live in camps. The rest—between 300,000 up to 700,000 in Turkey—live in the cities and villages and don’t have access to the same services. In all the countries the urban and unregistered are the biggest challenge and the ticking time bomb.

Lebanon, whose borders also remain open, has not provided nor allowed provision for official refugee camps or shelters lest the refugees “be tempted to stay.” Proportionate to its size, Lebanon has absorbed the largest share of the refugee population.

“In September, 2011 U.S. Secretary Clinton said to us, ‘Don’t worry. Accept the people from Syria, and we will help you,” said acting Prime Minister Najib Azmi Mikati, in a meeting at his residence in Beirut. “At the time there were 10,000 refugees. We said, ‘Never mind, we can handle it. Now there are more than 900,000 refugees in Lebanon, a country of four million people. They represent over 20 percent of our population. It may even be more. Some estimates are as much as 1.3 million.”

In Lebanon refugees are registered by UNHCR and then receive services and assistance with food, medicine and rent. Some have been able to find apartments; many have landed in temporary shelter, including at an abandoned shopping mall in Tripoli or in shacks at a cement factory in the southern city of Saida, where they work for rent, or at a Palestinian refugee camp in Beirut.

At least 75% percent of the refugees are women and children in all countries. After shelter and food is found, one of the biggest challenges is education for the children. That and long, idle days of waiting…waiting for husbands to find work, for relatives to get out of danger and arrive…and most of all waiting for the war to stop so they can go home. At a point, and that point has long passed for many, the waiting becomes a way of life, corrosive to the spirit. How does one fill one’s days and one’s children’s days when there is no work and no school, asked one woman.

At one gathering of women in an abandoned shopping mall in Tripoli, Zaira, a mother of four sons ages 7 to 13 said all her children had been in school in Syria, but in Lebanon, there is no available school nearby. What will happen to their education? she asked. Many of the refugee children have missed one or two years of school already.

UNHCR and ngo’s offer some transportation to schools if there is space, but in Lebanon 70% of the education is private and the 30% public schools are filled, even with second shifts. Refugees are also finding barriers of language since instruction in Lebanon is traditionally in English and French and only occasionally in Arabic.

UNHCR and the local ngos also offer vocational training such as hair dressing, computers, and sewing, but jobs are not assured after the training. Some men and older children refugees have found manual labor or part time agricultural work, but mostly the population waits.

In the abandoned shopping mall over 900 people live in the shells of stores that had never been finished. The 30 owners of the abandoned mall have returned and now collect rent. The advantage of the mall as shelter is that the walls are solid; there is a roof; electricity has been strung in. Laundry is hanging everywhere. There are no shops, except for one small candy store near the entrance and a small improvised vegetable/fruit stand, but there are dozens of satellite dishes. Even in the most improvised shelters refugees manage to find televisions to connect them to the outside world and sometimes back to home.

In one shop/residence women gathered sitting on the floor covered with a brightly colored mat and mattresses along the wall. One woman from Hamah shared her story while others nodded in agreement: “I left because of the constant bombing. We couldn’t leave the house even to buy bread. Before we left home to come here, we were internally displaced, moved from one place to another to avoid the shelling. My brother got killed. To get here we walked, rode a bike with our two boys and two girls, sometimes walking, sometimes biking. We left Hamah to Homs. It was easier to cross on the northern border. There are problems on the Syrian side of the border. The Syrians try to split families. It took us two days to get here. We brought nothing. We arrived with nothing. People here had extra mattresses and gave them to us. The biggest challenge is now rent. In Syria we were working as farmers [but we don’t work here].

“As the situation has gotten worse in Syria, we’ve been able to talk to a cousin but can’t talk to our parents. There’s no reception. First we went to Beirut for 27 days where we knew people. After that we came here because my sister-in-law lives in the area, and we stayed with her until we found out about the rooms here.”

Some estimate that by the end of 2014 the flow of refugees out of Syria could double with over 4 million total outside the country. Will the four buffer countries of Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey be able to continue absorbing the refugees without severe destabilization of their own populations? While countries like the U.S. and countries in Western Europe have contributed financial aid, they have admitted only the tiniest trickle of refugees into their countries. Last year Germany admitted 5,000 Syrian refugees, and the Germans were among the more generous. The United States has accepted 90.

Those interested in learning more and in assisting in this crisis can contact among the following organizations: UNHCR, International Rescue Committee, International Committee of the Red Cross, Save The Children, Refugees International.

The Last Colony?

The desert stretched out like a beige patterned quilt as far as the eye could see. The pattern looked like birds’ wings or boomerangs in the sand as the plane descended, then the swirls of sand resolved into rocky ground. In the distance a few concrete buildings rose around the pink watch tower of the airport as I landed in Laayoune in the Western Sahara.

A 103,000 sq mi stretch of desert and coastline twice the size of England, larger than all of Great Britain, the Western Sahara is called by some “the last colony.” Extending south between Morocco and Mauritania with almost 700 miles of coast edging the desert, the region has been in a political quagmire for the last four decades. Spain and Mauritania renounced their claim to the area in the late 1970’s, leaving only Morocco and the indigenous Sahrawi’s in dispute.

In February, 1976 the Sahrawis declared a sovereign state, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). For almost 16 years (1975-1991) Moroccan forces and the Sahrawi indigenous Polisario Front engaged in armed struggle. For the next 22 years the United Nations has overseen a political limbo. A referendum on independence was promised but has been stalled year after year.

I first became interested in the Western Sahara in the early 1990’s when chairing PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. The stories of torture and the conditions in the prisons of the Western Sahara were as grim as any I encountered. Many died and never made it out of the prisons, which were run by the Moroccan security forces. There were also bleak reports from prisons run by the Polisario rebels. I still remember stories of writers who took their bar of soap they were given each month and wrote poems on their trousers. The writers then memorized each other’s poems as a way of staying sane. They also scoured the prison yard in the one hour they were given each day and found scraps of paper and used coffee grounds to write their forbidden verses. Their stories demonstrated how one endured—through fellowship and a flight to the imagination.

Since that time the armed conflict has officially ceased; Morocco has granted amnesties, and most of the prisons have allegedly been closed, but there are still reports of “black jails” with grim conditions even in the capital. There are large areas where no one is allowed to visit.

My visit was brief, the visit of a tourist. I hired a taxi recommended by the small parador where I stayed, the hotel itself recommended by a friend of a friend who worked at the U.N. My driver spoke Spanish and Arabic, some French and little English. I speak English, some French, less Spanish and very limited Arabic, but we managed. I asked him to show me around the city then take me into the desert and then to the beach.

Those living in Laayoune are living their regular lives, women in long djellabas with head scarves, children going to school—you can hear their chatter and laughter on the streets—men also in djellabas or slacks selling in the shops and markets. But the area is a high security zone. The U.N. and the Moroccan security are present, and travel is restricted. No one is allowed too far east where a giant man-made sand berm separates the Moroccan-dominated region from the smaller Saharwi Polisario region near Algeria. Land mines are said to be scattered throughout the no man’s land in between.

In my 24 hours in the capital Laayoune, a city of around 200,000 with 70% of the Western Sahara’s population, I was stopped at six checkpoints. Two were on the way to the desert where a two-lane road stretched through the sand and rock. Any other journey in this area would need to be made with an off road vehicle or on a camel, but I saw only a few camels.

At one point on the way from the desert to the beach, I was delayed for 45 minutes with my passport examined twice. Everyone was friendly; I was friendly. A policeman with a moustache wearing a crisp blue uniform with white belt and military hat, looking very French (though the larger influence in the Western Sahara is Spanish), stood in the middle of the highway to stop us then came over to the taxi.

“Bonjour,” he smiled at me. “Bonjour,” I replied. “Passport?” he asked. I handed him my American passport. My driver had already called another policeman whom we waited for at a designated place in the city to get permission to go to the beach. At the beach are the fish processing plants and a phosphate plant as well as a promenade and beach and the Atlantic. We were given permission so I’m not sure why we are being stopped.

“Profession?” he asked. “Ecrivan,” I answered. “Journaliste?” he asked with suspicion. “No…ecrivan…romans.” I smiled. He smiled. He took my passport and went back to his car where he and the driver conferred for fifteen minutes. I watched them in the side mirror and wondered if I should get out of the car but decided I should stay inside. He returned to the car and gave me back my passport. He smiled I smiled. But still he didn’t let us go.

Meanwhile cars and a few trucks passed by without being stopped. They were driving south either towards the beach or all the way down the highway to Mauritania, over 600 miles away. I’ve been told this is a smugglers’ route. I wondered what traffic might have passed while I was being checked.

The driver returned and asked for my passport again. Another 15 minutes went by. I continued to watch them in the rearview mirror. Finally I got out of the car. I didn’t walk towards them. I just stood leaning against the taxi in the wind—a lone American woman traveling in the desert, sitting in the front seat of the taxi because it gave me a better view. I was probably not a sight they were used to. After almost 45 minutes, we were finally released. I don’t know what the conversations were. The driver told me it was about his license plate; one of its numbers was wrong; he was given a fine. Then why did they need my passport…twice, I asked. But he had no answer I could understand. Instead he took me to lunch at a restaurant on the beach, which I thought was either his father’s or his father worked at, then he invited me to his home, where he told me his mother had made me tea. His mother didn’t appear, but a tea service was set up, and he served me the delicious sweet mint tea in an elaborate Moroccan tea ceremony. When I paid him at the end of the day, I tipped him enough to pay the fine though I didn’t really know what happened, but we were smiling.

At the hotel, the U.N. representative who is a friend of a friend picked me up to go to the airport. Coincidently he was on the same flight back to Casablanca, where he would then head to the Azores. He was preparing for a meeting that would happen later in the fall. Fifteen refugees living on the Moroccan side of the sand berm will meet with refugees living on the Algerian side to discuss their lives. Observing them will be three Mauritanian anthropologists. The hope is that these meetings, which have occurred over the years, will help form bonds within the region. The larger hope for the region is that eventually real peace will break out. The topic to begin the discussion at the gathering will be: The Camel.