Posts Tagged ‘Africa’

Reflections on Spring

The geese have gone. Dozens have abandoned our lawn and veered back to Canada for the spring and summer. They will return when the temperatures again drop up North.

For now cherry blossoms are blooming, daffodils have sprouted, and green buds are exploding on all the trees. Spring in its mercurial moods has come to the Chesapeake. The last (I hope) snow and ice storm of the season passed through a few weekends ago. Bright sun and balmy temperatures warmed us last weekend; this weekend hovered somewhere in between, though Monday morning dawned below freezing again.

Even as this fraught globe balances between war and peace in Europe and drought and famine in areas of Africa, and genocide in regions of Asia, this earth of ours spins on its axis. The seasons continue to rotate. As humankind, most of us live lives focused on the needs of day to day as the peril from afar flickers on the screen. In the nighttime hours this flickering in the dark heightens and gives pause, intensifying as sleep eludes. But then the day dawns and the sun rises, and the earth again spins its course. Looking closely near and far, we witness (and can do) deeds of kindness, and these save us and the planet from the apathy of despair.

Here I post some photos of the season in appreciation of the beauty that I wish could unite us and that might at least find a home in imagination if not in fact.

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Photo credit: Teresa Gadow

Democracy in Africa: Who Can Chat with Kabila?

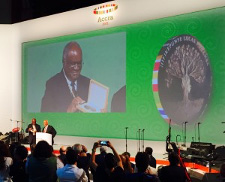

I returned last week from two conferences and a debate back to back in Africa. The Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which has developed an index on good governance and transparency in Africa, gave its annual prize to a former African leader, followed by a day-long discussion on “African Urban Dynamics.”

The Africa Report Debates inaugurated its series with the question: “Democracy vs. Development.”

And the International Crisis Group, an organization dedicated to analyzing and offering policy recommendations for current and potential conflicts worldwide, (and on whose board I serve) gathered its Africa program for an internal analysis.

From the gatherings of eminent African leaders, policy makers, scholars and commentators I took away the following contradictions across the continent:

–There is an expanding and active civil society at the same time there are spreading and virulent extremists and criminal networks.

–There are growing numbers of working democracies at the same time entrenched leaders are trying to change constitutions to hold onto power in single-party states.

–There is developing urbanization offering services and employment for citizens while slums and marginalized communities expand.

The debate “Democracy vs. Development” concluded overwhelmingly that the two must go hand in hand.

“Fast and equitable development and diversity come through democracy,” according to Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Ethiopia. But he added, “Democracy is a process. It matures over time and grows from the inside. It can’t be prescribed. It needs institutions and education. We don’t need paternalistic intervention.”

Ethiopia was pointed to throughout as making significant economic progress. But in a break between panels, I asked Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus about the restrictions on freedom of expression in Ethiopia and the number of writers and journalists now in prison there. His answer: “They broke the law.” Their imprisonments have been challenged by major freedom of expression organizations like PEN International, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty, Committee to Protect Journalists, as well as by African PEN centers, I pointed out; this is not a positive sign for healthy government. He and I did not resolve the question between us.

Good news and reasons for hope on the continent include the peaceful elections and transfer of power this year in Nigeria, which has a strong and vocal civil society even as it struggles with the radical extremism of Boko Haram in the North and with criminal trafficking. Also positive is the immanent transfer of power through elections in Burkina Faso, where citizens rose up peacefully last year and opposed the extended 27-year rule of its leader, demonstrating a strengthening civil society. Ghana, where the conferences convened, held peaceful Parliamentary elections while we were there.

“We need heroes,” said Mo Ibrahim, who initiated the conference and the award which was given to the former President of Namibia. Hifikepunye Pohamba won the $5 million prize for “forging national cohesion and reconciliation at a key stage of Namibia’s consolidation of democracy and social and economic development.”

“We must reject the manipulation of the Constitutions,” said former President Pohamba in his acceptance speech. “No individual or group of people should be allowed to abuse power from democratically elected leaders with impunity.”

Electoral transitions in East, West and Southern Africa could unhinge or advance their regions, including in Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Cameroon, Uganda and Zimbabwe. In many of these countries, the current presidents are hoping to hold onto power past constitutional limits which they are trying to alter or past public tolerance. Outcomes of these elections will be important indicators to watch.

Informal conversation outside the symposiums:

“Who can chat with Kabila?” (President of DRC). “I understand he’s scared. His father was killed here.”

“Who can offer him immunity?”

“Can he have a soft exit?”

“Will he exit?”

“I don’t think so.”

Behind all the statistics and the headlines, the story after all is always about people.

Africa of the Mind: Friends Real and Imagined

(This blog post originally appeared on www.africa.com, a website that features arts, culture, news, travel and commentary about Africa.)

Africa for me began in imagination. I was writing a novel The Dark Path to the River, which had an unnamed African country as the back story for a drama at the United Nations. The African characters started talking in my head, telling me their stories.

I had read widely about Africa, but at the time I had only been to Kenya on a traditional safari. I continued reading African literature, audited courses on African folklore and politics. While writing the book, I returned to Africa, to Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi, where I visited schools and children I’d been engaged with through a nonprofit organization. I listened to the rhythms of the languages, to the songs, observed the colors of the green hills, the red dirt, the fuchsia, orange, yellow and blue flowers, the clothing of the same astonishing colors and patterns. I met with fellow writers and artists.

I have since returned to Africa dozens of times. I’ve visited schools in east, west, central, and southern Africa. In Uganda, I’ve plowed through the bush in a jeep to arrive at classrooms in a clearing whose materials hung from the roofs of huts with no doors so the cows of the pastoralist herders wouldn’t trample them. I’ve visited brick schools built by villagers in Malawi where the children sat on the extra bricks for stools: I’ve sat in classes in bullet-scarred schools that have been rebuilt after the civil war in Sierra Leone. In Ethiopia I’ve participated in a village bridal ceremony, have sat around smoking fires in villages in Mali eating goat and rice, have walked through the modern capitol buildings of Abuja, Nigeria, watched the sun rise over the Indian Ocean in Tanzania and set on the Atlantic in Sierra Leone.

I’ve listened to literature as I traveled in Ghana and Senegal, where writers are revered since the first President of Senegal, Leopold Senghor, was a world renowned poet. I’ve ridden a camel through the desert in Morocco and galloped on a white stallion at sunset in the Sahara in Egypt, stood awestruck at Victoria Falls, watched a bird tiptoe over lily pads on top of the water in the Okavango Delta in Botswana, and witnessed the charging, turbaned horsemen in the Durbar in northern Nigeria. I’ve stood silenced in the slave holding areas peering through the portals where human beings were shipped to market from Gorée Island in Senegal and Elmina Castle on the Gold Coast of Ghana.

From modern capitols to the remotest villages without electricity, where villagers share the river with the baboons, lions and crocodiles, Africa encompasses centuries in one continent, often in one country. Through my work as a writer and with organizations in education, I’ve had the opportunity to visit and work in at least 15 countries over the past decades.

Africa for me began in imagination with people and has expanded with people– with the illiterate father in Mali who advocated for his daughter to go to school so she could help him when he went to market and assure he wasn’t cheated, to the witty Nigerian poet who asked in his poem, “Who Killed Macbeth?”and had a host of citizens blaming each other, to the courageous newspaper editor who gave his life in fighting corruption in the Gambia, to the woman organizer who organized women all over Sierra Leone for good government and then had the audacity to run for President herself and later to cheer when her good friend in neighboring Liberia actually won.

Many journeys to Africa are still ahead, I hope. Now I visit real friends as well as imaginary ones.

When the Crowds Go Home, Ideas Keep Traveling

The crowds have left; the reviewing stands, disassembled. The reflecting pool is frozen with sea gulls light-footing across it. Washington, DC has held its grand party. For three days, everyone was on foot, bundled in coats, scarves, gloves and walking everywhere–to the Mall, to the Capitol, to the White House (or as close as one could get), peering over barricades, hundreds of thousands of people.

Most of those who came to town have returned to all the states in the union from which they came. Those from the more than 100 foreign countries here to watch the Inauguration have also returned. As the full working week commenced in Washington, snow flakes were falling; the sky was cloudy, and the Potomac River, crusted with ice at the edges, waited for spring.

But the spirit remained. And the consequences of this global gathering were only beginning. Among those visiting Washington were women from the world’s conflict regions, women engaged in peace building, who were gathered to share experiences and also to study and watch the U.S. electoral process, particularly as it might apply to their circumstances and lives.

At a conference, sponsored by the Initiative for Inclusive Security, women from Afghanistan, Bolivia, Israel, Kashmir, Lebanon, Liberia, Palestine, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Uganda and other areas came together for training, exchanging experiences, and working on peace initiatives around the globe. After the main conference, a dozen women met in a side room around a table with tea and coffee and strawberries, women from Uganda, Sudan, Sri Lanka, Iran and the U.S. to consider how to get more women in the electoral process in these countries.

The focus quickly turned to the upcoming July elections in the Sudan, where 25% of the seats have been set aside for women. At the table were Josephine Akulang Abalang from the Southern Sudan and Lina Zedriga Waru Abuku from Northern Uganda. These two women live in neighboring countries and regions, both of which have been devastated by years of conflict, separated by a few hundred miles and bad roads, both regions in a fragile state of peace.

Both women have considered running for office in their countries. However, Lina’s husband, who had been an opposition politician, “disappeared” eight years ago, and her children begged her not to take the same risk so for the moment she will stay out of the electoral process, but she is helping others. A lawyer, she manages the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 Project which seeks to empower women for peace and reconciliation.

“We are not victims; we are the stakeholders,” she says and repeats her mantra, “Nothing about us without us.”

She and the other women around the table focused their experience and contacts on Josephine, who may well embark on an electoral bid. At the height of the civil war in 1992, Josephine fled the Sudan on foot, along with 500 students; she was one of only six females in the group trying to get to Uganda. Instead she was captured by the Sudan Peoples Liberation Army and forced into military training, but eventually was released. She made her way to Kenya, where she was awarded a scholarship in Canada and earned a bachelor’s and then a masters degree in international relations. Currently working for the UN and for the government in the Southern Sudan on disarmament, she is the first from her village to graduate from school and would be the first woman from there to run for office.

She and Lina and the women from Sri Lanka and Iran said the impediments for women to seek election were psychological and systemic. “Women are 60 % of the population in the Southern Sudan, but women lack confidence,” Josephine said. “Women think they need certification to run.”

The women around the table representing civil society and experience in their communities began to strategize on how to get the Sudanese women the training, skills, credentials, and the solidarity of a community behind them to run for office.

There are immense challenges facing the Sudanese 2009 elections—gaps in voter education, logistical support for elections during the July rainy season, special difficulties for free and fair elections in Darfur, where rebel commanders didn’t allow the census and large areas continue to be plagued by armed opposition. Aid offered for election procedures has often been held up by the national government. But there are women starting to organize with the hope that at least on the ballot and then in the meeting rooms and around the tables where decisions are made, women will sit and bring to the issues and problems their voices and ideas.

Back in Washington, the women are seeking support –both financial and technical—for their efforts for gender parity in the Sudanese government and in the peace process. The call will also begin to go out to women around the globe who left the Sudan in the wider diaspora to return and run for office.

There is not much time until July, notes Josephine. But the work has begun.

Election: Growing Into Ideals

I went early on election day to vote at the polling station in the church on the cobblestone street in my neighborhood. The lines snaked down the block as neighbors read their morning papers, chatted, visited each other with their dogs on leashes and waited to get inside. After I voted, I went to the airport, and before the polls closed, I flew out to Africa.

When I arrived in Amsterdam, the big television screen outside the airport announced that Albert Gore was the next President of the United States. I went to sleep for a few hours in an airport hotel before my connecting flight. When I awoke, the television announced George Bush was the next President of the United States. I boarded the plane, arrived hours later in Malawi and learned that the United States did not yet have a president.

For the next ten days in Malawi and Ethiopia I attended meetings, visited schools in villages and at every opportunity tried to find a BBC broadcast to let me know who was the next President of the United States. The local press began to write stories to inform Americans how to conduct an election. The banana republic of the United States of America made people smile as everyone watched all the machinery of government at work as the country tried to sort out its leadership. When I arrived home, there still was no new President.

Indications are that the election of 2008 will not be as close, but it too will be a historic election. Whoever wins, barriers will fall, and the profile of leadership at the top will change in the United States. History will only really be made, however, as the sentiments are shed which once barred women, African Americans and others of color from opportunities.

As we’ve watched what has seemed like an endless electoral process over more than 20 months, we have also been watching the country coming to terms with itself and its ideals and its history. The ugliness and slurs that have accompanied part of this election for the most part have been dismissed by the electorate who wants more and insists that we grow up and into our national ideal of all men and women as created equal.

The other day I was discussing with several young voters why this election is so unique. In addition to the specific ground-breaking profiles of an African American and a woman candidate, this election in the U.S. is the first in over 50 years when no candidate is a sitting President or Vice President. The field and the possibilities are wide open.

I plan to stay around this year and watch the returns. In 2004, I was also in Washington, watching the returns with friends. The lead in that election changed several times. At one point I looked around the room of experienced Washingtonians, many couples in long marriages who worked at senior levels in and outside of government. I realized that almost every couple in the room had canceled each other’s votes. When I tell that to friends from other countries, they are always surprised, yet it is more common than one might expect in Washington. For all its partisanship, the city is peopled with professionals who may vote on one side, but in their professional lives work to find ways to cooperate. They understand that for the country to run well, everyone has to work together.

I’m hoping this year, whoever is the victor, he/she will have the benefit of all the citizens in the difficult tasks ahead. If not, then I’ll look forward to reading the press in other countries to advise us how to do that.

African Snapshots

Nigerian Night

The night sky swarmed with pale insects like snow flakes fluttering outside the window of the airplane as it landed at the small airfield in Northern Nigeria. At first they looked like moths, but they were hundreds…thousands of grasshoppers diving into the headlights and fuselage of the plane. Were they cruising the night sky, interrupted by our descent, or had the lights and the hum of the airplane drawn them to their end?

Inside the terminal a luggage belt creaked as bags were pushed one at a time through a small portal onto a set of rollers. When the lights went out and the terminal fell dark, we waited, but the power didn’t return. One by one cell phones flipped open– small arcs of light aimed at the weathered belt as the passengers from Lagos searched for their bags. Dragging suitcases behind us, holding cell phones in front of us to light the way, we plunged into the warm night.

I was in Nigeria as a board member of Human Rights Watch which held meetings there last year. We spoke with government officials after a dubious presidential election. We met with lawyers and human rights activists and teachers and judges and other members of civil society. See HRW reports on Nigeria. We brought experience, research, and expectations. We gained further experience, laid out the expectations, found bridges and absorbed the cacophony of the night.

Tanzanian Morning

On the eastern edge of Africa on the coast of Tanzania the sun rises out of the Indian Ocean like a giant topaz transported from the sub-continent. Around the sun the ocean crashes against the rocks on the coast of Dar es Salaam.

After breakfast I climb into a four-wheeled drive vehicle to go outside the city to visit schools in the countryside where children and teachers are reading and writing and telling stories in Kiswahili and making books to share with other children in the local language. The Children’s Book Project, started in Tanzania in 1991 and has assisted in bringing hundreds of books to publication, distributed these paperback readers into schools, set up libraries in the schools, and trained teachers and artists on how to write and illustrate books and how to teach with these readers. The schools where the CBP is involved have regularly out-performed many of the schools in the country.

In one classroom students perform a story they have read in one of the storybooks. Tabu wa Taire was written by a teacher and tells of a young girl who doesn’t listen to her parents and prefers to play rather than work. One day she wanders too far from home and is captured by a man who puts her inside his drum. Her parents and the village look everywhere for her, but can’t find her until the man comes to their village to play his drum. Someone hears crying from inside the drum, and there the village finds and rescues the girl. The students act out this story for the class and the visitors and end with a celebratory concert on the drum and orange fantas all around.

Ugandan Afternoon

We drive through the bush along a narrow dirt road, the sun beating on the closed windows, the trees hanging down over the path, crowding the road on both sides so that the 4-wheel drive car is literally pushing back the brush as we plow carefully around the turns, occasionally dodging another car or long-horned cattle who amble across the one-lane road to graze on the other side.

We are several hours outside of the capital Kampala and over an hour off the main road, rocking from side to side in the dense undergrowth when suddenly we come to a clearing and a school. The school’s red earthen huts rise from the ground with tin roofs. There are no doors on the huts. There are few books here, and the learning materials hang from the ceilings so that the cows, who can wander in and out of these classrooms, won’t destroy them.

This school is for 75 children of pastoralists–families who make their living tending cattle, moving from place to place with their cows looking for grazing lands. The children usually travel with their parents and don’t have an opportunity to go to school. But here in the clearing, on land donated by one of the more successful in the community, a school has been built; the roofs have been donated by the son of one of the wealthier families. Teachers have been recruited and trained by Save the Children. The children in the school are studying in grade levels 1-4 with the hope that the school will be able to add grades as the children grow. Because there is a school, many of these families, at least the women, will stay in the area while the children attend classes. Some of the women are discussing how to keep the cows out of the classrooms.

From the Edge of the Indian Ocean

I’m sitting looking out at the Indian Ocean from the eastern edge of Africa in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. It is Labor Day, at least in the U.S., though in the U.S. it is actually still Sunday night; but here it is morning with billowing white clouds, blue sky, palm trees, sun shining through—the end of winter in the Southern Hemisphere.

It took 17 hours of flying and a few hours of waiting in Amsterdam—roughly 20 hours to get here. When I arrived in the hotel room last night and the bellman turned on the TV, the BBC in a pulsating picture and sound was reporting on the approach of Hurricane Gustav to New Orleans and the interruption of the Republican National Convention. Was this important news in Tanzania? It was, in any case, the BBC news, and I was interested but couldn’t help but note how far one can go and still have America follow.

Glass Beads: the Color of Hope, and a Peace Corps on Steroids

This past Sunday in the late summer afternoon with a thunder and lightning storm at two, then blue sky and sun by four, we held a small family barbecue to welcome home from Africa the daughter of a good friend and to send off that night to Africa our future daughter-in-law. Both young women are graduate students in International Relations. The first was working in a refugee camp in Ghana with families soon to return to Liberia. The other, a PhD student, is researching the role of education in post conflict Uganda and earlier in the summer was in Malawi, where she and other graduate students had started a nonprofit to raise money for girls’ scholarships to high school (Advancement of Girls Education—AGE).

Our friend’s daughter had brought back a bundle of glass bead jewelry—blue and brown beads, black, red and white beads, etched beads, green and yellow beads, and red, white and blue beads all strung together in an array of bracelets and necklaces–as well as brightly colored children’s clothing, all of which she spread out on the table. She is selling these and will send the proceeds back to the refugees and the surrounding community; she’s also raising funds for at least one high school scholarship for a young man who helped her during her stay at the refugee camp.