Posts Tagged ‘Ukraine’

The Power of One: Dissent in Russia

With the war in the Ukraine front and center in the news, I can’t help thinking back to my Russian colleague from PEN, the General Secretary of Russian PEN Alexander Tkachenko, or Sascha as we called him. I wonder how he would have responded to what is unfolding. During his tenure at Russian PEN, he stood up and argued with Vladimir Putin face to face on behalf of Russian writers and resisted when the government tried to close down PEN in Russia.

Sascha was complex—a former professional soccer player, a Tartar, son of the Crimea, a poet. Those who knew him may still hear his voice on the floor of PEN Congresses challenging his government’s imprisonment of writers, apologizing to new Afghan PEN delegates for his country’s incursion into their country, or remember Sascha swimming off the coast of Perth, Australia in spite of the signs warning of sharks or singing and reciting his poetry at the Writers in Prison Conference in Denmark, or strategizing with the Writers in Prison Committee in the hills of Nepal.

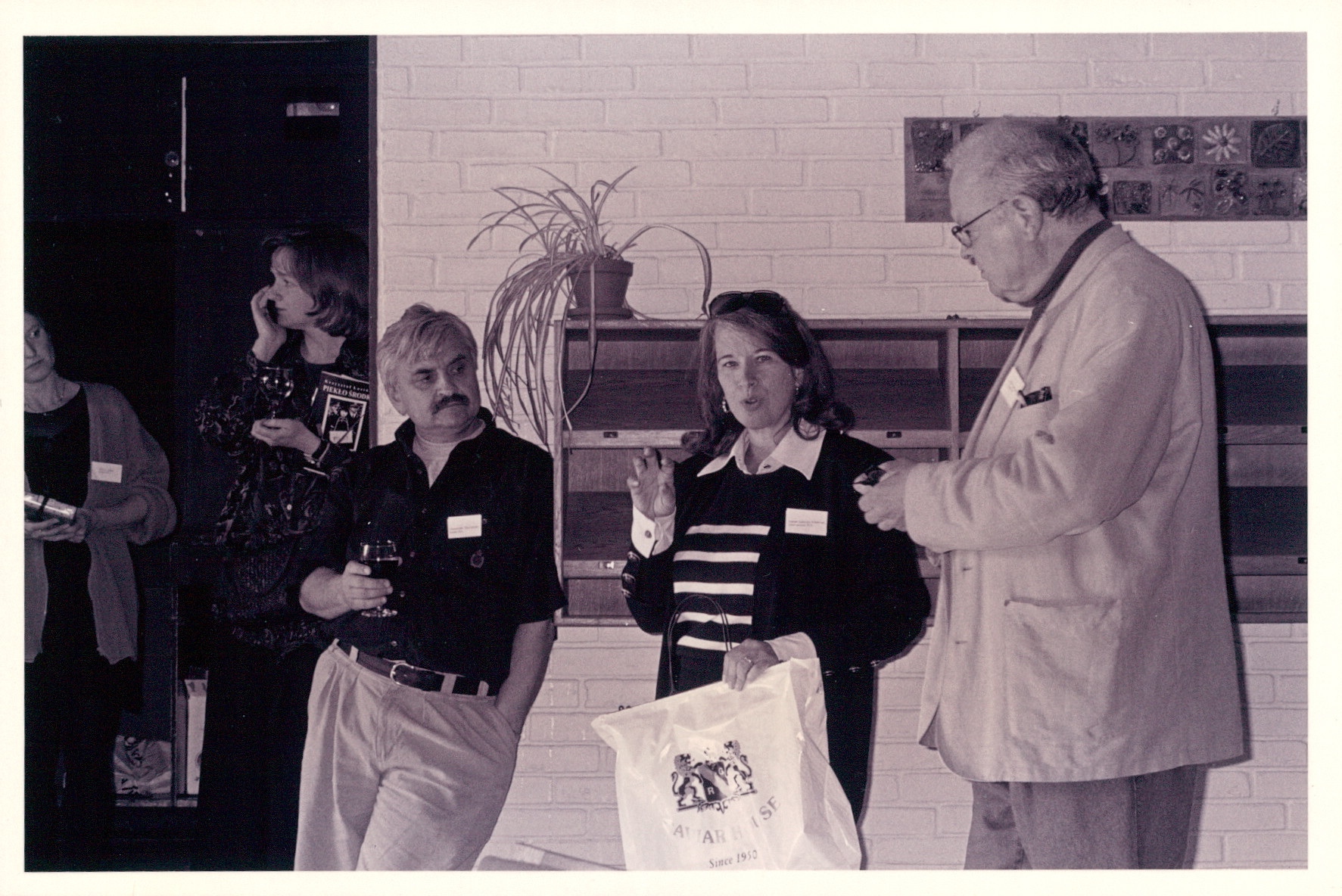

Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Chair of PEN International Writers in Prison Committee), and Niels Barfoed (Danish PEN) at the first Writers in Prison Committee Conference held in Helsingør, Denmark in 1996

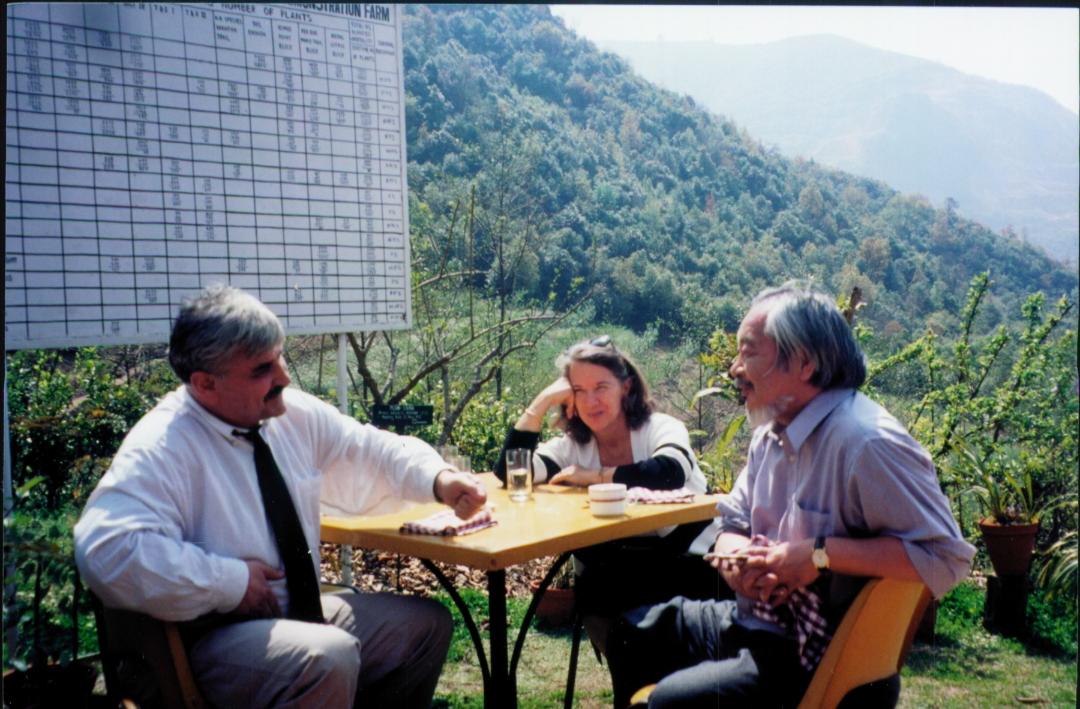

Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (American PEN/PEN Int’l), Mitsakazu Shiboah (Japan PEN) at the 2000 Writers in Prison Committee meeting in Kathmandu, Nepal

When Sascha suddenly turned up dead in 2007 at age 63, we were all shocked. Some speculated perhaps he drank too much vodka; he had a heart condition. We accepted that it was “heart failure” though even at the time, the skeptical voice questioned whether there could have been foul play. As I witness now the carnage in the Ukraine and have since seen the incidents of murder and recently read accounts of those who have been eliminated in Russia in books such as Bill Browder’s Red Notice and the new Freezing Order, doubts again stir about Sascha’s sudden end. I wonder how he would have reacted to the drama playing out today and the closing down of any freedom of dissent in Russia. Today there are additional PEN Centers in Russia—PEN Moscow, PEN St. Petersburg, Tartar PEN, and writers I’m told have differing views among them. But Sascha I feel certain would have defended the right to dissent, to stand up for the freedom to live.

Below is the tribute I wrote at the time. I feel I am mourning Sascha all over again as we mourn the loss of the freedoms he and others struggled for, and we mourn the loss of this vision of a nation.

December 7, 2007

General Secretary of Russian PEN Alexander Tkachenko –Sascha as he is known to his friends—died this week, peacefully in his sleep, we are told. It is hard to imagine Sascha passing anywhere peacefully, certainly not from this world.

As Russian PEN’s General Secretary, this hearty man with salt and pepper hair and moustache, this former professional soccer player and respected poet campaigned fearlessly for writers threatened in Russia. He often stood his ground with officials, bureaucrats, the military and with Vladimir Putin himself. When Putin once visited the Russian PEN offices, Sascha challenged him directly on the rights of writers and freedom of expression in Russia.

Sascha traveled the huge expanse of Russia from one end to the other to lobby, to argue, to advocate on behalf of writers who faced imprisonment by the Russian state, writers such as Grigory Pasko, the journalist and poet who was arrested after reporting on Russia’s dumping of nuclear waste. He championed as well those in former regions of the Soviet Union, in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan. He also spoke out and represented the voice of Russian writers on behalf of imprisoned writers around the world.

Sascha served on the Board of International PEN and attended PEN conferences and Congresses for the past decade. My personal memories are many. I particularly remember standing side by side with Sascha at Istanbul University in 1997 surrounded by riot police as we addressed a crowd of thousands with a bull horn. We were the two representatives of PEN advocating for freedom for Turkish writers in prison.

When the Russian government threatened to close Russian PEN in 2006 because of alleged tax payments suddenly demanded, PEN centers around the world rallied to help. I was International Secretary of PEN at the time and able to meet with Sascha and members of Russian PEN in Moscow as these payments were secured. That meeting was also attended by Rakhim Esenov from Turkmenistan, an elderly former general whose novel had been banned and who had been imprisoned for his book allegedly being “historically inaccurate.” Only a week before American PEN had given Esenov its Freedom to Write Award in New York. He was on his way home through Moscow, where Sascha and Russian PEN offered additional moral support as he returned to face the threats of his government.Rally at Istanbul University [Includes Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN), James Kelman (Scottish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Kalevi Haikara (Finish PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Writers in Prison Committee Chair/American PEN), and Turkish Conference organizer Şanar Yurdatapan]

Russian PEN members meeting in Russian PEN office, including General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (center), 2006

When I think of Sascha, I first hear his laughter and then his arguments, then his particular English; I see his hands waving as he talks, see him reluctant to yield a microphone until his point is made; I see him as he must have been as a young man blocking and running down the field as a soccer player, bobbing and weaving, pushing past those who would try to stop him as he drove to the goal. In his last decades that goal was getting writers out of prison. Sascha was an advocate we all would want on our side should we find ourselves threatened or in prison. He will be mourned and sorely missed.

His funeral is in his home village of Peredelkino December 10, Human Rights Day. He would have liked that framing of time on his passing, though he will not really pass; he will simply rest in our thoughts and rise in our thoughts when courage is called for and an advocate is needed. When a government acts as though it is more powerful than the individual, Sascha’s memory will remind us of the power of one. His voice continues through his writing, and the impact he has had on the lives of writers imprisoned continues.

—Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Reflections on Spring

The geese have gone. Dozens have abandoned our lawn and veered back to Canada for the spring and summer. They will return when the temperatures again drop up North.

For now cherry blossoms are blooming, daffodils have sprouted, and green buds are exploding on all the trees. Spring in its mercurial moods has come to the Chesapeake. The last (I hope) snow and ice storm of the season passed through a few weekends ago. Bright sun and balmy temperatures warmed us last weekend; this weekend hovered somewhere in between, though Monday morning dawned below freezing again.

Even as this fraught globe balances between war and peace in Europe and drought and famine in areas of Africa, and genocide in regions of Asia, this earth of ours spins on its axis. The seasons continue to rotate. As humankind, most of us live lives focused on the needs of day to day as the peril from afar flickers on the screen. In the nighttime hours this flickering in the dark heightens and gives pause, intensifying as sleep eludes. But then the day dawns and the sun rises, and the earth again spins its course. Looking closely near and far, we witness (and can do) deeds of kindness, and these save us and the planet from the apathy of despair.

Here I post some photos of the season in appreciation of the beauty that I wish could unite us and that might at least find a home in imagination if not in fact.

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Photo credit: Teresa Gadow

Reclaiming Truth In Times Of Propaganda

PEN International’s 83rd Congress in Lviv, Ukraine took on truth and words, history and memory, women’s access and equality, cyber trolling, fake news and threats to freedom of expression worldwide, including public panels focused on the three super powers: “America’s Reckoning—Threats to the First Amendment in Trump’s America,” “China’s Shame—How a Poet Exposed the Soul of the Party,” and “Putin’s Power Play—The Decline of Freedom of Expression in Russia.”

At its annual gathering PEN hosted more than 200 writers, editors, staff and visitors from 69 PEN centers around the world in the historic city of Lviv, the Cultural Capital of Ukraine and a UNESCO World City of Literature. Straddling the center of Europe, on the fault lines between East and West, Lviv changed its name and governing domain eight times between 1914 and 1944, passing from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to Russia, back to Austria, Ukraine, Poland, Soviet Union, Germany then back to the Soviet Union and now finally in the Ukraine.

The path of European history cuts through the city and can be seen in architecture, culture and conversation. Though writers celebrated literature in the western Lviv, fighting was still underway in eastern Ukraine and the Crimea. PEN’s Russian center didn’t attend the Congress at the same time a new PEN St. Petersburg center was elected. Other new centers joining PEN’s network included Cuba, the Gambia and South India.

In times of war, the first casualty is truth, noted PEN’s report “Freedom of Expression in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine: External Aggressions, Internal Challenges.” The report and the Congress addressed the aggressive role of propaganda in conflict. In Ukraine, in Russia and worldwide there has been a proliferation of false narratives.

PEN’s report on Ukraine noted: “Despite significant improvements, democracy in Ukraine remains ‘a work in progress’ and, among other things, severe challenges to the enjoyment of the right to free expression remain. These include the use of the media to foster political interests and agendas, delays in reforming state-owned media; and intimidation and attacks on journalists followed by impunity for the perpetrators. On the other hand, public criticism is growing, albeit slowly, including demands for more transparent and unbiased journalism.”

In Russia authorities are taking increasingly extreme legal and policy measures against freedom of expression, according to a PEN/Free Word Association report “Russia’s Strident Stifling of Free Speech.”

No writers are in prison in Ukraine, but in the Crimea, which Russia annexed in 2014, filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, an opponent of annexation, was arrested and is now serving a 20-year sentence inside a Russian prison on terrorism charges he denies. At PEN’s Assembly, delegates remembered Pavel Sheremet with an Empty Chair. A Belarusian-born Russian journalist and free speech advocate, Sheremet wrote for an independent news website and hosted a radio show where he reported and commented on political developments in Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. He died in a car bomb explosion in Kiev July, 2016. Shortly before he was assassinated, he’d written about corruption among law enforcement in Belarus, Ukraine and propagandists in Russia. His murder remains unsolved.

Resolutions at the Congress also addressed writers imprisoned in Turkey, China, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, and Eritrea and killings in Mexico, Russia, Venezuela, Bangladesh and India. Concerns about increasing censorship in Hungary, Poland, India, Turkey, and Spain were acted on as was the restriction of linguistic rights for Kurdish writers in Turkey, Hungarians in Ukraine and Uyghurs in China.

Expressing concern about the abuse of Interpol’s Red Notice system by some member states “in order to repress freedom of expression or to persecute members of political opposition beyond their borders”, PEN called on the Council of Europe “to refrain from carrying out arrests…when they have serious concerns that the notice in question could be abusive.”

PEN expanded Article 3 of its Charter for the first time since the document’s inception over 90 years ago. The Assembly voted new language which would include a wider mandate, reaching beyond just opposing hatreds of race, class and nations to include by extension gender, religion and other categories of identity. Article 3 of PEN’s Charter, which can be linked to here, now reads: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

PEN also passed a Women’s Manifesto noting “the use of culture, religion and tradition as the defense for keeping women silent as well as the way in which violence against women is a form of censorship needs to be both acknowledged and addressed.”

At the Opening Ceremony author of East West Street Philippe Sands, whose grandfather was born in Lviv, narrated the origins of international human rights law and the concepts “crimes against humanity” and “genocide.” These legal frameworks were developed by two lawyers who passed through the very university where the delegates sat. The legal teams prosecuting at the Nuremberg trials after World War II used these frameworks to secure convictions, including the conviction of Hans Frank, Hitler’s lawyer who governed the area around Lviv and sent over 100,000 Jews to concentration camps and death.

“The Foundations of human rights law came from here,” Sands said. “Every individual has rights under international law.” The lawyers Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin studied at the university at different times and never met. One escaped to Austria then England, the other to America. Lauterpacht protected the rights of the individual with the concept he developed of “crimes against humanity” and Lemkin protected the group with the legal construct for “genocide.” Both men were on the legal teams that successfully secured convictions at Nuremberg.

“No organization in the world knows better than PEN the need to protect individuals and to protect others,” Sands concluded.

Jennifer Clement, PEN International President

Andrei Kurkov from Ukranian PEN and Carles Torner, Executive Director PEN International

At the closing ceremony author David Patrikarakos focused on the current situation as the 21st century unfolds and addressed “Fact, Fiction and Politics in a Post Truth Age.” He told the story of Vitali, who became a troll for the Russian state working at a Troll farm. “When Vitali went to the Troll farm, he had enlisted in the Russian Army; he just didn’t wear a uniform. He and others became their own army with a virtual information war, and it is effective,” said Patrikarakos.

As an unemployed journalist, Vitali developed propaganda, rewriting reports, doctoring news accounts to enhance Russia’s position then distributed these on social media, along with fake news, fake pictures and memes to a wide audience, all relating to Russia’s assault on the Crimea. According to Patrikarakos (Nuclear Iran: The Birth of an Atomic State), who has also written for the New York Times, Financial Times, Guardian, and Wall Street Journal, the Russian state spent $250 million to sow discord in its battle for Crimea.

In the Troll farm where Vitali and other journalists worked, the first floor focused on distorting news reports and circulating them. On the second floor people worked through social media, posting memes and making up ads; on the third floor bloggers wrote about how life was better in Russian and bad for Russians in the Ukraine and on the fourth floor, people posted comments on other sites.

According to Patrikarakos and his sources, there was a bag of sim cards to request new accounts, and people were encouraged to make the accounts in the names of females because women were more likely to be believed. “The first goal was to shore up and get true believers, to give a narrative and sow as much confusion on reality as possible,” Patrikarakos said.

After three months Vitali told his boss he wanted to quit. He wrote an expose of the Troll farm. When it came out, he received threats such as “Don’t you know you can get punched in the face.”

“As I went through towns of Eastern Ukraine, content had seeped into walls,” said Patrikarakos. “In Eastern Ukraine, Putin’s nervous system is on display. There is belief in fake news—that Ukrainians want to kill Russian speakers. Social media is supposed to connect us but it has also shattered unity and divided people; it sets people at loggerheads. The news that young people get depends on who they follow. We all follow who we like, and so prejudice is reaffirmed. Facts are less important than narratives. The new word in 2016 from the Oxford dictionary was ‘post-truth’ which is finding linguistic footing. The goal of many is not to trust truth but to subvert truth,” he concluded.

What can we do to counter this trend? Patrikarakos advised:

- Go out of your way to see people who don’t think like you.

- Go directly to the source of information and go to the news.

- Read those you don’t agree with.

- Read books. (Patrikarakos’ new book is More Than 140 Characters)

- Mistrust the mob.

- Beware of Click bait.

- Click off.