Posts Tagged ‘Lucina Kathmann’

PEN Journey 42: From Copenhagen to Dakar to Guadalajara and in Between

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Royal Danish Library extension in Copenhagen, dubbed the Black Diamond (Photo by © User:Colin / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66870365)

Arriving in Copenhagen in early September 2006, I walked along the waterfront, dodged bicycles and shared coffee and conversation with longtime colleague Niels Barfoed, former President of Danish PEN who had briefly succeeded me as Writers in Prison Chair and was an eminent Danish journalist and writer. We met at the new waterfront extension of the Royal Danish Library, dubbed the Black Diamond because of its imposing black granite cladding and irregular angles. Niels would be moderating a public meeting on Freedom of Expression in the Arab World.

PEN International’s base was broadening in the Middle East and in Africa, both regions where active centers for writers were fragile, but potentially important havens. Danish PEN was hosting a conference with a dozen writers from the Arab-speaking world, including representatives from Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, Palestinian PEN, Tunisia, Lebanon and invited writers from Iraq and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), along with Danish and Norwegian PEN members and International PEN represented by Centers Coordinator Peter Firkin and myself.

The Copenhagen conference had been initiated in part as a response to the Danish cartoons controversy earlier in the year and also as an opportunity to develop PEN’s work and presence in the Middle East. PEN had a few centers in the region and interest from writers in Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, and Bahrain to form additional PEN centers and a desire to revive PEN Lebanon. Developing PEN centers in these areas was challenging given the politics and conflicts on the ground.

Ekbal Baraka, President Egyptian PEN (left) and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, PEN International Secretary (right) meeting in Cairo, 2006

The Copenhagen meetings explored common fields of interest among Western and Arab writers, networking among Arab writers and ways in which PEN could assist. Women writers in the Arab world had particular challenges, a discussion led by Egyptian PEN President Ekbal Baraka. Ekbal later became Chair of PEN International’s Women Writers Committee. Algerian PEN and International PEN board member Mohamed Magani offered to host a subsequent meeting in Algiers the following fall, along with a conference on translation. A public event in the evening showcased the work of the visiting writers.

On the final day the public conference on Freedom of Expression in the Arab World moderated by Niels included discussions on Networking in the Cause for Freedom of Media and Opinion and featured renowned Tunisian journalist and human rights campaigner Sihem Bensedrine. A discussion on Access to Information: Implications to Development was addressed by Jordanian journalist Daoud Kuttab and Danish columnist and Danish PEN President Anders Jerichow. Lebanese Writer Elias Khoury and Egyptian journalist and commentator Mona Eltahawy concluded the conference in a discussion on Publication and Powerplay in the Middle East.

The days together resulted in a loose network of these and other Arab writers and eventually led to the opening of additional PEN centers and work in the Middle East. PEN currently has Bahrain, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestinian centers as well as the Egyptian, Algerian and Moroccan Centers.

******

Anna Politkovskaya, Russian journalist assassinated, 2006

A few weeks after the Copenhagen conference, my phone rang early on Saturday morning October 7, 2006 at my home in Washington, DC. Sara Whyatt, PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee Director, was on the line. She called to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya, Russian journalist, PEN member who’d visited PEN Congresses and meetings, who’d worked for years reporting on Chechnya—had been assassinated. The report was that Anna had been shot that morning in the elevator of her apartment building in Moscow.

For seven years Anna had been one of the few reporting on the war in Chechnya despite intimidation and violence. She had been arrested by the Russian military and suffered a mock execution; she’d been poisoned while flying from Moscow to the Beslan school hostage crisis and had to turn back to get medical treatment. She had survived many dangerous encounters. But now she had been killed.

The killing of Anna Politkovskaya swept through the news media around the world as well as through the PEN world. We were stunned and deeply saddened and then began our protests and calls for investigation, along with human rights organizations worldwide. PEN honored Anna at its subsequent Congress and meetings and annually held an Anna Politkovskaya lecture on the anniversary of her death to commemorate her fortitude and inspiration.

The work in PEN was a helix of hope and pain and sorrow and hope again.

******

Dakar, Senegal, venue for PEN’s upcoming 73rd World International Congress in 2007

At the end of November Senegalese PEN hosted a meeting with African centers engaged with the planning of PEN’s 73rd Congress to be held in 2007 in Dakar. The meeting included representatives from Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Guinea, Senegal, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Ghana. It was standard practice for International PEN to visit the site of an upcoming Congress to review logistics and budgets and programs in advance, to assist and assure the Congress ran smoothly. The 73rd Congress in Dakar would be only the second time a PEN Center in Africa had hosted a World Congress. In addition to reviewing the facilities at the Meridien hotel by the ocean, the delegation met with the Minister at the Ministry of Culture and Classified Historical Heritage which was supporting the Congress.

At that meeting and throughout the Congress to come, I offered the sentiment I had drafted and memorized in French and still endorse:

“Il n’y a que quelques autres pays dans le monde ou l’ecrivain est plus honore qu’au Senegal.

“There are few countries in the world where the writer is more honored than in Senegal.”

Because Senegal’s founding President Leopold Senghor had been a poet and writer of global distinction, also a Vice President of International PEN, Senegal celebrated literature. “As a national leader, Leopold Senghor left a rich heritage and respect for African culture and writing which we hope to honor by International PEN’s upcoming Congress in Dakar,” I told the Minister.

Karen Efford, PEN Program Officer, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, PEN International Secretary, and Caroline McCormick, PEN International Executive Director, meeting in Dakar. Senegalese PEN members organizing PEN 73rd World Congress included Abdoulaye Racine Senghor, Abdoulaye Fode Ndione, Mamadou Diop Traoré, Seydi Sow, Mbaye Gana Kehe, Alioune Badara Beye, Elie-Charles Moreau, Silcarneyni Gueye, Aissatou Diop

Senegalese PEN hosted our working meetings at its headquarters where the focus was also on regional development. International PEN’s Executive Director Caroline McCormick and Program Officer Karen Efford led a “mapping” or gathering of information with each center on its activities and membership and needs in order to determine how PEN International could assist, especially with fundraising. The Centers also participated in the discussions on the programs and facilities for the July 2007 Congress.

After hours of meetings, we all went to dinner together at the local restaurant. I don’t remember the food, except there were generous plates family style. I remember the atmosphere—the bright blues and reds and yellows in the restaurant, the music, and the laughter after a long day concentrating on budgets, logistics, and translations. The planning meetings were work but also fun with friendships among the writers from the PAN Africa Network with whom I had met on numerous occasions over the past few years.

In my three years as International Secretary, I was impressed by the care of all the host centers for Congresses. The Congress in Senegal would be my last as an officer of International PEN, except for the privilege of attending as a Vice President in the years to come. The operational work and responsibility would be passed on. I had determined not to stand for a second term. I had other responsibilities that had been put on hold for three years, and I had learned it was better to leave a position when everyone wanted you to stay, than to stay too long when people were waiting for you to leave. I needed to return to being a writer and to my family and to the other organizational work I did. So Senegal would be a farewell of sorts for me. It would prove to be a grand occasion, but I am getting ahead of myself…

******

“Does Freedom of Expression Have a Limit?” “Hospitality without Borders.”—those two panels I participated in and moderated at the 2006 Gothenburg Book Fair, Scandinavia’s largest. The International Publishers Association (IPA) and International PEN had been collaborators in selecting the Fair’s theme of Freedom of Expression that year. The Book Fair reflected the Freedom of Expression theme in many of its over 2000 events for the 100,000 visitors. PEN and IPA, along with the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN), had an exhibit with a stage where events and seminars took place.

For me, it was a special pleasure to attend the Fair in Sweden where my mentor and predecessor as Writers in Prison Chair Thomas von Vegesack was a respected and now retired publisher. Thomas attended the Book Fair. I noted in my remarks that it was from Thomas I’d learned the difference between having principles and simply talking about principles. Thomas didn’t like “principles,” which meant he didn’t like paradigms of abstractions. Our role—PEN’s role—was pragmatic. It was to help writers in trouble, to be in touch with them and their families so the isolation of imprisonment was broken, to give them support and most of all to figure out where the access was within our PEN centers and within our larger freedom of expression community to pressure governments to spring open the prison doors and also to get protection for writers under death threats. (It was two weeks after the Gothenburg Book Fair that Anna Politkovskaya was assassinated.)

The world had changed since the days Thomas and I had been chair of WiPC. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s we had all been hopeful that the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of the totalitarian governments would ease the situation for writers worldwide, but there were now as many writers as ever under threat. PEN’s casebook listed over 1000. There were more non-state actors. There was also a level of global communication that was only budding in 1993 when Thomas handed over the reins to me. There were new bad guys, and many of the good guys were not as good as they once were. We were in a world where freedom of expression was no longer accepted as an unqualified value.

Yet “the world is still changed by ideas and books, and writers who write them are still the main vehicle for ideas,” I concluded my opening talk.

On the panel “Does Freedom of Expression Have a Limit?” we had no easy answer. We asked if there was a personal and public responsibility to tell the truth, or at least not to lie. And who determined a lie? The responsibility of the writer was to try to find and tell the truth even if truth seemed relative at times. The question arose, who sets the limits on freedom of expression? The State? Society at large? What were those limits and penalties and were they set by fear of attack or violence or censorship?

It was generally agreed that calls for violence such as the killing of another human being set a limit on freedom of expression, especially when this call came from someone who had the power of the state to exercise the threat. An example was the fatwa on Salman Rushdie. The limit should not be on Rushdie but on the Ayatollah and the state that issued the fatwa calling for his death.

Hate speech had a limit when it urged violence as in the case of Radio Rwanda during the genocide against the Tutsis or certain broadcasts during the Balkans wars.

PEN’s Charter contained the elements of the dialectic upon which free societies were based, both the respect for other cultures in an effort to dispel race, class and national hatreds and also a commitment to protect the free and unhampered transmission of thought and ideas.

“And since freedom implies voluntary restraint, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends,” the PEN Charter concluded.

Democracies flourish only when an exchange of competing, even contradictory, ideas can occur in a battle of ideas, the panel concluded.

Novelist Moris Farhi, former WiPC Chair and PEN Vice President/English PEN

The panel “Hospitality Without Borders,” co-sponsored by ICORN, featured Orhan Pamuk, the Turkish novelist who a month later won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and Moris Farhi, also Turkish but long resident in the UK and member of English PEN. Moris had followed me as Chair of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee after Niels Barfoed’s brief tenure.

Novelist Orhan Pamuk (Photo credit: © Elena Seibert)

The previous year, Orhan had faced charges of “insulting the Turkish Army and Turkishness” because of his statement in a Swiss newspaper regarding the Armenian genocide and massacre of a million Armenians and 30,000 Kurds in Anatolia in 1919. On the panel Orhan noted how valuable it was for a persecuted writer in his home to know about the possibility of finding refuge in a safe city, even if he didn’t take advantage or was unable to leave his present situation at the time.

Moris, who’d also chaired English PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, talked about the challenges facing the host city and the community receiving a guest writer. He focused on how to make sure the writer didn’t just disappear from the literary community and the need to focus on translation and publishing strategies for the writer. It was important to help the writer establish new foundations and relationships in a new city.

I recalled the situation of Bangladeshi novelist Taslima Nasreen who had faced death threats and was given asylum in Sweden and awarded the Tucholsky prize. Taslima Nasreen’s was one of the more dramatic cases in my PEN history as she was whisked out of Dhaka in the dark of night and brought to Stockholm by Swedish PEN. That had turned out to be just one stop on a difficult journey into exile.

******

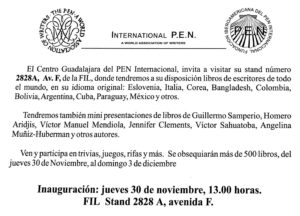

At the end of 2006, PEN Guadalajara, San Miguel PEN and the Ibero-American Foundation of PEN established a presence for the first time at the 20th Guadalajara Book Fair. The Guadalajara Book Fair was considered the most important publishing event in the Spanish-speaking world, hosting 450,000 visitors and 15,000 book professionals from over 40 countries. Officials of the Guadalajara Book Fair were eager to have a relationship with PEN in order to collaborate and “create and guarantee space in which literature of different languages cohabit supporting the freedom of opinion with words as vehicle of understanding between different nations and cultures,” according to the Coordinator of the Festival events.

At the end of 2006, PEN Guadalajara, San Miguel PEN and the Ibero-American Foundation of PEN established a presence for the first time at the 20th Guadalajara Book Fair. The Guadalajara Book Fair was considered the most important publishing event in the Spanish-speaking world, hosting 450,000 visitors and 15,000 book professionals from over 40 countries. Officials of the Guadalajara Book Fair were eager to have a relationship with PEN in order to collaborate and “create and guarantee space in which literature of different languages cohabit supporting the freedom of opinion with words as vehicle of understanding between different nations and cultures,” according to the Coordinator of the Festival events.

International PEN aspired to have a more robust presence at book fairs globally, but did not yet have the budget or staff. However International PEN supported centers’ activities at book fairs such as at Frankfurt, Gothenburg, and now Guadalajara. I visited the Guadalajara Book Fair as part of this initiative.

PEN Guadalajara and San Miguel and the Ibero-American Foundation of PEN hosted a stand at the Book Fair and offered readings and presentations of books and displayed hundreds of books from PEN members and PEN centers around the globe. On the Book Fair’s program two eminent PEN members, Vice President Nadine Gordimer and former PEN International President Mario Vargas Llosa were featured. Nadine Gordimer participated in a Literary Salon and later had dinner with PEN members. I have no notes from that dinner, but I have fond memories of the outside restaurant in the evening and the hospitality of Guadalajara and San Miguel PEN and the graciousness of Nadine Gordimer.

Photo Left: Meeting at 2006 Guadalajara Book Fair: María Elena Ruiz Cruz, Víctor Sahuatoba, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Lucina Kathmann, Luis Mario Cerda, Martha Cerda, Moisés Zamora. Photo Right: At dinner: Moisés Zamora, Nadine Gordimer, Martha Cerda, and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Martha Cerda, President of Guadalajara PEN, PEN Vice President Lucina Kathmann of San Miguel PEN and I met with Book Fair officials and assured that PEN would have a presence and partnership with the Guadalajara Book Fair in the years to come through its Latin American centers.

The visit to Guadalajara also offered the opportunity to meet with members from several Latin American PEN centers in a preliminary focus on the region and on the “mapping” International PEN would undertake of resources, programs and needs of the Latin American PEN centers before the 2008 Congress in the region.

******

At the end of 2006 PEN’s long time staff member Jane Spender retired. Jane had worked with Peter Day on the PEN International Magazine as an editor; she’d been administrative assistant to the Administrative Secretary Elizabeth Paterson and then became the Administrative Director when Elisabeth retired. She had taken on the role of International PEN Program Director when PEN hired an Executive Director. We all relied on Jane’s intelligence, good humor and patience. Jane and I had spent hours—too many hours we both agreed—toiling over just the right word on several documents. I was especially going to miss working with Jane; I have kept the friendship to this day. To celebrate the past and send her off with good wishes for the future, we surprised her by giving her a bicycle which I rode across the office and presented to her. Friends from International PEN and English PEN all gathered in PEN’s new offices on High Holborn. PEN is about people, and Jane was one of the stalwart ones.

Jane Spender retirement party at PEN offices, 2006. L to R: Sara Whyatt, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Jane Spender, Caroline McCormack, Karen Efford, Terry Carlbom, Ursula Setzer, Josephine Pullen-Thompson, Francis King, Peter Day, Gilly Vincent, Jane Spender, Nawal, Karen Efford, Elizabeth Paterson

Next Installment: PEN Journey 43: Turkey and China—One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward

PEN Journey 33: Senegal and Jamaica: PEN’s Reach to Old and New Centers

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

A few days before I flew out to Dakar, Senegal for a PEN conference in November 2004, my youngest son, a Marine in Iraq, called and told my husband and me that we would not hear from him for a while. We knew, without being told, that the U.S. and British troops were likely about to return to Fallujah, the center of the insurgency. Civilians there had been advised to get out of the city, and they were leaving.

On the opening day of the PEN conference in Dakar, November 7, 2004, the battle for Fallujah began. The headlines in the newspapers in Dakar were about the civil war raging in neighboring Ivory Coast so I was not reading about Iraq during the five-day PEN Africa meeting. In 2004 there were no iPhones or phone news feeds and rare coverage of the Middle East was on the evening news. I was quietly attentive each day and prayerful and focused on PEN’s work.

I have modest notes from the first PAN Africa conference, but I have some of my most vivid memories, most particularly of the people I met and of my first trip to Gorée Island just off the Senegalese coast opposite Dakar, a place of its own historic upheaval. Gorée Island was the site of the largest slave-trading center on the African coast from the 15th to the 19th century, ruled successively by the Portuguese, Dutch, English and French. The dungeons and portals to the sea where men and women and children were sent out in chains still stood along with the stucco houses of former slave traders.

Gorée Island, site of slave trading in 15-19th centuries, off coast of Dakar, Senegal

A tall Gambian doctoral student assisting Senegalese PEN guided a few of us around Gorée. Fluent in French, English and Spanish, he was writing a doctoral thesis on the secrets of history and myth in the epic of Kaabu according to Mandingo oral traditions—clearly a future PEN member. Thoughtful, knowledgeable, he spent the day sharing history. During and after the Dakar meetings, our paths crossed in subsequent PEN conferences and congresses, and we know each other still. Dr. Mamadou Tangara earned his doctorate at the University of Limoges in France shortly after and eventually became the Gambian Permanent Representative to the United Nations. During Gambia’s constitutional crisis in 2016-17, he and other diplomats called for the president to step down peacefully; he was dismissed, but when power changed hands a few months later, he was reappointed as Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Gambia. The friendship with Mamadou Tangara remains and is one of my many valued friendships from PEN.

Mamadou Tangara (Gambia) and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary) on Gorée Island at PEN’s 2004 Dakar conference

Mamadou’s mentor at the time was an older Gambian journalist and editor Deyda Hydara, who joined PEN members from more than a dozen African centers in this conference to prepare for PEN’s first PAN African World Congress in Senegal in 2007. The Congress would be PEN’s first in Africa since the 1967 Congress in the Ivory Coast when American playwright Arthur Miller was International PEN President. Though the Gambia didn’t yet have a PEN Center, Deyda was planning on starting one. At the time Deyda Hydara was co-founder and primary editor of The Point, a major independent Gambian newspaper. He was also correspondent for AFP News Agency and Reporters Without Borders and was an advocate for press freedom and a critic of his government’s hostility to the media.

A month after PEN’s Dakar conference, the Gambian government passed a bill allowing prison terms for defamation and another bill requiring newspaper owners to purchase expensive operating licenses and register their homes as security. Deyda Hydara announced his intent to challenge these laws. Two days later on December 16, 2004 Deyda Hydara was assassinated on his way home from work. To this day his murder remains unsolved. The following year Deyda Hydara won PEN America’s Freedom to Write Award posthumously and later the Hero of African Journalism Award of the African Editors Forum.

PAN Africa meeting at Senegal PEN offices. PEN L to R: Remi Raji (Nigerian PEN), Mamadou Tangara (Gambia), Mike Butscher (Sierra Leone PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman,( PEN International Secretary) and Senegal PEN assistants

Deyda Hydara was a dynamic voice for writers at the PEN Dakar conference and for the need of PEN’s African centers to work together against repressive press laws.

The theme of the Dakar meeting—“New Partnership for African Development and Culture”—involved coordinating work among PEN’s African centers, including the nomination of a candidate for International PEN’s board at the 2005 Congress in Bled, Slovenia, assistance to dormant African centers and support for creating new African centers. (There are now more than 25 PEN centers in Africa.) Several African PEN centers also committed to working together in fundraising for projects. Remi Raji of Nigerian PEN took on the role of PAN coordinator, and Mike Butscher, executive secretary of Sierra Leone PEN, was the administrator.

PAN (PEN African Network) was relatively new. In 2001 Dr. Vincent Magombe, a Ugandan journalist and member of PEN’s African Writers Abroad Center and member of PEN’s first International Board and Terry Carlbom, PEN’s International Secretary, had taken a trip to visit many PEN African centers in order to promote activity and develop greater participation in Africa. At the 2003 Mexico Congress members from seven of PEN’s African centers met to launch the PEN African Network (PAN). At the 2004 Congress in Norway representatives from twelve African centers came together for a PAN meeting. By Dakar PAN had grown to over a dozen of PEN’s African centers who agreed to help plan the 2007 World Congress in Dakar.

The implementation and heavy lifting for the Congress would depend on PEN Senegal, one of the oldest and best organized of PEN’s centers in Africa. Senegalese PEN had offices, a small theater and even housing for visiting writers, administered by its General Secretary, poet Alioune Badara Bèye. Because the country’s first President (1960-1980) Leopold Sédar Senghor was himself a renowned poet and a Vice President of International PEN, Senegal had a long tradition of support for literature that was unparalleled in most countries.

The Dakar PAN conference opened on the International Day of the African Writer and was coordinated with the Senegalese Writers’ Association and presided over the by the Minister for Culture. The ceremonies included a literary evening along with traditional Senegalese instrumental ensembles and dance.

The planning work for the 2007 Congress got underway the following day in a large meeting room in Senegal PEN’s writers’ compound. As International Secretary, I addressed the gathering and shared a 1922 news report about PEN that began: Le Coeur n’a pas de pays. (The heart has no country) then continued: “Today when many are claiming a clash of civilizations and fear across borders is rising, PEN can continue to demonstrate international fellowship through its literary programs, its work on behalf of imperiled writers, its support of writing in all languages and cultures, its assistance to writers in exile and its development of new centers, particularly in Africa. PEN’s strength is its members, and it is a pleasure to be here with committed writers from some of PEN’s strongest and also PEN’s emerging African centers.”

International Day of the African Writer and PEN’s PAN Africa conference at Senegal PEN. Participants, including far left Alioune Badara Bèye, (General Secretary, Senegal PEN), Kjell Olaf (Norweigan PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary/American PEN), Femi Osofisan (Nigerian PEN), Terry Carlbom (Swedish PEN), Senegal Minister of Culture, Deyda Hydara (Gambia), Mike Butscher (Sierra Leone PEN) and other PEN members and officials.

Given the conflict next door in the Ivory Coast and in Iraq, Afghanistan and other areas of the world, it seemed especially important to have these positive actions of fellowship growing. While the PAN conference was serious in purpose, it was also full of comradery. I chaired one session and remember looking out at the table of more than a dozen men and only one woman besides myself. I suggested at PEN’s follow-up conference in Ghana next spring, the centers include their women members. The men looked around the table as though only now noting the imbalance. I smiled. The other woman at the conference Koumanthio Zeinab Diallo from Guinea spoke French, and when the translator repeated my words to her in French, she smiled. C’est vrai! and nodded her approval.

Zeinab Diallo (Guinea PEN) and Deyda Hydara (Gambia) at 2004 PEN PAN Conference in Dakar, Senegal.

Since I had taken on the position of International Secretary, I’d been studying French to get to a passable conversational level. It turned out Zeinab was studying English with the same goal. Mamadou Tangara set up a competition between us which he judged every time the three of us saw each other over the months and years ahead at PEN meetings. Even with our salad of language, Zeinab and I communicated and often laughed together though I don’t think either of us achieved the fluency we wanted. A poet, Zeinab wrote in Pular as well as French. She also worked as an Agricultural Engineer and was a development consultant for the UN Development Programme.

Senegal PEN members including General Secretary Alioune Bedara Bèye presenting tribute posthumously for Senegal writer and member Fatou Ndiaye Sow.

At the PAN conference Senegalese PEN presented an award and tribute to its member Fatou Ndiaye Sow who had passed away just the month before while attending a meeting abroad. A poet, teacher and children’s writer, Fatou had been a friend to many of us and was an early member of PEN International’s Women’s Committee. I read a tribute to Fatou by Lucina Kathmann, a close friend of hers and early chair of PEN’s Women’s Committee.

When I took on the role of International Secretary a few months before, there was already a full agenda underway, and I was grateful to Terry Carlbom, my predecessor, and to Jane Spender, the Administrative Director; Terry also attended the Dakar conference. The next three PEN Congresses were lined up to be developed—Bled, Slovenia in 2005, Berlin, Germany in 2006, and Dakar, Senegal in 2007. Each of these would be hosted by experienced PEN centers so while much work was yet to be done and funds raised for these Congresses and for other activities ahead, solid groundwork had been laid.

A new initiative in those early days as International Secretary was to revive and develop PEN’s presence in the Caribbean. The request originated with the UNESCO representative in Jamaica who was himself a writer. A proposal to explore the possibility was developed in partnership with Canadian PEN’s Executive Director Isobel Harry, who’d spent time in Jamaica, had known one of its most famous residents, musician Bob Marley, and knew numbers of Caribbean writers living in Toronto, some of whom were members of Canadian PEN.

Historically, the Caribbean had been underrepresented in PEN except for the existing Puerto Rican Center and a Jamaican PEN Center that had been active from 1948 until the early 1980’s but had disbanded in 1987.

Poet/playwright Derek Walcott, winner 1992 Nobel Prize for Literature. (photo credit: Effigie/Leemage/Writer Pictures)

The Caribbean was enjoying a literary renaissance with events like the CARIFESTA (Caribbean Festival of the Arts), the Calabash Literary Festival and with St. Lucia’s Derek Walcott winning the Nobel Prize for Literature.

In early December, 2004 Isobel and I traveled to Jamaica to meet with writers, professors and UNESCO to determine who and how a PEN center might be launched. PEN Canada had an ongoing relationship with Caribbean writers as did Quebecois PEN, which was working with Haitian writers to help develop a PEN center there. Haitian writer Georges Anglade, who lived part time in Montreal and was the founding President of Haitian PEN, had recently attended the PEN Congress in Tromso, Norway. (Ref Haitian Farewell)

At the minimum, to form a new PEN center at least 20 qualified writers have to come together, sign and agree to commit to the Charter of PEN and propose a reason and program for their center.

Isobel and I flew to Kingston, arriving from the early blasts of winter into the Jamaican sun. It was not hard duty. Over the course of three days we met with a dozen writers, professors, festival organizers, human rights activists and the UNESCO representative Alwin Bully, who was also Chair of the CARIFESTA Task Force. UNESCO’s mandate was to integrate the Caribbean, and Alwin Bully saw PEN as a unifying organization and thought a PEN Center might include writers from many of the Caribbean islands.

Isobel and I met with him several times as well as with the founders and producer of the Calabash International Festival and with journalists from the Jamaica Observer, professors at the University of the West Indies, chief curator of the National Art Gallery, the Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, and the former head of the Human Rights Council. All were enthusiastic about the possibility of a PEN Center.

Colin Channer and Kwame Dawes, founders of the Calabash International Literary Festival, offered to host a planning meeting before the next festival. UNESCO offered to fund the workshop/planning session and include writers from many Caribbean countries. The Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, which had three main campuses in Barbados, Trinidad and Jamaica, said the university could perhaps provide institutional support. Professor Carolyn Cooper of the Department of Literature in English and board member of the Calabash Festival and a writer said she’d be glad to be a founding member and help recruit so that the PEN center had an inclusive group of all types of writers.

L to r: Novelist Colin Channer (photo credit: Allison Evans), poet Kwame Dawes (photo credit: Andre Lambertson), founders of Calabash International Literary Festival, and Professor Carolyn Cooper of the University of the West Indies (photo credit: Isobel Harry)

Florizelle O’Connor, the former head of the Human Rights Council and member of the UN Sub Commission on Human Rights was also enthusiastic about a PEN center. She felt the right to freedom of expression and access to information were issues that needed protecting in Jamaica and the Caribbean.

Novelist Marlon James, 2015 Man Booker Prize winner

Questions arose on where a Caribbean PEN center would be located—Jamaica, Trinidad, other? Other writers, including journalists from the Jamaica Observer, emphasized that a center would need equal representation of writers and journalists and no one constituency should be keeper of the PEN flame.

Writers who lived part time in Jamaica and part time in Toronto, New York, London and elsewhere noted that most writers far from home sought ways to keep strong the bonds and identity with the Caribbean; a PEN center could help. Each interview resulted in a list of at least four to six more people to speak with, including later Marlon James, who would eventually win the Man Booker Prize.

At the end of our three-day trip circling Kingston aglow with red, green and gold Christmas lights and swaying palm trees, we concluded a PEN Center would happen. At its best it could bring together writers, journalists and creative people in the islands and provide further access to each other, broaden access to the world of literature and enable writers to present a collective voice for greater impact on issues such as freedom of expression.

The writers would have to decide the questions ahead—who would be eligible, the balance of journalists and creative writers and the diasporic writers whose numbers might exceed the local writers. A large unresolved question was whether the PEN center would be Jamaican PEN as in the past or a pan-Caribbean PEN.

As we left the island to return to our winter, it was agreed the discussions would continue among the writers, including those Caribbean writers in New York, Toronto and London and with UNESCO. A workshop/planning meeting in association with the Calabash Festival and the University would be held, probably in May 2005. Isobel would return.

In 2006 the Jamaica Center was voted into PEN at the Berlin congress and joined over 135 PEN centers worldwide.**

Next Installment: PEN Journey 34: Diyarbakir and Beyond—Finding Byways for Peace

——————-

*Current African PEN Centers: Afar, Afrikaans, Algerian, Egyptian, Eritrean in Exile, Ethiopian, Gambian, Guinea-Bissau, Guinean, Ivory Coast, Kenyan, Liberian, Malawian, Malaysian, Mali, Mauritania, Moroccan, Nigerian, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somali-Speaking, South African, Togo, Tunisian, Ugandan, Zambian, Zimbabwe

**Current Caribbean PEN Centers: Cuban, Haitian, Jamaican, Puerto Rican