Posts Tagged ‘Taslima Nasrin’

PEN Journey 12: Tolerance on the Horizon?

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

It was a time of hope, the year when Nelson Mandela and Frederik de Klerk joined in free elections in South Africa, when Yasser Arafat, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres shook hands and began to live side by side, when the Irish Republican Army and the Ulster Defense Association laid down their arms after twenty-five years of terrorist conflict. The idea of tolerance quivered in the imagination in 1994 even if the realization of tolerant societies still seemed an imaginative leap.

As theme of the 61st PEN Congress, tolerance also challenged the ethnic, national and religious intolerance that gripped dozens of countries in the last decade of the twentieth century. In retrospect the time was perhaps not so different from times since, but we felt we were standing on an historic threshold. The PEN Congress theme of tolerance expressed this hope and optimism.

Liechtenstein Palace, garden view

Writers from over 75 PEN centers* around the world came together in Prague that fall for literary and working sessions. The Congress was a grand affair with public gatherings in stately ballrooms, including the Liechtenstein Palace, home of the Prague Academy of Music. Writers who had been imprisoned under the old Soviet regime, including Václav Havel, now ran the country.

Guests of honor included novelist and poet Taslima Nasrin, whom PEN had recently helped extract from the threat of death in Bangladesh (see PEN Journey 11). For protection she was driven around in a state car, and because Sara Whyatt, coordinator of the PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), and I agreed to look after her, we at times found ourselves whisked from meeting to meeting with a police escort, not the usual transport at a PEN Congress.

Though PEN had no mechanisms to change societies, to the extent society changed individual by individual, PEN worked for the writer, turning a spotlight on cases of abuse and challenging the laws which legitimized intolerance.

The voice of the individual writer has always been the most compelling testimony. My report to the Assembly of Delegates that year as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee focused on those voices:

“Yes, I can hear birds singing. But they are not my friends. They are too far from me. My best friends are spiders and mantis. They are only living things to watch amusedly in my solitary cell. I live and play with them all day long. This excerpt is from a prisoner ten years into a twenty-year sentence written to his PEN minder.

“The image of the spider recurs in the writings of prisoners. One former prisoner I met shortly after taking over as Chair of this committee had come to London to receive treatment for the torture he’d endured. He told of being handcuffed to a generator outside during monsoon season, of not being allowed to wash, using a bucket as a toilet, his arms and hands wrapped around the generator for weeks. Then he talked about being inside in solitary confinement. ‘I had a chance to observe nature: rats, cockroaches, spiders,’ he recalled. ‘Ah, spiders, they are brilliant!’

“Cuban writer Yndamiro Restano, who was arrested in 1991 and sentenced to ten years in prison for preparing and distributing counter-revolutionary propaganda, has written a poem entitled Prison:

Mother,

Do you know where your poet is?

Well, they have dragged me into a dark,

Narrow, lonely cell,

And do you know why,

Mother?

For not allowing fear to carry me away.

But I am not completely alone,

Mother.

I have got to know a good friend here.

A small spider visits me every day

And spins in the door of my cell.

When the guard comes,

I let it know so it hides away.

And doesn’t get killed.

I want it to live,

Mother,

Because I know that it has inside it

Something that I also possess.

However,

It seems that the guard does not know this.

Mother,

Do you know where your poet is?

Well, they have dragged me to a cold,

Narrow, lonely cell.

And do you know why,

Mother?

Because the poet is the only person

Who never forgets

The meaning of freedom.

“The quality the spider has inside so like the writer is the ability to survive, to weave and to work wherever it is. The more difficult the circumstances, the more ingenious the web it weaves. Scientists are in fact currently studying the unique structure of the spider’s silk which gives it the tensile strength of a steel fiber, yet allows it to stretch and rebound from at least ten times its original length, something no metal or synthetic fiber can do.

“The writer’s silk, his tensile yet flexible fiber, is his imagination. It is the imagination and the life of the mind that allows the writers for whom the Writers in Prison Committee works to survive what are sometimes quite desperate physical conditions. One quality that gives the imagination its greatest flexibility and strength is tolerance, the theme of this Congress. It also is that quality and the ability to imagine and empathize with another’s life that prompts those not in prison or under attack to work on behalf of their fellow writers.

“The work of PEN members and Centers in 1994 has been inspiring even if the situation for the writers has been very difficult in many areas of the world. This past year has witnessed some remarkable moves towards tolerance: in South Africa with the first free elections, in Israel and the West Bank with the Israeli-Palestinian peace accord. The WiPC case load has declined with release of political prisoners in these areas, but writers remain in the line of fire and are still targets of those who are trying to disrupt the peace process.

“The past year over 120 writers have been released from prison. Unfortunately many times that number have been arrested, threatened and killed.

“Religion, ethnic and nationalistic tolerance has led to attacks and detention of writers in every area of the world. Religious intolerance of one kind or another continues to undermine intellectual freedom in Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Mauritius, Sudan, Egypt, Vietnam and Algeria.

“Often religion is used to justify political interests. No place has the confrontation between “religious” and state power been more devastating than in Algeria, where over 25 writers and journalists have been killed and dozens detained in the past two years.

“Ethnic, national and religious intolerance often merge as in the former Yugoslavia and other areas of the Balkans.

“The most brutal outbreak of ethnic intolerance globally this year has been in Rwanda, where over 37 writers and journalists have been killed, most targeted for their ethnic, and thus political background.

“Ethnic conflict, which is also political conflict, currently stirs in Nigeria where Ken Saro Wiwa, advocate for the Ogoni people, is in jail and reportedly tortured and in Kenya where Koigi wa Wamwere exposed “ethnic cleansing” in the Rift Valley and has been detained on charges which carry the death penalty.

“The most difficult country with the largest number of Writers in Prison Committee cases continues to be Turkey where those discussing and debating the Kurdish situation in the Southeast are charged with “disseminating separatist propaganda” under Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law and are imprisoned. Killings and torture are reported by both sides of this conflict. PEN records over 250 cases in Turkey.

“The other country which continues to lead our list with the most main cases is China where over 45 writers, a third of these in Tibet, are imprisoned. Though China has released some prominent dissidents this year, the Chinese authorities have also arrested at least twice as many writers as they have released…”

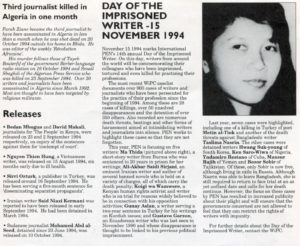

From PEN’s Centre to Centre newsletter October/November, 1994.

The Chair’s report for 1994 notes progress but also shows how little has changed for writers in the past 25 years in many areas of the world such as Turkey and China though there has been progress in Algeria, Rwanda, the Balkans, Nigeria and Kenya. The Day of the Imprisoned Writer campaign in November, 1994, noted in the newsletter above, focused on five writers. Of these Ma Thida was released and eventually started a Myanmar/Burma PEN Center and now serves on the PEN International Board; Koigi wa Wamwere was released and is a celebrated Kenyan writer. Gunay Aslan and Gustavo Garzon, also released, continue to create. Ali-Akbar Sa’idi Sirjani died in Iranian prison under mysterious circumstances in November 25, 1994.

With attention and advocacy, circumstances improve for individual writers, but many writers who are released have to go into exile. At the Prague Congress PEN began to expand its thinking and resources to develop services for exiled writers. (Future blog post.)

A highlight of the 61st Congress was the address by Czech President Václav Havel, fellow writer and playwright whose first play “Garden Party” lampooned the communist system in 1963. In 1969 he was barred from his job as a writer/editor after the suppression of the Prague Spring reforms in 1968, and he was forced to work as a manual laborer. In 1977 he became the spokesman for the Charter 77 dissident group that criticized the communist officials and was given a suspended sentence of 14 months. After publishing in 1978 “Power of the Powerless” which was an analysis of how a totalitarian regime kept power by corrupting and manipulating citizens, he was sentenced to four and a half years in prison for “subversion” against the state. During this time PEN worked actively on his case, pressuring diplomats around the world. Havel was released after three and a half years but then imprisoned again after meeting dissidents and the French President in Prague in 1989. Havel was sentenced to nine months, but widespread protests from home and abroad, many generated by PEN, brought his release in May. In November, 1989 the communist regime fell. In December 1989 Václav Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia, which eventually split. At the time of the PEN Congress he was in his first year as President of the newly independent Czech Republic.

Left to right: Jiří Stránský, President Czech PEN, and Czech President Václav Havel

Abridged speech of Václav Havel to the Opening of the 61st PEN Congress in Prague November 7, 1994:

“Several times in my life I have had the honour of being invited to a world congress of the International PEN Club. But the regime always made it impossible for me to attend. I had to live to the age of fifty-eight, go through a revolution in my country, become the nation’s president, and see the World Congress held in Prague, to be able to participate in this important event for the first time in my life. I am sure you will understand therefore, that this is a very moving moment for me.

“Yes, we live in a remarkable time. It is not just that we now learn, almost instantaneously, about all the deeply shocking atrocities that take place in the world; it is also a time when every local conflict has the potential to divide the international community and become the catalyst for a far wider conflict, one that in many cases is even global. Who among us, for instance, can tell where the present war in Bosnia and Herzegovina may lead, to what tragic confrontation of three spheres of civilization, if the democratic world remains as indifferent to that conflict as it has so far?

“I think that in these matters, writers and intellectuals can and must play a role that only they can fill. They are people whose profession, indeed, whose very vocation is to perceive far more profoundly than others the general context of things, to feel a general sense of responsibility for the world, and to articulate publicly this inner experience.

“To achieve this, they have essentially two instruments available to them.

“The first is the very substance of their work—that is, literature, or simply writing. Deep analysis of the tangled roots of intolerance in our individual and collective unconsciousness and consciousness, a merciless examination of all the frustrations of loneliness, personal inadequacies and the loss of metaphysical certainties that is one of the sources of human aggression—quite simply, a sharp light thrown on the misery of the contemporary human soul—this is, I think, the most important thing writers can do. In any case, there is nothing new in this: they have always done that, and there is no reason why they should not go on doing so…

“But there is another instrument, an instrument that intellectuals sometimes avail themselves of here and there, though not nearly often enough in my opinion. This other instrument is the public activity of intellectuals as citizens, when they engage in politics in the broadest sense of the word. Let us admit that most of us writers feel an essential aversion to politics. We see entering politics as a betrayal of our independence, and we reject it on the grounds that the job of the writer is simply to write. By taking such a position, however, we accept the perverted principle of specialization, according to which some are paid to write about the horrors of the world and human responsibility, and others to deal with those horrors and bear the human responsibility for them. It is the principle of a rather doubtful division of labour: some are here to understand the world and morality, without having to intervene in that world and turn morality into action; others are here to intervene in the world and behave morally without being bound in any way to understand any of it…

“In short, I am convinced that the world of today with so many threats to its civilization and so little capacity to deal with them, is crying out for people who have understood something of that world and know what to do about it to play far more vigorous role in politics. I felt this when I was an independent writer, and my time in politics has only confirmed the rightness of that feeling, because it has showed me how little there is in world politics of the mind-set that makes it possible to look further than the borders of one’s own electoral district and its monetary moods, or beyond the next election.

“I am not suggesting, dear colleagues, that you all become presidents in your own countries, or that each of you go out and start a political party. It would, however, be wonderful if you were to do something else, something less conspicuous, but perhaps more important: that is, if you would gradually begin to create something like a world-wide lobby, a special brotherhood or, if I may use the word, a somewhat conspiratorial mafia whose aim is not just to write marvelous books or occasional manifests, but to have an impact on politics and its human perceptions in a spirit of solidarity, and in a coordinated, deliberate way…”

“Let me conclude with one final plea: do not fail to raise your common voice in defence of our colleague and friend Salman Rushdie, who is still the target of a lethal arrow, and in defence of Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, who is unable to join us here because his government prevented him from coming. I also beg you to express our common solidarity with all Bosnian intellectuals who have been waging a courageous and unequal struggle on the cultural front with the criminal fanaticism of the ethnic cleansers, those living examples of the lengths to which human intolerance can eventually go.”

Next Installment: PEN Journey 13: PEN and the U.N in a Changing World

*Delegates representing 73 PEN Centers attended the 61st Congress, along with observers from three proposed new centers—Malawi, Guadalajara and Iranian Exiles Abroad. All three were elected as new PEN centers at the Congress, along with new centers in Ghana and Kyrgyzstan and a revived Egyptian PEN center.

PEN Journey 11: Death and Its Threat: the Ultimate Censor

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

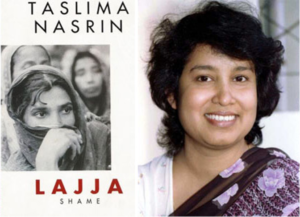

In Bangladesh novelist Taslima Nasrin was in hiding. Death threats had been issued, a price put on her life. On the streets of Dhaka and other cities, crowds threatened to hang her because of her words in a newspaper challenging the Koran and Islamic laws and because of her novel Lajja (Shame) which depicted Muslim atrocities on Hindus after a mosque’s destruction in Ayodhya, India.

The time was summer, 1994. In London Sara Whyatt, PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee Coordinator, and I sat in a Kensington hotel restaurant waiting to meet a man who’d called the office and said he was Taslima’s brother and wanted to talk with us. PEN had been actively working on Taslima’s case for the past year, sending out Rapid Action Alerts, meeting with Bangladeshi government officials in London and in the U.S. and Europe, calling on the government to protect her. The case had gained international attention. Given recent violence around fatwas, including those on Salman Rushdie, we were wary. We didn’t know Taslima had a brother. We spoke with MI5 who advised us to have a spotter for the meeting. We arranged a tell so that if the encounter was not legitimate or we perceived trouble, I would take my sunglasses from the top of my head and set them on the table. The spotter—PEN’s bookkeeper—sat at another table and could quickly summon help. We weren’t certain, but we thought MI5 was also in the hotel.

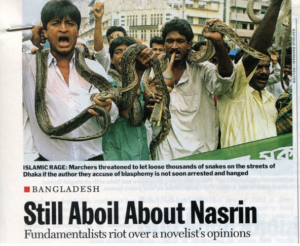

In retrospect the drama around Taslima’s case seems inflated, but during that period of 1993-1994 the situation had escalated to the point that religious leaders were warning that the government would be overthrown if Nasrin was not arrested. In June, 1994 when an arrest warrant was issued, Taslima went into hiding. A nationwide hunt was launched, and snake charmers carrying poisonous snakes marched in Dhaka and warned that thousands of snakes would be let loose if Nasrin was not arrested by June 30.

Time, July 11, 1994. Photo by Rafique Rahman-Reuters

In this atmosphere PEN had received the call from Taslima’s older brother. International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and PEN’s Women’s Committee, in particular its chair Meredith Tax in New York, had been in touch with Taslima and her lawyers, but in the time of faxes, (now fading), inconsistent telephone connections, and no internet between writers, no one had yet confirmed a brother coming through London. This kind of high drama was not PEN’s usual modus operandi. In the years I chaired PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), more than 900 writers threatened, detained, in prison, and killed came across PEN’s desk annually. Approximately a quarter of these were designated main cases which meant PEN had sufficient information to verify the situations and had members to work on the writer’s behalf. However, only a few became global causes like Taslima’s, gathering energy, attention and advocates around the world. This usually happened when the threat of death was credible and immanent and when the circumstances of the writer connected to larger issues.

That day in London, a man in his thirties approached our table. He looked so much like pictures of Taslima that we quickly set aside our suspicions. He worked for an airline and was passing through London. He was able to answer questions and confirm details of the case such as what Taslima had actually said to the newspaper which had misquoted her calling for revision of the Koran. I still have my notes from that meeting. Her brother explained that Taslima had said she wanted to modify Sharia laws, not the Koran. “I want men and women to be equal,” she’d said. She was charged with blasphemy under a law left on the books by the British.

Her brother told us that her lawyer was afraid. The lawyer couldn’t move for bail unless Taslima was present, but if the government didn’t give security for her, they couldn’t take the risk of Taslima coming to court. The government said if Nasrin went to court, anything could happen in court or in jail. In jail she could be killed. Her father’s home had been attacked, and he was now under protection.

Her brother confirmed that Taslima had finally agreed that she needed to leave Bangladesh though she was reluctant. “If I go from Bangladesh, who can write about these poor women?” she asked. And yet she wasn’t able to write anything now, he said, and her life was not safe if she stayed.

Her trial date had been set for Aug. 4. If she didn’t appear, the government would seize her things, including her passport, which they had taken away before but had returned when she resigned her post as a doctor. She was a medical doctor as well as writer.

Her brother’s message to us that day was: “Save my sister!”

Through discussions with her lawyer, with selected PEN members and with the Bangladeshi courts, it was finally arranged that Taslima would turn herself in late in the evening. Bail would be set and met, and in disguise she would leave the court. The president of Swedish PEN flew to Dhaka and accompanied her in a flight to Sweden, where she lived for years in exile.

It was lonely in exile. I met with Taslima in early September 1994, a few weeks after her arrival in Stockholm. I have notes from those meetings. “One day I’ll go back,” she said, “but I don’t know if I could live in my country anymore. I don’t know what will happen. I want to live in Bengal, but they will kill me. I couldn’t take my writing out.”

She explained that she was from a Muslim family with Hindus as her neighbors. “From the beginning I went to their houses, played with them. I know their culture, attitudes. I know their happiness and sorrow from childhood. It is not difficult for me to reach them.” After the violent incidents in Ayodhya, India where Hindu women were raped and their homes looted, she said, “I felt them. I have felt the danger and had to write for them…Why can’t I write a book in reverse, but they feel they should write my book in the case like Lajja…In India, Hindus can’t feel Muslim, and Muslims can’t feel Hindu…In Bengal, Hindu and Muslim live separately…People think men are superior to women. Women always get advice from men. Mothers are always kept quiet. It is not allowed for a mother to give advice to a son.”

London Review of Books, September 8, 1994

At the time and in retrospect at PEN we questioned whether any of our actions escalated the situation for Taslima’s case. This was the Bangladeshi government’s argument, but Amnesty and numerous human rights and freedom of expression organizations also highlighted her situation. Through IFEX, the International Freedom of Expression Exchange of which PEN was a founding member, reports circulated worldwide. The fact was, Taslima Nasrin was in real danger. PEN went into action and helped with her extraction.

In November 1994 Taslima was a special guest at the 61st PEN International Congress in Prague, opened by Vaclav Havel as the keynote speaker. In December that year she received the prestigious Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, given by the European Parliament.

Though Taslima’s case was the most celebrated at the time, there were numbers of other writers and women under threat because of their writing. In a town in Northern Greece Anastasia Karakasidou had received anonymous letters threatening to rape and kill her in front of her children because of her scholarly dissertation on the ethnic Slav population in that region. In Algeria another woman writer stayed in her house afraid even to go out on the street because her words challenged both government and fundamentalists’ violent policies. She had not received a direct death threat, but she was a well-known and recognized writer in a country where more writers had been killed in that past year than in almost any other, including Somalia, Angola and the former Yugoslavia.

Death was the ultimate censor, and the threat of death was its chilling companion. International PEN’s Writers in Prison casebook at the time listed at least 22 countries where writers were under death threats. In four countries the writers had gone into hiding. Death threats also prompted self-censorship for many writers. Most of the threats did not come directly from governments but from individuals who professed to be offended by the writer’s words. The offense, however, was almost always tied to a political or religious position, and the writer’s life became a political, not a moral, consideration.

While issues of communal violence and religious and political Islam differed from the rights of ethnic minorities in Northern Greece or from political probity in Argentina, Guatemala, Peru, Paraguay where PEN listed high numbers of death threats, the common need in all these cases was for the government to protect the writers and take action against those who issued the threats.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 12: Tolerance on the Horizon?

PEN Journey 10: WiPC: Beware of Principles

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

In the summer of 1993 before taking over the Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee I studied hundreds of individual cases on PEN’s list of over 900 cases which was published twice a year. I studied the regions of the world where conflict was rife, where governments were most oppressive and where writers were most threatened. I also used the time to conceive three long term projects because I knew when the job began, there would be less time for long term thinking.

First, I hoped we could gather the many poems and stories from imprisoned writers over the years and get these published into a book. In studying the cases, I came to understand that those who survived harrowing experiences were often those able to keep their imaginations alive and if possible were able to write. “We lived in Paris in our minds,” one prisoner in dire conditions inside the Western Sahara recounted. A book of these writings would celebrate and inspire and could also be used by PEN centers in their work.

Second, I wanted to convene the Writers in Prison Committees from around the world in a conference to strategize our work. PEN’s other standing committees had such meetings outside of the congresses, but WiPC never had. The PEN congresses were often filled with competing programs and those working on WiPC issues were not always the delegates. We needed to gather and plan together for several days.

Finally, I hoped to expand the roster of Writers in Prison Committees in the PEN Centers so that we could increase the number of members working and the number of writers on whose behalf we worked.

WiPC Coordinator Sara Whyatt and researcher Mandy Garner and I agreed on each of these goals. Every two weeks we met in the large airy WiPC office at the top of the Charterhouse Buildings in London or often at the tea shop across the alley. At the end of our strategy sessions we would discuss how to move forward the longer range goals. I learned an important lesson—first, a goal begins with an idea then is realized by having talented, committed people around. For me that began with Sara and Mandy, who set steps in motion. And then each project found a path forward as people arrived into our circle to help accomplish the tasks.

One day a publisher showed up in our office and asked if we had ever considered doing a book of prisoners’ writings. As a matter of fact…We quickly outlined our idea, put together a team with former WiPC coordinator Siobhan Dowd as editor, and a year and a half later in 1996 This Prison Where I Live was on book stands with selections from more than 65 writers who had been imprisoned, many of whose cases PEN had worked on, from Arthur Koestler to Cesar Vallejo, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Jacobo Timerman, Breyten Breytenbach, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Primo Levi, Wole Soyinka, Vaclav Havel, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Nazim Hikmet, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and many others, current and former writers in prison.

From This Prison Where I Live:

You took away all the oceans and all the room.

You gave me my shoe-size with bars around it.

Where did it get you? Nowhere.

You left me my lips, and they shape words, even in silence.

—Osip Mandelstam, former USSR, 1935

When we shared our second hope for a global gathering, Danish PEN offered to host the conference in Helsingor, the home of Hamlet. With representatives of PEN centers on every continent, this first WiPC conference convened in the spring of 1996. The WiPC gathering has been held biennially ever since at locations around the world. (More on this conference in a later post.)

Regarding the third goal, the number of PEN centers with Writers in Prison Committees has grown each year because of PEN members around the globe. Unfortunately, the number of cases of writers threatened, imprisoned or killed has also continued to grow, but individual cases are released.

In that summer preparing to take over the Chair, my predecessor and mentor Thomas von Vegesack gave me advice I found puzzling at first. He invoked: “Beware of principles!” Thomas was an empathetic and principled man so I was perplexed by his counsel, but over the years I’ve come to understand what he meant. He meant that declarations and statements can often keep you from seeing a way forward and from understanding how to work on a case if you get tangled in abstractions.

There are of course principles that govern our work enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These are fundamental, but Thomas was warning that it is important to understand each situation and not let rigidity, a kind of authoritarianism of principles or political correctness limit.

PEN’s Charter itself contains contradictory concepts. The Charter asserts that PEN members should “use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

At the same time the Charter notes that “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong…”

These two ideas of respect and freedom of expression have been challenged more than once, a decade ago in the case of the Danish cartoons. (More on this in a future post.)

Ultimately each PEN member has to resolve the inherent tension. Those from societies with longer democratic traditions are more accustomed to balancing competing ideas; but there are no certain answers. PEN has had lengthy discussions and debates on such questions as “hate speech”—what constitutes it, are there limits to freedom of expression—on slander and libel, holocaust denial, blasphemy.

These challenges for PEN are manifested in individual cases. Early in my tenure as Writers in Prison Chair, one such case blew up quickly, gathering headlines across the globe—the case of Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasrin. Dr. Nasrin (she was a medical doctor turned writer) had written a novel Lajja (Shame) which described the Muslim backlash against Bangladesh’s Hindu minority after the destruction of a mosque. She was also quoted (misquoted, she said) suggesting that the Koran should be revised in favor of women. An arrest warrant was issued for her; demonstrators called for her death, and at one point snake charmers in Dhaka threatened to release their cobras into the streets if she wasn’t executed. PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and PEN’s Women’s Committee took up the case, which had bizarre twists along the way.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 11: Death and Its Threat: The Ultimate Censor