Posts Tagged ‘India’

PEN Journey 11: Death and Its Threat: the Ultimate Censor

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

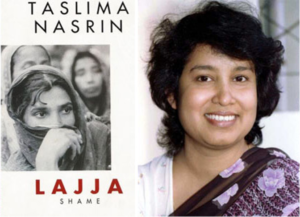

In Bangladesh novelist Taslima Nasrin was in hiding. Death threats had been issued, a price put on her life. On the streets of Dhaka and other cities, crowds threatened to hang her because of her words in a newspaper challenging the Koran and Islamic laws and because of her novel Lajja (Shame) which depicted Muslim atrocities on Hindus after a mosque’s destruction in Ayodhya, India.

The time was summer, 1994. In London Sara Whyatt, PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee Coordinator, and I sat in a Kensington hotel restaurant waiting to meet a man who’d called the office and said he was Taslima’s brother and wanted to talk with us. PEN had been actively working on Taslima’s case for the past year, sending out Rapid Action Alerts, meeting with Bangladeshi government officials in London and in the U.S. and Europe, calling on the government to protect her. The case had gained international attention. Given recent violence around fatwas, including those on Salman Rushdie, we were wary. We didn’t know Taslima had a brother. We spoke with MI5 who advised us to have a spotter for the meeting. We arranged a tell so that if the encounter was not legitimate or we perceived trouble, I would take my sunglasses from the top of my head and set them on the table. The spotter—PEN’s bookkeeper—sat at another table and could quickly summon help. We weren’t certain, but we thought MI5 was also in the hotel.

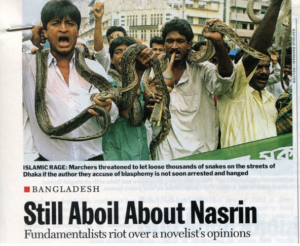

In retrospect the drama around Taslima’s case seems inflated, but during that period of 1993-1994 the situation had escalated to the point that religious leaders were warning that the government would be overthrown if Nasrin was not arrested. In June, 1994 when an arrest warrant was issued, Taslima went into hiding. A nationwide hunt was launched, and snake charmers carrying poisonous snakes marched in Dhaka and warned that thousands of snakes would be let loose if Nasrin was not arrested by June 30.

Time, July 11, 1994. Photo by Rafique Rahman-Reuters

In this atmosphere PEN had received the call from Taslima’s older brother. International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and PEN’s Women’s Committee, in particular its chair Meredith Tax in New York, had been in touch with Taslima and her lawyers, but in the time of faxes, (now fading), inconsistent telephone connections, and no internet between writers, no one had yet confirmed a brother coming through London. This kind of high drama was not PEN’s usual modus operandi. In the years I chaired PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), more than 900 writers threatened, detained, in prison, and killed came across PEN’s desk annually. Approximately a quarter of these were designated main cases which meant PEN had sufficient information to verify the situations and had members to work on the writer’s behalf. However, only a few became global causes like Taslima’s, gathering energy, attention and advocates around the world. This usually happened when the threat of death was credible and immanent and when the circumstances of the writer connected to larger issues.

That day in London, a man in his thirties approached our table. He looked so much like pictures of Taslima that we quickly set aside our suspicions. He worked for an airline and was passing through London. He was able to answer questions and confirm details of the case such as what Taslima had actually said to the newspaper which had misquoted her calling for revision of the Koran. I still have my notes from that meeting. Her brother explained that Taslima had said she wanted to modify Sharia laws, not the Koran. “I want men and women to be equal,” she’d said. She was charged with blasphemy under a law left on the books by the British.

Her brother told us that her lawyer was afraid. The lawyer couldn’t move for bail unless Taslima was present, but if the government didn’t give security for her, they couldn’t take the risk of Taslima coming to court. The government said if Nasrin went to court, anything could happen in court or in jail. In jail she could be killed. Her father’s home had been attacked, and he was now under protection.

Her brother confirmed that Taslima had finally agreed that she needed to leave Bangladesh though she was reluctant. “If I go from Bangladesh, who can write about these poor women?” she asked. And yet she wasn’t able to write anything now, he said, and her life was not safe if she stayed.

Her trial date had been set for Aug. 4. If she didn’t appear, the government would seize her things, including her passport, which they had taken away before but had returned when she resigned her post as a doctor. She was a medical doctor as well as writer.

Her brother’s message to us that day was: “Save my sister!”

Through discussions with her lawyer, with selected PEN members and with the Bangladeshi courts, it was finally arranged that Taslima would turn herself in late in the evening. Bail would be set and met, and in disguise she would leave the court. The president of Swedish PEN flew to Dhaka and accompanied her in a flight to Sweden, where she lived for years in exile.

It was lonely in exile. I met with Taslima in early September 1994, a few weeks after her arrival in Stockholm. I have notes from those meetings. “One day I’ll go back,” she said, “but I don’t know if I could live in my country anymore. I don’t know what will happen. I want to live in Bengal, but they will kill me. I couldn’t take my writing out.”

She explained that she was from a Muslim family with Hindus as her neighbors. “From the beginning I went to their houses, played with them. I know their culture, attitudes. I know their happiness and sorrow from childhood. It is not difficult for me to reach them.” After the violent incidents in Ayodhya, India where Hindu women were raped and their homes looted, she said, “I felt them. I have felt the danger and had to write for them…Why can’t I write a book in reverse, but they feel they should write my book in the case like Lajja…In India, Hindus can’t feel Muslim, and Muslims can’t feel Hindu…In Bengal, Hindu and Muslim live separately…People think men are superior to women. Women always get advice from men. Mothers are always kept quiet. It is not allowed for a mother to give advice to a son.”

London Review of Books, September 8, 1994

At the time and in retrospect at PEN we questioned whether any of our actions escalated the situation for Taslima’s case. This was the Bangladeshi government’s argument, but Amnesty and numerous human rights and freedom of expression organizations also highlighted her situation. Through IFEX, the International Freedom of Expression Exchange of which PEN was a founding member, reports circulated worldwide. The fact was, Taslima Nasrin was in real danger. PEN went into action and helped with her extraction.

In November 1994 Taslima was a special guest at the 61st PEN International Congress in Prague, opened by Vaclav Havel as the keynote speaker. In December that year she received the prestigious Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, given by the European Parliament.

Though Taslima’s case was the most celebrated at the time, there were numbers of other writers and women under threat because of their writing. In a town in Northern Greece Anastasia Karakasidou had received anonymous letters threatening to rape and kill her in front of her children because of her scholarly dissertation on the ethnic Slav population in that region. In Algeria another woman writer stayed in her house afraid even to go out on the street because her words challenged both government and fundamentalists’ violent policies. She had not received a direct death threat, but she was a well-known and recognized writer in a country where more writers had been killed in that past year than in almost any other, including Somalia, Angola and the former Yugoslavia.

Death was the ultimate censor, and the threat of death was its chilling companion. International PEN’s Writers in Prison casebook at the time listed at least 22 countries where writers were under death threats. In four countries the writers had gone into hiding. Death threats also prompted self-censorship for many writers. Most of the threats did not come directly from governments but from individuals who professed to be offended by the writer’s words. The offense, however, was almost always tied to a political or religious position, and the writer’s life became a political, not a moral, consideration.

While issues of communal violence and religious and political Islam differed from the rights of ethnic minorities in Northern Greece or from political probity in Argentina, Guatemala, Peru, Paraguay where PEN listed high numbers of death threats, the common need in all these cases was for the government to protect the writers and take action against those who issued the threats.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 12: Tolerance on the Horizon?

Voices Around the World

I began this blog four years ago with modest ambition. Once a month I would pause from writing fiction or other work and weave disparate threads of the month’s events and my thoughts together and share in this new form: the blog post. The posts have often had international themes and freedom of expression themes because work and life lead me to other areas of the world and because the freedom of the individual to write, speak and think is fundamental, especially for a writer.

By posting a monthly blog I also sought to join the 21st century in digital form, but the digital century is rushing so fast that a website with a blog post seems almost obsolete. (By next month I hope to have joined, or at least touched, the social media by also posting on an “author’s page” on Facebook.) Whatever the medium, however, the message remains, and the connection of voices around the world has become transformative.

Each month notices of writers under threat come across my desk. I find myself studying the pictures of the writers when there are pictures, writing down their names, and when available, reading some of their work to make them real in my own mind and imagination and later to share their work, which governments hope to silence. Along with other members of PEN I write appeals on their behalf with no definitive measure of how effective these are, but over time the accumulation of protests from writers and others around the world does push open consciousness and prison doors.

In the past month, writers have been imprisoned with long sentences in China, Ethiopia and the Cameroons, had an expired sentence extended in Uzbekistan, been killed in Mexico, threatened with death in India, and released in Myanmar and Vietnam.

China remains the country with the most writers in long term imprisonment, including Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo, who’s serving an 11-year sentence. In the past month, Chen Wei and Chen Xi have been sentenced to nine and ten years for “inciting subversion of state power,” in part for essays and articles they wrote online criticizing the political system in China and praising the growth of civil society. Zhu Yufu was indicted this month on subversion for publishing a poem online last spring that urged people to gather to defend their freedoms.

In Ethiopia Elias Kifle, an editor of a US-based opposition website, was sentenced to life in prison in abstentia and two journalists who covered banned opposition groups were sentenced and are now serving 14-year terms.

In the Cameroons Enoh Meyonnesse, author and founding member of the Cameroon Writers Association, has been held in solitary confinement and complete darkness for thirty days and denied access to a lawyer and has been sentenced to the harshest conditions for at least another six months.

Muhammad Bekjanov, Uzbek journalist and editor of the now defunct opposition newspaper Erk, had completed his twelve-year prison term, but this month was given an additional five years.

In Mexico reporter Raul Regulo Garza Quirino was gunned down by a gang and became the first journalist in Mexico murdered in 2012. In the past five years over 37 journalists and writers have been killed in Mexico and at least eight disappeared. Most reported on corruption and organized crime.

In India this month Salman Rushdie pulled out of the Jaipur Literary Festival after he was warned by intelligence sources that members of Mumbai’s criminal underworld had put a price on his head.

The redeeming news of the month comes from Myanmar, which still has an estimated 1000 political prisoners, including at least five writers, but the government has released poets, writers and journalists Win Maw, Zaw Thet Htwe, U Zeya and Nay Phone Latt and in late 2011 released Zarganar and lifted restrictions on Aung San Suu Kyi.

And in Vietnam blogger and university teacher Pham Minh Hoang was released, though numbers of writers remain in prison in Vietnam.

Each case has its own individual story, but all share the story of a writer writing what others feared and did not want read. Some cases are complicated by other circumstances, but many are surprisingly straight forward.

The case of Zhu Yufu began with the poem he wrote and posted at the time of the revolutions in the Middle East. The authorities took almost a year before they decided to prosecute him. Zhu’s lawyer said Zhu had nothing to do with the online calls for “the Jasmine revolution” in China; those calls began on overseas Chinese websites.

Below is Zhu Yufu’s poem “It’s Time”:

“It’s time, people of China! It’s time.

The Square belongs to everyone.

With your own two feet

It’s time to head to the Square and make your choice.

“It’s time, people of China! It’s time.

A song belongs to everyone.

From your own throat

It’s time to voice the song in your heart.

“It’s time, people of China! It’s time.

China belongs to everyone.

Of your own will

It’s time to choose what China shall be.

–by Zhu Yufu (translated by A.E. Clark)

Two Delhi Stories: Going to the Movies and Elephants Are Forever

Going to the Movies

Sitting on a thin gray-pink mat on the train platform, the children are waiting for us. We make our way over stones and past garbage, through a chain-link fence to what looks like an abandoned station. Along the tracks shanty houses and rows of laundry line the route a few feet from where the trains will come whizzing by. Some of the children, ages 5-15, live here, but most don’t have homes. They are the street children of Delhi, India, a population estimated between 150,000 to one million in Delhi alone. Some have grown up in the city and left their homes but more have stowed away on trains and arrived from the countryside or other cities looking for their future.

We are visiting Salaam Baalak [Salute the Children] Trust which works with these children to help return them to their families if that’s possible. But if the children have been abused or the parents have sold them to traffickers, they are not returned. In that case training, schooling and places to live are sought.

Our guide is a teenager who himself had lived on the street but for whom intervention made the difference. He notes that for most children, the street will prevail. He explains that 300 trains come into Delhi every day at different stations, and the children slide off of these. If they aren’t found within a few weeks, it is difficult ever to get them back for they may be trafficked for labor or prostitution or petty thievery or just become denizens of the streets.

“We go to the train stations and look for the new children,” he says. “We can recognize the new ones; they are looking for help; they don’t know anyone. Kids living on the street learn how to survive, but anyone on the street for a few weeks starts to enjoy the freedom not knowing what may yet be in store.”

Many of the children hide at the stations, waiting for the luxury trains to come through. While the train is stopped, they scurry into the cars to gather the discarded magazines and food which they later sell.

“What do you think they do with the money they get?” our guide asks.

“Buy food?” someone suggests.

“Yes.”

“Buy drugs?”

“Usually glue to sniff, yes. But the largest amount of their money goes to films.”

“Films?” we ask.

“The cinema. On Fridays when the new films come out, the children wash, clean their clothes and go to the movies!”

For a few hours a week the children soar away in their imaginations and exist somewhere else. The question hovers how to feed and nourish these minds so they can in fact someday soar away and live somewhere else.

Elephants Are Forever

In the middle of one of Delhi’s larger slums the Katha Khazana School serves the community from infants to parents and focuses on pre-school through level 12. The school is for children of the most impoverished; many are rag pickers who search through the city’s dumps with their parents for items to use or sell.

Children enter the brightly colored arched gateway of the Katha Khazana School into a sprawling open spaced building with courtyards and arched doorways, decorated with startlingly original art—brightly colored and friendly snakes, dragons, lions, tigers, fish–all swimming, prancing, hanging on the walls. At the end of one corridor a round-faced elephant with big pink ears and a trunk extended into the hall greets the visitors. The art is by the children and is added to and replaced every quarter when the theme of study changes. This year’s theme, through which the curriculum of language, social studies, civics, math, science, art, etc. is focused is Sustainable Environment, and the particular focus this quarter is: Elephants Are Forever!

My guide Sadik started six years ago at the Katha school and now at age 18 is about to graduate and hopes to go on to college. He also works with Katha, which has 50 early childhood centers and 96 primary schools, publishes children’s books and works with women on small income generating businesses in sewing, cooking, and teaching. In the past years, the women have earned hundreds of millions of rupees in their projects and have been able to lift their families out of poverty.

“Katha started with a few children in 1988,” said Geeta Dharmarajan, executive director. “We soon realized we couldn’t change the way the slums look, but we could bring people out of them. We hope to educate the children to be leaders in their communities.”

Today Katha helps children and their mothers in 72 slums and street communities across Delhi. It is just one of many organizations working in the communities in Delhi with staff and volunteers to facilitate the transition from the street by changing first the landscape of the mind.