Posts Tagged ‘Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’

Storm Cloud on a Summer’s Day

It is an almost perfect summer day—the sun is shining in a white cloud sky; the air is warm, not yet sweltering. Light filters through white umbrellas shading diners at the outside restaurant by the park. On this almost perfect New York day I am thinking about the rulers in China who have imprisoned for the last nine years one of the country’s courageous thinkers for ideas that will outlast him and his jailers.

Today it was announced Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo is in critical condition, on medical parole having been given a terminal diagnosis. As a principal author of Charter’08 which advocates for nonviolent democratic reform in China, Liu Xiaobo, writer, critic and activist has lived his life as a man of ideas.

As the sun shifts above me, skirting over skyscrapers, finding a gap between the umbrellas and spreading over my table, I consider the trajectory and the life of an idea as it dawns, unfolds, iterates, then flies off where it is embraced, where it empowers and takes on a life of its own. Ideas are connected to, but not owned or encumbered by, those who articulate them.

The fallacy—the fundamental fallacy—of the rulers in China and elsewhere lies here. No one can imprison ideas. No one can manage or own the imagination of another. Government leaders can physically restrain with the hope that the idea will die, but in the case of Liu Xiaobo, the ideas behind Charter ’08, which was signed by more than 2000 Chinese citizens from all walks of life, endure. These ideas calling for a freer society continue to grow wings, often quietly, but sometimes even more quickly as the physical confines grow harsh.

“Any man or institution that tries to rob me of my dignity will lose,” declared Nelson Mandela. It is an injunction worth noting.

American Writers Museum Launches in Chicago

by Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, published in World Literature Today, May 10, 2017

The new American Writers Museum, opening this May in Chicago, celebrates American literature in a lively, interactive space that honors America’s writers past and present.

Located on the second floor of a grand old building on Michigan Avenue’s “Cultural Corridor,” the American Writers Museum is the realization of a seven-year journey that began with a question: Why was there no national museum in the US honoring writers? Malcolm O’Hagan, a dedicated reader and retired engineer and businessman, had visited the Dublin Writers Museum in his native Ireland and began to talk with friends and professionals about developing an American museum. He brought on writers, scholars, and publishers to develop the idea and curate the selection of writers. All agreed the focus should be on writers no longer living who’ve stood the test of time, but the museum should also celebrate contemporary literature with readings, book signings, and programs.

“I see the museum as a literary jewel box where a visitor can enjoy old friends—the books, words, characters of writers they know and also get to meet new ones,” O’Hagan says. Chicago was selected because of its central location, the support of the city, and its rich literary heritage, which includes writers like Carl Sandburg, Saul Bellow, and Gwendolyn Brooks.

One of the governing principles was not to create a museum for static artifacts—though there will be some artifacts—but a place where readers, writers, and visitors can learn. “Books in glass cases don’t make for much engagement,” O’Hagan notes.

A large US map greets visitors with a Nation of Writers introductory film playing on it. On one side of the map is a room dedicated to children’s literature with places to read, word games, and story times with authors. Down the corridor runs the Gallery of 100 American Voices—from early Native American storytelling to Thomas Jefferson, Sojourner Truth, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, John Steinbeck, Eudora Welty, Ralph Ellison, and many others, a rich collection spanning American history. On the facing wall a Surprise Bookshelf features illuminated boxes showcasing samples of great American literature. A Word Waterfall stands at the end of the corridor where quotes by writers from Emerson to George Carlin stream down the wall.

As you turn into the Readers Hall, which is also an event space, kiosks let readers explore their favorite books and compare them. At the end of Readers Hall, a changing display space launches with the return of Jack Kerouac’s scroll of On the Road after a decade out of the country. Another space features W. S. Merwin.

In the nearby Writers Room a visitor can glimpse the creative process in an exhibit entitled Mind of a Writer. Two eight-foot touchscreen tables display book titles the visitor can open to view edits on manuscripts such as The Fall of the House of Usher and A Streetcar Named Desire. The display Anatomy of a Masterpiece includes quotes from writers about the creative process.

A large, windowed alcove is dedicated to Chicago writers. Another feature, Hometown Authors, lets a visitor enter a zip code and find writers past and present in his or her area, including local museum affiliates. The over sixty affiliates are houses and smaller museums around the country dedicated to single authors.

The museum plans to partner with literary and educational institutions nationwide. AWM president Carey Cranston says, “Once our doors open, we will learn from people coming through, and ideas will flow day by day. The feedback will help us going forward.”

“Whatever we do, we must represent all of America’s diversity,” adds Program Director Allison Sansone. “What makes American literature different is the diversity of voices and our willingness for self-examination.”

Novelist and journalist Joanne Leedom-Ackerman is vice president of PEN International and sits on the boards of Poets & Writers, PEN Faulkner Foundation, International Center for Journalists, Words Without Borders, and the American Writers Museum.

(Click here to read the article at World Literature Today.)

For Syrian refugees in Lebanon, a drive to build community amid pressing challenges

Communities spring up in the buildings and spaces where families manage to find a spot. Many refugees say their hope is in giving their children a better future.

By Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, published in The Christian Science Monitor, February 27, 2017

Beirut, Lebanon—I remember Syrian children living by a garbage dump near a cement factory where their parents did menial labor when I visited Lebanon three years ago. I remember those living in an unfinished shopping mall with open storefronts, several families camped in a space supposed to be a shop, except that the developer had run out of money and never finished the building. Now he could collect rent from the refugees.

Syrian refugees were pouring into Lebanon in 2014, fleeing the civil war. The United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) and nongovernmental organizations were scrambling to register and provide services for these families, most of whom hoped to return to Syria when the war was over. Because Lebanon has a history dating back to the Palestinian diaspora of not providing camps for refugees, the displaced were finding shelter wherever they could. The effort to get children into schools was beginning. One aid worker described the situation as trying to give cups of water to people from a blasting firehose.

I recently returned to Lebanon to visit the Syrian refugees. I was in Beirut when President Trump’s edict on immigration and his ban on all Syrian refugees to the United States was announced. The ban included Syrian families in Lebanon who had been going through the long vetting process to resettle in the US. Lebanon has the largest percentage of refugees given its population – more than 1 million registered in a country of 4.5 million citizens.

The situation in Lebanon remains deeply challenging, with pressing needs. But it has stabilized. The flow of people across the border is now a trickle, not a flood, and the systems to assist are more firmly in place. When the refugee population hit the 1 million mark, Lebanon changed its open border policy. But the Syrian refugees remain more than 20 percent of Lebanon’s population, the equivalent of 64 million in the US. Last year the United States accepted 10,000 Syrian refugees out of an estimated 4.8 million worldwide.

Three years ago, Lebanon had only 150 schools that had split shifts, teaching the Syrian children in the afternoon. Today half of the Syrian children are in government schools – more than 200,000 children, according to UNHCR officials. UNHCR pays the Lebanese Ministry of Education $600 per child to assist in the cost. Some children may be enrolled in private schools, according to officials, though the remaining are still not in school, including those who work to bring in income for their families, and, in the case of girls, those who are married off as young as 14 or 15.

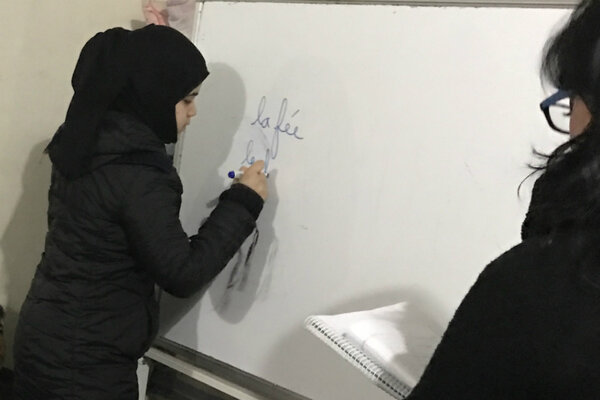

Writing plays and tutoring in French

A difficulty for Syrian school children is language; Lebanese schools teach in French or English in addition to Arabic. One 12-year-old girl dressed in black headscarf practiced French with a local volunteer in a homework support group. The girl has been living in Lebanon for 3-1/2 years. She was in fifth grade when she left Syria, but she’s lost years of schooling, and because she doesn’t know French, she is now placed in third grade. She is friends with some of the Syrian children in her school, but with few Lebanese children. “They don’t like to talk about the same things,” she said. “What do you like to talk about?” I asked. “I want to talk about the war.”

Hasan, 13 years old, remembers going to school in Aleppo, and has been in Lebanon three years. He’s glad to be in school again, but he too has lost several years of education and is in an early elementary class.

For elementary school children, the transition is not as difficult since they can learn French or English, but older Syrian students are struggling. Homework support groups have grown up and are sustained by UNHCR and Save the Children. In Batroun, a town in the North, a Lebanese teacher volunteers twice a week to tutor French. Other outreach volunteers assist in other subjects. One young man, Joseph, helps the children by writing plays and doing small theater productions with them. A Syrian, he receives his work expenses and training. But, he said, “I volunteered to help my people. At the beginning I wanted to volunteer in any sector, but I believe education is very important. I started a small theatrical team, selected the children, wrote small plays with a message, and we perform in a small garden Saturday or Sunday for the community.”

Building communities has been essential for the children and their families, especially since return to Syria remains problematic. These communities grow up in the buildings and spaces where the families live. Approximately 60 percent of the refugees rent apartments, often crowding several families into one or two rooms, carpets and pillows on the floor, a single television in the corner, a light bulb on the ceiling. UNHCR has helped in reconstruction of buildings with an agreement from the landlords that they will rent at reduced rates to the Syrian refugees for a period. Other refugees have built temporary shelters on the roadside. Simple wood frames with tarps and plastic sheeting dot the landscape in the north, perched on farmers’ land where refugee men and women work in fields of orange groves, olives, cucumbers, and potatoes.

Guests, with work restrictions

The Lebanese government has said it is treating the Syrians as “guests” and does not deport them, but the government restricts where the Syrians can work. To get a residency permit, they have to agree not to work except in agriculture, construction, or environment (cleaning) – all low-wage areas. The government also requires that refugees re-register every six months, paying $200 per person over 15 years of age. The cost is prohibitive for many families, so the men in particular live in fear that they will be arrested for not having proper registration, and this limits their mobility in finding employment, according to aid workers.

While refugee services from the UN, nongovernmental organizations, and the Lebanese government have increased in recent years, so have the poverty rates, as families have spent the money they brought with them. According to UNHCR statistics, 70.5 percent of the refugee population live in “extreme poverty,” meaning they live on less than $3.80 per day. UNHCR provides cash assistance, but to only 22 percent of these families. With the cash cards they can buy food, supplies, and pay rent. As winter arrived, additional small payments were provided to help buy blankets, warm clothes, and fuel.

Many of the refugees say their hope is in giving their children a better future, but in Lebanon that future has a ceiling. “At least we have a real school now and one close. It is much easier for our children,” says one mother. But with livelihood possibilities tightly controlled and the possibility of affordable residency curtailed, many parents don’t see an expanding future in Lebanon. UNHCR tries to assist those who want to resettle elsewhere, but even before the recent US ban on Syrian resettlement, the possible openings were diminishing.

“UNHCR’s top recommendation in Lebanon is a waiver of the residency fee so that the refugees are all legally registered and can work. This will help provide employment for them and a work force in needed areas of Lebanon, and income that can then be spent in the local economy,” says Karolina Lindholm Billing, UNHCR deputy representative.

“When you used to look out over Beirut at night, you would see black on top of the buildings,” she notes. “Now you see the lights of refugee settlements there – tents and cooking fires. The refugees have found whatever space is available and gotten permission from the landlords and pay rent.”

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman is a novelist and journalist who has traveled in the Middle East and visited the refugee settlements in all the countries bordering Syria and has recently returned from Lebanon. Ms. Leedom-Ackerman is a former reporter for the Monitor.

(Click here to read the article at The Christian Science Monitor.)

In Turkey, a show of solidarity with writers behind bars

Commentary: For the first time in two decades, Turkey is again the largest jailor of writers and publishers in the world. A PEN International delegation tried to visit a prison where most are incarcerated.

By Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, published in The Christian Science Monitor, February 3, 2017

Snow was falling outside Silivri prison as we drove up the road bordered by high wire fences. A senior delegation of PEN International from Europe, North America, and the Middle East had come to Turkey in solidarity with the more than 150 Turkish writers and publishers now in prison. The majority of these were incarcerated behind the walls of Silivri.

For the first time in two decades, Turkey is again the largest jailor of writers and publishers in the world. Under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who came to power in 2002, civil institutions have been increasingly circumscribed. In the past six months more than 170 news outlets have been closed by the government. A third of Turkey’s judiciary – judges and prosecutors – have lost their jobs and/or been put in prison. University presidents have been fired; thousands of academics have been forced to resign, and more than 140,000 civil servants and military personnel have been purged; a third of these are now in detention. Ever since a coup attempt last July, Turkey has existed in a declared “state of emergency.” Those who oppose the government have been labeled and charged as “terrorists” or “supporters of terrorist organizations.” The crackdown that was already under way before the coup attempt has escalated.

At Silivri, our delegation was restricted to a remote parking lot. The prison officials had been notified the delegation would be arriving, but the gendarmes who encountered us appeared unprepared. Eventually they returned us to our minivans and encircled these and blocked us with police vehicles as they collected our passports. A young gendarme with an assault rifle boarded our bus, impeding our exit for almost an hour, though he appeared unsure of what he was supposed to do with us except keep us from taking pictures. Finally the delegation, which included three current and former International PEN presidents, including the current chair of the Nobel Prize for Literature, were escorted away from the prison. There was no interchange with prison officials or meetings with the writers behind bars. The cars were stopped again outside the grounds by the police, and our passports were once more collected. After approximately two hours, our two white minivans turned back to Istanbul.

Earlier, in the Turkish capital of Ankara, a smaller delegation of PEN met with the minister of Culture and other government officials to protest and express deep concern over the restriction of free expression and the imprisonment of writers and publishers in Turkey. PEN questioned the legitimacy of the constitutional referendum President Erdoğan is putting on the ballot this spring. The referendum will expand the powers of the presidency, giving Erdoğan the ability to suspend parliament as well as rights and due process, “extorting individual rights and freedom” by statutory decree. It could allow him to stay in office until 2029. While PEN, which promotes literature and defends freedom of expression worldwide, does not take political positions, it challenged the legitimacy of a referendum held during a state of emergency, when opposition voices are silenced.

After our delegation returned from the prison to Istanbul, we met with recently released writer Asil Erdoğan (no relation to the president), linguist Necmiye Alpay, and others, including the spouses of writers still in prison or killed. “It is not our husbands in prison, but journalism,” said the wife of one. “Journalism is a prerequisite for a country to have a free press. If we don’t have a free press, we can’t be considered anything. Don’t use the word “journalist” and “terrorist” together. It is very sad to see.”

Several of the writers noted that often no indictment is made when individuals are detained. They are held without charge because the prosecutors can’t find anything to charge them with. See #Journalismisnotacrime.

A new effort

One newspaper, Özgür Gündem, which had a large Kurdish readership, was shut down in August after 25 years. But a new newspaper, Demokrasi, has grown up out of its staff and readership.

At the top of a steep four-floor walkup, writers, photographers, and editors work to put out the daily paper with a readership of 30,000. The design and layout team work elsewhere as do some of the writers and other organs of the paper, in the belief that the more decentralized the operation, the better chance it has to survive.

“The government wants to eliminate the Kurdish movement – the language, the news we report. They want a single state, single religion, single language,” said one of the editors. “Kurds are not only the target; our newspapers are the target. We are OK with a single flag, but we don’t want religion and language imposed.”

The Turkish government has fought with Kurdish separatists for decades. A cease-fire from 2013-15 held out prospects for a more lasting peace and for the allowance of Kurdish language and culture to be recognized as part of Turkish identity. The rapprochement broke down, however, after the predominantly Kurdish HDP party won enough votes in June 2015 to secure seats in parliament and deny Erdoğan and his AKP party its parliamentary majority and the supermajority he was seeking for his constitutional changes. Hostilities with the Kurds were renewed shortly afterward. A new election was held in November 2015, and the AKP party won its majority.

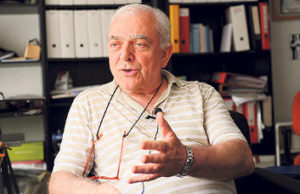

The gray-haired editor of Demokrasi spoke calmly behind an empty desk in a sparse room with pale yellow walls. He acknowledged that the state police could come at any moment to take him away, but there would be others to take his place. “We received support from 100 journalists who volunteered to be editor-in-chief at Özgür Gündem. Thirty-seven of those are now on trial. But it is not a problem for us to repeat.”

As we left the Demokrasi office, the editor with his photographer stood at the top of the stairs in the shadow of a half-opened door, the light behind them. “Thank you for solidarity!” he said.

When we emerged, the sun was setting. The winding backstreet was filled with people as the lights of shops and apartments readying for dinner flickered on, and the snow continued to fall.

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman visited Turkey as part of a delegation from PEN International, where she is a vice president. Ms. Leedom-Ackerman is also a former reporter for the Monitor.

(Click here to read the article at The Christian Science Monitor.)

Power on Loan

The first march I covered as a journalist was a massive anti-war moratorium in Boston in the spring of 1970, part of nationwide protests; Boston was one of the hub cities. The demonstrators walked peacefully from the Boston Commons through the city to Harvard Square in Cambridge. But as the day and evening wore on, the demonstration descended into violence in Cambridge with Molotov cocktails thrown through store windows and police dogs and tear gas aimed at the crowds. I took refuge eventually in the basement of a church where I wrote my story.

America was on the march back then against the Vietnam war and in earlier protests in favor of civil rights. Though there was violence, most of the demonstrations remained nonviolent.

In the intervening years there have been many marches and protests in the U.S., but few like the ones held around the country this past weekend. These nonviolent demonstrations in cities in every state and in 55 cities worldwide focused on a more loosely articulated goal, not on specific legislation or a specific action but on showing solidarity, particularly with issues important to many women like freedom of choice over their bodies and also on issues such as the rights of immigrants, of minority communities, and of the LGBT community.

There was also apprehension about exactly what the new President’s “America First” policy will mean. Demonstrations around the world showed that America’s positions are not just the concern of U.S. citizens but have impact globally.

I’ve covered and seen many demonstrations around the globe since my first march. On Saturday, I was on the edge of the gathering in Washington, witnessing, hosting and delivering one marcher who came in from Colorado to participate. As she joined the crush in the Mall, I wrote and prepared for a PEN mission to Turkey where the political situation is deteriorating daily for citizens, especially those in the media.

In the Turkish Parliament this past week fights broke out as President Recep Erdoğan proposed and got ratified a Constitutional amendment to give even more power to the president, including an article that gives the President the right of “extorting individual rights and freedom” with statutory decree. The Constitutional amendment must be endorsed in a national referendum so demonstrations in Turkey may soon begin but with potentially direr consequences than in the U.S. In Turkey almost 150 writers and journalists are already in prison, not for crimes, but because they have dissented.

A few writers like Asli Erdoğan and linguist Necmiye Alpay have been released at their trial where Asli said, “Law is obliged to protect the individual and the community, not only the state.” The day they were released, however, journalist and writer Professor Istar Gözaydin, one of the founders of Turkey’s first democratic private radio, was taken into custody.

Last week musician Şanar Yurdatapan was sentenced to one year and three months in prison for participating in the “Editor-in-Chief on Duty” solidarity campaign at Özgür Gündem, the newspaper now closed. His sentence was ultimately suspended and another charge relating to the case resulted in a fine. The prosecutor had originally asked for a ten-and-a-half-year sentence. Cumhuriyet’s book editor Turhan Günay, who publishes a book index, is now in prison. He has said, “I have not written anything except for books until today. If I’m released, I will start to write political articles.”

The numbers of writers, journalists, editors and academics in prison has returned Turkey to the top of PEN’s list of jailors as it was two decades ago.

I’m wary about drawing parallels with the increasingly chilly atmosphere for the media in the U.S. I take heart that U.S. protests can occur and that the state protected the protestors, and as long as the demonstrations stay nonviolent, no one is arrested. The press can and does report what it sees even if a tongue-lashing by the Presidential press secretary and the President follow. However, six covering the turbulent demonstrations around Donald Trump’s inauguration on Friday have reportedly been charged with felonies and face up to ten years in prison and a $25,000 fine if convicted. Also some access for the press may be closing down. The dynamics of fear and antagonism and the argument of “alternative facts” create a dangerous atmosphere.

Of note, though not in the front page headlines, in Africa’s smallest continental country, The Gambia, former President Yahya Jammeh finally stepped down from power this week after 23 years, having lost the election last month but refusing to leave office. The peaceful transfer of power in the U.S. the day before probably had little to do with his decision. The arrival of troops from a coalition of West African nations supported by the United Nations and the pressure by African leaders were no doubt the persuading factor, but the coincidence is worth noting.

The turnover of power is fundamental to democracies and is not always easy, especially when the pendulum swings to the opposing side and in the U.S. to someone who has not won the popular vote. Yet after a tumultuous and harsh election, the reins of power did transfer; authority was ceded. The old guard left the stage with dignity, and the new guard must now find the dignity to occupy it effectively.

The demonstrations of four decades ago in the U.S. led to the end of a war, the implementation of civil rights legislation, advancement for race, gender and cultures, and while we still have distance to go, it has led to large strides for women in my generation.

I continue to hope the arc of history is upwards and outwards, not inwards on itself, puncturing the very progress that has been made. Whoever is in power must remember that power is only on loan, especially in a democracy.

Hope for Songs Not Prison in 2017

The last time I saw Şanar Yurdatapan we had coffee in the press building in Istanbul after Human Rights Watch released its 2016 World Report “Politics of Fear and the Crushing of Civil Society”. I’ve known Şanar for almost 20 years, ever since I headed PEN International’s delegation for his first Initiative for Free Expression in Istanbul in 1997.

A noted and popular musician and song writer, Şanar has dedicated the last decades to defending and trying to open up space in Turkey for free expression. He’s done so by monitoring, reporting and organizing on behalf of writers and artists under threat. At our coffee a year ago he told me he was retiring, or at least going back to song writing and handing over the mantle of leadership to the younger generation.

However, in the past year freedom of expression has been under siege in Turkey with 150-170 writers and journalists now in prison and hundreds of news organizations closed down. This past week Şanar was called before prosecutors for his advocacy on behalf of the closed newspaper Özgür Gündem, (Turkish for “Free Agenda”), the chief newspaper read by Kurds.

“It is both the duty and the right of a journalist to report; his is freedom of information at the same time and right to freedom and right of all of us,” Şanar is reported to have told the court.

At the end of the hearing the prosecutor demanded that Şanar be imprisoned for over ten years for “propaganda for the organization” under the Anti-Terror Law. The hearing is January 13, 2017. Şanar is now 75.

Since the failed coup in July the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has increased the detainment and arrest of writers, journalists and academics for their peaceful opposition to his policies. These have included noted novelist Asli Erdoğan and leading linguist Necmiye Alpay, who spent her 70th birthday in detention. Brothers Ahmet Altan, a novelist, and Mehmet Altan, an academic, are held in maximum security Silivri prison facing terror charges, unable to receive books, letters or any communication from outside or to visit the prison library.

As the year 2016 ends with an increase of terror attacks around the world, with a new administration about to take power in the U.S., with existing administrations struggling to hold onto power in Europe, with a collapsing Syria and a continual tide of refugees around the world, with an odd dance between super powers and aspiring super powers, the single citizen voice can get overlooked. But history has shown that when the individual voice, especially those of writers who dissent, gets stifled, the arc of history is bending towards conflict and away from peace which leaders and citizens say they want.

In the new year PEN International hopes to go to Turkey to add support firsthand for Turkish writers and for the important role they play right now in keeping that arc from bending too far backwards. We will watch and argue for the fate of Şanar and others and hope that he will be writing songs in the years ahead, and not from prison.

Thanksgiving and Healing

The American holiday Thanksgiving is my favorite, a time when family and friends gather and take a moment to give gratitude for the good in their lives and the lives of their communities. This year of 2016 has been a rough one.

In Washington, DC, where I live, the political discourse on all sides has been as uninspiring and acrimonious as any in my lifetime. No matter one’s political affiliation, consensus is that the recent presidential campaign has left us exhausted with the national conversation in need of elevation and inspiration.

Many opposing the election results have taken to the streets peacefully to articulate their concerns and their fears. The crowds include the young—high school students who are not yet old enough to vote—and the retired as well as the population in between. Whatever one’s vote, I take heart that for the most part these protests are not violent and can be heard. I take heart that the leadership in the nation has accepted the transition and will try to make it successful and that in practice we do not jail or shoot opposing voices or those writing about the opposition. This seems a minimum standard for a democracy, and though it has seen exceptions, in this season of thanks, I am grateful and hopeful that will abide.

Historically Thanksgiving was a day to give thanks for the harvest of the preceding year. In the U.S. the first Thanksgiving is documented in 1621 at Plymouth (now in Massachusetts). The harvest was good, and the new settlers and the local Wampanoag tribe shared the feast, though more uneasily watching each other than we were told as school children. During the American Civil War Abraham Lincoln advocated the story of Pilgrims and Indians eating together to try to encourage people in a divided nation to come together.

Healing occurs one action at a time, one forgiveness, one helping hand, one quiet good deed. Citizens can take the lead. I am hopeful that we individually—the people—will build bridges and not walls. Happy Thanksgiving!

Building Literary Bridges: Past and Present

Gathered in the ancient city of Ourense, Spain in the heart of Galicia, writers from around the world celebrated history, debated the present and committed to the future of literature and freedom of expression at PEN International’s 82nd Congress organized around the theme “Building Literary Bridges.”

Two hundred poets, novelists, dramatists and nonfiction writers from approximately 75 centers of PEN agreed to embark on a three-year global campaign to increase opportunities for displaced writers worldwide. Responding to the unprecedented flow of refugees, migrants, and displaced, all of which include writers and those whose stories need to be told, the 95-year old literary organization will undertake an initiative to put storytelling and literature at the center of an effort to heal and expand opportunities. Through its 145 centers, PEN will develop programs that will include residencies, workshops, mentoring, education and publications. The full scope of the campaign will be announced December 10, Human Rights Day.

Founded in 1921 out of the chaos and refugee flows after World War I, PEN anticipated and protested the suppression of freedom of expression in Nazi Germany prior to World War II and defended writers throughout Europe during the war, offering haven and setting up PEN centers in exile.

“PEN responds to the crises of our times,” said PEN International President Jennifer Clement. “We are writers. We believe in imagination.”

The 82nd Congress began with heartening and dispiriting news. Iranian-Canadian writer Homa Hoodfar was released from Iran’s Evin prison at the same time news arrived that Jordanian columnist Nahed Hattar had been gunned down outside court by a fundamentalist who claimed Nahed deserved to die for his ideas.

This pattern of good and terrible news also emerged in the past year with early releases of imprisoned writers in Tibet, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Vietnam, Qatar and Colombia at the same time the situation deteriorated with more arrests and killings in Bangladesh, China, Turkey, Ukraine and other countries.

The tradition of an Empty Chair at the PEN Congress sessions highlighted the cases of imprisoned Egyptian novelist Ahmed Naji, Kurdish journalist Asli Erdogan, Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour, and Gui Minhai, a bookseller in Hong Kong, who was kidnapped by the Chinese government while he was in Thailand.

Gui’s daughter, a Swedish citizen as is he, sent a letter to the Congress: “In the end, this is not about my father as an individual…. This is about China actively extending its control far beyond its own borders. This is about China kidnapping and illegally detaining more and more people because of their political beliefs. It’s about European citizens no longer being able to know that their human rights will be protected.”

Discussing “Literature as a Tool for Empowerment,” delegates shared ongoing projects, including working with young writers in schools and in prisons. Lebanon PEN Center’s delegate noted, “I discovered the tremendous effect from creative writing to express trauma and help people tell their stories. We have 1.3 million Syrians in Lebanon. We have a big responsibility. We see the empowerment of civil society through literature.”

In Mali and Sierra Leone, the PEN centers work with students and young people in post-conflict situations. The Mali delegate spoke about workshops with Tuareg warriors who had fought on the battlefield in the Sahara. When they returned home, they had lost their dignity and positions and were migrants so they went to join the ranks of Gadhafi. After Gadhafi was toppled, there was a big problem, he said, and conflict. The Mali PEN Center helped organize writing workshops which led to publishing books. Hundreds attended these workshops and were able to tell their stories and see them published.

PEN’s earliest work to protect writers began when poet Federico Garcia Lorca was arrested at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. PEN President H.G. Wells sent a telegram protesting, but it arrived too late and Lorca was executed. At the 82nd PEN Congress, Lorca’s niece Laura opened the Assembly with Lorca’s poem Sonnet:

I know that my profile will be serene

In the north of an unreflecting sky.

Mercury of vigil, chaste mirror

to break the pulse of my style.

For if ivy and the cool of linen

are the norm of the body I leave behind,

my profile in the sand will be the old

unblushing silence of a crocodile.

And though my tongue of frozen doves

will never taste of flame,

only of empty broom,

I’ll be a free sign of oppressed norms

on the neck of the stiff branch

and in an ache of dahlias without end.

–Federico Garcia Lorca

Sounds of Summer

(This is not a poem)

August on the Eastern shore

Quiet on the river

Birds chirruping in the trees

Crickets—or are they cicadas—clicking in the afternoon, clicking that will build to a crescendo in the evening

CaCaCa of peacocks next door

Water trickling, flowing slowly out to the bay

A power boat whishing by, heading to the open water

A leaf blower, a lawn mower in the distance, jarring the quiet

Leaves rustling in the breeze

Breeze skimming the trees, rustling, rushing louder now, emboldened

More birds chirping, the beginning of a larger conversation

At the very top of a tree at the river’s edge a black bird keeps watch, looking first out to sea then to land, then trips lightly along the branches, lets out a caw and flies away.

I sit here, listening to all these sounds of late summer.

I sit here, listening to all these sounds of late summer.

Soon the children will come home from camp, run outside, filled with their day—karate lessons, swimming, new friends—but for now in the quiet, I am “happy in my circle of oblivion,” to borrow a phrase from Garcia Márquez, whom I’m reading on this rare, undisturbed afternoon.

The news—the sturm and drang of presidential politics, the daily offenses—are outside this space on the river. For a brief moment the troubles of the world seem held at bay. Even the trials and triumphs of the Olympics must await the evening news.

I watch three billowing white clouds drift by ever so slowly in the blue sky.

As the breeze picks up, the trees rustle, continuing a conversation, stirring first one tree then another, passing along the wind’s gossip down the river bank.

If this light wind holds, it will be good kite-flying weather in the evening. We can have another picnic by the river with grandfather sitting in the Adirondack chair and everyone else on the grass—hot dogs, hamburgers, corn, applesauce, kite in the air, children running, laughing.

The parade of clouds drifts by overhead now like characters in the children’s play they plan for the grownups. “One, two, three…look at me!” The black dog passes all dressed up to play a part in the drama as he looks for scraps from dinner. The shapes of the clouds pass and just blue sky shines overhead. We will end the evening with S’mores at the fire pit as the moon rises over the river.

There are only three more weeks of summer—more books to read, stories to write, laps to swim, thoughts to think before the demands of schedules and meetings and deadlines crowd in.

For this moment I am grateful for the silence, the breeze, the birds, the river, the shining sky, the billowing clouds and the promise of this afternoon that I will carry with me.

Call for Help inside Iran’s Evin Prison

Shared below is a letter that managed to get out of Iran’s infamous Evin Prison from journalist and human rights activist Narges Mohammadi. She is detained on charges of “gathering and colluding to commit crimes against national security” and “spreading propaganda against the system.” According to reports she has also been charged with “insulting officers while being transferred to a hospital” because of her health. Narges Mohammadi is former vice president and spokesperson of the Defenders of Human Rights (DHRC) which represents prisoners of conscience. She is also involved in a campaign against the death penalty in Iran.

On May 17 the verdict in her case was handed down. Narges Mohammadi was sentenced to five years in prison for “meeting and conspiring against the Islamic Republic,” one year for “spreading propaganda against the system” and ten years for her work advocating against the death penalty. Under Iranian penal code, a person with several jail terms must serve the most severe so she must serve ten years, although sentenced to 16 years total.

Dear members of International PEN,

I’ m writing this letter to you from the Evin Prison. I am in a section with 25 other female political prisoners, with different intellectual and political point of view. Until now 23 of us, have been sentenced to a total of 177 years in prison (2 others have not been sentenced yet). We are all charged due to our political and religious tendency and none of us are terrorists.

The reason to write these lines is, to tell you that the pain and suffering in the Evin Prison is beyond tolerance. Opposite other prisons in Iran, there is no access to telephone in Evin Prison. Except for a weekly visit, we have no contact to the outside. All visits takes place behind double glass and only connected through a phone. We are allowed to have a visit from our family members only once a month.

But it is the solitary confinement, which is beyond any kind of acceptable imprisonment. We – 25 women – have detained in total more than 12 years in solitary confinement. Political prisoners who are considered dangerous terrorists are held in solitary confinement indefinitely. Retention in solitary confinement can vary from a day up to several years.

However, according to regulations of the Islamic Republic of Iran, holding prisoners in solitary confinement is illegal. Unfortunately until now, the solitary confinement, as a psychological torture, has had many victims in Iran.

During 14 years long activity of the Center for Human Rights Defenders, the Center have published and held many protests against the use of this kind of punishment. But unfortunately the solitary confinement is still used against many of Iran’s political prisoners. The solitary confinement is used to get forced and false confessions out of the defendants. These false and faked confessions are used against the defendants during the trials. Many of the detainees in the solitary confinement are suffering from mental and physical health problems and the injuries will remain with them for the rest of their life. As a matter of a fact, the solitary confinement is nothing but a closed and dark room. A dimly confined space, deprived of all sounds and all light that can give the inmates a sense of humanity. Personally, I have been in solitary confinement three times since 2001. Once during my interrogation in 2010, I suffered a panic neurotic attacks, which I had never experienced before.

As a defender of human Right, who has experienced and have had dialogues with many people detained in solitary confinement, I emphasize that this kind of punishment is inhuman and can be considered psychological torture.

As a humble member of this prestigious organization, I urge all of you, as writers and defenders of the principles of free thought and freedom of speech and expression, to combat the use of solitary confinement as torture, with your pen, speech and all other means. Maybe one day we will be able to close the doors behind us to solitary confinement and no one will be sentenced to prison for criticizing and demanding reforms. I hope that day will come soon.

Greetings and Regards

Narges Mohammadi

Prison Evin, May 2016

For more information on Narges Mohammadi and suggested action, you can link to PEN International.