Posts Tagged ‘PEN’

What Are You Not Reading This Summer?

I was recently sent a questionnaire as part of a profile asking me what I was reading:

I find myself reading several books at the same time. I just finished Phil Klay’s Redeployment today, am reading Jennifer Clement’s Prayers for the Stolen, am re-reading Graham Greene’s The Comedians, re-reading Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this and can’t leave this question without noting Elliot Ackerman’s Green On Blue. Because I read both e-books and paper books, I move around among narratives easily.

The answer was a snapshot in reading time, indicative of the pleasure of dancing among narratives. I find myself enjoying on several platforms the movement between hard-edged, nuanced stories of war and its aftereffects in Klay’s Redeployment and Ackerman’s Green on Blue, the harsh and surprising world of Clement’s indigenous Mexican women in Prayers for the Stolen and the gentle, but no less desperate stories of Southern women trying to find their lives in Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this, a collection recently re-published by a new small press—Bacon Press—in paperback. Graham Greene is a master who I am always re-reading, appreciating how he integrates the international world of politics and deceit with compelling narratives set around the world.

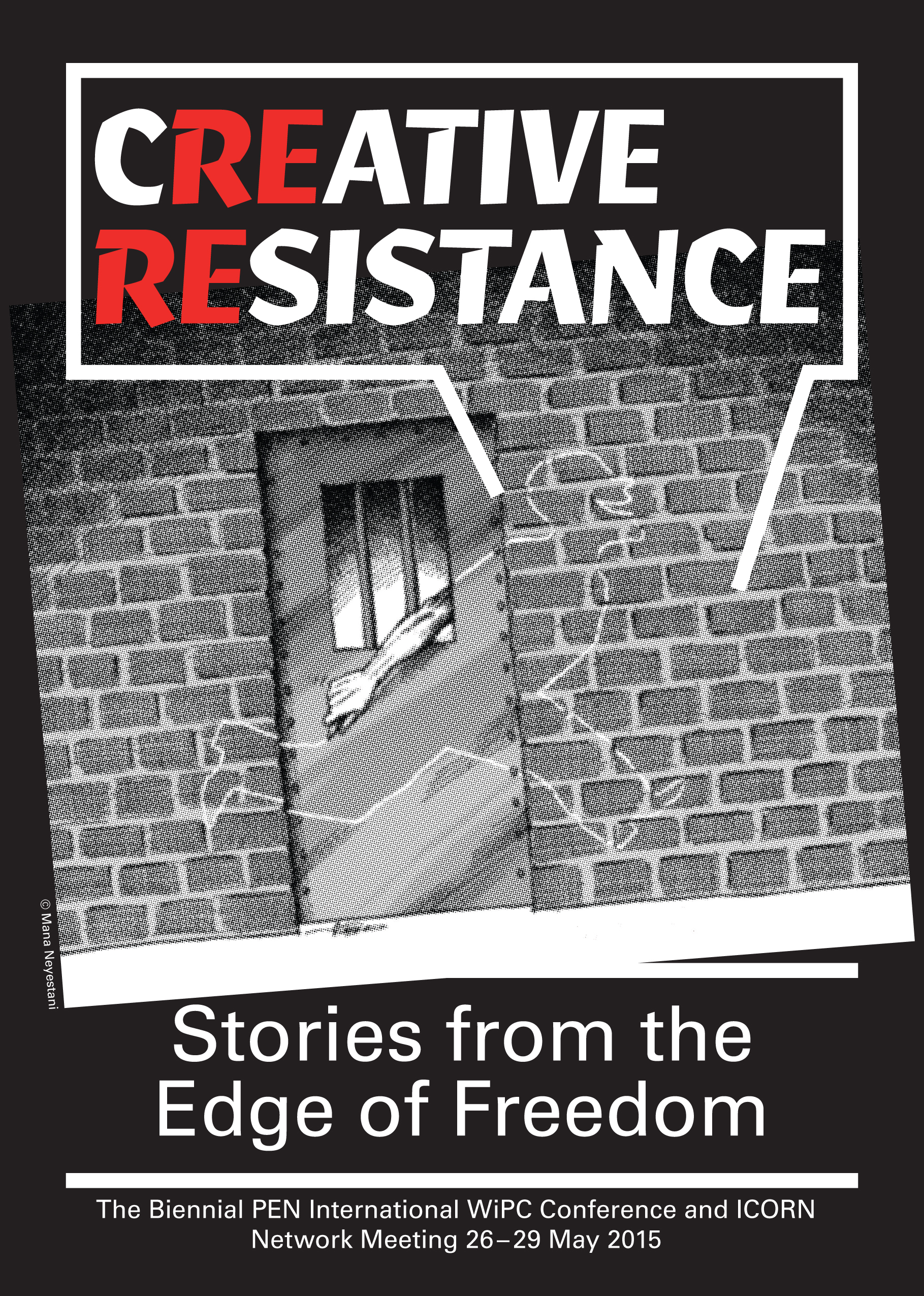

Recently I returned from PEN International’s biennial Writers in Prison conference and the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) meeting, a gathering this year in Amsterdam focused on Creative Resistance, a gathering of over 250 individuals from 60 countries around the world who work on behalf of writers threatened, imprisoned and killed for their writing. I remain conscious of these voices too. They occupy a kind of negative space—those we are NOT reading, not able to read because they are not able to write.

The list unfortunately is long, and many individuals stand out for me, but I will highlight two here. Though I couldn’t read either because of language differences, I read with attention their cases and link here to actions that can be taken on their behalf:

—Raif Badawi, a blogger and editor in Saudi Arabia, had his sentence confirmed this past week by the Supreme Court that he must serve 10 years in prison and receive 1,000 lashes for “founding a liberal website,” “adopting liberal thought” and for “insulting Islam.” Raif had planned a conference to mark “a day of liberalism,” and he launched an online forum, Liberal Saudi Network to encourage political and social debate. His lawyer has now also been arrested.

His wife, who fled with their three children, says she received threats from the Saudi embassy when she was in Lebanon that they would kidnap her children and forcibly return them to Saudi Arabia; the court verdict would force her to separate from her husband.

Though now living in Canada, she says, “I believe that there is a will for freedom in the country that will not be deterred.” Of the solidarity movements that support her husband, she adds in an interview with PEN International, “I used to believe it was a fantasy for a person to stand in support of another person regardless of geographical, racial, religious, linguistic and other differences, but what you have done for Raif’s case has taught me that I knew nothing about humanity.”

Link for more information and action.

—Gao Yu–Chinese journalist, former chief editor of Economics Weekly and contributor to the German newspaper Deutsch Wele and a poet–was arrested on charges of illegally obtaining state secrets and sharing them with foreign media and sentenced this spring to seven years in prison. When she was first disappeared, she was writing a column entitled ‘Party Nature vs. Human Nature,’ which is said to have considered the new leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and its internal conflicts. Gao Yu, who is 71, has been an intrepid journalist her whole career and an honorary director of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. She has often been at PEN conferences in Hong Kong and contributed to an essay in PEN’s 2013 report “Creativity and Constraint in Today’s China.”

She has served time in prison before, the first time for reporting on student protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and five years for reporting on political and economic issues in Hong-Kong based publications. She’s known for her critical political analysis of the inner circles of the Chinese Communist Party. Her arrest and sentencing has signaled to many the retreat from hope of wider press freedoms under the new leadership.

For those of us lucky to have met Gao over the years, we’ve seen she has a sharp mind, a smiling face and an unmistakable light in her eyes as though she is slightly amused and looking at a much longer narrative for China. At the recent PEN conference, each meeting had an empty chair on the stage, and a picture of Gao Yu as the honored writer not there.

Link to more information and action.

Voices Around the World

I began this blog four years ago with modest ambition. Once a month I would pause from writing fiction or other work and weave disparate threads of the month’s events and my thoughts together and share in this new form: the blog post. The posts have often had international themes and freedom of expression themes because work and life lead me to other areas of the world and because the freedom of the individual to write, speak and think is fundamental, especially for a writer.

By posting a monthly blog I also sought to join the 21st century in digital form, but the digital century is rushing so fast that a website with a blog post seems almost obsolete. (By next month I hope to have joined, or at least touched, the social media by also posting on an “author’s page” on Facebook.) Whatever the medium, however, the message remains, and the connection of voices around the world has become transformative.

Each month notices of writers under threat come across my desk. I find myself studying the pictures of the writers when there are pictures, writing down their names, and when available, reading some of their work to make them real in my own mind and imagination and later to share their work, which governments hope to silence. Along with other members of PEN I write appeals on their behalf with no definitive measure of how effective these are, but over time the accumulation of protests from writers and others around the world does push open consciousness and prison doors.

In the past month, writers have been imprisoned with long sentences in China, Ethiopia and the Cameroons, had an expired sentence extended in Uzbekistan, been killed in Mexico, threatened with death in India, and released in Myanmar and Vietnam.

China remains the country with the most writers in long term imprisonment, including Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo, who’s serving an 11-year sentence. In the past month, Chen Wei and Chen Xi have been sentenced to nine and ten years for “inciting subversion of state power,” in part for essays and articles they wrote online criticizing the political system in China and praising the growth of civil society. Zhu Yufu was indicted this month on subversion for publishing a poem online last spring that urged people to gather to defend their freedoms.

In Ethiopia Elias Kifle, an editor of a US-based opposition website, was sentenced to life in prison in abstentia and two journalists who covered banned opposition groups were sentenced and are now serving 14-year terms.

In the Cameroons Enoh Meyonnesse, author and founding member of the Cameroon Writers Association, has been held in solitary confinement and complete darkness for thirty days and denied access to a lawyer and has been sentenced to the harshest conditions for at least another six months.

Muhammad Bekjanov, Uzbek journalist and editor of the now defunct opposition newspaper Erk, had completed his twelve-year prison term, but this month was given an additional five years.

In Mexico reporter Raul Regulo Garza Quirino was gunned down by a gang and became the first journalist in Mexico murdered in 2012. In the past five years over 37 journalists and writers have been killed in Mexico and at least eight disappeared. Most reported on corruption and organized crime.

In India this month Salman Rushdie pulled out of the Jaipur Literary Festival after he was warned by intelligence sources that members of Mumbai’s criminal underworld had put a price on his head.

The redeeming news of the month comes from Myanmar, which still has an estimated 1000 political prisoners, including at least five writers, but the government has released poets, writers and journalists Win Maw, Zaw Thet Htwe, U Zeya and Nay Phone Latt and in late 2011 released Zarganar and lifted restrictions on Aung San Suu Kyi.

And in Vietnam blogger and university teacher Pham Minh Hoang was released, though numbers of writers remain in prison in Vietnam.

Each case has its own individual story, but all share the story of a writer writing what others feared and did not want read. Some cases are complicated by other circumstances, but many are surprisingly straight forward.

The case of Zhu Yufu began with the poem he wrote and posted at the time of the revolutions in the Middle East. The authorities took almost a year before they decided to prosecute him. Zhu’s lawyer said Zhu had nothing to do with the online calls for “the Jasmine revolution” in China; those calls began on overseas Chinese websites.

Below is Zhu Yufu’s poem “It’s Time”:

“It’s time, people of China! It’s time.

The Square belongs to everyone.

With your own two feet

It’s time to head to the Square and make your choice.

“It’s time, people of China! It’s time.

A song belongs to everyone.

From your own throat

It’s time to voice the song in your heart.

“It’s time, people of China! It’s time.

China belongs to everyone.

Of your own will

It’s time to choose what China shall be.

–by Zhu Yufu (translated by A.E. Clark)

Tourist in Beijing: A Dance with the Censor

We were five PEN members in Beijing, proceeding to Hong Kong where we’d been invited to celebrate Independent Chinese PEN Center’s (ICPC) tenth anniversary. It happened also to be the 90th anniversary of the Communist Party in China as large commemorative plaques proclaimed in Tiananmen Square. And it was the 90th anniversary of PEN International.

We were there to visit writers and book stores and any independent publishers we could find to gather information on the state of literature and freedom of expression in China and to show solidarity with threatened colleagues. Half the members of the Independent Chinese PEN Center lived in China, half outside. A number of ICPC’s members had been sent to prison for their writing, which the government deemed “subversive to the state.” The writing included articles challenging the demolition of old Beijing, food poisoning scandals and the lighting of 1000 candles commemorating Tiananmen Square. The most prominent of these imprisoned members was ICPC’s former president Liu Xiaobo, 2010 Nobel Laureate for Peace who helped draft Charter ’08 which set out a democratic vision for China.

Our first day—our recovery day—several of us visited the Summer Palace, Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City as well as a visit to an embassy. In the evening we gathered at a book store with writers and journalists where discussion focused on literature and the shrinking landscape for free expression. Micro blogging (like Twitter, though Twitter is blocked) was proliferating, we were told, and often skirted the censors, but censorship of the internet and traditional forms of writing had intensified.

In the days ahead writers, journalists, scholars and officials in embassies, all agreed that the crackdown on freedom of expression in China hadn’t been this grave since the days of Tiananmen Square. The restrictions since February (when the Arab spring began) included arrests of writers and human rights lawyers, torture, increased surveillance, closing down of events at bookstores and monitoring of all communications and movement of suspected dissidents. Many of the so-called dissident writers and human rights lawyers were so closely watched that police literally sat outside their doors.

On our second day the U.S. Embassy invited our delegation and 14 writers to a forum on freedom of expression. Only three of the fourteen writers showed up. The majority of the other invitees were visited or contacted by police and told not to come. The consequence of disobeying the police could be severe though the writers let us know they wanted to attend. While in Beijing every communication we had by phone or email had a push back, which meant our communications, or those of the recipients, were tracked.

At least six ICPC writers were warned and later blocked from attending the ICPC celebration in Hong Kong. This year China is spending more money (est. $95 billion) on its internal security than on its military budget.

For writing articles, individuals have been put in jail for years, charged with “inciting subversion against state powers.” An image I will take away is of one of the writers we met who had been imprisoned and tortured for writing an article that later became part of a larger public debate. He showed us pictures of himself in his small prison with his fellow prisoners as if he were showing us a family album. This had been his family for almost a decade. On the cover of his small photo album was a picture of Mickey Mouse.

(The night I flew out of China a major train crash on the high speed rail killed at least 39 people. Micro bloggers with over 28 million messages have challenged the censors and the state media as reports and comments on the accident buzz around the country. It will be worth noting who gets prosecuted first—those reporting the incident or those responsible.)

Ice Flows: Freedom of Expression

The Potomac River in Washington is frozen, though only with a light crust of ice, not like the Charles River in Boston which appears a solid block that one might stomp across all the way to Cambridge, though in the center a soft spot could crack open at any moment. Measuring the solidity of surfaces can be a matter of life and death.

The image of frozen surfaces arose as I was reviewing for a talk the appeals sent on behalf of writers in prison or killed for their work in the past year. Around 90 Rapid Action alerts (RANs) were sent out by PEN International, which tracks the situation of writers worldwide. I’d sent appeals on approximately half of these. I reviewed the risk and judgment of the writers in these countries. Some regimes were relentless; others, more arbitrary. Governments, like China and Iran, appear to be solid authoritarian regimes that brook little dissent, yet beneath the surface and at the edges, writers and others chip away, laying the groundwork for change that might yet crack open their societies.

The suppression of the writer is a barometer for political freedom in a country and can often be a predictor of events to come.

In July, the arrest of Fahem Boukaddous, a journalist sentenced to four years in prison for “harming public order” by covering demonstrations, foreshadowed both the recent suppression and the protests in Tunisia where the government’s crackdown on writers preceded the fall of the regime itself. Boukaddous and seven other writers have now been released.

In May, the arrests of Belarusian writers, including Vladimir Neklyayev, President of Belarus PEN, for “dissemination of false information” foreshadowed the sweeping arrests of writers, activists and opposition leaders during the presidential elections in December when Neklyayev and others were also candidates. It remains to be seen how the regime of Alyaksandr Lukashenko will hold, given the widespread charges of a flawed election and unrest in the population.

.

At the beginning of the year, the Chinese government detained and arrested writers, including Zhao Shiying, Secretary General of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Zhao protested the arrest and sentencing of fellow writer Liu Xiaobo to 11 years for his role in drafting Charter ’08, a document that called for democratic reform in China. The year continued with the detention of Chinese writers supporting Liu and democracy and also the arrests of writers in Tibet and the Uyghur Autonomous Region. If the suppression of writers is inversely proportional to freedom and democratic change in a society, then China remains at the top of the list of frozen governments.

The year also began with writers, journalists and bloggers in prison in Iran, followed by further crackdowns on writers, including Nasrin Sotoudeh. Sotoudeh, a writer and lawyer, was sentenced to 11 years on charges that included: “cooperating with the Association of Human Rights Defenders,” “conspiracy to disturb order,” and “propaganda against the state.” Other charges brought against writers in Iran included “congregation and mutiny with intent to commit crimes against national security,” “insulting the Supreme Leader,” “insulting the President,” and “disruption of public order.” The arrests, imprisonments and executions in Iran may give the appearance of a solid block of state power, but it is a block that may yet crack from the edges and the center as citizens continue to stomp across it.

It is worth remembering the precipitous fall 20 years ago of the Soviet Union as pressure for freedom sent fissures through the system that eventually broke the harsh authoritarian surface. As the world watches the current upheavals in the Middle East, one can track back and note the suppression of writers in Tunisia, Yemen and Egypt. The writers and their words are like a heat source that regimes try to trap beneath the surface but instead they soften up the ice.

“Because Writers Speak Their Minds”

50 Years of Defending Freedom of Expression

I’m staring straight into the sun lighting up the sky in shades of pink before it sets. I watch it slowly losing altitude behind a building near the World Bank. The yellow globe is sinking into the river, into the trees of Virginia across the Potomac. I am typing without looking at the page, my eyes fixed on the sun which I want to keep in the sky. For some reason I feel frantic to keep staring at the sun, hoping it won’t disappear. But in the time it has taken to write these few sentences, it has already lost half its sphere and is now only a diameter on the horizon. Soon it will be dark. I keep writing. I have just read Arthur Koestler’s “The Cell Door Closes” about his first moments in prison. Perhaps that is why I feel an irrational desire to keep this light in the sky, this sun from sinking…ah now it is but a sliver above the roof tops. How quick its descent once it finds the horizon, as if it wants to leave and go to the other side of the earth. And now it is gone. How long did that take? As long as it took to write this paragraph, this opening of a blog about the fiftieth anniversary of International PEN’s work for writers in prison.

Arthur Koestler was the first writer on whose behalf PEN successfully intervened. An earlier appeal on behalf of Frederico Garcia Lorca in 1937 arrived too late, and he was executed in Spain shortly after his arrest. But PEN’s advocacy for Hungarian novelist Koestler, also condemned to death in Spain, was noted when his captors released him.

In 1960 PEN founded a Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), which preceded the founding of Amnesty, to work on behalf of writers imprisoned, disappeared and killed for the expression of their ideas. Over the years PEN’s WiPC has defended writers around the world, including such well known ones as Josef Brodsky, Wole Soyinka, Breyten Breytenbach, Vaclav Havel, Ngui wa Thiong’o, Salman Rushdie, Aung San Sui Kyi, Ken Saro Wiwa and currently Liu Xiaobo and thousands of others.

For four years (1993-1997) I had the privilege of chairing that Committee. And the year of the fatwa (1989) against Salman Rushdie—a seminal event for anyone involved in freedom of expression work—I was president of PEN USA, one of the two PEN Centers in the US. During 25 years of working on freedom of expression, I’ve had the privilege of knowing and working with committed writers around the world who advocate on behalf of their threatened colleagues. It is a global network. If one were to map it, one would see intricate, criss-crossing corridors: writers in Poland working for writers in prison in Vietnam, writers in Ghana and Scotland taking action for the release of writers in China, PEN members in Australia and Germany and Italy working on behalf of writers in Cuba, writers in Mexico and Japan protesting the imprisonment and laws affecting writers in Turkey; members in Canada and the U.S. and Sweden speaking up for writers in Iran and Myanmar, writers in England and Norway for those in Belorussia. One can imagine hundreds of hands pushing up their bit of the sky to lift the horizon.

Failures as well as successes bind this network. In its fiftieth anniversary year, it is a tribute to the imagination which begins with imagining someone else. Imagination after all is the enemy of tyranny for it cannot be controlled.

From Arthur Koestler’s “The Cell Door Closes” from Dialogue with Death:

“It is a unique sound. A cell door has no handle, either outside or inside. It cannot be shut except by being slammed. It is made of massive steel and concrete, about four inches thick, and every time it falls to there is a resounding crash just as though a shot has been fired. But this report does away without an echo. Prison sounds are echo-less and bleak.

“When the door has been slammed behind him for the first time, the prisoner stands in the middle of the cell and looks round. I fancy that everyone must behave in more or less the same way.

“First of all he gives a fleeting look round the walls and takes a mental inventory of all the objects in what is now to be his domain:

the iron bedstead

the wash-basin

the WC

the barred window

His next action is invariably to try to pull himself up by the iron bars of the window and look out. He fails and his suit is covered with white from the plaster on the wall against which he pressed himself…..

And this is how things are to go on—in the coming minutes, hours, days, weeks, years.

How long has he already been in the cell?

He looks at his watch: exactly three minutes.”

Found in This Prison Where I Live: The Pen Anthology of Imprisoned Writers

Haitian Farewell

I met Haitian writer Georges Anglade, a bear of a man with a curly gray beard, in the Arctic Circle, in Tromso, Norway in 2004. He spilled a glass of red wine on me. We were at the opening reception of International PEN’s Congress, and whether we were moving in the same or opposite directions around the hors d’oeuvres table or he was gesturing with enthusiasm with his wine glass in his hand, I no longer remember; but the flow of wine down my black suit we both remembered every time we saw each other in the years that followed. It bound us in a moment of surprise and laughter and a kind of instant friendship as if I had been christened by him.

It was easy to be friends with Georges. He was warm, thoughtful and passionate about literature and language and about Haiti. He had come to the PEN Congress in Tromso to petition International PEN to establish a Haitian Center, which it did in 2008. Georges was the founding President.

Born in Haiti, Georges lived in Montreal, where for years he was a professor of social geography at the University of Quebec. He was also a vigorous defender of freedom of expression for writers, especially in Haiti, where he had been a political prisoner under the Duvalier regime. He visited Haiti as often as possible and was in Port-au-Prince when the massive earthquake struck on January 12. He was at a friend’s house, along with his wife of 43 years, Mireille Neptune. Neither Georges nor Mirelle survived. It is with deep sadness that I, along with colleagues around the world, bid Georges Anglade farewell.

Georges has been described by many friends as “a force of nature,” perhaps because of his grand size, his hearty laugh and his embrace of life. The force of nature which confronted him cannot really extinguish him. In his book Haitian Laughter, Georges wrote, “A people of laughter, they often say, justifiably astonished to see Haitians laugh in spite of their three hundred years of desperate situations; but do they know that it is precisely those three hundred years’ -wars that made them a people of lodyanseurs* [storytellers]….?”

Georges himself told these stories. The force of his life remains in his writing, in memory, and in the stories.

In an odd coincidence, the day of the earthquake, I was re-reading (as I do every decade or so) Graham Greene’s masterpiece, The Comedians, set in Haiti during the dictatorship of Popa Doc Duvalier. The novel embodies the nightmare, the passion and the love of the place. Speaking of his hotel Trianon, the narrator notes:

“I had grown to love the place, and I was glad in a way that I had found no purchaser. I believe that if I could own it for a few more years I would feel I had a home. Time was needed for a home as time was needed to turn a mistress into a wife. Even the violent death of my partner had not seriously disturbed my possessive love. I would have remarked with Frère Laurent, in the French version of Romeo and Juliet, a sentence that I had reason to remember:

Le remède au chaos

N’est pas dans ce chaos.

The remedy had been in the success…”

The world is now mobilizing to bring aid to Haiti. One can only hope that the attention and outpouring can restore and revitalize not only Haiti but the world that is for this moment at least coming together to assist.

[*lodyans are “brief, humorous stories, designates short, amusing tales at which Haitians are past masters and which are told at particular occasions (parties, evening gatherings, after a good meal…). The person who tells these lodyans is known by title of lodyanseur…”]

Yellow Geranium in a Tin Can

From the November/December 2009 Issue of World Literature Today as the Introduction to the Special Feature, “Voices Against the Darkness: Imprisoned Writers Who Could Not Be Silenced”

The prisoner Halil

closed his book.

He breathed on his glasses, wiped them clean,

gazed out at the orchards,

and said:

“I don’t know if you are like me,

Suleyman,

But coming down the Bosporus on the ferry, say

making the turn at Kandilli,

and suddenly seeing Istanbul there,

or one of those sparkling nights

of Kalamish Bay

filled with stars and the rustle of water,

or the boundless daylight

in the fields outside Topkapi

or a woman’s sweet face glimpsed on a streetcar,

or even the yellow geranium I grew in a tin can

in the Sivas prison—

I mean, whenever I meet

with natural beauty,

I know once again

human life today

must be changed . . .”

—Nâzım Hikmet, Human Landscapes (1966)

In 1938 the renowned Turkish poet Nâzım Hikmet (1902–63) was sent to prison, charged with “inciting the army to revolt,” convicted on the sole evidence that military cadets were reading his poems. He was sentenced to twenty-eight years but was released twelve years later in 1950. His “novel” in verse, Human Landscapes from My Country, was written in prison, featuring Halil, a political prisoner, scholar, and poet who was going blind (see WLT, October 2003, 78).

One of the cadets reading Hikmet’s poems was the young writer Raşit, who met the senior poet in prison. Raşit helped care for Hikmet, and Hikmet mentored Raşit, who went on to become famous in his own right as the novelist Orhan Kemal. The friendship of the two men endured past prison, as Maureen Freely’s article “The Prison Imaginary in Turkish Literature” (page 46) chronicles.

In this issue of WLT, stories, essays, and poetry from Turkey, Burma/Myanmar, Iran, South Africa, Libya, and Iraq show prison as a cage, a crucible, a classroom, a stage, a fraternity from hell. The challenge for the writer in prison is to survive and to keep writing.

Governments have long tried to stifle dissent by imprisoning the writer. The charges vary: “inciting subversion of state power,” “insulting religion,” “insulting the president,” “insulting the army,” “spreading false news.” Today the largest number of writers in prison for the longest periods are in China, Burma/Myanmar, Cuba, Vietnam, and Iran. In some countries such as Mexico and Russia, the threat to writers is assassination, often by criminal elements who operate with impunity. In Latin American countries such as Colombia, Peru, and Honduras, death threats are serious inhibitors to free expression. In many African countries such as Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, and the Gambia, violation of criminal defamation laws—particularly those relating to “insulting the president”—can land a writer in prison. Worldwide, the increasing use of anti-terror legislation has resulted in imprisonment of writers when the line blurs between legitimate dissent and criminal advocacy of terror and violence as in Spain and Sri Lanka. In the United States, writers are rarely imprisoned for their writing, but over the years the U.S. government has denied visas to writers from other countries whose political views the authorities object to.

The texts in this issue are from writers who were locked up for political reasons in some of the harshest prisons by authoritarian governments on both the left and the right. Common among the jailers was not their politics, but their fear of opposing opinion. Implicit was the belief that the writer and his words could undermine the authority of the state.

For a generation of Turkish writers, prison was almost a rite of passage as the government incarcerated anyone suspected of communist or leftwing sentiments. Conditions in prison were harsh, but Nâzım Hikmet insisted that the writer must master his despair in order to pursue his literature. Hikmet committed himself to his fellow prisoners, tutoring them and learning from them. He warned the younger Raşit about the corrosive effects of despair: “Beware, my son, protect yourself from this, be even more bitter and sad, but let your joy and hope shine through.”

As seen in these texts, the writer’s imagination and the support of fellow prisoners and those outside the prison penetrate the despair and allow hope to struggle through so that the spirit endures and literature survives. The story “Life on Death Row” (page 52) chronicles how the prisoner’s life in Myanmar shuts down to a small, dark space, but also how the prisoners “boosted spirits by singing” and relating books to one another.

In “Seven Years with Hard Labour: Stories of Burmese Political Prisoners” (page 55), Sara Masters recounts the experiences of writers who have served and are serving in the infamous Insein prison in Myanmar. She also tells of people outside the prison and the country who give voice to those locked up or shunted to the margins. Through theater and film, Actors for Human Rights and the iceandfire theater company render the humanity, humor, and tragedy of the Burmese, which the government would hide away.

In U Win Tin’s poem “Fearless Tiger” (page 43), the narrator’s courage and endurance spring from his certainty that truth, the people, time, and God are on his side: “Like a tiger in the zoo, / Rolling in a cage. / Do they think it has become harmless? / […] / It’ll always be a fearless tiger. / Just like me.” U Win Tin spent nineteen years in Burma’s Insein prison.

Iraqi poets Saadi Youssef and Amer Fatuhi (pages 60-61), imprisoned at the beginning and end of the Baathist regime, both use the tools of the imagination to assault the darkness.

Tunisian writer Omar Al-Kikli’s stories “Awareness” and “The Technocrat” (page 51) show a writer in harsh conditions—in his case, ten years in a Libyan jail—still finding in the life around him the beauty that helps him endure. “For the first time, he could see the clear sky with a mixture of delight and suffering. He wondered why he hadn’t recognized the splendor before no….He wished that he could take, from the sky, a blue fragment abundant with clarity and brightness and keep it with him.”

The challenge of captivity and freesom is not simply political. In “The Inextricable Labyrinth” (page 45), Breyten Breytenbach shares the existential dilemma he faced when the society that imprisoned him changed. Proud to be “a statutory, convicted terrorist” in apartheid South Africa, Breytenbach finds himself trapped as a free man by respectability and responsibility. “I have seen. I am responsible. I must report….And here I am now, writing myself, burrowing into an inextricable labyrinth.”

Iranian filmmaker Nahid Persson Sarvestani (page 57) highlights the importance of the witness to tell the story. In an interview, Sarvestani explains her compulsion to film the struggle of the people in Iran, particularly women, who are bound by repressive laws. Imprisoned under house arrest herself, Sarvestani notes that after the recent presidential election, Iranians “could not be quiet any more. Despite the fact that the regime imprisons, tortures, and executes young people in order to keep others quiet and under control, people will not be silenced or stopped.”

Sixty years ago Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserted: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” A number of signatories who subsequently imprisoned writers signed this declaration, including Turkey, Burma, Cuba, Iraq, and Iran, represented here.

Article 19 set the standard for freedom of expression in the last half-century. Though its full realization has not yet been achieved, its ideal reflects the dream of Hikmet’s narrator in the opening poem that “human life today must be changed.”

A number of the writers represented in this issue were released from prison early, in part because of pressure from those outside who advocated on their behalf. With the combination of a megaphone for the writer and a klieg light on the abuser, organizations such as PEN, the Committee to Protect Journalists, Reporters Without Borders, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and others lobbied governments and mobilized international institutions and citizens to uphold the right for individuals to speak and write freely.

Readers of this “Voices Against the Darkness” section can celebrate the writers and the writings that have survived, rather like a yellow geranium growing in a tin can.

To read other prison literature featured in this issue of World Literature Today, go here.

“There Will Still Be Light” *

In August, 1993 in Myanmar (Burma), Ma Thida, a 27-year old medical doctor and short story writer was arrested and sentenced to 20 years in prison, charged with “endangering public tranquility, of having contact with unlawful associations, and distributing unlawful literature.” She had been an assistant to Aung San Suu Kyi and traveled with Suu Kyi during her political campaign.

In September that same year at the International PEN Congress in Spain, I stepped into the Chair of International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. One of the early main cases that came across my desk was that of Ma Thida.

Last week in Providence, Rhode Island Ma Thida and I shared a stage with others at Brown University in a program: There Will Still Be Light: a Freedom to Write Literary Festival focused on the situation in Burma today as well as the situation for the freedom of writers around the world. For the past year Thida has been at Brown as a fellow of the International Writers Project (a joint appointment of the Writing Program and the Watson Institute for International Studies) which gives a writer under stress a year to work and to share their work and cultural heritage.

Thida and I had met before in London soon after she was released from prison– five years, six months and six days, mostly in solitary confinement–after writers around the world had protested and written letters on her behalf as had those in other human rights organizations. No one knows for certain what levers prompt a government to release an individual so no organization can ever claim the success, but it is clear that pressure from many sources, voices from around the globe, individuals in countries on every continent caring and imagining the fate of their colleagues and acting on that does contribute.

It is a thrill and one feels deep humility when actually meeting the person who has endured, and who, up until that point, has only been represented by words on paper. In Thida’s case as I searched old files, I found fading words on fading fax paper, verses of her poems and parts of stories clandestinely translated and smuggled out by a British official, who was also at the literary festival last week.

Earlier this week another writer Liu Xiaobo, who is under house arrest in China, was honored by PEN American Center’s Freedom to Write Award. Liu Xiaobo is one of the drafters of the Charter 08 manifesto which urges democratic reform in China. He is a well-respected literary critic and writer and former president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. A worldwide campaign for his release is ongoing. One hopes for the day when we might also meet Liu in person. Right now he can be seen and read and heard–no longer on fading fax paper–but on the internet and on You Tube.

The technology of the globe has changed considerably since Ma Thida was imprisoned, but thought has not progressed as rapidly. Recently I was in a meeting in Washington on Capitol Hill relating to human rights and an individual said, “I can’t be worried about a few poets in prison.” The statement wasn’t meant to be callous; the speaker was aware of the complexity of problems in places like Burma and China and of the competing policy needs. The view, which was perhaps intended to sound practical and experienced, is at best short-sighted and at worst dangerous.

As policy is being crafted to try to assist in opening up Burma and China, to increase the space for freedom, to end the abuses of torture and long term imprisonments, as questions of sanctions versus trade, engagement vs. isolation, questions of real politic are debated, let us not forget the poets–and the short story writers, the novelists, the critics, and the journalists–who are on the front line of ideas and therefore often imprisoned. They are among the citizens who will do the opening up in these countries; they are the citizens who live there.

Supporting voices of citizens around the world can help, but it is “the few poets in prison” who will be among those who prepare the lamp and light it and carry it on.

* if the moon does not shine

and the twinkles of the stars are faint

the lamp will be prepared

at the entrance to the house

there will still be light

— from “The Road is Not Lost” by Burmese poet U Tin Moe (1933-2007), imprisoned in Burma from 1991-1995

Charter 08: Decade of the Citizen

Grandstands are rising around Washington, DC. The U.S. is preparing for the Inauguration of a new President whose campaign mobilized a record number of citizens and focused on themes of hope and change.

Half way around the globe in the world’s most populous country, a relatively small group of citizens are proposing radical change for their nation, change which reflects in large part the ideals upon which the United States was founded. However, the proponents of this change have been interrogated and arrested.

On December 10, the 60th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 300 leading mainland Chinese citizens—writers, economists, political scientists, retired party officials, former newspaper editors, members of the legal profession and human rights defenders–issued Charter 08. Charter 08 sets out a vision for a democratic China based on the citizen not the party, with a government founded on human rights, democracy, and rule of law. Charter 08 doesn’t offer reform of the current political system so much as an end to features like one-party rule. Since its release, more than 5000 citizens across China have added their names to Charter 08.

Before the document was even published, the Chinese authorities detained two of the leading authors Liu Xiaobo and Zhang Zuhua and have since interrogated dozens of others who signed. Most have been released though they continue to be watched. However, Liu Xiaobo, a major writer and former president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, remains in custody with no word of his whereabouts and fears that he will be charged with “serious crimes against the basic principles of the Republic.” The Chinese government has also blocked or deleted websites and blogs that carry Charter 08.

Charter 08 was inspired by a similar action during the height of the Soviet Union when writers and intellectuals in Czechoslovakia issued Charter 77 in January, 1977. Charter 77 called for protection of basic civil and political rights by the state. Among the signatories was Vaclav Havel, who was imprisoned for his involvement but went on to become the President of the Czech Republic after the Soviet Union ended.

Citizens around the globe, including Vaclav Havel, Nobel laureates, human rights defenders, writers, economists, lawyers, academics, have rallied in support of those who signed Charter 08. The European Union has expressed grave concern at the arrest of Liu Xiaobo and others. Petitions in support of Charter 08 and in protest over the detention of Liu Xiaobo are circulating around the world.

The arrest of Liu Xiaobo happened on the eve of Human Rights Day and the 60th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The year 2008 is also the 110th Anniversary of China’s Wuxu Political Reform, the 100th Anniversary of China’s first Constitution and the 10th Anniversary of China’s signing of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the soon-to-be 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown against students.

Charter ’08 is well worth reading. It sets out the political history of China in its forward, then proposes fundamental principles–freedom, human rights, equality, republicanism, democracy and constitutional law—upon which the government should be based. The document advocates specific steps–a new constitution, separation of powers, legislative democracy, independent judiciary, public control of public servants, guarantee of human rights, election of public officials, rural-urban equality, freedom to form groups, freedom to assemble, freedom of expression, freedom of religion, civic education, protection of private property, finance and tax reform, social security, protection of the environment, a federated republic, truth and reconciliation.

Charter 08 lays forth an ambitious agenda, one that would revolutionize the political climate and governing structures of China, but it advocates for change not through violence, but through citizen participation. Is this naive? Foolhardy? Or is this vision for China one that will inspire and empower its citizenry?

“We dare to put civic spirit into practice by announcing Charter 08,” declare the signatories. “We hope that our fellow citizens who feel a similar sense of crisis, responsibility, and mission, whether they are inside the government or not, and regardless of their social status, will set aside small differences to embrace the broad goals of this citizens’ movement. Together we can work for major changes in Chinese society and for the rapid establishment of a free and constitutional country.”

As citizens in the U.S. prepare to inaugurate a new President, the first African American President, the country is not so much realizing change as realizing in its electoral process the ideals set forth over 200 years ago.

Ideas may be repressed for a time and their authors may be persecuted, but ideas and words matter. Eventually they are the fuel for the engine of change. Those who have the courage to set them down and publish them may turn out to be the founding fathers on whose shoulders generations will stand.