Posts Tagged ‘Diyabakir’

PEN Journey 34: Diyarbakir and Beyond—Finding Byways for Peace

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN has always been about building bridges, finding the byways of fellowship among writers whose currency is language and imagination and whose hope is that even with radically different histories and backgrounds, writers might find a way to sit down across a table from each other and share stories and listen to each other and thereby have a beneficent influence on the way they and their societies see themselves and others.

It is an idealistic goal that has been battered in PEN’s hundred year history, and yet the organization continues; the dialogues continue, and writers from over 100 countries continue to meet and talk, even from countries whose governments have not found peace in decades. There have been moments of seeing that optimism realized, at least for a time, and also seeing it smashed.

The next section of these PEN Journeys covering the years 2004 (PEN Journey 33) through 2007 (August) will focus on my years as International Secretary of PEN International. I will travel through events chronologically, the number of events increasing considerably as the role demanded. I will try to knit these together as we continually try to do as an organization.

International PEN Seminar on Cultural Diversity in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005

In January, 2005 we held our first board meeting of the year in Vienna where PEN President Jiří Gruša had recently taken up the position as Director of the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna which hosted us. The formal board meeting itself took place in the basement of the hotel restaurant where we were staying. Around the table in the cozy space where we sat on chairs and on a long booth was PEN’s diverse board from Algeria, Colombia, France, USA, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Croatia, Australia, Norway and Japan. The search for an executive director, the new financial and employment systems going into place in the office, an upcoming meeting in Stavanger, Norway with the old Cities of Asylum Network, and an upcoming meeting in Diyarbakir, Turkey with Kurdish and Turkish PEN—all populated the agenda as did the omnipresent discussions on fundraising.

For me, the imminent departure of my Marine son from the combat zone in Iraq hovered in the corner of my mind. We were staying at a pension hotel with small rooms—single bed, dresser and nightstand; I could almost touch the walls on both sides. Outside it was snowing. I’d come to Vienna unprepared for the snow and had bought at a sale a large puffy yellow coat that now draped across the bed for warmth. At night in the dark as I fell asleep, I thought about my son and one night dreamed a desperate dream. Then the phone rang; it was 1:30 in the morning. My husband’s voice woke me. “Wheels are up!” he declared. “They are on their way home!” I still remember the moment, lying there in the dark, snow glistening in the light through the small window and feeling as though the walls had suddenly expanded and a weight lifted that I hadn’t been fully aware I was carrying. The memory…the snow, the Cathedral we passed each day in the square and at dusk in the evening, the puffy yellow coat…

I was wearing that same coat as snow fell later that month in Washington, DC the day my son finally pulled into our driveway. I was sitting on the front porch swing in the snow waiting for him, thinking about the hotel room in the dark, the restaurant basement where we helped craft a conference for writers from the hostile parties in Turkey and another to find sanctuary for writers fleeing oppression—all these memories are wrapped together in a moment of return and of the spirit lifting and life opening a corridor to walk down.

Czech PEN 80th Anniversary in Louvre Cafe where PEN members met in 1925. L to R: Playwright Tom Stoppard, PEN Int’l President Jiří Gruša, Czech PEN President Jiří Stránský.

The next meeting I attended that winter on February 15, 2005 celebrated the 80-year anniversary of Czech PEN. In Prague Jiří and I toasted the endurance of his PEN Center which had been founded by Karel Čapek and 37 Czech writers on that day in 1925. Czech PEN had survived the Second World War, the Cold War, the Soviet occupation and finally the liberation. Former prisoner, playwright and PEN member Václav Havel had become President of the country and his good friend and also prisoner Jiří Gruša was now President of International PEN. Under the auspices of the Minister of Culture, we met with Havel and playwright Tom Stoppard, himself Czech, and Jiří Stránský, President of Czech PEN at the Louvre Café where the original PEN gathering had taken place. Later, the Mayor of Prague hosted a reception with Czech PEN members in the Old Town Hall where he opened an exhibition celebrating “Eighty Years of the Czech PEN Club.”

The following week Writers in Prison Director (WIPC) Sara Whyatt and I traveled to the city of Stavanger, Norway which sat on the sea with a harbor and ships at dock. The Stavanger meeting brought together PEN and members of the now disbanded International Parliament of Writers, an organization founded after the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. The Parliament of Writers had developed a program to house writers in cities of asylum, but the Parliament of Writers no longer functioned. Many of the cities, however, still wanted to continue their hospitality for writers at risk. Stavanger itself hosted writers, including poet and novelist Chenjerai Hove, who’d been president of Zimbabwe PEN until he’d had to flee the government of Robert Mugabe. Hove was a fellow at the House of Culture in Stavanger until he passed away in 2015.

Stavanger, Norway, February, 2005 setting for birth of International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN)

Helge Lunde, director of the Stavanger International Festival of Literature and Freedom of Speech convened PEN, representatives from the old Parliament of Writers and representatives from some of the cities that wanted to continue the program. In a several day meeting, the outlines of what would become the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) were laid down with PEN as the vetting organization for applications and also a source of hospitality when writers arrived in their new temporary homes. ICORN remains active today in partnership with PEN in over 70 cities which promote and protect freedom of expression and host writers and artists at risk by providing housing, an income, literary arenas, scholarships and grants. PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and ICORN regularly hold biennial meetings together.

Writer Liu Binyan, a founder and first President, Independent Chinese PEN Center

The following weekend at Princeton University the relatively new Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), founded in 2001, honored Liu Binyan, one of its founders and first President. ICPC’s members live both in China and abroad. The PEN Center gave them the ability to talk with each other and hold programs together, often in Hong Kong. Because of his writing and criticism of the Chinese Communist Party, especially after Tiananmen Square, Liu Binyan had not been allowed to return to China after an academic stay in the U.S. Though he never saw China again, in the U.S. he wrote and worked as Director of Princeton University’s China Initiative. (Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo was also a founder of ICPC and its second president.) At the dinner at the Princeton Faculty Club, ICPC members and China scholars presented Liu Binyan the book Living in Exile, written by distinguished essayists in China and abroad and dedicated to Liu who had spent considerable time in detention and in and out of labor camps. Later that year Liu Binyan passed away at his home in New Jersey.

In March “The International PEN Diyarbakir Seminar on Cultural Diversity” convened the largest and most ambitious conference that quarter in the primarily Kurdish southeast of Turkey. For years the Writers in Prison Committee had focused on cases in this dangerous region where fighting between the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and the Turkish military had resulted in multiple imprisonments and killings. However, a rapprochement appeared to be expanding between the government and Kurdish citizens. In this space, PEN International had been working with Kurdish PEN and Turkish PEN to prepare this historic meeting of the two centers, along with PEN’s leadership of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC). For the first time Kurdish writers and Turkish writers would speak side by side from the same stage in Kurdish and Turkish with translations of each language.

Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jane Spender (PEN International Program Director), Carles Torner (Vice Chair Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee).

My predecessor as International Secretary Terry Carlbom had been instrumental in the planning, and we all agreed he should continue as coordinator of the seminar. Seventy delegates from a dozen countries gathered in the ancient city of Diyarbakir/Ahmed for five days. Diyarbakir dated back at least 5000 years, one of the oldest cities in the ancient land of Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Later it was dominated by Persia and by Alexander the Great. Because of its strategic position, Diyarbakir’s sovereignty changed many times, was part of the Roman empire, later conquered by the Arabs in 639, by Tamerlane in 1394; the Ottomans conquered in 1515. Diyarbakir continued through cycles of battles for control.

Old Diyarbakir was a standard Roman town circled by a wall, the stones of which still stood. The black basalt wall was said to be second only to the Great Wall of China. Within the walls a labyrinth of cobbled streets and alleyways unfolded, leading to towers where we could see the rivers and gardens and the city’s mosques and street life below, where caravan travelers used to stop on the silk road.

Before the conference began, PEN International Program Director Jane Spender and I explored the twisting paths and shared black tea in a central plaza with Carles Torner, vice chair of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee. As an American whose national history extended back barely 400 years, this accumulation of history in the streets and walls and buildings was mind-bending. In stones, in ideas…where did history reside and how did it evolve?

On the first evening Diyarbakir’s Lord Mayor Osman Baydemir greeted us at the Town Hall for a Newroz (New Year’s) reception. I thanked him on behalf of PEN for all he and the city had done to support this seminar. “It is a treat for us to visit one of the world’s oldest cities, with a history that could occupy the imagination of a community of writers like us for years to come,” I said. “Central to the Charter and ethos of PEN is a celebration of the universal which binds us as human beings and of the diversity which distinguishes each individual—the specific history, language and culture. It is our challenge and our aspiration as writers and members of PEN to provide the forums where cultures don’t clash but communicate. That is what we hope to do here in Diyarbakir.”

The first full day of the seminar we spent at the Newroz Festival. Our delegation was seated in an honored place in the bleachers which turned out to be behind the mother of Abdullah Öcalan, one of the founders and leaders of the PKK who was currently in prison. On the grounds in front of us spread thousands/ hundreds of thousands—some said a million people—celebrating the Kurdish new year, a time that coincides with the March equinox. Terry Carlbom and I were soon escorted to the main stage where we stood looking out over a sea of people as far as we could see, many in colorful local dress. Because PEN is specifically a nonpartisan/nonpolitical organization, we felt some ambivalence at the appearance of being swept into the Kurdish cause; on the other hand, the experience was one I won’t forget. The day was celebratory without violence. If there were political speeches, they were not translated for us, and we were accompanied by our Turkish colleagues who also attended.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference on Cultural Diversity, 2005. L to R: Mehmed Uzun and Dr. Zaradachet Hajo (Kurdish PEN), Kata Kulavkova, (Chair, PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Secretary), and Üstün Akmen, Turkish PEN

That evening in opening the conference, I noted, “In Diyarbakir/Ahmed this week we’ve come together to celebrate cultural diversity and explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.”

The official program began with the Lord Mayor and the President of Kurdish PEN Dr. Zaradachet Hajo and the President of Turkish PEN Mr. Üstün Akmen and a keynote speech by Kurdish author Mehmed Uzun. The following evening Turkish writer Murathan Mungan delivered an introductory address to a public gathering.

At the conference itself Kurdish and Turkish writers, poets, publishers and translators shared history and literature across their linguistic borders. Through discussion and readings and performances, they addressed the importance of cultural diversity as a value in a culture of peace.

Renowned Turkish/Kurdish novelist Yaşar Kemal, former president of Turkish PEN, had been invited but was ill and sent a message instead. He noted that the world was going through a difficult period and was faced with terrible destruction. He asked, “What makes human beings? Love, compassion, peace, friendship…Human beings are the only creative beings in the world.” Local cultures are being destroyed and with that is the destruction of languages and art and values, he said. In life and death we have to stand against a terrible destructive force in favor of local and national culture. “I believe your meeting will be successful,” he predicted.

Kata Kulavkova, Chair of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee emphasized the importance of the capacity to imagine, the importance of cultural memory and openness to dialogue. “Europe needs all identities, including Kurdish identities,” she said, noting that every culture is the center of the world for itself. “Turkish and Kurdish culture depend on each other to promote Turkish/Kurdish universal culture.”

Hüseyin Dozen of Kurdish PEN noted that literary translation helps a language to flourish; languages that are not standardized are enriched by literary translation which is an art rather than a scientific discipline. As far as languages that have no official status or have been prohibited, oral literature plays a central role, and the work of a translator must not neglect this kind of literature in his work.

PEN Vice President Lucina Kathmann led a discussion on “Bridging Borders” among women writers. Müge Sökmen of Turkish PEN moderated a discussion on Diversity and Literary Translation; Kurdish PEN member Berivan Dosky moderated a discussion on Cultural Diversity and Peace; Turkish PEN’s Vecdi Sayar led the discussion on Cultural Diversity and Dialogue, and Aysu Erden of Turkish PEN moderated a panel on Cultural Diversity and Linguistic Diversity.

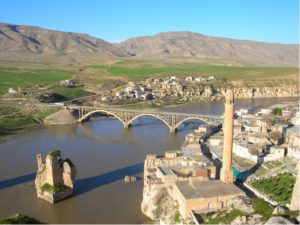

PEN trip to ancient town of Hasenkeyf, Turkey, 2005 including PEN International and Turkish and Kurdish members

One of the highlights of the conference was a visit to Hasankeyf, reputed to be the oldest continuing settlement on the planet and a cradle of civilization. Built into the sandstone cliffs in southeast Turkey, Hasankeyf had yielded relics that dated the site even earlier than the 12,000 years recorded, perhaps as old as 15,000 years. This Kurdish town of southeast Anatolia was threatened by a dam the Turkish government planned to build on the Tigris River. The Ilisu Dam would drown the town as the water was diverted and eventually would submerge Hasankeyf under as much as 400 feet of water.

Lunch in a cave in Hasenkeyf, 2005, including PEN International representatives Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Jane Spender and Lucina Kathmann

As we journeyed up the stone steps to the ruins of Hasankeyf Castle and later as we ate lunch in a cave, then bought small souvenirs from children who lived in the town, our delegation fell in love with the setting and the people. Several of us returned home and began writing about Hasankeyf in an effort to preserve its heritage. We were not alone. Worldwide protests to save this ancient site had been lodged, and the dam had been delayed. I set a google alert so that every time there was mention of the Ilisu Dam, I would know. Lucina Kathmann and I began exchanging latest news.

In spite of worldwide protests, the giant Ilisu Dam was completed after many delays in July, 2019. It began to fill its reservoir, tapping water from the Tigris River and diverting it from Iraq. The rising water levels are now slowly submerging the town of Hasankeyf, flooding the area which had been settled for millennia. The population for the most part has had to move. The waters have risen 15 meters and continue to rise around 15 centimeters per day, according to a February report by Reuters.

Hasenkeyf, Turkey, March 2005 during PEN Conference on Cultural Diversity, before the Ilisu Dam flooded the region.

Turkey’s rapprochement with the Kurds has also taken a turn away from the opening and the cultural diversity we celebrated in the 2005 Diyarbakir Seminar. But literature was exchanged there; friendships were made, and the dialogue among PEN members continues. Individual by individual has always been the strength and the modus operandi of PEN.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 35: Turkey Again: Global Right to Free Expression

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

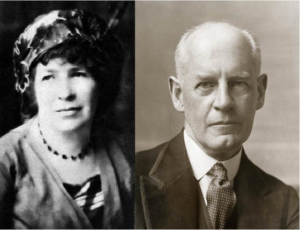

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference, March 2005

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through 141 centers in 99 countries. They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see this ancient city for himself, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together. –Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International