Posts Tagged ‘freedom of expression’

Life instead of Death…Rationality instead of Ignorance

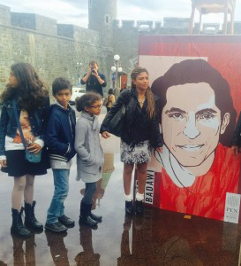

Of all the lively discussions, the literary evenings, multiple resolutions generated at PEN International’s 81st Congress last week in Quebec City, the image that stays in my mind is of the petite wife and children of Saudi blogger and editor Raif Badawi standing in a puddle on the plaza by his picture in the early morning, along with delegates from PEN centers around the world.

His wife and children now live in Quebec, which has also offered Raif Badawi a home, but he remains in a Saudi prison with a ten-year sentence and 950 more lashes of punishment, then a decade long ban on travel, all for setting up a digital forum to encourage social and political debate within Saudi Arabia. He has been found guilty of “insulting Islam” and “founding a liberal website.”

The PEN Congress, which hosted writers from 84 centers in 73 countries, featured three writers with “empty chairs,” including Raif Badawi, Eritrean poet, critic and editor Amanuel Asrat and murdered Honduran journalist Juan Carlos Argenal Medina. PEN called for the release of Badawi and Asrat and justice for Medina. It also targeted the cases of writers imprisoned, threatened, killed or at risk in Bangladesh, China, Cuba, Eritrea, Honduras, India, Iran, Mexico, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Tibet, Turkey and Vietnam.

Badawi’s message via his wife to PEN members after receiving an earlier PEN Canada One Humanity Award was: “We want life for those who wish death to us, and we want rationality for those who want ignorance for us.”

What Are You Not Reading This Summer?

I was recently sent a questionnaire as part of a profile asking me what I was reading:

I find myself reading several books at the same time. I just finished Phil Klay’s Redeployment today, am reading Jennifer Clement’s Prayers for the Stolen, am re-reading Graham Greene’s The Comedians, re-reading Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this and can’t leave this question without noting Elliot Ackerman’s Green On Blue. Because I read both e-books and paper books, I move around among narratives easily.

The answer was a snapshot in reading time, indicative of the pleasure of dancing among narratives. I find myself enjoying on several platforms the movement between hard-edged, nuanced stories of war and its aftereffects in Klay’s Redeployment and Ackerman’s Green on Blue, the harsh and surprising world of Clement’s indigenous Mexican women in Prayers for the Stolen and the gentle, but no less desperate stories of Southern women trying to find their lives in Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this, a collection recently re-published by a new small press—Bacon Press—in paperback. Graham Greene is a master who I am always re-reading, appreciating how he integrates the international world of politics and deceit with compelling narratives set around the world.

Recently I returned from PEN International’s biennial Writers in Prison conference and the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) meeting, a gathering this year in Amsterdam focused on Creative Resistance, a gathering of over 250 individuals from 60 countries around the world who work on behalf of writers threatened, imprisoned and killed for their writing. I remain conscious of these voices too. They occupy a kind of negative space—those we are NOT reading, not able to read because they are not able to write.

The list unfortunately is long, and many individuals stand out for me, but I will highlight two here. Though I couldn’t read either because of language differences, I read with attention their cases and link here to actions that can be taken on their behalf:

—Raif Badawi, a blogger and editor in Saudi Arabia, had his sentence confirmed this past week by the Supreme Court that he must serve 10 years in prison and receive 1,000 lashes for “founding a liberal website,” “adopting liberal thought” and for “insulting Islam.” Raif had planned a conference to mark “a day of liberalism,” and he launched an online forum, Liberal Saudi Network to encourage political and social debate. His lawyer has now also been arrested.

His wife, who fled with their three children, says she received threats from the Saudi embassy when she was in Lebanon that they would kidnap her children and forcibly return them to Saudi Arabia; the court verdict would force her to separate from her husband.

Though now living in Canada, she says, “I believe that there is a will for freedom in the country that will not be deterred.” Of the solidarity movements that support her husband, she adds in an interview with PEN International, “I used to believe it was a fantasy for a person to stand in support of another person regardless of geographical, racial, religious, linguistic and other differences, but what you have done for Raif’s case has taught me that I knew nothing about humanity.”

Link for more information and action.

—Gao Yu–Chinese journalist, former chief editor of Economics Weekly and contributor to the German newspaper Deutsch Wele and a poet–was arrested on charges of illegally obtaining state secrets and sharing them with foreign media and sentenced this spring to seven years in prison. When she was first disappeared, she was writing a column entitled ‘Party Nature vs. Human Nature,’ which is said to have considered the new leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and its internal conflicts. Gao Yu, who is 71, has been an intrepid journalist her whole career and an honorary director of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. She has often been at PEN conferences in Hong Kong and contributed to an essay in PEN’s 2013 report “Creativity and Constraint in Today’s China.”

She has served time in prison before, the first time for reporting on student protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and five years for reporting on political and economic issues in Hong-Kong based publications. She’s known for her critical political analysis of the inner circles of the Chinese Communist Party. Her arrest and sentencing has signaled to many the retreat from hope of wider press freedoms under the new leadership.

For those of us lucky to have met Gao over the years, we’ve seen she has a sharp mind, a smiling face and an unmistakable light in her eyes as though she is slightly amused and looking at a much longer narrative for China. At the recent PEN conference, each meeting had an empty chair on the stage, and a picture of Gao Yu as the honored writer not there.

Link to more information and action.

PEN Pregunta: Corruption, Violence, Impunity: What Can Writers Do?

PEN International and its Latin American and North American PEN Centers gathered this past week in Central America and in Mexico City for the third PEN Americas Summit to address the challenges to freedom of expression and the crimes against writers. The region, in particular Mexico, is one of the most dangerous in the world for writers and journalists who are killed, disappeared, attacked and threatened with virtual impunity.

In Mexico over 100 journalists have been murdered since 2000; 25 have been forcibly disappeared and hundreds are attacked and threatened each year while their attackers remain free.

During the Summit PEN identified the structural issues impeding freedom of expression, including the weakness within the Office of the Special Prosecutor for Crimes Against Freedom of Expression, the use of criminal defamation laws, the barriers to entry and lack of diversification within the Mexican news media, the close relationship between much of the media and the Mexican government and the manipulation of advertising payments from the government to media as a reward for positive coverage.

Developing recommendations, PEN officials followed up by meeting with government ministers. Most important the writers in the region will follow up with each other advancing the narrative in their countries which included Argentina, Brazil, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Canada, and the U.S

The Summit ended in Mexico City with a public Pregunta,—a brief statement and question from each of the participants to generate discussion.

Question: What can a gathering of writers do in the face of killings, disappearances and attacks on journalists in Mexico?

Question: What can a gathering of writers do in the face of killings, disappearances and attacks on journalists in Mexico?

Writers’ tools are words and narrative. The narrative in Mexico has deteriorated with journalists and writers attacked at a rate of almost one a day and many killed while their attackers live with impunity. What can a room of writers do? We can begin by helping change the narrative.

PEN was founded by writers in Europe after World War I who wanted to charge the narrative of nationalism that had led to that war.

In my years working in PEN, I have witnessed societies change and freedoms expand, in part because writers and journalists advanced the narrative of the individual’s right to free expression, the right to imagine different societies and to live without fear.

When I began in PEN, South Korea had prisons filled with writers. That is no longer the case. Czechoslovakia had major writers in prison as did most of Eastern Europe. Societies can change. Writers can help lead the way inspiring and re-imagining the narrative until it becomes reality.

Today much discussion is about the brutality of ISIS. The brutality—the beheadings, murders, disappearances—that are happening in Mexico are not a global focus. Today we can witness and bring focus and help re-imagine the outcome.

Question: What can writers do in the face of killings, disappearances and attacks on journalists? Please share your ideas below.

PEN on the Plains of Central Asia

PEN International’s 80th Congress opened with galloping horses across the majestic plains of Central Asia’s Kyrgyzstan this past week when the 200 plus delegates from 73 PEN centers around the world encountered “Kurmanjan Datka: Queen of the Mountains” the epic new film featuring Kyrgyzstan’s national heroine. The cinematically stunning drama spanned the late18th to 19th century when the modern nation formed, led by a woman—wife, widow and mother—in a time when women had no rights, when enemies threatened on all sides. The drama ended with Russia’s annexation of the region.

A hundred years later PEN delegates gathered in Bishkek for PEN’s annual Congress whose theme My language, my story, my freedom included discussion, debate and advocacy on issues of free expression. PEN called for release of Uzbek writer Azinjon Askarov from a Kyrgyz prison, Vladimir Kozlov from Kazak prison and Ilham Tohti, who was recently given a life sentence in China for alleged “separatism.” These three individuals were featured with empty chairs at the Congress and represented the more than 900 writers, journalists, publishers, editors and bloggers listed in PEN’s case list and for whom PEN advocates.

Kyrgyzstan is considered the freest of the Central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union, the only republic that could have hosted a PEN Congress, but it is still challenged with ethnic conflicts and with repression of certain minorities, including those from the LGBT communities. The influence of the Russian Federation, including its Law of False Accusation and criminal defamation and laws against “gay propaganda,” the influence of radical Islam and ethnic conflicts affect free expression in the country, according to Marian Botsford Fraser, the Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee.

Before the Congress, PEN International’s President John Ralston Saul and a delegation visited neighboring Kazakhstan and met with the President’s office there to present PEN’s concerns, especially for imprisoned writers Vladimir Kozlov and Aron Atabek. In Bishkek a delegation met with the President of Kyrgyzstan on PEN’s issues and with the federal Prosecutor on the case of Azinjon Askarov.

PEN held panels and discussions on LGBTQI rights, on surveillance, on criminal defamation, and on linguistitic rights. Resolutions on free expression and the cases of imprisoned and threatened writers were passed relating to Azerbaijan, China, Tibet, Cuba, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Honduras, Iran, Iraq, Kyrgyzstan, Mexico, North Korea, Russia, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine, and Vietnam.

PEN voted in four new centers—Liberia, Honduras, Wales, and an Eritrean center in exile, whose member reported on the many writers who are in prison and who have died there, bringing the total number of centers to 147 around the world.

In the capitol of Bishkek galloping horses are now replaced by ever present taxis—used cars from Europe and Japan with steering wheels on both the left and the right hand sides. Monuments and buildings from the Soviet era are strained with wear though guards still goose step around their peripheries. Members of Central Asian PEN welcomed the delegates with hospitality, with literature, with traditional songs and dance, with modern cinema about the past and with a hope of embracing broader freedoms in the future.

In Qatar, calls for release of prisoners come with the start of Ramadan

(This piece appears on GlobalPost.)

Commentary: The release of one imprisoned poet during Ramadan may seem a small act, but would be a significant humanitarian act toward a more enlightened state.

Muslim men perform the Eid Al-Fitr morning prayers outside the Ali Bin Ali mosque in Doha on September 30, 2008. Eid al-Fitr festivities marking the end of the Muslim holy fasting month of Ramadan are celebrated starting today in most of the Middle East countries. (KARIM JAAFAR/AFP/Getty Images)

I am not a Muslim, but I am focused on the arrival of Ramadan this year. The month-long observance began this weekend for 1.6 billion Muslims around the world. A time of fasting, increased prayer and charity, Ramadan is also a time when governments of Islamic countries grant amnesties to citizens and to those in prison.

Ramadan, the ninth month in the Islamic calendar, observes the time when Muhammad, a caravan trader wandering the desert near Mecca contemplating his faith, is said to have been called to receive the word of Allah. The revelation was eventually transcribed as the verses of the Qur’an.

The reconciliation of this holy time with political dispensations varies according to countries and their leaders. My focus is on the country of Qatar and the particular case of a poet in prison. Qatar has been in the news lately as the recipient of the five Guantanamo detainees. This transaction has taken the headlines.

But also in prison in Qatar is poet Mohammed Al Ajami, who has spent more than two years in solitary confinement for two poems. A father of four, Al Ajami is serving a 15-year sentence (reduced from life imprisonment) for poems criticizing the Emir and supporting the Arab Spring. One of the poems was read in a private reading in his apartment in Cairo, but was secretly taped by a fellow poet and uploaded on YouTube. Al Ajami was eventually charged a year and a half later with “encouraging an attempt to overthrow the existing regime.”

Al Ajami grew up as a friend in the household of the Emir’s grandfather, but he has refused to apologize for his poetry, and thus he continues to live behind bars. There is no legal recourse left to him. The only recourse is an amnesty or pardon by the current Emir. Should Al Ajami be released there are appointments he might have as a poet abroad.

The tradition of amnesties during Ramadan include last year’s release of 14 Nepalese in Qatar, three Britons jailed in Dubai, 65 prisoners in Gaza, , 82 Egyptians released in 2012 from Saudi Arabian jails. In a time when Qatar is facing criticism for its migrant domestic workers’ conditions, a time when Qatar is bidding for international conferences and facing controversy over its 2022 hosting of the World Cup, the release of one poet during Ramadan seems a small, but significant and humanitarian, act, an act which would evidence a more enlightened state to many who are looking for enlightenment in that region of the world.

Mohammed al-Ajami is an honorary member of PEN American Center. Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, a former reporter for the Christian Science Monitor, is a Vice President of PEN International and PEN American Center.

Qatar: A Poet in a Desert Cell

(This piece also appears on GlobalPost.)

DOHA, QATAR — We stood outside the guard house in the desert wind on the outskirts of the city. Doha Central Prison rose on the horizon of a barren, rock-strewn landscape, electric wires cutting across a cloudless sky. We had been told we had permission to visit Qatari poet Mohammed al-Ajami, whose 15-year sentence for two poems had been confirmed the previous day by the high court.

For five hours we stood, paced, sat in broken chairs, negotiating on mobile phones with the Attorney General’s office. The prison authorities had not received the request for our visit. The guards changed twice while we waited, guards from different nationalities as are most of the workers in Qatar. They were friendly, shared fresh oranges with us as the hours passed, but had no authority to help.

Inside the prison members of al-Ajami’s family were visiting him and knew we were out there. Al-Ajami knew we were there and wanted to see us. No one had gotten this far, the family later told us. But in the end we were denied.

For the last two years Mohammed al-Ajami has been in solitary confinement with limited access to visitors. A known poet in the Gulf and the father of four, al-Ajami was a literature student at Cairo University in 2010 when he recited a poem in his apartment among friends, a poem that allegedly criticized the Emir. The poem was in response to a poem by a fellow poet, but one of the students in the apartment recorded al-Ajami and uploaded the reading on YouTube. According to al-Ajami’s lawyer Dr. Najeeb al-Nauimi, a former Justice Minister in Qatar, the poem was spoken in a private setting and violated no law. Another of al-Ajami’s poems “Jasmine” was circulated on the internet and expressed support for the uprising in Tunisia and criticized all the Arab regimes.

Sixteen months later, al-Ajami was summoned in Doha and arrested, eventually charged with “encouraging an attempt to overthrow the existing regime,” “claiming that the Emir misused and not abided by the Qatar Constitution” and “criticizing the Crown Prince,” who has subsequently become the Emir. Al-Ajami was sentenced to life imprisonment after a trial held in secret where the Investigating Judge, a non-Qatari, was also the Chief Judge. [The Emir appoints all judges on recommendation from the Supreme Judicial Council, 75% of whom are foreign nationals, dependent on residency permits.] Later on appeal, Al-Ajami’s sentence was reduced to 15 years.

As representatives of PEN International and PEN American Center we—two American women—had come to Doha to argue for the release of Mohammed Al-Ajami, but by the time our planes landed, the court had already upheld the 15-year sentence. All judicial appeals were now exhausted.

A country of two million people, but with only 250,000 citizens, Qatar is one of the, if not the, richest nation per capita. During his reign the former Emir set a course of modernization and brought reform to the government, brought institutions of higher education to the kingdom and developed programs in the arts and set up a Center on Media Freedom. The West looks to Qatar as a leader in the region. The imprisonment of a poet on an offense of lese majeste has confounded many though in an interview, the Prime Solicitor General insisted the charges were not about freedom of speech but were brought because the poet publicly offended people and urged the overthrow of the government.

In Qatar itself the case has received little coverage. The news media is owned by the government and the Emir. Those familiar with the ways of the kingdom say the only recourse now for al-Ajami is a pardon by the Emir. However, if an apology is necessary for that pardon, a standoff may occur. According to al-Ajami’s lawyer, the poet has questioned why he should apologize for having spent the last two years in solitary confinement for sharing a poem in a private setting. His lawyer notes that Al-Ajami has had his career disrupted; he has missed seeing his family for two years, including missing the birth of his youngest child.

As I flew out of Qatar, I stared at the desert below now filled with sky scrapers and modern museums rising from the land. I considered the math. Over 90% of the jobs are occupied by men and women of other countries who have no rights of citizenship and can be deported. Only one in ten people are citizens; half of these are women, who have limited rights; over a quarter are children and the elderly. The country is run by a very small minority. I questioned whether the math was on the side of history.

Extensive gas reserves developed in the 1990’s have given Qatar its huge income and given the country a seat at the leadership tables of the region and the globe. But if the country puts its poets in prison, one must wonder. On the other hand, if the new Emir, just 33 years old, educated in Britain, pardons poet al-Ajami unconditionally as PEN urges, then perhaps the curve of history will extend outwards, at least for a while.

[Mohammed al-Aljami is an honorary member of PEN American Center. PEN’s representatives in Doha were Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Vice President of PEN International and Trustee of PEN American Center, and Sarah Hoffman, Freedom to Write Coordinator for PEN American Center.]

To sign a letter urging a pardon for Mohammed al-Ajami, click here.

The Last Colony?

The desert stretched out like a beige patterned quilt as far as the eye could see. The pattern looked like birds’ wings or boomerangs in the sand as the plane descended, then the swirls of sand resolved into rocky ground. In the distance a few concrete buildings rose around the pink watch tower of the airport as I landed in Laayoune in the Western Sahara.

A 103,000 sq mi stretch of desert and coastline twice the size of England, larger than all of Great Britain, the Western Sahara is called by some “the last colony.” Extending south between Morocco and Mauritania with almost 700 miles of coast edging the desert, the region has been in a political quagmire for the last four decades. Spain and Mauritania renounced their claim to the area in the late 1970’s, leaving only Morocco and the indigenous Sahrawi’s in dispute.

In February, 1976 the Sahrawis declared a sovereign state, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). For almost 16 years (1975-1991) Moroccan forces and the Sahrawi indigenous Polisario Front engaged in armed struggle. For the next 22 years the United Nations has overseen a political limbo. A referendum on independence was promised but has been stalled year after year.

I first became interested in the Western Sahara in the early 1990’s when chairing PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. The stories of torture and the conditions in the prisons of the Western Sahara were as grim as any I encountered. Many died and never made it out of the prisons, which were run by the Moroccan security forces. There were also bleak reports from prisons run by the Polisario rebels. I still remember stories of writers who took their bar of soap they were given each month and wrote poems on their trousers. The writers then memorized each other’s poems as a way of staying sane. They also scoured the prison yard in the one hour they were given each day and found scraps of paper and used coffee grounds to write their forbidden verses. Their stories demonstrated how one endured—through fellowship and a flight to the imagination.

Since that time the armed conflict has officially ceased; Morocco has granted amnesties, and most of the prisons have allegedly been closed, but there are still reports of “black jails” with grim conditions even in the capital. There are large areas where no one is allowed to visit.

My visit was brief, the visit of a tourist. I hired a taxi recommended by the small parador where I stayed, the hotel itself recommended by a friend of a friend who worked at the U.N. My driver spoke Spanish and Arabic, some French and little English. I speak English, some French, less Spanish and very limited Arabic, but we managed. I asked him to show me around the city then take me into the desert and then to the beach.

Those living in Laayoune are living their regular lives, women in long djellabas with head scarves, children going to school—you can hear their chatter and laughter on the streets—men also in djellabas or slacks selling in the shops and markets. But the area is a high security zone. The U.N. and the Moroccan security are present, and travel is restricted. No one is allowed too far east where a giant man-made sand berm separates the Moroccan-dominated region from the smaller Saharwi Polisario region near Algeria. Land mines are said to be scattered throughout the no man’s land in between.

In my 24 hours in the capital Laayoune, a city of around 200,000 with 70% of the Western Sahara’s population, I was stopped at six checkpoints. Two were on the way to the desert where a two-lane road stretched through the sand and rock. Any other journey in this area would need to be made with an off road vehicle or on a camel, but I saw only a few camels.

At one point on the way from the desert to the beach, I was delayed for 45 minutes with my passport examined twice. Everyone was friendly; I was friendly. A policeman with a moustache wearing a crisp blue uniform with white belt and military hat, looking very French (though the larger influence in the Western Sahara is Spanish), stood in the middle of the highway to stop us then came over to the taxi.

“Bonjour,” he smiled at me. “Bonjour,” I replied. “Passport?” he asked. I handed him my American passport. My driver had already called another policeman whom we waited for at a designated place in the city to get permission to go to the beach. At the beach are the fish processing plants and a phosphate plant as well as a promenade and beach and the Atlantic. We were given permission so I’m not sure why we are being stopped.

“Profession?” he asked. “Ecrivan,” I answered. “Journaliste?” he asked with suspicion. “No…ecrivan…romans.” I smiled. He smiled. He took my passport and went back to his car where he and the driver conferred for fifteen minutes. I watched them in the side mirror and wondered if I should get out of the car but decided I should stay inside. He returned to the car and gave me back my passport. He smiled I smiled. But still he didn’t let us go.

Meanwhile cars and a few trucks passed by without being stopped. They were driving south either towards the beach or all the way down the highway to Mauritania, over 600 miles away. I’ve been told this is a smugglers’ route. I wondered what traffic might have passed while I was being checked.

The driver returned and asked for my passport again. Another 15 minutes went by. I continued to watch them in the rearview mirror. Finally I got out of the car. I didn’t walk towards them. I just stood leaning against the taxi in the wind—a lone American woman traveling in the desert, sitting in the front seat of the taxi because it gave me a better view. I was probably not a sight they were used to. After almost 45 minutes, we were finally released. I don’t know what the conversations were. The driver told me it was about his license plate; one of its numbers was wrong; he was given a fine. Then why did they need my passport…twice, I asked. But he had no answer I could understand. Instead he took me to lunch at a restaurant on the beach, which I thought was either his father’s or his father worked at, then he invited me to his home, where he told me his mother had made me tea. His mother didn’t appear, but a tea service was set up, and he served me the delicious sweet mint tea in an elaborate Moroccan tea ceremony. When I paid him at the end of the day, I tipped him enough to pay the fine though I didn’t really know what happened, but we were smiling.

At the hotel, the U.N. representative who is a friend of a friend picked me up to go to the airport. Coincidently he was on the same flight back to Casablanca, where he would then head to the Azores. He was preparing for a meeting that would happen later in the fall. Fifteen refugees living on the Moroccan side of the sand berm will meet with refugees living on the Algerian side to discuss their lives. Observing them will be three Mauritanian anthropologists. The hope is that these meetings, which have occurred over the years, will help form bonds within the region. The larger hope for the region is that eventually real peace will break out. The topic to begin the discussion at the gathering will be: The Camel.

Parallel Universe in a Glassed Concert Hall in Iceland

If you want to understand politics—it’s like being in a book club where everyone discusses the grammar.

So said actor/comedian Jon Gnarr, Mayor of Reykjavik, Iceland when he addressed the recent 79th PEN International Congress. Gnarr was elected Mayor in 2010 from the Best Party, which he and friends with no background in politics created as a satirical party after the economic meltdown in Iceland a few years ago. They won over a third of the seats on the City Council with a platform that included free towels in all swimming pools, a polar bear for the zoo and “all kinds of things for weaklings.” After he was elected, Gnarr declared he wouldn’t form a coalition government with anyone who hadn’t watched the TV series The Wire.

The politician with a short black tie, a sense of humor and a view of politics as a parallel universe resonated with the audience of over 200 writers at the Opening Ceremonies of the PEN Congress. Writers from 70 centers of PEN gathered to deliberate and debate literature and the situation for writers and freedom of expression around the world, a world they agreed often bordered on the absurd, but the absurd with serious consequences.

The Assembly discussed and passed resolutions on the challenges to freedom of expression in countries including Mexico, China, Cuba, Vietnam, North Korea, Eritrea, Belarus, Syria, Egypt, Turkey, Tibet, and Russia. The delegates walked en masse to the Russian Embassy to present their resolution protesting the recent legislation on blasphemy and “gay propaganda.” And they applauded the announcement during the Congress of the release of Chinese poet Shi Tao 15 months before the end of his 10-year sentence.

“Shi Tao has been one of our main cases since his arrest in 2004, an honorary member of a dozen PEN centers and one of the first and most significant digital media cases,” said Marian Botsford Fraser, Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. “Shi Tao’s arrest and imprisonment, because of the actions of Yahoo China, signaled a decade ago the challenges to freedom of expression of internet surveillance and privacy that we are now dealing with.”

The delegates challenged the secret surveillance of citizens recently uncovered in the United States and the United Kingdom and the prosecution of those who revealed programs violating international human rights norms.

“As an organization dedicated to preserving free expression and creative freedom, PEN is particularly troubled by recent revelations concerning the nature and scope of electronic surveillance programmes in use by the United States’ National Security Agency and parallel programmes such as those being carried out by the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in the United Kingdom. As leaks about the U.S. government’s PRISM programme, the U.K. governments Tempora programme, and other such programmes make clear, certain governments now possess the capacity to monitor the private telephone, internet and other digital communications of every citizen on earth—among them, the communications of PEN’s 20,000 members worldwide.”

In this parallel universe one of the new centers PEN elected at the Congress was the PEN Center of Myanmar. PEN Myanmar will be an early citizens’ organization there defending writers and civil society in a country that just a few years ago was one of the most closed societies on earth. Also sitting in the glassed waterfront Concert Hall among the Assembly of Delegates were North Korean writers who now meet as an exile center of PEN, but as voices stir and comedians and actors and politicians mingle, who knows the universe that may yet emerge?

Two Voices Behind the Iron Doors

(In the past weeks I was brought to focus again on the situation of two writers in prison, one in China, the other in Turkey, both countries that have consistently challenged and imprisoned writers. In China the hope for expanded freedom of expression that came with the Olympics and China’s engagement with global institutions has not materialized, and Chinese writers remain in prison with long sentences. The situation in Turkey for a while was improving, but in the past year arrests have again escalated.)

Voice in China

I had dinner recently with three colleagues of Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel laureate and writer currently serving an 11-year sentence in a Chinese jail. Two of his friends, Shen Tong and the other friend arrived in the U.S. around the time of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, but the younger best-selling writer and democracy activist Yu Jie didn’t leave China until January, 2012 after being detained and tortured and put under house arrest. He now lives in Virginia.

Yu Jie consulted with Liu Xiaobo during the writing of Charter 08, the manifesto calling for democracy in China which resulted in the imprisonment of Dr. Liu. He and Liu Xiaobo also co founded the Independent Chinese PEN Center, and Yu Jie has written a biography of Liu Xiaobo.

At a round wooden table in a bustling Washington restaurant the friends outlined their campaign. Among their strategies, they are working to gather a million signatures worldwide calling for the release of Liu Xiaobo and his wife Liu Xia, who has been under house arrest since Liu’s imprisonment. So far they have gathered about half a million signatures in 130 countries, including from 135 Nobel Laureates. The Friends of Liu Xiaobo are also campaigning for the release of other prisoners of conscience in China. They and the Nobel Laureates are mobilizing support around the world and have been told the Chinese government has started to take notice and to worry about the scope of the campaign. Dr. Liu is the only Nobel Peace Prize Laureate in prison.

Here is the link to sign the petition.

* Friends of Liu Xiaobo Twitter: http://twitter.com/lxbfree,

* Facebook page: http://www.facebook.com/Free.Liu?fref=ts

Poem by Liu Xiaobo:

A Small Rat in Prison

a small rat passes through the iron bars

paces back and forth on the window ledge

the peeling walls are watching him

the blood-filled mosquitoes are watching him

he even draws the moon from the sky, silver

shadow casts down

beauty, as if in flight

a very gentryman the rat tonight

doesn’t eat nor drink nor grind his teeth

as he stares with his sly bright eyes

strolling in the moonlight

5. 26. 1999

Translated by Jeffrey Yang

Voice in Turkey

I reached into the drawer of my post box in Washington this week and pulled out a card addressed to Doame Leexa-Acker (the name no doubt a reflection of my poor penmanship on the receiving end.) The envelope was from Turkey, and the postcard inside had a picture of Diyarbakir, the ancient city in southeastern Turkey that is the capital of the Kurdish region and the hub of fighting for decades between the Army and the PKK.

In a neatly printed hand the card read:

21 March Newroz Kurdish religiots [sic[ celebrate.

1200 day not free. I’m healt [sic] bad.

I’m free about concerned. I need you children.

I at the house must be. I’ not killer!

I’m writer, lawyer, peacemaker.

I’ hope back you can be. Please.

Grand peace in the door.

Thank you for post cards 🙂

Best wishes,

Muharrem Erbey

Even with the challenge of English, the appeal resonated. I looked up his case and reminded myself of his situation: Muharrem Erbey is a writer and a human rights lawyer, Vice President of the Human Rights Association. He was imprisoned under the Anti-terror Law in 2009. According to PEN International, he has compiled reports on disappearances and extra-judicial killings in the Kurdish region and has represented individuals in the provincial, national and international courts, including the European Court of Human Rights. He was one of dozens of writers and journalists tried under the auspices of the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) trials which targeted pro-Kurdish writers, publishers, academics and translators, tried together as KCK’s “Press Wing.” He has published articles and co-edited a collection of Turkish and Kurdish language stories. His own short story collection, My Father, Aharon Usta was delayed for publication after his arrest.

Last fall Erbey wrote to those at PEN who had advocated on his behalf: “I send you my heart’s warmth from behind the iron doors and bars and damp, cold, wet walls of prison….My speeches and comments never contained words of violence.”

Circulating a writers’ work and giving voice to those silenced is part of what writers can do for each other. Below is a section of a translated letter from Erbey describing the seasons in prison with a link to the full letter:

I want to tell you how I have experienced the four seasons from behind bars.

Autumn. In the morning, as I reach over the barbed wire crowning this wall six or seven metres in height, the sun as it passes briefly through our ventilation system and away again, the sound of the sparrows that perch on the wire and fly off with the crumbs of bread we toss, the squawking of doves overhead, this sky stained a cold and faded blue, the wind that howls and carries dry fragments of grass through the ventilation – all work the ache of loneliness finely and deeply into me, as the captivity of my shivering body grows a storey higher. I am listening to the sound of the wind. The chattering of clothespegs hanging from the line, the clatter of water bottles roaming the area, flying newspaper scraps and silently wandering dreams, hopes that grow from a whisper to a roar – they strike the wall and go no further.

Winter. There is a weak sun that does not warm you. The air is cold. This place is alien to life, with its endless concrete and iron, these wire fences. The walls’ peeling grey paint, their damp, drains you of energy. Your dreams are caked in dust and soot. At 6 am, as we four men in each room wake to the metallic clank of iron doors, we wish that this were all a dream, but it is not; everything is real. As it happens, prison is the one place one would never want to be when waking. We have this privilege. The prison walls allow everything to pass, except time. I am freezing, my throat dries up, my eyes are burning, there is the weight of tonnes on top of me; it is as if I am tied in steel cord. I cough and I sneeze. In winter prison becomes a prison, and the cold season seems to go on forever. At night we go to the toilet dozens of times.

Spring. Taking root in a crack of broken concrete, seeds brought over the walls and wire by the wind display nature’s irresistible force with the unfurling of their leaves. At first glance you think that the seedling has broken its way out through the concrete. But nature stubbornly allows life to take hold, splitting concrete despite every restriction. An unimaginable aroma of oleaster surrounds us. You know that spring is here from the sound of birds and the smell of flowers. And from the flocks of birds in the sky, and its glittering blue.

Summer. The sun lays waste to it all, as walls and floor turn to a raging fire. I grow drowsy and still. As I shake my head before the spinning ventilator it rises above the walls and the wire fences and I fight to breathe, just as a fish in a tank rises to the surface and, looking desperately at the blue skies, gasps. At night the sound of a soldier whistling intermittently on the watchtower blends with an owl’s hooting. There is a wedding in the neighbouring village. The banging of drums, the women’s ululations and the barking of excited dogs plant a smile on my face just as soon as they steal in through an open window. How sweet to hear life even if we cannot see it!

If only prison did not teach one how beautiful life is. My sons Robin (10) and Robert (5) ask “Daddy, when will you be done here? How long until you come home?” I reply “Not long, not long.” In reality, I do not know when I will be done….

[Follow the links to send appeals on behalf of Liu Xiaobo and Muharrem Erbey.]

Rising Voices in Pakistan

I miss the sunrise in Islamabad. I have jet lag and sleep through it, but I am up by noon. A colleague, a respected researcher in the region, takes me to lunch in one of the remaining villages in the middle of the city, a city that was made from villages when it was constructed in the 1960’s. Islamabad is one of the most cosmopolitan cities in Pakistan, according to the guidebooks. We lunch in the hills under an awning on sofas looking out on other hills and restaurants attracting locals and tourists. We drink fresh squeezed orange juice—I drink the sweet, delicious orange juice at almost every meal—and eat a local chicken dish with nann piled high. In the evening I also dine outside by a fire with a journalist friend of a friend at an Italian restaurant in a residential neighborhood.

I am here for a conference of Pakistani and American journalists hosted by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) on whose board I serve. But this first day is my own and the only day I will not be inside the security corridor of the hotel or on a bus with an armed guard. Pakistan is reputed to be one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists and one in which Americans are urged to be cautious.

Pakistan stands at a pivotal point in its history right now with elections coming up in the next month for a democratic turnover of power. The expectation is that the civilian government will hand over to another civilian government peacefully for the first time in Pakistan’s history. Everyone I meet no matter their political affiliation is hopeful this election will occur.

“Even if imperfect, it is an important step in evolving democracy in the country,” says a leading human rights lawyer.

Central to the democracy the citizens aspire to is a free press. According to journalists at the conference:

–“What we do now in the media will make a difference 50 to 100 years from now.”

— “People are saying to the media: it is your job to protect us.”

–“Good journalists feel responsible and accountable to tell the story.”

The International Center for Journalists has sponsored and continues to sponsor over 150 Pakistani journalists to work in U.S. newsrooms around the country from California to Arizona to Texas to Minnesota to Rhode Island to Pennsylvania to Florida. It also sponsors 30 U.S. journalists to visit the Pakistani newsrooms. For most of the participants the visit is the first to each other’s country. The exchange has opened up perceptions and extended skill sets on all sides.

“Unless you touch the grass in each other’s yards, you won’t know each other,” said a journalist from Karachi who spent time working in Tucson.

In the U.S. the journalists work side by side on stories, including elections, schools, crime, the judiciary, local government, all the while learning about America and about techniques in American journalism. Americans also learn about Pakistan as the Pakistani journalists speak to Rotary clubs and schools and give interviews to the media.

Examples include:

–The journalist from Waziristan in the tribal territories in the mountains between Pakistan and Afghanistan who worked in Austin, TX blogging and is still blogging. “I loved Texas. The people cared for their families; they are like us.”

–The TV reporter based in Chicago who covered the US elections for his channel. As he stood in front of President Obama, he said he thought: “Here is a king of the world and yet he has a modest personality and is easily approachable.” The American experience was also good for him, he said, because he quit smoking. “After going to America, which has a no smoking culture, I cut my cigarettes down to 15 a day then to 5 a day then to none, and I now have quit.”

–The journalists in Pittsburg and in Charleston who hadn’t used social media except for family learned to use twitter and to tag and to send back notes on stories through smart phones.

–The Karachi journalist in Bakersfield, California who said he learned how American journalists fact checked content and shared information via facebook. He said he got tickets to see Conan O’Brien and Universal Studios for free and started a blog about his experiences and is still blogging.

–The journalist from Quetta who worked in Tallahassee, Florida and met the Mayor and Governor and Education Minister for the state. “I came back and did a story on education and mistakes in results in Punjab.”

–A journalist who was also a faculty member worked in Lancaster, Pennsylvania for a local TV channel and saw firsthand how important freedom was and saw the diversity of the culture, including the Amish country. “To understand the American ideal of freedom is so important for Pakistan. The journalist who picked me up every day told me democracy didn’t come easy; he said they had to struggle for it. It’s our way now. This is what I learned. American didn’t get it easy.”

–A journalist in Austin, TX had access to wander around with a camera. “I had a view of people and of the U.S. and that completely changed. They don’t hate Muslims or Pakistanis.”

–Another journalist was educated in school not to think well about America. “When I talk to different people and see the strong system and story of civilization and met Americans, I’m not against American people now.”

–One Pakistani journalist went with a Minneapolis journalist to interview the first Muslim elected to the U.S. Congress and was surprised how liberal he was in his views, especially towards gay marriage.

There were also journalists at the conference who’d been accepted to the program but were still awaiting visas, including a journalist from Waziristan and a woman television journalist in Lahore, who explained that in her city she couldn’t leave the house without covering her head; she longed to come to the US and study international relations.

Many of the American journalists went to Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad, but were not able to spend the same amount of time in the Pakistani newsrooms because of security concerns. They said they were surprised how much the Pakistanis wanted to engage with them. They too remarked on how alike they all were as they pursued their careers and families.

An editor in Florida told the story of a father of one of the women reporters working at his paper and living in his home. The father called him from Pakistan concerned about his daughter. The American editor shared his own experience as a father of a daughter, and the two families became friends.

Pakistan is acknowledged as one of the most dangerous countries for journalists. The danger to a free press isn’t the arrest and imprisonment of writers as it is in many countries. “The danger to the journalist used to be that he or she would be beaten up,” said one reporter. “In the old days you would get a good thrashing. Now they kill you!” Some cities like Karachi are more dangerous than others.

One leading journalist said there was no criticism of the Taliban in the press because it was too dangerous and because the Taliban are the biggest advertisers in certain media. “No story is worth dying for,” he said though others disagreed.

“To cover Pakistan is like looking through a fog,” said one American journalist based there who noted that people still remember the beheading of Daniel Pearl. “American journalists should be able to cover and go many places, but we can’t. Thirty-five journalists were assassinated in the past few years. If the media can’t work in certain areas, then how is it free?”

The constriction on the working U.S. and Pakistani media is balanced by the welcoming attitude of Pakistani civil society, noted one editor active in the Rotary Club back home where the visiting Pakistani journalists spoke. When he got off the plane in Islamabad, the President of the Rotary met him and took him around, and rotary members greeted him everywhere.

“When journalists on a major story are threatened and still run the story—that is courage,” he said. “Fight for a free press. The whole world is with you!”