Posts Tagged ‘Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression’

PEN Journey 20: Edinburgh—PEN on the Move, Changes Ahead

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest

I begin with the memories…

Castle Rock and Edinburgh Castle in Edinburgh, Scotland

—the imposing walls around Castle Rock which stands above the city of Edinburgh and dates back to the Iron Age,

—the 12th century castle/fortress inside,

—the Old Parliament building,

—the New Parliament building where we sat in high-backed theater-style seats in an arena,

—the dorm room residence inside Pollack Halls where we stayed at Edinburgh University near the city center, beside an extinct volcano,

—the receptions at Parliament House and Signet Library and the City Arts Center where there was never quite enough food for the overly hungry delegates who descended upon the platters,

—the UNESCO seminars on women and literature, including my paper The Power of Penelope,

—and elections, so many elections and speeches—three candidates for Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) Chair, seven candidates for International PEN President, nine Ad Hoc Committee members as precursors to a new governing board for International PEN.

These were the first contested elections I remembered in International PEN. A wider democracy was spreading with ballots and speeches. I also remember the tension and the occasional flares of anger, and the effort to hold us all together and ultimately the confident results and the determination to move forward in unity. International PEN President Ronald Harwood warned that while PEN badly needed to democratize “power” so it wasn’t too centralized, residing in the hands of a few, the delegates should not make the struggle personal and should go forward with a sense of humor. We were an organization of writers, not the government of the world, he admonished, warning members not to confuse bureaucracy with democracy.

—I remember the trip to Glasgow where a few of us had a stimulating visit and tea at the home of James Kelman (Booker Prize winner How Late It Was, How Late) who had been with us in the protests in Turkey a few months before (see PEN Journey 19) and the old Mercedes tucked in the garage in the working class neighborhood.

—And the Edinburgh International Festival, including the Edinburgh Book Festival, happening simultaneously all around us.

—And finally the exquisite August light in Scotland.

Program for 1997 PEN International Congress

I begin with memory then plunge into the minutes and documents of the 64th PEN Congress August, 1997 when delegates from 77 PEN centers around the world gathered. The Congress theme Identity and Diversity posed the questions:

In the contemporary world there are intense pressures, political or commercial, deliberate or unconscious, towards an imposed uniformity. One example is the effect on language. Indigenous languages, which embody particular traditions and experience, are in many countries under threat of displacement and extinction. These tendencies are inimical to literature which depends on its local personality for its color and effectiveness even when it achieves universal significance.

On the other hand, we live in an inter-dependent world where peace, prosperity and ultimately even survival, require co-operation. This international co-operation may be assisted by the use of a few languages which are widely understood. International exchange of the appropriate kind can also bring cultural enrichment.

How can these apparently contradictory objectives of diversity and co-operation be reconciled? Does literature have a role in this respect?

As with most abstract themes and questions, there is no simple answer, but the theme was a pivot, in this case both in the literary sessions and inadvertently in the business of PEN as the organization sought to restructure itself. Because this was my last congress as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee, the work of that Committee absorbed my focus. My two reports—one the official printed International PEN Writers in Prison Committee report and the other an address to the Congress—observed, and in a fashion related, to this theme:

[Written report:]

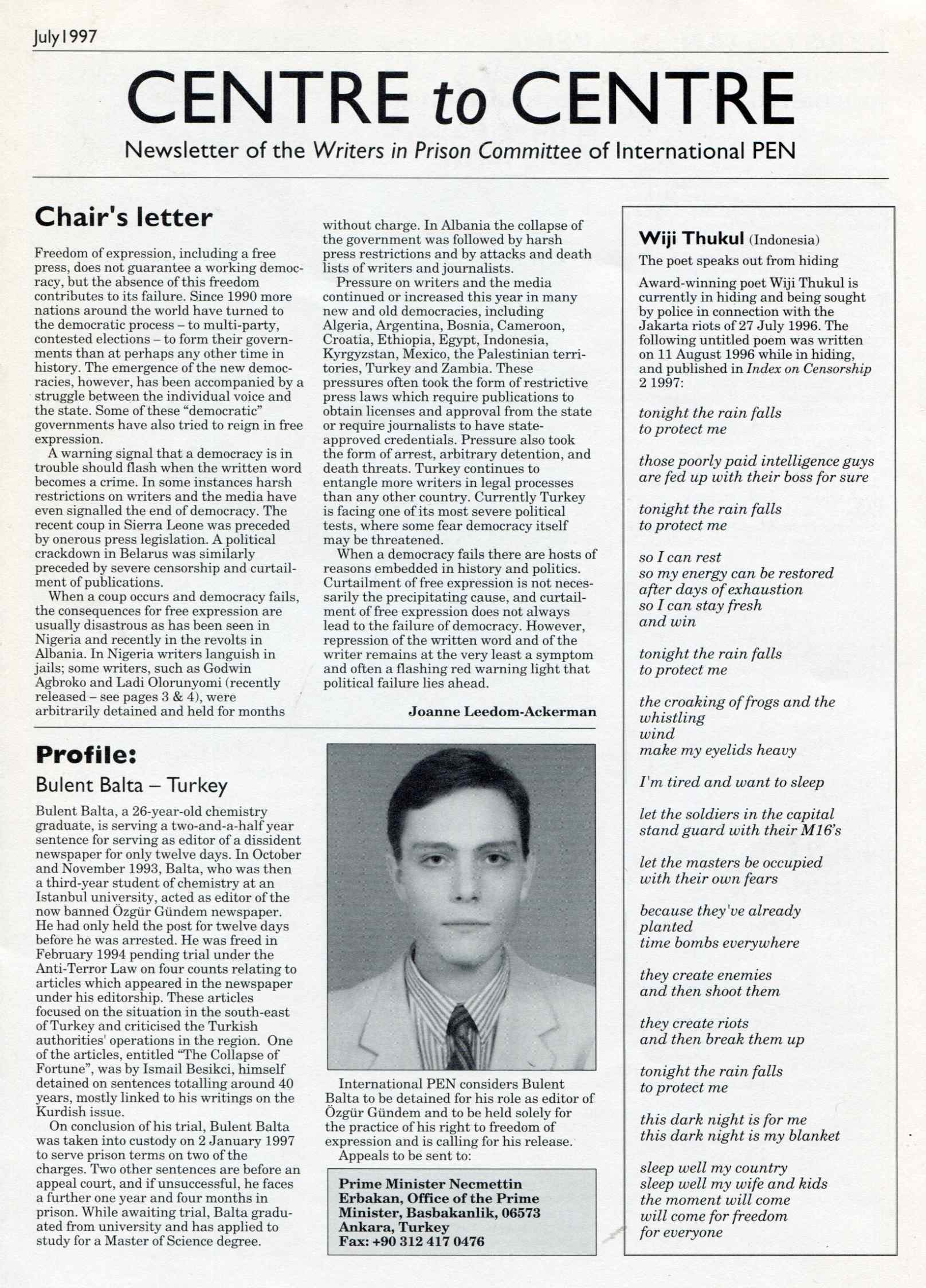

PEN Writers in Prison Committee Report, 1997

Tension between the individual and the state underlies the work of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. In some countries constitutions and governing principles are set out to protect the individual from the state, but in the majority of countries which PEN monitors where writers are imprisoned, threatened or killed, the state is organized to protect itself from the individual. Whether those countries be totalitarian regimes like China, Myanmar/Burma, Syria, Vietnam, Cuba or democracies like Turkey and South Korea, when the state holds itself superior to the rights of its individual citizens, freedom of expression is seen as a threat to stability rather than a sign of stability.

In 1997 the Writers in Prison Committee has defended individual writers in at least as many of the new and older democracies around the world as in totalitarian states. Since 1990 dozens of nations in Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Asia have restored or initiated multi-party democratic elections. The turn to the democratic process initially freed up restrictions on writers and journalists in many countries. However, after the first flush of these freedoms, after dozens of independent publications sprang up in Argentina, Belarus, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Russia, Sierra Leone, Zambia, etc., tensions mounted between the individual voice and the state. Restrictions and press laws followed, and writers once again found themselves facing prison terms on such charges as “insulting the President”, “writing derogatory statements against the government and government officials”, and “seditious libel.”

In some states like Sierra Leone harsh restrictions on the media preceded coups and the loss of democracy. Reporting restrictions and brief detentions of journalists enforced by the crumbling Mobutu government in Zaire (now Congo), did not serve to protect it from its eventual collapse. Earlier this year the political crackdown in Belarus was preceded by severe censorship and curtailment of publications. The collapse of the government in Albania was followed by severe restrictions on publications and attacks and death threats on journalists and writers.

When a coup occurs and democracy fails, the consequences for free expression are usually disastrous as has been seen in Nigeria where journalists continue to serve lengthy prison terms and are arbitrarily detained, sometimes for months without charge. Another instance of a threat to freedom of expression in Nigeria is that of PEN member and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka who is among 12 dissidents charged in Nigeria this year with the capital offense of treason. Soyinka remains free outside the country but is certain to be imprisoned if he returns.

Pressure on writers and the media continued or increased in many new and old democracies, including Algeria, Argentina, Bosnia, Cameroon, Croatia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Indonesia, Kyrgystan, Mexico, the Palestinian authority, Turkey, Uganda and Zambia. Pressures took the form of legislation which required publications to obtain government licenses and approval and/or required journalists to have state-approved credentials. Pressure also took the form of arrest, arbitrary detention and death threats…

When democracy fails, there are hosts of reasons embedded in history and politics. Curtailment of free expression is not necessarily the precipitating cause, and curtailment of free expression does not always lead to failure of democracy. However, repression of the written word and of the writer remains at the very least a symptom and often a warning light that political failure lies ahead…

The report goes on to outline situations of individuals under threat. Reading these reports is reading a political history of the time, told through the circumstances of individual writers. One of the highlighted cases at the Congress in 1997 was that of Iranian writer Faraj Sarkohi who’d signed a petition calling for freedom of expression, along with 134 other Iranian writers. Sarkohi had been kidnapped by the Iranian secret service while on his way to visit family in Germany; he was tortured and threatened with execution. Because of the worldwide protests by PEN and others, he was eventually released the following year and sent into exile.

Visiting the WiPC meeting in Edinburgh, Egyptian professor Nasr Hamed Abu-Zeid, a leading liberal theologian on Islam, told his story of being declared an apostate for his research and forced to divorce his wife, also an academic. They had fled Egypt where apostates could be killed. Şanar Yurdatapan, the Turkish activist who’d organized the Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression which many of us attended earlier that spring, had just been released from prison and also spoke to the meeting. The cases of Sarkohi and Abu-Zeid and Şanar were among 700 on the WiPC records.

[Address to Assembly of Delegates:]

After four years chairing International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, I’ve come to appreciate the simplicity of the Committee’s mandate and the complexity of its execution. To defend the individual’s right to free expression is to defend not only the essence of literature but also a cornerstone of free society. Our defense begins with the individual writer, but inevitably we are caught in the movements of politics and history where individuals struggle to shape, divert or oppose the tides. One of the most significant developments in the past few years has been the expansion of multi-party democracies across the globe, a development that at first glance would signal progress for free expression. However, from our work we have seen that democracy takes more than a polling booth and a list of candidates on a ballot to come to fulfillment. Freedom of the written word is essential for a democracy to work over the long term, and attacks on this freedom usually foreshadow larger repression and even the failure of the democracy itself.

This year PEN has seen repressive laws enacted and/or writers arrested and killed in the new and old democracies of Albania, Algeria, Argentina, Belarus, Bosnia, Cambodia, Cameroon, Croatia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Mexico, Russia, Palestinian territory, Peru, Sierra Leone, South Korea, Turkey, Zambia. Many governments have passed or tried to pass laws to bring publications under their control through licensing and government-approved credentials. These laws have been followed by the arrest of writers.

Repression remains the most severe in totalitarian states such as China, Cuba, Iran, Myanmar (Burma), Nigeria, Syria, Vietnam. China continues to imprison more writers for longer periods of time—over 70 individuals, many serving 10-20 years—than any other country. Many of the writers who were imprisoned during Tiananmen Square have been released in the past two years, but others have taken their place. The Writers in Prison Committee is watching with great concern legislation which could lead to restrictions on writers in Hong Kong as China takes over. The Committee is also following closely the continued repression in Myanmar (Burma) where prison conditions remain harsh and at least 25 writers remain behind bars, many with sentences exceeding ten years…

Many of the cases in Africa this year came from new democracies struggling with issues of free expression, including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Zambia. The military dictatorship of Sani Abacha in Nigeria continued to occupy the focus of many PEN centres who worked on behalf of writers still in prison. Protests from a number of PEN centres assisted in the release of two Nigerian writers…Our Committee heard a statement from PEN main case Koigi wa Wamwere from Kenya, where riots have broken out after calls for democratic reform. Centres around the world have lobbied for his release, and he is now out on medical bail, and the Writers in Prison Committee has assisted his return to Norway where he is living. He sent a message thanking PEN for its work on his behalf. He writes, “When dictators arrest writers, they guard them with more guns and soldiers than they guard enemy armies in captivity. Dictators fear ideas and writers more than they fear guerrilla armies. Afterall they know that without ideas even guerrilla armies would wither away and die…”

In Latin America PEN continued to protest this year the imprisonment and detention of writers in Cuba. This spring the Writers in Prison Committee issued its report on its Cuba trip last fall, focusing on dissident writers who often had to choose between prison and exile…In Peru, though legislative and judicial reforms have occurred in the last years, at least 11 writers there have reported threats and/or attacks from both governmental and non-governmental sources, and sixty writers and journalists have reported death threats or attacks in Argentina…

The Writers in Prison Committee continues to work closely with freedom of expression organizations around the world, sharing our research and disseminating via the internet so that when a writer is arrested as far away as Tonga, the King of Tonga suddenly found himself receiving faxes from all over the world.

Over the years the political tides have shifted, but members’ work on behalf of individuals and the friendship of writer to writer remain even after the writers are released. This year we saw releases in Cameroon, China, Cote d’Ivoire, Cuba, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Kuwait, Maldives, Myanmar (Burma), Nigeria, Peru, and Russia. On occasions we have gotten to meet and know the individuals personally. This year when the Nigerian government picked up Ladi Olorunyomi, the Writers in Prison Committee was quickly alerted. A number of us had had the opportunity to meet with her husband Dapo, a prominent editor and dissident now living in exile in the United States. Isabelle Stockton, our Africa researcher and I spoke in the morning, and she called him to gather more details. When I phoned him later in the day, he said, “I was going to call you, but before I could, PEN was already calling me.” As soon as we determined that Ladi Olorunyomi had not been charged with a crime, had no access to lawyers and was not allowed to see her family, we put out a Rapid Action to our centres and shared the information with other freedom of expression organizations all around the globe. During her almost two months in captivity we were able to monitor the case, share information, and hear with great relief when this writer and mother was finally released.

Dapo, who had secretly fled Nigeria a year earlier lest he be imprisoned, wrote PEN, “Thank you for everything! I am very grateful, but I lack the words, appropriate enough to convey my gratitude…to our good friends at PEN International.”

The business of PEN throughout the year and at the annual Congress also included the work of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, Women’s Committee, Peace Committee, the growing activity of the Exile Network and the literary sessions. The UNESCO seminars on Women’s Cultural Identity linked to the seminars on Literature and Democracy at the Guadalajara Congress the year before. In many parts of the world women still did not have full democratic rights. Significantly, in Latin America only 10% of books published were by women, and in Africa it was as few as 2%. But I must leave others to elaborate these activities.

At the 64th Congress results of the many elections yielded the next group of leaders who would take the organization into the last years of the 20th Century and into the transformation of governance. At the Congress Ronald Harwood was elected a Vice President as I had been at the previous Congress and as such we stayed connected and in the wings for the changes ahead.

Election results of the 64th PEN Congress:

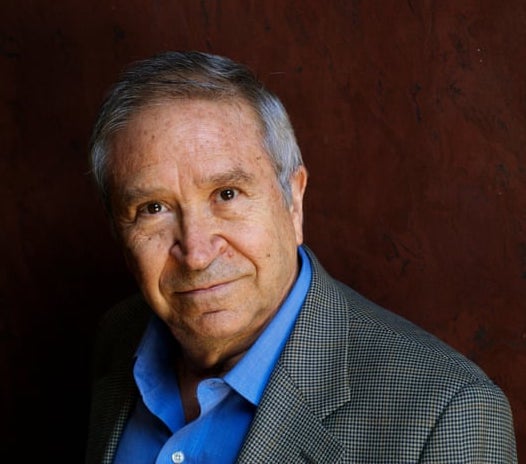

Homero Aridjis

Seven candidates stood for the presidency from Europe, Africa and the Americas though one dropped out. Homero Aridjis of Mexico, well-known poet, journalist and diplomat, was elected the next President of International PEN.

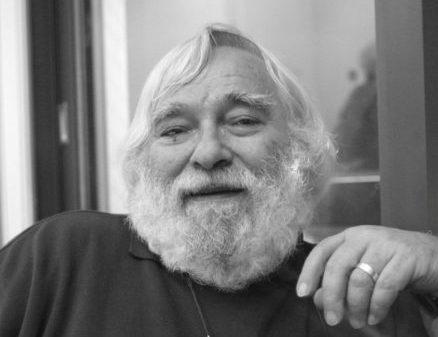

Moris Farhi

Novelist Moris Farhi, former chair of English PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, was elected chair of the WiPC. The two runner-ups Louise Gareau-Des Bois (Quebec PEN) and Marian Botsford Fraser (PEN Canada) agreed to serve for a year as Vice Chairs. In 2009 Marian Botsford Fraser was elected chair of WiPC and served till 2015.

The new Ad Hoc Committee elected at the Congress included Marian Botsford Fraser (Canada), Takashi Moriyama (Japan), Boris Novak (Slovenia), Carles Torner (Catalonia), Jacob Gammelgaard (Denmark), Vincent Magombe (Africa Writers Abroad), Gloria Guardia (Colombia), Gordon McLauchlan (New Zealand) and Monika van Paemel (Belgium). This committee was charged with considering all the restructuring proposals and preparing a draft for discussion and adoption by the Assembly of /Delegates at the 1998 Helsinki Congress. The Ad Hoc Committee was also tasked as a Nominating Committee to search for a new International Secretary. Alexander Blokh, re-elected for another year as International Secretary, planned to step down at the 1998 Helsinki Congress. Little did I know nor aspire to take on that role six years later.

New PEN Centers voted in at the Edinburgh Congress included Cuban Writers in Exile, Somali-speaking Center, Sardinian PEN Center, and a reconstituted Mexican PEN Center.

PEN International’s Writer in Prison Centre to Centre newsletter, July, 1997

Next Installment: PEN Journey 21: Helsinki–PEN Reshapes Itself

PEN Journey 19: Prison, Police and Courts in Turkey: Initiative For Freedom of Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

We sat on the ferry drinking strong Turkish coffee then handing over the emptied cups to a woman who read fortunes from the pattern of the leftover coffee grounds. As we huddled in the wind off the Sea of Marmara en route to the prison in Bursa, we speculated who among the passengers was following us. We were assured we were being followed.

Program for Initiative for Freedom of Expression Gathering, March 1997

I came to Turkey in March 1997 as the returning Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WIPC) (PEN Journey 18). I was heading a delegation of 20 PEN members from 12 countries. We’d arrived to support Turkish PEN, the Turkish Writers’ Syndicate, the Literary Writers Association and the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in the first Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression. We had signed on as “publishers” to an abridged version of the book Freedom of Expression. The original book included essays by those who were in prison or facing charges for their writing, particularly former president of Turkish PEN, the prominent novelist Yaşar Kemal. He was tried for an article he’d published in the German magazine Der Spiegel. (PEN Journey 17). Headlined “Campaign of lies,” the article called out the government for its human rights abuses, particularly its treatment of the Kurds.

Arthur Miller letter to Yaşar Kemal, March 1997

Bearing a letter from Arthur Miller, who knew Kemal and had himself come to Turkey with Harold Pinter in solidarity a dozen years before, I was among the 141 “foreign publishers” of the booklet Mini Freedom of Expression. This book contained a paragraph from each article published in the larger book. We joined the 1080 Turkish “editors” of the larger volume who included writers, theater actors, politicians, painters, cinema actors and directors, cartoonists, musicians, trade unionists, academics, lawyers, architects and others. The Turkish Penal Code made it a crime to re-publish an article that had been defined as a “crime” so that the publisher as well as the writer was charged.

The “publishers” had presented themselves before the State Security Court and faced charges of “seditious criminal activity.” After questioning the first 99 people, the prosecutor demanded the accused be tried under Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law and Article 312 on “disseminating separatist propaganda.” After six months only 185 of these individuals had been questioned and brought to trial. If these individuals were given the usual 20-month jail sentence, that would mean ten popular television programs would have to be canceled because their stars or directors would be in prison; five series would have to find new stars and change their story lines. The media would lose over 30 well-known journalists; 15 popular columns would be left blank. Eight professorial chairs would be left vacant, and universities would require new teaching staff. Theater stages and film sets would require many other artists, directors, musicians, etc., and 20 new books about prison life would be added to literature if every author wrote.

Turkey already had over 200 writers either in prison or entangled in legal processes, more than any other country. This protest initiative was unique and creative. The challenge to the court was to bring charges against so many. The State Prosecutor had dropped charges against the foreign participants on the grounds that he wasn’t able to bring us to Istanbul for questioning though the Turkish citizens who had prepared and distributed the booklet could be tried. The organizer of the initiative Şanar Yurdatapan suggested we come to Istanbul and challenge the prosecutor. Though PEN members were willing to come to support their Turkish colleagues, no one wanted to end up in a Turkish prison.

“No one will go to prison,” Şanar assured. The prosecutor had to act within six months, and even in the unlikely event charges were brought, we’d go home before a trial, and there was no extradition from the US, UK and many other countries because no such “offense” existed under their laws. Unlike organizations such as Greenpeace, PEN was not a direct action organization. PEN dealt in words, protest letters, diplomacy, meetings, on occasion candlelight vigils outside embassies and stories in the media. But Şanar, who was a song writer, civic activist, not a PEN member, instinctively understood the dynamics of nonviolent direct action and understood how to get attention and make the point that the Turkish laws were unjust and unfairly administered.

On our first day, which was Women’s Day, we joined the Saturday Mothers’ rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members. The gathering had been held every Saturday for a year and a half at Galatasaray Square, ten minutes from our small hotel in Taksim. The crowd of mothers and children held pictures and signs of their loved ones, mostly Kurds, who had been taken away, assumedly by the government and likely killed. On the edges of the crowd police in riot gear gathered but didn’t interfere. Meeting at Galatasaray Square is now banned for Saturday Mothers by the Ministry of Interior since August 25, 2018. They still keep the rally at Human Rights Association branch in one of the back streets.

Saturday Mother’s Rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members.

From there a number of us went to a women’s rally where hundreds of Kurdish women in traditional dress marched with banners shouting, “We are mothers; we are for peace! Mafia is in Parliament; students are in prison.” Along the route men cheered and dozens of police lined the road frisking and checking bags. This was the last weekend of a 40-day protest all over Turkey. At 9pm every night people around the country turned out their lights or blinked their lights and shouted out their windows and in the street, “Go Away!” in protest over the government. The idea was that people would have one minute of darkness to get years of light. At dinner that Saturday evening we watched as the streets filled with shouting and the lights in restaurant blinked on and off.

Women’s Day march of Kurdish women with police positioned along the route.

The trip to Istanbul was my first of what would turn out to be dozens of visits to Turkey over the years for PEN, for other organizations, and for family. In 1997 the times were tense; soldiers with their weapons and machine guns were stationed at the airport; armed police were on the streets; we were followed; the phones at the hotel were likely tapped. It was difficult to imagine then that it would get much better in the following decade as it did and then much worse in recent years. I’m not sure today we could hold such a gathering with confidence.

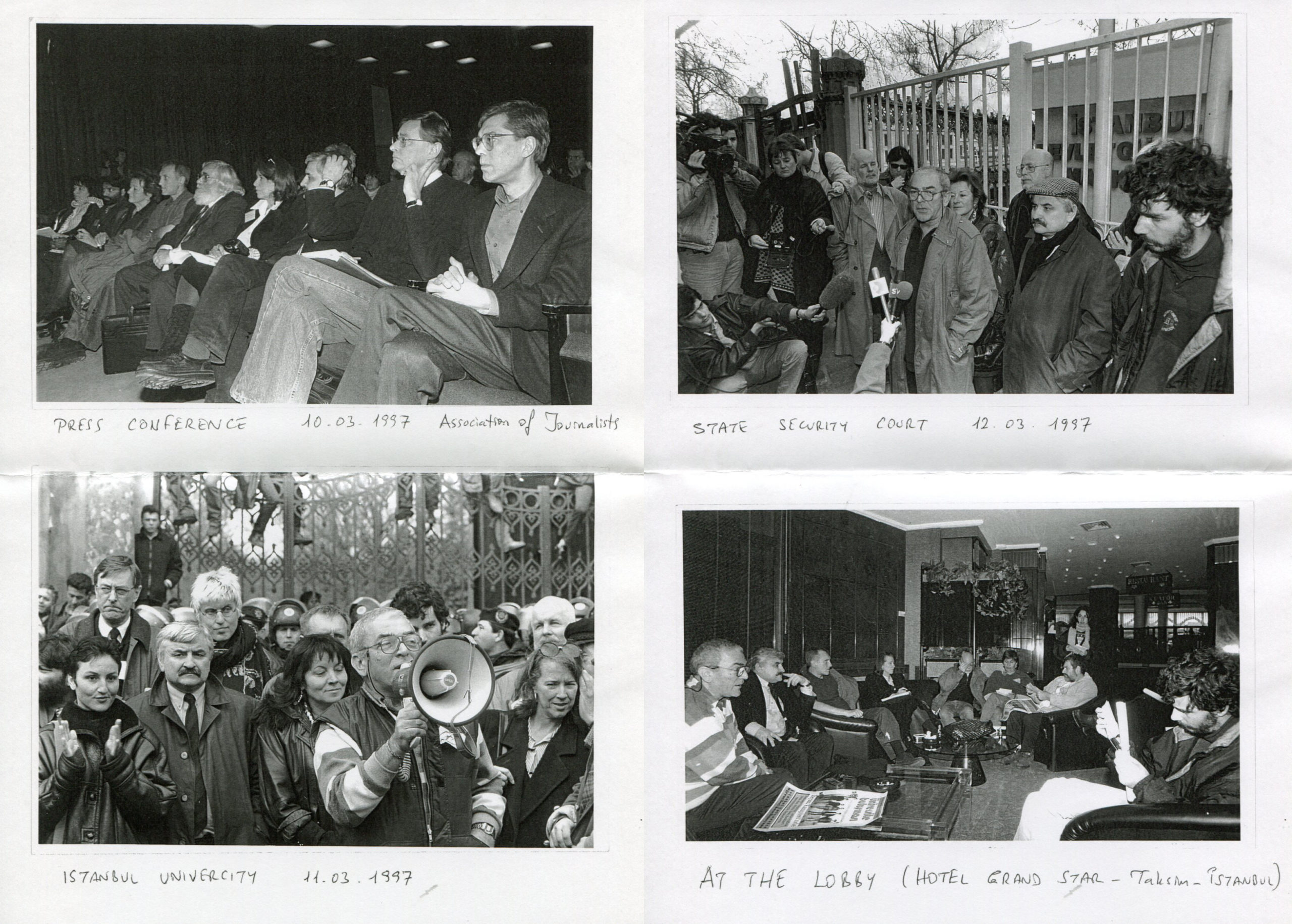

Throughout our visit we were covered by the press, including two visits to the State Security Court. In 1997 the legal way to meet publicly was to hold a press conference so we spent our days in press conferences, including one at the Journalists Association. Because I was Chair of the WiPC, I was often the one explaining why we were there. I emphasized that we had come out of respect for Turkish literature and writers. We had not come to break Turkish laws; we did not consider editing a book a crime. We were there to uphold the international covenants that Turkey had signed, approved and became a party to: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 19), Article 19 of the UN Convention on Civil and Political Rights and Article 90 in the European Convention on Human Rights. We noted that Article 90 in Turkey’s own Constitution declared that no law should supersede these international covenants.

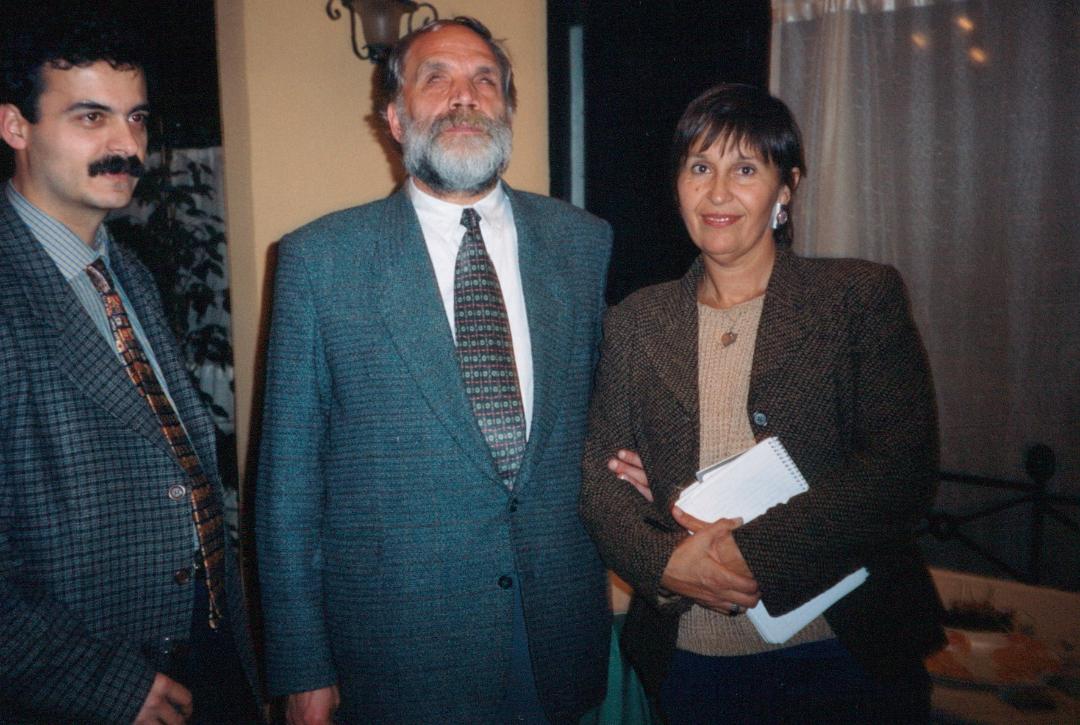

Our PEN delegation included representatives from Canada (Quebec), Finland, Germany, Holland, Israel, Mexico, Palestine, Russia, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States and Turkey. The delegates included James Kelman, Booker Prize winner from Scotland and Turkish writers including Yaşar Kemal, Orhan Pamuk and others.

PEN members from 12 countries join Turkish colleagues for dinner at the first Gathering of the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in Istanbul, March 1997

On Monday we started the day at the State Security Court where Şanar petitioned the prosecutor for an appointment to question one delegate who had to leave early. Because the prosecutor didn’t want to bring charges against “international editors”, an act that would bring international attention, the “Turkish editors” could use this failure as further evidence of the unfair nature and application of the law when they took the case to the World Court. We approached the State Security Court again on Wednesday, when the prosecutor actually locked the gates and wouldn’t see any representative of our group. In the end nine of us—from USA, England, Scotland, Finland, Holland, Sweden, Canada (Quebec), Mexico and Russia—signed a form which said, “I accepted to be one of the collective publishers of this book willingly and I am aware of the legal responsibility. I have nothing else to say.” These forms were then sent registered mail to the prosecutor.

Two small groups visited prisons and the prisoners of conscience, including Dr. İsmail Beşikçi and his publisher Ünsal Öztürk in Bursa and journalist Işık Yurtçu in Adapazarı prison. Louise Gareau-Des Bois from Quebec PEN went to the Adapazari prison and was able to visit with Işık Yurtçu.

Kalevi Haikara from Finland and I went with Şanar on the ferry to the prison in Bursa where we met Ünsal Öztürk’s wife Süreyya. We waited and waited and talked together in the bleak courtyard with grey concrete walls rising around us topped with barbed wire, with guard towers looming over us. We went to the pink concrete building of Bursa Prison with a shield on the door “Ministry of Justice Bursa Special Prison” and waited there too. But we were not allowed to see İsmail Beşikçi, the noted Turkish sociologist and philosopher who wrote about the Kurds history and living conditions. He was one of the few non-Kurdish writers in Turkey speaking out about the treatment of the Kurds. At the time he was also one of the longest serving prisoners. He’d been sentenced to over 100 years though he was released from jail two years after our visit. Of his 36 books, 32 were banned in Turkey.

Kalevi Haikara from Finish PEN and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, WiPC Chair and member American PEN outside prison in Bursa, along with Süreyya, wife of prisoner Ünsal Öztürk (middle picture) and in conversation at Bursa Prison (far right picture.)

We were also not allowed to see Ünsal Öztürk, Beşikçi’s publisher, who had completed more than a three-year sentence. We met with the press which had gathered. We paid the outstanding fine against Öztürk with funds raised from Turkish writers, artists and many of the visiting PEN members. Öztürk was released the following day though there remained 30 outstanding cases against him, 62 charges waiting to be brought to court, all relating to Beşikçi. Every time he published a book, a charge was brought, but he kept publishing. Öztürk and his wife joined the conference.

The following day we attended the Justice House hearing of the “Kafka Trial.” When one editor of the Freedom of Expression book—actor Mahir Günşiray—faced the judges, he’d read a paragraph from Kafka’s The Trial. The paragraph offended the judges, and they brought a civil suit against him. Sixty-five other writers and artists signed on and said they also endorsed the reading of Kafka and should thus be guilty too. We all piled into the small room where the defendant Mahir Günşiray and his lawyer and the judge met. The hearing was the second or third for him, but with the room full of observers, the judge again postponed the proceedings.

At hearing of “Kafka Trial” in the Justice House

Many of us went next to Istanbul University to participate in a Forum on Freedom of Expression. However when we arrived, hundreds of students were protesting in the plaza, surrounded by riot police with shields. The situation was tense. In Ankara students had recently been arrested after they’d unfurled a banner in Parliament challenging the 300% tuition increase at state universities. The student protesters there were tried with the demand of 18-year prison sentences. The students at Istanbul University asked if we would speak at the rally. None of us were prepared for this potentially explosive scene. The writers who’d come to speak on freedom of expression asked me to talk for the group, all except Sascha from Russian PEN who also wanted to speak. Sascha, Şanar and I addressed the crowd. I emphasized that we were there to uphold the right for free expression, not to take a side with any particular party of government or to take sides on how education was financed in Turkey, but to insist that individuals should have the right to discuss, debate and write about these issues without facing prison terms. We urged that the protest stay nonviolent. We were then ushered out through the police corridor.

Rally at Istanbul University (Includes Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN), James Kelman (Scottish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Kalevi Haikara (Finish PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (WiPC Chair/American PEN), Hanan Awwad (Palestinian PEN), Turkish writer Vedat Türkali, and Şanar Yurdatapan (with bullhorn).

In the evening the Istanbul Bar Association hosted us. The head of the Bar noted that the Turkish Constitution protects the state against the individual rather than the other way around as in the US. Everyone agreed there was free expression in many quarters of Turkey, but that the danger arose when one addressed Kurdish issues and Kurdish separatism and referred to the PKK.

Attending the meeting was the former PEN main case Eşber Yağmurdereli, a blind poet/dramatist, who’d served 14 years in prison. Released August 1991, he’d spoken in September 1991 at a meeting on behalf of Kurdish prisoners and had new charges brought against him. After five years he was still awaiting the resolution of that case. His passport had been taken from him. He could be sent back to prison for more than 20 years. He said he was unable to write, and if he wrote, he had to hide the writing and not publish. He earned his living now as a lawyer.

Meeting with Istanbul Bar Association. Eşber Yağmurdereli (middle) and Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN) on right.

I also met the young brother of Bülent Balta, an investigation case. Balta, a chemistry honors graduate, a Turk, not a Kurd, had agreed to edit Özgür Gündem, the Kurdish newspaper, because of his sympathies for the difficulty of the Kurds. He had no particular experience as an editor, and after only 11 days was arrested and was serving a four-year prison sentence.

That evening the protest at Istanbul University was all over the news, including pictures of me with a bull horn speaking, but my words had been translated into Turkish so I had no clear idea what it was reported I was saying.

Early the next morning I slipped out of our hotel and walked to a large international hotel nearby where I called home. I asked my husband to confirm my return flight the following day. He asked what the flight was, but I told him to check with the travel agent and confirm. Over the phone I didn’t want to give flight details. I told him what was happening, including the widespread coverage of the protest with my participation, and he told me a colleague in Washington said that the American Embassy knew I was there and warned me not to leave the hotel. I had to leave the hotel, I explained. I was leading the delegation and events were planned, including a farewell dinner on the Bosphorus.

At the final panel/press conference, I noted that I had two sons, and as I observed the young people here, especially the young police officers and the young students, I felt sorrow that these youth were set across battle lines from each other. There was so much talent and promise we had seen. For the first time in the three days of speeches and press conferences, emotion stirred in my voice and I paused for a moment. One of the headlines the following day read something to the effect: “She Cries for Turkey!”

Panel at Initiative for Freedom of Expression Conference, Istanbul March, 1997

The following morning I was to be driven to the airport, but the driver didn’t show up, and I was left to find my own transportation in a taxi. The atmosphere around the conference had slowly made each of us cautious, even slightly paranoid. As I climbed into the taxi, driven by a stranger, I remembered the fortune teller on the ferry a few days before. Proceed with caution…was that her warning? You will make friends…was that the prediction? The road ahead is fortuitous but also fraught? In fact, I no longer remembered what her fortunes were, and I didn’t believe in fortunes or scattered coffee grounds, but I left Istanbul with a strong belief in the people and a commitment to the country and to the writers and publishers and lawyers and journalists and to the young people I had met and to the promise they represented.

In years following I returned to Turkey on numerous missions for PEN and for meetings with Human Rights Watch, with the International Crisis Group, on a trip with UNHCR looking at the Syrian refugee crisis, and several trips with my oldest son who wrestled in the World Championships and European Championships in Ankara and in the World Championships again in Istanbul and also lectured in mathematics at Koc University and other universities and with my youngest son who lived in Istanbul for two years with his two young children and wrote as a journalist on the Turkish/Syrian border and has set two of his four published novels in Turkey.

PEN International Writers in Prison Committee Centre to Centre newsletter special Turkey section April 1997

Next Installment: PEN Journey 20: Edinburgh—PEN on the Move, Changes Ahead

Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression

(Below is my talk for the Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression, a conference held every two years, but this year it is being held via video May 26-27. For the first time in 21 years the organizers judged that a gathering in person was too problematic given the arrests and crackdowns on the media. Turkish presidential elections are scheduled for June 24 alongside parliamentary elections.)

I first visited Turkey for the inaugural “Gathering in Istanbul” in March, 1997. At the time I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee and joined 21 other writers from around the world. Along with over a thousand Turkish artists and writers, most of us had signed on to be “publishers” for Freedom of Thought, a book that re-issued writings which had violated Turkey’s laws against “insulting the State.” The book included work by noted authors, including celebrated novelist Yasar Kemal. None of us aspired to go to Turkish prison, but we understood the importance of showing up and showing solidarity with our Turkish colleagues. During that Gathering we visited prisons where writers and publishers were incarcerated and visited court rooms where they were charged.

Inaugural “Gathering in Istanbul” March 1997

In the subsequent decade, conditions for writers in Turkey improved. An amnesty released writers from prison; oppressive legislation was rescinded though new laws replaced old articles in the penal code. But the climate opened. We all took hope that Turkey might signal an opening of consciousness and an easing of political and legal constraints globally.

Unfortunately, that opening has closed, and we are here today on video because the biennial ‘Gathering in Istanbul’ for the first time in 21 years is too problematic to hold in Istanbul. The situation for freedom of expression is worse than ever in Turkey with more writers in prison than anywhere else in the world. Depending on the statistics of the day, there are more than 250 journalists and media workers in or facing prison terms, 200 media outlets closed, and thousands of academics and civil servants let go or facing charges.

Yet we are here, even if on video. And the organizers remain steadfast in Turkey. I take heart in the commitment of individuals who understand that freedom of expression is central to a free society and work towards that end.

For this “Gathering in Istanbul” it was suggested we look at “Freedom of Expression Around the World,” not just in Turkey. My general observation is that the world is reversing direction from those days 20 years ago when many thought authoritarianism was yielding globally to democracy and freedom.

The situation in my own country, the United States., is as fraught as it has ever been in my lifetime in the relationship between the government and the media, but the press is protected by the U.S. Constitution, laws, history and society. The majority of U.S. citizens still remain committed to protect freedom of expression and to remain vigilant though sometimes I fear we are preoccupied with our own challenges to the exclusion of more dire challenges to free expression around the world. I also fear we have lost credibility and impact when speaking out on these issues. Yet as an American, I can hold vigils in front of prisons, sit in courtrooms, write articles and books, meet Ministers, and then return home. I’m able to write and to speak out without being threatened with imprisonment or death.

I’d like to focus the rest of my talk on the courageous writers in the Democracy Movement in China, especially after the death of Liu Xiaobo, Nobel Peace laureate who died last July in prison after serving nine years of an eleven-year sentence for “inciting subversion of state power” because of his participation in the drafting and circulating of Charter 08. I have the privilege of being an editor for the English-language edition of The Memorial Collection of Liu Xiaobo. The collection includes writings from dozens of Liu’s colleagues inside and outside China, who knew him and pay tribute to the man, his ideas and to the consequential voice he had in articulating and taking action on behalf of a free society.

One of the authors of Charter ’08, a document signed by hundreds of Chinese writers, intellectuals and citizens, Liu Xiaobo and others set out a democratic vision and path for China, using rule of law and consensus, not weapons and violence. It is individuals like Liu Xiaobo and his fellow Chinese writers and thinkers, who one hopes will eventually prevail. Like the writers and thinkers in Turkey, they are committed to ideas, to the rule of just laws and to nonviolent means to bring about change and wrest society from tyrannical modes.

Liu Xiaobo understood that a free society begins with the individual consciousness. In his Final Statement “I Have No Enemies” he addressed the court:

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people. It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to progress of our country to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

Such sentiment was difficult for many to accept, especially after he died. Many questioned whether he would have expressed the same sentiments had he known his end. I’ve been assured by those who knew him well that he would have stood by this statement. His commitment was rooted in his view of himself and of what it would take to change society.

A longtime colleague Cui Weiping has observed that Liu Xiaobo “…viewed the world through boundaries of his own making. Whatever he wouldn’t allow into his life, he was also unwilling to allow into the world. For instance, if he didn’t have violent tendencies in his own life, he would not let the behavior of others impose on him. If he valued freedom and autonomy, he would not become mired in hatred because of the crimes of others, since hateful people were dominated by the other side. If he experienced the good things and positive feelings of human life, he knew all the more that he must allow what was good and open to take root in himself and not what was biased and narrow-minded. His life was oriented toward love and light, not toward hatred and darkness. This was his own decision and what he was willing to take upon himself; every person writes his own history. Other people could choose to go along with Xiaobo or advance alongside of him, but there was no need to feel that this was his error or flaw that must be corrected or surmounted. Twenty years passed like a day, and he was a trailblazer for people who insisted on their own ideas. China lacks trailblazers like Xiaobo, and that is what allowed him to become a standard-bearer for the Chinese Democracy Movement and gain the widespread endorsement of the international community.”

A small number of Chinese writers drafted Charter 08, thousands of citizens have signed it, but only one went to prison and died.

No one knows and few can predict the success of Charter 08’s vision and the ultimate impact of Liu Xiaobo, but history has a long arc and may well bend to those who see our common humanity and the universal value of freedom for the individual. By focusing on the individual’s responsibility for his own behavior and consciousness, Liu offered the tools to empower all, for no government has the mandate over one’s individual consciousness. There the individual sets his or her own terms of engagement with the world.

In reading the essays of the many Chinese writers who knew and admired Liu Xiaobo and his vision, I also think of Turkish writers and artists I have had the privilege to know over the years who continue to work towards a free society.

The two countries and circumstances are different, and many would say Turkey is not as extreme as China, but in all the years I have been working with PEN, it was Turkey and China which placed the most writers under pressure. In China the sentences were often longer and harsher, but the numbers were greater in Turkey. But in both nations the individual voices of writers, publishers and artists continue to inspire.