Posts Tagged ‘Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’

Spring and Release

I saw the first daffodils today…and forsythia…and the buds on cherry blossom trees. Spring with its regalia is starting to blossom, at least here in Washington, DC.

In the freedom of expression community renewal is heralded this week by the release of writers from prison in a number of countries, including Qatar, China and Azerbaijan. While the writers were unjustly imprisoned in the first place and many hundreds still languish in jails because they have offended governing powers, the releases of Qatar poet Mohammed al-Ajami after almost five years in prison and Chinese writers Rao Wenwei and Wang Xiaolu and half a dozen writers in Azerbaijan are cause for quiet celebration.

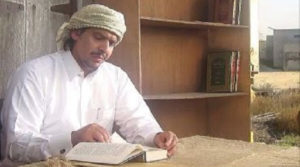

Qatar: In the fall of 2013 another PEN colleague and I stood outside the sprawling prison in the desert around Doha where Mohammed Ibn al-Dheeb al-Ajami was held in solitary confinement. After meetings with Justice Ministry officials, we’d understood we would be allowed into the prison for a visit. However, after five hours waiting in the desert wind, we were denied access. Al-Ajami’s family, who were visiting inside, told us later that Al-Ajami knew we were there and took some heart in that. Al-Ajami was imprisoned for “insulting the Emir” in two poems which he read at a private apartment in Cairo but which were surreptitiously recorded and posted by a student on YouTube. One of the poems “Tunisian Jasmine” expressed support for the uprising in Tunisia that launched the Arab Spring and challenged rulers throughout the region. Al-Ajami, who is the father of four, was originally sentenced to life in prison, reduced to 15 years.

PEN centers around the world, including American, Austrian, English and German PEN worked on his behalf as did Amnesty, Human Rights Watch and other organizations championing freedom of expression. Many voices protested, many hands tried to push open the prison door. Just last week at a Washington dinner I noted Al-Ajami’s imprisonment to an individual headed to Qatar for high level meetings. Those who deal with Qatar are always surprised that this Emirate which boasts education and partnerships with Western universities would imprison a poet for his poems. It is not a comfortable outcome that it is a pardon and not an apology by the Emir which brought about Al-Ajami’s release, but it is still cause to be glad.

China: There are more than 40 writers in prison in China, including Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo. Recently two—Rao Wenwei and Wang Xiaolu—were released early. Rao Wenwei is a writer charged with “inciting subversion of the state power” for articles published on the internet. His 12-year sentence was cut short by four years with his release. Wang Xiaolu was arrested for a story on the stock market crash on suspicion of “fabricating and disseminating false information on the trading of securities and futures.” Through the efforts of PEN centers, particularly the Independent Chinese PEN Center, the cases and situation of writers in prison in China stay at the forefront of protests.

Azerbaijan: Half a dozen writers are being released in Azerbaijan this month. The Baku Court of Appeals is expected to release journalist Rauf Mirkadirov today, according to Sports for Rights coalition which includes PEN, commuting his six-year prison sentence to a five-year suspended sentence. President Aliyev has signed a pardon decree that includes 14 political prisoners, including the writers Parviz Hashimli (journalist), Abdul Abilov (blogger), Hilal Mammadov (journalist), Omar Mamedov (blogger) and Tofiq Yaqublu (journalist). The European Court of Human Rights also issued a judgment in Rasul Jafarov’s case finding violations of Rasul’s rights to liberty and security. Rasul is expected to be released shortly. Dozens of political prisoners, however, remain in Azerbaijani jails, including journalists Khadija Ismayilova and Seymur Hezi.

(*For background on any of these cases or the many remaining political prisoners in Azerbaijan, here’s the full list with case details: http://www.helpsetthemfree.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/The-list-of-Political-Prisoners-in-Azerbaijan_December-2015.pdf)

Overheard in Washington: Presidents and the Movies

I’m sitting in one of my writing haunts in the morning when a man sits down nearby. He’s joined by a woman. They are waiting for others. Slowly the team begins to gather who have managed to get into DC in spite of the snow and ice storm yesterday. One has come all the way from Scotland. Several are in from New York.

As usual I’m working by the window, barely listening to the conversation ten feet away, except as it grows more interesting. Two more join, now four, now six, now seven people have congregated, one with a bag of inexpensive thank you gifts (“under $25”) for those who’ve helped arrange a visit to the White House. One begins to show the others the views of the White House where filming can take place. The Hay Adams Hotel overlooks Lafayette Park and the White House. The W Hotel overlooks Treasury and is also near the White House. The team hovers around the computer and plans where “our motorcade” will drive and where shots of the White House and other Washington landmarks can be taken.

Last year around this time, I was sitting in this same spot and overheard the beginnings of a campaign for the far-off presidential primaries. (see April, 2015 post) It was discouraging then to realize we were only at the beginning of a year-and-a-half campaign for the White House. Now here we are—the primaries have begun and the campaign I overheard is in full, if precarious swing.

Today I listen to a movie being planned. I wonder which movie. In a way I envy having a whole team on a story as I sit alone writing. The team has their scripts in hand and folds them as they prepare to brave the rain outside which is washing away the snow. Scripts tucked in pockets, backpacks hoisted on backs, bags gathered, the crew sets out.

We still have another nine long campaigning months before the U.S. Presidential elections. This film will take at least as long. Already wearied by the incessant arguing and calumny of the campaign season, I find I anticipate with more enthusiasm Hollywood’s fiction. I don’t know how the President will fare in the film. No doubt there will be intrigue, a discernible villain and let us hope a worthy protagonist.

View on the Bosphorus: Rights in Retreat

I’m sitting on the Bosphorus today in Istanbul looking across to the Asian side over the balustrade of a European porch. I’ve been visiting Istanbul over the last 20 years for conferences, recently for visits to refugee camps and most often now to see family living here. Istanbul is one of my favorite cities, full of heart, multiple cultures, history and citizens of intellect and warmth.

But recently the atmosphere has chilled. I’ve come on this trip to participate in the launch of Human Rights Watch’s 2016 World Report which focuses on the “Politics of Fear and the Crushing of Civil Society” as causes that imperil citizens’ rights around the world. Istanbul was chosen as the launch city because it sits at the nexus of east and west, is the crossing point for millions of refugees fleeing the Syrian war and has an active civil society and free press that are now severely tested as the environment for rights deteriorates.

“Government-led restrictions on media freedom and freedom of expression in Turkey in 2015 went hand-in-hand with efforts to discredit the political opposition and prevent scrutiny of government policies in the run-up to the two general elections,” according to Human Rights Watch (HRW) 2016 World Report.

The restrictions include the investigation of Cumhuriyet newspaper for posting a report showing weapons on trucks allegedly headed to Syria. The paper’s editor Can Dϋndar and Ankara representative Erdem Gϋl were arrested and are now in jail awaiting trial. Other journalists have been arrested for criticizing the government. There have been police raids on media groups, a widespread firing of journalists perceived to be in opposition to the government, in particular to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Publisher Cevheri Gϋven of Nokta news magazine and editor Murat Çapan spent two months in jail for “inciting an armed insurrection against the government” for a report and a satirical picture of Erdoğan. Nokta’s website remains blocked by a court order. Months of pretrial detention have been handed out to those allegedly insulting Erdoğan via social media and during demonstrations.

I first came to Istanbul in spring, 1997 for the “Initiative for Freedom of Expression”, a conference that brought together PEN International and freedom of expression organizations in Europe to protest the harsh treatment of writers by the Turkish government and courts. Charges had been brought against the celebrated Turkish novelist Yaşar Kemal for an article he wrote for the German magazine Der Spiegel in which he accused the Turkish army of destroying Kurdish villages. Though he was acquitted, he is quoted as saying, “One person’s acquittal does not mean freedom of expression has arrived. You can’t have spring with only one flower. We still have to work very hard to achieve democracy in Turkey. I will continue to write these things until there are no trials against expression.” Kemal passed away last spring at age 91.

At the time activist and song writer Şanar Yurdatapan organized a publication that included Kemal’s essay and the writings of other Turkish and Kurdish writers who had been banned or imprisoned. He mobilized Turkish artists and publishers and academics to sign on as the publisher, and he asked writers from the more than 100 centers of PEN International around the world also to sign on as publisher. The publication thus challenged the government which would have to bring charges against hundreds of people as publisher. And so the Gathering for Freedom of Expression was born.

I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee during that time, and along with dozens of writers from around the world, I arrived in Istanbul for the conference. Şanar and his colleagues organized visits to prisons to try to see the many writers and publishers incarcerated, visits to courthouses to observe hearings and trials, a visit to the prosecutor’s office to insist that we too should be charged as publisher. We understood the embarrassment such would cause the government, though none of us aspired to go to a Turkish prison. The Initiative for Freedom of Expression held multiple press conferences because the only legal way to gather at that time was to have a press conference. Yaşar Kemal spoke at one of these.

There was also a freedom of expression conference called at a university where hundreds of students had mobilized in the campus square when we arrived. Many were protesting tuition hikes, not writers in prison, but the two gatherings merged. Riot police surrounded us all as we addressed the crowds.

The period of 1997 in Turkey was charged. The heavy hand of the State was palpable. The police were at every gathering. Cars followed us. In 1997 PEN International recorded more writers in prison or tangled in the judicial processes in Turkey than almost anywhere in the world except perhaps China.

But citizens were mobilizing and claiming space for expression. In the subsequent years the Initiative for Freedom of Expression and other freedom of expression and human rights organizations recorded regularly the abuses and circulated these and mobilized actions. Şanar was sent to prison because of his work and there studied the history and principles of civilian based resistance, practices he had instinctively employed. Every other year the Gathering for Freedom of Expression assembled in Istanbul, several of which I attended. Turkey could mark its progress by the decrease of the numbers of writers and publishers in prison. Until last year.

At the launch of HRW’s World Report this week, Şanar and I met again, smiling to see each other but not smiling about the state of affairs. Turkey appears to be reverting back to the ways and days of the 1990’s. Şanar has returned to song writing, still passionate, but addressing issues through music and advising (not quite on the sidelines) the next generation of activists.

Refugees: The Great Walk Now or Never

The black rubber dinghy had just landed on Mytileni’s rocky beach on the Isle of Lesvos, Greece. The 41 people crammed precariously on the raft quickly dropped their orange life jackets and looked around to make sure their friends and relatives had also made it to land.

A father knelt before his curly headed son, around 3 years old, took off his life jacket, checked his clothing—damp, but not too wet—and tried to explain where they were. The boy smiled, looked about and then spent his time trying to get his heel back into one of his wet sneakers. I was able to help him as his father looked for his wife, who’d made it to land further down the beach. The family had left Aleppo a week ago, waited three days on the Turkish coast near Izmir for transport and now, finally had safely reached the shores of Europe.

From here they would continue their long journey to a new life, which they hoped would be in Germany. Before them lay at least half a dozen train and bus rides and walks with their two backpacks containing all their belongings. Also ahead were multiple registration centers in each country they would pass through.

Along with the 760,000 people who have come through Greece since April, they were embarking on “The Great Walk,” or some call the trek “The Great Wait.” With winter coming and borders closing, it is a “now-or-never” journey as Europe absorbs the largest migration since World War II. Almost half—45%—come through Lesvos, 58% men, 16% women, 26% children, according to statistics from the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR).

As Syrians, they are lucky, if having to flee one’s home destroyed in war can be considered luck. Most Syrian refugees—96-98%—will eventually find new residencies. Syrians comprise 45% of this great exodus. Another third are Afghan, a tenth are Iraqi. The rest are Eritrean, Central African Republic, Iranian, Somalians, Moroccan, Algerians and others, according to figures from UNHCR. The latter four nationalities have slim chances to resettle in Europe.

In the past month access for “direct arrivals” has closed. Only refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan are allowed the onward journey into Europe. These nationalities comprise 85% of those on the move. The rest are turned back. The European Union has also agreed to accept 160,000 in a formal resettlement process, which takes one to two months and requires refugees to accept whatever country they are assigned. Again, only certain nationalities are included in this relocation process—Syrians, Iraqis, Eritreans, those from the Central African Republic and perhaps soon Afghans, according to Alessandra Morelli, UNHCR Senior Operations Coordinator in Greece.

“History is passing in front of our eyes,” Ms. Morelli says at the UNHCR office in Athens. “I feel responsible that we build a Europe that is open and not one of walls.”

In the Lesvos registration site Kara Tepe I met with a group of 21 family and friends who’d arrived earlier in the day. They had come through Lebanon from their village and were part of a small Shia sect of the Alawites. The Assad forces had insisted the men must join the Army at the same time ISIS had come to the village and kidnapped three girls and killed many people and threatened that if the men didn’t join them and convert, they would be killed.

They fled the village, leaving behind a 65-year old father, a lawyer who’d been imprisoned and tortured and didn’t want to leave. Another woman through tears said her 19-year old son was still in Turkey trying to raise money to cross. She would stay on Lesvos until he joined her. Among their group were infants and toddlers, who were now running in and out of the small Ikea houses assigned to the families until they moved on later in the day or the next day.

“I fled not as a deserter, but because I didn’t want to fight,” said one of the fathers. “It was impossible to live in Syria any longer with our family. We needed $12/day to live and could only make $2. I was working in a restaurant; my wife studied French in university and couldn’t find a job. For the last three years there have been no jobs. There was constant shelling. Our children were afraid. There was no future for them, and we are watched on all sides. Planes are constantly flying over; the children aren’t sleeping; shooting is everywhere. When it’s dark, no one goes out.

“But despite all the difficulties we still face, we feel safe now,” he added. “We’ve received good treatment here, enough to feel like human beings again. I want my children to be raised in Europe out of all the bad complexities in my part of the world.”

Harsh stories abound for each refugee, but there are also stories of hope and of an outpouring of good will along the way. Volunteers from Greece and all over Europe have come to assist. There are Doctors Without Borders treating the sick, Clowns Without Borders entertaining the children; there are Families Like Ours from Portugal providing tons of clothes, Green Helmets from Germany putting in wooden floors in the tents, Samaritans are winterizing the shelters with tarps. There is a local Greek mother who donated a stroller and wrote a letter to the mother who would receive it. There are Spanish Life Guards who wait on the beaches in wet suits, ready to go out into the ocean to help those trying to get to shore.

There are local and international nongovernmental organizations—Save the Children, Action Aid, Habitat for Humanity, International Rescue Committee, Red Cross, etc., all taking up specific roles in this migration. There are agencies of the European Union, providing security and registration.

Since early fall the United Nations High Commission on Refugees has been on the ground helping coordinate all these processes. The priorities for the refugees are employment and education for their children.

Their journeys, with variations, look like this: They arrive from Syria into one of the bordering countries—Iraq, Jordon, Lebanon or Turkey. There they likely find a smuggler, pay the fee, wait on the border for their turn, sometimes a wait of several days. From Turkey, they climb on a raft, often at night so they are less likely to be seen, and they take the 4-6 mile trip of 2-4 hours, depending on conditions. Shipwrecks and drowning are real dangers and have taken the lives of hundreds, six Afghans just in the time I was there.

On the beach they are met by volunteers and usually by representatives of the EU or UNHCR and the Greek municipality, who take them to a first staging area, where they are given food, water, the opportunity to shower, charge their phones, and change into dry clothes if needed. They are then put on a bus and taken to the registration centers, where their papers are checked; they are finger printed; their nationalities are sorted out; they are given official registration documents and advised on possible next steps. This process can take 2-8 hours. They have the option of staying the night in a tent or small Ikea house for families.

From the registration center they continue to Athens on a ferry. This they must pay for. Their registration and documents are again checked, and they board buses to Idomeni in Northern Greece near the Macedonian border, where, if they are Syrian, Iraqi or Afghan, they are allowed to cross. They walk from the border to a registration site, enter a large tent with wooden benches and wait to be called to register again, this time for Macedonian papers. After registration, they are given food and water, clothes if they need. At all the centers there are safe places and play spaces for women and children, run by Save the Children and other organizations. Over the loud speaker the announcement of all the services available are repeated in English and Arabic, including: “You don’t need to pay for anything.” Everything at the site is free. They wait in tents or in small Ikea houses or outside if the sun is shining for the train to arrive. The train was late the day we were there, and it is not free. It will eventually take them to Serbia, where they must walk to the registration center and again register for new documents. From there they will get trains or buses to their next destinations with walking in between, making their journey northward to Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, Austria and for many on to Germany or Sweden or other countries.

War is at their back. Their future is focused on their children. Their destinations are partly places of imagination, where they imagine jobs and schools and safety. But the triage is intensifying. Winter is coming. The European Union is paying Turkey three billion Euros to secure its borders and service the three million refugees already in Turkey so that they stay. Quotas are filling rapidly in countries like Germany and Sweden, where refugees perceive opportunities. Through facebook and through families who have gone before them, and from the media, Germany and Sweden and Holland and a few other countries have become their mecca, and countries like Portugal, which is open to refugees, have so far received few.

“They are families like us. We want to help,” said Barbara Guevana at the Macedonian border camp. She is one of the founders of Familias Como as Nossas—Families Like Us—a group of women who didn’t know each other but connected through facebook to assist Syrians with housing, education and transportation to Portugal, which has allotted 4500 spaces for refugees. Seventeen women drove three days to Croatia to meet Syrian families, taking with them clothes and food and assuring them Portugal was waiting to welcome them.

“But people don’t know about Portugal,” said Ms. Guevana. “In Arabic the name means ‘Orange,’ and they question why they should go to ‘Orange.’ We assure them we want them to come. The Portuguese government is willing to fly them to Portugal if they get to Austria.”

This migration is changing the face of Europe and challenging the future of the European Union. “We need to manage borders, not close them,” insists Philippe Leclerc, the new UNHCR representative, who has just arrived to head the Greek operation.

While Germans, French and Austrians were at first welcoming, Eastern European nations like Poland, Hungary, Slovakia have been more resistant. And everyone agrees that the November terrorist attacks in Paris have changed attitudes.

“We need to realize these people are fleeing the terrorists; they are not the terrorists,” said Maureen White, board member of the International Rescue Committee and director of Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies Center on Migration and a fellow traveler on this trip.

As the sun sets, we drive from Macedonia through the official checkpoint, showing our passports at each border as we return to Thessalonica. When we cross into Greece, we find our car behind a caravan of busses filled with refugees and migrants who are being returned to Athens. Today was a major police action that cleared the area called “the Green Field” where those not allowed to cross had started camping and piling up. These are not Syrians, Iraqis or Afghans, but all the other nationalities who hoped to pass into Europe. Nineteen hundred people in 49 buses will be put up for the night in the old Olympic facilities in Athens and in the morning told their options, including applying for asylum in Greece, an unlikely outcome, applying for resettlement, an option at the moment only for Syrian, Iraqi, Eritrean and Central Africans or returning to their countries of origin.

Democracy in Africa: Who Can Chat with Kabila?

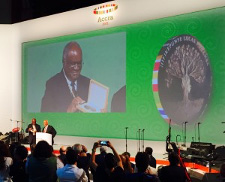

I returned last week from two conferences and a debate back to back in Africa. The Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which has developed an index on good governance and transparency in Africa, gave its annual prize to a former African leader, followed by a day-long discussion on “African Urban Dynamics.”

The Africa Report Debates inaugurated its series with the question: “Democracy vs. Development.”

And the International Crisis Group, an organization dedicated to analyzing and offering policy recommendations for current and potential conflicts worldwide, (and on whose board I serve) gathered its Africa program for an internal analysis.

From the gatherings of eminent African leaders, policy makers, scholars and commentators I took away the following contradictions across the continent:

–There is an expanding and active civil society at the same time there are spreading and virulent extremists and criminal networks.

–There are growing numbers of working democracies at the same time entrenched leaders are trying to change constitutions to hold onto power in single-party states.

–There is developing urbanization offering services and employment for citizens while slums and marginalized communities expand.

The debate “Democracy vs. Development” concluded overwhelmingly that the two must go hand in hand.

“Fast and equitable development and diversity come through democracy,” according to Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Ethiopia. But he added, “Democracy is a process. It matures over time and grows from the inside. It can’t be prescribed. It needs institutions and education. We don’t need paternalistic intervention.”

Ethiopia was pointed to throughout as making significant economic progress. But in a break between panels, I asked Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus about the restrictions on freedom of expression in Ethiopia and the number of writers and journalists now in prison there. His answer: “They broke the law.” Their imprisonments have been challenged by major freedom of expression organizations like PEN International, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty, Committee to Protect Journalists, as well as by African PEN centers, I pointed out; this is not a positive sign for healthy government. He and I did not resolve the question between us.

Good news and reasons for hope on the continent include the peaceful elections and transfer of power this year in Nigeria, which has a strong and vocal civil society even as it struggles with the radical extremism of Boko Haram in the North and with criminal trafficking. Also positive is the immanent transfer of power through elections in Burkina Faso, where citizens rose up peacefully last year and opposed the extended 27-year rule of its leader, demonstrating a strengthening civil society. Ghana, where the conferences convened, held peaceful Parliamentary elections while we were there.

“We need heroes,” said Mo Ibrahim, who initiated the conference and the award which was given to the former President of Namibia. Hifikepunye Pohamba won the $5 million prize for “forging national cohesion and reconciliation at a key stage of Namibia’s consolidation of democracy and social and economic development.”

“We must reject the manipulation of the Constitutions,” said former President Pohamba in his acceptance speech. “No individual or group of people should be allowed to abuse power from democratically elected leaders with impunity.”

Electoral transitions in East, West and Southern Africa could unhinge or advance their regions, including in Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Cameroon, Uganda and Zimbabwe. In many of these countries, the current presidents are hoping to hold onto power past constitutional limits which they are trying to alter or past public tolerance. Outcomes of these elections will be important indicators to watch.

Informal conversation outside the symposiums:

“Who can chat with Kabila?” (President of DRC). “I understand he’s scared. His father was killed here.”

“Who can offer him immunity?”

“Can he have a soft exit?”

“Will he exit?”

“I don’t think so.”

Behind all the statistics and the headlines, the story after all is always about people.

Life instead of Death…Rationality instead of Ignorance

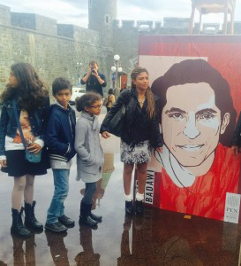

Of all the lively discussions, the literary evenings, multiple resolutions generated at PEN International’s 81st Congress last week in Quebec City, the image that stays in my mind is of the petite wife and children of Saudi blogger and editor Raif Badawi standing in a puddle on the plaza by his picture in the early morning, along with delegates from PEN centers around the world.

His wife and children now live in Quebec, which has also offered Raif Badawi a home, but he remains in a Saudi prison with a ten-year sentence and 950 more lashes of punishment, then a decade long ban on travel, all for setting up a digital forum to encourage social and political debate within Saudi Arabia. He has been found guilty of “insulting Islam” and “founding a liberal website.”

The PEN Congress, which hosted writers from 84 centers in 73 countries, featured three writers with “empty chairs,” including Raif Badawi, Eritrean poet, critic and editor Amanuel Asrat and murdered Honduran journalist Juan Carlos Argenal Medina. PEN called for the release of Badawi and Asrat and justice for Medina. It also targeted the cases of writers imprisoned, threatened, killed or at risk in Bangladesh, China, Cuba, Eritrea, Honduras, India, Iran, Mexico, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Tibet, Turkey and Vietnam.

Badawi’s message via his wife to PEN members after receiving an earlier PEN Canada One Humanity Award was: “We want life for those who wish death to us, and we want rationality for those who want ignorance for us.”

Unity on the Potomac?

The Potomac is smooth as a mirror today. The wind occasionally dusts its surface. On lamp posts by the river, American flags catch a light breeze and flutter under an overcast sky. Fall is stirring in the air though joggers still run in shorts and tee shirts and students pace to the boathouse for afternoon rowing practice.

A mile form here Washington is recovering from two major State visits in four days—first Pope Francis and literally on his papal heels, Chinese President Xi Jinping.

But here on the river with a view of Memorial Bridge and the Kennedy Center, of the traffic cruising on Rock Creek Parkway and airplanes taking off from National airport, it is unusually quiet for a Friday afternoon. Couples stroll by. A mother with a pram stops and looks out on the gray-brown water. The city is perhaps letting out its collective breath. There have been no attacks, no disasters.

Washington has feted and listened—been told to unify for greatness by the Pope and then looked for common cause with the Chinese leader who has limited shared values and certainly not an agenda of individual freedom.

It is always an existential question whether America—“one nation under God with liberty and justice for all”—can live its ideals and live in the world.

From a political point of view, the right to dissent and the forums to express disunity are fundamental and the very evidence of a nation breathing, of a democracy working. No one is arrested or imprisoned for their disagreements. We have the freedom to be in gridlock though surely there is a better way to demonstrate freedom. The question ahead as political campaigns heat up is whether we can breathe and disagree and at the same time govern and guide.

The spiritual call for unity is one each citizen must find in his own sanctuary, not in the halls of Congress.

As I’m writing, I hear sirens whining in the distance growing louder and louder, and in front of me on this terrace overlooking the river, a great crane appears and a wall is literally lifted out of the walkway. I’m told these walls, which lay buried most of the time, were installed after the last great flood wiped out the waterfront. The waitress returns and tells me they are now raised on any threat of a flood. Down river floods have occurred and may be moving our way.

“What to Read Now: War Narratives”

From the September/October 2015 issue of World Literature Today

While the US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been going on for fourteen years, much of American literature from these conflicts is only now emerging. I appreciate the veterans who’ve woven the simultaneously “worst and best days of their lives” into literature. They have turned to all forms to find their truth—poetry, short stories, memoir and the novel. (Disclosure: I’m the mother of a Marine who served in both conflicts and is now one of the novelists listed here.)

I have framed these suggested readings with a history from the Great War a hundred years ago and with a diary of one of the long-serving detainees in Guantánamo. Truth in literature is determined in part by point of view. In these books, the reader can take a journey from many perspectives.

Margaret MacMillan

The War That Ended Peace

Random House

In this nonfiction book, Margaret MacMillan narrates history through the lives of those responsible for World War I. The characters and cousins could populate a fiction collection with their dramas, imaginations and absurdities. MacMillan offers an inside view, revealing the people and stories behind the politics and events that led to a war many feel—and felt at the time—shouldn’t have happened.

Brian Turner

My Life as a Foreign Country: A Memoir

W.W. Norton

The author writes of his deployment as an Army sergeant, beginning in the US learning to identify body parts, watching combat on television, and then arriving in Iraq and facing real combat in the first Stryker brigade. “We rode on a war elephant made of steel,” he writes of the nineteen-ton tank. A poet (Here, Bullet), Turner narrates his experiences and his return home in a poet’s language, which spins the harshest circumstances—the soggy, trodden straw—into gold and art.

Phil Klay

Redeployment

Penguin Press

A veteran of the US Marine Corps assembles a dozen short stories and first person narrators—soldiers on the front lines, in the rear, at desks, with their family, friends, wives and girlfriends back home. The narrators’ voices are witty, unflinching, nostalgic, and the stories make the reader laugh, cry and wonder how a generation honed on this conflict will return to life as it was.

Elliot Ackerman

Green on Blue

Scribner

This novel narrates the war in Afghanistan from the point of view of an Afghan orphan who gets caught up on the American side of the conflict in order to keep his brother alive. He quickly learns that the war has too many sides and so many points of view that truth shimmers only in the eyes of the beholder.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Larry Siems, ed.)

Guantánamo Diary

Little Brown

Guantánamo Diary tells the story of the “war on terror” from the point of view of one who has been detained, tortured, and continues to proclaim his innocence. With a literary and humane voice, Slahi, edited beautifully by Siems and redacted by a censor, renders the horror and humanity in this war that will not end.

EYES ON PLUTO… “WE DID IT!”

Headlines from earth yesterday heralded the Iranian Nuclear Deal, but some of us were looking skyward. On a small green campus tucked into suburban Maryland at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab scientists, engineers, media, friends, family, faculty and board of Johns Hopkins University awaited the report back from Pluto. The New Horizons spacecraft, built by Hopkins APL engineers and scientists, had arrived at the outer planet three billion miles away after a nine and a half year journey. That evening the spacecraft was reporting in after 22 hours of silence while it gathered extensive data as it passed within 7750 miles of Pluto.

The spacecraft, which had been built in a record four years at APL, had traveled at a rate of a million miles/day (between 31,000-46,000mph depending on its orbit). The evening before it had started downloading data and taking pictures in a rapid collection of scientific information. It couldn’t do that job and call home at the same time so its progenitors waited anxiously at Mission Control, aware that any number of unpredictable events like a pebble size bit of detritus colliding could disrupt and destroy the mission.

“Stand by for telemetry….” Mission Operations Manager (MOM) Alice Bowman alerted. At 8:52:37pm—right on time—New Horizons called home. “We’re in lock with telemetry with the spacecraft,” she affirmed as one by one the systems managers reported: “MOM, propulsion is nominal…MOM, thermal is nominal…MOM, power is nominal…” Nominal meant normal. MOM meant Alice. The conclusion: “We have a healthy spacecraft and we’re outbound for Pluto!” The room at Mission Control and in the auditorium nearby burst into cheers and tears and gave a standing ovation. It was a remarkable moment and extraordinary achievement.

This composite of enhanced color images of Pluto (lower right) and Charon (upper left), was taken by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft as it passed through the Pluto system on July 14, 2015.

The mission had proceeded like clockwork. It had been a team effort over a decade and a half, occupying 2500 people. The very best scientists and engineers built the space craft, designed its scientific mission (including the first student-designed project on a NASA mission), programmed its course. The trajectory included an important scientific data-gathering pass of Jupiter, where the spacecraft received a needed gravity assist which sent it hurling on its way into deep space.

New Horizons arrived at the closest approach to the planet just 72 seconds early. That precision over nine years and three billion miles was almost impossible to comprehend except to the scientists and engineers who understood that precision was essential to accomplish the task. Even a small margin of error projected over that amount of time and space could be disastrous.

The mission exemplified a remarkable achievement of teamwork and partnerships among NASA, universities, and the U.S. Department of Energy which supplied the plutonium power source. The nuclear power it provided will allow the spacecraft to operate until 2030. The total power draw for the Pluto encounter was only 202 watts (about three and a half light bulbs). Each transmission draws only 28 watts (enough to power two small night lights.) Reception of these transmissions relies on super giant receivers—the Deep Space Network. There are only three in the world large enough—one in Madrid, Spain, one in Pasadena, CA in the US and one outside Canberra, Australia. The placement of them means that data can be received at any time as the earth spins on its axis. Last night’s transmissions were broadcast from Pluto four and a half hours before they were received, traveling at the speed of light and sent via the giant antenna dish in Madrid.

Alan Stern, the head of the New Horizons Mission and NASA’s chief investigator, told the gathering: “We did it! One small step for New Horizons, one giant leap for mankind.”

The audience included students who had been born almost ten years before on the day of the New Horizons launch. An elementary school boy asked, “Does this make Pluto a planet?” Fran Bagenal, NASA team leader for plasma investigations on the Mission, answered, “Yes! Of course Pluto is a planet!”

The Pluto mission began as a barroom bet by Alan Stern to prove Pluto was not just a dwarf planet but a full planet. The exploration was affirmed as a top priority by the National Academy of Science. In the audience last night were the grown children of Claude Tombaugh, the astronomer who originally discovered Pluto. Eighty-five years earlier their father told his senior astronomer, “I think I have found your planet X.”

Fifty years before to the day—July 14—humans first explored Mars with NASA’s Mariner 4. John Casani, special assistant to the director at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and one of the early engineers in the space program noted, “People developing spacecraft today know what they are doing. We didn’t know what we were doing. Back then the shoulders we were standing on were too narrow and our shoes were too big. We had only the technology for guided missiles.”

The scientists and engineers had to figure out, among other concepts, 3-axis stabilization. “Innovation was the key to making things work,” Dr. Casani said. “There was no book on 3-axis stabilization. We were all only a couple of years out of graduate school. We weren’t experienced enough to know that what they were asking us to do couldn’t be done.”

“You couldn’t go to the library and ask for a book,” added Norm Haynes, who was the trajectory engineer for the Mariner 4 Mission and also spent his career at NASA’s JPL. “There were no textbooks on how to build a spacecraft.”

There were no computers on board the first spacecrafts either. In 1962 the computer had only a 65,000-word vocabulary as opposed to the multiple gigabytes of memory today. The first computer was aboard Mariner 4 which delivered 22 pictures of Mars, each taking ten hours to send back. It took 60 hours to go to the Moon, 6,000 hours to go to Mars and now the New Horizons spacecraft can endure a nine and a half year journey to Pluto and still arrive in tact. The per mile cost of New Horizon was 25 cents/mile; the per mile cost of Columbus was $3000/mile and the per mile cost of Magellan was $5000/mile. On Mariner 4 in 1965 the spacecraft transmitted information at 8 1/3 bits / second; New Horizon transmits at 1000 bits/second and it is 60 times further away.

The scientists and engineers said the key to success was the willingness to imagine, to innovate and to be willing to fail. Considerable failures preceded this achievement.

Why is the exploration of Pluto important? It opens up our view of what is possible, of the universe and perhaps even of ourselves, suggesting larger horizons physical and metaphysical. It demonstrates the possibilities of human potential—of imagination and ingenuity empowered by cooperation, teamwork and a large goal. From a scientific point of view, from the point of view of NASA which has to secure the funding, it provides knowledge about the universe where we live and the universe beyond.

The data that will be gathered on the New Horizons’ close approach to Pluto is about 100 times more than can transmit before the spacecraft flies away. It will take 16 months to send all the scientific information home.

“We explore because we are human, but we want to know,” said noted physicist Stephen Hawking in a call-in message to the gathering.

If the next stage is funded, the New Horizons spacecraft will go off to explore the outer reaches of the Kuiper Belt, letting us know what lies beyond Pluto in the further reaches of space.

The spacecraft was built to last. Its power will endure until 2030, then it will not be sufficient to keep the instruments warm enough to operate, and the craft will drift into deep space. By 2030, the equipment on the spacecraft will be 40 years old and the innovations that will have developed by then we can now barely imagine.

Credits: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

What Are You Not Reading This Summer?

I was recently sent a questionnaire as part of a profile asking me what I was reading:

I find myself reading several books at the same time. I just finished Phil Klay’s Redeployment today, am reading Jennifer Clement’s Prayers for the Stolen, am re-reading Graham Greene’s The Comedians, re-reading Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this and can’t leave this question without noting Elliot Ackerman’s Green On Blue. Because I read both e-books and paper books, I move around among narratives easily.

The answer was a snapshot in reading time, indicative of the pleasure of dancing among narratives. I find myself enjoying on several platforms the movement between hard-edged, nuanced stories of war and its aftereffects in Klay’s Redeployment and Ackerman’s Green on Blue, the harsh and surprising world of Clement’s indigenous Mexican women in Prayers for the Stolen and the gentle, but no less desperate stories of Southern women trying to find their lives in Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this, a collection recently re-published by a new small press—Bacon Press—in paperback. Graham Greene is a master who I am always re-reading, appreciating how he integrates the international world of politics and deceit with compelling narratives set around the world.

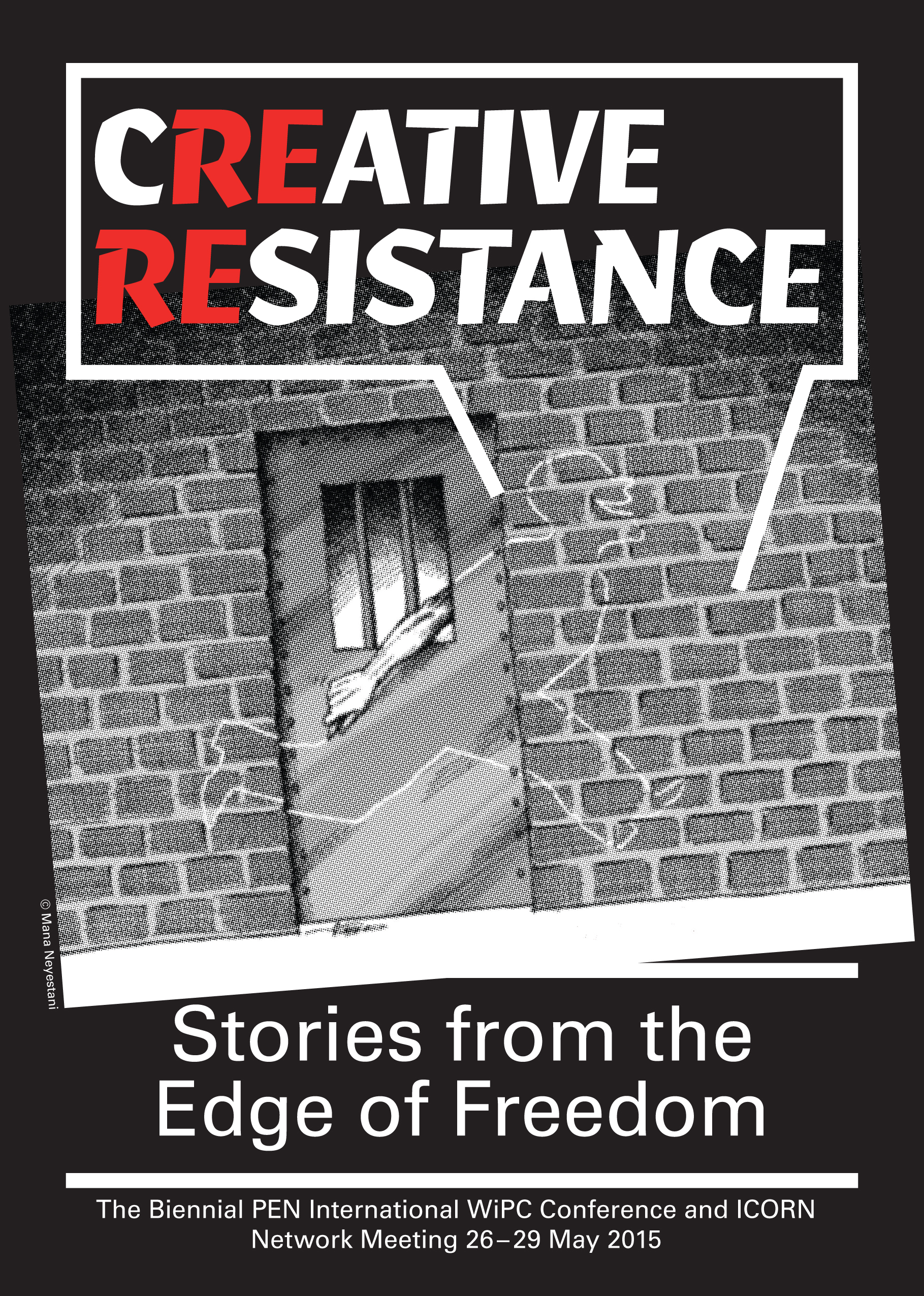

Recently I returned from PEN International’s biennial Writers in Prison conference and the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) meeting, a gathering this year in Amsterdam focused on Creative Resistance, a gathering of over 250 individuals from 60 countries around the world who work on behalf of writers threatened, imprisoned and killed for their writing. I remain conscious of these voices too. They occupy a kind of negative space—those we are NOT reading, not able to read because they are not able to write.

The list unfortunately is long, and many individuals stand out for me, but I will highlight two here. Though I couldn’t read either because of language differences, I read with attention their cases and link here to actions that can be taken on their behalf:

—Raif Badawi, a blogger and editor in Saudi Arabia, had his sentence confirmed this past week by the Supreme Court that he must serve 10 years in prison and receive 1,000 lashes for “founding a liberal website,” “adopting liberal thought” and for “insulting Islam.” Raif had planned a conference to mark “a day of liberalism,” and he launched an online forum, Liberal Saudi Network to encourage political and social debate. His lawyer has now also been arrested.

His wife, who fled with their three children, says she received threats from the Saudi embassy when she was in Lebanon that they would kidnap her children and forcibly return them to Saudi Arabia; the court verdict would force her to separate from her husband.

Though now living in Canada, she says, “I believe that there is a will for freedom in the country that will not be deterred.” Of the solidarity movements that support her husband, she adds in an interview with PEN International, “I used to believe it was a fantasy for a person to stand in support of another person regardless of geographical, racial, religious, linguistic and other differences, but what you have done for Raif’s case has taught me that I knew nothing about humanity.”

Link for more information and action.

—Gao Yu–Chinese journalist, former chief editor of Economics Weekly and contributor to the German newspaper Deutsch Wele and a poet–was arrested on charges of illegally obtaining state secrets and sharing them with foreign media and sentenced this spring to seven years in prison. When she was first disappeared, she was writing a column entitled ‘Party Nature vs. Human Nature,’ which is said to have considered the new leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and its internal conflicts. Gao Yu, who is 71, has been an intrepid journalist her whole career and an honorary director of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. She has often been at PEN conferences in Hong Kong and contributed to an essay in PEN’s 2013 report “Creativity and Constraint in Today’s China.”

She has served time in prison before, the first time for reporting on student protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and five years for reporting on political and economic issues in Hong-Kong based publications. She’s known for her critical political analysis of the inner circles of the Chinese Communist Party. Her arrest and sentencing has signaled to many the retreat from hope of wider press freedoms under the new leadership.

For those of us lucky to have met Gao over the years, we’ve seen she has a sharp mind, a smiling face and an unmistakable light in her eyes as though she is slightly amused and looking at a much longer narrative for China. At the recent PEN conference, each meeting had an empty chair on the stage, and a picture of Gao Yu as the honored writer not there.

Link to more information and action.