Posts Tagged ‘Slovenia’

Time of Repose and Preparing

It is a blustery August day on this fulcrum between summer and fall when the breeze stirs with a hint of the season ending. A pandemic stretching 18 months continues to unhinge life from what is considered normal, if there ever was normal. Life is far from normal in Afghanistan or Haiti right now. Normal is a relative term, residing perhaps in the hope for a measure of peace, for supply of basic needs and for the kindness of others.

This month I am again posting a retrospective of August blogs with a view of the last thirteen years’ history, a history which I read with nostalgia, recognizing those times are gone. It is difficult to imagine getting on a plane now to Tanzania or Kyrgyzstan or Macedonia with the same confidence of work to be done and the ability to meet those on the other end also engaging. The world may return as it was, though I’m not sure life ever returns as it was. But I hope it will transition to a world still connected and willing to connect and build with each other.

The geography of these posts range from Tanzania to Turkey to Qatar to France to Slovenia to Kyrgyzstan to Ghana to Macedonia and several in the United States. Readers can click on the date and title to read the full post. I am halfway through a year of posting these retrospectives and note that August is the first month where I’ve posted every year. I’m struck by the sultry beauty of this month between seasons, a time of repose and preparing.

Photo credit: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

August 31, 2008: From the Edge of the Indian Ocean

I’m sitting looking out at the Indian Ocean from the eastern edge of Africa in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. It is Labor Day, at least in the U.S., though in the U.S. it is actually still Sunday night; but here it is morning with billowing white clouds, blue sky, palm trees, sun shining through—the end of winter in the Southern Hemisphere.

It took 17 hours of flying and a few hours of waiting in Amsterdam—roughly 20 hours to get here. When I arrived in the hotel room last night and the bellman turned on the TV, the BBC in a pulsating picture and sound was reporting on the approach of Hurricane Gustav to New Orleans and the interruption of the Republican National Convention. Was this important news in Tanzania? It was, in any case, the BBC news, and I was interested but couldn’t help but note how far one can go and still have America follow.

Outside the window in the hotel this morning, men are cutting the grass by swinging machetes across the lawn. From a distance it looks as if they are practicing their golf swings, but in the morning sun they are tending to the grass without lawn mowers or power tools.

In the following days here and in Uganda I’ll have the opportunity to visit schools and projects where educators and writers are responding to the shortage of books for children, particularly books with stories relevant to the children and books in local languages. This morning I’m aware of the stories we carry with us, the narrative in our heads wherever we go, the power of this narrative in shaping our lives and the importance of listening to the stories of others and opening up the narrative.

“Once upon a time in a place where the sun usually shines and the winds blow through the palm trees, there is a little girl who lives on the edge of the Indian Ocean, and every morning when she wakes up, she…”

August 31, 2009: Turkey Can Avert a Tragedy on the Tigris

It can develop energy and progress into the future without washing away the town of Hasankeyf, its jewel of the past.

From The Christian Science Monitor

Washington – In the southeastern corner of Turkey near its borders with Iraq and Syria, environmentalists, human rights organizations, and archaeologists recently won a battle in the effort to avert a cultural tragedy.

Swiss, German, and Austrian firms pulled out of their contract with the Turkish government to build a dam that would flood and destroy a historical ancient city, harm ecosystems downstream, and displace thousands.

To permanently protect this area though, it should be designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Ilisu Dam, a cornerstone in a project to develop Turkey’s electrical and water capacities, is the largest and the most controversial of the 22 dams and 19 power plants scheduled in the $32 billion Southeast Anatolia Project.

At the heart of the controversy is the town of Hasankeyf, carved into the limestone cliffs above the Tigris River. Hasankeyf is reputed to be one of the oldest continuous settlements on earth, at least 10,000 years old, with relics found this summer that may date it to 15,000 years old.

In the Kurdish region of southeastern Anatolia, Hasankeyf has hosted at least nine civilizations, including the Assyrians, the Romans, the Byzantine Empire, the Mongols, and the Ottomans. On a central trading route in ancient Mesopotamia, Hasankeyf boasts more than 4,000 caves; 300 medieval monuments; 83 archaeological sites with ruins, including Hasankeyf Castle, built by the Byzantines in AD 363; and historic tombs and mosques. Its cultural and archaeological value is priceless.

Today the hillsides are dotted with artisans’ stalls, children on donkeys, and caves with restaurants inside.

If the Ilisu hydroelectric dam is constructed as planned 50 miles downstream, much of Hasankeyf – historic caves, ruins, and all – will be buried under 400 feet of water….[cont]

August 30, 2010: On the River: the End of Summer

Boats skimmed along the Potomac River this last weekend of August—power boats, yellow and red kayaks, boxy green canoes, sleek white sculls. I settled into the latter late Sunday afternoon, dropping oars into the warm water. Many in Washington are still out of town—on vacations or home visiting constituencies—but in their place are tourists exploring the nation’s capitol. The heart of the city beats on in festive cadence.

Baking in the summer sun, I eased leisurely down the river—past the Kennedy Center, the Watergate apartments, past the Georgetown waterfront where outside cafes were filled with people eating and bicyclists walking their bikes, past the new park along the river, then under Key Bridge, where a moment of shade brought relief. On the bridge above bikers and runners and cars crossed the river to and from Virginia. My scull sliced the surface of the water past the spires of Georgetown University, which peeked through the trees on the shore like a medieval fortress. I aimed out to the Three Sisters Islands, rowing with one oar to turn the scull then traversed the river, crossing the wakes of larger power boats so I could return on the opposite side, rowing past the nature preserve of Roosevelt Island towards the public boat house.

By the time I neared the home shore, sweat was dripping down my brow into my eyes, blurring my vision. The sun was slowly sinking in the sky, but relinquishing none of its heat. The boat house was already closing, and kayaks and canoes were pulled up on the dock; mine was one of the last sculls to return.

Summer is near its end. On Labor Day next weekend American flags will flutter beside the Potomac, and the political season with midterm elections will shift into high gear. But before the business of campaigns and politicians fill the air, summer may yet linger for just a bit longer like a temporary denouement before the pace of life accelerates. I take a moment here to savor the summer, which has been spent almost entirely in Washington—one of the hottest summers on record—a summer of writing, reading good books and welcoming into life a new grandchild. It has been a summer of quiet pleasures and great moments.

August 27, 2011: Before the Earthquake and Hurricane: Summer Music in the Afternoon

The air is surprisingly cool for late August. I’m sitting on an upstairs porch looking out over the tops of trees in their full dress of summer greens—maples, magnolias, dogwoods with white blossoms. The branches and leaves sway and rustle in the breeze. Somewhere a wind chime answers the moving air with a light ting and ringing like a message in the near distance, signaling the change of seasons. Overhead, shifting faces of white clouds drift through a blue sky, sliced by faint streaks from the trail of a jet that has long since passed by.

In this moment before evening, before the shift in seasons and the rush of autumn, I can almost hear the earth singing. Harmonizing with the wind chimes are thousands of crickets exploding with sound then quieting and birds sweeping through the sky calling to each other. The rustle of the trees, the call of the birds, the chirping of the crickets, the swoosh of the breeze are like nature’s symphony–an unexpected summer moment on this quiet August afternoon.

I sit high enough off the ground to see the sunlight golden on the tree tops and also to see the trees dark green, almost black, where the sun has left and the afternoon shadows have spread. I look down on the roses in a neighbor’s garden and look out on the brick chimneys of other neighbors’ houses.

I’m aware of the different voices of nature around me, each communicating its renditions of life, none of them taking notice of who will run for President of the United States, or who will emerge in power in Libya and Syria, or how the markets will close.

A flock of birds suddenly swoops past talking loudly to each other. What do they see and say and know?

[This post was written late afternoon Aug. 22. At 1:50pm on Aug. 23 Washington, DC shook as a result of an unusual 5.9 earthquake. As I edit this, we await the arrival of Hurricane Irene, characterized as a once-in-a-lifetime hurricane. The locusts, we hope, will pass us by.]

August 30, 2012: Diplomacy on a Summer Evening

It is a sultry evening at the end of summer in Washington, a backyard party on a patio with picnic tables on the deck, red Christmas lights strung across the porch and the night filled with animated conversation among ten Pakistani journalists and their American friends and hosts.

The journalists are soon returning to Lahore, Karachi, Balochistan, Islamabad and other cities and provinces in Pakistan. For the last month they have been working in newsrooms across America. Most are here for the first time, witnessing and learning about American culture and sharing their own culture and experience. They have worked from Tallahassee to Tucson to Los Angeles, from Washington, DC and Baltimore to Providence and Pittsburg; one journalist reported from Minnesota. They have covered American elections, crime, state politics, the judiciary, education and economics.

The Pakistani journalists have also met with the communities, including addressing hundreds of members of the Rotary Club in Tallahassee and having a one on one discussion with a Catholic bishop about abortion.

In their month they all agreed their misperceptions of America were changed.

–I thought Americans would be rude, said one and others agreed that that was their preconception. Instead they were friendly and helpful everywhere.

–They were very friendly, said another, but in Minnesota, they had little knowledge of Pakistan and held some myths.

–When people think of Pakistan here, they think only of terrorism. That was the general misperception.

–I saw how hard Americans worked. I always thought Pakistani journalists were energetic, but an American newsroom—that is energetic!

–I lived with the executive editor, and we were in the newsroom by 7am.

–I was impressed by the huge facilities in American newsrooms. The journalists are very professional. But I come away very proud of my fellow Pakistani journalists who work in much worse conditions.

–I was surprised that 50% of the staff was women. I even had a woman driving me.

The International Center for Journalists will bring 160 Pakistani journalists to work and live in the United States, and has sponsored American journalists into Pakistani newsrooms.

As we shared chicken tandori and lamb sausages and curries and rice in the fading summer light, the guests all agreed that this type of professional exchange opened and advanced relations between people in a way that politicians can’t or don’t.

–I covered the Governor and State legislature, said one reporter. The Governor was lobbying for his bills, especially to get his bill passed on gambling. It was just like Pakistan!

August 21, 2013: Peacocks and Politics

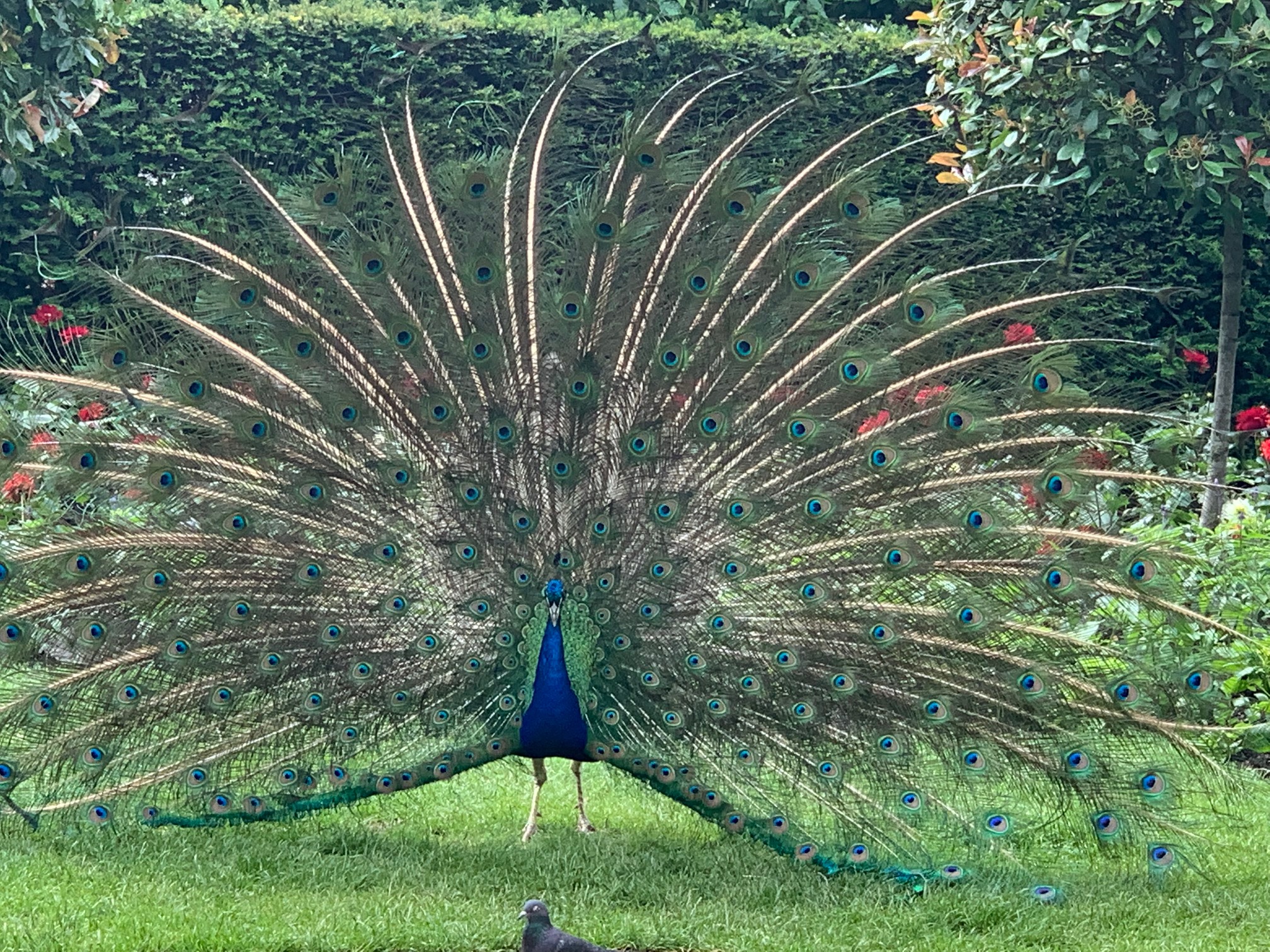

I’ve spent much of the summer on the Eastern shore of Maryland on a river, writing and listening to the quiet lapping of the water against the stones of the river bank, except when jet skis whish by and when the peacocks next door caw and caw at the neighbor’s farm. The peacocks call to each other all day long, broken by a rooster’s cock-a-doodle-do…actually the rooster is yodeling now, though I don’t know what he’s heralding in the middle of the afternoon.

The peacocks wander over from time to time, running across our yard like stealthy children hiding from their parents. I don’t know what prompts their visits. They usually leave a mess, but their brilliant feathers swishing by always surprise and astonish me.

Today as I was moving to a table outside to write this blog, I discovered one of the females nesting, hidden in a bush outside the house and, I believe, hatching a brood of eggs. I don’t know when she arrived, but she lay there motionless as though she had gone into a deep sleep, moving not at all as she protected her eggs. I’m not sure how long gestation is for peacocks, but soon we will be host to baby peacocks! Since the birds wander from farm to farm, no one claims ownership, certainly not me, but suddenly I feel a responsibility, for exactly what, I can’t say, at least a responsibility to give the mother the peace and quiet she has sought by escaping here, away from the other peacocks and roosters. Occasionally we have a dog visit on the weekend so my first responsibility is to make sure the dog doesn’t find the peacock….[cont]

August 2, 2014: Poets, Pardons and Ramadan

(This piece appears on GlobalPost.)

Eid—the end of Ramadan—has come and gone. Traditional pardons have been handed out. In Qatar, poet Mohammed al Ajami (Al-Dheeb), was not among them. He continues to live in a prison in the desert, serving a 15-year sentence for two poems, one praising the Arab Spring and the other critical of the Emir. He (and his poems) “encouraged an attempt to overthrow the regime,” according to the charges.

The over 70 pardons granted in Qatar are reported to have gone to Asian workers charged with theft, rape, drug abuse, bribery, prostitution, etc. These workers will now likely be deported. If Mohammed al Ajami were released, he would also likely leave the country to reunite with his family and then perhaps accept a brief fellowship offered as a poet at a major university.

Throughout the Muslim world Ramadan is a time when dispensations are handed out— as many as 1000 prisoners reportedly released in Saudi Arabia, 800 plus in Dubai, over 350 in Egypt— to individuals charged with violent and nonviolent crimes. But the amnesties were not given to writers, not to poet al Ajami, not to Egyptian journalists or Iranian bloggers. The offense of words and ideas are perhaps judged more dangerous.

Writers in prison in the Middle East who did not get pardons include: Bahrain (3writers), Egypt (5 writers), Iran (35 writers), Qatar (1 writer), Saudi Arabia (2 writers), Syria (11 writers), Tunisia (1 writer), United Arab Emirates (2 writers). *

August 27, 2015: “What to Read Now: War Narratives”

From the September/October 2015 issue of World Literature Today

While the US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been going on for fourteen years, much of American literature from these conflicts is only now emerging. I appreciate the veterans who’ve woven the simultaneously “worst and best days of their lives” into literature. They have turned to all forms to find their truth—poetry, short stories, memoir and the novel. (Disclosure: I’m the mother of a Marine who served in both conflicts and is now one of the novelists listed here.)

I have framed these suggested readings with a history from the Great War a hundred years ago and with a diary of one of the long-serving detainees in Guantánamo. Truth in literature is determined in part by point of view. In these books, the reader can take a journey from many perspectives.

Margaret MacMillan

The War That Ended Peace

Random House

In this nonfiction book, Margaret MacMillan narrates history through the lives of those responsible for World War I. The characters and cousins could populate a fiction collection with their dramas, imaginations and absurdities. MacMillan offers an inside view, revealing the people and stories behind the politics and events that led to a war many feel—and felt at the time—shouldn’t have happened.

Brian Turner

My Life as a Foreign Country: A Memoir

W.W. Norton

The author writes of his deployment as an Army sergeant, beginning in the US learning to identify body parts, watching combat on television, and then arriving in Iraq and facing real combat in the first Stryker brigade. “We rode on a war elephant made of steel,” he writes of the nineteen-ton tank. A poet (Here, Bullet), Turner narrates his experiences and his return home in a poet’s language, which spins the harshest circumstances—the soggy, trodden straw—into gold and art.

Phil Klay

Redeployment

Penguin Press

A veteran of the US Marine Corps assembles a dozen short stories and first person narrators—soldiers on the front lines, in the rear, at desks, with their family, friends, wives and girlfriends back home. The narrators’ voices are witty, unflinching, nostalgic, and the stories make the reader laugh, cry and wonder how a generation honed on this conflict will return to life as it was.

Elliot Ackerman

Green on Blue

Scribner

This novel narrates the war in Afghanistan from the point of view of an Afghan orphan who gets caught up on the American side of the conflict in order to keep his brother alive. He quickly learns that the war has too many sides and so many points of view that truth shimmers only in the eyes of the beholder.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Larry Siems, ed.)

Guantánamo Diary

Little Brown

Guantánamo Diary tells the story of the “war on terror” from the point of view of one who has been detained, tortured, and continues to proclaim his innocence. With a literary and humane voice, Slahi, edited beautifully by Siems and redacted by a censor, renders the horror and humanity in this war that will not end.

August 11, 2016: Sounds of Summer

(This is not a poem)

August on the Eastern shore

Quiet on the river

Birds chirruping in the trees

Crickets—or are they cicadas—clicking in the afternoon, clicking that will build to a crescendo in the evening

CaCaCa of peacocks next door

Water trickling, flowing slowly out to the bay

A power boat whishing by, heading to the open water

A leaf blower, a lawn mower in the distance, jarring the quiet

Leaves rustling in the breeze

Breeze skimming the trees, rustling, rushing louder now, emboldened

More birds chirping, the beginning of a larger conversation

At the very top of a tree at the river’s edge a black bird keeps watch, looking first out to sea then to land, then trips lightly along the branches, lets out a caw and flies away.

I sit here, listening to all these sounds of late summer.

I sit here, listening to all these sounds of late summer.

Soon the children will come home from camp, run outside, filled with their day—karate lessons, swimming, new friends—but for now in the quiet, I am “happy in my circle of oblivion,” to borrow a phrase from Garcia Márquez, whom I’m reading on this rare, undisturbed afternoon.

The news—the sturm and drang of presidential politics, the daily offenses—are outside this space on the river. For a brief moment the troubles of the world seem held at bay. Even the trials and triumphs of the Olympics must await the evening news.

I watch three billowing white clouds drift by ever so slowly in the blue sky.

As the breeze picks up, the trees rustle, continuing a conversation, stirring first one tree then another, passing along the wind’s gossip down the river bank.

If this light wind holds, it will be good kite-flying weather in the evening. We can have another picnic by the river with grandfather sitting in the Adirondack chair and everyone else on the grass—hot dogs, hamburgers, corn, applesauce, kite in the air, children running, laughing.

The parade of clouds drifts by overhead now like characters in the children’s play they plan for the grownups. “One, two, three…look at me!” The black dog passes all dressed up to play a part in the drama as he looks for scraps from dinner. The shapes of the clouds pass and just blue sky shines overhead. We will end the evening with S’mores at the fire pit as the moon rises over the river.

There are only three more weeks of summer—more books to read, stories to write, laps to swim, thoughts to think before the demands of schedules and meetings and deadlines crowd in.

For this moment I am grateful for the silence, the breeze, the birds, the river, the shining sky, the billowing clouds and the promise of this afternoon that I will carry with me.

August 14, 2017: The Beginning of Violence

In the wake of events in Charlottesville, Virginia last weekend, I wanted to share my short story “The Beginning of Violence” set at the first sit-in in Nashville, TN in 1960, published in No Marble Angels and republished in Short Stories of the Civil Rights Movement: An Anthology (ed. Margaret Earley Whitt, University of Georgia Press, 2006.). The anthology includes 23 short stories by black and white writers—stories of the heart, not just politics—an historic journey worth embarkation.

THE BEGINNING OF VIOLENCE

by Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Nashville, 1960

The wind shot through you that day like fate or some might say like the will of God. No matter what you did, it got you. It weaseled under the buttons of your coat, pulled off your scarf. You couldn’t fight against it though you could stay indoors, but once you came out, you had to face the wind and find your way.

It was the day before Valentine’s, and snow was falling in thick wet flakes, had been since early morning and threatened to keep on all afternoon. As I said, it was not a day to be outside, but I was. I was downtown on the arcade doing last minute shopping for a sorority party that night. We’d been decorating all morning, but we’d run out of crepe paper and balloons; and Janie, the food chairman, was afraid she’d run out of paper plates and cups so I said I’d go downtown and pick up everything.

I went to Woolworth’s. At the Grand Ole Opry counter I bought a red plastic guitar set inside a big red plastic heart for the centerpiece on the officer’s table. I was an officer. I was treasurer of the Kappa Alpha Thetas at Vanderbilt University.

I didn’t feel like turning right around and going back into the cold so I stopped at the lunch counter for coffee and a grilled cheese sandwich. I was sitting there eating and reading “When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d” for English class when a blast of air swept across my back. When I turned to see who was holding the door open, I saw dozens of Negroes coming into the store.

They moved straight down the aisles then disappeared among the cheap jewelry and face powders and school supplies.

I turned back around and finished my sandwich and Whitman’s poem. I was about to pay and leave when three Negroes sat down at the counter, one of them next to me. They all held brown paper bags with purchases they’d made. The girl beside me smiled, showing a curve of white teeth and asking more than most people thought she had a right to ask. I looked over my shoulder and saw thirty or forty more Negroes lining up to sit at the counter.

It took me a minute to understand what was happening. I’d grown up in Arkansas and Tennessee, and in nineteen years I’d never eaten beside a Negro. I’d never sat next to one on a bus or gone to the same bathroom. Things were changing in the South, but these were facts I’d lived with. Once in high school in Little Rock I’d signed a petition favoring integration, and that had almost gotten me thrown out of cheerleading. Some people thought anyone for the Negro was a Communist. I wasn’t a Communist; I just thought the Negro should have a chance. And yet even feeling that way, I wasn’t prepared to have the order of things put to question right where I was sitting.

The girl kept smiling. She had a soft mouth and big, dark eyes. Her hair was straightened, and she wore it like mine, in a pageboy with bangs. She was taller than me, and under her coat she looked strong. When she saw my poetry book on the counter, she reached into her pocket and took out a copy of the same book. I couldn’t help but feel she’d just drawn her gun…[cont]

August 3, 2018: Peace: Fabric with a Million Threads

Earlier this summer I had the opportunity to moderate a panel of high school teachers at the United States Institute of Peace called “A Year in the Life of a Peace Teacher.”

United States Institute of Peace in Washington, DC

On that morning of July 10 two positive news events broke: the final young soccer players and their coach, who had been trapped for almost two weeks, made it out of the caves in Thailand. And Liu Xia, wife of Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese Nobel Peace Laureate who died last year in custody, landed in Europe, released after a decade of virtual house arrest in China.

For me these events connected to the panel on the teaching of peace-building.

Was peace possible? Could peace be “built”? The answer we concluded that morning with cautious optimism was: Yes.

The miraculous rescue of the soccer team resulted because highly skilled citizens from nations around the world, including the U.S., Australia, Denmark, Britain, China and most importantly Thailand came together and exerted their best efforts with a common goal everyone agreed on.

Freedom for Liu Xia resulted in large part because citizens and politicians around the world spoke up and advocated on her behalf though a similar effort had not won the release of her husband.

That morning, listening to the teachers and their work with students reinforced a view that peace was not just building bridges between two opposing pylons or signing treaties, but was the weaving of hundreds, thousands, millions of threads, of each citizen taking responsibility within his/her own community.

Each year the U.S. Institute of Peace, founded in 1984 as a nonpartisan Institute to promote peace and resolution of conflicts around the world, also focuses on the U.S. and selects four high school teachers for year-long training which they take into their classrooms. They work on problem-solving and peace-building in their communities and also study global peace opportunities.

This year’s teachers from Missouri, Montana, Florida and Oklahoma shared ways they and their students ignited discussion in their classrooms and in their communities and then took initiatives relating to issues of race, immigration, etc. They emphasized the understanding that peace didn’t mean avoiding conflict but rather finding ways to engage nonviolently and then to find ways to resolve conflicts by listening, determining the interests of the other, showing empathy.

Specific stories of the teachers and their journeys with their students can be heard on this link.

To conclude the panel it was appropriate to quote Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo. In his career and in his final statement to the court before he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for his writing and work towards democracy, he told the judge: “I have no enemies and no hatred.” In his life Liu explained that to build a society without hate, one had to begin with one’s self. After he died in custody last year, many questioned whether he would have claimed this had he known his end, but those who knew him well said he would have because he believed the responsibility for a peaceful and fair society began with oneself.

Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people… It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, it can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.

It was poignant and fitting that day to see Liu Xiaobo’s wife Liu Xia’s smile as she landed in Helsinki.

August 2019: [Beginning in May 2019 I started writing a retrospective of work with PEN International for its Centenary so posts were more frequent in 2019-2020. In August 2019 there is one post in the PEN Journeys and in August 2020 there are three.]

August 1, 2019: PEN Journey 7: PEN in Times of War and Women on the Move

Iraq invaded Kuwait August 2, 1990. When I picked up my 10-year-old son from camp in the U.S. that summer and told him what had happened, his first response was: What about Talal and Alec? These were two of his good friends at the American School in London—one was son of the Kuwaiti Ambassador; the other was from Iraq. He quickly understood the consequences. Fortunately, both of his friends had been out of their countries at the time, though I don’t recall Alec returning to the American School that fall. When the bombs dropped on Baghdad in January, the American School went into lockdown. The older students were issued identity cards. The security force around the school multiplied. When Talal came over to play that winter, he was accompanied by two imposing bodyguards who stayed outside.

Though the fighting in Iraq concluded by the end of February, security in London continued. By the end of March, the war in the Balkans had begun. Both wars brought to a close the honeymoon many felt after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

For PEN, the outbreak of war in Iraq and in the Balkans led to the cancellation of the planned Delphi Congress and to the convening of conferences in Europe and a two-day gathering of PEN’s Assembly of Delegates and international committees in Paris in April 1991. Delegates from 39 PEN centers came together to conduct the business of PEN at the Société des Gens de Lettres de France which occupied the 18th-century neoclassical Hôtel de Massa on rue de Faubourg-Saint-Jacques in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. There were no literary sessions or social gatherings, or the usual simultaneous translation of proceedings. The business was conducted primarily in English with intermittent French, the two official languages of PEN. (Spanish was added a few years later as PEN’s third official language.)

The Gulf War, the ethnic conflict in the Balkans, the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square trials and the ongoing fatwa against Salman Rushdie predominated discussions in Paris and later in November at the 56th PEN Congress in Vienna. The Gulf War had resulted in increased numbers of writers imprisoned and killed in the Middle East and an increase in censorship. Resolutions condemning the detention and imprisonment of writers in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Israel and Turkey passed the Paris Assembly. Little information was available from Iraq. Another resolution in Paris sponsored by the two American centers expressed concern to the U.S. government and all U.N. member states over the restrictions placed on journalists during the war and urged a review of the ground rules for journalists in conflicts….[cont]

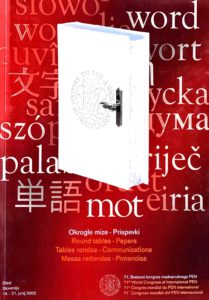

August 5, 2020: PEN Journey 37: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part Two

At PEN’s 71st World Congress in June 2005 over 275 writers from 88 PEN Centers gathered from around the world in the idyllic setting of Bled, Slovenia where history had been made 40 years before. In 1965, PEN had held its Congress in Bled, the first in Eastern Europe since the Second World War. Russian writers visited PEN for the first time. At that 33rd World Congress, American playwright Arthur Miller, who’d recently passed away in 2005, had been elected the first and only American President of International PEN.

Lake Bled in Bled, Slovenia, site of PEN International’s 71st World Congress, 2005

In 2005 the global dynamics had changed. PEN now had active centers in most of the countries in the former Communist Eastern bloc, including in Russia. The European Union (EU) was in its ascendancy; 2005 marked Slovenia’s accession into the EU. Globalization was bringing benefits but also threats to the cultures of smaller countries.

Reception 71st PEN Congress in Bled, 2005. L to R: Frank Asare Donkoh (Ghana PEN), Jane Spender (Program Director PEN International), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Secretary), Alfred Msadala (Malawi PEN), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (PEN Executive Director), Dan Khayana (Uganda PEN), Bao Viet Nguyen-Hoang (Suisse Romand PEN) [Photo credit for many photos: Tran Vu]

“We live in an age when many preconceived ideas, nurtured for centuries and ostensibly immutable, are no longer valid,” noted Slovene PEN President Tone Peršak. “The linguistic and cultural image of the world is in flux and civilization as a whole, under the influence of globalization, is taking on a new character. These events are also echoed in discussions within PEN centers…They guided us in our selection of the main topic for discussion at the Congress, namely the issue of linguistic and consequently cultural diversity of the world. The topic is proposed as a question: does linguistic diversity stimulate or hinder cultural development? Is it a curse or a blessing that made possible the emergence and encounter of various world views, different emotional responses to the human destiny, and finally also brought about the formulation of different schools of thought and philosophical doctrines?

“We regard the question of linguistic and cultural diversity also as a human rights issue. Attempts to unify and subject all aspects of life to uniform standards and norms is viewed as a very questionable encroachment on these rights. One of the topics is therefore the question of the need to protect languages and cultures, and that means also the smallest ones which may be on the verge of extinction. Let us also draw your attention to literature’s role in the preservation of the memory of the cultural landscape, which has been undergoing considerable changes and in some cases may even disappear forever…[Is] literature a kind of lingua franca which could and should contribute to a better mutual understanding and insight into the different cultures and nations that sustain cultural diversity?…”[cont]

August 14, 2020: PEN Journey 38: PEN’s Work On the Road in Kyrgyzstan and Ghana

There have been a number of conferences and a few Congresses in PEN I’ve regretted not being able to attend. One was the Women’s Committee conference June 2005 in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan right after the 71st Bled Congress. As International Secretary, I have notes and reports from that conference. Nine years later in the fall of 2014, PEN held its 80th World Congress in Bishkek, a Congress I did attend. The Women Writers Committee led the way for International PEN into Central Asia. Later in 2005 members of the Women Writers Committee also met at the International PEN conference in Ghana which I did attend.

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, site of PEN International’s Women Writers Meeting in June 2005 and Accra, Ghana, site of PEN International’s African conference and also meeting of African women writers, November 2005.

First, Bishkek: The President of Bishkek PEN Vera Tokombaeva was concerned about the circumstances of writers in Central Asia since the breakup of the Soviet Union. She suggested to the new Women Writers Committee (IPWWC) chair Judith Buckrich that PEN hold a women writers meeting in Bishkek. Many of the institutions which had enabled writers to publish had vanished, and the status of women in the region had grown worse. Young writers from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan who were members of the PEN center were troubled by the decrease in the number of women working creatively. Only a handful were left.

PEN Women Writers Committee Chair Dr. Judith Buckrich and International PEN Board member Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN)

Bishkek PEN did a study highlighting the problem. Central Asian women writers were struggling with poverty, it said, and literature was no longer published unless self-published with limited distribution.

“Women writers are now mostly on their own. They have fallen into a cultural vacuum,” the conference proposal noted. “They are not in contact with colleagues outside their own country and know nothing of the state of culture in the world. In the meantime the global community has begun to pay attention to Central Asia because its difficult geopolitical situation could lead to the rise of violent, ultra-religious and fundamentalist ideologies into the area. And it is partly the lack of modern local literature that makes the region a breeding ground where alien ideologies can take root among young people. Flourishing modern literature could be the means to disseminate democratic ideas and social awareness….”[cont]

August 31, 2020: PEN Journey 39: Spiritus Loci—Literature as Home

[From address at Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee Conference September, 2006:]

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia.

Last year at this conference, I packed in a rush, left behind a pair of shoes, but in the process got a title for a story.

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia.

I don’t yet know what story will emerge, or maybe only this brief talk will emerge, but Macedonia makes the title work, at least to my mind. I Left My Shoes in England…that doesn’t work…I Left My Shoes in France?…No. I Left My Shoes in the United States…please. I look forward to discovering who left the shoes and what the circumstances were and most of all what Macedonia has to do with the story.

Ohrid, Macedonia, setting of PEN International Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee conference, 2006.

Exploring the conference theme spiritus loci will be part of the journey. As writers we know the power of place in literature and in our lives. The Latin term meaning the local spirit of a place is not always easily defined, but it relates to the geography, the history, the architecture and the people, who are both shaped by and shape the place. The ancient Romans thought every location had a spirit, some benign where people would live longer, happier lives and some evil and destructive of human well-being.

Today in a world grown smaller and more connected by jet travel, the internet, the global village, the cyber global village, with the blending of cultures and commerce worldwide, spiritus loci is perhaps a more fluid concept and to a younger generation, even a digital concept. On the internet I discovered a recording studio with the name Spiritus Loci; it moved from place to place recording people’s music wherever the musicians felt most comfortable.

Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) Dimitar Basevski (President Macedonian PEN), and Kata Kulavkova (Macedonian PEN & Chair PEN International’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

It is still the writer who can best capture a place and a people and render that spiritus loci for the reader. The best writers unveil the unity between location and character so that the writer’s version becomes the backdrop for understanding the place for generations to come, whether it be Tolstoy’s Russia, Balzac’s France, Dickens’ England, Achebe’s Nigeria, Toer’s Indonesia, Fuentes’ Mexico….[cont]

PEN Journey 36: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part One

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

In pulling out papers from 2005 of PEN conferences and the 71st World Congress, I came across two documents that told a very human story in PEN and a coincidence of life that I share here:

71st PEN World Congress 2005, Bled, Slovenia, Round Table Papers

The first paper I skimmed was a talk I’d given as PEN International Secretary at the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee Conference in Ohrid, Macedonia in September 2005; the paper included the testimony of a PEN member at the end. The second text I read was from the Round Table Papers of the PEN Congress a few months before, in June 2005. This paper was on the Congress theme Tower of Babel: Blessing or a Curse? The paper was the first in that publication and was written by celebrated Nigerian poet Niyi Osundare who speculated on what the world would be should there be just one language and then meditated on what in fact the world was. Shared below are excerpts from Dr. Osundare’s paper, “The Blight and Blessing of Babel:”

“A one-language world would be too simple, too linguistically neat, too unrealistic. And, I daresay, too unnatural. For everywhere in nature there is a tendency towards fission and mutation on an intra-and inter-generic basis. Variety is not only the sauce of life; it is also its source…

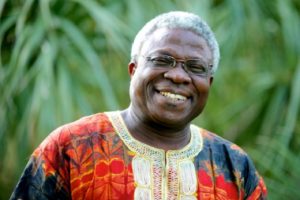

Nigerian poet Dr. Niyi Osundare

“Yoruba culture (the culture in which I was born and raised, and one that I know best) understands the necessity of diversity and inevitability of varieties in different aspects of human life. Hence the saying “Mee l’Oluwa wi” (Many, says the Lord) and “Ona kan o w’oja” (There are countless routes to the same market), both of them short, handy variations on a longer proverb “Oju orun t/egberun eye fo lai farakanra (The sky is wide enough for a thousand birds to fly without colliding). Corroborating this pluralist perspective is the folktale about the Tortoise, ever cunning and self-centered, who one day decided to capture all the wisdom in the world and seal it up in one pot for his own use in an effort to become the wisest being in the world. Of course, his project ended up in a laughable disaster as his pot fell to the ground and exploded while different fragments of the imprisoned wisdom dispersed in different directions, free for all, unmonopolisable. In an essentially pluralist Yoruba worldview, phenomena exist by mutual definition; a thing, a person loses its sense of proportion when there is nothing else to compare it with. The trajectory of life hardly ever follows one straight and narrow path; it must confront the crossroads, experience the thrills and tortures of decision and indecision, before arriving at the juncture of choice. And for the act of choosing to take place, there must be more than one…

“Literature (and the arts generally) is, no doubt, a powerful weapon in the struggle against the blight of Babel. By endowing our airy thought with that ‘little habitation’ and ‘name’ (hail Shakespeare, one of the supreme healers of the wounds of Babel), by generating universal sympathies, globalizing the particular and particularizing the global, by producing that music of the spheres whose winds stir the eaves in different lands, by evoking images which touch hearts across cultures, by articulating those humane values that are essential to human freedom everywhere in the world, by constantly lifting the human spirit and enriching, interrogating human reality with the supple possibilities of fiction…literature strives to restore some of the lost potentialities of Babel. For every significant writer is a bridge-builder of a kind, a witness, a participant-observer, an advocate of a truly humane future.

“No doubt, the phenomenon of Babel has left its fragmentations and dispersals. But it has also bequeathed to humanity a panoply of sounds and letters, an astounding (even if confounding) array of tongues which challenges the tyranny of uniformity and monotony of methods. It has necessitated the building of bridges across diverse tongues and cultures, these bridges being, in a way, a horizontal alternative and antidote to the vertical impossibility of the Tower itself.”

L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary) and Kata Kulavkova (Chair PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

Dr. Niyi Osundare, a Nigerian PEN member, had moved to New Orleans for specialized education for one of his daughters and was also a member of the African Writers Abroad PEN Center. Recounted here is my talk to the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee a few months after the Bled Congress, in September 2005. Only as I recently read the end of my paper did I grasp the connections and the range of PEN’s reach and work. My observations at the time:

The theme of the 8th Ohrid P.E.N. Conference—Writer Within and Without a Homeland—struck a particularly sonorous chord as I was preparing to come here.

In the U.S. the question of homeland has been on the national consciousness for the past month as one of America’s most diverse and multi-lingual cities—New Orleans—has literally disappeared. Its population evacuated as the city sank into the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. A large portion of the Gulf coast also fled in the face of Hurricane Katrina. Over a million people dispersed throughout the land in one of the largest displacements in the nation’s history. Many will never return to their homes.

In Europe and Africa, Asia and Latin America even larger displacements have occurred in the last century, often because of war, famine, politics, and also weather. All of us remember the disappearance of towns and villages and whole sections of coasts in the countries hit by the tsunami last December.

When a home is suddenly gone, family scattered, livelihood and career and ambitions all uprooted, one is forced to consider what endures, and what one can take with him. Home moves from a physical place to a place in consciousness.

The ability to speak with others and to tell the story is especially important and makes the idea of language as homeland compelling, also imagination as homeland, literature and art as homeland, and particularly relevant to PEN, a community of fellowship as homeland.

I’d like to read a message to PEN’s Africa Writers Abroad Centre from a Nigerian writer trapped in New Orleans:

This is my first real internet access since the disaster struck…I can’t thank you enough for your concern and care. It’s been all so overwhelming. My wife and I are alive and, after passing through five horrendous “evacuation centers”, have been allocated to the Red Cross shelter in Birmingham, Alabama. The nightmare of the past seven days is simply unimaginable. We very narrowly escaped drowning in our own house. Pursued by an 8-foot high toxic flood water (15 feet in the street outside our door), we were forced up a stuffy, airless attic, where we were holed up for 26 hours, with no food, no water, no prospect of any rescue. We were only saved by the fortuitous intervention of a neighbor who heard our shout for help when he came round with his rescue boat to pick up something from his own house. With life vests provided by him, we managed to swim out of our house, leaving everything we had behind. Right now, all our clothes, books, academic and professional credentials, travel documents, computers, manuscripts, etc are submerged in the dirty waters of the New Orleans flood. Hell has no other name… We deeply appreciate your concern. Kindly pass on our gratitude to all on your list serve.

Yours in the Eye of the Storm

[Niyi Osundare]

I’m told he has been overwhelmed by the outpouring of concern. While the concern and offers of assistance can’t replace what was lost, it can fill in some of the spaces in the heart.

In the U.S. those displaced are at least relocated in the same country and for the most part speak the same language, though the difference in accents has its challenges. What has been heartening has not been the help of government agencies, but the outpouring of citizens in communities all over the nation and abroad. One would wish this empathy would prevail and continue.

The ability to imagine and to reach out to another and try to see from the other’s point of view is one of the elements of great literature and also of great people. This empathy is a value around which PEN has developed and one which PEN at its best embodies.

A community spread across 99 countries, shaped by different nationalities, cultures, races, religions, and languages, PEN is a fellowship of writers who appreciate the importance of telling a story and defend the writer’s freedom to tell it as he sees it and to tell it in the language of his choosing. Language is the writer’s tool, expressing the music of his thoughts and sounding the chords of his imagination.

Language, imagination and fellowship—all are a kind of homeland that can survive the elements and can even survive politics and war, a homeland, one of whose addresses we like to think is at P.E.N.

Dr. Osundare and I didn’t know each other at the time though perhaps met briefly at the Bled Congress which was attended by more than 275 writers. I know many of his colleagues from Nigerian PEN and at the time from the African Writers Abroad PEN. I made the connection only as I reviewed the papers. Dr. Osundare is now a professor at the University of New Orleans.

Delegates at PEN International World Congress, Bled, Slovenia, June, 2005. L to R: Remi Raj (PEN Nigeria), Dan Kayhana (PEN Uganda), Frankie Asare Donkoh (PEN Ghana), Alfred Msadala (PEN Malawi)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 37: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part Two

PEN Journey 14: Speaking Out: PEN’s Peace Committee and Exile Network

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

With a blue glacial lake surrounded by the Alps, a small island in the center with an ancient church with a Wishing Bell that rang out and promised fulfillment for the wishers, with a castle perched atop a hillside—with beauty and history intertwined through the landscape, Bled, Slovenia offered a stunning venue for PEN International’s Peace Committee meetings.

Bled, Slovenia

In the heart of Europe, the Peace Committee sat in the heart of a contradiction, for there were few places less peaceful than the Balkans. Yet Slovene PEN members played an important role as did other PEN members in bridging divides among writers in conflict zones.

At the Peace Committee’s inception in 1984, Slovenia was part of Yugoslavia, one of a handful of Communist countries after World War II whose writers were able to sign PEN’s Charter which endorsed freedom of expression. The other countries included Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Hungary. In 1962 a well-known Slovene writer, who was a member of English PEN but returned each year to Slovenia, championed the idea of resurrecting the Slovene PEN center which had existed before the war as well as the other two Balkan PEN Centers—Croatia and Serbia.

In 1965 writers from these Yugoslav centers took on the task of staging an International PEN Congress in Bled. At the congress Arthur Miller presided as the first and only American President of International PEN. At the ’65 Bled Congress PEN also hosted for the first time Soviet writers as observers. “Almost despite myself I began feeling certain enthusiasm for the idea of international solidarity among writers, feeble as its present expression seemed,” Miller wrote in his autobiography Timebends. “…I knew that PEN could be far more than a mere gesture of goodwill.”

It took almost 25 years before a Soviet, and later Russian, PEN Center emerged. [see PEN Journey 3, 6, 8] During the Cold War it was difficult for writers from the East and West to communicate, but at PEN congresses and meetings and at the Peace Committee, writers debated, exchanged ideas and shared literature. The Peace Committee became a haven during the Balkans War and also a meeting ground for writers from other conflict areas.

Unlike the Writers in Prison Committee which worked to protect and liberate individual writers, it was difficult at times to define the concrete actions the Peace Committee could take, but at least three stand out in my memory—one direct action, one initiative and one rigorous debate on a pressing issue.

As noted in an earlier post [PEN Journey 7] the head of Slovene PEN, Boris Novak ran the barricades during the Balkans War with aid for writers in the besieged Sarajevo as did Slovene poet and future Peace Committee Chair Veno Taufer and others. At the Peace Committee meeting in 1994 Boris reported 100,000 DEM ($60,000) had been contributed from PEN centers around the world and delivered to almost 100 Bosnian writers in order to save lives. When a new Bosnian center was elected at PEN’s Congress in late 1993, the Bosnian center began taking over the delivery of aid, and Boris was elected chair of the Peace Committee.

Boris Novak. Photo credit: The Bridge Magazine Veno Taufer. Photo Credit: Alchetron

I attended my first Peace Committee Conference as Chair of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee in 1994 at the midway point of the Sarajevo siege. At the time PEN was also being asked to help writers who managed to get out of the city. In London I’d met one of these Bosnian writers and gave him my son’s old computer which he accepted as if I’d given him the keys to the city for he had no means to write. Writers fleeing not only the Balkans but situations in Africa and the Middle East needed support as they landed in new locations. It was at the Peace Committee meeting in 1994 that PEN’s Exile and Refugee Network was first conceived in partnership with the Writers in Prison Committee. The initiative was confirmed at the PEN Congress later that fall in Prague.

This initiative for exiles and refugees moved into an exploratory phase which became a leit motif in PEN’s work over the next two decades as it had been in the decades past. PEN’s Exile Network, spearheaded by PEN Centers, including Canada, Sweden, Norway, Germany, Belgium, England, America and many others took the initiative and offered residencies, aid and services to refugee and exiled writers arriving in their countries. Eventually PEN International formed a partnership with the expiring Parliament of Writers Cities of Asylum. In 2006 PEN became a founding member of ICORN—International Cities of Refuge Network. [More in future blog post]

The following year in 1995 the Peace Committee meeting in Bled featured a debate on hate speech, seen as both cause and effect in the conflicts. The gathering included such intellectual luminaries as Adam Michnik, an architect of Poland’s Solidarity movement and editor of the leading newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza in Warsaw. The debate was lively over the incendiary nature of hate speech and the limitations that should be imposed. Both in the Balkans War and in the civil war in Rwanda, which had just ended the year before, hate speech and writing fueled the strife. In spite of PEN’s advocacy for free expression, PEN also called on its members “to use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people” and pledge “to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds.” Even as “PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship,” it recognizes “freedom implies voluntary restraint” and members pledge “to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

The very Charter of PEN contained the axis of the debate. What were or should be limits on expression? Should PEN take a position? At the 1995 Peace Committee conference and in debates since, the views tended to fall according to cultural and national experience. Those in Europe, Africa and elsewhere who had experienced effects of hate speech urged stricter limitations on speech; whereas Americans, bred on the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, remained wary of limits and argued that the answer to offensive speech was more speech, the drowning out of harmful ideas with inspiring ones. In my notes of the meeting and debate that year, I find no consensus or clear recommendation except for a reminder from one speaker who knew and quoted Russian exile and dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: “Don’t go against your conscience and don’t tell lies!”

Proposal at 61st Congress for PEN to explore setting up an Exile Network. Resolution passed.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 15: Speaking Out: Life and Death