PEN Journey 2: The Fatwa

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments, though I’m not certain I can contain all these, but I hope this personal PEN journey may be of some interest.

It was President’s weekend in the US—between Lincoln and Washington’s birthday, coinciding with Valentine’s Day, 1989. I was President of PEN Center USA West and had just hired the Center’s first executive director ten days before. I’d been working hard with PEN and was also finishing a new novel, teaching and shepherding my 8 and 10-year old sons. For the first time in a year and a half my husband and I were going away for a long weekend without our children. He had also been working nonstop and had managed to clear his schedule.

On the plane to Colorado where we planned to ski, I read that Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses had been burned in Birmingham, England. The next day Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Rushdie. What was a fatwa? The Supreme Leader of Iran was calling for the murder of Rushdie wherever he was in the world, and he was offering a $6 million reward. As information about the fatwa developed, it also included a call for the death of whoever published The Satanic Verses.

I began making phone calls. This was a time before omnipresent cell phones so I had to find phones and numbers where people could reach me. (Usually our vacation dynamic was that my husband was on the phone.)

That first day I skied and wrote press releases on the ski lift and stopped at lodges on the mountain to use the pay phones to communicate with our new executive director. I’d ski another run then call the office again to answer questions from the press. What exactly was a fatwa, we were still asking? What did this mean for a writer? By the end of the day, I told my husband I had to return to LA.

“Can’t this wait?” he asked.

“No, it can’t,” I said.

Though a fatwa was a new concept, I understood, as did PEN members around the world, that a threshold had been crossed when a head of state issued a death warrant on a writer wherever he was in the world. Our two sons came out to be with my husband, and I returned to LA. Our board went into action as did PEN Centers around the globe to protest the fatwa. We organized a public event at the Los Angeles Times with writers and experts, an event which included readings from Rushdie’s book. Some were frightened by the threat, but most in PEN gathered. We contacted US government officials and began coordinating with global PEN centers, including American PEN in New York to confirm the support of writers for Rushdie and to protest Khomeini’s action.

Davis Dutton, center, of Dutton’s Books with some of his employees who voted to ignore the threats from Iran and stock “The Satanic Verses.”

Whatever the controversy over The Satanic Verses and its “insult” to Muslims, PEN was clear that the right of the writer to write without fear of death was primary.

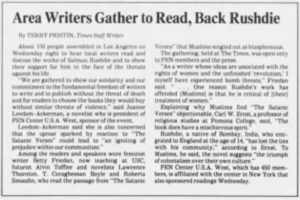

The mobilization included discussions with bookstores to encourage them to keep the book on the shelves for many were quietly removing it. The fuller scope of our PEN’s actions at the time is described in the column below in the PEN Center USA West’s newsletter and in a story in the Los Angeles Times.

Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1989

Next Installment: PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN Journey 1: Engagement

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. As Vice President Emeritus of PEN International and former International Secretary, former Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, former President of PEN Center USA West, board member and Vice President of PEN America and the PEN/Faulkner Foundation, I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down some of the memories. I will try in digestible portions to recount moments, though I’m not certain how easily I can contain all these. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of some interest.

February 13, 1989: I was President of PEN Center USA West and on an airplane when I read that Salman Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses was being burned in Birmingham. The next day a fatwa was issued on Rushdie. What was a fatwa, we all asked at the time, as we, along with PEN Centers around the world, mobilized to protest that a head of state was ordering the murder of a writer wherever he was in the world.

November 10, 1995: As Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, I was standing vigil with others outside the Nigerian Embassy in Washington, D.C. when word spread that novelist and activist Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

October 7, 2006: My phone rang at 7:30 on Saturday morning. I was International Secretary of PEN International, and the International Writers in Prison Program Director was calling to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya had just been shot and killed in Moscow. We all knew Anna—I’d last had coffee with her at an airport in Macedonia. We worked with her on the situation of writers in Russia and Chechnya and had enormous respect for her knowledge and courage.

January 19, 2007: We were about to begin a PEN International board meeting in Vienna when a call came from Istanbul. Hrant Dink had just been shot and killed outside his newspaper office in Istanbul. Dink was an editor of an Armenian paper and a writer whom members of PEN knew well and worked with on freedom of expression issues in Turkey.

Most writers long active in PEN’s freedom-to-write work can tell you where they were when the news broke on each of these cases. They can tell you because the lives of these writers and many others have been critical in the struggle for freedom of expression around the world.

In sharing memories of PEN, I begin with the writers and with the many friends around the globe who work on behalf of writers who don’t have the freedom to write without threat, imprisonment or death. As colleagues, we are bound together by the belief that truthful writing matters, be it journalism, fiction, poetry, drama, essays because stories and witnessing and creative imagination connect, inspire and shape us. Free expression is fundamental to a free society and is worth defending and expanding.

Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro Wiwa, Anna Politkovskaya, Hrant Dink

My own thirty plus years working with PEN began at a dinner meeting in Los Angeles in the early 1980’s. I was a young writer, new mother, former journalist who’d recently moved across the country from New York City where I taught writing at university and had friends and colleagues. I landed in the land of sun and Hollywood, and though I had a new college teaching job, I knew few people and even fewer writers. Like many who first seek out PEN, I came for the community.

My second meeting was at someone’s home where a presentation was made about writers in different parts of the world who were in prison because of their writing. I was introduced to PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. At that meeting, we wrote postcards urging the Chinese government to release Wei Jingsheng, a writer who was imprisoned for “counterrevolutionary” activities, particularly for his essay “The Fifth Modernization” which he’d posted on the Democracy Wall in Beijing in 1978. His manifesto argued that as China was modernizing with four principles of modernization, it needed to include a fifth modernization–Democracy.

As I learned about Wei Jingsheng and the other writers on whose behalf PEN worked, I became more active in the PEN Center on the West Coast of America called PEN Los Angeles Center. I was elected President in 1988. Shortly after the election, I attended my second PEN International Congress in Seoul, South Korea right before the Olympics there. (The first Congress I attended was in 1986 in New York City, where our Center’s members were registered with the foreign delegates. I was active at that New York Congress in the Women’s revolution and the statement that came from the Congress.)

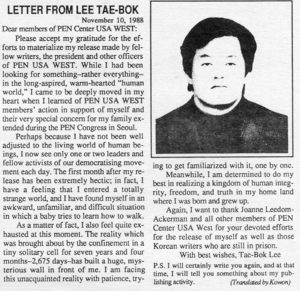

I arrived in Seoul late summer,1988 with our Center’s support for resolutions including one calling for the release of Wei Jingsheng and other writers in China, another resolution addressing writers in prison in South Korea, including our honorary member, publisher Lee Tae-Bok, and a resolution to change the name of PEN Los Angeles Center to PEN Center USA West. The name change had been passed by our center’s previous board but needed approval of the international Assembly of Delegates. It reflected our wider membership in the western part of the United States.

As president of PEN Los Angeles Center, I arrived as a young writer with a small delegation from Southern California, which included the former book editor of The Los Angeles Times and an English professor from UCLA. American PEN, based in New York, the largest of PEN’s more than 60 worldwide centers at the time was headed by Susan Sontag, president. American PEN didn’t want us to change our name and opposed our resolution on the floor of the Congress. While our two centers agreed on the other substantive issues of the Congress, including the problematic situation for writers in South Korea, and though we shared meals, the American PEN delegation, and Susan Sontag in particular, tried to get us to withdraw our name change, including a midnight call to me from Susan. The name change would be confusing, she said, and would take from the national scope of American PEN’s work. In that midnight call I listened to the arguments, then shared our thinking, which included the observation that our membership already came from many states west of the Mississippi, that in a country the size of the United States, PEN allowed more than one center, and for writers 3000 miles from New York, there was value in having more than one center of gravity. In the morning I presented American PEN’s arguments to my delegation, and we decided to go ahead and let our resolution go to the floor of the Assembly.

The representative from East Berlin noted: It would seem the East and West of America get along worse than the East and West of Germany. PEN Los Angeles Center’s resolution for a name change won by a wide margin, and we left the Congress as PEN Center USA West, which years later became PEN USA. I no longer live in Los Angeles but note that only in the past year –2018—did the members of the West Coast PEN decided to merge with PEN America in New York so there is now only one center of PEN in the US.

Most memorable and significant from the Seoul Congress was our delegation’s visit with the family of Lee Tae-Bok, our honorary member. “The house of Lee Tae-Bok’s parents is neat and spare, bedrooms with tatami mats on the floor, a living room with a sofa, a chair, a fish tank. There is no excess in the house, one senses out of choice. But there is an absence, not out of choice, for Lee Tae-Bok has been away in prison seven years. His mother worries that she will not see her oldest son out of prison before she dies,” I wrote in our Center’s newsletter. The family said that Lee Tae-Bok was in poor health and held in a cell four by five square meters, allowed out in the fresh air for only twenty minutes a day and wasn’t allowed to write except one letter a month to his family. His mother lamented the “hypocrisy” of the Korean government which had sentenced her son to life in prison because they said he published communist propaganda and yet they were greeting writers and “honored guests” at PEN’s Congress from Communist countries as well as inviting Eastern bloc athletes to Korea for the Olympic Games.

Digby Diehl and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman meet with the family of Lee Tae-Bok at the Lee home in Seoul in 1988.

In addition to our family visit, PEN Congress delegates petitioned the South Korean government on behalf of those in prison. A delegation from PEN International visited two of the writers in prison.

A few weeks after the Congress, notification reached us that Lee Tae-Bok had been released, though not everyone PEN spoke up for was released. I still remember where I was—I was in New York—when I heard the news, and I remember the elation. Many people worked on Lee Tae-Bok’s behalf so we couldn’t and didn’t take the credit, but we could feel some part of our actions, some push at the prison door helped spring it open. Release is not always the outcome for PEN’s work, but often it is. It is one of the goals. Over all my years in PEN, the release of a writer from prison still evokes a burst of hope and a measure of faith.

[Next installments: the watershed year 1988-1989 as the first global fatwa is issued against a writer, and writers and students in Tiananmen Square square off against China.]

Next Installment: PEN Journey 2: The Fatwa

Duck for a Day

I passed two ducks strolling down the highway on Easter morning—large mallards waddling and chatting with each other, staying on their side of the white-lined shoulder, yet precariously close to the cars whizzing by. They appeared oblivious to the traffic. I wondered where they were going and where they thought they were. They were several miles from water. On their side of the small highway on the Eastern shore of Maryland sprawled a shopping center with a supermarket, restaurants, movie theater. On the other side spread a bit of green field and beyond that more stores and beyond that woods, and beyond that the water—the Tred Avon River which eventually flows out into the Chesapeake Bay.

I was tempted to turn around and try to get a picture, but by the time I could make the turn and get back, they would likely have flown away. Instead, I carry their picture in my mind. I love ducks.

What kind of creature would you be if you were a creature? I would be a duck. Not a lion or giraffe or bear, not a gazelle or panther. No, I’d choose a duck. They can walk and swim and fly and are good at all three mobilities. They are modest, but much smarter and more ingenious than given credit. They have “a remarkable ability for abstract thought,” and “outperform supposedly ‘smarter’ animal species,” according to the Smithsonian. I am fairly certain walking down the highway, they were not debating the Mueller Report or the 2020 U.S. presidential elections, thus demonstrating already a more transcendent point of view.

I’d choose a mallard with the purple-blue wing feathers, the striking green set of feathers around the head (though that is only the male), stepping gingerly with big webbed feet, then gliding onto the water and when the mood strikes, lifting off the water into flight. I could live practically anywhere I wanted in North America, South America, Africa, Australia, Asia. I don’t have enemies except for humans who want to shoot me, and I have a pleasant disposition most of the time. I watch and listen, cooperate well with a group and have an uncanny sense of direction.

Readers, thank you for indulging this moment of fantasy in an effort to lift above the serious, yet endless and tendentious issues on the ground here in Washington.

What kind of creature would you be, at least for a day?

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

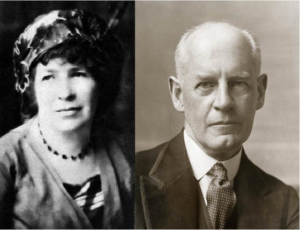

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

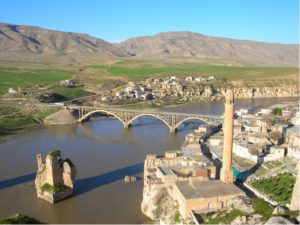

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference, March 2005

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through 141 centers in 99 countries. They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see this ancient city for himself, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together. –Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International

One More Voice

I thought about ending this blog. The final post: December, 2018—just over ten years, over 100 posts. Informal reflections on a decade. Since February, 2008 when I first attempted this new form and posted, the volume of blogs around the globe has proliferated to an immeasurable dimension. Today with blogs, podcasts, Facebook posts, LinkedIn, Twitter, photos on Instagram and other platforms and apps I don’t even know or use, everyone is talking about everything. My email box is filled with messages and information and notifications I never asked for, with political points of view I can barely consider, polls and surveys I never fill out…except one where I answer NO whenever it appears: “Should Hillary Clinton run for President?” NO. This answer doesn’t represent a political point of view so much as a measuring of time and tides…and consequences. It is time for others.

And yet rather than ending this blog, I write again. Perhaps a politician can’t help running for office.

What is one more blog post launched into the universe? The freedom to express is one I don’t take for granted when that freedom is shrinking around the globe and can have dire consequences in countries like China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Mexico, Venezuela. What is one more blog post launched into the universe? Just that, one more voice, a point of view no else exactly has.

Some writers I know have turned to photography. I understand the turn. Below are photos from a few days south, away from snow and ice storms, a brief visit to sun and the promise of spring. Comment, post yourself, confirm someone is receiving. Happy winter’s end or summer’s end, depending in which hemisphere you live.

Pause…Watch…Listen…See…Hear

As we slide into the holidays and sweep towards the new year, events are in a swirl and spiraling mostly downwards it would appear, at least in Washington, DC where I live.

Photo Credit: Julia Malone

Stop! A voice insists in my head.

Pause. Watch. Listen.

Turn off the car radio, the tv news, the commentators, the politicians, at least for a moment.

Go to the park. Or to the country. Allow space to receive other thoughts.

Hear the wind rustling through a green bush at the edge of the parking lot.

See the wind knocking off the last leaves of a tree.

Watch the flag, still at half mast, saluting the wind.

Remember the three-year-old on stage last night at the community theater, trying to keep up and match steps with the older children.

Enjoy the three dogs—black, blonde and brown retrievers—running across the open field.

Hear the carols: “Sleigh bells ringing…Lovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you…”

No sleighs in Washington, but the carols ring out, and traditions wrap around in old words and sentiments even as new words—”border wall, shutdown, impeachment, resignation, fraud, lies”—fill the public discourse.

Time to get out of town?

Or just time to pause, watch, listen and try to see and hear other harmonies.

Giddy up! Giddy up! Let’s go. Looking for the Wonderland of Snow!

Happy holidays to All!

Journey of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving—a favorite American holiday that includes everyone—reminds us to take time to give gratitude and to give. Though Thanksgiving has come and gone, the base of gratitude and the reminder to give in whatever way and fashion builds a foundation that endures and can outlast political, social and even climatic turmoil.

In this space and in this holiday season, I hope readers will share stories and thoughts on this theme. Gratitude and giving are the beginning and end of a redemptive journey.

London: Autumn Respite Around the Pond

A few years ago I penned a blog “Sounds of Summer” where I listened to the sounds of a summer afternoon. I let the politics and opinions and controversies of Washington, where I live, recede in my mind on the threshold of presidential elections, and I focused on the moments of nature and the wonders of a child’s summer world. I find myself wanting to retreat there more and more these days as the civic dialogue and political events seem harsher and less civil and downright mean.

In the last month I’ve had reason to travel to Beirut and London, where I considered events from a slightly different point of view, though no less fraught. The constant news coverage and the acrimony of the Kavanaugh Supreme Court hearings in the U.S. was replaced by the general uncertainty over refugees and the government in Beirut and by the angst over Brexit in London. While in Beirut, the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi broke in the news, and the horror of the unfolding tale of death and torture riveted attention in Washington and London as well. The possible political coverup currently brewing for this brutal violation of human rights remains the most troubling of all.

And yet for a moment—just an hour—in London yesterday I sat around the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens and allowed myself time to listen to the sounds and to witness life without a wider prism of consciousness and a larger world intruding.

On the crisp October morning the leaves stirred, still dusky green on the trees, not yet the vibrant reds and yellows of fall. Autumn arrived gently here in slight gusts of wind. A robust population of birds—elegant white long-necked swans, husky geese, green-faced mallards, plain brown ducks and a bevy of smaller birds cruised the water, circling the pond, eventually veering towards the edges where passersby tossed bread crumbs and seeds. A troupe of white seagulls swooped in for a landing on the water like trained hydroplaners and then just as abruptly and deftly took off for other parts of London.

At the far end of the pond sat Kensington Palace, quiet that day, home to the Duke and Duchess of Sussex—Prince Harry and his American bride Meghan Markle—who at the moment were in Australia, where they announced they’re having a baby.

People of all backgrounds circled the pond, dressed in slacks, jeans, dresses, light jackets, in hejabs and thwabs, children in strollers, young and old, sitting on the benches that ring the pond. School children in florescent green and yellow vests jogged by on a morning run.

Two elderly ladies and I increased our walking pace in a silent, unannounced race to the one empty bench at the bottom of the pond. I won, but they sat down beside me anyway, and we shared this coveted space where they talked quietly, and I wrote, and we watched this slice of morning.

A tiny dog trotted by as two stragglers panted past trying to catch up with their schoolmates. A couple stopped beside us and talked loudly on the phone in a language I didn’t recognize. In front of us a swan groomed herself, shaking off the water.

The grim headlines in the news: the possible failure of Brexit, the assassination and dismemberment of Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate, the US government’s closing of borders to a new convoy of migrants, the slippery commitment to truth for a moment receded on a blue sky London morning on the edge of autumn before the days grew short and dark.

A teacher with his final two lagging students jogged past, shouting, “Come on, guys…Let’s sprint to the finish! You can do this!”

Reluctantly I rose from the bench and left my fellow sojourners as I headed into the city for meetings and the work of the day.

Peace: Fabric with a Million Threads

Earlier this summer I had the opportunity to moderate a panel of high school teachers at the United States Institute of Peace called “A Year in the Life of a Peace Teacher.”

United States Institute of Peace in Washington, DC

On that morning of July 10 two positive news events broke: the final young soccer players and their coach, who had been trapped for almost two weeks, made it out of the caves in Thailand. And Liu Xia, wife of Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese Nobel Peace Laureate who died last year in custody, landed in Europe, released after a decade of virtual house arrest in China.

For me these events connected to the panel on the teaching of peace-building.

Was peace possible? Could peace be “built”? The answer we concluded that morning with cautious optimism was: Yes.

The miraculous rescue of the soccer team resulted because highly skilled citizens from nations around the world, including the U.S., Australia, Denmark, Britain, China and most importantly Thailand came together and exerted their best efforts with a common goal everyone agreed on.

Freedom for Liu Xia resulted in large part because citizens and politicians around the world spoke up and advocated on her behalf though a similar effort had not won the release of her husband.

That morning, listening to the teachers and their work with students reinforced a view that peace was not just building bridges between two opposing pylons or signing treaties, but was the weaving of hundreds, thousands, millions of threads, of each citizen taking responsibility within his/her own community.

Each year the U.S. Institute of Peace, founded in 1984 as a nonpartisan Institute to promote peace and resolution of conflicts around the world, also focuses on the U.S. and selects four high school teachers for year-long training which they take into their classrooms. They work on problem-solving and peace-building in their communities and also study global peace opportunities.

This year’s teachers from Missouri, Montana, Florida and Oklahoma shared ways they and their students ignited discussion in their classrooms and in their communities and then took initiatives relating to issues of race, immigration, etc. They emphasized the understanding that peace didn’t mean avoiding conflict but rather finding ways to engage nonviolently and then to find ways to resolve conflicts by listening, determining the interests of the other, showing empathy.

Specific stories of the teachers and their journeys with their students can be heard on this link.

To conclude the panel it was appropriate to quote Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo. In his career and in his final statement to the court before he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for his writing and work towards democracy, he told the judge: “I have no enemies and no hatred.” In his life Liu explained that to build a society without hate, one had to begin with one’s self. After he died in custody last year, many questioned whether he would have claimed this had he known his end, but those who knew him well said he would have because he believed the responsibility for a peaceful and fair society began with oneself.

Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people… It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, it can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.

It was poignant and fitting that day to see Liu Xiaobo’s wife Liu Xia’s smile as she landed in Helsinki.

Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression

(Below is my talk for the Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression, a conference held every two years, but this year it is being held via video May 26-27. For the first time in 21 years the organizers judged that a gathering in person was too problematic given the arrests and crackdowns on the media. Turkish presidential elections are scheduled for June 24 alongside parliamentary elections.)

I first visited Turkey for the inaugural “Gathering in Istanbul” in March, 1997. At the time I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee and joined 21 other writers from around the world. Along with over a thousand Turkish artists and writers, most of us had signed on to be “publishers” for Freedom of Thought, a book that re-issued writings which had violated Turkey’s laws against “insulting the State.” The book included work by noted authors, including celebrated novelist Yasar Kemal. None of us aspired to go to Turkish prison, but we understood the importance of showing up and showing solidarity with our Turkish colleagues. During that Gathering we visited prisons where writers and publishers were incarcerated and visited court rooms where they were charged.

Inaugural “Gathering in Istanbul” March 1997

In the subsequent decade, conditions for writers in Turkey improved. An amnesty released writers from prison; oppressive legislation was rescinded though new laws replaced old articles in the penal code. But the climate opened. We all took hope that Turkey might signal an opening of consciousness and an easing of political and legal constraints globally.

Unfortunately, that opening has closed, and we are here today on video because the biennial ‘Gathering in Istanbul’ for the first time in 21 years is too problematic to hold in Istanbul. The situation for freedom of expression is worse than ever in Turkey with more writers in prison than anywhere else in the world. Depending on the statistics of the day, there are more than 250 journalists and media workers in or facing prison terms, 200 media outlets closed, and thousands of academics and civil servants let go or facing charges.

Yet we are here, even if on video. And the organizers remain steadfast in Turkey. I take heart in the commitment of individuals who understand that freedom of expression is central to a free society and work towards that end.

For this “Gathering in Istanbul” it was suggested we look at “Freedom of Expression Around the World,” not just in Turkey. My general observation is that the world is reversing direction from those days 20 years ago when many thought authoritarianism was yielding globally to democracy and freedom.

The situation in my own country, the United States., is as fraught as it has ever been in my lifetime in the relationship between the government and the media, but the press is protected by the U.S. Constitution, laws, history and society. The majority of U.S. citizens still remain committed to protect freedom of expression and to remain vigilant though sometimes I fear we are preoccupied with our own challenges to the exclusion of more dire challenges to free expression around the world. I also fear we have lost credibility and impact when speaking out on these issues. Yet as an American, I can hold vigils in front of prisons, sit in courtrooms, write articles and books, meet Ministers, and then return home. I’m able to write and to speak out without being threatened with imprisonment or death.

I’d like to focus the rest of my talk on the courageous writers in the Democracy Movement in China, especially after the death of Liu Xiaobo, Nobel Peace laureate who died last July in prison after serving nine years of an eleven-year sentence for “inciting subversion of state power” because of his participation in the drafting and circulating of Charter 08. I have the privilege of being an editor for the English-language edition of The Memorial Collection of Liu Xiaobo. The collection includes writings from dozens of Liu’s colleagues inside and outside China, who knew him and pay tribute to the man, his ideas and to the consequential voice he had in articulating and taking action on behalf of a free society.

One of the authors of Charter ’08, a document signed by hundreds of Chinese writers, intellectuals and citizens, Liu Xiaobo and others set out a democratic vision and path for China, using rule of law and consensus, not weapons and violence. It is individuals like Liu Xiaobo and his fellow Chinese writers and thinkers, who one hopes will eventually prevail. Like the writers and thinkers in Turkey, they are committed to ideas, to the rule of just laws and to nonviolent means to bring about change and wrest society from tyrannical modes.

Liu Xiaobo understood that a free society begins with the individual consciousness. In his Final Statement “I Have No Enemies” he addressed the court:

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people. It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to progress of our country to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

Such sentiment was difficult for many to accept, especially after he died. Many questioned whether he would have expressed the same sentiments had he known his end. I’ve been assured by those who knew him well that he would have stood by this statement. His commitment was rooted in his view of himself and of what it would take to change society.

A longtime colleague Cui Weiping has observed that Liu Xiaobo “…viewed the world through boundaries of his own making. Whatever he wouldn’t allow into his life, he was also unwilling to allow into the world. For instance, if he didn’t have violent tendencies in his own life, he would not let the behavior of others impose on him. If he valued freedom and autonomy, he would not become mired in hatred because of the crimes of others, since hateful people were dominated by the other side. If he experienced the good things and positive feelings of human life, he knew all the more that he must allow what was good and open to take root in himself and not what was biased and narrow-minded. His life was oriented toward love and light, not toward hatred and darkness. This was his own decision and what he was willing to take upon himself; every person writes his own history. Other people could choose to go along with Xiaobo or advance alongside of him, but there was no need to feel that this was his error or flaw that must be corrected or surmounted. Twenty years passed like a day, and he was a trailblazer for people who insisted on their own ideas. China lacks trailblazers like Xiaobo, and that is what allowed him to become a standard-bearer for the Chinese Democracy Movement and gain the widespread endorsement of the international community.”

A small number of Chinese writers drafted Charter 08, thousands of citizens have signed it, but only one went to prison and died.

No one knows and few can predict the success of Charter 08’s vision and the ultimate impact of Liu Xiaobo, but history has a long arc and may well bend to those who see our common humanity and the universal value of freedom for the individual. By focusing on the individual’s responsibility for his own behavior and consciousness, Liu offered the tools to empower all, for no government has the mandate over one’s individual consciousness. There the individual sets his or her own terms of engagement with the world.

In reading the essays of the many Chinese writers who knew and admired Liu Xiaobo and his vision, I also think of Turkish writers and artists I have had the privilege to know over the years who continue to work towards a free society.

The two countries and circumstances are different, and many would say Turkey is not as extreme as China, but in all the years I have been working with PEN, it was Turkey and China which placed the most writers under pressure. In China the sentences were often longer and harsher, but the numbers were greater in Turkey. But in both nations the individual voices of writers, publishers and artists continue to inspire.