Posts Tagged ‘Liu Xia’

Nobel Peace Prize for Liu Xiaobo Ten Years After

PEN International marks the ten-year anniversary of the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to writer, literary critic and human rights activist Liu Xiaobo on 10 December 2010. PEN’s Liu Xiaobo Anniversary Campaign acts as a commemoration of Liu Xiaobo’s life, his contribution to Chinese literature, and his selfless work promoting basic freedoms in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The campaign also highlights the cases of writers Gui Minhai, Kunchok Tsephel, Yang Hengjun and Qin Yongmin who are currently detained by the PRC government. The campaign seeks to raises awareness of their situation, to boost advocacy work on their behalf and to ensure that they and their families feel supported and not forgotten.

The following links to PEN’s campaign. Below is text and Chinese translation of my video tribute to Liu:

Hello, I’m Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Vice President Emeritus of PEN International.

您好!我是乔安尼•利多姆-阿克曼,国际笔会荣休副会长。

Ten years ago, essayist, poet, activist and PEN member Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace. Liu envisioned and worked towards a peaceful and democratic pathway for China. Beginning with the protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and through the subsequent decades, he spoke out and wrote and gathered people and ideas in support of a China where individual freedom was valued and protected.

十年前,散文家、诗人、活动家、笔会成员刘晓波成为首位荣获诺贝尔和平奖的中国公民。刘先生设想并致力于中国走向和平民主的道路。他从1989年天安门广场抗议运动开始,在随后数十年言说和书写,并聚集民众及理念,以支持一个重视和保护个人自由的中国。

In 2008, he and others drafted Charter 08, which set out this democratic vision. He and others gathered hundreds and then thousands of signatures from Chinese citizens who endorsed the vision. Charter 08 did not call for an overthrow of the government so much as a transformation of the way government related to its citizens in a transition to a democratic society that would include freedom of expression and assembly.

2008年,他和其他人起草了《 零八宪章》,阐明这一民主愿景。他们从支持这一愿景的中国公民那里汇集了成百上千人签名。 《零八宪章》并未呼吁推翻政府,而是要转变政府相对于公民的方式,转型为包括言论自由和集会自由的民主社会。

Liu Xiaobo has been called the Nelson Mandela or Václav Havel of China because of his ideas, his activism and his leadership. Like Havel, Liu was committed to nonviolent action as a means of achieving change, and he was an inspired writer.

刘晓波因其理念、言行和领导能力而被称为中国的曼德拉或哈维尔。像哈维尔一样,刘晓波也致力于以非暴力行动来实现变革,他是一位受鼓舞的作家。

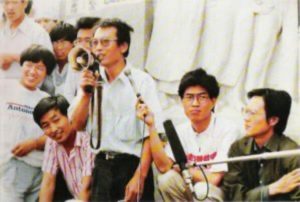

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

I first encountered Liu Xiaobo through PEN. After the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989, PEN worked on behalf of the writers who had been arrested in the protest, including Liu Xiaobo. Liu had also been instrumental in persuading students to leave the Square before the soldiers and tanks rolled in to attack and possibly kill them. At the time of Tiananmen Square, I was President of PEN Center USA West. A few years later when Liu was again imprisoned for his writing, I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee.

我首先通过笔会遭遇刘晓波。在1989年天安门广场镇压后,笔会致力于代表在抗议活动中被捕的作家,包括刘晓波。刘晓波还曾劝说学生离开广场,以免士兵和坦克席卷攻入广场可能杀死他们。在天安门广场抗议时,我担任美国西部笔会会会长。几年后,当刘晓波再次因写作而被监禁时,我是国际笔会狱中作家委员会主席。

Liu Xiaobo then went on to become one of the founders and the second President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), whose members lived inside and outside of China. He was instrumental in establishing the platforms by which these writers could communicate and share ideas about a society where freedom of expression and democratic processes could exist.

刘晓波随后成为独立中文笔会(ICPC)的创始人之一和第二任会长,该笔会成员居住在中国境内和海外。他发挥作用建立起这个平台,这些作家们可以借此平台,交流和分享有关这样一个社会的理念,在那里言论自由和民主进程得以存在。

During the time Liu was President of ICPC, I was the International Secretary of PEN. However, Liu was not allowed out of mainland China into Hong Kong where ICPC had its meetings, and I didn’t get to the mainland until in 2010 after he was arrested for the fourth and final time, so we never met in person, though over decades I have worked with many of his colleagues.

在刘晓波担任独立中文笔会会长期间,我曾担任国际笔会秘书长。然而,他没获准离开中国大陆前往独立中文笔会举行会议的香港,而直到他 第四次也是最后一次被捕后的2010年,我才去中国大陆,因此我们从未亲身见面,尽管数十年来我一直与他的许多同事共同工作。

Liu Xiaobo was the writer the Chinese government feared the most and therefore arrested. Liu was charged as “an enemy of the state” for “incitement of subverting state power” because of his ideas, his writing and his participation in the drafting and circulating of Charter 08. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison. He was the only recipient of the Nobel Prize who was in prison at the time and not allowed to attend the ceremony. Only an empty chair represented him. His wife Liu Xia was also not allowed to attend. Liu Xiaobo died in custody July 13, 2017.

刘晓波是中国政府最害怕的作家,因此而被捕。由于其理念、写作并参与起草和传播《 零八宪章》,刘晓波被指控为“煽动颠覆国家政权”的“国家敌人”。他被判处了十一年徒刑。他是当时在监狱中而未被允许参加颁奖典礼的唯一诺贝尔奖得主,只有一把空椅子代表他。他的妻子刘霞也被禁止出席。刘晓波于2017年7月13日去世。

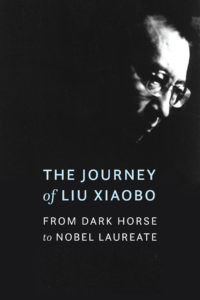

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

他去世后,全世界了解他的作家开始书写他及其作品,书写中国以及自由主义和民主理想之路。今年出版了《刘晓波之旅程:从黑马到诺奖得主》(文文版),包含75篇以上的文章,可能是来自中国民主活动人士的最大笔墨聚会,既是对刘晓波的回忆致敬,也是对中国民主运动的研究。

China’s Democracy Movement and Liu Xiaobo’s legacy still inspire those inside and outside of China, from the mainland to Xinjiang to Tibet to Hong Kong and to neighboring countries engaged in the struggle for political reform and an end to authoritarian rule.

中国民主运动和刘晓波的遗产,仍然激励着中国内外的人们,从大陆到新疆,到西藏,再到香港,再到争取政治改革和结束专制统治的邻国。

Some have said that because of China’s ascendency in the last decade, the legacy of Liu Xiaobo has been reduced to nothing. But a longer view of history shows that the same was said of those visionaries and martyrs for free societies in Eastern Europe and South Africa.

有人说,由于近十年来的中国崛起,刘晓波的遗产被削减为零。然而,更长的历史证明,同样的说法也曾针对过那些在东欧和南非争取自由社会的远见者和烈士们。

Societies move forward and are changed by ideas, by leaders, and ultimately by their citizens. Liu Xiaobo did not aspire to personal power, but those in power came to fear him because he understood how to move ideas into action.

社会向前发展,并通过理念、领导者及最终通过其公民而改变。刘晓波并不渴望个人权力,但是当权者却开始害怕他,正因为他知道如何将理念付诸行动。

As individuals one by one—be they writers, lawyers, academics or others—are put into prison and taken out of the discourse, those in power attempt to maintain their control. That is why it is important to keep an eye not only on the monolith of regimes and government, but to protect the individuals who hold the powerful to account.

当作家、律师、学者或其他人一个接一个地被关进监狱并从话语中带走时,当权者试图维持其控制。这就是为什么重要的不仅是着眼于政权的垄断和政府问题,而且要保护那些向当权者追责的个人。

Liu Xiaobo declared, “Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth.”

刘晓波声言:“表达自由,人权之基,人性之本,真理之母。”

Liu Xiaobo insisted that to transition to a state that one wanted to live in, one needed to have citizens who represented those values even in the struggle.

刘晓波坚持认为,要过渡到一个人们想要生活的国度,就需要有即使在斗争中也代表那些价值观的公民。

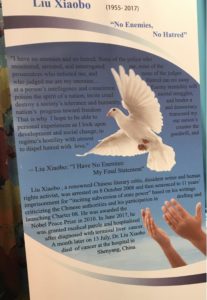

I’d like to read from his Final Statement to the judge who sentenced him: “…now I have been once again shoved into the dock by the enemy mentality of the regime. But I still want to say to this regime, which is depriving me of my freedom, that I stand by the convictions…I have no enemies and no hatred…Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience. Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress toward freedom and democracy. That is why I hope to be able to transcend my personal experiences as I look upon our nation’s development and social change, to counter the regime’s hostility with utmost goodwill and to dispel hatred with love.”

我要朗读他的《我的最后陈述》,是他写给判决他的法官的:“……现在又再次被政权的敌人意识推上了被告席,但我仍然要对这个剥夺我自由的政权说,我坚守着……信念——我没有敌人,也没有仇恨。……仇恨会腐蚀一个人的智慧和良知,敌人意识将毒化一个民族的精神,煽动起你死我活的残酷斗争,毁掉一个社会的宽容和人性,阻碍一个国家走向自由民主的进程。所以,我希望自己能够超越个人的遭遇来看待国家的发展和社会的变化,以最大的善意对待政权的敌意,以爱化解恨。”

After Liu Xiaobo’s death, a colleague who had known and worked with him for decades was asked if he thought Xiaobo would have changed his statement had he known his end. His friend said No, that his final statement and sentiment that “I have no enemies, no hatred” was at the heart of who Liu Xiaobo was.

刘晓波去世后,一位与他认识并合作了数十年的同道被问到,如果刘晓波知道自己的结局,他是否认为晓波会改变自己的陈述。他的朋友说“不会”,因为“我没有敌人,也没有仇恨”的最后陈述和观点,正是刘晓波其人的核心。

Now Liu Xiaobo’s beloved wife Liu Xia, who is herself a poet, will read one of his poems written to her: “Van Gogh and You” addressed to “Little Xia”:

现在,刘晓波的挚爱妻子,自己也是诗人的刘霞,将朗诵他写给她的一首诗:《梵高与你——给小霞》:

Peace: Fabric with a Million Threads

Earlier this summer I had the opportunity to moderate a panel of high school teachers at the United States Institute of Peace called “A Year in the Life of a Peace Teacher.”

United States Institute of Peace in Washington, DC

On that morning of July 10 two positive news events broke: the final young soccer players and their coach, who had been trapped for almost two weeks, made it out of the caves in Thailand. And Liu Xia, wife of Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese Nobel Peace Laureate who died last year in custody, landed in Europe, released after a decade of virtual house arrest in China.

For me these events connected to the panel on the teaching of peace-building.

Was peace possible? Could peace be “built”? The answer we concluded that morning with cautious optimism was: Yes.

The miraculous rescue of the soccer team resulted because highly skilled citizens from nations around the world, including the U.S., Australia, Denmark, Britain, China and most importantly Thailand came together and exerted their best efforts with a common goal everyone agreed on.

Freedom for Liu Xia resulted in large part because citizens and politicians around the world spoke up and advocated on her behalf though a similar effort had not won the release of her husband.

That morning, listening to the teachers and their work with students reinforced a view that peace was not just building bridges between two opposing pylons or signing treaties, but was the weaving of hundreds, thousands, millions of threads, of each citizen taking responsibility within his/her own community.

Each year the U.S. Institute of Peace, founded in 1984 as a nonpartisan Institute to promote peace and resolution of conflicts around the world, also focuses on the U.S. and selects four high school teachers for year-long training which they take into their classrooms. They work on problem-solving and peace-building in their communities and also study global peace opportunities.

This year’s teachers from Missouri, Montana, Florida and Oklahoma shared ways they and their students ignited discussion in their classrooms and in their communities and then took initiatives relating to issues of race, immigration, etc. They emphasized the understanding that peace didn’t mean avoiding conflict but rather finding ways to engage nonviolently and then to find ways to resolve conflicts by listening, determining the interests of the other, showing empathy.

Specific stories of the teachers and their journeys with their students can be heard on this link.

To conclude the panel it was appropriate to quote Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo. In his career and in his final statement to the court before he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for his writing and work towards democracy, he told the judge: “I have no enemies and no hatred.” In his life Liu explained that to build a society without hate, one had to begin with one’s self. After he died in custody last year, many questioned whether he would have claimed this had he known his end, but those who knew him well said he would have because he believed the responsibility for a peaceful and fair society began with oneself.

Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people… It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, it can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.

It was poignant and fitting that day to see Liu Xiaobo’s wife Liu Xia’s smile as she landed in Helsinki.

“Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred”

The train from Copenhagen airport to Malmö, Sweden took just half an hour across the 21st century Øresund Bridge, which spans five miles of water, then the train dove into 2.5 miles of tunnel. Looking out the window at farmland and the blue waters of the Baltic Sea, I imagined this journey was not so easy 74 years ago with Nazis in pursuit. In 1943 as the Nazis went to sweep Denmark’s 7800 Jews into concentration camps, Danish and Swedish citizens rallied, and 7220 people managed to escape in boats across this Sound to nearby Sweden. Thousands landed in Malmö where I was headed for a less dramatic, but still fraught, occasion.

Members of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) whose writers live inside and outside mainland China were joining writers from Uyghur PEN, Tibetan PEN and members from Inner Mongolia, along with writers from PEN Turkey and Azerbaijan for the First International Conference of Four-PEN Platform: “Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred.” Swedish PEN was providing the safe space for debate, discussion and strategies of action on human rights and freedom of expression. Just six weeks before, one of ICPC’s founding members and honorary President Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo, died in a Chinese prison after serving nine years of an 11-year sentence for drafting Charter 08, a document co-signed by 308 writers and intellectuals calling for a more democratic and free China.

A recognized leader in China’s Democracy Movement, Liu Xiaobo’s loss was deeply felt. A number of the writers gathered knew and worked with Liu. Most knew at least one fellow writer in prison. Many now live in exile themselves. Almost half of PEN International’s writers-in-prison cases are located in the regions represented at the conference.

The theme “No Enemies, No Hatred”—drawn from Liu Xiaobo’s final statement at his trial—sparked the debate in Malmö.

Keynote speaker Nobel Laureate Shirin Ebadi challenged, “But I do have enemies and I do feel hatred.” Facing death threats from her government in Iran, she had to leave everything behind at age 63 and move to London.

“Liu Xiaobo said he had no hatred and no enemies, but he also never compromised with any dictators,” she noted. “We must fight against dictators but our weapons are our pens and are nonviolent. We must not be silent. We can’t compromise with governments such as China who would eradicate an ‘empty chair’ from the internet.” [When Liu Xiaobo was unable to attend the Nobel ceremony because he was in prison, the Nobel Committee placed an empty chair on stage to represent him. The Chinese government is said to have censored the term “empty chair” from the internet in China.]

“What is the use of a pen if Liu Xiaobo is dead?” challenged one writer. Another speculated that if Liu Xiaobo had known how his life would end, he would have changed his message. A friend of Liu’s assured that he would not because for him no enemies and no hatred was a spiritual commitment.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows),” Liu declared to the court at his trial. “It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy…. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate…. No force can block the thirst for freedom that lies within human nature, and some day China, too, will be a nation of laws where human rights are paramount.”

Within this frame and this hope, stories of persecution were exchanged among the Tibetan, Uyghur and Mongolian writers in China and among writers from Azerbaijan and Turkey, where over 150 writers and journalists are currently in prison and over 100,000 judges, academics and civil servants have been fired.

Uyghur and Mongolian writers noted that starting September 1 the Uyghur language is banned from all schools.

“The Chinese call all Uyghurs terrorists,” said one participant. “I have never seen a gun or a bomb in my life, but my name is on Interpol’s list because of my pen. I am a German citizen, and I was in Italy, invited by the Italian Senate when Italian police arrested me because the Chinese government put me on a terrorist list because I speak out for the Uyghurs.”

Can one operate against totalitarian, oppressive governments without hatred and enemies? The question remained unresolved, but participants agreed that protest and actions needed to remain nonviolent. To amplify the voices of the writers who were in prison, those outside could publish them, protest to their governments and recognize the writers with awards. Implicit was a belief in the power of culture and ideas to ultimately change society.

The 2016 Liu Xiaobo Courage to Write Award was given at the conference to Hu Shigen and Mahvash Sabet. Writer and lecturer Hu Shigen spent his career in the Democracy Movement since 1989 Tiananmen Square when he was arrested for “counterrevolutionary propaganda” and sentenced to 20 years in prison and after release was arrested again for “subverting state power” and returned for seven and a half years in prison where he still resides. Mahvash Sabet, a teacher and noted Baha’i poet, was detained for her faith and for “acting against the security of the country and corruption on earth” in Iran and is now serving a 20-year sentence in Evin prison in Tehran. Her friend Shirin Ebadi accepted the award on her behalf.

Other cases highlighted by the conference included Ilham Tohti, Nurmuhemmet Yasin, Gulmire Imin, Memetjan Abdulla, Gheyret Niyaz, Zhao Haitong, Omerjan Hasan, Qin Yongmin, Zhang Haitao, and Mehman Aliyev. The gathering also highlighted the situation of Liu Xia, Liu Xiaobo’s wife, who is believed still under house arrest. Many are working in the hope of getting her out of China.

When Shirin Ebadi was presented a statue of Liu Xiaobo, she noted that it would sit beside a statue she’d been given of Martin Luther King.

Dr. King’s writing of 54 years ago in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” read at the closing demonstrated the power of ideas and words to endure long after their author has passed away: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Two Voices Behind the Iron Doors

(In the past weeks I was brought to focus again on the situation of two writers in prison, one in China, the other in Turkey, both countries that have consistently challenged and imprisoned writers. In China the hope for expanded freedom of expression that came with the Olympics and China’s engagement with global institutions has not materialized, and Chinese writers remain in prison with long sentences. The situation in Turkey for a while was improving, but in the past year arrests have again escalated.)

Voice in China

I had dinner recently with three colleagues of Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel laureate and writer currently serving an 11-year sentence in a Chinese jail. Two of his friends, Shen Tong and the other friend arrived in the U.S. around the time of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, but the younger best-selling writer and democracy activist Yu Jie didn’t leave China until January, 2012 after being detained and tortured and put under house arrest. He now lives in Virginia.

Yu Jie consulted with Liu Xiaobo during the writing of Charter 08, the manifesto calling for democracy in China which resulted in the imprisonment of Dr. Liu. He and Liu Xiaobo also co founded the Independent Chinese PEN Center, and Yu Jie has written a biography of Liu Xiaobo.

At a round wooden table in a bustling Washington restaurant the friends outlined their campaign. Among their strategies, they are working to gather a million signatures worldwide calling for the release of Liu Xiaobo and his wife Liu Xia, who has been under house arrest since Liu’s imprisonment. So far they have gathered about half a million signatures in 130 countries, including from 135 Nobel Laureates. The Friends of Liu Xiaobo are also campaigning for the release of other prisoners of conscience in China. They and the Nobel Laureates are mobilizing support around the world and have been told the Chinese government has started to take notice and to worry about the scope of the campaign. Dr. Liu is the only Nobel Peace Prize Laureate in prison.

Here is the link to sign the petition.

* Friends of Liu Xiaobo Twitter: http://twitter.com/lxbfree,

* Facebook page: http://www.facebook.com/Free.Liu?fref=ts

Poem by Liu Xiaobo:

A Small Rat in Prison

a small rat passes through the iron bars

paces back and forth on the window ledge

the peeling walls are watching him

the blood-filled mosquitoes are watching him

he even draws the moon from the sky, silver

shadow casts down

beauty, as if in flight

a very gentryman the rat tonight

doesn’t eat nor drink nor grind his teeth

as he stares with his sly bright eyes

strolling in the moonlight

5. 26. 1999

Translated by Jeffrey Yang

Voice in Turkey

I reached into the drawer of my post box in Washington this week and pulled out a card addressed to Doame Leexa-Acker (the name no doubt a reflection of my poor penmanship on the receiving end.) The envelope was from Turkey, and the postcard inside had a picture of Diyarbakir, the ancient city in southeastern Turkey that is the capital of the Kurdish region and the hub of fighting for decades between the Army and the PKK.

In a neatly printed hand the card read:

21 March Newroz Kurdish religiots [sic[ celebrate.

1200 day not free. I’m healt [sic] bad.

I’m free about concerned. I need you children.

I at the house must be. I’ not killer!

I’m writer, lawyer, peacemaker.

I’ hope back you can be. Please.

Grand peace in the door.

Thank you for post cards 🙂

Best wishes,

Muharrem Erbey

Even with the challenge of English, the appeal resonated. I looked up his case and reminded myself of his situation: Muharrem Erbey is a writer and a human rights lawyer, Vice President of the Human Rights Association. He was imprisoned under the Anti-terror Law in 2009. According to PEN International, he has compiled reports on disappearances and extra-judicial killings in the Kurdish region and has represented individuals in the provincial, national and international courts, including the European Court of Human Rights. He was one of dozens of writers and journalists tried under the auspices of the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) trials which targeted pro-Kurdish writers, publishers, academics and translators, tried together as KCK’s “Press Wing.” He has published articles and co-edited a collection of Turkish and Kurdish language stories. His own short story collection, My Father, Aharon Usta was delayed for publication after his arrest.

Last fall Erbey wrote to those at PEN who had advocated on his behalf: “I send you my heart’s warmth from behind the iron doors and bars and damp, cold, wet walls of prison….My speeches and comments never contained words of violence.”

Circulating a writers’ work and giving voice to those silenced is part of what writers can do for each other. Below is a section of a translated letter from Erbey describing the seasons in prison with a link to the full letter:

I want to tell you how I have experienced the four seasons from behind bars.

Autumn. In the morning, as I reach over the barbed wire crowning this wall six or seven metres in height, the sun as it passes briefly through our ventilation system and away again, the sound of the sparrows that perch on the wire and fly off with the crumbs of bread we toss, the squawking of doves overhead, this sky stained a cold and faded blue, the wind that howls and carries dry fragments of grass through the ventilation – all work the ache of loneliness finely and deeply into me, as the captivity of my shivering body grows a storey higher. I am listening to the sound of the wind. The chattering of clothespegs hanging from the line, the clatter of water bottles roaming the area, flying newspaper scraps and silently wandering dreams, hopes that grow from a whisper to a roar – they strike the wall and go no further.

Winter. There is a weak sun that does not warm you. The air is cold. This place is alien to life, with its endless concrete and iron, these wire fences. The walls’ peeling grey paint, their damp, drains you of energy. Your dreams are caked in dust and soot. At 6 am, as we four men in each room wake to the metallic clank of iron doors, we wish that this were all a dream, but it is not; everything is real. As it happens, prison is the one place one would never want to be when waking. We have this privilege. The prison walls allow everything to pass, except time. I am freezing, my throat dries up, my eyes are burning, there is the weight of tonnes on top of me; it is as if I am tied in steel cord. I cough and I sneeze. In winter prison becomes a prison, and the cold season seems to go on forever. At night we go to the toilet dozens of times.

Spring. Taking root in a crack of broken concrete, seeds brought over the walls and wire by the wind display nature’s irresistible force with the unfurling of their leaves. At first glance you think that the seedling has broken its way out through the concrete. But nature stubbornly allows life to take hold, splitting concrete despite every restriction. An unimaginable aroma of oleaster surrounds us. You know that spring is here from the sound of birds and the smell of flowers. And from the flocks of birds in the sky, and its glittering blue.

Summer. The sun lays waste to it all, as walls and floor turn to a raging fire. I grow drowsy and still. As I shake my head before the spinning ventilator it rises above the walls and the wire fences and I fight to breathe, just as a fish in a tank rises to the surface and, looking desperately at the blue skies, gasps. At night the sound of a soldier whistling intermittently on the watchtower blends with an owl’s hooting. There is a wedding in the neighbouring village. The banging of drums, the women’s ululations and the barking of excited dogs plant a smile on my face just as soon as they steal in through an open window. How sweet to hear life even if we cannot see it!

If only prison did not teach one how beautiful life is. My sons Robin (10) and Robert (5) ask “Daddy, when will you be done here? How long until you come home?” I reply “Not long, not long.” In reality, I do not know when I will be done….

[Follow the links to send appeals on behalf of Liu Xiaobo and Muharrem Erbey.]