Posts Tagged ‘Russia’

PEN Journey 24: Moscow—Face Off/Face Down: Blinis and Bombs—Welcome to the 21st Century

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

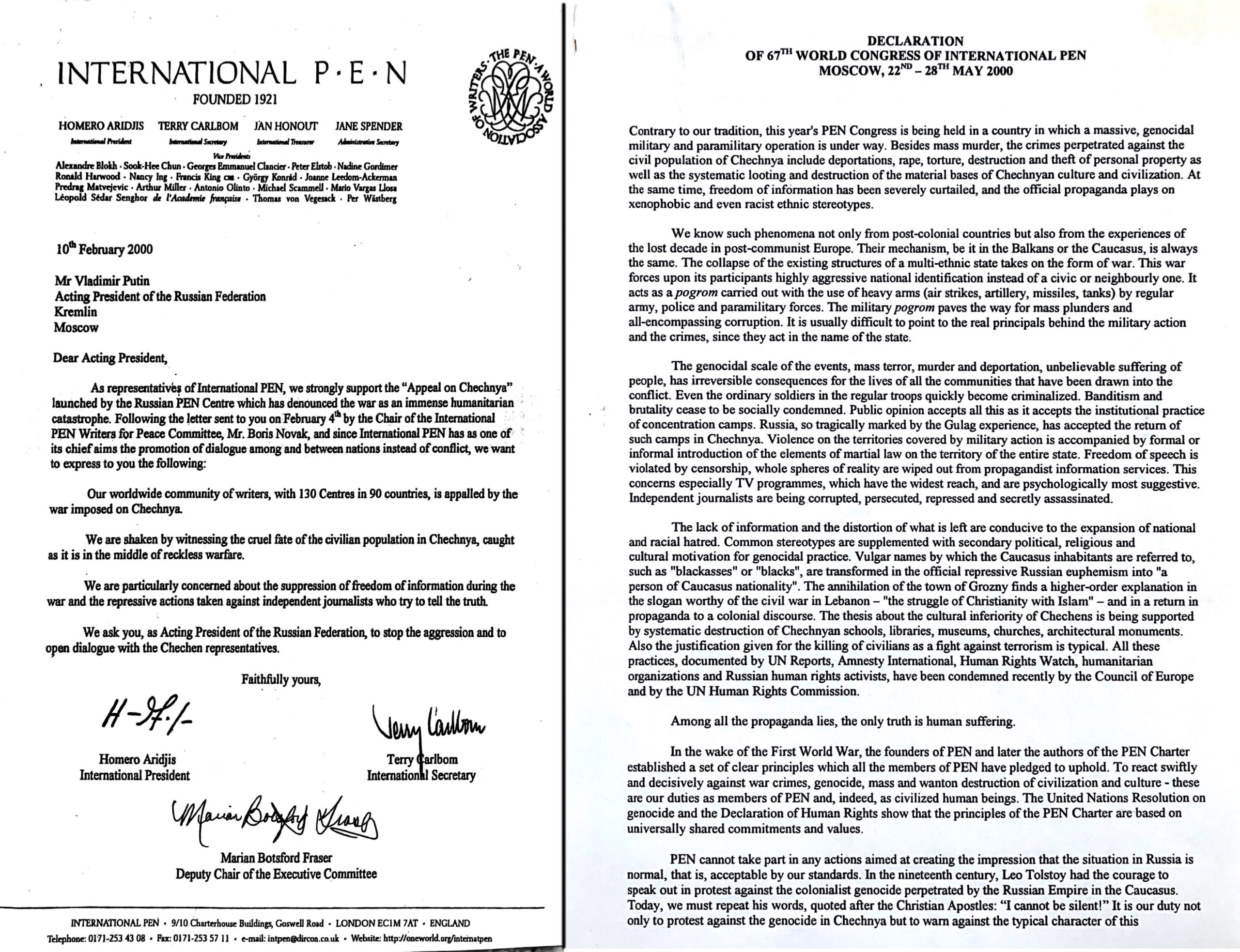

“Contrary to our tradition, this year’s PEN Congress is being held in a country in which a massive, genocidal military and paramilitary operation is under way. Besides mass murder, the crimes perpetrated against the civil population of Chechnya include deportation, rape, torture, destruction and theft of personal property as well as the systematic looting and destruction of the material bases of Chechnyan culture and civilization. At the same time, freedom of information has been severely curtailed, and the official propaganda plays on xenophobic and even racist ethnic stereotypes…” So began a Declaration from the 67th World Congress of International PEN voted by the Assembly of Delegates in May, 2000.

Program for PEN International 67th World Congress, Moscow

The decision to hold the International PEN Congress in Moscow was a controversial one, resulting in some members refusing to attend because of Russia’s prosecution of the war in Chechnya and the concern that holding a Congress in Moscow would give the government an appearance of approval. However, PEN’s Secretariat with the new Executive Committee concluded that the long-planned millennial Congress also presented the opportunity for International PEN to show solidarity with Russian PEN which had been outspoken both on the war and on behalf of Russian journalists and writers under pressure.

“The writers of Russia, united under the auspices of the Russian Centre of the International PEN Club, are concerned about the escalation of the war in Chechnya which is becoming a threat to not only peaceful residents of Grozny-city but also to the national security of Russia. The ultimatum announced to women, children and old people of the Chechen capital makes them hostages of both terrorists and federal forces. It is hard to believe that in this situation the Russian authorities are going to use the same methods as terrorists. We are very aware how hard it is to cut the tight Chechen knot, but in any case innocent people do not have to become victims of the decisions taken…” Russian PEN sent this appeal earlier to the acting President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin.

Russian PEN members, including President Andrei Bitov, had signed the appeal. Russian PEN’s General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko noted at the Congress that it was essential to call on all those involved—Russian and Chechen—to cease their brutalities. Sascha himself had regularly stood up to the Russian government. He championed the cases of imprisoned writers Alexandr Nikitin and Grigory Pasko, both of whom had recently been freed after trials. Pasko, who was a journalist and former Russian Naval officer, had been arrested and accused of espionage for his publication of environmental problems in the Sea of Japan. Nikitin, a Naval officer, had been charged with stealing state secrets by contributing to a report that revealed the sinking of Russian nuclear submarines and the dangers these decaying submarines posed to the environment.

German novelist Günter Grass talk opened PEN’s 67th Congress

The freedom and the openings which many embraced after the break-up of the Soviet Union in the early 1990’s were beginning to close down and restrictions tighten. At the Moscow Congress Pasko expressed his gratitude for everything PEN had done to obtain his freedom. He urged the Assembly to focus on environmental problems. But he warned that the structure of the current Russian government had grown out of the KGB, and he feared nothing good would come for free speech or the environment.

In the opening address of the Congress German novelist Günter Grass, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature the previous year, recounted the many times in the past century that writers had called attention to the abuses and genocides which governments had tried to hide. “At least literature does achieve this—it does not turn a blind eye; it does not forget; it does break the silence,” Grass concluded.

The Congress theme “Freedom of Criticism. Criticism of Freedom…”seemed a particularly UNESCO title, with a focus on how freedom is exercised, noting that freedom unrestrained by morality can lead to a license for corruption, brigandage, state terrorism, censorship and the wanton murder of those who dare to speak out. “That freedom is a double-edged sword is a fact long appreciated in free societies. It is what prompted Voltaire to place a limitation upon it, when it interfered with the freedom of another,” one Congress description noted.

Thus framed, the panels and the work of PEN’s committees proceeded. Many wondered how able PEN members would be to criticize openly as we met both formally and in cafes sharing conversation and meals of blinis and caviar. There was no incident nor interference that I recall at the Moscow Congress nor at the subsequent programs in St. Petersburg, but we were all aware that repercussions could follow after we left. Over time Putin’s government did close down the space for NGO’s with Russian PEN as one of the early targets. (Future blog post.)

The Moscow Congress itself proved an opportunity to celebrate Russian literature and other literature as well as to conduct the work of PEN’s committees which met in halls named after Tolstoy, Pushkin, and Chekov. Many writers from over 70 PEN centers were visiting Moscow for the first time since the Soviet Union broke apart. Since my first trip in 1991 shortly after the coup attempt (PEN Journey 8), the city had changed. Western hotels, restaurants and stores had moved in; certain citizens had amassed wealth; others had lost jobs and security. It was a city of contrasts with children on the street begging, but begging by playing violins. A wealthy new group crowded the lobbies of western hotels and department stores.

On the streets at PEN Congress in Moscow May, 2000: L: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, PEN Vice President; R: Sara Whyatt, PEN Writers in Prison Committee Program Director

In a message to the Congress Andrei Bitov wrote:

Full text of Russian PEN President Andrei Bitov’s message to PEN delegates

I always believed…that I would meet my old age in the USSR under Brezhnev, much though I disliked the idea. I could not allow myself to dream (or I would have been driven to despair) that I would be lucky enough to travel around the world more or less without restriction, that my works would be published without being censored, published with no delay and in their entirety, however hastily written.

Under Brezhnev one could not think of joining the PEN Club—that “reactionary bourgeois, anti-Soviet, etc., organization”! (It turned out only recently that Gorky, Pilniak and Voinovich had all dreamt of such a grouping…)

One could certainly never have imagined its World Congress being held in Moscow!

But fifteen years have elapsed since that time, long enough to see many people grow old and die and another generation come into the world and reach their youth. That is the History none of us, either here or in the wider world, could imagine…

We should not rail at the century that has gone, nor at the passing year—we should hope that they have taught us much. However, judging by events in Russia and in the rest of the world, it is obvious that we have not drawn any sensible conclusions from our experience…

In one tiny drop of the substance of the World Congress is reflected the entire universe, the problems it faces reflect, as in a distorting mirror, world political problems…

We are responsible for each day of our lives, not for the future.

Thank you for having the determination (and courage) to come to Russia at this particular time.

PEN’s business at the Assembly of Delegates included the International Secretary Terry Carlbom’s report on PEN’s relationship with UNESCO as the only global organization representing literature associated with UNESCO and a preliminary notice about a multi-year strategic plan under development. Business also included the election of the International President. Homero Aridjis was standing for a second term, and former International Secretary Alexander Blokh of Russian origin had returned to this PEN Congress for the first time since he’d stepped down as International Secretary in 1998, (PEN Journey 20) and he was also running for President. I was asked to chair the Assembly for the election, including during a stir that arose when Alex wasn’t present to speak for his candidature. He’d left the meeting early for an appointment, mistakenly thinking he would speak in the afternoon. However, there was no afternoon session, and controversy arose over whether the election should be postponed so he could speak. I ruled that he would be the first item on the morning agenda and then the election would proceed as scheduled. Homero Aridjis won a second term; Alexander Blokh continued to serve PEN for many years as a Vice President and President of French PEN.

Also at the Congress Martha Cerda (Guadalajara Center) succeeded Lucina Kathmann as Chair of the Women Writers’ Committee; Veno Taufer (Slovene PEN) succeeded Boris Novak, who’d opposed holding the Congress in Moscow and had stepped down as chair of the Writers for Peace Committee, and Eugene Schoulgin (Swedish PEN) was confirmed as the new Writers in Prison Committee Chair.

In his farewell comments as WiPC chair Moris Farhi quoted Günter Grass’s address that literature always breaks the silence. Moris added that by breaking the silence, by telling the truth and exposing wrong-doing, literature also defied fear and embraced courage. The members of International PEN had witnessed this defiance of fear and the manifestation of courage time and again. Moris noted among those with courage were Grigory Pasko, Alexander Tkachenko and our colleague Boris Novak.

The Moscow Congress saw the return of delegates from Chinese PEN after a decade-long absence post Tiananmen Square. Two resolutions on China were presented, one calling for the release of dissident writers imprisoned in China and another protesting the long prison terms for writers in Tibet. The Chinese delegate objected to both resolutions, arguing first that Tibet shouldn’t be singled out as though it were not part of China. He also said that the Chinese people and Chinese writers cared for human rights after centuries of feudal society, but the West emphasized individual rights and values while the Chinese valued collective human rights and obligations to the family and society. The Chinese believed that human rights in a given country were related to the social system, the level of economic development and historical and cultural traditions of that country, and they encompassed the right to development and subsistence. A country of more than 1.2 billion people had to find food and clothing. It was impossible for one pattern to solve all existing problems. The Cold War had ended, but its influence remained with those who believed their values, their concept of human rights, their position were the only correct ones in the world. Dialogue was the only way to resolve the differences of view, a dialogue based on equality and mutual respect.

Hands shot up seeking to respond. At least 25 delegates at the Assembly spoke, welcoming the return of the Chinese delegates to the PEN Congress, but most taking exception to the argument of the relativity of human rights in PEN’s work. The first to speak was Eric Lax of PEN Center USA West who said he appreciated the speaker’s comments but wanted to add that the PEN Charter, to which all members subscribed, was very clear that freedom to write was a basic tenant of the organization and that information should pass unimpeded without restriction. Some questioned the way the resolution was written. Alexander Tkachenko of Russian PEN said he felt PEN should be understanding of people living under a regime about which the rest of PEN knew little. It was up to the Assembly to decide whether to support the resolution; they needn’t accept the Chinese delegate’s opinion, but they should respect it. He didn’t want the Chinese to be missing from PEN for another ten years. PEN should be tolerant of those for whom it was extremely dangerous to discuss such questions. The Assembly applauded. A small amendment was made to the resolutions, both of which passed with large majorities, though not unanimously.

The following year the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) came into being, a center of independent writers and democracy activists inside and outside of China. One of the founding members and the second president of ICPC (2003-2007) was writer Liu Xiaobo, on whose behalf PEN worked twice when he was imprisoned after Tiananmen Square and again when he was arrested in 2009. Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010, but he was incarcerated in a Chinese jail, and he died in custody in 2017.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 25: War and more War: Retreat to London

Reclaiming Truth In Times Of Propaganda

PEN International’s 83rd Congress in Lviv, Ukraine took on truth and words, history and memory, women’s access and equality, cyber trolling, fake news and threats to freedom of expression worldwide, including public panels focused on the three super powers: “America’s Reckoning—Threats to the First Amendment in Trump’s America,” “China’s Shame—How a Poet Exposed the Soul of the Party,” and “Putin’s Power Play—The Decline of Freedom of Expression in Russia.”

At its annual gathering PEN hosted more than 200 writers, editors, staff and visitors from 69 PEN centers around the world in the historic city of Lviv, the Cultural Capital of Ukraine and a UNESCO World City of Literature. Straddling the center of Europe, on the fault lines between East and West, Lviv changed its name and governing domain eight times between 1914 and 1944, passing from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to Russia, back to Austria, Ukraine, Poland, Soviet Union, Germany then back to the Soviet Union and now finally in the Ukraine.

The path of European history cuts through the city and can be seen in architecture, culture and conversation. Though writers celebrated literature in the western Lviv, fighting was still underway in eastern Ukraine and the Crimea. PEN’s Russian center didn’t attend the Congress at the same time a new PEN St. Petersburg center was elected. Other new centers joining PEN’s network included Cuba, the Gambia and South India.

In times of war, the first casualty is truth, noted PEN’s report “Freedom of Expression in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine: External Aggressions, Internal Challenges.” The report and the Congress addressed the aggressive role of propaganda in conflict. In Ukraine, in Russia and worldwide there has been a proliferation of false narratives.

PEN’s report on Ukraine noted: “Despite significant improvements, democracy in Ukraine remains ‘a work in progress’ and, among other things, severe challenges to the enjoyment of the right to free expression remain. These include the use of the media to foster political interests and agendas, delays in reforming state-owned media; and intimidation and attacks on journalists followed by impunity for the perpetrators. On the other hand, public criticism is growing, albeit slowly, including demands for more transparent and unbiased journalism.”

In Russia authorities are taking increasingly extreme legal and policy measures against freedom of expression, according to a PEN/Free Word Association report “Russia’s Strident Stifling of Free Speech.”

No writers are in prison in Ukraine, but in the Crimea, which Russia annexed in 2014, filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, an opponent of annexation, was arrested and is now serving a 20-year sentence inside a Russian prison on terrorism charges he denies. At PEN’s Assembly, delegates remembered Pavel Sheremet with an Empty Chair. A Belarusian-born Russian journalist and free speech advocate, Sheremet wrote for an independent news website and hosted a radio show where he reported and commented on political developments in Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. He died in a car bomb explosion in Kiev July, 2016. Shortly before he was assassinated, he’d written about corruption among law enforcement in Belarus, Ukraine and propagandists in Russia. His murder remains unsolved.

Resolutions at the Congress also addressed writers imprisoned in Turkey, China, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, and Eritrea and killings in Mexico, Russia, Venezuela, Bangladesh and India. Concerns about increasing censorship in Hungary, Poland, India, Turkey, and Spain were acted on as was the restriction of linguistic rights for Kurdish writers in Turkey, Hungarians in Ukraine and Uyghurs in China.

Expressing concern about the abuse of Interpol’s Red Notice system by some member states “in order to repress freedom of expression or to persecute members of political opposition beyond their borders”, PEN called on the Council of Europe “to refrain from carrying out arrests…when they have serious concerns that the notice in question could be abusive.”

PEN expanded Article 3 of its Charter for the first time since the document’s inception over 90 years ago. The Assembly voted new language which would include a wider mandate, reaching beyond just opposing hatreds of race, class and nations to include by extension gender, religion and other categories of identity. Article 3 of PEN’s Charter, which can be linked to here, now reads: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

PEN also passed a Women’s Manifesto noting “the use of culture, religion and tradition as the defense for keeping women silent as well as the way in which violence against women is a form of censorship needs to be both acknowledged and addressed.”

At the Opening Ceremony author of East West Street Philippe Sands, whose grandfather was born in Lviv, narrated the origins of international human rights law and the concepts “crimes against humanity” and “genocide.” These legal frameworks were developed by two lawyers who passed through the very university where the delegates sat. The legal teams prosecuting at the Nuremberg trials after World War II used these frameworks to secure convictions, including the conviction of Hans Frank, Hitler’s lawyer who governed the area around Lviv and sent over 100,000 Jews to concentration camps and death.

“The Foundations of human rights law came from here,” Sands said. “Every individual has rights under international law.” The lawyers Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin studied at the university at different times and never met. One escaped to Austria then England, the other to America. Lauterpacht protected the rights of the individual with the concept he developed of “crimes against humanity” and Lemkin protected the group with the legal construct for “genocide.” Both men were on the legal teams that successfully secured convictions at Nuremberg.

“No organization in the world knows better than PEN the need to protect individuals and to protect others,” Sands concluded.

Jennifer Clement, PEN International President

Andrei Kurkov from Ukranian PEN and Carles Torner, Executive Director PEN International

At the closing ceremony author David Patrikarakos focused on the current situation as the 21st century unfolds and addressed “Fact, Fiction and Politics in a Post Truth Age.” He told the story of Vitali, who became a troll for the Russian state working at a Troll farm. “When Vitali went to the Troll farm, he had enlisted in the Russian Army; he just didn’t wear a uniform. He and others became their own army with a virtual information war, and it is effective,” said Patrikarakos.

As an unemployed journalist, Vitali developed propaganda, rewriting reports, doctoring news accounts to enhance Russia’s position then distributed these on social media, along with fake news, fake pictures and memes to a wide audience, all relating to Russia’s assault on the Crimea. According to Patrikarakos (Nuclear Iran: The Birth of an Atomic State), who has also written for the New York Times, Financial Times, Guardian, and Wall Street Journal, the Russian state spent $250 million to sow discord in its battle for Crimea.

In the Troll farm where Vitali and other journalists worked, the first floor focused on distorting news reports and circulating them. On the second floor people worked through social media, posting memes and making up ads; on the third floor bloggers wrote about how life was better in Russian and bad for Russians in the Ukraine and on the fourth floor, people posted comments on other sites.

According to Patrikarakos and his sources, there was a bag of sim cards to request new accounts, and people were encouraged to make the accounts in the names of females because women were more likely to be believed. “The first goal was to shore up and get true believers, to give a narrative and sow as much confusion on reality as possible,” Patrikarakos said.

After three months Vitali told his boss he wanted to quit. He wrote an expose of the Troll farm. When it came out, he received threats such as “Don’t you know you can get punched in the face.”

“As I went through towns of Eastern Ukraine, content had seeped into walls,” said Patrikarakos. “In Eastern Ukraine, Putin’s nervous system is on display. There is belief in fake news—that Ukrainians want to kill Russian speakers. Social media is supposed to connect us but it has also shattered unity and divided people; it sets people at loggerheads. The news that young people get depends on who they follow. We all follow who we like, and so prejudice is reaffirmed. Facts are less important than narratives. The new word in 2016 from the Oxford dictionary was ‘post-truth’ which is finding linguistic footing. The goal of many is not to trust truth but to subvert truth,” he concluded.

What can we do to counter this trend? Patrikarakos advised:

- Go out of your way to see people who don’t think like you.

- Go directly to the source of information and go to the news.

- Read those you don’t agree with.

- Read books. (Patrikarakos’ new book is More Than 140 Characters)

- Mistrust the mob.

- Beware of Click bait.

- Click off.

Parallel Universe in a Glassed Concert Hall in Iceland

If you want to understand politics—it’s like being in a book club where everyone discusses the grammar.

So said actor/comedian Jon Gnarr, Mayor of Reykjavik, Iceland when he addressed the recent 79th PEN International Congress. Gnarr was elected Mayor in 2010 from the Best Party, which he and friends with no background in politics created as a satirical party after the economic meltdown in Iceland a few years ago. They won over a third of the seats on the City Council with a platform that included free towels in all swimming pools, a polar bear for the zoo and “all kinds of things for weaklings.” After he was elected, Gnarr declared he wouldn’t form a coalition government with anyone who hadn’t watched the TV series The Wire.

The politician with a short black tie, a sense of humor and a view of politics as a parallel universe resonated with the audience of over 200 writers at the Opening Ceremonies of the PEN Congress. Writers from 70 centers of PEN gathered to deliberate and debate literature and the situation for writers and freedom of expression around the world, a world they agreed often bordered on the absurd, but the absurd with serious consequences.

The Assembly discussed and passed resolutions on the challenges to freedom of expression in countries including Mexico, China, Cuba, Vietnam, North Korea, Eritrea, Belarus, Syria, Egypt, Turkey, Tibet, and Russia. The delegates walked en masse to the Russian Embassy to present their resolution protesting the recent legislation on blasphemy and “gay propaganda.” And they applauded the announcement during the Congress of the release of Chinese poet Shi Tao 15 months before the end of his 10-year sentence.

“Shi Tao has been one of our main cases since his arrest in 2004, an honorary member of a dozen PEN centers and one of the first and most significant digital media cases,” said Marian Botsford Fraser, Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. “Shi Tao’s arrest and imprisonment, because of the actions of Yahoo China, signaled a decade ago the challenges to freedom of expression of internet surveillance and privacy that we are now dealing with.”

The delegates challenged the secret surveillance of citizens recently uncovered in the United States and the United Kingdom and the prosecution of those who revealed programs violating international human rights norms.

“As an organization dedicated to preserving free expression and creative freedom, PEN is particularly troubled by recent revelations concerning the nature and scope of electronic surveillance programmes in use by the United States’ National Security Agency and parallel programmes such as those being carried out by the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in the United Kingdom. As leaks about the U.S. government’s PRISM programme, the U.K. governments Tempora programme, and other such programmes make clear, certain governments now possess the capacity to monitor the private telephone, internet and other digital communications of every citizen on earth—among them, the communications of PEN’s 20,000 members worldwide.”

In this parallel universe one of the new centers PEN elected at the Congress was the PEN Center of Myanmar. PEN Myanmar will be an early citizens’ organization there defending writers and civil society in a country that just a few years ago was one of the most closed societies on earth. Also sitting in the glassed waterfront Concert Hall among the Assembly of Delegates were North Korean writers who now meet as an exile center of PEN, but as voices stir and comedians and actors and politicians mingle, who knows the universe that may yet emerge?